Abstract

Aggressive pecking is an important welfare and production efficiency issue in poultry farming. The precise mechanisms underlying the occurrence of aggressive pecking remain poorly understood. In this study, we selected Sansui ducks that performed aggressive pecking and ducks that did not perform aggressive pecking from video recordings. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses of the whole brains of aggressive pecking ducks and normal ducks revealed 504 differentially expressed genes and 5 differentially altered metabolites (adenosine, guanidinopropionic acid, Met-Leu, Glu-Ile and 5,6,8-trihydroxy-2-methylbenzo[g]chromen-4-one). By jointly analysing the transcriptomics and metabolomics results, we discovered 8 candidate genes (ADCYAP1, GAL, EDN2, EDN1, MC5R, S1PR4, LOC113843450, and IAPP) and one candidate metabolite (adenosine) that regulates aggressive pecking behaviour in ducks. The candidate genes and metabolites may be involved in regulating aggressive pecking behaviour by inducing neurodegeneration and disrupting neural excitatory-inhibitory homeostasis, which in turn affects central nervous system function in aggressive pecking and normal ducks. Our findings provide a new reference for revealing the underlying mechanism of aggressive pecking behaviour in ducks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ducks constitute one of the major sources of animal protein production. For the purpose of increasing duck production and achieving profitability, managers need to improve the performance of ducks through their housing system1. However, housing systems are among the key factors affecting animal welfare. An elevated stocking density diminishes the available space for individual poultry, thereby reducing the living resources at their disposal. As a consequence, poultry are rendered more susceptible to distress, with the potential for a higher level of stress resulting in a greater likelihood of aggressive behaviour2. Aggression is defined as the behaviour of individual animals fighting each other under conditions conducive to individual survival. This competitive behaviour is influenced by multiple factors, including food, mates, social status, and others. The aggressive behaviours of poultry are primarily categorized as threatening, chasing, aggressive pecking (AP) and clawing3.

AP behaviour, which is usually directed at the head of the receiving bird in poultry, is an important part of their daily life, and is used to some extent to build and maintain social hierarchies in the group4. However, AP is also an important welfare and production efficiency issue in poultry farming5. If not stopped in time, AP can cause social stress, physical injury, and death, leading to serious economic loss6. A number of environmental factors have been identified as influencing AP, including light7, stocking density8, food9, feeding methods10, and group size11. To date, the underlying mechanisms responsible for the occurrence of AP in ducks remain poorly understood. Although some previous studies have shown that AP is associated with postsynaptic signalling through genome-wide association analyses12 and microarray analyses13, the transcriptomics and metabolome of AP in ducks remain unexplored. Transcriptomics is a powerful technology that provides insight into the complexity of gene expression in organisms. The metabolome is downstream of gene regulatory networks and protein action networks, and provides terminal information about biology. By integrating transcriptomics and metabolomics studies, the underlying mechanisms of AP can be better revealed. Therefore, exploring the mechanism of AP behaviour in ducks through transcriptome and metabolome profiling is useful for preventing and reducing the occurrence of excessive AP behaviour in intensive farming.

In this study, we observed the AP of Sansui ducks on video and selected Sansui ducks that performed AP and ducks that did not perform AP. We subsequently screened the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and differentially altered metabolites (DAMs) in the whole brains of AP ducks and Normal ducks by transcriptomics and metabolomics. Finally, we identified 8 candidate genes and 1 candidate metabolite by combining the results of transcriptomics and metabolomics. These findings will contribute to our understanding of the mechanisms underlying AP behaviour in ducks.

Results

Transcriptome quality assessment

The quality control results of the whole-brain transcriptomes are listed in Table 1. Six ducks from the AP and Normal group were used to construct cDNA libraries. A total of more than 34 million valid reads were obtained from each library. The GC contents of all the samples ranged from 46.5 to 47%, with the percentage of the Q20 bases ranged from 98.43 to 98.72%, and the percentage of the Q30 bases ranged from 94.02 to 95.02%.

Transcriptome analyses

As shown in the principal component analyses (PCA) plot (Fig. 1a), the cumulative values of PCA1 and PCA2 were 95.58%, indicating the presence of DEGs in the AP and Normal groups. To explore DEGs in the whole brains of AP ducks and Normal ducks, gene expression levels were quantified by fragment per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). A total of 504 DEGs (315 upregulated DEGs and 189 downregulated DEGs, Supplementary Table S1) were identified between the AP and Normal groups (Fig. 1b). These DEGs are potentially regulators of AP behaviour. In addition, a clustered heatmap was generated based on the expression levels of the DEGs (Fig. 1c).

