Abstract

It is important to examine and comprehend how HIV interacts with the immune system in order to manage the infection, enhance patient outcomes, advance medical research, and support global health and socioeconomic stability. In this study, we formulate the dynamics of HIV infection to investigate the intricate interactions between HIV and \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells. The Atangana-Baleanu and Caputo-Fabrizio derivative frameworks are applied to comprehensively examine the phenomenon of HIV viral transmission. The basic concepts and results of fractional calculus are presented for the analysis of the model. In our work, we focus on the dynamical behavior of HIV and immune system. We introduce numerical schemes to elucidate the solution pathways of the recommended system of HIV. We have shown the influence of various input factors on the solution pathways of the recommended fractional system and highlighted the oscillatory behavior and chaotic nature of the dynamics. Our findings demonstrate the complexity of the system under study by revealing the existence of the chaotic and oscillatory nature in the dynamics of HIV. In order to quantitatively characterize HIV dynamics, a number of simulations are carried out, providing a visual representation of the effects of different input variables. It has been observed that the chaos and the oscillatory behaviour is strongly related to the nonlinearity of the system. The present study provides a basis for further initiatives that try to enhance interventions and policies to lessen the worldwide burden of infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to reports, HIV infections impair the immune system of their human hosts and harm internal organs including the heart, brain and kidneys, which finally causes death. Although yet no treatment is designed for this infectious disease, but there are other effective retroviral treatments that can greatly improve the health of patients. However, the excessive use of these medications can lead to adverse side effects. On the report of studies, HIV infection is the most hazardous virus in the world, having an impact on a variety of industries. In 2017, 1.8 million people were living with HIV, and 940,000 of them passed away. Presently, a greater number of individuals are engaging in therapy compared to previous times. Some individuals have manifested symptoms resembling headaches, rashes, sore throats, influenza, and fevers on certain occasions. In some cases the symptoms including weight gain, coughing, fever, enlarged lymph nodes and diarrhoea are dangerous. The significance of treatment is paramount, given its critical role in enhancing individual health outcomes, mitigating disease progression and transmission, and improving quality of life1,2,3. Additionally, treatment supports public health initiatives and fosters economic and medical advancements4,5. Although various treatments have been developed, there is still a need for more effective therapies to manage this infectious disease.

Mathematical modeling of HIV and the immune system continues to be an important tool in understanding the disease and improving treatment outcomes. These models provide enough details and key factors of the transmission route of diseases. The authors in6 proposed the use of compartment models as a viable way to combat HIV infection in humans. The immune deficiency virus’s dynamics during the whole infection process were examined by Duffin et al.7. The influence of HIV testing, treatment, and control on HIV transmission in Kenya was mathematically modeled by the researchers8. In9, the researchers modelled the transmission of HIV with treatment and pathogenics to investigate the intricate phenomena of the infection. In 1999, some researchers constructed an HIV model and statistically identified the most beneficial control measures10. Multiple models were subsequently developed by the authors in11,12,13 to explore the dynamics of HIV infection, incorporating important elements such as intracellular delays and viral mutation. The study in14 examined two transmission methods: direct cell-to-cell transfer and infection by free virions. In15, a model with four distinct classes of \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cell populations infected by HIV was employed to analyze their interrelationships. In16, Perelson and Nelson employed a dynamical model and a parameter estimation approach to identify key aspects of HIV-1 infection dynamics. The model initially proposed by Perelson and Nelson was subsequently examined by Raun and Callshaw17, who categorized it into three compartments: free virus, healthy \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells, and infected \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells. Further, the existence theory of an HIV-1 infection model was explored in18 to enhance the understanding and analysis of HIV-1 dynamics. Furthermore, a multistage Homotopy Perturbation Method (HPM) was introduced for path tracking of damped oscillations in a model of HIV infection in CD4+ T cells19. In20, computational solutions were presented for the fractional mathematical model of HIV-1 infection in \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells, which causes AIDS, taking into account the impact of antiviral drug therapy. The main objective of this work is to elucidate the impact of input factors on the system’s dynamics to identify the most sensitive parameter for controlling the infection.

