Abstract

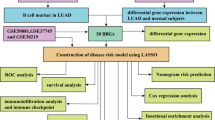

Angiogenesis, metastasis, and resistance to therapy are all facilitated by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). A CAF-based risk signature can be used to predict patients’ prognoses for Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) based on CAF characteristics. The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database was used to gather signal-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data for this investigation. The GEO and TCGA databases were used to gather bulk RNA-seq and microarray data for LUAD. The scRNA-seq data were analyzed using the Seurat R program based on the CAF markers. Our goal was to use differential expression analysis to discover differentially expressed genes (DEGs) across normal and tumor samples in the TCGA dataset. Pearson correlation analysis was utilized to discover prognostic genes related with CAF, followed by univariate Cox regression analysis. Using Lasso regression, a risk signature based on CAF-related prognostic genes was created. A nomogram model was created based on the clinical and pathological aspects. 5 CAF clusters were identified in LUAD, 4 of which were associated with prognosis. From 2811 DEGs, 1002 genes were found to be significantly correlated with CAF clusters, which led to the creation of a risk signature with 8 genes. These 8 genes were primarily connected with 41 pathways, such as antigen paocessing and presentation, apoptosis, and cell cycle. Meanwhile, the risk signature was significantly associated with stromal and immune scores, as well as some immune cells. Multivariate analysis revealed that risk signature was an independent prognostic factor for LUAD, and its value in predicting immunotherapeutic outcomes was confirmed. A novel nomogram integrating the stage and CAF-based risk signature was constructed, which exhibited favorable predictability and reliability in the prognosis prediction of LUAD. CAF-based risk signatures can be effective in predicting the prognosis of LUAD, and they may provide new strategies for cancer treatments by interpreting the response of LUAD to immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lung cancer is estimated to contribute to 25% of cancer-associated deaths, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) alone accounts for 85% of cases1, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and squamous carcinoma are two major subtypes of NSCLC. Metastatic LUAD treatment has been revolutionized by immunotherapy since it was approved by the FDA in 2015. Despite many factors associated with intrinsic resistance to immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), LUAD has been hampered by a lack of predictive biomarkers and limited understanding of how ICIs affect the disease3. It was possible to predict the immunotherapy clinical outcomes of LUAD using omic data-derived signatures4. Consequently, multigene signatures can be valuable for predicting LUAD outcomes.

Tumor microenvironment (TME) is a specialized ecosystem of host components designed by tumor cells to support the development and metastasis of tumors5. There are diverse immune cell types in the TME, as well as cancer-associated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, and other types of cells residing in the tissue. Host cells were once thought to play no role in tumorigenesis, but are now known to play a crucial role in the development of cancer6. In order to understand the spatial and temporal regulation of immune therapeutic interventions, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of the diversity of immune cells, stromal components, repertoire profiling, and the neoantigen prediction of TME5. TME is dominated by cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) that affect cancer features7. As a result of growth factors, inflammatory ligands, and extracellular matrix proteins, they promote the proliferation of cancer cells, the resistance to therapy, and the exclusion of the immune system8. With CAFs being highly heterogeneous, it remains unclear how cancer treatments can be personalized based on CAFs in a patient’s tumor as they are highly heterogeneous9. Although many studies have investigated CAF characteristics in LUAD, the relationship between CAF characteristics and prognosis and immunotherapy response remains poorly understood10,11,12.

From the TCGA databases, we obtained LUAD single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data and transcriptome data. In this study, we distinguished CAF subclusters and identified CAF-based risk signatures for patients with LUAD who received immunotherapy. An analysis of the immunologic landscape and responsiveness to immunotherapy underlying the CAF-based signature was conducted to determine its clinical relevance. A novel nomogram has been created to facilitate the clinical application of CAF features in LUAD prognosis combining the CAF-based risk signature and clinicopathological features. The study may provide new insights into the pathophysiology of LUAD, allowing for more tailored treatments and better outcomes for patients.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition and processing

