Abstract

This research introduces an accelerated training approach for Vanilla Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) that addresses three factors affecting the loss function: the initial weight state of the neural network, the ratio of domain to boundary points, and the loss weighting factor. The proposed method involves two phases. In the initial phase, a unique loss function is created using a subset of boundary conditions and partial differential equation terms. Furthermore, we introduce preprocessing procedures that aim to decrease the variance during initialization and choose domain points according to the initial weight state of various neural networks. The second phase resembles Vanilla-PINN training, but a portion of the random weights are substituted with weights from the first phase. This implies that the neural network’s structure is designed to prioritize the boundary conditions, subsequently affecting the overall convergence. The study evaluates the method using three benchmarks: two-dimensional flow over a cylinder, an inverse problem of inlet velocity determination, and the Burger equation. Incorporating weights generated in the first training phase neutralizes imbalance effects. Notably, the proposed approach outperforms Vanilla-PINN in terms of speed, convergence likelihood and eliminates the need for hyperparameter tuning to balance the loss function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancements in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) have inspired researchers to explore new ways to integrate AI techniques into their respective fields. Raissi et al.’s pioneering work demonstrated the potential of neural networks as a powerful tool for solving partial differential equations (PDEs)1. The incorporation of a PDE loss term into the loss function, along with the mean squared error of predicting boundary conditions, led to the attainment of this solution. This breakthrough has since motivated many researchers to further investigate the use of deep learning techniques in various fields, including physics, finance, and engineering2,3,4. The vanilla form of PDEs solver, known as Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), represents a novel technique that has shifted attention from data-driven models to this emerging field5,6,7,8. The Vanilla PINN possesses notable versatility due to its mesh-free characteristics, enabling it to tackle a diverse range of challenges. It has proven its effectiveness in different scenarios, ranging from forward to inverse problems9. For instance, it has successfully addressed the lid-driven cavity test case, which is governed by the incompressible Navier-Stokes equation10. Additionally, it has demonstrated its ability in handling multiphase problems11, as well as scenarios involving flow past a cylinder and conjugate heat transfer12. These accomplishments solidify its status as a reliable approach for addressing various fluid mechanics challenges. However, the convergence issues and slow training time remain challenges.

As such, the pursuit to enhance the convergence speed of PINN has become a prominent research topic, marking the beginning of a new era in the field. An enhanced, yet more expensive approach to speeding up the convergence speed of PINNs is through the use of decomposition methods. One example of using this technique to speed up the convergence of PINNs is the work of Alena Kopaničáková et al. They employed a decomposed neural network strategy by dividing it into sub-networks, with each sub-network being trained separately on a dedicated GPU13. While techniques such as decomposition methods can lead to a faster convergence rate, they require expensive resources for solving PDEs. This poses a potential drawback, even for simple problems. However, there are other approaches that can accelerate convergence speed without the need for such resources. One such approach is transfer learning14. Transfer learning is a powerful approach that involves leveraging knowledge from a pre-trained model to enhance the learning of another model15. Although recent advancements in transfer learning techniques have demonstrated their potential in training deep learning models16,17,18, they are not widely applied to solve PDEs using neural networks. The fact that solutions to PDEs are specific to the problem being solved can make it difficult to effectively use transfer learning. The transferability of such tasks is considerably more challenging than that of classic tasks like image classification. Despite this difficulty, researchers have discovered novel applications of transfer learning for PINNs19,20,21. In addition to transfer learning, another technique that can help accelerate the convergence of neural networks is warm-up training. Warm-up training can help the model slowly adapt to the data and allows adaptive optimizers to compute correct statistics of the gradients22. Few studies have investigated the potential of warm-up training in this field23. Junjun Yan et al. utilized warm-up training to generate pseudo-labels, which were subsequently employed in the main training loop24. Another popular approach to warm-up training involves initial training for a defined number of iterations with the ADAM optimizer, followed by another training loop with LBFGS, which leads to faster convergence in comparison to vanilla PINN25.

Another field of study aimed at improving the convergence speed of vanilla PINN involves addressing the intrinsic problems with this method. As research in this area has progressed, new and improved methods have been developed that build upon the original vanilla form. These methods involve modifications to various components of the vanilla form, such as the architecture26, activation function27, training method28, sampling29, and loss function30. One of the challenges in PINN is dealing with an imbalanced loss function, where either the PDE loss term or the boundary condition loss term can dominate, depending on the problem context31. This issue can lead to a biased model that exhibits poor convergence. Lu et al. presented DeepXDE as a means to optimize the loss function of PINNs for PDEs. They proposed an approach called residual-based adaptive refinement (RAR), which incorporates supplementary collection points into areas characterized by high PDE residuals32. Nabian et al. introduced a collection point resampling strategy that utilizes importance sampling, relying on the loss function distribution to improve convergence33. Several studies have concentrated on addressing training issues through the use of adaptive sampling strategies34,35,36,37. These studies aim to optimize the training process by selecting strategically the most effective domain points at each stage of training. The primary objective of this approach is to maintain a balanced training procedure, which in turn, facilitates a more efficient convergence process. By ensuring a balanced distribution of domain points, these methods aim to optimize the learning process and improve the overall performance of the model. An alternative approach to selecting the optimal domain points at each training step involves the application of loss weighting strategies, which allow for direct control over the value of each term in the loss function. Wang et al. introduced a method known as ‘learning rate annealing for PINNS’ that dynamically adjusts the weights during the training process38. The fundamental principle of this method is the automatic adjustment of weights based on the statistics of the back-propagated gradient during model training, ensuring a balanced distribution across all elements of the loss function. This approach proved to be a more effective alternative to the previously employed method of manually adjusting the weights to balance the loss function39. In a different research study, Maddu et al. introduced a method that utilizes gradient variance to achieve a balanced training process for PINNs. This method, known as Inverse-Dirichlet Weighting, also incorporates a momentum update with a specific parameter. Experimental results indicate that this approach effectively mitigates the issue of gradient vanishing40. However, these methods, which use adaptive weighting schemes and dynamic updates for loss function balancing, may not be universally effective. The process of determining optimal weight values can be computationally intensive and potentially unsuccessful. The existing mentioned studies primarily concentrate on one factor to balance the loss function, neglecting other potential factors. These studies do not take into account all the elements that contribute to balancing the loss function. Furthermore, their proposed methods require calculation at every step of training, which makes them computationally intensive. This focus on a single aspect and the computational cost associated with their methods highlight the need for more comprehensive and efficient approaches.