It is eminent that different mathematical frameworks have been employed in the literature to represent the dynamics of biological processes21,22,23. In the realm of disease modeling, fractional calculus offers significant advantages over classical approaches24,25. Fractional derivatives offer a powerful and versatile mathematical tool for modeling and understanding the intricate behaviors observed in biological systems26,27. Their ability to capture memory effects, non-local interactions, and complex structures makes them invaluable for advancing our knowledge and developing practical applications in biology and medicine. By embracing fractional calculus, researchers can achieve more accurate and comprehensive models, leading to better predictions and innovations in the biological sciences28,29. Although fractional calculus includes numerous operators, we chose to analyze our model using the Atangana-Baleanu and Caputo-Fabrizio operators. These fractional operators effectively captures real-world processes characterized by non-local and non-singular properties. Therefore, we choose to model the dynamics of HIV infection with nonlocal and nonsingular kernels to achieve more accurate and precise results.

The rest of the work is organized as follows: In section "Formulation of HIV model", we structure the dynamics of HIV and \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\)" T cells with non-integer derivatives involving nonsingular and nonlocal kernel. The basic concepts and main results of the fractional calculus is presented in Sect. "Results and concepts of fractional theory for the analysis of the model. In section "Solution of the HIV system", a numerical schemes are introduced to visualize the dynamical behavior of the recommended system of HIV. Through numerical simulations, we visualized the chaotic natural and the solution pathways in section "Results and discussion" of the this research work. We have shown the impact of different input factors on the output of the system. The limitations of this work have been acknowledged and potential future directions are outlined in section " Limitations of the work". In section " Conclusion", we presented the conclusion remarks.

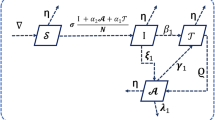

Formulation of HIV model

We organised the HIV transmission phenomena to show the interlink of infected T-cells \(\mathcal {I}\), healthy T-cells \(\mathcal {T}\) and HIV-free virus \(\mathcal {V}\). A number of researchers have developed and tested the dynamics of HIV in the past to explain the intricate dynamics of HIV30,31,32. The authors in19 developed the following model for the dynamics of HIV:

where \(\rho\) is the rate at which the body recruits new T-cells, \(\beta _{T}\) is the death rate of T-cells while \(\beta _{V}\) and \(\beta _{I}\) are the rates at which HIV and infected T-cells dies, respectively. The parameter \(\nu\) signifies the infection rate affecting healthy T-cells, while \(\mu\) denotes the reproduction number associated with cells as a consequence of infected T-cells. The rate associated with the growth of healthy T-cells is indicated by \(\eta\). The model presented in33 is given below

in which the saturation incidence rate would allow HIV and infected T-cells to infect healthy \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells. The model of HIV infection with variable recruitment for the healthy T-cells illustrated in34 is presented as:

where \(\delta\) is the effectiveness of a protease inhibitor while \(\nu\) is the rate of cellular infection. Numerous fresh definitions of non-integer derivatives have been put out recently and utilised to create mathematical models for a wide range of real-world systems that involve memory, history, or nonlocal effects. We illustrate the above recommended model of HIV infection through CF derivative as

where \(\upsilon\) is order of CF derivative. Since it is commonly known that the definite integral lacks a regular kernel, many definitions have included both kinds of kernels. The ABC derivative, which was first presented by the researcher in 2016, is one of the significant concepts that has lately received attention. The dynamics of HIV in the framework of ABC derivative is given by

where \(^{ABC}_0 D^{\upsilon }_t\) indicate Atangana-Baleanu derivative. These operators are more attractive for the researchers and scientists due to nonlocal and nonsingular kernel. In the following section of the work, we introduce some concepts and results of CF and ABC fractional operators.

Results and concepts of fractional theory

Here, we list the essential notions of fractional theory for the examination of recommended system. Below are some of the key findings and theories of CF and ABC:

Definition 1

Assume that \(q \in \mathfrak {H}^1(a_{1}, a_{2})\), where \(a_{2} > a_{1}\), then the CF derivative35 of order \(\upsilon\) can be stated as

where \(\upsilon \in [0, 1]\) and \(\mathcal {W}(\varkappa )\) represent normality with \(\mathcal {W}(0) = \mathcal {W}(1) = 1\)35. If \(q \notin \mathfrak {H}^1(a_{1}, a_{2})\), then we obtain

Remark 1

Suppose that \(\varphi =\frac{1-\upsilon }{\upsilon }\in [0, \infty )\) and \(\upsilon =\frac{1}{1+\varphi }\in [0, 1]\), then Eq. (7) can also be stated as

Moreover,

The definition of fractional integral is given as follows:

Definition 2

Let us assume any function q then the fractional integral can be defined as

where \(\upsilon\) indicate the order of fractional integral and \(0<\upsilon <1\).

