Abstract

Prior research show that relative deprivation can decrease individuals’ psychological well-being. However, the underlying mechanism between relative deprivation and psychological well-being remains unclear. To explore the mediating effects of self-efficacy and self-control on the relationship between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. 426 undergraduate students submitted the online survey that assessed their psychological well-being, relative deprivation, self-efficacy and self-control. Students experienced high levels of psychological well-being, moderate to high levels of relative deprivation and moderate levels of self-efficacy and self-control. Parallel mediators of self-efficacy and self-control on the relationship between relative deprivation and psychological well-being were significant (each p < 0.01). This study explores the underlying mechanism between relative deprivation and psychological well-being by identifying the parallel mediators of self-efficacy and self-control. Effective interventions should be taken to alleviate students’ relative deprivation and promote their self-efficacy, self-control and psychological well-being during future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a global severe acute respiratory syndrome crisis that was first reported in December 20191. COVID-19 not only affects the physical and mental health of millions of people worldwide, but also forces leaders in politics, economy and education to take drastic strategies that impact how individuals interact and socialize. Several studies showed that, due to the switch to online learning, the spread of infection and social isolation, undergraduate students had a rise in mental health issues and symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression and sleep disorders) and experienced low levels of psychological well-being2,3,4. Most of the literature supports that psychological well-being has been confirmed as an important component for maintaining physical health and promoting learning performance in undergraduate students5. Previous studies have shown that psychological well-being has negative correlations with adverse physical status (e.g., allergies, obesity and alopecia), learning burnout, problem behaviors and dropout6,7.Therefore, understanding the influencing factors of psychological well-being for undergraduate students during high-stress periods is critical for educators, parents and students to understand current psychological conditions and prepare for future pandemics.

Relative deprivation is considered a subjective feeling of anger and resentment, when people or groups find their disadvantages, weakness and shortages through horizontal and vertical comparison with other outstanding people and groups8. Relative deprivation is composed of two dimensions: the cognitive dimension, in which individuals find their defects via upward social comparison9; and the emotional dimension, in which individuals’ perceived relative deprivation often includes feelings of anger, discontent and indignity10. As a basis for understanding individuals’ natural emotions and social interactions, relative deprivation significantly correlates with depressive symptoms, social exclusion, quality of life, moral disengagement, game addiction and disordered gambling in young adults11,12. It is believed that people’s feeling of relative deprivation is an important risk factor for numerous mental and physical health-related issues due to perceived disparities13. However, as prior studies have concentrated on the direct relationship between relative deprivation and mental and physical health, the mediation mechanism remains unclear. Further study is necessary to explore the mediating variables and reveal the underlying mechanism between relative deprivation and psychological well-being in undergraduate students.

Self-efficacy is defined as an individual’s beliefs in his or her ability to create the desired outcomes through his or her interaction with the environment and society14. As an efficacy cognitive expectation, self-efficacy has certain effects on people’s emotions and actions in coping with difficult situations, which could help in the comprehension of individuals’ choices, motivation, judgments and behaviors in impending conditions15,16. Several studies show that self-efficacy plays an important role in managing stress and frustration and promoting the engagement, persistence, achievement, well-being and mental health of undergraduate students17,18. Students experiencing high levels of self-efficacy may have more positive energy and resources to decrease the negative influences of stress, which ultimately improve their learning performance and mental health19.To date, few studies have explored the relationships among relative deprivation, self-efficacy and the psychological well-being of undergraduate students.

Self-control refers to one’s capacity to monitor emotions and behaviors that guarantee one’s thoughts and behaviors conforming with the norms of social morality and attaining established goals20,21. As an inhibition of goal-inconsistent impulses, self-control contains executive dimensions (e.g., healthy habits and focusing on the work) and reactive dimensions (e.g., impulse control and resisting temptation)22. A literature review shows that high self-control is beneficial for psychological well-being, engagement in health promotion and prosocial behaviors23,24. Individuals with high self-control can objectively evaluate the environment, develop a clear career program, promote harmonious social relationships, have good professional achievements, and experience high levels of well-being and positive emotions25,26. Moreover, self-control is a significant factor that accounts for individuals’ physical and mental impairments related to stress, such as posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic job stress27,28. Although numerous studies have tested the correlations between self-control and psychological well-being and external behaviors, the association between self-control and relative deprivation remains unclear. Furthermore, the function of self-control on the relationship between relative deprivation and psychological well-being needs to be studied to clarify the internal mechanism of the relationship.

