Abstract

From the time of discovery, CH3NH3SnI3 has been a promising candidate in photovoltaics due to its outstanding optoelectronic properties. However, stabilization was not easy to achieve in CH3NH3SnI3-based solar cells. Because CH3NH3SnI3 was used as an absorber, its naturally-occurring self-doping property spontaneously modified band alignment, which increased carrier recombination and decreased the efficiency of solar cell gradually. In this paper, for the first time, we have presented detailed study on use of CH3NH3SnI3 as a hole transport layer in prototype solar cell having configuration: CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS/CdS/ZnO/AZO, using SCAPS software. To understand the effect of spontaneous self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 on solar cell performance, the analysis of variation in solar cell performance parameters, band alignment conduction band, valance band, Fermi levels, charge density, current density, conductance, capacitance and recombination rate was performed as a function of increasing CH3NH3SnI3 carrier concentration. It was found that, when used as an hole transport layer, the inherent self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 became a helpful trait to increase hole extraction and spontaneously enhanced our device efficiency. Thus, the inherent self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 transformed from curse to boon when we leveraged CH3NH3SnI3 as an hole transport layer in our solar cell device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The earth’s environment is continuously being degraded by the excessive use of conventional energy sources such as coal and fossil fuels to power our daily needs. Hence, to protect our environment, it is quite imperative to research on the renewable sources of energy1. Among various renewable energy sources such as wind energy and hydro energy, the only renewable energy which can be generated easily at individuals’ homes is the solar energy. Thus, efforts are made to advance the photovoltaic technology in our research2,3,4,5,6.

Perovskite materials have recently emerged as promising candidates in the photovoltaic research owing to its attractive features such as good charge carrier mobility, large carrier diffusion length, small exciton binding energy, close-to-ideal bandgap and lower environmental toxicity7,8. This aspect of perovskite materials has even encouraged the researchers at the Technical University of Munich to utilize variety of perovskite and organic solar cells (SCs) for the space missions. Their remarkable results reaffirmed the strong potential of perovskite materials as a truly promising photovoltaic substance. Moreover, as the lead-based perovskite solar cells (PSCs) had serious toxicity and decomposition issues, its counterpart i.e., the tin-based perovskite materials have recently grabbed tremendous attention from the scientific community.

Purpose of study

Owing to their outstanding properties, the current state-of-the-art certified tin-based PSCs are showing commendable improvement in its power conversion efficiency (PCE) and are very rapidly approaching its calculated Shockley-Queisser Limit of 32.91%9. However, tin-based PSCs has a serious drawback. The obstacle behind its commercialization is its decreasing efficiency within the duration of just few months of installation7,10. To analyze the stability of device with aging, recent study by Mcmeekin et al. has reported that the PCE of their champion device drops down by 20% in 1410 h of operation, which accounts for nearly 8.5 weeks of continuous usage11. Also, the recent research by Lui et al. reports the device efficiency decay by 10% in 1000 h or nearly 6 weeks of continuous illumination12. Further, the stability of PSCs is highly sensitive to operational and environmental conditions. Apart from its aging, noticable detorioration of PSC is observed within hours to days of exposure to higher humidity conditions13. Oxygen and light can degrade its performance within hours to few weeks depending on extremity14. PCE of PSCs also degrade due to ion migration (hysteresis) in the matter of days to weeks15, and due to thermal stress within weeks to months16.

Thus, the entire scientific community now-a-days, is largely interested in preventing this PCE decay to improve the stability of tin-based PSCs17. The core reason behind this stability issue is the inherent property of spontaneous self-doping in CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite. The Sn+ 2 state undergoes spontaneous oxidation to Sn+ 4 and release more p-type dopants. This increases the carrier recombination rate due to increased recombination centers18, which is responsible for significant decay in device performance and stability with time, within the duration of just few months of installation7. Actually, on a microscopic level, the air atmosphere leads to increment in the rate of this self-doping in CH3NH3SnI310,19,20,21,22. This degraded the performance of SCs researched till date. This drawback is the main obstacle behind commercialization of these cost-friendly and eco-friendly tin-based PSCs over silicon-based SCs23.

Therefore, a lot of research is being held all over the world to address this stability issue of tin-based PSCs. Since self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 is understood as the reason for SC degradation, scientists globally, are trying to cease this naturally-occurring self-doping process in CH3NH3SnI3 by adopting various chemical routes. Numerous strategies such as doping various SnX2 additives (X = F, Cl, Br) in varying concentrations, comproportionation, atmosphere reducing, solvent engineering, use of non-halide reducing agents, crystal growth control, etc10,20,21,24,25,26,27. are currently being thoroughly explored to prevent the occurrence of this self-doping process. Despite ample of research, we have currently reached the efficiency, performance and stability of tin-based PSCs to only half of that offered by toxic lead-based PSCs21. Hence, a lot of research still needs to be done to improve the efficiency and stability of tin-based PSCs.

Scientists Khadka et al. and Sharif et al.28,29 also reviewed CH3NH3SnI3-based SCs and presented numerous chemical routes to stabilize them. However, stabilization was not easy to achieve in those SC systems. If we analyse this more precisely, achieving stabilization in those SC systems proved to be quite challenging because perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 was used as an absorber. If CH3NH3SnI3 is used as an absorber, its self-doping property caused spontaneous modification in the energy band diagram of SC. Due to spontaneous increment in carrier concentration in CH3NH3SnI3 absorber, the recombination rate at interfaces increased. This reduced the efficieny of the hole extraction process. Hence, this reduced the PCE of CH3NH3SnI3-based SCs with time, and led to its detorioration. Here, when used as an absorber, the main reason behind reduced SC lifetime was the inherent spontaneous self-doping in CH3NH3SnI3.

What if, instead of using perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 as an absorber, we treat it as a hole transport layer (HTL)! Practically, the perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 is a p-type doped material. Hence, treating it as an HTL can be perfectly viable. On implementation of perovskite CH3NH3SnI3 as an hole transport layer (HTL), its naturally-occurring self-doping can increase hole mobility and conductivity within HTL. As a result, the holes can be extracted more efficiently. This can potentially turn its inherent spontaneous self-doping property from curse to boon i.e., make it the main reason for enhancement in SC efficiency spontaneously. Thus, whenever the SC system will be exposed to air atmosphere, it will not detoriorate due to perovskite’s self-doping property. Now, in terms of stability, the perovskite HTL film can be considered as good as other HTL films. This is the strategy that is implemented in our paper. We have leveraged the inherent naturally-occurring self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite as a helpful trait to enhance the PCE of our SC spontaneously.

The lifetime of a film reduces if its crystal structure is harmed in any way. Since spontaneous self-doping in CH3NH3SnI3 transforms Sn+ 2 to Sn+ 4 and lead to increment in carrier concentration in perovskite film, it doen’t affect the crystal structure of material. Thus, if a proper synthesis technique is followed to synthesize good quality CH3NH3SnI3 HTL film, the lifetime of HTL film in this case, will be maintained as long as its crystal structure is preserved.