In this study, we introduce additional factors that could cause an imbalance in the loss function for the first time. We propose an innovative training methodology that balances the loss function by taking all these factors into account. In the first phase of our proposed methodology, we introduce a novel loss function that is more efficient than other balancing strategies, as it thoroughly addresses all factors contributing to the balance of the loss function. We further enhance this phase by a new hypothesis that an initial weight state with lower variance is beneficial, and by using a new strategy for selecting the input space based on the Xavier initialization scheme.The second phase of our methodology is similar to the training of vanilla Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN). However, a key distinction lies in the utilization of the weights produced in the first phase. These weights are used to replace a proportion of the random weights in the neural network structure. In our methodology, the systematic replacement of weights not only balances the training process of the vanilla PINN for all factors but also offers a computational advantage as it is faster than traditional loss weighting strategies and adaptive methods. In this study, we employed three benchmarks to evaluate our methodology against the vanilla PINNs. Included benchmarks are as follows: a two-dimensional (2D) flow over a cylinder, an inverse problem to determining the inlet velocity in a 2D flow over a cylinder, and the Burgers’ equation. Notably, in Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”, we present the formulation of the vanilla PINN loss function as applied to the benchmarks under consideration, and we discuss the training challenges raised with this formulation in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”. In the subsequent sections, we introduce our alternative approach and conduct a comparative analysis with vanilla PINN.

Vanilla PINN loss function

In vanilla PINN, the loss function is defined by Eq. (1). The typical process for forming this loss function involves calculating derivatives based on the input for the first term while including all boundary conditions into the second term. Please note that in the studies mentioned earlier38,39,40, \(\:\lambda\:\) is used as the weighting factor in conjunction with adaptive strategies.

Navier-Stokes equations have been the primary choice for addressing laminar flow in the majority of research studies in this field41,42,43. Navier-Stokes equations are used to address the first two benchmarks. In these two benchmarks \(\:{L}_{pde}\) is a simplified version of the full Navier-Stokes equations under several assumptions: the flow is steady and two-dimensional (2D), the fluid is incompressible and Newtonian and the conservation of momentum is applied.

Where \(\:\rho\:\) represents the fluid density, \(\:u\) and \(\:v\) denote the \(\:x\) and \(\:y\) components of the velocity vector, \(\:\mu\:\) represents the dynamic viscosity, \(\:p\) corresponds to the fluid pressure, and \(\:\sigma\:\) denotes the stress. The loss function quantifies the difference between the predicted output of the neural network and the boundary value and uses PDE loss to understand the governing equation. In the first benchmark, the density of the fluid is 1 \(\:\frac{\text{k}\text{g}}{{\text{m}}^{3}}\:\)and the viscosity of the fluid is 0.02 \(\:\frac{\text{k}\text{g}}{\text{m}\text{s}}\) with an inlet Reynolds number of 26.6. The channel in this benchmark is characterized by a length of 1 m and a height of 0.4 m. Within this channel, the 2D cylinder has a diameter of 0.1 m. The positioning of the cylinder is such that it is located 0.15 m from the inlet and an equivalent distance from the bottom of the channel. The boundary condition applied to the wall of the channel is the no-slip condition, implying that the fluid velocity at the wall is zero. Furthermore, the pressure at the outlet of the channel is defined as zero. The velocity at the inlet is defined as follows:

The first benchmark is a forward problem where known boundary conditions are used to calculate velocity and pressure in the domain. On the other hand, the second benchmark poses an inverse problem. In this case, the inlet boundary condition is not included. Instead, the loss function utilizes 60 domain points with known velocity values. The final goal is to determine the inlet velocity.

Equation (11) quantifies the difference between the predicted output of the neural network and the boundary condition or the data available for the inverse problem. The formulation of this new loss term, which is central to the solution of the inverse problem, is defined as follows:

The final benchmark, referred to as Burger’s equation, is an unsteady problem with \(\:\mu\:=0.01\:\frac{kg}{m.sec}\) (Eq. (12)). In this benchmark, Burger’s equation is solved within a specific domain and time frame. The spatial variable, denoted as x, spans from 0 to 4 m. Concurrently, the time interval for the solution is defined from 0 to 5 s. The initial condition for this problem is derived by substituting \(\:u(x,t=0)\) into Eq. (13). The boundary conditions are defined such that the value of the output is zero when x equals either 0 or 4. With these settings in place, Burger’s equation can be solved to yield an exact solution which is Eq. (13).

\(\:{L}_{pde}\) for the last benchmark is formed by calculating the square of \(\:f0\) and averaging across the entire domain point. In conclusion, based on the PDE and the boundary conditions, the loss function for each benchmark is formed as follows:

Vanilla PINN training challenges

The loss function of vanilla PINN consists of two terms: the boundary loss and the PDE loss. The boundary loss measures how well the model matches the ground truth values of the boundary condition, while the PDE loss measures how well the model satisfies the derivative values that form the PDE equation. During training, the neural network’s weights are updated iteratively to minimize the loss function. This iterative update allows for the calculation of the desired outputs within the given domain. However, converging to a global minimum can be challenging because these two terms in the loss function have different scales and magnitudes. This difference makes the loss function imbalanced and difficult to optimize.

To investigate factors that lead to an imbalance in the vanilla PINN loss function, the first benchmark is utilized. Note that vanilla PINN in this case takes x and y as inputs and outputs u, v, p, \(\:{\sigma\:}_{xx}\), \(\:{\sigma\:}_{xy}\) and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{yy}\). Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) and random sampling methods are used to select domain points and boundary points, respectively. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the selected points. The density of selected points around the cylinder is higher than other parts of the domain to capture the underlying physics more accurately.

In this test case, we observed that a minor adjustment in the ratio of the number of domain points to boundary points, from 0.035 in Case 1 to 0.033 in Case 2, led to a change in the optimal value of \(\:\lambda\:\). To quantify this impact, we trained the vanilla PINN for different values of \(\:\lambda\:\) for each case and reported the average training time in Table 1. The reason for reporting the average training time is that the convergence of the neural network is significantly influenced by its initial state. A more detailed explanation of this effect is provided in Section “Results and discussion” of this paper. The data in Table 1 illustrates how different ratios can influence the optimal value of \(\:\lambda\:\). A minor adjustment in the ratio of the number of domain points to boundary points can result in a significant change in training time or even cause divergence. For instance, when \(\:\lambda\:\) is 0.5, the average training time is considerably faster in Case 2 compared to Case (1) Conversely, the training time for \(\:\lambda\:\) =1 is faster in Case 1 than in Case (2) The training process is halted when the loss value reaches a threshold of 10− 3. This observation underscores the sensitivity of the training process to the initial conditions, domain to boundary points, and \(\:\lambda\:\) value.