In addition to the GEO database, scRNA-seq data for GSE149655 were downloaded, including 2 samples of LUAD carrying KRAS mutations. First, single cells were screened with each gene expressed in at least three cells and each cell expressing at least 250 genes for scRNA-seq data. For evaluation of mitochondrial and RNA proportions, we used the PercentageFeatureSet function in the Seurat R package. To further screen the single cells, each cell had to express at least 5000 genes with a unique molecular identifier (UMI) greater than 100. Finally, a total of 6410 cells were remained. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database provided transcriptome, single-nucleotide variant (SNV) and copy number variant (CNV) data, and clinical information about LUAD. A total of 500 tumor samples and 59 para-cancerous samples were included in the transcriptome analysis after removing samples without survival data or outcome status. We downloaded the GSE3141, GSE31210, GSE37745, GSE50081 and GSE68465 cohort from the GEO database as a validation cohort after removing normal tissue samples and tumor samples without follow-up information. Literature searches were conducted for ten cancer-related pathways (Cell Cycle, HIPPO, MYC, NOTCH, NRF1, PI3K, TGF-Beta, RAS, TP53, and WNT)13.

Definition of CAF

A comprehensive CAF signature was characterized using the Seurat package using scRNA-seq data from LUAD. Firstly, we removed the cells with over 6000 or below 250 expressed genes, then we normalized the expression of these genes based on log ratios. Using the FindIntegration Anchors function, batch effects were eliminated for 4 samples. With a resolution of 0.2, the uniform manifold approximation and projection method was used for non-linear dimensional reduction. By using the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions, cells were clustered into different subgroups by using the functions of FindNeighbors and FindClusters (dim = 40 and resolution = 0.2). RunTSNE was then used to reduce the dimensions using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embeddings. Four marker genes were identified in fibroblasts, including ACTA2, FAP, PDGFRB, and NOTCH312,14,15,16. FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions were used to re-cluster the fibroblasts. Moreover, TSNE was used to lessen the dimensionality of fibroblast clusters. By comparing one CAF cluster with the others and using the FindAllMarkers function with logFC = 0.5, minpct = 0.35, and an adjusted p value < 0.05, we were able to determine the markers of each cluster. Using the clusterProfiler software(Version 4.12.6; https://yulab-smu.top/contribution-knowledge-mining/), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis was carried out on the marker genes of CAF clusters, the “clusterProfiler” R package was utilized to conduct KEGG analyses17,18,19. The CNV characteristics within CAF clusters were analyzed using the CopyKAT R package in order to differentiate between tumor cells and normal cells.

Identification of hub genes of CAF

By using the limma package, we first screened out differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between tumors and normal tissue with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2Fold Change|>1. We then identified the genes associated with CAF clusters by assessing the correlation between DEGs and CAF clusters with p < 0.001 and cor > 0.4. Using the survival package, we further identified genes related to prognosis with p < 0.05. With a stepwise regression method, we used cox regression analysis with the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (lasso) to compress the gene number. Our risk signature was constructed by multiplying ∑βi by Expi in the Cox multivariate model. A multivariate Cox model incorporates the coefficients for gene i and its expression level expi, where i denotes the gene involved in the risk signature, expi signifies the expression of gene i, and βi indicates the coefficients associated with gene i within the multivariate Cox framework. In order to identify high-risk and low-risk patients, zero-mean normalization was performed on the data. To analyze the predictive performance of the risk signature, the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was performed using the timeROC package. In the validation cohort, similar analyses were conducted.

Immune landscape analysis

To further explore the TME, the CIBERSORT algorithm was used to assess the proportions of 22 immune cell subtypes in the TCGA cohort, and the ESTIMATE algorithm was used to calculate the immune and stromal scores.

Construction of a risk signature and nomogram

We first perform univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis on clinicopathological and risk signatures in order to construct a nomogram model for clinical use. A nomogram was constructed using the rms package using variables with p > 0.05 in the multivariate Cox model. An evaluation of the model’s predictive accuracy was conducted using the calibration curve. An evaluation of the model’s reliability was conducted using decision curve analysis (DCA).

Responsiveness to immune checkpoint blocks

A transcriptomic analysis and clinical data matching were conducted on patients with urothelial carcinoma treated with an anti-PD-L1 agent (atezolizumab) from the IMvigor210 cohort (http://researchpub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies). In addition, GSE78220 cohort comprises transcriptomic data from pretreatment melanomas receiving anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibition therapy, which were also downloaded for determining whether the risk signature score can be used to predict responsiveness to immune checkpoint blocks (ICB).