Thus, previously, the tin-based perovskite material (CH3NH3SnI3) was being used as an absorber layer as it offers high absorption coefficient7. In this paper, for the first time, we adopted a new approach to treat CH3NH3SnI3 as a HTL. To transform the inherent spontaneous self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite from curse to boon, we introduce it as a possible new application of Sn-based perovskite material within SC systems in this paper. We intend to transform the inherent self-doping oxidation property of CH3NH3SnI3 as an advantage for SC. Thus, this phenomenon is harnessed to uplift the performance efficiency of SC spontaneously with time. To achieve this, CH3NH3SnI3 may be the best suitable HTL for CZTS-based SCs. This can be proved by our analysis which indicates the potential of spontaneously increasing CH3NH3SnI3 HTL carrier concentration to enhance the PCE of any SC spontaneously with time.

Such devices with perovskite HTL film are meant to possess a planar n-i-p architecture to avoid strong photon absorption in HTL by perovskite material. Liu et al. found that the doping concentration in CH3NH3SnI3 rises above 1021 cm-3 spontaneously with time26. Hence, study concerning evolution of SC parameters due to variation in HTL charge carrier concentration is presented over a broader range from 1014 cm to 3 to 1022 cm-3 in this work. Beyond doping concentration of 1022 cm-3, the semiconductor CH3NH3SnI3 might become degenerate semiconductor.

Purpose behind simulation study

Our rich scientific history demonstrates that any novel concept needs detailed theoretical foundation to unveal the hidden science behind the happening, for its proper establishment30,31,32,33. Thus, various connections between numerous microscopic and macroscopic aspects of solar cells are established in this paper using simulation technology. Fortunately, as the theoretically-obtained and experimentally-extracted values of SC parameters affected by variation of carrier concentration, are in good agreement34, its intensive analysis became possible to be performed using simulation technology. As simulation allowed us to observe the variation in various SC parameters with variation in HTL carrier concentration, we could properly test our strategy and predict positive results. Thus, our theoretical simulation research includes establishment of a novel strategy of utilizing the inherent spontaneous self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite as a helpful trait to enhance PCE of SC spontaneously with time, and identifies it as a promising direction for experimental research, thereby making future experimental efforts more targeted and efficient.

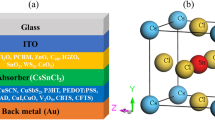

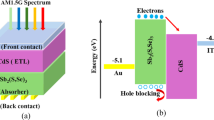

As an HTL, CH3NH3SnI3 provides good band alignment with CZTS absorber. The good band tuning between CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS heterojunction is consistent with the research by Reyes et al., Islam et al. and Mohanty et al.35,36,37. Moreover, as electron transport layer (ETL), CdS/ZnO/AZO provide suitable band offset with CZTS absorber for easy collection of electrons. This is in line with the observations presented by Cantas et al., Perlikowski et al., Mutiari et al., and Routray et al.38,39,40,41. Thus, we present study of SC having configuration: CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS/CdS/ZnO/AZO.

The same configuration without CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL layer provided 4.1% (Mo/CZTS/CdS/ZnO) and 6.77% (Mo/CZTS/CdS/ZnO: Al) to Schubert et al.42 and Katagiri et al.43, respectively. On the other hand, when CH3NH3SnI3 is used as an HTL in this paper, the SC achieved PCE upto 19.63%. Moreover, the spontaneous self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 helped use to spontaneously enhance the PCE of our SC by 12.8% from 17.4% at HTL doping concentration of 1016 cm-3, to 19.63% at HTL doping concentration of 1021 cm-3. Thus, the proposed SC may provide a viable path for the high-efficiency, stable, eco-friendly as well as cost-friendly SC devices.

Methodology

As an absorber, CZTS offers high absorption coefficient of 104 to 105 cm− 1, direct bandgap characteristics, elemental abundance, non-toxicity, production stability, high-performance and low price44. Thus, we opted to explore CZTS-based SC with planar n-i-p architecture.

To find best suitable transport layers for CZTS absorber, the comparison of various ETLs and HTLs is performed on the basis of the conduction band offset (CBO) and valance band offset (VBO) values, respectively, that are form at interface as shown in Tables 1 and 2. The significance of selection of ETL and HTL by taking into account the vital role of band offset optimization is presented in various research works45,46,47,48.

This was the tactic applied to foresee the advantage of CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL for the CZTS absorber layer (Table 1). The good band tuning between CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS heterojunction is consistent with the researches35,36,37. Additionally, as CH3NH3SnI3 is usually p-type doped, we found it viable to treat it as an HTL.

For ETL, as the bandgap value and electron affinity of CdS material provides suitable band alignment with the CZTS absorber layer, CdS is chosen as the layer connecting absorber to consecutive ETLs. Moreover, Wessendorf et al. experimentally reported CdS as a strong hysteresis suppressant, easily processable low cost ETL exhibiting higher electron mobility72. Furthermore, Dehghan et al. demonstrated that ZnO offers high electron mobility and consequently a higher electrical conductivity, wide bandgap, and easy, cheap fabrication technique73. AZO material is also known to possess high quality, low resistive properties through many research studies. In addition to all this, CdS/ZnO/AZO provide suitable band offset with CZTS absorber for easy collection of electrons (Table 2). This is also confirmed by the researches conducted by Cantas et al., Perlikowski et al., Mutiari et al., and Routray et al.38,39,40,41. Hence, these layers are selected in SC device under investigation. The SC design and its band structure formation is presented in Fig. 1(a) and (b), respectively.

Finally, the parameters pertaining to each layer are carefully set to ensure that they are within the experimentally achievable limits, and are presented in Table 3. Thus, the proposed SC configuration can also be experimentally realizable.

The simulation of proposed SC was performed using the Solar Capacitance Simulator (SCAPS) software developed by University of Gent, Belgium. SCAPS software obtains performance characteristics of SC like its quantum efficiency, current density-voltage (J-V) curve, energy band alignment, etc. by solving Poisson’s Eq. (1) along with continuity equation for electrons (2) and for holes (3). These equations form the main principle of algorithm behind calculation of Voc, Jsc, FF and PCE for designed SC device7,46,74,75.

Here, Jp, Jn, G(x), q, Ψ, p(x), pt(x), n(x), nt(x), Rn(x), Rp(x), NA−(x) and ND+(x) denotes the hole current density, electron current density, generation rate, electronic charge, electrostatic potential, concentration of free holes, concentration of trapped holes, concentration of free electrons, concentration of trapped electrons, electron recombination rate, hole recombination rate, ionized acceptor concentration and ionized donor concentration, respectively. x denotes thickness of SC7,46,74,75.