From Table 1, three factors can be identified that potentially cause the loss function to be imbalanced.

-

1.

The first cause is related to the initial weights state of the neural network. This is a random factor and cannot be controlled or predicted, which is why the average training time is reported in Table 1. The randomness of the initial weights can lead to different learning paths during the training process, and consequently, to different local minima in the loss function. As a result, both the training time and the likelihood of convergence can vary across different runs, even when the same hyperparameters are used.

-

2.

As indicated in Table 1, the ratio of domain points to boundary points is a crucial factor that can result in an imbalance within the loss function. This imbalance occurs because the number of domain points can fluctuate depending on various scenarios, leading to the dominance of either the PDE loss or the boundary condition loss31.

-

3.

The final factor, as outlined in Table 1, is the \(\:\lambda\:\) value. This factor is particularly beneficial for researchers as it can be directly set in the loss function. The \(\:\lambda\:\) value directly controls the average value of the boundary condition loss term in the loss function. However, it is important to note that the incorrect selection of this hyperparameter can exacerbate the imbalance in the loss function.

While the tuning of the \(\:\lambda\:\) value can be beneficial in optimizing the loss function, it can become more challenging when a lower threshold for total loss value, such as 10− 4, is set as a threshold to stop the training. As a result, the process becomes even more challenging and time-consuming, with an increased risk that the loss function may not converge to the desired threshold. Figure 2 illustrates how the different \(\:\lambda\:\) values can affect the time of convergence and whether convergence is possible for the set threshold. In the majority of existing research38,39,40, the primary emphasis is placed on the third factor, often overlooking the simultaneous influence of all three factors. For instance, the initial weight state, a factor that has not been previously addressed, exhibits a complex relationship with the \(\:\lambda\:\) factor. The intricate interplay among the initial weights state, the \(\:\lambda\:\) value, and the ratio of domain to boundary points are clearly demonstrated in Table 2 of this study. For a fixed \(\:\lambda\:\) value and domain to boundary points ratio, it is observed in this table that only a few initial weight states lead to convergence for the Vanilla PINN. It is important to note that a more in-depth exploration of the factors contributing to the imbalance in the loss function is conducted in Table 2 of this paper, following the proposition of a comprehensive solution.

Methodology

As outlined in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”, imbalanced loss function can complicate the training process. We propose that incorporating weights and biases, which are trained to learn boundary conditions, into the neural network can balance the loss function during training. This proposition is based on the assumption that such initialization could steer the network toward solutions that align with the subset of boundary conditions. The logic behind this is that if a proportion of weights and biases of a neural network is capable of predicting the boundary conditions, then this proportion will influence the network’s predictions. This suggests that the structure of the neural network is designed to favor the boundary conditions, which in turn influences the overall convergence of the loss function. This implies that, due to the omission of some boundary conditions in the loss function, the solution learned by the neural network is not unique and differs from the exact solution. Consequently, the boundary it learns is aligned with the boundary conditions of the main problem. However, the solution learned within the domain does not match the exact solution.

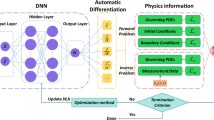

In this study, our approach is named ‘Feature-Enforcing-PINN’ for clarity, and the term ‘smart weights’ is used for weights and biases informed by boundary conditions. The process of incorporating smart weights into the neural network is termed ‘smart initialization’. Our research methodology’s contributions are organized as follows: In Section “Loss function for the smart weights”, we introduce the Primary Loss Function. This novel loss function is specifically designed to guide the neural network to learn only a subset of the boundary conditions, rather than the exact solution of the PDE. Following this, in Section “Reducing variance”, we discuss the crucial role of variance reduction prior to training the neural network in our approach. This step is essential to ensure the stability and efficiency of the learning process of FE-PINN. In Section “Progressive neural network training: from trivial to exactsolutions”, we present our new strategy for selecting domain points. Training the neural network with the Primary Loss Function and the aforementioned preprocessing steps results in what we refer to as ‘smart weights’. Subsequently, we augment the network structure by adding extra layers with random weights. Finally, the enhanced neural network is trained on the complete loss function. This comprehensive novel approach ensures that our neural network’s loss function is balanced and remains unaffected by the three primary causes discussed in Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”, which typically render the vanilla PINN loss function imbalanced. Finally, in Section “Results and discussion”, we conduct a comparative analysis between our proposed methodology, which we refer to as FE-PINN, and Vanilla PINN.

Loss function for the smart weights

In the process of solving PDEs, the absence of the necessary boundary conditions often leads to non-unique solutions, thereby opening up a range of potential answers. Drawing from this analogy, we have devised a loss function, referred to as the Primary Loss Function, to find one of the non-unique solutions. Training a neural network with this loss function results in a set of parameters, which we termed smart weights in Section “Methodology”. Note that smart weights are used to replace a proportion of random weights in the structure of a neural network in the training process of Vanilla PINN. The Primary Loss Function is defined as follows for each benchmark:

Different forms of the Primary Loss Function can influence both phases of the training process. Increasing the number of conditions in this loss function tends to extend the training time in the first phase, although it may not always yield additional benefits in the second phase. Therefore, the number of terms in the loss function should be carefully tuned based on the specific design requirements. Initially, it is recommended to exclude at least one boundary condition, ideally one from each dimension. Additionally, removing obstacles such as cylinders can help avoid complications. Incorporating data from the inverse problem is also beneficial, as it positively impacts the training process.

Please note that the loss function defined in this section is solely for the creation of smart weights, which is distinct from the vanilla PINN loss function outlined in Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”. The notable distinction in training time between smart initialization and the main training loop arises from the existence of multiple valid solutions for the primary loss function, which aids the neural network in identifying a global minimum. Moreover, the application of variance reduction techniques, as discussed in Section “Loss function for the smart weights”, significantly reduces the initial loss, providing a more favorable starting point. Additionally, the reduction in the number of PDE points further enhances convergence speed, thereby optimizing the training process.

Reducing variance

During the training process, smart weights can lose their information about the primary loss function after a few iterations. This occurs because both types of weights have similar update rates due to their comparable gradients and identical learning rates. As a result, the training process becomes imbalanced, resembling the behavior of a vanilla PINN, as discussed in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”.