Remark 2

Further modified form of Definition 2 is given as

which gives \(\mathcal {W}(\upsilon )=\frac{2}{2-\upsilon }\), \(0<\upsilon <1\). Utilizing Eq. (11), Nieto and Losada obtained Caputo derivative of order \(\upsilon\), which is stated as

Definition 3

Consider a function g such that \(g\in \mathfrak {H}^1(b_{1},b_{2})\), \(b_{2}>b_{1}\), and \(z \in [0,1],\) then ABC represent the AB fractional operator in Liouville-Caputo structure defined as

Definition 4

\(^{{ABC}}_{b_{1}}I^{z}_{t}g(t)\) represent the integral of AB derivative stated as follows

Obviously, we get the initial function as the fractional-order z tends to 0.

Theorem 1

Suppose a continuous function g such that \(g \in C[b_{1},b_{2}]\), then the the resulting outcome satisfies the condition36

Furthermore, the Lipschitz condition holds for the newly developed ABC derivative as

Theorem 2

The equation for the fractional differential system is given as36

which yields a unique solution as

Solution of the HIV system

Here, our primary objective is to illustrate numerical method to demonstrate the solution pathways of the recommended system. These numerical schemes will be utilized to visualize the dynamics of the system and to illustrate the chaotic phenomena of the system.

Solution through Caputo-Fabrizio

The solution analysis of a fractional system plays a pivotal role in enhancing our understanding of system behavior, validating models, making predictions, optimizing performance, and informing decision-making across diverse fields of study. There are many numerical methods available, but we will use the method developed in37 to analyze our recommended fractional system (4) for HIV infection. We start by looking at the first equation of our system:

Let \(t=t_{\ell +1}, \ell =0,1, \dots ,\) so we obtain

and

The successive terms difference is stated below

Now we approximate the function \(\textrm{V}_1 (t, \mathcal {J}_1)\) in the time interval \([t_\kappa ,t_{\kappa +1}]\) by utilizing interpolation polynomial and obtain

where q represent the time spent and \(q=t_\ell -t_{\ell -1}\). The above stated \(\mathcal {P}_\kappa (t)\) is utilized to obtain

Here, putting Eq. (29) in Eq. (16), yield the following result

which is required solution for the first equation of the system. In the same way, we can determine for the second and third equation of (4) given by

and

The two-step Adams-Bashforth approach (ABA) used in this method for the CF takes into consideration the nonlinearity of the kernel as well as the exponential decay rule for the CF.

Solution through Atangana-Baleanu

Here, we will represent the solution pathways of our system (5) of HIV infection. We initially adopt the following fractional system to develop the necessary numerical method for our fractional model as follows:

using the theory of fractional calculus, we attain

Take \(t=t_\zeta\), then we obtain

and for \(t_{\zeta +1}\), we get

We get the difference for above equation as

where

Using approximation we obtain

where \(q=t_\ell -t_{\ell -1}\). Then, we get the following

Similarly, we obtain

so, we get the following result

The above yields that

The method described above is for the ABC fractional derivative. Here, we run different simulations to see how different factors affect the relationship between HIV and T-cells. The settings we use for the parameters in this section are meant to highlight the chaotic and up-and-down behavior of the system (5) through simulations.

Results and discussion

The choice between CF and AB kernels depends on the specific requirements of the model and the nature of the system being studied. The effectiveness of CF fractional derivatives is evident in their ability to provide accurate, stable, and computationally efficient modeling of systems with memory effects. Their non-singular nature, exponential decay properties, and simplicity make them a powerful tool in various scientific and engineering fields. On the other hand, the AB kernel, with its complex memory effects via the Mittag-Leffler function, is better suited for systems requiring a more nuanced representation of memory and hereditary properties. By using both kernels, researchers can leverage the strengths of each to develop more robust and accurate models.