Gene enrichment analyses

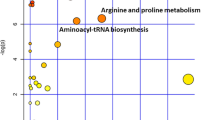

To investigate the potential roles of these DEGs, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis were performed as well as Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. KEGG enrichment analyses (Fig. 2a) showed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in ribosomes, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, and fatty acid elongation pathways. In addition, GO enrichment analysis (Fig. 2b) showed that the DEGs were significantly enriched in biological processes such as translation and retinol metabolic process. GO enrichment was also observed for cellular components and molecular functions, which included GO terms such as ribosomes, structural components of ribosomes, extracellular region and thyroid hormone binding.

Metabolome analysis

In the PCA plot (Fig. 3a), the cumulative values of the horizontal (PCA1) and vertical (PCA2) coordinates were 97.91% indicating that DAMs were present in the AP and Normal groups. In addition, the Partial Least Squares Discrimination Analyses (PLSDA) score plot explained 64.55% of the variation between the AP and Normal groups (Fig. 3b). The R2 value of the PLSDA model was 0.6858 and the Q2 value was less than 0, indicating that the PLSDA model was not overfit (Fig. 3c). Five DAMs (Supplementary Table S2) were observed between the AP and Normal groups (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, a clustering heatmap was drawn based on the expression levels of the DAMs (Fig. 3e). To further identify the roles of specific signalling pathways in AP behaviour, KEGG pathway analyses was performed on DAMs from AP and Normal ducks. A total of 13 KEGG pathways were significantly enriched in DAMs (Fig. 3f), including morphine addiction, cGMP-PKG signaling pathway, alcoholism, regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes, sphingolipid signaling pathway, vascular smooth muscle contraction, renin secretion, cAMP signaling pathway, parkinson disease, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, nucleotide metabolism, purine metabolism, and ABC transporters.

Combined analysis of metabolome and transcriptome

To further identify candidate genes and metabolites, the results of the transcriptome and metabolome were analyzed jointly. As shown in Fig. 4, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway was identical between DEGs and DAMs. Through the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, 8 candidate genes including ADCYAP1 (Adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 1), GAL (Galanin), EDN2 (Endothelin 2), EDN1 (Endothelin 1), MC5R (Melanocortin receptor 5), S1PR4 (Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 4), LOC113843450, and IAPP (Islet Amyloid Polypeptide), and one candidate metabolite (adenosine) were identified (Table 2).

qRT-PCR validation of RNA-Seq results

To test the results of RNA-seq, 8 DEGs in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway were analysed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) as shown in Fig. 5. The results showed that the expression trends determined by qRT-PCR were consistent with the RNA-Seq results, while a high correlation coefficient (R = 0.8452) and a significant P value (P = 0.0082) indicated that the RNA-seq results were reliable.

Discussion

AP in poultry is an important way to establish and maintain social status. However, aggression also represents a source of stress for both dominant and subordinate animals14. Nerve cells are extremely sensitive to stress, and many studies have shown that stress causes progressive losses in nerve cell structure and function, affecting central nervous system (CNS) function and ultimately leading to many neurodegenerative disorders such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia15. Patients with neurodegenerative disorders often exhibit cognitive deficits, hyperactivity, and high aggression16. In studies of birds, it has also been reported that stress causes damage to nerve cells, ultimately leading to a decrease in synaptic connections which affects an individual’s ability to learn, remember, and cope with stress17,18.

Nervous system dysfunction is considered an important factor that influences aggressive behaviour. A multitude of studies have reported that serotonin and dopamine, two key neurotransmitters, are involved in regulating aggressive behaviour19. However, no significant differences in the receptor genes of serotonin and dopamine were observed between the AP and Normal groups in our transcriptome results, which is in agreement with the results of a previous study in chickens13. Due to behavioural traits that are typically influenced by a large number of genes working together, we suppose that other alleles to some extent supersede the role of these neurotransmitter receptor genes in the regulation of AP. Additionally, Buitenhuis et al.13 demonstrated that GO terms such as synaptosomes and glutamate receptor binding may be related to AP behaviour by affecting memory formation. According to our transcriptome results, the most significantly enriched GO terms were translation, ribosomes, and structural components of ribosomes. Memory is a fundamental cognitive process that requires protein synthesis to consolidate memories20. Ribosomes are important macromolecular machines because they are associated with protein synthesis in cells. Previous studies have shown that neuronal protein synthesis occurs near synapses21. As a result of altered ribosome function, brain and behaviour changes, such as changes in memory functions, may follow in AP and Normal ducks. In addition, Lutz et al.12 showed that GNG2 (G protein subunit gamma 2) may be related to the monomanine signaling pathway, which is involved in AP behaviour. Although GNG2 was screened in our study, the log2(fold change) was 0.57 with a p-value of 0.15, which was not statistically significant. A comparison of our study results with literature reports revealed some inconsistent results, possibly because the test animals in the previous study were laying hens from a feather pecking selection line, whereas the test animals employed in our study were commercial ducks.