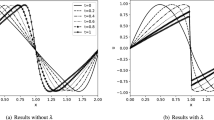

To prevent smart weights from losing their information, a novel initialization approach is employed before the first phase of training, wherein random weights are initialized with a lower variance, resulting in smaller initial gradients. After reducing variance and training the neural network with the Primary Loss Function, the newly created smart weights replace a portion of the random weights within the structure of the neural network. These random weights, initialized using the Xavier method, exhibit a higher variance and larger gradients, causing them to update more rapidly during training on the complete loss function from Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”. Since smart weights are predominantly identical and possess smaller gradients, they undergo minimal changes during training on the vanilla PINN loss function. This strategy ensures that the smart weights maintain their boundary condition knowledge for more iterations due to their lower variance, smaller gradients, and consistent response to input. To illustrate the influence of variance reduction on the gradient and \(\:{L}_{pde}\) before training, Table 3; Fig. 3 are presented. Figure 3 compares the outputs and their derivatives with respect to inputs after and before reducing initialization variance. For instance, in the first benchmark, output values (u, v, p) after reducing variance are near zero and exhibit minimal changes, while those before this process vary more significantly as illustrated in Fig. 3a, b. Additionally, derivative values after reducing variance are much smaller, indicating smoother variation across the domain as shown in Fig. 3c, d. This observation is confirmed by repeating the process with different random seeds. Table 3 presents the \(\:{L}_{pde}\) for both networks, showing that the network with lower variance assigns a lower PDE loss value due to its smaller derivative values. This pattern holds across different random seeds and domain points, suggesting that the procedure is systematic rather than random. The initial lower loss value of \(\:{L}_{pde}\) helps the neural network start the training process in a better initial state, which makes convergence faster. Note that this process is specifically designed for this stage based on the multiple valid answers of this phase and is not a useful strategy in the next stage. Furthermore, if this factor is low, it causes divergence, while if it is near one, it doesn’t impact the training. Based on the empirical data of our study, we suggest using a factor between 1/√5 and 1/√10. Please note that this recommendation is derived from the three benchmarks discussed in this study. Adjusting this factor may prove beneficial for new benchmarks.

The first set of three figures, labeled as (b), illustrates the variables (u, v, p) for the neural network post-variance reduction. In contrast, figures labeled as (a) represent the neural network initialized using the Xavier scheme. The final set of three figures exhibits the value of du/dx for two scenarios: one for the neural network after variance reduction (d), and the other for a neural network initialized using the Xavier scheme(c). Please note that all the figures presented are post-variance reduction and prior to the commencement of any training.

Progressive neural network training: from trivial to exact solutions

An alternative strategy for LHS involves the computation of PDE residuals at each iteration of training the neural network. If these residuals exceed a predetermined threshold for domain points, they are chosen as input points for that iteration. This iterative method, introduced by Arka Daw et al., is feasible because PDE residuals are a function of a neural network’s weight state44.

The Xavier initialization method, when applied with different random seeds, results in different weight configurations for a neural network. As the loss function is dependent on the weight state, this leads to diverse outcomes when calculating the PDE residual for domain points. Utilizing different random seeds and selecting domain points that surpass a specific PDE residual threshold result in a unique set of domain points for each initial weight state. Consequently, with each change in the random seed, the focus shifts to a different part of the domain, from which the domain points are then selected. This results in a higher density of points in that area compared to the rest of the domain. This non-uniform distribution leads to the exclusion of certain parts of the domain from the selection of domain points. This exclusion allows the neural network to focus on its interpolation capabilities within the excluded areas. To clarify, the process we utilize for the selection of domain points is designed with an emphasis on using interpolation across the excluded parts of the domain. In other words, rather than learning the exact solution, the network is trained to make predictions within certain boundaries. This is due to the presence of only a subset of boundary conditions in the Primary Loss Function. This procedure, which employs N different random seeds to select domain points, is executed before the training process begins. This strategy for domain point selection is a modification of the method introduced by Arka Daw. Note that N is a hyperparameter that determines the number of different random seeds used for initializing the neural network’s weights. The choice of N can influence the diversity of the domain points selected during training. However, for a wide range of values, the outcome remains consistent, indicating that the exact value of N is not critical to the strategy’s success. Empirical observations suggest that using between 5 and 10 random seeds yields similar results.

This approach is used to select domain points for all the benchmarks in the first training phase, with the number of domain points directly influencing the computational complexity. By using domain point selection based on the initial weight state as a criterion, the approach aims to reduce domain points for generating smart weights in the smart initialization phase. We train a neural network on the Primary Loss Function for each benchmark using the selected domain points. This training occurs after the preprocessing step outlined in Section “Reducing variance”. All benchmarks are trained exclusively using a GPU RTX 4080. Following the initial training phase, smart weights are produced. Upon the generation of smart weights for each benchmark, these weights are subsequently utilized to substitute a proportion of the weights within a neural network, which was initialized via the Xavier initialization method. In the training process of a neural network, we strategically replace the weights in both the output layer and the initial few layers with smart weights. This replacement ensures that these critical layers have a more pronounced impact on the learning process and the overall performance of the network. It’s important to note in a neural network these layers have distinct roles. The output layer, for instance, is crucial as it is directly responsible for the final prediction made by the neural network. Conversely, the initial layers are typically tasked with learning the basic features of the input data, serving as the foundation for the subsequent layers. This strategic weight replacement enhances convergence and balances the training for the second phase. After the addition of smart weights, the second training process is carried out on the loss function, defined in Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”. Unlike the first training phase, the LHS method is used to select domain points for this phase. Figure 4 depicts the structure of the neural network for the first two benchmarks. In this figure, the smart weights, which are obtained after training on the Primary Loss Function, are represented by blue lines. Conversely, the red lines illustrate the random weights that were added using Xavier initialization. It is imperative to acknowledge that the initial two benchmarks utilize ‘x’ and ‘y’ as inputs, whereas the final benchmark employs ‘x’ and ‘time’. The neural network for the first two benchmarks comprises eight hidden layers, each encompassing 40 neurons. The weights of half of these hidden layers, precisely four, are substituted with smart weights. Conversely, the neural network for the final benchmark consists of four hidden layers, with the weights of half of these layers, precisely two, being replaced with smart weights. It is noteworthy that the increased complexity of the first two benchmarks, in comparison to the last one, necessitates a greater number of hidden layers in these two benchmarks.

Results and discussion

First benchmark

In the initial training process, the ADAM optimizer with a learning rate of 3 × 10−4 is used, focusing on \(\:{PL}_{{Benchmark}_{1}}\) with an average training time of 1.2 min. This enables the network to predict (u), (v), and (p) values for the primary loss function of the first benchmark, as shown in Fig. 5. Note that this figure shows one possible solution where the network learns specific terms in the primary loss function and one of the non-unique solutions of the PDE due to the absence of some boundaries.