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 3.6.3). Spearman correlation and Pearson correlation were used to analyze the correlation matrices. Comparing the two groups was carried out using the Wilcoxon test. A Log-rank test was used to compare survival differences using K-M curves. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

Results

scRNA-seq analysis of CAFs

A detailed analysis of data preprocessing can be found in Figure S1. Using four marker genes, including ACTA2, FAP, PDGFRB, and NOTCH3, nine CAF populations were identified after log-normalization and dimensionality reduction (Figures S1A, B). We extracted the cells of 5 CAF populations for further clustering and dimensionality reduction. We further clustered CAF populations using the same clustering algorithm and identified five clusters (Figures S1C, D). All five CAF clusters did not express the epithelial cell specific gene, supporting accurate CAF identification (Figure S2). UMAP plots of 4 sample distributions are shown in Fig. 1A. This resulted in the generation of five CAF clusters that were used for further analysis (Fig. 1B). 735 DEGs were identified among the 5 CAF clusters, and Fig. 1C shows the expression of the top 5 DEGs (determined as markers of CAF clusters) in the 5 clusters. Figure 1D illustrates the proportion of the 5 clusters in each cohort. According to Fig. 1E, these DEGs were enriched in multiple pathways, including ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, ribosome, and protein digestion and absorption. According to the CNV characteristic of the 5 CAF clusters, 347 tumor cells and 274 normal cells are present (Fig. 1F).

The identification of CAF clusters based on a scRNA-seq ddata of LUAD patients. (A) Distribution of 4 samples as represented by uMAP; (B) Distribution of five fibroblasts by uMAP after clustering; (C) Dot plot of top 5 gene expression markers of subgroups; (D) CAF proportion and number of subgroups for cancer tissue and metastatic lymph node cells; (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of 5 subsets of fibroblasts; (F) uMAP distribution map of malignant and non-malignant cells predicted by copykat package.

Cancer-related pathways expressed in CAF

The characteristics of ten tumor-related pathways in the five CAF clusters were investigated to examine the associations between CAF clusters and tumor progression. Figure 2 A shows the GSVA scores of ten tumor-related pathways in different CAF clusters. As shown in Fig. 2B, CAF_1 had a significant higher proportion of malignant cells than the other four clusters. Among the ten tumor-related pathways with in each CAF cluster, we found slight differences in GSVA scores between malignant and non-malignant cells (Fig. 2 C-G).

Characteristics of tumor-related pathways in CAF clusters. (A) Heatmap of 10 tumor-related pathways enriched in CAF cells; (B) Comparison of CAF clusters in malignant and non-malignant cells; Comparison of GSVA scores between malignant and non-malignant cells in CAF_0 (C), CAF_1 (D), CAF_2 (E), CAF_3 (F) and CAF_4 cluster (G). (wilcox.test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001and ns, not significant).

We first calculated the ssGSEA score of the marker genes (the top 5 DEGs of CAF clusters in Fig. 1C) of each CAF cluster based on the TCGA cohort to determine the associations between CAF clusters and prognosis. The CAF cluster scored significantly higher in normal samples than in tumor samples (Fig. 3A). By using the survminer R package, LUAD samples from the TCGA dataset were divided into high- and low-CAF score groups. CAF_1 and CAF_2 clusters had a better prognosis in the high-CAF score group than those in the low-CAF score group, CAF_0, CAF_3 and CAF_4 did not have any effect on the prognosis (Fig.3 B). CAF_1 and CAF_2 distribution in tumor tissue decreased as T stage increased, whereas CAF_0, CAF_3, and CAF_4 distribution did not change as T stage increased. CAF_1 and CAF_2 clusters may have lot impact on LUAD progression (Fig. 3 C).

Correlation between the five CAF clusters and prognosis for LUAD patients. (A) Comparison of five CAF scores in cancerous and normal tissue; (B) K-M curves for the high and low CAF scores in the CAF_0–4 cluster; (C) CAF scores for tumors at different stages in the CAF_0–4 cluster. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