Furthermore, the combination of transcriptomic and metabolomic KEGG enrichment results in this study revealed one pathway, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, which was common to both the DEGs and the DAMs (Fig. 4). Previous studies have shown that neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction22 could influence memory formation. Through the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway, 8 candidate genes and 1 candidate metabolite were identified (Table 2). Neurodegeneration has been linked to impairments in memory and cognitive function23. Neuroinflammation is one of the hallmarks of neurodegeneration. Activated microglia and astrocytes produce proinflammatory factors and stimulate other immune cells to produce neurotrophic factors and inflammatory mediators24. However, overactivated microglia gradually shift from providing nutritional support and repairing nerve cells to becoming dysfunctional25. This response further recruits peripheral innate immune cells and adaptive immune cells across the blood-brain barrier, ultimately leading to cognitive and mood disorders26. S1PR4 is a member of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor family, that is located in the active zone of nerve endings and regulates neuronal activity27. Furthermore, S1PR4 can influence CNS function by modulating blood-brain barrier permeability28. ADCYAP1 is a neuropeptide involved in neurotransmission in the CNS, and has also been shown to inhibit the production of proinflammatory factors by lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia to modulate the occurrence of neuroinflammation29. In addition, ADCYAP1 can alleviate pain in the acute phase of peripheral nerve injury and promote the regeneration of nerve axons30. Multiple sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the CNS. IAPP is an amyloid polypeptide that can exert toxic effects by inducing neuroinflammation in the CNS31; IAPP can also lead to neuronal apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction through the production of reactive oxygen species32. GAL is a class of neuropeptides that exert protective effects on the CNS. For example, under kainate (a neurotoxic amino acid) induced injury, the hippocampal neuronal cell death rate was greater in GAL-knockout mice than in wild-type mice, whereas in GAL-overexpressing mice, the hippocampal neuronal cell death rate was significantly lower than that in wild-type mice33. In addition, it has been shown that GAL knockout mice suffer from the loss of hippocampus-mediated spatial memory capacity34. The melanocortin system has been linked to memory, nociception, mood disorders and addiction35. MC5R is one of the receptors for melanocortin, and a study showed that MC5R expression was upregulated 3-4-fold in the hippocampal and midbrain regions of young rats compared with older rats36. This suggested cognitive decline occurs in rats with downregulated levels of MC5R expression. EDN1 and EDN2 are genes that encode endothelin and are associated with neurotransmission37. One study indicated that exposure of astrocytes to EDN1 and EDN2 significantly reduced the expression of glutamate transporter proteins38, whereas decreased glutamate transporter protein expression may increase glutamate levels39. Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS. High levels of glutamate can overstimulate neurons, leading to neuronal death40. In addition, LOC113843450 has been reported in a few studies, though its effects on aggressive behaviour remain unclear.

Adenosine, a metabolite of adenosine triphosphate, is involved in the regulation of many physiological activities in the body. In the context of neurological injury, adenosine may exert neuroprotective effects; for example, the activation of the adenosine A1 receptor in ischaemie stroke mice enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and exerts neuroprotective effects41. Alternatively, adenosine can act as an inhibitory neuromodulator responsible for feedback regulation of excitatory synaptic activity. For example, the activation of adenosine A1 receptor at the presynaptic membrane inhibits the release of neurotransmitters such as glutamate42, 5-HT43, and dopamine44. In contrast, activation of the adenosine A2a receptor promotes the release of glutamate, norepinephrine45 and 5-HT46.

In conclusion, the 8 candidate genes and adenosine enriched in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway in the present study may affect the CNS function of AP ducks and Normal ducks by inducing neurodegeneration and disrupting the balance of neural excitation and inhibition, which might cause differences in the AP phenotype.

