Abstract

Recent advancements in next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have created new opportunities for comprehensive screening of multiple parasite species. In this study, we cloned the 18 S rDNA V9 region of 11 species of intestinal parasites into plasmids. Equal amounts and concentrations of these 11 plasmids were pooled, and amplicon NGS targeting the 18 S rDNA V9 region was performed using the Illumina iSeq 100 platform. A total of 434,849 reads were identified, and all 11 parasite species were detected, although the number of output reads for each parasite varied. The read count ratio, in descending order, was as follows: Clonorchis sinensis, 17.2%; Entamoeba histolytica, 16.7%; Dibothriocephalus latus, 14.4%; Trichuris trichiura, 10.8%; Fasciola hepatica, 8.7%; Necator americanus, 8.5%; Paragonimus westermani, 8.5%; Taenia saginata, 7.1%; Giardia intestinalis, 5.0%; Ascaris lumbricoides, 1.7%; and Enterobius vermicularis, 0.9%. We found that the DNA secondary structures showed a negative association with the number of output reads. Additionally, variations in the amplicon PCR annealing temperature affected the relative abundance of output reads for each parasite. These findings can be applied to improve parasite detection methodologies and ultimately enhance efforts to control and prevent intestinal parasitic infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intestinal parasite infections, which represent a significant global public health concern, disproportionately affect marginalized communities with limited access to clean water and sanitation facilities1,2,3,4. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 3.5 billion people are at risk of intestinal parasite infection, and of this number, approximately 1.5 billion people currently suffer from some form of intestinal parasitic infection5.

Intestinal parasites constitute a diverse group of organisms, including helminths such as nematodes (roundworms), trematodes (flatworms), and cestodes (tapeworms)6, as well as protozoa such as Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica7. These insidious pathogens represent a major threat to public health and often lead to severe morbidity, malnutrition, and even mortality6,8. It has also been reported that understanding disease-related pathogens and accurately diagnosing infectious illnesses are paramount for the development of effective control and prevention strategies9. This need has spurred decades of research and innovation in the field of parasitology.

Conventional methods for parasite detection, including microscopic examination10,11, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)12,13,14,15,16, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, still play a crucial role in the diagnosis and monitoring of intestinal parasite infections. However, they do have some limitations.

The accuracy of microscopy with respect to the identification of intestinal parasites depends on the skill level of the operating technician, and microscopic examinations may not lead to the detection of infections when the number of parasites present is low. It can also be time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring trained personnel and specialized equipment25,26,27,28. Further, serological assays, such as ELISA, show promise for diagnosing parasitic infections, but when used in isolation, they are prone to showing higher rates of false results, especially in cases where there is cross-reactivity among antigens from different parasite species29. Furthermore, one of the drawbacks of PCR is its requirement for meticulously designed primers tailored to specific target parasites30, and designing these primers demands an in-depth understanding of the parasite’s genetic makeup. Thus, the process is often time-consuming and expensive.

Therefore, new strategies are needed for screening multiple samples for various pathogens, and the advancement of molecular diagnostics requires rigorous validation of lab-developed assays for accurate infectious disease diagnosis31. Recent advances in molecular biology and next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have opened new avenues for the rapid and accurate screening of multiple parasite species. Specifically, metabarcoding, a methodology that enables the simultaneous screening of multiple parasite species within a single sample, has shown great promise in the field of parasitology32,33,34,35,36.

In this study, 11 intestinal parasite species were screened using 18 S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene amplicon-based NGS. The purpose of this study was to simultaneously detect these 11 intestinal parasites using metabarcoding and investigate the optimization of library preparation protocols for NGS so as to shed light on factors affecting NGS results in relation to parasitic infections. The results obtained may be useful for improving diagnostic accuracy and may ultimately aid public health efforts to control and prevent intestinal parasitic infections.

Methods

DNA extraction

Helminth samples (Ascaris lumbricoides, Clonorchis sinensis, Dibothriocephalus latus, Enterobius vermicularis, Fasciola hepatica, Necator americanus, Paragonimus westermani, Taenia saginata, Trichuris trichiura) preserved in ethanol as specimens and protozoa samples (Giardia intestinalis, Entamoeba histolytica) cultured in the laboratory of the Department of Tropical Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, were used in this study37,38. The DNA of the parasites was extracted using the Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA samples were stored at -80 °C until needed.