Psychological stress system theory shows that psychosocial stressors can cause psychological, behavioral and physical changes, while self-efficacy and personality are important factors that mediating this process29. In the study, relative deprivation is proposed to impact psychological changes via psychosocial stress springing from upward social comparisons30. Psychological well-being is considered as a psychological change brought on by subjective perception of being at a comparative disadvantage31. Studies demonstrated that relative deprivation has a strong negative association with psychological well-being32,33. Self-efficacy is a cognitive process that one learn new knowledge and skills to promote his/her future events. Enhancing self-efficacy can alleviate stress-related outcomes and improve quality of life for individuals living with stress34. Therefore, in this study, self-efficacy was proposed as a mediating variable and its mediating effect in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being was tested to reveal the underlying mechanism of this association. Self-control refers to generalized beliefs that thoughts, feelings and actions affect final goals. Negative correlation was found between stress and self-control27. While, self-control is positively correlated with psychological well-being25. Thus, self-control was proposed as another mediator in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being.

In the study, two hypotheses were examined. First, we assumed that students experienced low levels of psychological well-being, self-efficacy and self-control and high level of relative deprivation. Second, we assumed that self-efficacy and self-control would be parallel mediators on the relationship between relative deprivation and psychological well-being, higher relative deprivation would be correlated with lower self-efficacy and self-control, and lower self-efficacy and self-control would be positively associated with lower psychological well-being.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out between April 2022 and September 2022 and involved Chinese undergraduate students. A convenience sampling method was used to recruit student participants. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) undergraduate student; (2) Chinese; and (3) proficient in using computer and communication software, such as WeChat and QQ. Students with psychosis were excluded from the study.

Procedure

After a public announcement to all six college and university students, an online and offline recruitment methods were used to recruit student participants. Students who had interested in the study can screen a QR code to assess the online questionnaires. There were two components of the survey: explaining statement and the questionnaires. Students who submitted the questionnaire were considered as agreeing to participate the study.

Measurements

A socio-demographic questionnaire, the Economic Relative Deprivation Scale (ERDS), the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES), the Self-Control Scale (SCS) and the psychological well-being subscale of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) were used to collect data on students’ socio-demographic characteristics, relative deprivation, self-efficacy, self-control and psychological well-being.

The socio-demographic questionnaire includes sex, age, homeplace, grade, profession and types of university.

The ERDS is a two-item scale. Each item is scored on a seven-point Likert scale, with 1 representing very bad and 7 representing very good. A high score indicates a high level of relative deprivation experienced by students. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the ERDS was 0.712.

The GSES includes 10 items, and each item is rated from 1 (not correct) to 4 (correct). Average scores on the GSES ranged from 1 to 4. The higher the score, the better the self-efficacy. The GSES showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.904.

The SCS is a 19-item scale and includes five dimensions: impulse control ( six items), healthy habits (three items), resisting temptation (four items), application to the work (three items) and abstaining from entertainment (three items). A five-point Likert scale is used to score items (1 = completely out of line, 5 = fully compliant). Scores ranges from 19 to 95, and higher scores indicate higher self-control ability. In the study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the SCS was 0.870.

The psychological well-being subscale of MHC-SF includes six items and scores using a five-point Likert scale (0 = never, 5 = everyday). The total scores for the psychological well-being subscale are calculated by averaging the scores for the included items. High scores represent high levels of psychological well-being. In the study, the psychological well-being subscale of the MHC-SF had good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.922.

Ethical considerations

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University (NO. 2021-R-043). All students were informed of the objectives, process, benefits and risks of the study before completing the online questionnaire. The informed consent was obtained from all of the student participants. This was an anonymous survey, and the data were only used for research.