Methods

Animals, living conditions and AP observations

Thirty-six 17-week-old Sansui ducks were randomly divided into three cages (0.65 m H x 0.8 m W x 1.2 m D, 0.08 m2 per duck). Each duck was given a polyethylene collar of a different colour, while a camera was placed above the cage to record the number of AP. In this study, the observation of AP was divided into two phases: a preobservation period and a formal observation period, with a 14-day acclimatization period for each observation. The preobservation period was 3 days, and the number of AP was counted from 9:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. and from 15:00 p.m. to 16:00 p.m. During the preobservation period, a duck was defined as an AP duck when it gave more than one AP, and a duck was defined as a Normal duck when it gave zero AP. After preobservation, 12 AP ducks and 12 Normal ducks were then divided into two cages for formal observation, and the number of AP was counted by video for seven consecutive days (every day from 9:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. and from 15:00 p.m. to 16:00 p.m.). At the end of the formal observation period, three AP ducks with the highest number of occurrences of AP were selected, and three Normal ducks without AP were selected. The animals were subsequently euthanized by cervical dislocation, and their whole brains were homogenized separately using a tissue homogenizer (QK-1B, Jingxin, China), and preserved at -80℃ for transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses. In this study, the ducks were fed twice a day (8 a.m. and 17 p.m.), had free access to water, and were maintained under a 18 L: 6D photoperiod.

RNA extraction, cDNA library construction, and sequencing

The total RNA of 6 whole brain samples, 3 from Normal group and 3 from AP group, were extracted with TRIzol reagent (15596018, Thermo Fisher, USA). The total RNA quantity and purity were analyses with a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA, USA) and a NanoDrop ND-2000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE, USA), and RNA samples with RNA integrity numbers > 7.0 were used to construct sequencing library. After total RNA was extracted, mRNA was purified from the total RNA using Dynabeads Oligo (dT) 25 (61005, Thermo Fisher, CA, USA) through two rounds of purification. After purification, the mRNA was fragmented into short fragments using a Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (E6150S, NEB, USA). Then the short RNA fragments were reverse-transcribed to cDNA with SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (1896649, Invitrogen, USA), and the cDNA was used to synthesise U-tagged second-strand DNAs with DNA polymerase I (M0209, NEB, USA), RNase H (M0297, NEB, USA) and dUTP Solution (R0133, Thermo Fisher, USA). An A base was added to the blunt end of each strand in preparation for ligation to the index adapters, as each adapter contains a T base pendant for ligating the adaptor to the A-tailed fragment DNA. Dual-index adapters were ligated to the fragments, and size selection was performed with AMPureXP beads. After heat-labile UDG enzyme (M0280, NEB, USA) treatment of the U-labelled second-stranded DNAs, the ligated products were amplified by PCR. The average insert size for the cDNA library was 300 ± 50 bp. Finally, paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina Novaseq™ 6000 (Illumina, USA) according to standard operation in PE150 sequencing mode. RNA sequencing was carried out by LC Bio Technology Co.,Ltd.

RNA-seq data analyses

Further filtering of the reads was performed using Cutadapt (V1.9) and sequence quality was verified in FastQC (V0.11.9). Afterwards, we aligned reads from all samples to the Anas platyrhynchos reference genome using HISAT2 (V2.2.1) and transcriptome was assembled for each individual sample using StringTie (V2.1.6), followed by a composite transcriptome reconstruction using gffcompare (V0.9.8). Transcript expression levels and FPKM values were determined using StringTie and Ballgown (V2.30.0), and differential expression analyses were performed based on the FPKM values using DESeq2 software (V1.10), with thresholds of P-values < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1 to identify genes as DEGs. The DEGs were subsequently subjected to enrichment analyses of GO functions (http://www.geneontology.org/) and KEGG pathways47. PCA was performed with the princomp function of R software (V 3.6).

Metabolite extraction and nontargeted metabolomics

Fifty milligrams of each whole brain sample, 3 from Normal group and 3 from AP group, was separately added to a centrifuge tube with 500 µL of precooled 80% methanol (A-456-4, Thermo Fisher, USA) and homogenized (50 Hz) for 60 s. The centrifuge tube subsequently was placed at -20 ℃ for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 4 ℃ and 20,000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to another centrifugal tube and vacuum dried. Then, the supernatant was redissolved in 100µL of 80% methanol, and centrifuged at 4 ℃ and 20,000 g for 15 min and stored at -80 °C prior to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric (LC-MS) analyses. In addition, pooled QC samples were also prepared by combining 10 µL of each extraction mixture. LC-MS was carried out by LC Bio Technology Co.,Ltd.