Identification of hub genes involved in CAF

First, we screened out DEGs between tumor and normal tissues in order to construct a risk signature. Figure 4A shows that there were 1731 DEGs obtained, with 725 DEGs that were up-regulated and 1006 DEGs that were down-regulated (Fig. 4A). It was found that 416 genes were significantly associated with prognosis-related CAF clusters. Additionally, 234 genes exhibited prognostic values based on univariate Cox regression analysis (Fig. 4B). The number of genes was narrowed down by Lasso Cox regression analysis, and 8 genes retained lambda = 0.0185 (Fig. 4C). Finally, we included eight genes in the risk signature, including cell division cycle 25 C (CDC25C), exonuclease 1 (EXO1), cell cycle-related proteins cyclin B1 (CCNB1), dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 (DPYSL2), methyltransferase like 7 A (METTL7A), C-Type Lectin Domain Family 3 Member B (CLEC3B), brutons tyrosine kinase (BTK), glutamate receptor (GRIA) after multivariate Cox regression analysis using stepwise regression (Fig. 4E). The final 8-gene signature formula is as follows: RiskScore = -0.183*BTK + 0.051*CCNB1 + 0.116*CDC25C + 0.077* CLEC3B+-0.01*DPYSL2 + 0.086*EXO1+ -0.484*GRIA1+-0.04*METTL7A. After z-mean normalization, we calculated risk scores for each sample and divided them into high- and low-risk groups. According to Kaplan-Meier survival analyses, high-risk patients had significantly poorer survival outcomes (Fig. 4 F-K). In the 6 cohort (Fig. 4 F-K), the AUC values for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival were very good predictors of 3- and 5-year survival.

Identification of the hub predictive genes for constructing a risk signature. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes of cancer and normal tissues in TCGA cohort; (B) Univariate Cox regression analysis identified genes related to prognosis as volcano plots; (C) The trajectory of each independent variable with lambda; (D) Plots of the produced coefficient distributions for the logarithmic (lambda) series for parameter selection (lambda); (E) The multivariate Cox coefficients for each genes in the risk signature; (F-K) Multivariate Cox coefficients for each gene in the risk signature; ROC and K-M curves of risk model constructed by 8 genes in GSE3141 (F), GSE31210 (G), GSE37745 (H), GSE50081 (I), GSE68465 (J) and TCGA cohort (K).

Mutation and pathway analysis of the hub genes

Following that, we examined SNV mutations in the eight genes of the risk signature. There were more SNV mutations in BTK, EXO1 and GRIA1, while none were observed in CCNB1, CLEC3B and METTL7A (Fig. 5A). This analysis examined the probability of these key genes co-occurring with the 10 most mutated genes. In Fig. 5B, we found that EXO1, GRIA1 and CDC25C presented a significant co-occurrence probability. Combining the 10 oncogenic signaling pathways in TCGA, we found that RTK-RAS, WNT, NRF2, TGF-β and TP53 pathways were more affected, whereas the RAS, Hippo and TP53 pathways were more affected in the samples (Fig. 5C). By analyzing the correlations between the risk genes and a number of molecular signatures of LUAD, we further elucidated the associations between the risk genes and LUAD. According to the results, BTK, CLEC3B, DPYSL2 and METTL7A correlated negatively with Aneuploidy Score, Homologous Recombination Defects, Fraction Altered, Number of Segments, and Nonsilent Mutation Rate, while these were significantly positively correlated with CCNB1, CDC25C and EXO1 (Fig. 5D). We also examined the potential pathways associated with each risk gene. The correlation between these eight genes and 41 pathways is shown in Fig. 6A, these pathways include allograft rejection, antigen processing and presenation, and apoptosis, etc.

Identifies the mutation characteristics of the genes included in the risk signature. (A) A waterfall diagram of SNV mutations in 8 main genes; (B) Analysis of co-existence and mutual exclusion of key genes and the 10 most mutated genes in tumors; (C) Carcinogenic pathway analysis of LUAD in 10 oncogenic signaling pathways; (D) Heatmaps of 8 key genes correlated with Aneuploidy Score, Homologous Recombination Defects, Fraction Altered, Number of Segments, and Nonsilent Mutation Rate.

Relationship between hub genes and immunity

We found that BTK was significantly positive correlated with stromal score, immune score, and estimate score, while CCNB1, CDC25C and EXO1 was significantly negative correlated with stromal score, immune score, and estimate score (Fig. 7A). In addition, we observed significant differences in the expression of some risk genes between groups of immune cells with high and low expression (Fig. 7 C). A comparison of three scores in different expressed groups was conducted after grouping each gene according to its median expression value. There was a significant negative correlation between DPYSL2, GRIA1, and METTL7A and the majority of T cells according to the correlation analysis. Moreover, CCNB1, CDC25C, and HMGXB3 significantly positive correlated with M0 macrophages and Dendritic cells resting (Fig. 7D). Through the correlation analysis of immune cell abundance and gene expression, we found that BTK was significantly correlated with immune cell infiltration (Fig. 7E).

