Abstract

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often result in sudden and persistent reduction in health-related quality of life (HRQoL), which may be alleviated with palliative care. Among individuals with COPD, we aimed to investigate potential associations between HRQoL at admission with CAP and the risk of re-hospitalization and mortality and potential associations between specific HRQoL domains and CAP treatment outcomes. HRQoL was assessed at admission and the participants were grouped into tertiles based on the HRQoL utility index and specific domains. The results revealed that participants in the middle and highest tertiles of HRQoL had a lower 90-day re-hospitalization risk compared to those in the lowest tertile, whereas no differences in re-hospitalization risk were observed 30 and 180 days after discharge. Almost one in four had severe pain or discomfort at admission and the domain pain or discomfort emerged as a predictor of re-hospitalization. In addition, participants in the middle and highest tertiles had lower risk of 180-day mortality compared to those in the lowest, while no differences were observed in 30-day or 90-day mortality risk. An increased focus on in-hospital palliative care could alleviate the pain and discomfort reported by many participants with potential to reduce re-hospitalization rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common cause of hospitalization among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)1 with an up to 18-fold higher incidence of hospitalization with CAP among individuals with COPD compared to those without COPD2.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instruments are widely used to determine physical, functional, social, and psychosocial well-being from the patient’s perspective3. Low HRQoL is common among individuals with COPD4, especially in the advanced stages. The main causes of low HRQoL in COPD is due to reductions in physical, psychological, and social aspects5 likely all influenced by high-grade dyspnea.

CAP is an acute lower respiratory tract infection with respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnea6. In COPD, CAP may cause an acute worsening of existing respiratory symptoms, a so-called acute exacerbation. Moderate to severe acute exacerbations are associated with sudden and persistent impairment in HRQoL7, and exacerbations requiring hospitalizations have a higher impact on HRQoL compared to exacerbations treated in outpatient facilities7. Palliative care focuses on alleviating symptoms and improving HRQoL8. In COPD, palliative care is complicated due to unpredictability and heterogeneity in disease progression and presentation and is therefore often restricted to the terminal phase9. However, palliative care is relevant at all stages of COPD8.

While studies on HRQoL among individuals with COPD are mainly cross-sectional, conducted at outpatient facilities10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, or at discharge from the hospital20, there is little knowledge on the association between HRQoL at hospital admission and the prognosis in individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP.

We hypothesized that a higher HRQoL captured shortly after admission is associated with a better prognosis among individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP and that some domains would emerge as predictors and thereby potential focus areas for clinical practice and further research. The overall aim of this study was to investigate the potential association between HRQoL at admission and the risk of re-hospitalization and mortality among individuals with COPD and CAP. We also aimed to investigate potential associations between specific domains of HRQoL and CAP treatment outcomes.

Methods

Population and design

This study was nested within the Surviving Pneumonia Cohort (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03795662), a prospective cohort study conducted at the Department of Pulmonary and Infectious Diseases at Copenhagen University Hospital – North Zealand in Denmark. Participants were recruited between January 2019 and March 2022. Inclusion criteria were a known COPD diagnosis, age ≥ 18 years and CAP at admission defined as a new pulmonary infiltrate on chest X-ray or computed tomography scan and minimum one symptom of CAP such as fever (≥ 38.0 °C), hypothermia (< 35.0 °C), cough, sputum production, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, or focal chest signs on auscultation. Exclusion criteria were lack of information on HRQoL and participation in interventional studies designed to improve the outcomes of interest (re-hospitalization and mortality). Participants were identified by screening at the emergency and medical wards and included within 24 h of hospital admission.

Data collection

Data related to measurements and questionnaires were conducted within 48 h of admission and included HRQoL, smoking history, information on weight loss, and anthropometry. Demographic characteristics and clinical data were collected from the electronic medical records.