The SC characteristics were simulated under AM 1.5 solar spectrum with incident power density of 1000 W/m2 at room temperature (300 K). The experimentally realizable parameters used in simulation are adopted from the standard literature7,76,77,78,79,80,81,82 and are reported in Table 3. During the SC designing process, the value of series resistance Rseries is held 5.8 Ω cm2, and the value of shunt resistance Rshunt is kept 2.2 × 104 Ω cm2 as reported by Gershon et al.83. In this study, we have set the experimentally observed magnitude of the diffusion length of charge carriers in CZTS material. Electron and hole diffusion length is found to be 0.3 μm84. In addition to this, the lowest value of certified defect density of CZTS layer was 1013 cm-3. Thus, we simulated the CZTS layer with the value to 1015 cm-3 to ensure easy fabrication and resulting low-cost scalable production.

Diffusion length is controlled by defect energy. After inserting practical values of defect density and diffusion length (or indirectly, the defect energy), the exact experimental values of the electron and hole capture cross-section were obtained7. The electron capture cross-section σe came out to be 2.8 × 10–13 cm2 and the hole capture cross-section σh values 7 × 10–14 cm2. It is ensured that the values satisfy the three formulas as mentioned in the Eqs. (4), (5) and (6).

where, τn, p, σn, p, Nt and vth are the lifetime of charge carriers, capture cross section of charge carriers, the absorber layer’s defect density, and velocity of charge carriers, D is the diffusion coefficient and LD is the diffusion length of charge carriers, q is the charge of an electron, T is the temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and µ is the charge carrier mobility. The values are well in match with the values of parameters as reported by Haddout et al.85. Similarly, the experimental carrier capture cross section is manipulated for CH3NH3SnI3 by Patel in his previous work7.

Along with discrete energy levels of defects, SCAPS software can also simulate defects which have special distribution such as gaussian distribution within the bandgap74. The parametric constant: Gauβ width parameter (\({w}_{G}\)) have default value of 6.0. Gaussian shape of energetic distribution of defects is then, set in the range from \({E}_{t}-\frac{{w}_{G}}{2}{\:E}_{C}\) to \({E}_{t}+\frac{{w}_{G}}{2}{\:E}_{C}\), where \({E}_{t}\) and\({\:E}_{C}\) denote energy level of trap state and characteristic energy, respectively. The Gaussian defect density \({N}_{t}\left(E\right)\), has the pattern as depicted by the Eq. (7),

where \({N}_{Peak}\) denote energetic density of defects at peak of Gaussian distribution. Hence, total Gaussian defect density \({N}_{Total}\) integrated over all the energies has value as shown in Eq. (8).

Electrode also plays an important role in smooth transfer of electrons/holes from ETL/HTL towards charge collecting terminal86. For easy carrier transportation, the electrode material must be selected such that it creates a low resistance contact or an Ohmic contact at its junction with ETL or HTL7,87. It also generates a charge-separating electric field at the electrode/semiconductor interface, which further encourages efficient charge collection87. Furthermore, the recombination losses at electrode/semiconductor interface are highly reduced due to Ohmic contact. In our case, since the SC has an n-i-p configuration, the back contact electrode will be in contact with the CH3NH3SnI3 HTL. To form an Ohmic contact at electrode/CH3NH3SnI3 interface, the work function of electrode (φe) must be greater than the work function of HTL CH3NH3SnI3 (φCH3NH3SnI3 = 4.75 eV)88. On this basis, the back contact electrode material selected for the study is platinum as it offers a metal work function of 5.65 eV, which is greater than φCH3NH3SnI389. Platinum has face-centered cubic (fcc) structure with lattice constant of 3.92 Å. Platinum is also chosen because it offers high electrical conductivity and stability, high catalytic activity, along with chemical inertness and resistance to oxidation. It is also compatible and provides excellent adhesion with perovskite material90.

The absorption profiles for CH3NH3SnI3, CZTS, CdS, ZnO, and AZO containing absorption coefficients as a function of incident wavelength are derived from the respective researches91,92,93,94,95. To make the SC close to the practical device, interface defects are also added internally. The SC interface parameters are presented in the Table 4.

Results and discussion

Charge carrier concentration plays a significant role in deciding the merit of HTL layer. Moreover, the property which distinguishes the chosen HTL CH3NH3SnI3 from other HTLs is that CH3NH3SnI3 undergoes spontaneous oxidation process. Hence, the charge carrier concentration within the layer increases spontaneously. Due to the known fact that charge carrier concentration in CH3NH3SnI3 rises above 1021 cm− 3 spontaneously with time26, the effect of this self-doping phenomenon on SC performance is studied due to variation in HTL charge carrier concentration from 1014 cm− 3 to 1022 cm− 3.

At higher doping concentrations, above 1022 cm− 3, the semiconductor CH3NH3SnI3 might become degenerate. In this case, myriad doped atoms become so close neighbors of each other that they form continuous band of acceptor atoms. Takahashi et al. studied the change in transport properties due to spontaneous doping in CH3NH3SnI3 and revealed that at high doping concentration, the material becomes degenerate semiconductor and doesn’t transform into a semi-metal96.

Device performance as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Figure 2 shows the variation of device performance parameters with HTL carrier concentration. Its values are showing appreciable increment with rising amount of carrier concentration. Now, the equation \(\sigma\:=ne\mu\:\) governs increment in the conductivity (\(\sigma\:\)) of the layer with rise in carrier concentration. This is in agreement with the observation obtained in the case of SC under study as seen in the Fig. 3. Moreover, increase in conductivity with self-doping of CH3NH3SnI3 is experimentally observed by Takahashi et al.96. Figure 3 presents increment in total conductance of SC as a result of HTL charge carrier concentration. As the layer conductivity is defined as the variation in carrier current density (\({J}_{sc}\)) per electric field (\(E\)) according to the Ohm’s law \(\sigma\:={J}_{sc}/E\), the current density rises with increasing conductivity for a fixed value of electric field, as shown in Fig. 2.

An SC gradually approaches the equilibrium state in which the drift and diffusion phenomenon are equal and opposite driving forces for the charge carriers in SC. During this process, there is variation in the electric and chemical potential within the device. Once the equilibrium state is reached, the change in the electric potential equals the change in the chemical potential which is equal to the magnitude of voltage created in the device97. Increasing the doping concentration in HTL layer increases the chemical potential in the SC device. This in turn increases the change in electric potential during attainment of equilibrium and finally increases the voltage (\({V}_{oc}\)) developed across the SC as observed in Fig. 2. This further increases the kinetic energy (\(E\)) of charge carriers in the SC according to the equation \(E=e{V}_{oc}\). Increase in charge transport can also be interpreted as the result of electric field increment due to rise in the voltage. This owes to the direct correlation between electric field and potential (\(V\)) given by the fundamental formula in electrodynamics, \(V=Ed\).