The relationship between risk genes and immune landscape. (A-B) Correlation matrix between 8 genes and immune score, stromal score and estimate score. (C) A comparison of the immune score (Wilcox.test) of the risk genes according to high and low expression of key genes. (D-E) CIBERSORT (D) and MCPcounter (E) analysis correlation between immune cell score and key genes. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001.

Response to PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy according to risk signature

T-cell immunotherapy has emerged as a promising anticancer treatment with synergistic survival benefits. As a result, we assessed the prognostic value of immunecheckpoint therapy risk signatures in the IMvigor210 and GSE78220 cohorts. In the IMvigor210 cohort, 348 patients showed varying degrees of response to anti-PD-L1 receptor blockers, including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD) (Fig. 8A). The percentage of SD/PD was higher in the high-risk group compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 8B). We observed that the high-risk group had significantly poorer overall survival (OS) outcomes than the low-risk group (Fig. 8C, p < 0.0001). The low-risk group of patients in the IMvigor210 cohort had significant clinical benefits and a significantly longer progression free survival (PFS) as compared with the high-risk group (Fig. 8D, p = 0.0054). In the GSE78220 cohort, we also found the percentage of PD in the high-risk group was higher than that in the low-risk group (Fig. 8E-F). Meanwhile, a significantly longer OS and PFS of patients in low-risk group than in high-risk group (Fig. 8G-H, p = 0.0039, p = 0.049).

Response of risk score to PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy in IMvigor210 cohort. (A) Risk score differences between immunotherapy response groups in the IMvigor210 cohort; (B) Immunotherapy response distribution among risk score groups in the IMvigor210 cohort; (C) OS differences among risk score groups in the IMvigor210 cohort; (D) PFS differences between risk score groups in the IMvigor210 cohort; (E-F) Distribution of immunotherapy responses among risk score groups in the GSE78220 cohort. (G) OS differences between risk score groups in advanced patients in the GSE78220; (H) PFS differences in risk score groups in the GSE78220 cohort. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001.

Development of a nomogram based on independent risk factors

Through univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis, we optimized the predictive performance of the risk signature. In multivariate analysis, risk signature was the most significant independent prognostic factor of NSCLC [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.258, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.981–5.357, P < 0.001], followed by N stage (HR = 1.922, 95% CI: 1.288–2.869, P = 0.001) (Fig. 9A-B). As shown in Fig. 9C, a nomogram combining stage and risk score was constructed. The calibration plot demonstrated that the nomogram can effectively forecast the actual survival outcomes, moreover, DCA revealed a better discriminative ability of the nomogram in recognizing patients at high risk than the risk score and stage, as shown in Fig. 9D. According to TimeROC analysis, the AUC for the risk score and nomogram was higher than that of other indicators in the TCGA cohort (Fig. 9E).

Development of a nomogram for predicting LUAD prognosis. (A-B) Multivariate (A) and univariate (B) Cox analyses of the risk score and clinicopathological characteristics; (C) Construction of a nomogram model that incorporates the risk score and stage; (D) Calibration curves for 1, 3, and 5 years of nomogram and decision curve for nomogram; (E) Time-ROC analysis was used to compare the predictive capacity of clinicopathological features and the nomogram. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Tumor cells and non-malignant cells such as immune cells and stromal cells are among the components of the TME. These cells influence tumor genesis, development, metastasis, and resistance to antitumor therapies, as well as establishing complex signals in the body20. Cancer cells often co-opt stromal cell functions to promote tumor progression and resistance to treatment. A similar treatment is administered to stromal cells in the microenvironment as it is to cancer cells. Some of the responses induced by these therapies may contribute to tumor progression, due to the damage induced by these therapies21. CAF cells play an important role in both primary and metastatic cancer progression through their interaction with other types of cells in the tumor microenvironment22. Based on scRNA-seq data, we performed a systematic characterization and classification of CAFs of LUAD to determine their diversity. CAF functional classification correlates with patients’ clinical response to targeted therapies and with the tumor immune microenvironment, providing an avenue to guide customized treatment9. Based on a score derived from DEGs across the five clusters, three clusters were consistently associated with LUAD prognosis. In an interesting finding, we observed HIPPO and RTK-RAS cluster differences among CAF clusters may play a role in CAF prognosis.