LC analyses was performed on a Vanquish Flex UPLC System (Thermo Fisher, Germany) and chromatography was carried out with an ACQUITY UPLC T3 (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm, Waters, UK). The column temperature was 40 °C, and the flow rate was 0.30 mL/min. Mobile phase A was 5 mmol/L ammonium acetate plus 5 mmol/L acetic acid, and mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The gradient elution conditions were set as follows: 0–0.8 min, 2% B; 0.8–2.8 min, 2–70% B; 2.8–5.3 min, 70–90% B; 5.3–5.9 min, 90–100% B; 5.9–7.5 min, 100% B; 7.5–7.6 min, 100–2% B; and 7.6–10.0 min, 2%. MS detection of metabolites was performed on a Q Exactive instrument (Thermo Fisher, Germany), which was operated in positive (4000 V) and negative (4500 V) ionization modes, and the temperature of the electrospray ionization source was 350 °C. Precursor spectra were acquired at a resolution of 70,000 to achieve an AGC target of 3e6. The maximum injection time was set to 100 ms. The top 3 signal ions with signal accumulation intensities above 100,000 were then selected from the primary spectrum for a secondary fragmentation scan. The resolution of the secondary level was 17,500 and the maximum injection time was set to 50 ms.

Metabolome data analyses

The MS data were preprocessed in the XCMS package of R software for peak picking, peak grouping, retention time correction, and second peak grouping. The metabolites were characterized by combining the retention time and mass/ charge number of ion data for each ion using the KEGG database. The criterion for significant DAMs selection was P value < 0.05.

PCA was performed using metaX package of R software, PLSDA was performed in the ropls package, and hierarchical clustering was performed using the pheatmap package.

Validation of RNA-seq Data by qRT-PCR

To test the reliability of the RNA-seq results, 8 DEGs in the neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction pathway were selected for qRT-PCR analyses. GAPDH (Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was used as an internal marker to normalize the expression levels. The primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table 3. Total RNA samples were reverse transcribed to cDNA using a RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synhesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, K16225). Gene expression was analyzed using a CFX96 (Bio-Rad, USA) and 2×RealStar Fast SYBR qPCR Mix (Genstar, A301). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and relative quantification of gene expression was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Statistical analyses

The qRT-PCR data were statistically analysed and plotted using Excel 2021 and GraphPad Prism (V8.0). The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between RNA-seq and qRT-PCR data. The Data were expressed as mean ± SDs. Student’s t-test was used to analyze the differences in the RNA-seq data and metabolome data. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Data availability

The sequence reads are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Bioproject database (Ascension number PRJNA1122767). The other datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hamid, S., Saleem, A., Youssef, M., Mohammed, H. & Abdelaty, A. Influence of Housing systems on duck Behavior and Welfare. J. Adv. Veterinary Anim. Res.7, 407 (2020).

Uçar, A. The effects of stocking density on growth, Morphological Development, Behavior, and Welfare parameters in Pheasants (Phasianus Colchicus). Trop. Anim. Health Pro 56, (2024).

Nie, C., Ban, L., Ning, Z. & Qu, L. Feather Colour affects the aggressive behaviour of chickens with the same genotype on the Dominant White (I) locus. Plos One. 14, e215921 (2019).

Strauss, E. D., Curley, J. P., Shizuka, D. & Hobson, E. A. The Centennial of the Pecking Order: current state and future prospects for the study of Dominance hierarchies. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.377, 20200432 (2022).

Hanh, H. Q. et al. Effects of stocking density in Group cages on Egg Production, profitability, and aggressive pecking of hens. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci.26, 374–385 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Aggressive Behaviour in Chicken. Sci. Rep.6, 30981 (2016).

Ozkan, S. et al. Effects of incubation lighting with Green or White Light on Brown layers: hatching performance, feather pecking and hypothalamic expressions of genes related with photoreception, serotonin, and stress systems. Poult. Sci.101, 102114 (2022).

Pettit-Riley, R., Estevez, I. & Russek-Cohen, E. Effects of Crowding and Access to Perches on aggressive Behaviour in broilers. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci.79, 11–25 (2002).