Upon the creation of smart weights and the enhancement of the network’s complexity by appending additional layers atop them before the output layer, the subsequent step entails training the newly established model by utilizing the complete loss function represented by \(\:{L}_{{Benchmark}_{1}}\). In the second training process, the parameter \(\:\lambda\:\) is kept at 1 for the entire training process for FE-PINN while tuned for vanilla PINN. Domain points are selected by utilizing the LHS method, as depicted in Fig. 1. The optimization process employs the LBFGS method from the Torch library.

In our investigation of balancing factors outlined in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”, we refer to Table 2. It’s crucial to note that the initial weight state of both the vanilla PINN and FE-PINN share the same weights in the red layers of Fig. 4 for each row of Table 2. The key difference lies in the blue layers, which are created using a smart initialization process for FE-PINN, while Xavier initialization is used for the vanilla PINN. Smart weights as blue layers for our model make the loss function balanced while random weights as blue layers make the vanilla PINN loss function imbalanced. The time required for smart initialization is detailed in the second column of Table 2, represented by the first number before the addition sign, and the second number is the training time of FE-PINN. In order to address the second cause mentioned in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”., we report the time required for convergence, considering various ratios of domain to boundary points. Each ratio is reported three times to account for the potential influence of the initial weight state on the convergence process which is the first cause. For instance, at a ratio of 41.7, FE-PINN converges to the desired threshold, which is 10− 4, but the vanilla PINN cannot converge in two of the three cases for \(\:\lambda\:=1\). The reasons behind the failure of the vanilla PINN to converge are the first two causes mentioned earlier. However, in certain cases, such as ratios of 43.81 and 20.72, the vanilla PINN fails to converge to the desired threshold with three different initial weight states for \(\:\lambda\:=1\). This suggests that the imbalance is caused by the ratio of domain points to boundary points in these instances. In contrast, FE-PINN ensures that the loss function remains balanced across different ratios and converges in all cases of Table 2. Also, in some ratios where the initial weight state causes the vanilla PINN to fail to converge, FE-PINN still converges. For instance, in the first case of ratio 20.72 with the same initial weight state in the red layers (Fig. 4) for both models, FE-PINN converges in 22.7 min while the vanilla PINN fails to converge. In the second case, when the vanilla PINN manages to converge with a \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1.2, our model still converges two times faster. It’s important to note that in all cases where vanilla PINN converges, not only does our model converge, but it also converges faster than the vanilla PINN. Tables 2 and 4 demonstrate the fact that the loss function is balanced for all three causes mentioned in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”, highlighting a key feature of FE-PINN and its robust performance across various scenarios. Taking into account the impact of the \(\:\lambda\:\) value on the convergence of vanilla PINN, the training times for \(\:\lambda\:\) values of 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, and 1.8 are reported in Table 2. For this benchmark, it is observed that the likelihood of non-convergence is higher for a \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1 compared to other \(\:\lambda\:\) values. Interestingly, the \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1.2 emerges as the most successful, achieving convergence 72% of the time. Upon calculating the average time required for convergence at a \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1.2, it is found to be approximately 49.4 min. In contrast, the average training time for the FE-PINN is about 24.3 min, which is more than twice as fast as the vanilla PINN. Also, it’s important to note that FE-PINN converges in all cases across all three benchmarks. This demonstrates that there is no need to tune the \(\:\lambda\:\) value, find the optimum ratio of domain points to boundary points, and that the convergence of FE-PINN is independent of initial states. This is why the training time for FE-PINN is reported only at a \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1.

Table 2 reveals that for \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1, the vanilla PINN only converges 33% of the time, underscoring the necessity for hyperparameter tuning. The smart initialization introduced in this study can replace the time-consuming process of \(\:\lambda\:\) tuning. As shown in Table 4, on average, the smart initialization and training times in FE-PINN are faster compared to the hyperparameter tuning and training times of the vanilla PINN, respectively. We employ a random search to quantify the average time required to find the optimal \(\:\lambda\:\) value for the vanilla PINN. This process is repeated five times to ensure the total time is independent of randomness. For each iteration, the tuning time and the convergence time of the best \(\:\lambda\:\) value are measured. The average times are then calculated and reported in Table 4. On average, the smart initialization process in FE-PINN is 144 times faster when using the \(\:{PL}_{{Benchmark}_{1}}\) instead of tuning \(\:\lambda\:\) directly. This demonstrates that our approach not only eliminates the need for hyperparameter tuning but also trains faster on the target task. The Big O notation is utilized to characterize the growth rate of the number of operations, disregarding constant factors and lower-order terms. The Big O (time complexity) of training a vanilla PINN is dependent on various factors such as the total number of layers, the total number of neurons per layer, the number of input and output features, the number of domain points, the number of epochs, calculated derivatives, the optimization algorithm, and the tuning of the \(\:\lambda\:\) value. Note that in Table 4, both FE-PINN and the vanilla PINN share identical characteristics, with one distinction: the \(\:\lambda\:\) value in the vanilla PINN necessitates tuning, but our approach replaces this process with a low-cost, smart initialization process. The difference between the Big O notation for FE-PINN and the vanilla PINN lies in the necessity to explore the optimal value for \(\:\lambda\:\) in the loss function of the vanilla PINN. For the vanilla PINN, in the best-case scenario, the first selected \(\:\lambda\:\) value converges to the desired threshold (O(1)), while in the worst-case scenario, all possible values must be explored (O(n)), where n is the number of iterations performed to find the best value of \(\:\lambda\:\). However, in the case of our approach, there is no need for such a process. Instead, a low-cost smart initialization can replace the exploration of different \(\:\lambda\:\) values, with an average training time of just one minute. It is important to note that for the FE-PINN, the time complexity is O(1), which means it is constant and does not depend on finding the optimum \(\:\lambda\:\) value.

Figure 6 provides a clear illustration of how the loss function of FE-PINN achieves its global minimum more efficiently compared to PINN. This example corresponds to Table 2 for the ratio 41.7, case 1. The blue line represents FE-PINN, while the other line represents PINN with a lambda value of 1.8. The red line indicates the stopping criteria. This figure demonstrates that significantly fewer epochs are required to train FE-PINN.