Thymine-adenine (TA) clone targeting of the 18 S rRNA gene V9 region

PCR was performed to amplify the V9 region of the 18 S rRNA gene of the parasites using the individual DNA samples. The primers used were 1391 F (5’- GTACACACCGCCCGTC-3’) and EukBR (5’-TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3’). The cloning of the amplicons of the 18 S V9 regions of the 11 intestinal parasites under study was performed using the TOPcloner TA Kit (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The recombinant colonies obtained were then stored at -80 °C until use. In brief, the cloned plasmids were extracted using the Exprep Plasmid SV Mini Kit (GeneAll, Seoul, Korea) after culturing overnight in Luria–Bertani broth containing ampicillin. Finally, the concentrations of the extracted plasmids were measured using a Quantus™ fluorometer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The flow chart shows the outline of sample preparation and amplicon sequencing for this study (Fig. 1).

Restriction enzyme for plasmid linearization

To minimize the steric hindrance of the circular plasmids and primers, the plasmids were linearized using a restriction enzyme, NcoI (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) at a concentration of 10 U/µL, which has one restriction site in all 11 types of plasmids. Three groups of samples were prepared for the amplicon NGS analysis: The first group comprised 11 samples that were not treated with the restriction enzyme. The second group comprised 11 samples that were first pooled and then simultaneously treated with the restriction enzyme. The third group comprised 11 samples that were treated individually with the restriction enzyme and thereafter pooled. There were two plasmid concentrations: 20 ng/µL and 2 ng/µL.

Illumina sequencing for eukaryotic metabarcoding

The plasmids of the 11 parasite species were amplified using primers targeting the 18 S rRNA V9 region, with adaptors for NGS attached to the primers: 1391 F (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG GTACACACCGCCCGTC-3′) and EukBR (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAG TGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′)33. We chose to amplify the V9 region of the 18 S rDNA due to its potential to efficiently capture a broader range of eukaryotes on the Illumina sequencing platform39,40. The master mix, KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche Sequencing Solutions, Pleasanton, CA, USA), contained the primers and 3 µl of pooled total DNA, derived by diluting each of the 11 plasmid DNAs to equal concentrations based on the lowest measured plasmid concentration of 20 ng/µl. PCR amplification was then performed using an Applied Biosystems Veriti 96-Well Fast Thermal Cycler (Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA, USA) as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 98 °C for 30 s; 55 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. A limited-cycle (8-cycle) amplification step was also performed to add multiplexing indices and Illumina sequencing adapters. Thereafter, mixed amplicons were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina iSeq 100 sequencing system using the Illumina iSeq™ 100 i1 Reagent v2 kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In addition, to evaluate the effect of annealing temperature on the NGS output during the amplicon PCR process, various annealing conditions ranging from 40 to 70 °C, in 3 °C increments, were tested for library preparation.

Bioinformatic procedures

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology v2 (QIIME 2™) (2023.2) was used to analyze the iSeq 100 data41. Low-quality sequence reads were demultiplexed and trimmed using Cutadapt (v4.5)42. Thereafter, the trimmed reads were denoised and dereplicated. Chimera reads were filtered out using the DADA2 (v1.26)43, a widely used noise reduction algorithm in 18 S rDNA metabarcoding44,45,46,47. To obtain a table for the taxonomic assignation of amplicon sequence variant sequences, we utilized the complete set of sequences available in the NCBI nucleotide database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/) as it encompasses a broader range of parasite sequences compared to curated databases. We conducted an advanced search for gene names, specifically “18S rRNA”48. Thereafter, we extracted sequences from the NCBI database to construct a database for vertebrates and parasites. Subsequently, clustered sequences with 100% identity were compared against the 18 S rRNA sequences in the database to generate the classification table. The taxonomical classification of the representative sequences was performed using a feature classifier based on the consensus search method49. Unassigned reads (0.07% of the total reads) were removed from subsequent analyses.