Savory, C. J., Mann, J. S. & MaCleod, M. G. Incidence of pecking damage in growing bantams in relation to Food Form, Group size, Stocking Density, Dietary Tryptophan Concentration and Dietary protein source. Brit Poult. Sci.40, 579–584 (1999).

Morrissey, K. L. H. et al. The effect of dietary alterations during rearing on growth, Productivity, and behavior in broiler Breeder females. Poult. Sci.93, 285–295 (2014).

WECHSLER, B. & SCHMID, I. Aggressive pecking by males in breeding groups of Japanese quail (Coturnix Japonica). Brit Poult. Sci.39(3), 333–339 (1998).

Lutz, V. et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study in a Large F2-Cross of Laying Hens Reveals Novel Genomic Regions Associated with Feather Pecking and Aggressive Pecking Behavior. Genet. Sel. Evol.49, (2017).

Buitenhuis, B., Hedegaard, J., Janss, L. & Sørensen, P. Differentially expressed genes for aggressive pecking Behaviour in laying hens. BMC Genom.10, 544 (2009).

Carvalho, R. R., Palme, R. & Da, S. V. A. An Integrated Analyses of Social Stress in laying hens: the Interaction between Physiology, Behaviour, and Hierarchy. Behav. Processes. 149, 43–51 (2018).

Gulyaeva, N. V. Functional neurochemistry of the ventral and dorsal Hippocampus: stress, Depression, Dementia and remote hippocampal damage. Neurochem Res.44, 1306–1322 (2019).

Lee, S. et al. Trimethyltin-Induced hippocampal neurodegeneration: a mechanism-based review. Brain Res. Bull.125, 187–199 (2016).

Kumar, A., Tamta, K., Arya, H. & Maurya, R. C. Acute-stress induces the structural plasticity in hippocampal neurons of 15 and 30-Day-old chick, Gallus Gallus Domesticus. Ann. Anat.245, 151996 (2023).

Arya, H., Tamta, K., Kumar, A., Arya, S. & Maurya, R. C. Unpredictable chronic mild stress shows neuronal remodeling in Multipolar Projection Neurons of Hippocampal Complex in Postnatal Chicks. Anat. Sci. Int.99, 254–267 (2024).

de Almeida, R. M. M., Ferrari, P. F., Parmigiani, S. & Miczek, K. A. Escalated aggressive behavior: dopamine, serotonin and Gaba. Eur. J. Pharmacol.526, 51–64 (2005).

McGaugh, J. L. Memory–A century of consolidation. Science287(5451), 248–251 (2000).

Hafner, A. S., Donlin-Asp, P. G., Leitch, B., Herzog, E. & Schuman, E. M. Local Protein Synthesis is a Ubiquitous Feature of Neuronal Pre- And Postsynaptic Compartments. Science.364(6441), (2019).

Guan, S. et al. Mechanism of Microwave Radiation-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment Based On Hippocampal Metabolomics. Brain Sci. 14, (2024).

Olajide, O. J., Suvanto, M. E. & Chapman, C. A. Molecular Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration in the Entorhinal Cortex that Underlie its Selective Vulnerability During the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Open.10(1), (2021).

Gorlova, A. et al. Understanding the Role of Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation and Abnormal Myelination in Excessive Aggression Associated with Depression: Recent Input From Mechanistic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Microglia in Depression: an overview of Microglia in the Pathogenesis and treatment of Depression. J. Neuroinflammation19(1), (2022).

Kumar, A. & Loane, D. J. Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury: opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Brain Behav. Immun.26, 1191–1201 (2012).

Skoug, C., Martinsson, I., Gouras, G. K., Meissner, A. & Duarte, J. Sphingosine 1-Phoshpate receptors are located in synapses and control spontaneous activity of mouse neurons in culture. Neurochem Res.47, 3114–3125 (2022).

Hansen, L. et al. Endothelial sphingosine-1-Phosphate receptor 4 regulates blood-brain barrier permeability and promotes a homeostatic endothelial phenotype. J. Neurosci.42, 1908–1929 (2022).

Delgado, M., Leceta, J. & Ganea, D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and Pituitary Adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit the production of Inflammatory mediators by activated Microglia. J. Leukoc. Biol.73, 155–164 (2003).