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQoL (EQ) EQ-5D-5L questionnaire21. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire consists of five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. For each of the five domains, respondents chose a score from 1 (best score) to 5 (worst score). The individual domain scores were converted into an index value called the EQ utility score. Since the EQ-5D-5L instrument has no cut-offs for low, medium and high HRQoL, the study population was divided into tertiles based on the EQ utility score. The lowest tertile reflects the lowest EQ utility score (i.e., the lowest HRQoL). In addition, we categorized each domain of EQ-5D-5L into three groups: 1 point on the specific domain (best score), 2–3 points on the specific domain, and 4–5 points on the specific domain (worst score) for secondary analyses. The questionnaire was administered by face-to-face contact with a member of the project group who read the questions and typed the answer provided by the participant.

Anthropometry, nutritional categorization, and smoking history

Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg on an electronic scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany) and height was self-reported. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Fat-free mass was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BioScan touch i8, Maltron International Ltd, United Kingdom) and fat-free mass index was calculated as fat-free mass (kg)/height (m2). Participants were categorized as undernourished, well-nourished, overweight, or obese. Undernutrition was defined as either (1) a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or (2) unintentional weight loss (≥ 5% within 3 months or ≥ 10% within 12 months) combined with either an alternative cut-off of BMI (BMI < 20 kg/m2 if < 70 years of age or BMI < 22 kg/m2 if ≥ 70 years) or a low fat-free mass index (< 15 kg/m2 in females and < 17 kg/m2in males)22. Well-nourished was defined as a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2 without a self-reported unintentional weight. Participants with a BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and a BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2, were defined as overweight and obese, respectively, regardless of prior weight loss. Participants were asked about their smoking history throughout their lifetime and based on this categorized as never, previous, or current smokers.

Clinical data and outcomes

The most recent forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) registered in the electronic medical records was used as an indicator of lung function and to categorize participants according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) criteria as mild to moderate (FEV1 ≥ 50% of the predicted value), severe (FEV1 30–49% of the predicted value), and very severe (FEV1 < 30% of the predicted value)23. CAP severity was categorized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the CURB-65 instrument24. The Charlson comorbidity index was used to assess the combined burden of comorbidities25. The outcomes, re-hospitalization and mortality, were collected through medical records. Re-hospitalization was defined as a new hospital admission within 30, 90, and 180 days after discharge and mortality as death within 30, 90, and 180 days from the day of admission.

Statistical methods

All data were entered into the electronic database REDCap (https://redcap.regionh.dk/). Statistical analyses were carried out using STATA/IC version 17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed quantitative variables and mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were summarized as counts (%). Kaplan-Meier curves were used to illustrate mortality and re-hospitalization rates and logrank tests to compare the probabilities across the tertile groups. Tests of interaction between HRQoL and sex were conducted to assess whether associations between HRQoL and the outcomes (re-hospitalization and mortality) differed between males and females. The difference in risk of a minimum of one re-hospitalization within 30, 90, and 180 days after discharge was investigated using Cox regression with death as competing event. Participants without a re-hospitalization within 30, 90, and 180 days after discharge and participants who died after their first discharge without a re-hospitalization were censored. The differences in risk of mortality between the day of admission and 30, 90, and 180 days after the day of admission were investigated using logistic regression. The lowest tertile of the EQ utility score was used as the reference group in the main analyses. In the secondary analyses, the EQ domains with observed log-rank test differences, were investigated similarly to the main analyses. In these models, the best score (1 point in the specific EQ domain) was used as the reference group. Unadjusted and adjusted complete case models were conducted. As important covariates (FEV1, CURB-65, and nutritional status) had missing values, an adjusted model with imputed missing values was conducted for each outcome. The adjusted models included age, sex, FEV1, CURB-65, Charlson comorbidity index, and nutritional status as covariates. In the adjusted models, missing variables were imputed using multiple imputations through chained equations to create 10 imputed datasets with 100 iterations per dataset26,27. All variables with missing values were assumed to be missing at random. The imputation included the following predictor variables: age, sex, EQ utility score, Charlson comorbidity index, smoking, re-hospitalization (30-day, 90-day, and 180-day), and mortality (30-day, 90-day, and 180-day). Results were reported as hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR), as appropriate, with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

The Surviving Pneumonia Cohort was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee at the Capital Region of Denmark (H-18024256), registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03795662), and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided oral and written informed consent before enrolment.