Prediction of 18 S rDNA V9 secondary structure

The DNA secondary structure of the 18 S rDNA V9 region of each parasite was predicted, and the number of intra-GC pairs was counted using Vector Builder software (https://www.vectorbuilder.kr/tool/dna-secondary-structure.html) and Geneious Prime (version 2023.2.1, https://www.geneious.com).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.3.2; R Core Team, 2023). Data visualizations were created with the ggplot2 package (v3.5.1; Wickham, 2016). To investigate the relationship between the number of intra-GC base pairs in the hairpin structure (independent variable) and the relative abundance value (dependent variable) expressed as a percentage for each target species at 55°C as the annealing temperature for amplicon PCR, we conducted a simple linear regression analysis using the ‘lm’ function in R. P-value and regression coefficient reported here are derived from the regression model. A significance level of 0.05 was set for p-values.

Results

Metabarcoding of the 18 S V9 region of the 11 parasites under study

After cloning the 18 S rDNA V9 region (18 S V9) of human parasites detectable in human stool, 11 plasmids were extracted and pooled in equal amounts to prepare libraries for parasite metabarcoding. The NGS output showed a total of 434,849 reads, and all 11 parasite species were detected, suggesting that parasite metabarcoding is an effective method for detecting intestinal parasites. Interestingly, the sequenced read count ratio was different for each parasite despite the use of the same input amount (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). Further, the read count ratio decreased as follows: C. sinensis, 74,893 reads (17.21%); E. histolytica, 73,045 reads (16.79%); D. latus, 62,728 reads (14.41%); T. trichiura, 47,320 reads (10.87%); F. hepatica, 37,994 reads (8.73%); N. americanus, 37,101 reads (8.53%); P. westermani, 37,017 reads (8.51%); T. saginata, 31,184 reads (7.17%); G. intestinalis, 21,895 reads (5.03%); A. lumbricoides, 7,529 reads (1.73%); and E. vermicularis, 4,143 reads (1.73%).

Relative abundances of the sequence reads in 11 intestinal parasite species: Ascaris lumbricoides, Clonorchis sinensis, Dibothriocephalus latus, Entamoeba histolytica, Enterobius vermicularis, Fasciola hepatica, Giardia intestinalis, Necator americanus, Paragonimus westermani, Taenia saginata, and Trichuris trichiura.

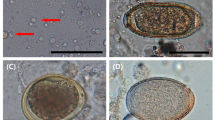

The DNA sequence of the 18 S V9 region formed a specific DNA secondary structure (a hairpin structure). Thus, we hypothesized that the GC base pairs in the hairpin structure are associated with the different sequenced ratios. The hairpin structures were computationally constructed, and the number of intra-GC pairs therein was counted (Fig. 3; Table 1). Next, linear regression analysis was performed between the NGS output ratio (a dependent variable) and the number of GC pairs in the hairpin (an independent variable). Thus, we observed that the greater the number of GC pairs in the hairpin of the 18 S V9 region, the lower the NGS output ratio, and this relationship was statistically significant (regression coefficient = − 1.0473, p = 0.00485; intercept = 28.6097, p = 0.00048 in Vector Builder). We repeated the test using the number of intra-GC pairs from a different program (Geneious Prime) and it also produced almost the same result as the previous one (regression coefficient = − 1.0133, p = 0.0179; intercept = 27.5076, p = 0.0022).

Secondary structure of the 18 S rDNA V9 region and GC pair numbers. (a) Trichuris trichiura, (b) Fasciola hepatica, (c) Clonorchis sinensis, (d) Dibothriocephalus latus, (e) Enterobius vermicularis, (f) Necator americanus, (g) Giardia intestinalis, (h) Entamoeba histolytica, (i) Paragonimus westermani, (j) Ascaris lumbricoides, (k) Taenia saginata.

Effect of plasmid linearization on NGS output

We used the restriction enzyme to linearize the plasmid and prepared three sample groups for amplicon NGS analysis: untreated samples, samples pooled before enzyme treatment, and samples treated individually with the enzyme before pooling (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 2). Amplicon NGS performed on these groups revealed no differences in relative abundance between the enzyme-treated and non-treated samples. This result was consistent even in the 10-fold diluted samples (Fig. 4b).

Bar plot showing the relative abundances of the plasmids of 11 species. Plasmid concentration at (a) 20 ng/µl and (b) 2 ng/µl. Bottom, no restriction enzyme treatment was performed; middle, the 11 plasmids were pooled first and then treated with the restriction enzyme, Nco1; top, each plasmid was first treated with the restriction enzyme (Nco1) and then pooled.