Increase in charge carrier concentration in layer results in decrease in the series (sheet) resistance as experimentally demonstrated and confirmed by Basher et al.98. And, decrease in series resistance consequently rises the value of FF2,3,4,5,6,7. Hence, with increase in charge carrier concentration, the FF value is enhanced as seen in Fig. 2.

Since PCE is directly related to the \({J}_{sc}\), \({V}_{oc}\) and FF according to the Eq. (9),

where Pin is the power of incident solar radiations46, increase in all the parameters ultimately results in improved PCE as confirmed by Fig. 2.

Total capacitance as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Capacitance (C) is given by the Eq. (10), where k, ε0 and d are dielectric constant, electrical permittivity of free space and width of depletion region in SC, respectively99.

In this study, the increase in capacitance with self-doped charge carrier concentration in HTL is evident from Fig. 4. Capacitance of SC can also be increased by shortening perovskite layer or reducing SC thickness. To reduce the SC thickness, if we remove perovskite (semiconductor) HTL and directly connect absorber to metal electrode which collects only holes, it may further enhance conductivity and capacitance in SC. But, due to small bandgap in metals, a large band offset will get generated at absorber/metal electrode interface. This will disturb the band alignment and will lead to high interfacial recombination. Hence, the efficiency of SC device will reduce. Study on such SC having configuration: Mo/CZTS/CdS/ZnO is performed earlier by Schubert et al.42. Their SC achieved efficiency of 4.1% experimentally. Katagiri et al. developed SC: Mo/CZTS/CdS/ZnO: Al43 by implementing similar tactics. This SC yielded efficiency of 6.77%. Hence, we have used CH3NH3SnI3 as HTL for optimized band alignment between absorber and hole-collecting metal electrode. Thus, the proposed SC yields high PCE.

Band alignment as a function of HTL carrier concentration

To further investigate, the analysis of effect of increase in HTL carrier concentration on band alignment of SC is performed. Figure 5 demonstrates evolution of conduction and valance band structure as a function of charge carrier concentration in HTL. It can be observed that there is shift.

in structure of conduction and valance band from a spike to a cliff at HTL/absorber interface with increase in HTL carrier concentration. As a consequence, the energy barrier for easy transport of holes from valance band of absorber layer to HTL layer is reduced. Thus, efficiency in collection of holes at the back contact rises with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration.

Similarly, evolution of conduction band structure at HTL/absorber interface benefits electron transport as well. With increase in HTL charge carrier concentration, there is increase in energy barrier for electrons in absorber layer to move towards the HTL as observed in Fig. 5. This efficiently restricts the back flow of electrons towards HTL. Figure 6 representing electron current density as a function of HTL carrier concentration confirms the same. There is noticeable decrement in electron current density that flows towards HTL from the absorber layer with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration. Hence, a greater number of electrons are promoted towards the ETL and efficiency of SC is enhanced with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration.

Variation in acceptor charge concentration may lead to change in bandgap of CH3NH3SnI3. However, the rise/fall and exact variation in bandgap depends on material and its synthesis process. Hence, software can’t predict this variation theoretically. Thus, this data may be explored independently during experimental realization of proposed SC.

Quasi Fermi levels as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Taking note of variation in quasi Fermi levels with rise in HTL charge carrier concentration, Fig. 7 is designed. From Fig. 7, it is clearly seen that there is increase in difference between the energies pertaining to Fermi levels of electrons (EFn) and holes (EFp) with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration.

Recombination rate as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Recombination profile is also an important aspect that impacts SC yield. Hence, recombination pattern is recorded spatially in bulk SC (Fig. 8), as a whole in bulk SC (Fig. 9), at back contact (Fig. 10), and combining recombination in bulk and at back & front contact to obtain total recombination (Fig. 11) for the SC under study.

Bulk recombination rate as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Figure 8 is presented to understand spatial variation of recombination rate in bulk SC. From Fig. 8, the interpretation one can make is that in almost entire SC except the HTL/absorber interface and the back contact, the recombination is very less and constant under variation in HTL charge carrier concentration. Secondly, the diagram clearly depicts variation in HTL/absorber interfacial recombination rate pattern. Thus, Fig. 8 confirms that there is slight increase in interfacial recombination rate until HTL carrier concentration reaches up to 1022 cm− 3.

Figure 9 collectively demonstrates the value of total recombination current density within the bulk SC as a function of HTL charge carrier concentration. According to the Fig. 9, the bulk recombination current density increases very slightly until the HTL charge carrier concentration reaches up to 1017 cm− 3, after which there is gradual decrement in bulk recombination current density up to concentration 1021 cm− 3. After 1021 cm− 3, recombination current density falls dramatically.

To understand the variation in bulk recombination rate in SC, the analysis of accumulation profile of electrons and holes in bulk SC is useful. The rise or fall in bulk recombination rate depends on the number of recombination centers present in bulk SC. Generally, the electrons act as recombination centers in HTL and in absorber/HTL interface, whereas holes act as recombination centers in ETL and in absorber/ETL interface21,100,101. Hence, spatial pattern of electron and hole distribution within SC structure is necessary to understand bulk recombination phenomenon with clarity. Figures 10 and 11 demonstrates electron and hole density spatially as a function of HTL charge carrier concentration.

As confirmed by Fig. 10, there is exponential decrement in electron density at HTL/absorber interface as a result of rise in HTL charge carrier concentration. This is the evidence of reduction in number of recombination sites for holes travelling from absorber layer to HTL via the HTL/absorber interface. Moreover, the number of electrons entering HTL also undergoes reduction with increment in HTL charge carrier concentration as observed from the Fig. 10. Thus, with increase in HTL carrier concentration, only a smaller number of counter charges (electrons) are left in the HTL for the concerned charge carrier (holes) to recombine with. The generation of strong chemical and electric potential in SC with increase in HTL carrier concentration, as inferred from Fig. 2, is responsible to efficiently drive the electrons away from HTL and towards ETL. Thus, after calculating hole capture cross-section and trapping rate (charge occupation/accumulation rate) data as a function of HTL charge carrier concentration, the decreasing graph is observed. Consequently, this will reduce the hole capture cross-section and trapping rate. Also, the carrier diffusion length increases and charge collection become efficient102. This explains the reduction in bulk recombination current density with increase in HTL carrier concentration as seen in Fig. 9.

Similar analysis can be performed from the spatial variation of hole density as a function of HTL charge carrier concentration presented in Fig. 11. Interpretation one can derive from Fig. 11 is that there is exponential increment in holes density at the HTL/absorber interface cite. Less decrement in hole density at interface with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration confirms presence of lesser recombination cites at interface and that the lesser number of holes are undergoing capture (trapping) due to interfacial recombination, as explained using the Fig. 10. Thus, efficient transportation of holes from absorber layer to HTL via interface is seen to take place with increment in HTL carrier concentration. Thus, Figs. 11 and 12 provide vivid explanation for decrement in the bulk total recombination current density in SC as a function of increasing HTL charge carrier concentration.