Chen, Q. et al. Unveiling Adcyap1 as a protective factor linking Pain and nerve regeneration through single-cell rna sequencing of rat dorsal Root ganglion neurons. Bmc Biol.21(1), 235 (2023).

Bortoletto, A. S. & Parchem, R. J. A pancreatic player in dementia: pathological role for islet amyloid polypeptide Accumulation in the brain. Neural Regen Res.18(10), 2141–2146 (2023).

Zhang, N. et al. Influence of human amylin on the membrane Stability of Rat primary hippocampal neurons. Aging (Albany NY)12(10), 8923–8938 (2020).

Elliott-Hunt, C. R. et al. Galanin acts as a neuroprotective factor to the Hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A101(14), 5105–5110 (2004).

Massey, P. V., Warburton, E. C., Wynick, D., Brown, M. W. & Bashir, Z. I. Galanin regulates spatial memory but not visual recognition memory or synaptic plasticity in Perirhinal Cortex. Neuropharmacology.44(1), 40–48 (2003).

Caruso, V., Lagerström, M. C., Olszewski, P. K., Fredriksson, R. & Schiöth, H. B. Synaptic Changes Induced by Melanocortin Signalling. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.15(2), 98–110 (2014).

Zhou, Y. et al. Aged Brains Express Less Melanocortin Receptors, Which Correlates with Age-Related Decline of Cognitive Functions. Molecules26, (2021).

Khimji, A. K. & Rockey, D. C. Endothelin–Biology and Disease. Cell. Signal.22, 1615–1625 (2010).

Rozyczka, J., Figiel, M. & Engele, J. Endothelins negatively regulate glial glutamate transporter expression. Brain Pathol.14, 406–414 (2004).

Sun, W., Shchepakin, D., Kalachev, L. V. & Kavanaugh, M. P. Glutamate transporter control of ambient glutamate levels. Neurochem Int.73, 146–151 (2014).

Olivares-Bañuelos, T. N., Chí-Castañeda, D. & Ortega, A. Glutamate transporters: gene expression regulation and Signaling properties. Neuropharmacology161, 107550 (2019).

Han, W., Zhang, E., Tian, Y., Wang, S. & Chen, Y. Adenosine receptor a1 enhanced mitochondrial Biogenesis and Exerted Neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia through Pgc-1Α. Exp. Brain Res.241, 1471–1488 (2023).

Barrie, A. P. & Nicholls, D. G. Adenosine a1 receptor inhibition of glutamate exocytosis and protein kinase C-Mediated decoupling. J. Neurochem. 60, 1081–1086 (1993).

Okada, M. et al. Differential effects of Adenosine receptor subtypes on release and reuptake of hippocampal serotonin. Eur. J. Neurosci.11, 1–9 (1999).

Borycz, J. et al. Differential Glutamate-Dependent and Glutamate-Independent Adenosine a1 receptor-mediated modulation of dopamine release in different Striatal compartments. J. Neurochem. 101, 355–363 (2007).

Matsumoto, J. P., Almeida, M. G., Castilho-Martins, E. A., Costa, M. A. & Fior-Chadi, D. R. Protein kinase a mediates Adenosine a2a receptor modulation of Neurotransmitter Release Via Synapsin I phosphorylation in cultured cells from Medulla Oblongata. Neurosci. Res.85, 1–11 (2014).

Barraco, R. A., Helfman, C. C. & Anderson, G. F. Augmented release of serotonin by Adenosine a2a receptor activation and desensitization by Cgs 21680 in the rat nucleus Tractus Solitarius. Brain Res.733, 155–161 (1996).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S. & Kegg,. Kyoto Encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res.28, 27–30 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 31960682), the Chinese Government Grant for Supporting the Development of Local Science and Technology (No. [2019]4021), Agricultural Major Special Project of Guizhou Province (No. [2019]5203), the Special Research Projects of Guizhou Province (No. [2020]1Y041), and the Guizhou University College Students SRT Plan Project (No. GD SRT 20).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z. and S.Y. contributed to research conceptualization and design. B.Z., A.L. and S.Y. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. B.Z., J.Z., B.Y. and F.L. conducted behavioral observation experiments, data collection and analyses. S.Y. secured funding to undertake the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the approval of the Guizhou University Subcommittee of Experimental Animal Ethics (No.EAE-GZU-2022-E048). This study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as well as the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, B., Zhu, J., Liu, A. et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis based on different aggressive pecking phenotype in duck. Sci Rep 14, 22321 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73726-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-73726-9