Metabarcoding at different annealing temperatures

We evaluated the effect of annealing temperature on the amplicon PCR process. In the first experiment (Figs. 2 and 3), the annealing temperature for the amplicon PCR process targeting the 18 S V9 region was 55 °C. Given that PCR efficiency may vary depending on the annealing temperature, we set various annealing conditions ranging from 40 to 70 °C with 3 °C increments for library preparation. As the temperature increased, an interesting NGS output pattern emerged; the number of reads for the different parasites became more similar (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 3). Specifically, parasites that were initially detected in lower numbers, such as A. lumbricoides, E. vermicularis, and T. saginata, showed an increasing number of reads as the temperature increased.

Only F. hepatica reads showed a different pattern as the annealing temperature increased; its read number rather decreased with increasing temperature. Its relative abundance was only 0.2% at 70 °C. To confirm the decrease in the number of F. hepatica reads with increasing annealing temperature, PCR was performed, and for each individual plasmid containing the 18 S V9 region, the concentration of each amplicon was measured at 5 °C increments in annealing temperature. Thus, we observed that the F. hepatica amplicon concentration was notably lower than that of the other parasites at higher temperatures (65 and 70 °C) (Table 2).

Discussion

Metabarcoding, which employs high-throughput sequencing of 18 S rRNA gene amplicons, plays a crucial role in the assessment of the diversity of eukaryotes in various ecosystems39. In this study, we used metabarcoding to screen various human intestinal parasites simultaneously. Studies in this regard are limited, and specifically, there are no reports on the identification of efficient methods for such analyses.

Via metabarcoding, we detected all 11 intestinal parasite species. DNA metabarcoding involves the utilization of NGS technology as an extension of barcoding. The advent of readily available NGS technologies has transformed the fields of clinical and public health microbiology50,51,52. Apart from expedited and precise pathogen identification, the amalgamation of high-throughput methodologies and bioinformatics offers novel understanding regarding disease transmission, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance.

Several studies have documented the use of NGS in detecting a wide range of parasites in humans. Targeted amplicon NGS identified 16 species of blood-borne helminths and protozoa, including Plasmodium falciparum, Leishmania infantum, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Brugia malayi53. Intestinal eukaryotic protists were detected in stool samples from healthy Tunisian individuals, including Dientamoeba fragilis, Giardia intestinalis, Cryptosporidium spp., Blastocystis sp., and Entamoeba sp36. Furthermore, long-read nanopore sequencing technology has proven effective in accurately detecting and characterizing a diverse range of filarial worms54. NGS has also been employed to identify Pneumocystis jirovecii and other pathogens in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with lung diseases55,56.

We investigated the effects of GC bonds, annealing temperature, and linearization of the plasmid DNA on the sequencing results of pooled libraries containing 11 species of intestinal parasites. Thus, we observed that the 11 intestinal parasite species all had different relative abundances. This could be attributed to the correlation between the GC pairs of the DNA secondary structure. Additionally, GC-rich regions, owing to the formation of stable and complex secondary structures within a DNA template, can block DNA polymerase during PCR and lead to ineffective amplification57. These regions in templates also often form intricate secondary structures that can resist denaturation during the PCR annealing phase. Moreover, the primers utilized for amplifying these GC-rich regions have a propensity to self-anneal and cross-anneal, creating stem-loop structures that may hinder the progression of DNA polymerase along the template58. Hydrogen bonding plays a crucial role in the interactions within a DNA base pair. The hydrogen bond energy between nucleobases that form a base pair has been calculated in numerous theoretical studies59. Thus, it has been reported that the G-C base pair is stronger than the A-T base pair owing to the greater number of hydrogen bonds formed between them. Specifically, the G-C base pair forms three hydrogen bonds, while the A-T base pair forms two hydrogen bonds60. Additionally, other factors, such as length, may also have an effect61.

Increasing the annealing temperature during PCR enhances the amplification of a specific DNA sequence57. This is due to improved specificity, reduced primer-dimer formation, increased stability of primer-template interaction, and optimal Tm (melting temperature) matching, all facilitated by the principles of thermodynamics and DNA base pairing. Specifically, an escalation in temperature increases the kinetic energy of DNA strands, diminishing the possibility of nonspecific interactions and fostering the creation of robust, targeted primer-template pairings. Further, at high temperatures, non-specific DNA regions are less likely to form stable interactions with the primers due to weak binding affinity. This minimizes the potential for non-specific amplification.