Contact recombination current density as a function of HTL carrier concentration

Apart from the bulk recombination rate, the other type of recombination rate that persists in SC and contributes to total recombination rate is the recombination rate at back and front contact terminals of SC. Voc is mainly sensitive to the contact recombination103. Paul et al. performed Voc analysis as a function of wavelength to experimentally demonstrate the impact of back-contact recombination rate on SC performance. Decreasing the contact recombination is also a key to increase SC yield103,104,105,106,107,108,109. Hence, the variation of back-contact recombination current density is analyzed for the SC under study as a function of HTL charge carrier concentration and is presented in Fig. 12. It can be observed that there is rapid decrement in bank contact recombination current density with increase in HTL carrier concentration. This creates condition favorable for higher SC device PCE. This may be due to increment in the diode factor and quasi-Fermi level splitting as explained by Wang et al.109.

Total recombination rate as a function of HTL carrier concentration

The effect of bulk and contact recombination rates can be cumulatively analyzed using the total recombination rate in SC. The total recombination current density profile for SC under study is demonstrated using Fig. 13. Thus, with increase in HTL charge carrier concentration, there is decrement in overall recombination rate in SC. Carrier concentration was also seen to reduce the density of trap states as per the study conducted by Yang et al.110. The reduction of total recombination in SC is because of better extraction of the holes from CZTS layer to HTL. Holes spend less time in CZTS absorber layer, where holes and electrons are equally generated and where the chances of recombination are very high. Hence, eased hole extraction process favors high device response with increasing carrier concentration of HTL layer and total current is increased as seen in Fig. 2.

Possible new application of Sn-based perovskite in SC

Thus, finally simulating the SC with intermediate HTL carrier concentration of 1021 cm-3, the obtained resultant values of SC performance parameters are Jsc of 31.503 mA/cm-3, Voc of 0.9642 V, FF of 64.64% and PCE of 19.63%, which is considerably higher as compared to other reported CZTS-based SCs44,75. The findings presented in this paper are consistent with the similar researches on CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS heterojunction37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. Table 5 compares the result produced in this paper with the performance of previously researched CZTS-based SCs with various other HTLs.

One can conclude from the Table 5 that the results produced in this paper can potentially advance the current CZTS-based SCs. The self-cleaning transparent conductive coatings are largely looked upon as the potential solution to prevent SC degradation. From the 3-months of outdoor testing, Bernard et al. demonstrated that the SC coated with self-cleaning film recovered > 95% PCE, whereas the SC without coating underwent PCE degradation to 80–90% PCE119. In the practical working conditions, the transparent self-cleaning film coated SC of Xu et al. also maintained 95.8% PCE, which was 1.7 times larger than the degraded PCE of SC that wasn’t coated120. Moreover, Aktas et al. has presented detailed information concerning various strategies in which researchers retained SC PCE with time20. Introducing graphene in PSC structure can also enhance its stability121. Thus, the PCE decay can be largely be prevented by the application of SC self-cleaning coating technology and other compositional strategies. In this scenario, synergy of all these technologies with the technology introduced in this paper may completely compensate the destructive impact of the degrading factors: dust, heat, light and moisture, and may possibly enhance the device PCE further with time.

In the absence of this study, scientists were trying hard to stop the spontaneous self-doping phenomenon to make CH3NH3SnI3 a better absorber material10,20,21,24,25,26,27. After this work, the direction and intention of future research endeavors may be shifted towards using CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL and encouraging its spontaneous self-doping property rather than preventing it. This can possibly make next-generation SCs tackle all its degradation factors by itself, and further show improvement in performance spontaneously.

Such devices with perovskite HTL film are meant to possess a planar n-i-p architecture to avoid strong photon absorption in HTL by perovskite material. The planar n-i-p architecture of SC also affects the performance of SC device122. Moreover, CZTS requires a high annealing temperature during deposition. Hence, while experimentally realizing this SC configuration: CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS/CdS/ZnO/AZO, if CZTS is deposited above the perovskite HTL, CH3NH3SnI3 will undergo self-oxidation during SC synthesis process itself. This will lead to its degradation. To avoid it, this SC configuration can be experimentally realized by depositing ZnO, CdS and CZTS sequentially on top of AZO-coated glass. Lastly, the CZTS can be covered with CH3NH3SnI3. Hence, the proposed SC can be feasibly fabricated. On further optimizing the absorber layer, this prototype solar cell points towards highly-stable high-efficiency device as investigated in our recent research49.

Conclusion

A prototype SC having CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL is investigated for the first time in this paper. To understand the effect of unique spontaneous self-doping property of CH3NH3SnI3 on SC performance, the SC configuration: CH3NH3SnI3/CZTS/CdS/ZnO/AZO is analysed. With increase in HTL charge carrier concentration, we observed noticeable improvement in the performance of SC. This was due to increment in total conductance and electric field, electric and chemical potential, diffusion coefficient, diffusion length and total capacitance in SC. Moreover, there was improvisation of band alignment leading to increase in hole current density and decrease in electron current density towards HTL. Furthermore, there was increment in difference between electron and hole Fermi levels, and decrement in series resistance, bulk total recombination current density, back contact recombination current density and total recombination current density. Reduction in total recombination current density was due to decrease in recombination centers i.e. electron density and increment in hole density in HTL and at HTL/absorber interface. This reduced hole capture cross-section and trapping rate in HTL. Thus, increase in HTL charge carrier concentration favours enhancement in SC yield. Since CH3NH3SnI3 provides the spontaneous rise in carrier concentration with time, utilization of CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL in the SC devices may provide a viable path for the high-efficiency, stable, eco-friendly as well as cost-friendly solar cells, whose efficiency possibly rises with operation time. Since the air atmosphere cause increment in the rate of spontaneous self-doping in CH3NH3SnI3, it can also mark a positive impact and contribute to enhance PCE of SC when SC system is embedded with CH3NH3SnI3 as an HTL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kannan, N. & Vakeesan, D. Solar energy for future world: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 62, 1092–1105 (2016).

Jha, D. et al. Optical simulations and optimization of highly efficient GaAs based quantum dot solar cell. Opt. Commun. 523, 128717 (2022).

Krishna, R. V. et al. Effect of electrical parameters on lead-based perovskite solar cell for high-efficiency performance. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54, 513 (2022).

Mahapatra, B., Krishna, R. V. & Patel, P. K. Design and optimization of CuSCN/CH3NH3PbI3/TiO2 perovskite solar cell for efficient performance. Opt. Commun. 504, 127496 (2022).

Katariya, A. et al. Optimization of ETM and HTM layer on NFA based BHJ-organic solar cell for high efficiency performance. Optik 245, 167717 (2021).

Krishna, R. V. et al. Device simulation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cell with high efficiency. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 2352. No. 1 (AIP Publishing, 2021).