Results

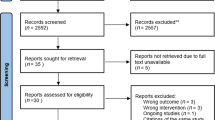

The flow of inclusion is illustrated in Fig. 1. Among 253 participants with COPD and CAP included in the Surviving Pneumonia cohort, 147 (58%) were included in the current study. In total, 106 individuals were excluded, of whom 4 withdrew, 36 participated in interventions, and 66 had no information on HRQoL. There were no differences in age, sex, FEV1, CURB-65, Charlson comorbidity index, re-hospitalization, or mortality between non-participants and participants (data not shown).

Characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The overall median (IQR) EQ utility score was 0.59 with scores of 0.28 (0.16–0.38), 0.59 (0.54–0.64), and 0.79 (0.73–0.82) in the lowest, middle, and highest tertiles, respectively. The mean (SD) age was 74.4 (9.9) years. The median (IQR) FEV1 was 44 (32–59), and more than half (58%) had severe COPD, and 17 (13%) had severe CAP. The proportion of females was 63%, 47%, and 45% in the lowest, middle, and highest tertiles, respectively. Looking at the EQ domains, severe impairment in mobility was reported by 39%, severe impairment in both usual activities and self-care by 24%, severe pain or discomfort by 23%, and severe anxiety or depression by 10% (Supplementary Table 1). The overall 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day re-hospitalization rates were 37%, 46%, and 62%, respectively, whereas the overall 30-day, 90-day, and 180-day mortality rates were 10%, 14%, and 22.5%, respectively.

Of the 147 participants, 60 (41%) had incomplete data on minimum one covariate variable. HRQoL was higher among participants with complete data compared to participants with incomplete data (median EQ utility of 0.62 versus 0.52). No differences in age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index, re-hospitalization, or mortality were observed between participants with complete and incomplete data (data not shown).

Regarding both outcomes (re-hospitalization and mortality), no interactions were observed between sex and HRQoL at any of the time points.

Risk of re-hospitalization

Compared to participants in the lowest tertile, participants in the middle and highest tertiles had 54% (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.3; 0.8) and 41% (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.4; 0.9) lower risk of 90-day re-hospitalization, respectively. There were no differences in 30-day and 180-day re-hospitalization risks between participants in the lowest and participants in the middle or highest tertiles of HRQoL (Table 2). There were differences in probability of avoiding a re-hospitalization according to the degree of pain or discomfort at admission (Fig. 2). Some to moderate pain or discomfort was associated with a higher risk of 30-day re-hospitalization (HR: 2.2, 95% CI 1.1; 4.7) compared to no pain or discomfort, whereas there was no difference in the risk of 90-day and 180-day re-hospitalization (90 days: HR: 1.4, 95% CI 0.9; 2.4; 180 days: HR: 1.3, 95% CI 0.9; 2.1). Compared to no pain or discomfort, severe pain or discomfort was associated with a higher risk of 30-day (HR: 2.8, 95% CI 1.3; 6.2) and 90-day (HR: 1.9, 95% CI 1.1; 3.2) re-hospitalization, whereas there was no difference in the 180-day re-hospitalization risk (HR: 1.4, 95% CI 0.9; 1.8) (Table 3).

Risk of mortality

No difference in the risk of 30-day and 90-day mortality was observed between the lowest tertile and the middle or highest tertiles of HRQoL (Table 4). Participants in the middle and highest tertiles had 80% (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.1; 0.7) and 69% (OR: 0.31; 95% CI 0.1; 0.9) lower risk of 180-day mortality compared to participants in the lowest tertile. There were differences in probability of survival according to the degree of ability to perform selfcare and usual activities (Fig. 3). Neither impairment in self-care nor usual activities (some to medium) were associated with a higher risk of 30-day and 90-day mortality compared to full ability. Some to medium impairment in both self-care and usual activities were associated with higher risk of 180-day mortality compared to no impairment in self-care and usual activities (OR: 4.2, 95% CI 1.3; 14.1). Severe impairment in self-care and usual activities were not associated with higher risk of 180-day mortality compared to no impairment in usual activities and selfcare(Table 5).

Discussion

Among individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP, we found that a higher HRQoL at admission was associated with a lower risk of re-hospitalization within the first 90 days after discharge and lower risk of mortality within 180 days from the day of admission. A high proportion had severe pain or discomfort at admission, indicating a need for in-hospital palliative care.