Although the computational cost for the forward and backward phases of each epoch is equivalent for both PINN and FE-PINN due to our design, the overall computational cost of FE-PINN is lower. This reduction is attributed to FE-PINN requiring fewer epochs to converge to the desired threshold, achieved through the implementation of smart weights, resulting in a lower total number of operations.

In Fig. 7, the outputs of our methodology and the vanilla PINN are compared visually. Note the difference between Figs. 5 and 7. Figure 5 is the prediction of our model after the first training phase while Fig. 7 is the result of the second training phase. Finally, the FE-PINN predictions are validated using simulation results, keeping the ‘y’ constant for velocity magnitude in Fig. 8.

Second benchmark

Vanilla PINN has shown potential in addressing inverse problems, which are inherently ill-posed due to the presence of unknown boundary conditions. In this section, we present a comparative analysis of the performance of FE-PINN and the vanilla PINN in resolving an inverse problem characterized in Section “Vanilla PINN loss function”. Benchmark 2 is depicted in Fig. 9. Furthermore, we have 60 domain points with known u and v values, as denoted by the blue marks in Fig. 9. As previously described, the neural network is initially trained on the \(\:{PL}_{{Benchmark}_{2}}\) using Adam optimizer. Following the smart initialization process introduced in this study, the model is then trained on \(\:{L}_{{Benchmark}_{2}}\) to solve the problem.

In order to ensure a fair comparison, both FE-PINN and the vanilla PINN are trained under comparable conditions. This includes employing the same learning rate, the same optimization algorithm (LBFGS), an identical number of domain and boundary points, and a similar structure. It is important to note that the structure of both the vanilla PINN and our approach remains consistent with the previous section, encompassing the same number of layers, inputs, and neurons. The training phase for both methods is terminated when the loss value reaches a threshold of 10− 4. Table 5 provides a comparison of the average training time of FE-PINN and the vanilla PINN. In this benchmark, akin to the previous one, three distinct initial states are considered for each ratio, with varying \(\:\lambda\:\) values. This approach is designed to account for the three factors contributing to the imbalance of the loss function, as detailed in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”. Empirical data from Table 5 suggests that the FE-PINN consistently converges faster than the Vanilla PINN across all cases. However, it is noteworthy that the Vanilla PINN fails to converge in some instances, underscoring the superior reliability and efficiency of the FE-PINN method in these scenarios. In order to quantify the effectiveness of FE-PINN across various causes of imbalance, the training time and smart initialization time of FE-PINN are averaged across all 18 cases presented in Table 5. A similar averaging process is employed for Vanilla PINN across different \(\:\lambda\:\) values. The results suggest that the average total training time for FE-PINN is 13.4 min in all 18 cases in Table 5. In contrast, the average total training times for Vanilla PINN are 25.7, 21.8, 22.7, 23.6, and 23.5 min respectively for each \(\:\lambda\:\) value ranging from 1 to 1.8. Another crucial observation is that, across various ratios, only at the ratio of 43.25 does the Vanilla PINN successfully converge to the fixed threshold in all instances while FE-PINN converges in all cases. The final cause of imbalance, which is the initial state of the neural network, also plays a crucial role. For instance, in Case 3 of ratio 21.47, the Vanilla PINN could not converge for different \(\:\lambda\:\) values due to its initial weight state, while the FE-PINN converged in approximately 15 min. It’s also important to note that to account for the effect of the initial state, like all the benchmarks, in each row of Table 5, the initial weights of FE-PINN and Vanilla PINN are exactly the same. The only difference is that the blue layers in Fig. 4 are replaced with smart weights for FE-PINN. This approach ensures a fair comparison while highlighting the effectiveness of smart weights in FE-PINN. As demonstrated in Tables 2 and 5, the relationship between the initial weight state, the ratio of the domain to boundary points, and the \(\:\lambda\:\) value on the convergence of Vanilla PINN is a complex interplay. Often, more than one factor influences the convergence process, suggesting the intricacy of identifying the optimal state for each of these three factors. Finding the optimum state can be challenging prior to the training process and typically necessitates a trial-and-error approach. However, the smart initialization process of FE-PINN eliminates this trial-and-error process. This is a key feature of our approach, in addition to its faster convergence speed, underscoring the efficiency and effectiveness of FE-PINN in handling these complexities. As a final note, the validation of this benchmark is conducted using the R-squared metric to compare the effectiveness of these models in predicting the inlet velocity. It was observed that for all cases that reach the threshold of 0.0001, the R-squared value is greater than or equal to 0.999. This high R-squared value suggests a strong correlation between the predicted and actual values, indicating the high accuracy of the models in predicting the inlet velocity.

Third benchmark

The final benchmark under consideration necessitates fewer derivatives to be computed and has fewer boundary conditions compared to the first two benchmarks. The decrease in terms within the loss function results in a more balanced loss function relative to the first benchmark. Consequently, the loss function is less influenced by the three primary sources of imbalance, as outlined in Section “Vanilla PINN training challenges”. The empirical evidence supporting this claim is clearly shown in the results presented in Tables 2 and 5, and 6.