Based on the prognostic significance of the five CAF clusters, we developed a risk signature consisting of 8 genes centered on CAFs. It consisted of one protective gene (BTK) and three risk genes (CCNB1, CDC25C and EXO1). In our study, there were more SNV mutations in BTK, EXO1 and GRIA1, while none were observed in CCNB1, CLEC3B and METTL7A. Mutations in the Sense SNV influence the activity or functionality of proteins, which can contribute to the onset of HCC or impact its progression23. While independent studies have not established a direct connection between SNV mutations in these risk genes and the progression of LUAD, our findings also indicate that SNV mutations in these genes may play a significant role in the advancement of LUAD. Additionally, we discovered that the 8 genes showed significant associations with 41 pathways, with distinct pathway signatures evident between protective genes and risk genes. For example, the protective gene was significantly positively associated with antigen processing and presentation, apoptosis, B cell receptor signaling pathway, chemokine signaling pathway, et al., whereas risk genes were significantly connected with DNA replication, mismatch repair, p53 signaling pathway. The alterations of DNA replication play an important role in NSCLC and stress to promote chromosomal instability early in cancer evolution24. Mutations in the mismatch repair system predict the response to ICIs in NSCLC25. Therefore, this information guides us in investigating the regulation of these risk genes in LUAD further.

According to recent research, CAFs may promote tumor progression through their interaction with TMEs26. Through CAF-tumor interaction, Li et al. found that the HNRNPK/CLCN3 axis facilitates LUAD progression27. Given the prognostic values of three CAF clusters, we established a CAF-based risk signature with 8 genes. It consisted of one protective genes (BTK) and three risk genes (CCNB1, CDC25C and EXO1). There is potential cross-talk between these genes and TME in LUAD, and these genes could be therapeutic targets for LUAD. By interacting with these immune cells, CAFs can form an immunosuppressive TME, enabling tumor cells to evade immune surveillance28. CAF-based risk signatures were significantly correlated with stromal scores and immune cells, according to Yu et al. study14. In our study, SNV mutations were observed in CCNB1, CLEC3B and METTL7A without significant co-occurrence probability. A plot of SNV and CNV genes shows that LUAD high-risk individuals have obvious oncogene amplifications as well as tumor suppressor deletions, whereas LUAD low-risk individuals have both tumor suppressor deletions and tumor suppressor amplifications, along with a few oncogene amplifications29. CAF in LUAD primarily enhance the glutamine metabolism through a CAF-specific long noncoding RNA (LINC01614), which directly interacts with ANXA2 and p65 to facilitate the activation of NF-κB, leading to the upregulation of the glutamine transporters SLC38A2 and SLC7A5 and eventually enhances the glutamine influx of cancer cells10. In addition, we found that the 8 genes were significantly correlated with 41 pathways, while protective genes and risk genes showed clear differences in pathways. Therefore, these data provide us with a direction for further research on LUAD’s regulation of these risk genes.

Evidence suggests that tumor progression can be promoted by the interaction between CAFs and TMEs12. In our study, one predictive gene showed a significant positive correlation with immune score, while three risk genes showed a negative correlation. These data indicate that these genes may interact with TME in LUAD, suggesting they may be useful as therapeutic targets. A TME is comprised of several immune cells and determines the antitumor immune status synergistically14. It plays a critical role in tumorigenesis and immunosuppression in the TME when CAFs interact with immune cells that suppress the immune response30. In the risk signature, multiple types of T cells were negatively associated with the predictive genes. Based on the CAF signature, Ren et al. found that comprehensive characterization of LUAD can predict the response of LUAD to immunotherapy, and that EXP1 facilitates invasion and tumor cell growth31. Hence, CAF may play an important role in tumorigenesis and development, as well as regulating the microenvironment of tumors, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of nutritional immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy has shown clinically significant benefits for non-small-cell lung cancer, but innate (primary) and acquired resistance remain challenges32. As a result of our data, we were able to identify patients more likely to benefit from immunotherapies based on their risk signature. Also, POSTN + CAFs, which may cooperate with SPP1 + macrophages to promote the formation of desmoplastic architecture and suppress the immune system, and POSTN + CAFs associated with cancer progression and poor clinical outcomes, may provide new insights into NSCLC treatment33. A positive correlation was found between the risk genes and M0 macrophages, indicating that the risk genes play a role in macrophage polarization. Single-cell analysis reveals that COL11A1 + fibroblasts promote tumor progression by remodeling ECM and suppressing antitumor immune responses34. Additionally, we found that CAF-based signatures could predict response to anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. There data provided novel clues of the role of CAF in remodeling the cancer niche and immune status in TME. LUAD immunotherapy relies on CAF-TME communication, but further experiments are needed to clarify its role in LUAD.