The overall median EQ utility score was 0.59, which is lower than the EQ utility score of 0.80 reported among the general aged population (≥ 70 years)28. We observed a higher proportion of females among participants with lower HRQoL. It seems that there is a tendency that males and females rate their health differently across different conditions (including COPD) as well as in the general population29,30,31,32,33,34. However, our interaction analyses showed that the identified associations between HRQoL and re-hospitalization or mortality did not differ between females and males with COPD hospitalized with CAP.

In our study population, the overall re-hospitalization rate was high, especially among those with the lowest HRQoL. Similar re-hospitalization rates have been observed among individuals with acute exacerbation of COPD20,34. However, these individuals were followed six months longer than our study population. Especially the degree of pain or discomfort at admission increased the likelihood of 30-day and 90-day re-hospitalization. Almost one in four reported having severe to extreme pain or discomfort. The EQ-5D-5L instrument does not distinguish between pain or discomfort and anxiety or depression. Discomfort is not a well-defined concept, and pain, anxiety and depression are all potential causes of discomfort35. Addressing discomfort is an important care goal in the hospital setting, especially in critically ill patients. Overall, discomfort can be divided into physical and psychological discomfort with strong associations between some of the causes. In addition to pain, physical causes of discomfort include fatigue, sleeplessness, and breathlessness. Psychological discomfort includes unpleasant emotions that could result in anxiety, depression, embarrassment, and isolation35. Coexistence of anxiety and dyspnea is an example of strongly related physical and psychological discomfort, which is common in COPD exacerbations. Only 10% reported having severe to extreme anxiety or depression, and surprisingly we found no association between anxiety or depression and re-hospitalization or mortality. A possible explanation is that anxiety (psychological discomfort) and breathlessness (physical discomfort) are closely related36, and some participants may have connected their respiratory distress to discomfort rather than anxiety per se. It is also possible that morphine relief has been provided to some participants before data collection, which potentially can affect the reporting of pain, discomfort, and anxiety, but we do not have the data. Morphine is offered as part of clinical practice for treating individuals with COPD as relief of dyspnea and anxiety37. Therefore, anxiety might be underestimated in this study. Individuals with COPD experience slowly progressing respiratory failure. A major focus of COPD treatment is alleviating the psychological stress associated with chronic dyspnea and acute worsening of the respiratory symptoms, especially in end-stage COPD with anxiolytics and opioids37. Acute exacerbations and CAP worsen the respiratory symptoms, resulting in sudden and lasting reductions in HRQoL7especially caused by reductions in physical, functional and phycological aspects5. Our results underscore a need for in-hospital palliative care in individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP. In-hospital palliative care has been shown to reduce re-hospitalization in individuals with critical medical conditions (cancer, COPD, heart failure, liver failure, kidney failure, and AIDS) with a short life expectancy of up to one year38,39. Palliative care for individuals with COPD is often inadequate39and, in many cases, restricted to the terminal phase, likely due to restricted capacity and insufficiently trained health care providers9. Palliative care is relevant at all stages of COPD, and an increased focus on in-hospital palliative care could be a beneficial strategy to alleviate discomfort among individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP. Future research should investigate whether an increased focus on in-hospital palliative care during hospitalization with CAP among individuals with COPD could reduce the re-hospitalization risk.

Our results indicated that lower HRQoL was associated with a higher risk of 180-day mortality. In non-hospitalized individuals with COPD, low HRQoL has been associated with a higher risk mortality19,40. Impairment in functional ability (usual activities and self-care) seems to be the main predictor of mortality in this population. Functional ability is also included in several other instruments including frailty scores and the Barthel index (ability to perform daily activities independently). Frailty has been associated with increased risk of mortality among patients hospitalized with CAP41. We have previously reported that a low Barthel Index at admission with CAP was associated with a higher risk of re-hospitalization and mortality (not only COPD patients)42. It is uncertain if a focus on avoiding further functional decline through in-hospital and post-discharge exercise training could improve survival in vulnerable patient groups.