To investigate the influence of the initialization with random weights, the ratio of the domain to boundary points, and \(\:\lambda\:\) value on the balance of the loss function for this benchmark, we refer to Table 6. In the given table, each row, such as the one represented by Table 2, maintains the same random weights across all models in each row. However, there is a distinct difference when it comes to the first hidden layer and the output layer for the ‘FE-PINN’ column. Random weights in these layers are replaced by smart weights. Note that for every ratio, each of the three cases uses a unique random seed. This accounts for the influence of the initial weight state on the results. In the third column of the table, the first number indicates the outcome of the smart initialization process. This process involves training the neural network on the \(\:{PL}_{{Benchmark}_{3}}\). The second number, which follows the addition sign, represents the training time. All times for this benchmark are reported in seconds. The training process is designed to stop once the total loss value reaches a threshold of 1 × 10− 6. When this threshold is reached, the neural network is able to accurately predict the solution, as illustrated in Fig. 10. Upon closer examination of Table 6, it becomes apparent that our proposed method exhibits a faster convergence rate compared to the vanilla PINN across all considered ratios in each case. For the vanilla PINN to achieve a training time comparable to our method, the three main factors that influence the loss function must be in their optimal states. For instance, in Case 3, where the ratio is 11.25, all three factors are near their optimal states for the vanilla PINN with a \(\:\lambda\:\) value of 1. Consequently, the training time of the vanilla PINN is comparable to the sum of our approach’s training time and its smart initialization process in this case. In contrast, in case 1 from the previous ratio, the only altered factor is a new random weight state. Note that in this case, the training time is different from case 3 as expected since the randomness of the initial weights can lead to different learning paths during the training process. However, in this case, FE-PINN converges 1.5 times faster than the vanilla PINN. This suggests that, despite the change in random weights, the loss function remains balanced due to the presence of smart weights for FE-PINN. However, in the case of vanilla PINN, this change in random weights results in a more imbalanced loss function, which is the reason for its longer training time compared to FE-PINN. It is important to note that finding an initial state that results in a balanced loss function is nearly impossible in the vanilla PINN as it is entirely dependent on randomness. In our approach, the smart weights neutralize the effect of the initial state on the loss function. This demonstrates the robustness of our approach in maintaining balance and achieving faster convergence, regardless of the randomness introduced by different seeds. Furthermore, FE-PINN consistently outperforms the vanilla PINN across all ratios, indicating that its loss function is highly balanced and less affected by different causes. Notably, this balance is maintained across an extensive range of ratios, demonstrating the method’s adaptability and robustness. This characteristic is particularly significant as it negates the necessity to identify an optimum ratio for convergence. Lastly, while the \(\:\lambda\:\) factor can be tuned for the vanilla PINN to match the convergence speed of our approach, this process is time-consuming compared to the process of smart initialization, which in this case took only about 5 s. This is significantly faster when compared to the time-consuming task of tuning the \(\:\lambda\:\) factor for this benchmark. Therefore, our approach not only addresses all causes that make loss function imbalance but also reduces the training time. It’s important to highlight that the last benchmark is less complex than the initial one. Consequently, it has a higher probability of converging to the desired threshold, primarily due to a more balanced loss function. Our methodology demonstrates efficacy even in the context of simpler benchmarks. However, the effectiveness of our approach becomes more evident when tackling more complex problems where the loss function is significantly influenced by imbalances, as observed in the first benchmark.

Conclusion

This study tackles the convergence issues of the Vanilla Physics Informed Neural Network (PINN), a method for solving partial differential equations (PDEs). The main issue with the Vanilla PINN is its struggle to converge due to an imbalanced loss function. We identified three main factors contributing to this imbalance: the initial weight state of a neural network, the ratio of the domain to boundary points, and the loss weighting factor. To tackle these challenges, We propose a process termed as Feature-Enforcing PINN (FE-PINN). This is a progressive approach to neural network training that transitions from trivial to exact solutions. First, we introduce a novel loss function and a new preprocessing step including reducing initialization variance, and domain point selection based on different initial neural network states, producing “smart weights”. Finally, to transition from a trivial solution to the exact solution, a proportion of random weights are replaced by smart weights. Subsequently, the rest of the training is carried out in a manner similar to vanilla PINN. Three benchmarks were used to compare our approach with the Vanilla PINN. Our findings indicate that our approach converges faster than the Vanilla PINN, even when hyperparameter tuning is employed to balance the loss function. In contrast to the Vanilla PINN, the smart weights in our study neutralize the effects of the three aforementioned factors on the loss function. Our approach performs best in more complex problems, which have more boundary conditions and derivatives. In these scenarios, the Vanilla PINN fails to converge and needs to find an optimum state for the imbalance factors. However, our approach is not affected by these factors. Even in simpler problems, our approach is still faster than the Vanilla PINN. It is noteworthy that the initial phase of our training methodology exhibits superior efficiency and speed compared to the process of determining the optimal ratio and loss weighting strategies. For instance, in the first benchmark, the initial phase of training was completed in approximately one minute, which is 144 times faster than the loss weighting process in a Vanilla PINN. The approach introduced in this study effectively balances the loss function for various factors, while maintaining a faster speed. This makes it robust and suitable for a wide range of applications. Ultimately, since the second phase of FE-PINN mirrors vanilla PINN, employing methods like adaptive activation functions and adaptive sampling can potentially yield better results and warrants further investigation. Additionally, other approaches such as varying learning rates for different layers of the network, instead of focusing solely on variance reduction, can also be explored. These strategies may enhance the performance and efficiency of the FE-PINN framework, making it a promising area for future research.

Data availability

The data files and scripts used in this research are publicly available in the GitHub repository https://github.com/mahyar-jahaninasab/Feature-Enforcing-PINN.

References

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Meinders, M. B. J., Yang, J. & van der Linden, E. Application of physics encoded neural networks to improve predictability of properties of complex multi-scale systems. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1–12 (2024).

Zhu, Q., Liu, Z. & Yan, J. Machine learning for metal additive manufacturing: Predicting temperature and melt pool fluid dynamics using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Mech. 67, 619–635 (2021).

Leon, C. Physics-constrained machine learning for electrodynamics without gauge ambiguity based on Fourier transformed Maxwell’s equations. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 14809 (2024).

Kim, S., Cho, M. & Sungjune Jung. The design of an inkjet drive waveform using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 4841 (2022).

Jahaninasab, M., Taheran, E., Alireza Zarabadi, S., Aghaei, M. & Rajabpour, A. A novel approach for reducing feature space dimensionality and developing a universal machine learning model for coated tubes in cross-flow heat exchangers Energies 16(13), 5185 (2023).

Aslam, M. et al. Machine learning intelligent based hydromagnetic thermal transport under Soret and Dufour effects in convergent/divergent channels: A hybrid evolutionary numerical algorithm. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 21973 (2023).

Liu, Y., Zou, Z., Pak, O. S., Alan, C. H. & Tsang. Learning to cooperate for low-Reynolds-number swimming: A model problem for gait coordination. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 9397 (2023).

Liu, W., Kam, G., Karniadakis, S., Tang & Yvonnet, J. A computational mechanics special issue on: Data-driven modeling and simulation—theory, methods, and applications. Comput. Mech. 64, 275–277 (2019).

Boullé, N., Earls, C. J. & Townsend, A. Data-driven discovery of Green’s functions with human-understandable deep learning. Sci. Rep, 12(1), 4824 (2022).

Amini, D., Haghighat, E. & Juanes, R. Inverse modeling of nonisothermal multiphase poromechanics using physics-informed neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 490, 112323 (2023).

Cai, S., Wang, Z., Wang, S., Perdikaris, P. & Em Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks for heat transfer problems. J. Heat Transfer 143(6), 060801 (2021).

Kopaničáková, A., Kothari, H., Karniadakis, G. E. & Krause, R. Enhancing training of physics-informed neural networks using domain-decomposition based preconditioning strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17648 (2023).