The effect of Tm on GC content does not necessarily disappear at high temperatures; it remains a factor that influences primer-template interactions. High annealing temperatures can compensate to some extent for differences in GC content between primers and templates, but it is still important to consider GC content when designing primers, regardless of the annealing temperature employed.

In summary, higher annealing temperatures ensure that primers bind specifically to the target DNA region, minimizing non-specific amplification and promoting efficient and accurate DNA amplification. In this study, we observed that when the temperature was raised, A. lumbriocoides, E. vermicularis, G. intestinalis, and T. saginata were well detected. Therefore, if metabarcoding is performed to detect these species, then it is recommended to set a relatively high annealing temperature. For F. hepatica, the read number was strangely reduced when the temperature was high. Therefore, in this case, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact that detection may become challenging at high annealing temperatures.

The results obtained notwithstanding, this study had some limitations. Similar amplification was achieved at elevated temperatures for all samples except F. hepatica. Although this species was characterized, the results obtained from its sequencing at high temperatures were limited; thus, we decided that an annealing temperature of 55 °C was the most appropriate for amplicon sequencing.

One limitation of our study is the use of universal eukaryotic primers. While this approach offers broader taxonomic coverage, it can also amplify DNA from hosts and other food materials present in faecal samples. This can lead to a masking effect, where parasite DNA is obscured by the more abundant host or non-target DNA, potentially underestimating parasite burden or missing low-abundance parasites32,33,62. To address this limitation in future studies, several strategies can be considered. Firstly, methods to decrease host DNA abundance, such as enzymatic removal or alternative depletion techniques based on previous studies53,63, can be employed. Additionally, using other target regions, such as the ITS2 region for nemabiome analysis and mitochondrial rRNA genes for helminth metabarcoding, as complementary methods to 18 S rDNA amplicon sequencing64,65,66,67,68,69,70, can provide highly accurate identification of nematode and helminth parasites, although this may reduce broader parasite detection coverage, particularly for protozoa. Another limitation of our study is the lack of validation with real-world samples, such as faeces. Despite our efforts, finding suitable faecal samples with multiple parasite infections was not possible. Nevertheless, our study provides valuable insights into factors influencing read counts and NGS library preparation optimization. This paves the way for future research using more specific methods for parasite detection in real-world samples.

Conclusions

Our findings provide insights into the factors that influence NGS read count and the optimization of library preparation protocols for parasite metabarcoding. The number of GC bonds in the secondary hairpin structure of amplicon DNA was found to be a significant determinant of amplification efficiency. Optimizing the annealing temperature for specific library preparation protocols can be proposed as a potential approach to improve the detection rate of specific parasites. Advancements in NGS technology, leading to greater accuracy and reduced costs, make the routine use of metabarcoding for helminth detection more feasible. These advancements hold promise for enhancing efforts to control and prevent intestinal parasitic infections, ultimately contributing to better public health outcomes.

Data availability

Raw sequence data are available in NCBI GenBank under BioProject PRJNA1026347.

Abbreviations

- GC:

-

Guanine–cytosine

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

References

Njambi, E., Magu, D., Masaku, J., Okoyo, C. & Njenga, S. M. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections and Associated Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Risk factors among School Children in Mwea Irrigation Scheme, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. J. Trop. Med. 3974156 (2020).

Aguirre, A. A. et al. The one health approach to toxoplasmosis: Epidemiology, Control, and prevention strategies. EcoHealth. 16(2), 378–390 (2019).

Kim, J. Y., Oh, S., Yoon, M. & Yong, T. S. Importance of balanced attention toward Coronavirus Disease 2019 and neglected Tropical diseases. Yonsei Med. J. 64(6), 351–358 (2023).

Miswan, N., Singham, G. V. & Othman, N. Advantages and Limitations of Microscopy and Molecular detections for diagnosis of soil-transmitted Helminths: an overview. Helminthologia. 59(4), 321–340 (2022).

World Health Organization (WHO). Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections. (2023). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections Accessed 18 January 2023.

Haque, R. Human intestinal parasites. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 25(4), 87–91 (2007).