In this study population, different follow-up periods appeared as important for the two outcomes of interest. The explanation for this is likely found in the specific domains. The association between HRQoL and re-hospitalization was driven by the domain pain or discomfort at admission as some to moderate pain or discomfort was associated with higher 30-day re-hospitalization risk and severe pain or discomfort with both higher 30-day and 90-day re-hospitalization risk. The association between HRQoL and mortality was driven by low functional ability at admission indicating that those with a self-reported low functional status are more vulnerable. A similar finding has been reported among acutely hospitalized elderly, where a higher admission HRQoL was linked to higher survival rates and reduced functional decline up to three months after discharge43. This study included follow-up three and 12 months after discharge. It is therefore uncertain if they would also find an association at 180 days after discharge. We did not find an association between admission HRQoL and mortality three months after discharge, likely due to the low mortality rate of 10% at this time point combined with the relatively small sample.

A strength of this study is that HRQoL is determined by a generic HRQoL instrument that has been validated in individuals with COPD44. Instead of using admission HRQoL, we could also have chosen HRQoL at discharge. However, we have several arguments for using admission HRQoL, including the preventive potential of identifying specific domains as target areas during admission. Moreover, HRQoL captured at discharge had more missing values, mainly caused by uncertainty about when participants were discharged. Disease-specific HRQoL instruments are focused on disease-specific aspects and thereby differ from generic instruments using a more holistic approach45. Thereby, generic HRQoL instruments may be superior to the disease-specific instruments in integrating the combined influence of all comorbidities on HRQoL11. Comorbidities are common in individuals with COPD, and a higher burden of comorbidities is likely associated with lower HRQoL. Therefore, we consider it a strength to use a generic instrument, even though we acknowledge both instruments as relevant. Additional strengths include information on important confounders (nutritional status, comorbidities, FEV1). A limitation is the potential risk of selection bias when recruiting patients hospitalized with acute illnesses such as CAP, since individuals with the most severe disease may decline to participate. Further among included participants, severely ill ones likely have a higher dropout rate compared to those with milder disease. To avoid attrition bias related to lacking follow-up data, participants were given the option to only allow using their medical record for future follow-up. Another potential limitation was missing data, which is why we used imputation. Looking at the results in Table 2, there are obvious disagreements in the results based on the adjusted model analyzing the raw data (complete case model) compared to the model using imputed covariate data. Using imputation, a valid statistical model, is considered a strength as this model have more statistical power and the imputed variables are considered important potential confounders. HRQoL was captured up to 48 h after admission, which may be a limitation since some domains might be rated differently by some participants immediately after arrival at the hospital. Also, we had to exclude 66 (27%) with no data on admission HRQoL. Lacking project resources is the main reason for missing HRQoL upon admission. For purposes that require data that is part of routine care, missing information is very limited, whereas data collection requiring face-to-face contact is more challenging, especially among acutely ill participants hospitalized in a busy medical ward. However, the comparison between eligible and ineligible patients showed that there was no difference in available relevant characteristics such as comorbidities, age, sex, FEV1, CAP severity as well as the outcome measures. The FEV1 and classification of the COPD stage may also have limitations. Firstly, besides FEV1, we did not have data to classify according to the widely used GOLD ABCD23or GOLD ABE46 assessment tools. Secondly, there may be great variation in how long it has been since the last FEV1 measurement (the date of the procedure was unknown). It is therefore likely that lung function has deteriorated in some participants since the measurement.

Conclusion

Among individuals with COPD hospitalized with CAP, those with a relatively higher HRQoL were at lower risk of re-hospitalization and mortality. Increased focus on in-hospital palliative care could alleviate the pain or discomfort reported by many participants with potential to reduce re-hospitalization rates.

Data availability

Since the dataset used for the current study is not published, the data set can be accessed in a pseudonymized form, by reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Wier, L. M., Elixhauser, A., Pfuntner, A. & Au, D. H. Overview of Hospitalizations among Patients with COPD, 2008. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs [Internet] 2011; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53969/

Bordon, J. et al. Hospitalization due to community-acquired pneumonia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence, epidemiology and outcomes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26 (2), 220–226 (2020).

Megari, K. Quality of life in Chronic Disease patients. Health Psychol. Res. 1 (3), e27 (2013).