In spite of this, there are a number of limitations in our study that should be acknowledged. In the first step, the CAF clusters and CAF-based risk signature were created from retrospective data extracted from public databases. Therefore, prospective LUAD cohorts and multicenter trials should be conducted in the future in order to validate the method. Second, the CAF-based risk signature was only investigated for its potential prognostic value, so further research is needed to determine the mechanisms involved in the development of LUAD.

Conclusion

As a result of this study, five distinct CAF clusters were identified in LUAD, each with distinct characteristics. The DEGs among the four clusters were enriched in cell-substrate adhension, collagen-containing extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix structural constituent and Focal adhesion signaling pathway, etc. A CAF-based prognostic risk signature with eight genes was constructed using three of the cluster’s significant associations with LUAD prognosis. PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy response could be predicted using CAF-based gene signatures connected to the immune landscape. Finally, we developed a novel nomogram that integrated risk signatures and clinicopathological features, resulting in improved prediction of the clinical outcome of LUAD patients.

Data availability

The NSCLC scRNA-seq datasets can be downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE149655. Due to survival analysis data can be downloaded from the following database GSE3141, GSE31210, GSE37745, GSE50081, GSE68465 and TCGA cohort. The original code in the study can be requested from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- LUAD:

-

Lung adenocarcinoma

- ICIs:

-

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors

- TME:

-

Tumor microenvironment

- CAFs:

-

Cancer associated fibroblasts

- ScRNA-seq :

-

ScRNA-seq Single-cell RNA-sequencing

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- UMI:

-

Unique Molecular Identifier

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- SNV:

-

Single-nucleotide variant

- CNV:

-

Copy number variant

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- ICB:

-

Immune checkpoint blocks

- CDC25C:

-

Cell division cycle 25 C

- EXO1:

-

Exonuclease 1

- CCNB1:

-

Cell cycle-related proteins cyclin B1

- DPYSL2:

-

Dihydropyrimidinase-like 2

- METTL7A:

-

Methyltransferase like 7 A

- CLEC3B:

-

C-Type Lectin Domain Family 3 Member B

- BTK:

-

Brutons tyrosine kinase

- GRIA:

-

Glutamate receptor

References

Srivastava, S. et al. Emerging role in prognosis, heterogeneity, and therapeutics. Sem. Cancer Biol. 86 (Pt 2), 233–246 (2022).

Desai, A. & Peters, S. Immunotherapy-based combinations in metastatic NSCLC. Cancer Treat. Rev. 116, 102545 (2023).

Otano, I., Ucero, A. C., Zugazagoitia, J. & Paz-Ares, L. At the crossroads of immunotherapy for oncogene-addicted subsets of NSCLC. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 20 (3), 143–159 (2023).

Song, X. et al. Spatial multi-omics revealed the impact of tumor ecosystem heterogeneity on immunotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with bispecific antibody. J. Immunother. Cancer ; 11(2). (2023).

Tiwari, A., Trivedi, R. & Lin, S. Y. Tumor microenvironment: barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J. Biomed. Sci. 29 (1), 83 (2022).

de Visser, K. E. & Joyce, J. A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: from cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer cell. 41 (3), 374–403 (2023).

Luo, H. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell analysis reveals the heterogeneity and plasticity of cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 6619 (2022).

Biffi, G. & Tuveson, D. A. Diversity and Biology of Cancer-Associated fibroblasts. Physiol. Rev. 101 (1), 147–176 (2021).

Hu, H. et al. Three subtypes of lung cancer fibroblasts define distinct therapeutic paradigms. Cancer cell. 39 (11), 1531–47e10 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-specific lncRNA LINC01614 enhances glutamine uptake in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 15 (1), 141 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Multi-scale integrative analyses identify THBS2(+) cancer-associated fibroblasts as a key orchestrator promoting aggressiveness in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Theranostics. 12 (7), 3104–3130 (2022).

Tang, P. C. et al. Smad3 Promotes Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Generation via Macrophage-Myofibroblast Transition. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany). ; 9(1):e2101235. (2022).