Patel, P. K. Device simulation of highly efficient eco-friendly CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite solar cell. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–11 (2021).

Pascual, J. et al. Origin of Sn (II) oxidation in tin halide perovskites. Mater. Adv. 1(5), 1066–1070 (2020).

Rühle, S. Tabulated values of the Shockley–Queisser limit for single junction solar cells. Sol. Energy 130, 139–147 (2016).

Nakamura, T. et al. Sn (IV)-free tin perovskite films realized by in situ sn (0) nanoparticle treatment of the precursor solution. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1–8 (2020).

McMeekin, D. P. et al. Intermediate-phase engineering via dimethylammonium cation additive for stable perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 1–11 (2022).

Liu, X., et al. Perovskite solar cells based on spiro-OMeTAD stabilized with an alkylthiol additive. Nat. Photon. 17(1), 96–105 (2023).

Christians, J. A., Miranda Herrera, P. A. & Kamat, P. V. Transformation of the excited state and photovoltaic efficiency of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite upon controlled exposure to humidified air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137(4), 1530–1538 (2015).

Aristidou, N. et al. Fast oxygen diffusion and iodide defects mediate oxygen-induced degradation of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 15218 (2017).

Snaith, H. J. Present status and future prospects of perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Mater. 17(5), 372–376 (2018).

Christians, J. A. et al. Tailored interfaces of unencapsulated perovskite solar cells for > 1,000 hour operational stability. Nat. Energy 3(1), 68–74 (2018).

Aktas, E. et al. Challenges and strategies toward long-term stability of lead-free tin-based perovskite solar cells. Commun. Mater. 3(1), 1–14 (2022).

Saidaminov, M. I. et al. Conventional solvent oxidizes Sn (II) in perovskite inks. ACS Energy Lett. 5(4), 1153–1155 (2020).

Grätzel, M. The light and shade of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 13.9 (2014): 838–842 .

Zhao, Y. & Zhu, K. Solution chemistry engineering toward high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5(23), 4175–4186 (2014).

Correa-Baena, J. P. et al. The rapid evolution of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 10(3), 710–727 (2017).

Zhang, Z. et al. Big data driven perovskite solar cell stability analysis. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 7639 (2022).

Duan, L. et al. Stability challenges for the commercialization of perovskite–silicon tandem solar cells. Nat. Reviews Mater. : 1–21. (2023).

Lanzetta, L. et al. Degradation mechanism of hybrid tin-based perovskite solar cells and the critical role of tin (IV) iodide. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1–11 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Efficient and stable tin perovskite solar cells enabled by amorphous-polycrystalline structure. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1–7 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. A holistic approach to interface stabilization for efficient perovskite solar modules with over 2,000-hour operational stability. Nat. Energy 5(8), 596–604 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. In situ growth of graphene on both sides of a Cu–Ni alloy electrode for perovskite solar cells with improved stability. Nat. Energy 1–8. (2022).

Khadka, D. B. et al. Advancing efficiency and stability of lead, tin, and lead/tin perovskite solar cells: Strategies and perspectives. Solar RRL 7(21), 2300535 (2023).

Sharif, R. et al. A comprehensive review of the current progresses and material advances in perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale Adv. 5(15), 3803–3833 (2023).

Kirchartz, T. & Cahen, D. Minimum doping densities for p–n junctions. Nat. Energy 5(12), 973–975 (2020).

Minemoto, T. & Murata, M. Device modeling of perovskite solar cells based on structural similarity with thin film inorganic semiconductor solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 116, 5 (2014).

Minemoto, T. & Murata, M. Impact of work function of back contact of perovskite solar cells without hole transport material analyzed by device simulation. Curr. Appl. Phys. 14(11), 1428–1433 (2014).

Minemoto, T. et al. Theoretical analysis of the effect of conduction band offset of window/CIS layers on performance of CIS solar cells using device simulation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 67, 1–4 (2001).

Baig, F. et al. Numerical analysis a guide to improve the efficiency of experimentally designed solar cell. Appl. Phys. A 124, 1–8 (2018).

Piñón Reyes, A.C., et al. Study of a lead-free perovskite solar cell using CZTS as HTL to achieve a 20% PCE by SCAPS-1D simulation. Micromachines 12(12), 1508 (2021).

Islam, M. A., Alamgir, B., Chowdhury, S. I. & Billah, S. M. B. Lead-free organic inorganic halide perovskite solar cell with over 30% efficiency. J. Ovonic Res. 18, 3 (2022).

Mohanty, I., Mangal, S. & Singh, U. P. Defect optimization of CZTS/MASnI3 Heterojunction Solar Cell Yielding 30.8% efficiency. J. Electron. Mater. 1–9. (2023).

Cantas, A. et al. Importance of CdS buffer layer thickness on Cu2ZnSnS4-based solar cell efficiency. J. Phys. D 51(27), 275501 (2018).

Perlikowski, I. et al. Structural properties and electrical characteristics of pn junctions based on kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 layers for thin-film solar cells. Energies 14(16), 5182 (2021).

Mutiari, A. et al. Design and implementation of an ultrathin dielectric/metal/dielectric transparent electrode for Cu2ZnSnS4 thin-film photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 230, 111247 (2021).

Routray, S. Boosting the efficiency of kesterite solar cell: Use of ag mixed Cu2ZnSnS4 intermediate thin film layer. Phys. Status Solidi A Appl. Mater. Sci. 219, 8 (2022).

Schubert, B.-A., et al. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film solar cells by fast coevaporation. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 19(1), 93–96 (2011).

Katagiri, H. et al. Enhanced conversion efficiencies of Cu2ZnSnS4-based thin film solar cells by using preferential etching technique. Appl. Phys. Express 1(4), 041201 (2008).

Kumar, A. Efficiency enhancement of CZTS solar cells using structural engineering. Superlattices Microstruct. 153, 106872 (2021).

Minemoto, T. & Murata, M. Theoretical analysis on effect of band offsets in perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 133, 8–14 (2015).

Bagade, S. S. et al. Impact of band alignment at interfaces in perovskite-based solar cell devices. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Bagade, S. et al. Establishment of justified parameter optimization sequence for obtaining maximum solar cell efficiency. Phys. Scr. 98(10), 105972 (2023).

Bagade, S. S. & Patel, P. K. Insight into conduction band density of states at c-Si/TiO2 interface for efficient heterojunction solar cell. Phys. Scr. 98(10), 105958 (2023).

Bagade, S. S., Malik, M. M. & Patel, P. K. The Charm of entwining two major competitors CZTS & CH3NH3SnI3 to feasibly explore photovoltaic world beyond Shockley-Queisser limit. Surf. Interfaces 104020 (2024).

Alam, I., Mollick, R. & Ashraf, M. A. Numerical simulation of Cs2AgBiBr6-based perovskite solar cell with ZnO nanorod and P3HT as the charge transport layers. Phys. B Condens. Matter 618, 413187 (2021).