Janson, C. et al. The impact of COPD on health status: findings from the BOLD study. Eur. Respir J. 42 (6), 1472–1483 (2013).

Paap, M. C. et al. Identifying key domains of health-related quality of life for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the patient perspective. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 12, 106 (2014).

Torres, A. et al. Pneumonia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7 (1), 25 (2021).

Guo, J., Chen, Y., Zhang, W., Tong, S. & Dong, J. Moderate and severe exacerbations have a significant impact on health-related quality of life, utility, and lung function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 78, 28–35 (2020).

Lanken, P. N. et al. An official American thoracic Society Clinical Policy Statement: Palliative Care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 177 (8), 912–927 (2008).

Broese, J. M. C., van der Kleij, R. M. J. J., Verschuur, E. M. L., Kerstjens, H. A. M. & Engels, Y. Chavannes N.H. implementation of a palliative care intervention for patients with COPD - a mixed methods process evaluation of the COMPASSION study. BMC Palliat. Care. 21 (1), 219 (2022).

Acharya Pandey, R., Chalise, H. N., Shrestha, A. & Ranjit, A. Quality of life of patients with chronic obstructive Pulmonary Disease attending a Tertiary Care Hospital, Kavre, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ). 19 (74), 180–185 (2021).

Wacker, M. E. et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in COPD: comparing generic and disease-specific instruments with focus on comorbidities. BMC Pulm Med. 16 (1), 70 (2016).

Kharbanda, S. & Anand, R. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a hospital-based study. Indian J. Med. Res. 153 (4), 459–464 (2021).

Ibrahim, S., Manu, M. K., James, B. S., Kamath, A. & Shetty, R. Health Related Quality of Life among patients with chronic obstructive Pulmonary Disease at a tertiary care teaching hospital in southern India. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health. 10, 100711 (2021).

Pati, S. et al. An assessment of health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases attending a tertiary care hospital in Bhubaneswar City, India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 7 (5), 1047–1053 (2018).

Assaf, E. A., Badarneh, A., Saifan, A. & Al-Yateem, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients’ quality of life and its related factors: a cross-sectional study of the Jordanian population. F1000Res. 11, 581 (2022).

Esteban, C. et al. Predictive factors over time of health-related quality of life in COPD patients. Respir Res. 21 (1), 138 (2020).

Kushwaha, S. et al. Health-related quality of life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a hospital-based study. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 9 (8), 4074–4078 (2020).

Henoch, I., Strang, S., Löfdahl, C. G. & Ekberg-Jansson, A. Health-related quality of life in a nationwide cohort of patients with COPD related to other characteristics. Eur. Clin. Respir J. 3, 31459 (2016).

Fan, V. S., Curtis, J. R., Tu, S. P., McDonell, M. B. & Fihn, S. D. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project investigators. Using quality of life to predict hospitalization and mortality in patients with obstructive lung diseases. Chest. 122 (2), 429–436 (2002).

Gudmundsson, G. et al. Risk factors for rehospitalisation in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depression. Eur. Respir J. 26 (3), 414–419 (2005).

Herdman, M. et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 20 (10), 1727–1736 (2011).

Cederholm, T. et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN Consensus Statement. Clin. Nutr. 34 (3), 335–340 (2015).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. (2020).

Lim, W. S. et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 64 (Suppl 3), iii1–55 (2009).

Quan, H. et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173 (6), 676–682 (2011).

Marshall, A., Altman, D. G., Royston, P. & Holder, R. L. Comparison of techniques for handling missing covariate data within prognostic modelling studies: a simulation study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 10, 7 (2010).

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C. & Leaf, P. J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr Res. 20 (1), 40–49 (2011).

Grochtdreis, T., Dams, J., König, H. H. & Konnopka, A. Health-related quality of life measured with the EQ-5D-5L: estimation of normative index values based on a representative German population sample and value set. Eur. J. Health Econ. 20 (6), 933–944 (2019).

Gayay A., Tapia J., Anguita M., Formiga F., Almenar L., Crespo-Leiro M. G., et al. Gender differences in Health-Related Quality of Life in patients with systolic heart failure: results of the VIDA Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092825 (2020).