Statistical analysis

Skewness, kurtosis and Q-Q plot were used to test the distribution of the measured variables (relative deprivation, self-efficacy, self-control and psychological well-being). In this study, the scores for skewness of the variables were from − 0.0.425 to 0.058, the scores for kurtosis of the variables were between − 0.277 and 0.883. Furthermore, the four Q-Q plots showed that all scatters were closely distributed to a straight line. There results demonstrated that the measured variables were normal distribution. Mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency and percentage were used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics, relative deprivation, self-efficacy, self-control and psychological capital. Bivariate analysis was used to compare the differences in psychological capital by socio-demographic characteristics. Pearson correlation analysis was used to test the relationships among the measured variables. Model four of PROCESS was conducted to explore the parallel mediations of self-efficacy and self-control in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. The number of bootstrap samples was set as 5000, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was employed for mediation analysis. The structural equation model was used for the robust test. χ2/df, rootmean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) were reported to exam the goodness of fit of the path analysis model for psychological well-being of students. Harman’s single-factor analysis was conducted to examine the common method variance. In the study, a two-sided alpha of 0.05 was used.

Results

Common method variance analysis

Several methods (e.g., anonymity, investigation at different times) were employed to control common method biases that may arise from self-report data collection. Moreover, Harman’s single-factor analysis was used to test the common method biases in the study. The results showed that the characteristic root for seven factors was greater than 1, and 25.20% of the variance could be explained by the first factor, which was less than 40%. Therefore, no significant common method variance was found in the data.

Socio-demographic characteristics of students

A total of 426 undergraduate students completed the online survey. The majority of students were female (73.2%). The mean age of the students was 19.53 (SD 1.38) years old. Over half of the students were freshman (55.4%) and lived in cities (52.6%). Over 40.0% of students studied medicine. Most of the students (91.8%) were from “double tops” and normal universities in Mainland China. Tables 1 and 2 present the socio-demographic characteristics of the student participants.

Bivariate analysis showed that there were no significant differences in psychological well-being related to sex, homeplace, only child status, grade, profession and types of university in the study (each p > 0.05).

Description of measured variables and the correlation analysis

As shown in Table 2, the total score for relative deprivation was 9.06 (SD 1.87), which indicated that students experienced moderate to high levels of relative deprivation. The mean score for psychological well-being was 4.39 (SD 1.09), which indicated that students had high levels of psychological well-being. The mean scores for self-efficacy and self-control were 2.53 (SD 0.57) and 57.14 (SD 8.46), respectively, which indicated that students had moderate levels of self-efficacy and self-control.

Table 2 also presents the correlation results of the measured variables. Psychological well-being was negatively correlated with relative deprivation (r = − 0.264, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with self-efficacy (r = 0.443, p < 0.01) and self-control (r = 0.237, p < 0.01). Relative deprivation had negative correlations with self-efficacy (r = − 0.298, p < 0.01) and self-control (r = − 0.129, p < 0.01). Self-efficacy had a positive correlation with self-control (r = 0.114, p < 0.05). Effect sizes indicated that there were low correlations between the measured variables.

Mediation analysis

The bootstrap method was used to analyze the parallel mediators of self-efficacy and self-control in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. Several covariates (e.g., age, gender, grade and profession) were included to adjust possible confounding. Unstandardized path coefficients were presented to reduce type I errors.

The total effect of relative deprivation on psychological well-being was significant (c = 0.153, SE = 0.027, t = 5.608, p < 0.001). Relative deprivation had a negative direct effect on psychological well-being (B = − 0.071, t = − 2.736, p < 0.01), self-efficacy (B = − 0.094, t = − 6.606, p < 0.001) and self-control (B = − 0.579, t = − 2.644, p < 0.01). The positive direct effects of self-efficacy (B = 0.738, t = 8.691, p < 0.001) and self-control (B = 0.023, t = 4.106, p < 0.001) on psychological well-being were also significant. Moreover, when relative deprivation, self-efficacy and self-control were included in the model, the direct effect of relative deprivation on psychological well-being was significant (c’ = 0.071, SE = 0.026, t = − 2.736, p < 0.01). The results indicated that self-efficacy and self-control acted as parallel mediating variables in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. Table 3 shows the results of the parallel mediation analysis.

Table 4 presents the parallel mediating effects of self-efficacy and self-control. The results showed that the path through self-efficacy had stronger mediating power than self-control, with effect-total indirect effect ratios of 84.15% and 15.85%, respectively.