Hosseini, S. et al. Investigating the effect of non-ideal conditions on the performance of a planar CH3NH3PbI3-based perovskite solar cell through SCAPS-1D simulation Heliyon 8(11) (2022).

Kumari, P. et al. Enhanced photovoltaic performance of PEDOT: PSS/Si heterojunction solar cell with ZnO BSF layer: A simulation study using SCAPS-1D. Silicon 15(5), 2099–2112 (2023).

Medina, J. C. Z. et al. Numerical simulation and performance optimization of a solar cell based on WO3/CdTe heterostructure using NiO as HTL layer by SCAPS 1D. Coatings 13(8), 1436 (2023).

Nithya, K. S. & Sudheer, K. S. Device modelling of non-fullerene organic solar cell with inorganic CuI hole transport layer using SCAPS 1-D. Optik 217, 164790 (2020).

Abdelfatah, M. et al. SCAPS simulation of novel inorganic ZrS2/CuO heterojunction solar cells. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4553 (2023).

Ravishankar, S. et al. Multilayer capacitances: How selective contacts affect capacitance measurements of perovskite solar cells. PRX Energy 1(1), 013003 (2022).

Obare, N. et al. Numerical study of copper antimony sulphide (CuSbS2) solar cell by SCAPS-1D. Heliyon 10(5) (2024).

Fentahun, D. A., Tyagi, A. & Kar, K. K.. Numerically investigating the AZO/Cu2O heterojunction solar cell using ZnO/CdS buffer layer. Optik 228, 166228 (2021).

Zhao, J. et al. Band alignment strategy for printable triple mesoscopic perovskite solar cells with enhanced photovoltage. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2(3), 2034–2042 (2019).

Rono, N. et al. Simulation of the photovoltaic performance of a perovskite solar cell based on methylammonium lead iodide. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54(5), 317 (2022).

Chowdhury, M. S. et al. Effect of deep-level defect density of the absorber layer and n/i interface in perovskite solar cells by SCAPS-1D. Results Phys. 16, 102839 (2020).

Dasgupta, U., Bera, A. & Pal, A. J. Band diagram of heterojunction solar cells through scanning tunneling spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 2(3), 582–591 (2017).

Cao, F., Wang, M. & Li, L. Graded energy band engineering for efficient perovskite solar cells. Nano Select 1(2), 152–168 (2020).

Korir, B. K., Kibet, J. K. & Ngari, S. M.. Computational simulation of a highly efficient hole transport-free dye-sensitized solar cell based on titanium oxide (TiO2) and zinc oxysulfide (ZnOS) electron transport layers. J. Electron. Mater. 50(12), 7259–7274 (2021).

Naureen et al. A simulation study of quantum dot solar cells using two distinct ETL of WO3 and WS2. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55(6), 541 (2023).

Rahman, M. F. et al. Boosting efficiency above 30% of novel inorganic Ba3SbI3 perovskite solar cells with potential ZnS electron transport layer (ETL). Mater. Sci. Engi. B 300, 117073 (2024).

Hima, A., Khechekhouche, A. & Kemerchou, I. Enhancing of CH3NH3SnI3 based solar cell efficiency by ETL engineering. Int. J. Energy 5(1), 27 (2020).

Song, J. et al. Numerical simulation and performance optimization of all-inorganic CsGeI3 perovskite solar cells with stacked ETLs/C60 by SCAPS device simulation. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 108587 (2024).

Biswas, S. K. et al. A numerical approach to analysis of an environment-friendly Sn‐based perovskite solar cell with SnO2 buffer layer using SCAPS‐1D. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1, 4154962 (2023).

Rahmoune, A & Babahani, O. Numerical analysis of Al/Gr/ETL/MoS2/Sb2S3/Ni solar cell using non-toxic In2S3/SnS2/ZnSe electron transport layer. Optik 283, 170875 (2023).

Bagade, S. S. & Patel, P. K. A comprehensive review on potential of diffusion length enhancement to upraise perovskite solar cell performance. Phys. Scr. (2024).

Wessendorf, C. D. et al. CdS as electron transport layer for low-hysteresis perovskite solar cells. Solar RRL 2(5), 1800056 (2018).

Dehghan, M. & Behjat, A. Deposition of zinc oxide as an electron transport layer in planar perovskite solar cells by spray and SILAR methods comparable with spin coating. RSC Adv. 9(36), 20917–20924 (2019).

Burgelman, M., Decock, K., Niemegeers, A., Verschraegen, J. & Degrave, S. SCAPS manual, February (2016).

Raoui, Y. et al. Performance analysis of MAPbI3 based perovskite solar cells employing diverse charge selective contacts: Simulation study. Sol. Energy 193, 948–955 (2019).

Patel, M. & Ray, A. Enhancement of output performance of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film solar cells—a numerical simulation approach and comparison to experiments. Phys. B Condens. Matter 407(21), 4391–4397 (2012).

Saha, U. & Kawsar, M. A. Proposition and computational analysis of a kesterite/kesterite tandem solar cell with enhanced efficiency. RSC Adv. 7(8), 4806–4814 (2017).

Saha, U. & Kawsar, M. A. Boosting the efficiency of single junction kesterite solar cell using Ag mixed Cu2ZnSnS4 active layer. RSC Adv. 8(9), 4905–4913. (2018).

Abdelkadir, A. A. et al. Numerical simulation and optimization of n-Al-ZnO/n-CdS/p-CZTSe/p-NiO(HTL)/Mo solar cell system using SCAPS-1D. Results Opt. 8, 100257 (2022).

Grimmeiss, H. G., Janzén, E. & Kullendorff, N. Electron capture cross-section in copper doped CdS. Solid State Commun. 35(9), 727–728 (1980).

Look, D. C. et al. Electrical properties of bulk ZnO. Solid State Commun. 105(6), 399–401 (1998).

Dalapati, G. K. et al. Impact of molybdenum out diffusion and interface quality on the performance of sputter grown CZTS based solar cells. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 1–12 (2017).

Gershon, T. et al. Photoluminescence characterization of a high-efficiency Cu2ZnSnS4 device. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 15 (2013).

Gokmen, T. Gunawan, O. & Mitzi, D. B. Minority carrier diffusion length extraction in Cu2ZnSn(Se,S)4 solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 114(11), 114511 (2013).

Haddout, A. et al. Understanding effects of defects in bulk Cu2ZnSnS4 absorber layer of kesterite solar cells. Sol. Energy 211, 301–311 (2020).

Jan, S. T. & Noman, M. Influence of layer thickness, defect density, doping concentration, interface defects, work function, working temperature and reflecting coating on lead-free perovskite solar cell. Sol. Energy 237, 29–43 (2022).

Nelson, J. A. The Physics of Solar Cells (World Scientific Publishing Company, 2003).