Despite extensive international efforts to mitigate HIV/AIDS, the disease continues to exert a substantial burden on affected families. Elevated healthcare expenses, diminished employment income, and the depletion of resources exacerbate the income-to-expenditure gap, underscoring the persistent challenges. Consequently, an examination of the fundamental causes of HIV infection is imperative to mitigate these adverse consequences. The primary objective of this research phase is to elucidate the chaotic behavior and time series dynamics of the system, aiming to enhance comprehension of the diverse factors influencing it. Employing various numerical scenarios, we explore how input elements contribute to the dynamics of HIV. For numerical purposes, parameter values are derived from Table 1, and initial conditions for state variables are assumed as \(\mathcal {T}(0)=300, \mathcal {I}(0)=200\), and \(\mathcal {V}(0)=120\).

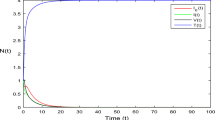

In Figs. 1, 2, 3, we visually depict the oscillatory behavior inherent in the system. Notably, the solution pathways of the system exhibit a significant dependence on the fractional parameter. The findings of these simulations indicate that the order of the fractional derivative positively influences HIV dynamics, suggesting its potential utility as a preventive measure. The chaotic nature of the system is demonstrated in Figs. 4, 5, 6, where diverse values of input factors lead to varied system outputs. The interplay between the oscillatory and chaotic aspects is intricately linked by the non-linearity of the model, inducing unstable states within the system. Policymakers are urged to consider the input parameter, as it has been empirically shown to exert a remarkable impact on the system’s output. This insight underscores the importance of incorporating fractional parameters in policy decisions related to HIV dynamics.

Chaos theory delves into nonlinear phenomena characterized by inherent unpredictability and difficulty in control. This field focuses on the deterministic principles and fundamental patterns of dynamical systems, particularly sensitive to initial values of state variables, challenging the prior belief of their wholly unpredictable chaotic states. The significance of these conditions lies in the valuable insights they offer into the HIV infection system. The chaotic behavior observed in the system illustrates the profound impact of minor perturbations, leading to substantial changes. The instability of the system is vividly portrayed in these chaotic plots, underscoring its susceptibility to initial conditions and inherent uncertainty. Our research underscores that the nonlinearity of the system significantly amplifies chaos and oscillation, rendering the system inherently unstable. This revelation contributes to a deeper understanding of the intricate dynamics of the HIV infection system and emphasizes the importance of considering nonlinear factors in system analysis and intervention strategies.

Limitations of the work

The importance of this research lies in its potential to deepen the understanding of HIV dynamics, particularly the interaction between HIV and CD\(4^+\) T-cells. By utilizing fractional derivatives and exploring the chaotic and oscillatory behaviors within the system, this research addresses a critical gap in current HIV studies. The identification of chaotic behavior and the influence of fractional-order dynamics on disease progression provide new insights that could lead to more effective treatment strategies. This work not only contributes to the scientific community’s knowledge of HIV but also has practical implications for developing interventions that could enhance patient outcomes and inform global health policies.

Future work

-

Despite the promising insights provided by this study, a notable limitation is the lack of validation using clinical data or published datasets to substantiate the application of the Atangana-Baleanu and Caputo-Fabrizio derivatives. Future research should address this limitation by incorporating clinical data or relevant published datasets for model validation. Such validation would enhance the reliability of the models and ensure that the theoretical predictions align with real-world HIV infection dynamics, thereby strengthening the overall impact and applicability of the research.

-

Future research could focus on enhancing the model by integrating a broader spectrum of biological and environmental factors, such as the impact of antiretroviral therapy and the influence of co-infections. Additionally, expanding the model to account for individual variability in immune responses and viral characteristics would increase its relevance and applicability to a wider range of patients.

Conclusion

HIV infection weakens the body’s immune defenses by attacking the immune system and destroying T-cells, presenting a major challenge to global public health. Although recent data suggest a decline in HIV infections, thorough research is essential to fully understand the complex interactions between viruses and T-cells. To tackle this issue, we have meticulously analyzed the intricate relationship between \({\text{CD}}4^{ + }\) T-cells and HIV using non-integer derivatives. We considered the relation between infected T-cells, uninfected T-cells and HIV viruses in our system. The recommended HIV model is demonstrated through CF and ABC fractional derivatives. We investigated the solution pathways and chaotic dynamics of the proposed system using numerical methods. Various simulations were conducted to examine the critical conditions of the system. Our findings confirm the presence of chaotic behavior within the model. We observed that fractional-order dynamics influence the solution pathways of the HIV infection system. The impact of different input factors has been shown on tracking path behavior of the system. We identified a significant correlation between chaotic and oscillatory behaviors. Further work will focus on assessing the impact of medical advancements on the progression of the virus and developing more effective treatment strategies. We aim to extend the current model to analyze the effects of treatment and vaccination on HIV infection.