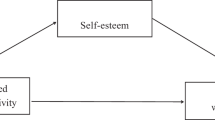

Robust test

According to the psychological stress system theory, the literature and the results above, an initial structural equation model of relative deprivation, self-efficacy, self-control and psychological well-being for Chinese undergraduate students were constructed. The maximum likelihood method was employed for parameter estimation. The model had a good fitting index, χ2/df = 3.239, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.068, GFI = 0.874, IFI = 0.908 and CFI = 0.908. Figure 1 shows the model, which include 4 models and 9 dimensions.

Structural equation model of psychological well-being among Chinese undergraduate students. Note: RD: relative deprivation, SE: self-efficacy, PW: psychological well-being, IC: impulse control, HH: healthy habits, RT: resisting temptation, ATW: application to the work, AFE: abstaining from entertainment.

Table 5 shows that all the paths for the model were significant (p < 0.05). Within, the most effective direct factor for psychological well-being were self-efficacy (1.168), followed by relative deprivation (− 0.152), and self-control ( 0.117). Moreover, the model shows that relative deprivation can affect psychological well-being either through self-efficacy or self-control.

Discussion

Given the worldwide spread of COVID-19, undergraduate students are one of the significantly influenced groups experiencing mental and physical health issues. The findings from this study provide evidence by clarifying the negative association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being and identifying self-efficacy and self-control as protective parallel mediators of the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. This study enriches the knowledge about the underlying mechanism of this association and deepens the understanding of the impacts of self-efficacy and self-control on psychological well-being.

In this study, the first hypothesis assumed students had low levels of psychological well-being, self-efficacy and self-control. However, Our results did not support this assumption. We found that undergraduate students experienced high levels of psychological well-being, which was also inconsistent with the findings of studies from Bangladesh, Canada and the United States of America35,36,37. Studies conducted in other countries showed that undergraduate students experienced stress, anxiety, depression, sleep disorders and low levels of psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic37,38. This difference may be due to the COVID-19 response implemented by universities. Chinese universities developed several crisis responses during the first waves of the COVID-19. Free online psychological counseling, one-for-one psychological assistance and strategies for overcoming stress and frustration were the typical approaches that widely used by universities39. These sophisticated methods help students successfully defend against the negative impacts of the COVID-19, which include infection, social isolation, psychological stress and remote learning, and experience high psychological well-being.

The findings from this study showed that undergraduate students experienced moderate levels of self-efficacy and self-control, with mean scores of 2.53 (SD 0.57) and 57.14 (SD 8.46), respectively. Wester et al.40 investigated 73 undergraduate students pre- and post- COVID-19 transition and found that they had moderate levels of self-efficacy during the COVID-19 transition. Zhou et al.41 surveyed 526 college students during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that students had moderate levels of self-control and low levels of psychological distress. Despite the threat of COVID-19 infection, social isolation and various changes in learning approaches, undergraduate students positively figure out ways to increase their belonging and engagement in life and create opportunities to master professional knowledge and skills for future employment; therefore, they exhibit moderate self-efficacy and self-control. Studies indicate that COVID-19-related stress is a threat or challenge for students’ psychological health, academic achievements and social interactions, while students have the ability to utilize their personal strengths and environment resources to deal with stressful situations that benefit for their self-confidence and self-control38.

In the first hypothesis, we assumed students had high level of relative deprivation. The result of the study confirmed this assumption. The score for relative deprivation in this study was over 50% of the total score, indicating moderate to high relative deprivation perceived by undergraduate students. This result was in line with findings reported by Yoo et al.42. Undergraduate students from different regions of the country usually have diverse social cognitions, lifestyles, and economic conditions that may affect their perceptions and increase their interest in comparing themselves with others43. Moreover, undergraduate students are in a key period of psychological and sociological development, and their immature cognition and changeable mindset may negatively affect their comparison with other colleagues, which may contribute to the severe feelings of relative deprivation44.

Regarding the second hypothesis, we assumed that self-efficacy and self-control can be parallel mediators on the relationship between relative deprivation and psychological well-being, and the results supported the assumptions. In this study, the effects of relative deprivation on psychological well-being among undergraduate students and the underlying mechanisms of self-efficacy and self-control were investigated. The results showed that there was a direct negative effect of relative deprivation on students’ psychological well-being, and relative deprivation could indirectly influence students’ psychological well-being via the intermediary effects of self-efficacy and self-control. Moreover, the mediating effect of self-efficacy was 5 times larger than that of self-control.