Sahoo, D., Karan, A. K. & Manik, N. B. Influence of SWCNT on the Electrical Behavior of an environmentally friendly CH3NH3SnI3 Perovskite-based Optoelectronic Schottky device. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5(4), 2203–2214 (2023).

Behrouznejad, F. et al. A study on utilizing different metals as the back contact of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 4(35), 13488–13498 (2016).

Mohebpour, M. A. et al. High performance of mixed halide perovskite solar cells: Role of halogen atom and plasmonic nanoparticles on the ideal current density of cell. Phys. E Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. 97, 282–289 (2018).

Sabetvand, R., Ghazi, M. E. & Izadifard, M. Studying temperature effects on electronic and optical properties of cubic CH3NH3SnI3 perovskite. J. Comput. Electron. 19, 70–79 (2020).

Bakr, N. A., Salman, S. A. & Sabreen, A. Hameed. Deposition and characterization of Cu2ZnSnS4 thin films for solar cell applications. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 13(6), 3379–3388 (2018).

Khashan, K. S. Synthesis, structure and optical properties of CdS nanoparticles prepared by chemical method. Eng. Technol. J. 31(1B), 39–48 (2013).

Borhani Zarandi, B. & Bioki, H. A. Effects of cobalt doping on optical properties of ZnO thin films deposited by sol–gel spin coating technique. J. Optoelectron. Nanostruct. 2(4), 33–44 (2017).

Hossain, S., Quaderi, G. D. A., Hussain, K. M. A. & Faruqe, T. Synthesis and characterization of Undoped and Aluminum Doped Zinc Oxide Thin films using Thermal Evaporation Method. Nuclear Sci. Appl. 27(1), 2 (2018).

Takahashi, Y. et al. Hall mobility in tin iodide perovskite CH3NH3SnI3: Evidence for a doped semiconductor. J. Solid State Chem. 205, 39–43 (2013).

Lipovšek, B. et al. Driving forces and charge-carrier separation in pn junction solar cells. AIP Adv. 9(5), 055026 (2019).

Basher, M. K. et al. Effect of doping profile on sheet resistance and contact resistance of monocrystalline silicon solar cells. Mater. Res. Express 6(8), 085510 (2019).

Alfaramawi, K. Correlation between electron mobility and static dielectric permittivity of n-InSb. Open. Phys. 13, 1 (2015).

Wang, J. Open-circuit voltage, fill factor, and heterojunction band offset in semiconductor diode solar cells. EcoMat 4.6 : e12263. (2022).

Foertig, A. et al. Charge carrier concentration and temperature dependent recombination in polymer-fullerene solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 5 (2009).

Hodes, G. & Kamat, P. V. Understanding the implication of carrier diffusion length in photovoltaic cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6(20), 4090–4092 (2015).

Paul, S. et al. Analysis of back-contact interface recombination in thin-film solar cells. IEEE J. Photovolt. 8(3), 871–878 (2018).

Hages, C. J. et al. Improved performance of Ge-alloyed CZTGeSSe thin‐film solar cells through control of elemental losses. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 23(3), 376–384 (2015).

Ponseca, S. Jr et al. Organometal halide perovskite solar cell materials rationalized: Ultrafast charge generation, high and microsecond-long balanced mobilities, and slow recombination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(14), 5189–5192 (2014).

Taguchi, M. et al. 24.7% record efficiency HIT solar cell on thin silicon wafer. IEEE J. Photovolt. 4(1), 96–99 (2013).

Todorov, T. K. et al. Beyond 11% efficiency: Characteristics of state-of‐the‐art Cu2ZnSn(S,Se)4 solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 3(1), 34–38 (2013).

Wang, W. et al. Device characteristics of CZTSSe thin-film solar cells with 12.6% efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 4(7), 1301465 (2014).

Wang, T. et al. Diode factor in solar cells with metastable defects and back contact recombination. Adv. Energy Mater. 12(44), 2202076 (2022).

Yang, Z. et al. Enhancing electron diffusion length in narrow-bandgap perovskites for efficient monolithic perovskite tandem solar cells. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 4498 (2019).

Momose, N. et al. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film solar cells utilizing sulfurization of metallic precursor prepared by simultaneous sputtering of metal targets. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50(1S2), 01BG09 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. Low-temperature processed electron collection layers of graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites in thin film perovskite solar cells. Nano Lett. 14(2), 724–730 (2014).

Ahmed, S. et al. A high efficiency electrodeposited Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cell. Adv. Energy Mater. 2(2), 253–259 (2012).

Sivathanu, V., Rajalingam, T. & Trupti Ranjan, L. Modelling of CZTS/ZnS/AZO solar cell for efficiency enhancement. In 2018 3rd International Conference on Microwave and Photonics (ICMAP) (IEEE, 2018).

Jhuma, F. A., Shaily, Akter, M. Z. & Rashid, M. J. Towards high-efficiency CZTS solar cell through buffer layer optimization. Mater. Renew. Sustain. Energy 8, 1–7 (2019).

Rahman, M. S. et al. Bilayer CZTS/Si absorber for obtaining highly efficient CZTS solar cell. Sol. Energy 230, 1189–1198 (2021).

Latrous, A. et al. Conduction band offset effect on the Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells performance. Ann. Chim. Sci. Matér. 45(6) (2021).

Vallisree, S. et al. Investigations of carrier transport mechanism and junction formation in Si/CZTS dual absorber solar cell technology. Appl. Phys. A 126, 1–10 (2020).

Bernard, A. R. et al. Dust settles, we don’t: The electrodynamic screen—A self-cleaning technology for concentrated solar power mirrors and photovoltaic panels. MRS Energy Sustain. 5, E12 (2018).

Xu, Q. et al. A new kind of transparent and self-cleaning film for solar cells. Nanoscale 8(41), 17747–17751 (2016).

Bagade, S. S. et al. Recent advancements in applications of graphene to attain next-level solar cells. C 9(3), 70 (2023).

Jan, S. T. & Noman, M. Analyzing the effect of planar and inverted structure architecture on the properties of MAGeI3 perovskite solar cells. Energy Technol. 11, 2300564 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Marc Burgelman (University of Gent) for providing the simulation software SCAPS.

Funding

No source of funding is available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sonal Santosh Bagade performed conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, visualization, and writing. Dr. Piyush K. Patel performed conceptualization, project administration, supervision and provided necessary resources. All authors performed formal analysis and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Statement

All participants have given written informed consent to participate in the study. This paper is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere. The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors. All authors have been personally and actively involved in substantial work leading to the paper, and will take public responsibility for its content.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bagade, S.S., Patel, P.K. Salutary impact of spontaneous oxidation in CH3NH3SnI3 on CZTS-based solar cell. Sci Rep 15, 3056 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74964-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74964-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Initial study on performance enhancement of using FeS2 back surface field and antireflective layers in CZTS solar cells

Discover Applied Sciences (2025)