Data availibility

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the correspondingauthor on reasonable request.

Change history

12 November 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79313-2

References

Grigore, N. I. C. O. L. A. E. et al. The evaluation of biochemical and microbiological parameters in the diagnosis of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Rev. Chim 68, 1285–1288 (2017).

Boicean, A. et al. Therapeutic perspectives for microbiota transplantation in digestive diseases and neoplasia: A literature review. Pathogens 12(6), 766 (2023).

Grigore, N. et al. A risk assessment of clostridium difficile infection after antibiotherapy for urinary tract infections in the urology department for hospitalized patients. Rev. Chim. 68, 1453–1456 (2017).

Guignard, M. I. et al. Functionalization of a bamboo knitted fabric using air plasma treatment for the improvement of microcapsules embedding. J. Text. Inst. 106(2), 119–132 (2015).

Nasution, F. M. et al. HIV/AIDS in Indonesia: Current treatment landscape, future therapeutic horizons, and herbal approaches. Front. Public Health 12, 1298297 (2024).

Ogunlaran, O. M. & Oukouomi Noutchie, S. C. Mathematical model for an effective management of HIV infection. BioMed Res. Int. 2016(1), 4217548 (2016).

Duffin, R. P. & Tullis, R. H. Mathematical models of the complete course of HIV infection and AIDS. J. Theor. Med. 4(4), 215–221 (2002).

Omondi, E. O., Mbogo, R. W. & Luboobi, L. S. Mathematical modelling of the impact of testing, treatment and control of HIV transmission in Kenya. Cogent Math. Stat. 5(1), 1475590 (2018).

Wodarz, D. & Nowak, M. A. Mathematical models of HIV pathogenesis and treatment. BioEssays 24(12), 1178–1187 (2002).

Nowak, M. & May, R. M. Virus dynamics: Mathematical principles of immunology and virology: Mathematical principles of immunology and virology (Oxford University Press, UK, 2000).

Chen, S. S., Cheng, C. Y. & Takeuchi, Y. Stability analysis in delayed within-host viral dynamics with both viral and cellular infections. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 442(2), 642–672 (2016).

Elaiw, A. M. & Almuallem, N. A. Global dynamics of delay-distributed HIV infection models with differential drug efficacy in cocirculating target cells. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 39(1), 4–31 (2016).

Elaiw, A. M. & Raezah, A. A. Stability of general virus dynamics models with both cellular and viral infections and delays. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 40(16), 5863–5880 (2017).

Pourbashash, H., Pilyugin, S. S., De Leenheer, P. & McCluskey, C. Global analysis of within host virus models with cell-to-cell viral transmission. Discret. Contin. Dyn. Syst. B 19(10), 3341 (2014).

Perelson, A. S., Kirschner, D. E. & De Boer, R. Dynamics of HIV infection of CD4+ T cells. Math. Biosci. 114(1), 81–125 (1993).

Perelson, A. S. & Nelson, P. W. Mathematical analysis of HIV-1 dynamics in vivo. SIAM Rev. 41(1), 3–44 (1999).

Culshaw, R. V. & Ruan, S. A delay-differential equation model of HIV infection of CD4+ T-cells. Math. Biosci. 165(1), 27–39 (2000).

Bushnaq, S. A. M. I. A., Khan, S. A., Shah, K. & Zaman, G. Existence theory of HIV-1 infection model by using arbitrary order derivative of without singular kernel type. J. Math. Anal. 9(1), 16–28 (2018).

Vazquez-Leal, H. et al. Multistage HPM applied to path tracking damped oscillations of a model for HIV infection of CD4+ T cells. Br. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 4(8), 1035–1047 (2014).