In Ohno et al.32, by testing the relationship among social comparison orientation, relative deprivation and subjective well-being, it was found that relative deprivation was negatively correlated with well-being; the higher the level of relative deprivation, the lower the psychological well-being among students. With the experienced emotions of dissatisfaction and frustration, relative deprivation leads to depression and decreases the motivation for achieving goals, which ultimately results in lower psychological well-being45. Some studies show that upward social comparison is an important negative factor for positive well-being and that students who compare themselves with others more frequently have been believed to experience more mental health problems, which may be primarily as a result of relative deprivation46.

In the study, self-efficacy was further verified as a mediating factor between relative deprivation and undergraduate students’ psychological well-being. Upward social comparison orientation often leads students to find their deficiency and disadvantage, such as low education level, household income and social support47. This may influence their confidence to compete with colleagues and pursue profession success, which ultimately results in stunted development of psychological well-being. Suh and Flores found that individuals who fail to overcome relative deprivation experience low self-efficacy and stay passive to gain positive outcomes, including satisfaction, engagement and well-being48. Thus, implementing effective instructional practices to alleviate relative deprivation and improve self-efficacy should be preferentially adopted by educators and psychological counselors during severe pandemics.

Self-control was found to be another important mediator of the impact of relative deprivation on undergraduate students’ psychological well-being. This suggests that self-control plays a parallel mediating role between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. High relative deprivation makes students feel powerless in the face of difficulties49.In the process of upward social comparison, students tend to use negative coping strategies, and their own self-control decreases. When students possess low levels of self-control, it negatively influences their psychological state, and they thereby experience low satisfaction and subjective well-being of the self50. Previous literature shows that, when people have high levels of frustration and disappointment, subjectively, they have negative emotions toward life and lose patience with restraining their desires, which in turn, reducing their psychological well-being51.It is recommended that feasible strategies for promoting students’ self-control should also be applied to enhance their psychological well-being.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered before utilizing the findings of the study. First, a cross-sectional study design was employed, where no prediction can be tested by the study. Second, convenience sampling was used to recruit student participants, which would affect the representation of the study. Third, an online survey was used to collect the data, and it is highly likely that students without network infrastructure were not included. Fourth, only personal-related factors were measured in the study, and other family and university influencing factors were not included in the study. It is suggested that future studies use a longitudinal study design, randomized sampling method, online-offline investigation and family- and university-related measures to investigate undergraduate students’ psychological well-being.

Conclusion

From our investigation of the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being, by considering personal characteristics and in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, some interesting findings emerged. This study verified that relative deprivation negatively correlated with psychological well-being. Furthermore, the findings of the present study showed, for the first time, that self-efficacy and self-control act as parallel mediators in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being. This study clarifies the underlying mechanism of this association, which is useful for developing effective interventions to alleviate students’ relative deprivation and promote self-efficacy and self-control. It is hoped that undergraduate students’ psychological well-being could be improved through these interventions applied by educators and psychological counselors.

Data availability

Data is available from the corresponding author for reasonable requirement.

References

Dong, E., Du, H. & Gardner, L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(5), 533–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30120-1 (2020).

Kochuvilayil, T. et al. COVID-19: knowledge, anxiety, academic concerns and preventative behaviours among Australian and Indian undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Nurs. 30(5–6), 882–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15634 (2021).

Huckins, J. F. et al. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. J. Med. Internet Res. 22(6), e20185. https://doi.org/10.2196/20185 (2020).

Elmer, T., Mepham, K. & Stadtfeld, C. Students under lockdown: comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One. 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337 (2020).

Silva, A. N. D. et al. Demographics, socioeconomic status, social distancing, psychosocial factors and psychological well-being among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18(14), 7215. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147215 (2021).

Liu, X., Ping, S. & Gao, W. Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological well-being as they experience university life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16(16), 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162864 (2019).

Casale, S., Lecchi, S. & Fioravanti, G. The association between psychological well-being and problematic use of internet communicative services among young people. J. Psychol. 149(5), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.905432 (2015).

Power, S. A., Madsen, T. & Morton, T. A. Relative deprivation and revolt: current and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 35, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.010 (2020).

Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I. & Skylark, W. J. Social comparison processes in the experience of personal relative deprivation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 48(9), 519–532 (2018).

Conrad, R. et al. Significance of anger suppression and preoccupied attachment in social anxiety disorder: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychia. 21(1), 116 (2021).