Lyu, Y., Zhao, X., Gong, Z., Kang, X. & Yao, W. Multi-fidelity prediction of fluid flow based on transfer learning using Fourier neural operator. Phys. Fluids 35, 7 (2023).

Ying, Wei, Y., Zhang, J., Huang & Yang, Q. Transfer learning via learning to transfer. In International Conference on Machine Learning 5085–5094 (PMLR, 2018).

Cao, B., Pan, S. J., Zhang, Y., Yeung, D. Y. & Yang, Q. Adaptive transfer learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 24(1), 407–412 (2010).

Shi, N., Zeng, Q. & Lee, R. Language Chatbot: The design and implementation of English language transfer learning agent apps. In IEEE 3rd International Conference on Automation, Electronics and Electrical Engineering (AUTEEE) 403–407 (IEEE, 2020).

Lin, J., Zhao, L., Wang, Q., Ward, R. & Wang, J. DT-LET: Deep transfer learning by exploring where to transfer. Neurocomputing 390, 99–107 (2020).

Liu, Y., Liu, W., Yan, X., Guo, S. & Zhang, C. Adaptive transfer learning for PINN. J. Comput. Phys. 112291 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Transfer learning for deep neural network-based partial differential equations solving. Adv. Aerodyn. 3(1), 1–14 (2021).

Goswami, S., Anitescu, C., Chakraborty, S. & Rabczuk, T. Transfer learning enhanced physics informed neural network for phase-field modeling of fracture. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 106, 102447 (2020).

Shi, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Yi, J. & Cho-Jui, H. Fast certified robust training with short warmup. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 18335–18349 (2021).

Inda, A. J., Garcia, Shao, Y., Huang N. I. & Yu, W. Physics informed neural network (PINN) for noise-robust phase-based magnetic resonance electrical properties tomography. In 2022 3rd URSI Atlantic and Asia Pacific Radio Science Meeting (AT-AP-RASC) 1–4 (IEEE, 2022).

Yan, J., Chen, X., Wang, Z., Zhoui, E. & Liu, J. ST-PINN: A self-training physics-informed neural network for partial differential equations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09389 (2023).

Penwarden, M., Jagtap, A. D., Zhe, S., Karniadakis, G. E. & Kirby, R. M. A unified scalable framework for causal sweeping strategies for Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and their temporal decompositions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.14227 (2023).

Haghighat, E., Raissi, M., Moure, A., Gomez, H. & Juanes, R. A physics-informed deep learning framework for inversion and surrogate modeling in solid mechanics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 379, 113741 (2021).

Uddin, Z., Ganga, S., Asthana, R. & Ibrahim, W. Wavelets based physics informed neural networks to solve non-linear differential equations. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2882 (2023).

Chiu, P. H., Wong, J. C., Ooi, C., Dao, M. H. & Ong, Y.S. CAN-PINN: A fast physics-informed neural network based on coupled-automatic–numerical differentiation method. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 395, 114909 (2022).

Zhou, Wen, S., Miwa & Okamoto, K. Advancing fluid dynamics simulations: A comprehensive approach to optimizing physics-informed neural networks. Phys. Fluids 36, 1 (2024).

Bai, J., Rabczuk, T., Gupta, A., Alzubaidi, L. & Gu, Y. A physics-informed neural network technique based on a modified loss function for computational 2D and 3D solid mechanics. Comput. Mech. 71(3), 543–562 (2023).

Sharma, P., Evans, L. & Tindall, M. Stiff-PDEs and physics-informed neural networks. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30(5), 2929–2958 (2023).

Lu, L., Meng, X., Mao, Z. & Em Karniadakis, G. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Rev. 63(1), 208–228 (2021).

Nabian, M. A., Gladstone, R. J. & Meidani, H. Efficient training of physics-informed neural networks via importance sampling. Comput. Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 36(8), 962–977 (2021).

Gao, W. & Wang, C. Active learning based sampling for high-dimensional nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 475, 111848 (2023).

Tang, K., Wan, X. & Yang, C. DAS-PINNs: A deep adaptive sampling method for solving high-dimensional partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 476, 111868 (2023).

Zeng, S., Zhang, Z. & Zou, Q. Adaptive deep neural networks methods for high-dimensional partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 463, 111232 (2022).

Hanna, J. M., Aguado, J. V., Comas-Cardona, S., Askri, R. & Borzacchiello, D. Residual-based adaptivity for two-phase flow simulation in porous media using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 396, 115100 (2022).

Wang, S., Teng, Y. & Perdikaris, P. Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 43(5), A3055–A3081 (2021).

Jin, X., Cai, S., Li, H. & George Em, K. NSFnets (Navier-Stokes flow nets): Physics-informed neural networks for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. J. Comput. Phys. 426, 109951 (2021).

Maddu, S., Sturm, D., Müller, C. L. & Ivo, F. Sbalzarini. Inverse dirichlet weighting enables reliable training of physics informed neural networks. Mach. Learning: Sci. Technol. 3(1), 015026 (2022).

Ye, S. et al. A flow feature detection method for modeling pressure distribution around a cylinder in non-uniform flows by using a convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 10, 4459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61450-z (2020).

Pawar, S., San, O., Vedula, P., Rasheed, A. & Kvamsdal, T. Multi-fidelity information fusion with concatenated neural networks. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 5900 (2022).

Guo, H., Zhuang, X., Fu, X., Zhu, Y. & Rabczuk, T. Physics-informed deep learning for three-dimensional transient heat transfer analysis of functionally graded materials. Comput. Mech. 72(3), 513–524 (2023).

Arka Daw, J., Bu, S., Wang, P., Perdikaris & Karpatne, A. July. Mitigating propagation failures in Physics-informed neural networks using retain-resample-release (R3) sampling. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning 7264–7302. PMLR, ISSN: 2640–3498 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Deputy of Research and Technology of Sharif University for providing a suitable working environment to conduct the experiments and acknowledge Miss. Mina Rezaie & Mr. Ehsan Ghaderi for their helpful and kind support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mahyar Jahani-nasab; Methodology & writing Mohamad Ali Bijarchi; review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jahani-nasab, M., Bijarchi, M.A. Enhancing convergence speed with feature enforcing physics-informed neural networks using boundary conditions as prior knowledge. Sci Rep 14, 23836 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74711-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74711-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Application of physics-informed neural networks for solving water penetration problems in unsaturated soils

Engineering with Computers (2026)

-

Study of intelligent home environment system based on big data and improved k-means algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Physics-informed neural networks with hybrid Kolmogorov-Arnold network and augmented Lagrangian function for solving partial differential equations

Scientific Reports (2025)