Aiemjoy, K. et al. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminth and intestinal protozoan infections in preschool-aged children in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96 (4), 866–872 (2017).

Workineh, L., Almaw, A. & Eyayu, T. Trend Analysis of Intestinal parasitic infections at Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia from 2017 to 2021: A five- year retrospective study. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 1009–1018 (2022).

van Seventer, J. M. & Hochberg, N. S. Principles of infectious diseases: transmission, diagnosis, Prevention, and control. Int. Encyclopedia Public. Health 22–39 (2017).

Zhang, W. & McManus, D. P. Recent advances in the immunology and diagnosis of echinococcosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 47(1), 24–41 (2006).

ten Hove, R. J. et al. Molecular diagnostics of intestinal parasites in returning travellers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 28(9), 1045–1053 (2019).

Ramzy, R. M. Field application of PCR-based assays for monitoring Wuchereria bancrofti infection in Africa. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 96(Suppl 2), S55–S59 (2012).

Yamasaki, H. et al. Mitochondrial DNA diagnosis for taeniasis and cysticercosis. Parasitol Int. 55, S81–S85. (2006).

Hong, K. et al. Fatal primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri: The First Imported Case in Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 64(10), 641–645 (2023).

Pontes, L. A., Dias-Neto, E. & Rabello, A. Detection by polymerase chain reaction of Schistosoma mansoni DNA in human serum and feces. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66(2), 157–162 (2002).

Abath, F. G., Gomes, A. L., Melo, F. L., Barbosa, C. S. & Werkhauser, R. P. Molecular approaches for the detection of Schistosoma mansoni: Possible applications in the detection of snail infection, monitoring of transmission sites, and diagnosis of human infection. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 101(Suppl 1), 145–148 (2006).

Pardo, J. et al. Application of an ELISA test using Schistosoma Bovis adult worm antigens in travellers and immigrants from a schistosomiasis endemic area and its correlation with clinical findings. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 39(5), 435–440 (2007).

Melrose, W. D., Durrheim, D. D. & Burgess, G. W. Update on immunological tests for lymphatic filariasis. Trends Parasitol. 20(6), 255–257 (2004).

Hernández, A. et al. Cystic echinococcosis: Analysis of the serological profile related to the risk factors in individuals without ultrasound liver changes living in an endemic area of Tacuarembó. Uruguay Parasitol. 130(4), 455–460 (2005).

Carmena, D., Benito, A. & Eraso, E. The immunodiagnosis of Echinococcus multilocularis infection. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13(5), 460–475 (2007).

Bueno, E. C. et al. Application of synthetic 8-kD and recombinant GP50 antigens in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72(3), 278–283 (2005).

Espinoza, J. R. et al. Evaluation of FAS2-ELISA for the serological detection of Fasciola hepatica infection in humans. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76(5), 977–982 (2007).

Katanik, M. T., Schneider, S. K., Rosenblatt, J. E., Hall, G. S. & Procop, G. W. Evaluation of ColorPAC Giardia/Cryptosporidium rapid assay and ProSpect Giardia/Cryptosporidium microplate assay for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in fecal specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39(12), 4523–4525 (2001).

Weitzel, T., Dittrich, S., Möhl, I., Adusu, E. & Jelinek, T. Evaluation of seven commercial antigen detection tests for Giardia and Cryptosporidium in stool samples. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12(7), 656–659 (2006).

Ricciardi, A. & Ndao, M. Diagnosis of parasitic infections: What’s going on? J. Biomol. Screen. 20(1), 6–21 (2015).

Hooshyar, H., Rostamkhani, P., Arbabi, M. & Delavari, M. Giardia lamblia infection: Review of current diagnostic strategies. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 12(1), 3–12 (2019).

Soares, R. & Tasca, T. Giardiasis: an update review on sensitivity and specificity of methods for laboratorial diagnosis. J. Microbiol. Methods. 129, 98–102 (2016).

Ruenchit, P. State-of-the-art techniques for diagnosis of Medical parasites and arthropods. Diagnostics (Basel). 11(9), 1545 (2021).

Ashraf, M. A. et al. Conventional and Molecular Diagnosis of Parasites. CABI. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1079/9781800621893.0004

Ye, J. et al. Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 13, 134 (2012).