Xia, Y. & Ma, Z. Relative deprivation, social exclusion, and quality of life among Chinese internal migrants. Public. Health. 186, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.038 (2020).

Zhao, H. & Zhang, H. How personal relative deprivation influences moral disengagement: the role of malicious envy and honesty-humility. Scand. J. Psychol. 63(3), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12791 (2022).

Yang, X. Y., Hu, A. & Schieman, S. Relative deprivation in context: how contextual status homogeneity shapes the relationship between disadvantaged social status and health. Soc. Sci. Res. 81, 157–169 (2019).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 (1977).

Berens, E. M., Pelikan, J. M. & Schaeffer, D. The effect of self-efficacy on health literacy in the German population. Health Promot Int. 37(1), daab085 (2022).

Puente-Diaz, R. Creative self-efficacy: an exploration of its antecedents, consequences, and applied implications. J. Psychol. 150(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2015.1051498 (2016).

Klassen, R. M. & Klassen, J. R. L. Self-efficacy beliefs of medical students: a critical review. Perspect. Med. Educ. 7(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0411-3 (2018).

Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M. & Galand, B. Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: comparing three theoretical frameworks. J. Youth Adolesc. 48(2), 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0952-0 (2019).

Grotan, K., Sund, E. R. & Bjerkeset, O. Mental health, academic self-efficacy and study progress among college students-the SHoT study, Norway. Front. Psychol. 10, 45. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00045 (2019).

Schmidt-Barad, T. & Uziel, L. When (state and trait) powers collide: effects of power-incongruence and self-control on prosocial behavior. Personal Individ Differ. 162, 110009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110009 (2020).

Moilanen, K. L., Shaw, D. S. & Fitzpatrick, A. Self-regulation in early adolescence: relations with mother-son relationship quality and maternal regulatory support and antagonism. J. Youth Adol. 39(11), 1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9485-x (2010).

Bridgett, D. J., Burt, N. M., Edwards, E. S. & Deater-Deckard, K. Intergenerational transmission of self-regulation: a multidisciplinary review and integrative conceptual framework. Psychol. Bull. 141(3), 602–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038662 (2015).

Finley, A. J. & Schmeichel, B. J. Aftereffects of self-control on positive emotional reactivity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45(7), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218802836 (2019).

Li, J. et al. Does self-control promote prosocial behavior? Evidence from a longitudinal tracking study. Child. (Basel). 9(6), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060854 (2022).

Vazsonyi, A. T., Mikuska, J. & Kelley, E. L. It’s time: a meta-analysis on the self-control-deviance link. J. Crim Justice. 48, 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.10.001 (2017).

Fan, W., Ren, M., Zhang, W., Xiao, P. & Zhong, Y. Higher self-control, less deception: the effect of self-control on deception behaviors. Adv. Cogn. Psychol. 16(3), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.5709/acp-0299-3 (2020).

Siddiqui, A. et al. Correlation of job stress and self-control through various dimensions in Beijing hospital staff. J. Affect. Disord. 294, 916–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.07.094 (2021).

Simons, R. M., Walters, K. J., Keith, J. A. & Simons, J. S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and conduct problems: the role of self-control demands. J. Trauma. Stress. 34(2), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22601 (2021).

Jiang, Q. J. Medical Psychology (China Science Publishing & Media Letd, 1993).

Gero, K., Miyawaki, A. & Kawachi, I. Relative income deprivation and all-cause mortality in Japan: do life priorities matters? Ann. Behav. Med. 54(9), 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaaa010 (2020).

Barbayannis, G. et al. Academic stress and mental well-being in college students: correlations, affected groups. An COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 13, 886344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.886344 (2022).

Ohno, H., Lee, K. T. & Maeno, T. Feelings of personal relative deprivation and subjective well-being in Japan. Behav. Sci. (Basel). 13(2), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020158 (2023).

Lilly, K. J., Sibley, C. G. & Osborne, D. Examining the indirect effect of income on well-being via individual-based relative deprovation: longitudinal mediation with a random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Int. J. Psychol. 59(3), 368–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.13097 (2024).

Farley, H. Promoting self-efficacy in patients with chronic disease beyond traditional education: a literature review. Nurs. Open. 7(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.382 (2019).