Abdel-Aty, A. H., Khater, M. M., Dutta, H., Bouslimi, J. & Omri, M. Computational solutions of the HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T-cells fractional mathematical model that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) with the effect of antiviral drug therapy. Chaos Solitons Fractals 139, 110092 (2020).

Din, A., Li, Y. & Yusuf, A. Delayed hepatitis B epidemic model with stochastic analysis. Chaos Solitons Fractals 146, 110839 (2021).

Shah, S. M. A., Tahir, H., Khan, A. & Arshad, A. Stochastic model on the transmission of worms in wireless sensor network. J. Math. Tech. Model. 1(1), 75–88 (2024).

Ain, Q. T. Nonlinear stochastic cholera epidemic model under the influence of noise. J. Math. Tech. Model. 1(1), 52–74 (2024).

Khan, W. A., Zarin, R., Zeb, A., Khan, Y. & Khan, A. Navigating food allergy dynamics via a novel fractional mathematical model for antacid-induced allergies. J. Math. Tech. Model. 1(1), 25–51 (2024).

Khan, F. M. & Khan, Z. U. Numerical analysis of fractional order drinking mathematical model. J. Math. Tech. Model. 1(1), 11–24 (2024).

Jan, R. et al. Fractional view analysis of the impact of vaccination on the dynamics of a viral infection. Alex. Eng. J. 102, 36–48 (2024).

Alharbi, R., Jan, R., Alyobi, S., Altayeb, Y. & Khan, Z. Mathematical modeling and stability analysis of the dynamics of monkeypox via fractional-calculus. Fractals 30(10), 2240266 (2022).

Jan, A., Jan, R., Khan, H., Zobaer, M.S. and Shah, R. Fractional-order dynamics of Rift Valley fever in ruminant host with vaccination. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. (2020).

Jan, R., Boulaaras, S., Alyobi, S. & Jawad, M. Transmission dynamics of Hand-Foot-Mouth Disease with partial immunity through non-integer derivative. Int. J. Biomath. 16(06), 2250115 (2023).

Zhou, X., Song, X. & Shi, X. A differential equation model of HIV infection of CD4+ T-cells with cure rate. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 342(2), 1342–1355 (2008).

Mobisa, B., Lawi, G.O. & Nthiiri, J.K. Modelling in vivo HIV dynamics under combined antiretroviral treatment. J. Appl. Math., (2018).

Arshad, S., Baleanu, D., Bu, W. & Tang, Y. Effects of HIV infection on CD4+ T-cell population based on a fractional-order model. Adv. Diff. Equ. 2017(1), 1–14 (2017).

Perelson, A. S. & Nelson, P. W. Mathematical analysis of HIV-1 dynamics in vivo. SIAM Rev. 41(1), 3–44 (1999).

Perelson, A.S., 1989. Modeling the interaction of the immune system with HIV. In Mathematical and statistical approaches to AIDS epidemiology (pp. 350-370). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Caputo, M. & Fabrizio, M. A new definition of fractional derivative without singular kernel. Progr. Fract. Differ. Appl. 1(2), 1–13 (2015).

Atangana, A. & Baleanu, D. New fractional derivatives with nonlocal and non-singular kernel: theory and application to heat transfer model. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03408 (2016).

Atangana, A. & Owolabi, K. M. New numerical approach for fractional differential equations. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 13(1), 3 (2018).

Funding

Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu (Knowledge Transfer Center) & Hasso Plattner Foundation research grants LBUS-HPI-ERG-2023-05.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated equally to the conceptualization, investigation, analysis, original draught writing, review, and editing of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Funding section. “Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu through research grant LBUS-IRG-2023-09.” now reads: “Project financed by Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu (Knowledge Transfer Center) & Hasso Plattner Foundation research grants LBUS-HPI-ERG-2023-05”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shutaywi, M., Shah, Z., Vrinceanu, N. et al. Exploring the dynamics of HIV and CD4+ T-cells with non-integer derivatives involving nonsingular and nonlocal kernel. Sci Rep 14, 24506 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73580-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73580-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The extended-\(\left( \frac{G'}{G}\right)\)-expansion method and new exact solutions for the conformable space-time fractional diffusive predator-prey system

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Modeling and analyzing the dynamics of brucellosis disease with vaccination in the fractional derivative under real cases

Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computing (2025)

-

Dynamic analysis and optimal control of competitive information dissemination model

Scientific Reports (2024)