Burd, E. M. Validation of laboratory-developed molecular assays for infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23(3), 550–576 (2010).

Choi, J. H. et al. Metabarcoding of pathogenic parasites based on copro-DNA analysis of wild animals in South Korea. Heliyon 10(9), e30059 (2024).

Kim, S. L. et al. Metabarcoding of bacteria and parasites in the gut of Apodemus agrarius. Parasit. Vectors. 15(1), 486 (2022).

Davey, M. L., Utaaker, K. S. & Fossøy, F. Characterizing parasitic nematode faunas in faeces and soil using DNA metabarcoding. Parasit. Vectors. 14(1), 422 (2021).

Aivelo, T. & Medlar, A. Opportunities and challenges in metabarcoding approaches for helminth community identification in wild mammals. Parasitology. 145(5), 608–621 (2018).

Chihi, A., Andersen, L. O. B., Aoun, K., Bouratbine, A. & Stensvold, C. R. Amplicon-based next-generation sequencing of eukaryotic nuclear ribosomal genes (metabarcoding) for the detection of single-celled parasites in human faecal samples. Parasite Epidemiol. Control. 17, e00242 (2022).

Park, E. A., Kim, J., Shin, M. Y. & Park, S. J. Kinesin-13, a motor protein, is regulated by Polo-like kinase in Giardia lamblia. Korean J. Parasitol. 60(3), 163–172 (2022).

Lee, Y. A. & Shin, M. H. Involvement of NOX2-derived ROS in human hepatoma HepG2 cell death induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Parasites Hosts Dis. 61(4), 388–396 (2023).

Bukin, Y. S. et al. The effect of metabarcoding 18S rRNA region choice on diversity of microeukaryotes including phytoplankton. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39(9), 229 (2023).

Choi, J. & Park, J. S. Comparative analyses of the V4 and V9 regions of 18S rDNA for the extant eukaryotic community using the Illumina platform. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 6519 (2020).

Bokulich, N. A. et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 6(1), 90 (2018).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13(7), 581–583 (2016).

Salmaso, N. et al. Metabarcoding protocol: analysis of protists using the 18S rRNA gene and a DADA2 pipeline (Version 1). (2021). https://zenodo.org/record/5233527

Harbuzov, Z. et al. Amplicon sequence variant-based meiofaunal community composition revealed by DADA2 tool is compatible with species composition. Mar. Genomics. 65, 100980 (2022).

Kenmotsu, H., Uchida, K., Hirose, Y. & Eki, T. Taxonomic profiling of individual nematodes isolated from copse soils using deep amplicon sequencing of four distinct regions of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. PloS One. 15(10), e0240336 (2020).

Tytgat, B. et al. Monitoring of marine nematode communities through 18S rrna metabarcoding as a sensitive alternative to morphology. Ecol. Ind. 107, 105554 (2019).

Arias-Giraldo, L. M. et al. Identification of blood-feeding sources in Panstrongylus, Psammolestes, Rhodnius and Triatoma using amplicon-based next- generation sequencing. Parasit. Vectors. 13(1), 434 (2020).

Sureshan, S. C., Mohideen, H. S. & Nair, T. S. Gut metagenomic profiling of Gossypol Induced Oxycarenus Laetus (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae) reveals Gossypol tolerating bacterial species. Indian J. Microbiol. 62(1), 54–60 (2022).

Gargis, A. S., Kalman, L. & Lubin, I. M. Assuring the quality of Next-Generation Sequencing in Clinical Microbiology and Public Health Laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54(12), 2857–2865 (2016).

Socea, J. N., Stone, V. N., Qian, X., Gibbs, P. L. & Levinson, K. J. Implementing laboratory automation for next-generation sequencing: benefits and challenges for library preparation. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1195581 (2023).

Satam, H. et al. Next-generation sequencing technology: current trends and advancements. Biology (Basel). 12(7), 997 (2023).

Flaherty, B. R. et al. Restriction enzyme digestion of host DNA enhances universal detection of parasitic pathogens in blood via targeted amplicon deep sequencing. Microbiome. 6(1), 164 (2018).

Huggins, L. G., Atapattu, U., Young, N. D., Traub, R. J. & Colella, V. Development and validation of a long-read metabarcoding platform for the detection of filarial worm pathogens of animals and humans. BMC Microbiol. 24 (1), 28 (2024).