Ali, M., Uddin, Z., Hossain, K. M. A. & Uddin, T. R. Depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal behavior among Bangladeshi undergraduate rehabilitation students: an observational study amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Sci. Rep. 5(2), e549. https://doi.org/10.1001/hsr2.549 (2022).

King, N. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of first-year undergraduate students studying at a major Canadian university: a successive cohort study. Can. J. Psychia. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437221094549 (2022).

Lukowski, A. F., Karayianis, K. A., Kamliot, D. Z. & Tsukerman, D. Undergraduate student stress, sleep, and health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav. Med. 28, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/089642289.2022.2085651 (2022).

Ikbar, R. R., Amit, N., Subramaniam, P. & Ibrahim, N. Relationship between self-efficacy, adversity quotient, COVID-19-related stress and academic performance among the undergraduate students: a protocol for a systematic review. PLoS One. 17(12), e0278635. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278635 (2022).

Kim, H. R. & Kim, E. J. Factors associated with mental health among international students during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18(21), 11381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111381 (2021).

Wester, E. R., Walsh, L. L., Arango-Caro, S. & Callis-Duehl, K. L. Student engagement declines in STEM undergraduates during COVID-19-driven remote learning. J. Microbiol Biol. Educ. 22(1), 22.1.50. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22ia.2385 (2021).

Zhou, G. Y., Yang, B., Li, H., Feng, Q. S. & Chen, W. Y. The influence of physical exercise on college students’ life satisfaction: the chain mediating role of self-control and psychological distress. Front. Psychol. 14, 1071615. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1071615 (2023).

Yoo, G., Yeon, Y. D. & Baek, J. Effects of subjective socioeconomic status on relative deprivation and subjective well-being among college students: testing the silver-spoon-discourse based belongingness in Korean society. Fam Envir Res. 57(3), 329–340 (2019).

Ding, Q., Liang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Huang, F. The impact of attribution for the rich-poor gap on psychological entitlement among low social class college students: the mediating effect of relative deprivation. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 27(5), 1041–1044. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2019.05.038 (2019).

Guo, Y. & Xia, L. Relational model of relative deprivation, revenge, and cyberbullying: a three-tine longitudinal study. Aggressive Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.22079 (2023).

Bjarehed, J., Sarkohi, A. & Andersson, G. Less positive or more negative? Future-directed thinking in mild to moderate depression. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 39, 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070902966926 (2010).

Buunk, A. P. & Gibbons, F. X. Social comparison: the end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 102, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007 (2007).

Elgar, F. J. et al. Absolute and relative family affluence and psychosomatic symptoms in adolescents. Social Sci. Med. 91, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.030 (2013).

Suh, H. N. & Flores, L. Y. Relative deprivation and career decision self-efficacy: influences of self-regulation and parental educational attainment. Career Develop Quart. 65(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12088 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Wu, Y. & Xiong, M. Fatherinvolvement and school adjustment of rural boarding junior high school students: the mediate effect of self-control and the moderate effect of relative deprivation. J. Psychol. Sci. 44(6), 1354–1360 (2021).

Yeung, C. T. Y. & Chui, R. C. F. A study on the impact of involvement in violent online game and self-control on Hong Kong young adults’ psychological well-being. Edu Communic Technol. Yearbook. 2018, 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8896-4_14 (2018).

Yu, G. L. A new interpretation of mental health: the well-being perspective. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. 1, 72–81 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the students who submitted the online questionnaires.

Funding

This study was funded by The Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University (2020GN096).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YFG designed the study, collected and analysed data, wrote-reviewed & edited the manuscript. FYY designed the study, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; XYL, FYY designed the study, wrote and revised the manuscript. FYSgave suggestions in designing the study, collected data, revised and edited the manuscript; XLH gave suggestions in designing the study, collected and analysed data and revised the manuscript; ANW gave suggestions in designing the study, collected data, and revised the manuscript; YNJ gave suggestions in designing the study, collected data, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, one University (NO. 2021-R-043). All student participants were required to review the explaining statement (including objectives, procedure, benefits and risks of the study) before filling the questionnaire. The study was conducted strictly adhering to the Helsinki Declaration.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, YF., Yue, FY., Lu, XY. et al. Roles of self-efficacy and self-control in the association between relative deprivation and psychological well-being among undergraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 14, 24361 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75769-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75769-4