Gijsberts, C. M. et al. Gender differences in health-related quality of life in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Open. Heart. 2 (1), e000231 (2015).

Cherepanov, D., Palta, M., Fryback, D. G. & Robert, S. A. Gender differences in health-related quality-of-life are partly explained by sociodemographic and socioeconomic variation between adult men and women in the US: evidence from four US nationally representative data sets. Qual. Life Res. 19 (8), 1115–1124 (2010).

de Torres, J. P. et al. Gender associated differences in determinants of quality of life in patients with COPD: a case series study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 4, 72 (2006).

Naberan, K., Azpeitia, A., Cantoni, J. & Miravitlles, M. Impairment of quality of life in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 106 (3), 367–373 (2012).

Osman, I. M., Godden, D. J., Friend, J. A., Legge, J. S. & Douglas, J. G. Quality of life and hospital re-admission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 52 (1), 67–71 (1997).

Ashkenazy, S. & DeKeyser, G. F. The differentiation between Pain and Discomfort: a Concept analysis of discomfort. Pain Manag Nurs. 20 (6), 556–562 (2019).

Lungeforeningen. Palliativ indsats til KOL-patienter. En deskriptiv undersøgelse af danske KOL-patienters sygdomsforløb og behov for palliativ indsats. (2013).

Mahler, D. A. et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 137 (3), 674–691 (2010).

May, P. et al. Evaluating hospital readmissions for persons with serious and complex illness: a competing risks Approach. Med. Care Res. Rev. 77 (6), 574–583 (2020).

Adelson, K. et al. Standardized criteria for Palliative Care Consultation on a Solid Tumor Oncology Service reduces downstream Health Care Use. J. Oncol. Pract. 13 (5), e431–e440 (2017).

Domingo-Salvany, A. et al. Health-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 166 (5), 680–685 (2002).

Luo, J., Tang, W., Sun, Y. & Jiang, C. Impact of frailty on 30-day and 1-year mortality in hospitalised elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 10 (10), e038370 (2020).

Ryrsø, C. K., Hegelund M. H., Dungu A. M., Faurholt-Jepsen D., Pedersen B. K., Ritz C., et al. Association between Barthel Index, Grip Strength, and Physical Activity Level at Admission and Prognosis in Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 11(21). (2022).

Parlevliet, J. L., MacNeil-Vroomen, J., Buurman, B. M., de Rooij, S. E. & Bosmans, J. E. Health-Related Quality of Life at Admission is Associated with Postdischarge Mortality, Functional decline, and institutionalization in acutely hospitalized Older Medical patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64 (4), 761–768 (2016).

Nolan, C. M. et al. The EQ-5D-5L health status questionnaire in COPD: validity, responsiveness and minimum important difference. Thorax. 71 (6), 493–500 (2016).

Assari, S., Lankarani, M. M., Montazeri, A., Soroush, M. R. & Mousavi, B. Are generic and disease-specific health related quality of life correlated? The case of chronic lung disease due to sulfur mustard. J. Res. Med. Sci. 14 (5), 285–290 (2009).

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2023).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the research nurses Malene Pilegaard Schønnemann, Hanne Hallager, and Christina Brix for their technical assistance. We also acknowledge Pelle Trier Petersen for his guidance in conducting the multiple imputations.

Funding

The Research Council at Copenhagen University Hospital, North Zealand, Denmark, and Helsefonden (19-B-0155) provided financial support for the current study without any involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, or deciding where to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed and conceptualized by M.H.H., D.F.-J. M.F.O., C.R., R.K.-M., and B.L. Data acquisition was led by M.H.H., C.K.R., and A.M.D. Verification of the underlying data was done by M.H.H. Data analysis was led by M.H.H., D.F.-J., L.J., and C.R. Data interpretation was led by M.H.H., D.F.-J., M.F.O., C.R., B.L., R.K.-M., L.B., and A.V.J. The manuscript was drafted by M.H.H. and L.J. All authors have critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version, and are accountable for all aspects of the work and those listed as authors qualify for authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hegelund, M.H., Jagerova, L., Olsen, M.F. et al. Health-related quality of life predicts prognosis in individuals with COPD hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia – a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep 14, 27315 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74933-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74933-0