Sun, H. et al. Combination of transbronchial cryobiopsy based clinic-radiologic-pathologic strategy and metagenomic next-generation sequencing for differential diagnosis of rapidly progressive diffuse parenchymal lung diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1204024 (2023).

Wang, J. Z. et al. Etiology of lower respiratory tract in pneumonia based on metagenomic next-generation sequencing: a retrospective study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1291980 (2024).

Obradovic, J. et al. Optimization of PCR conditions for amplification of GC-Rich EGFR promoter sequence. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 27(6), 487–493 (2013).

Green, M. R. & Sambrook, J. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of GC-Rich templates. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2019(2). https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot095141 (2019).

Matsui, T., Miyachi, H., Shigeta, Y. & Hirao, K. Metal-Assisted Proton Transfer in Guanine-Cytosine Pair: An Approach from Quantum Chemistry. InTech. (2012). https://doi.org/10.5772/33766

Wain-Hobson, S. The third bond. Nature. 439(7076), 539 (2006).

Smith, S., Vigilant, L. & Morin, P. A. The effects of sequence length and oligonucleotide mismatches on 5’ exonuclease assay efficiency. Nucl. Acids Res. 30(20), e111 (2002).

Kim, J. Y., Choi, J. H., Nam, S. H., Fyumagwa, R. & Yong, T. S. Parasites and blood-meal hosts of the tsetse fly in Tanzania: A metagenomics study. Parasit. Vectors. 15(1), 224 (2022).

Flaherty, B. R., Barratt, J., Lane, M., Talundzic, E. & Bradbury, R. S. Sensitive universal detection of blood parasites by selective pathogen-DNA enrichment and deep amplicon sequencing. Microbiome. 9(1), 1 (2021).

De Seram, E. L. et al. Integration of ITS-2 rDNA nemabiome metabarcoding with fecal egg count reduction testing (FECRT) reveals ivermectin resistance in multiple gastrointestinal nematode species, including hypobiotic Ostertagia ostertagi, in western Canadian beef cattle. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 22, 27–35 (2023).

De Seram, E. L. et al. Regional heterogeneity and unexpectedly high abundance of Cooperia punctata in beef cattle at a northern latitude revealed by ITS-2 rDNA nemabiome metabarcoding. Parasit. Vectors. 15(1), 17 (2022).

Workentine, M. L. et al. A database for ITS2 sequences from nematodes. BMC Genet. 21(1), 74 (2020).

Borkowski, E. A. et al. Comparison of ITS-2 rDNA nemabiome sequencing with morphological identification to quantify gastrointestinal nematode community species composition in small ruminant feces. Vet. Parasitol. 282, 109104 (2020).

Kounosu, A., Murase, K., Yoshida, A., Maruyama, H. & Kikuchi, T. Improved 18S and 28S rDNA primer sets for NGS-based parasite detection. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 15789 (2019).

Chan, A. H. E. et al. Sensitive and accurate DNA metabarcoding of parasitic helminth mock communities using the mitochondrial rRNA genes. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 9947 (2022).

Papaiakovou, M., Littlewood, D. T. J., Doyle, S. R., Gasser, R. B. & Cantacessi, C. Worms and bugs of the gut: the search for diagnostic signatures using barcoding, and metagenomics-metabolomics. Parasites Vectors. 15(1), 118 (2022).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MEST; Number NRF‑2020R1I1A2074562), the faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2023-0065), and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HI23C1527).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K. conducted laboratory experiments and analyzed the data, and drafted the original manuscript. JHC designed, supervised, and coordinated the study; he also analyzed and interpreted the data. M.K., S.Y., S.O., Y.A.L. designed, supervised, and coordinated the study. M.H.Y. designed the experiments, supervised, and coordinated the study; she also contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. T.S.Y., M.H.S. designed, supervised, and coordinated the study. J.Y.K. formulated the research aims, developed the methodology, supervised the fieldwork and coordinated study, analyzed samples and data, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and accepted the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, D., Choi, J.H., Kim, M. et al. Optimization of 18 S rRNA metabarcoding for the simultaneous diagnosis of intestinal parasites. Sci Rep 14, 25049 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76304-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76304-1