Sanchez-Vega, F. et al. Oncogenic signaling pathways in the Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell. 173 (2), 321–37e10 (2018).

Yu, L. et al. Characterization of cancer-related fibroblasts (CAF) in hepatocellular carcinoma and construction of CAF-based risk signature based on single-cell RNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data. Front. Immunol. 13, 1009789 (2022).

Xiang, H. et al. Single-cell analysis identifies NOTCH3-Mediated interactions between stromal cells that promote Microenvironment Remodeling and Invasion in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 84 (9), 1410–1425 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals a pro-invasive cancer-associated fibroblast subgroup associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with gastric cancer. Theranostics. 12 (2), 620–638 (2022).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51 (D1), D587–d92 (2023).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Science: Publication Protein Soc. 28 (11), 1947–1951 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression? Cell Death Dis. 14 (9), 587 (2023).

Berg, T. J. & Pietras, A. Radiotherapy-induced remodeling of the tumor microenvironment by stromal cells. Sem. Cancer Biol. 86 (Pt 3), 846–856 (2022).

Chen, Y., McAndrews, K. M. & Kalluri, R. Clinical and therapeutic relevance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 18 (12), 792–804 (2021).

Wang, H., Cao, H., Xu, Z., Wang, D. & Zeng, Y. SNP rs2596542G > A in MICA is associated with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Biosci. Rep.; 39(5). (2019).

Venkatesan, S. et al. Induction of APOBEC3 exacerbates DNA replication stress and chromosomal instability in early breast and Lung Cancer Evolution. Cancer Discov. 11 (10), 2456–2473 (2021).

Olivares-Hernández, A. et al. Influence of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system in survival and response to Immune Checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): retrospective analysis. Biomedicines; 10(2). (2022).

Barrett, R. L. & Puré, E. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and their influence on tumor immunity and immunotherapy. eLife; 9. (2020).

Li, Y. et al. HNRNPK/CLCN3 axis facilitates the progression of LUAD through CAF-tumor interaction. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18 (16), 6084–6101 (2022).

Mao, X. et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer. 20 (1), 131 (2021).

Zengin, T. & Önal-Süzek, T. Comprehensive profiling of genomic and transcriptomic differences between Risk Groups of Lung Adenocarcinoma and lung squamous cell carcinoma. J. Personalized Med.; 11(2). (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Integrative analyses of bulk and single-cell RNA-seq identified cancer-associated fibroblasts-related signature as a prognostic factor for immunotherapy in NSCLC. Cancer Immunol. Immunotherapy: CII. 72 (7), 2423–2442 (2023).

Ren, Q. et al. A novel signature predicts prognosis and immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma based on cancer-associated fibroblasts. Front. Immunol. 14, 1201573 (2023).

Frisone, D., Friedlaender, A., Addeo, A. & Tsantoulis, P. The Landscape of Immunotherapy Resistance in NSCLC. Front. Oncol. 12, 817548 (2022).

Chen, C. et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal POSTN(+) cancer-associated fibroblasts correlated with immune suppression and tumour progression in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Translational Med. 13 (12), e1515 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Single-cell analysis reveals the COL11A1(+) fibroblasts are cancer-specific fibroblasts that promote tumor progression. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1121586 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the Clinical research fund of Shandong Medical Association National (grant numbers YXH2022ZX02029), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81972796, 81972863).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SYJ and ZZH conducted statistical analyses of the data and prepared the draft manuscript. MXJ and ZKK edited the manuscript. All authors checked and proofread the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Si, Y., Zhao, Z., Meng, X. et al. RNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data analysis of cancer-related fibroblasts (CAF) in LUAD to construct a CAF-based risk signature. Sci Rep 14, 23243 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74336-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74336-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Single-cell RNA sequencing technology was employed to construct a risk prediction model for genes associated with pyroptosis and ferroptosis in lung adenocarcinoma

Respiratory Research (2025)

-

Fibrinogen beta chain as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in tobacco-associated lung adenocarcinoma

Discover Oncology (2025)

-

Identification of a fibroblast-derived gene signature reveals prognostic and therapeutic insights in pancreatic cancer

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2025)

-

Comprehensive analysis of a machine learning prognostic model for the interaction between mitochondrial function and lactylation in lung adenocarcinoma

Discover Oncology (2025)