Abstract

Melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer. Hence, a better understanding of molecular mechanisms in melanoma pathogenesis is urgently needed, which provides a new insight into the therapy of melanoma. DTL gene is screened out in melanoma pathogenesis by integrated bioinformatics analysis, and its expression is validated in the tissue and cell samples of melanoma. Forced DTL expression facilitates the proliferation, invasion, migration and EMT of melanoma cells, while DTL knockdown suppresses the biological behavior of melanoma cells. In addition, DTL promotes the malignancy of melanoma in vivo. Mechanistically, BUB1 is the crucial downstream target of DTL. Reduced DTL expression suppresses BUB1 expression, while enhanced DTL expression induces BUB1 upregulation. Rescue experiments showed that growing and migrating of melanoma cells induced by DTL are partially impaired by BUB1 inhibition. In addition, the expression of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK) and the downstream transcription factor E2F1 are reduced when DTL expression is blocked. Meanwhile, BUB1 levels are decreased when the expression of p-ERK or E2F1 is repressed. Notably, the growth and migration of melanoma cells by inhibition of ERK and knockdown of E2F1 was rescued by overexpressing BUB1. DTL gene may be a prognosis marker and represent a unique potential target for melanoma patients. DTL supports the biologically malignant activity of melanoma cells via the ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to its aggressive nature and propensity for metastasis, melanoma is the most dangerous form of skin cancer1. For the past few decades, melanoma’s incidence and mortality have both been rising. Melanoma, however, cannot be completely cured. Fortunately, the molecular mechanisms involved in melanoma development have been well described. A number of biological pathways and biomarkers that contributed to the etiology of melanoma have been identified. For example, more than 50% of melanoma patients have the BRAF mutation, which stimulates MAPK signaling and promotes the progression of the disease2. The crucial pathway in melanoma pathogenesis, PI3K, has also been activated in melanoma cells3. TERT promoter mutations occur in most melanoma patients4. P53 has a central role in skin pigmentation and may impact on melanoma at all stages5. Although a great deal of research has attempted to elucidate the molecular process in melanoma development over the past few decades, a better understanding of molecular mechanisms in melanoma pathogenesis is urgently needed.

In order to gain new understanding of the underlying mechanisms in carcinogenesis and to identify biomarkers for predicting patient prognosis, bioinformatics analysis and gene expression profiling are regarded to be useful approaches6,7. New hints for cancer pathogenesis may be discovered by reanalyzing and integrating the accessible data as more and more data in public databases. As an illustration, Xu Z and colleagues discovered important genes that may serve as prospective targets for the detection and treatment of ovarian cancer8. Similarly, Bi D and colleagues found hub genes linked to bladder cancer by combining network analysis with gene expression patterns9. In melanoma, Wei C and colleagues’ bioinformatics-based investigation identified increased MFSD12 as a significant activator of tumor cell proliferation and a possible treatment target10. Molecular-based targeted therapy could serve as promising therapies for cancer treatment. In our study, we found that DTL gene may play a crucial role in melanoma progression via bioinformatics analysis and gene expression profiling.

Denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (DTL), a homolog of E3 ubiquitin ligase, functions as a substrate receptor for Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) and is a member of the DCAF protein family containing WD40 repeats11. According to earlier studies, DTL was implicated in the regulation of cell cycle and DNA damage repair, and a critical regulator of genome stability and cell cycle progression12,13. Abnormal expression of DTL was found in several cancer types, including breast cancer, Ewing sarcoma, gastric cancer, ovarian surface epithelial cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and melanoma14,15,16,17,18,19. The biological function and molecular processes of DTL in melanoma remain unknown, despite the evaluation of DTL level in melanoma.

In our study, we examined the expression and biological roles of DTL in melanoma. The finding demonstrated that overexpression of DTL in melanoma samples is associated with a poor prognosis. DTL encourages the malignant biological progression of melanoma both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanically, DTL facilitates the biological malignancy of melanoma cells via the ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis. Thus, DTL has the potential to be a novel diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for melanoma patients.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

Including criteria are the following: (1) cancer type is melanoma; (2) The samples are from human; (3) sequencing samples are tissue samples; and (4) there are more than 25 samples. Excluding criteria are the following: (1) cancer type is non-melanoma; (2) The samples are not from human; (3) sequencing samples are cell or blood samples; (4) the number of samples is less than 25. Finally, four GEO datasets (GSE7553, GSE15605, GSE46517 and GSE114445) are selected. GSE7553, which is based on the GPL570 platform (HG-U133_Plus_2, Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array), contains 56 melanoma and 4 benign samples; GSE15605, which is based on the GPL570 platform (HG-U133_Plus_2, Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array), contains 58 melanoma and 16 benign samples; GSE46517, which is based on the GPL96 platform (HG-U133A, Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array), contains 104 melanoma and 16 benign samples; and GSE114445, which is based on the GPL570 platform (HG-U133_Plus_2, Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array), contains 16 melanoma and 11 benign samples. GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) is used to find differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between melanoma and nevus samples20. An adjusted p value < 0.01 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 are set as the cutoff criteria. The online tool Venn (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) is applied to obtain the overlapping DEGs (ODEGs) in two or more datasets.

Analysis of DEG expression and survival

GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) is used to analyze the RNA sequencing expression data from TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) and the GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) project in accordance with a standard processing pipeline21, and analyze the relationship between DEGs and the overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) of patients. The p values are shown on the plots.

Tissue samples

Paraffin sections of melanoma tissues and normal skin tissues were acquired from outpatient and inpatient surgery patients at Union Hospital, Tongji Medical college, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. All samples were diagnosed as melanoma by pathological analysis and tissue confirmation. Before a complete excision, no one received radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The clinical stage of each tumor was determined according to the TNM staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and IUCC (8th edition)22. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Tongji Medical college, Huazhong University of Science (the approval number is UHCT-IEC-SOP-016-03-01), all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Cell culture

The human melanoma cell lines A2058, SK-MEL-2, SK-MEL-28 and MUM-2B were purchased from Shanghai Jinyuan Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). A2058 is grown in DMEM medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, #10270-106, Gibco, USA) at 37 °C, 5%CO2, while SK-MEL-2, SK-MEL-28 and MUM-2B are grown in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C, 5%CO2. Normal human epidermal melanocyte (HEM) was bought from ATCC cell bank, growing in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C, 5%CO2.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining

Briefly, the tissue sections are deparaffinized, rehydrated, antigen retrievaled, inactivate endogenous peroxidase and block nonspecifc antigen-binding according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the slides are incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. After being washed with PBS (pH 7.6), the slides are treated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 1 h at room. After that, the slides are stained with diaminobenzidine and hematoxylin (Servicebio, China). IHC photos were taken, and the IHC results were quantified by Image J software. the primary antibodies are as followed: anti-DTL (bs-7935R, Bioss, China), anti-Ki67 (sc-23900, Santa Cruz, USA) and anti-CD31 (sc-376764, Santa Cruz, USA).

Lentiviral transfection and small interfering RNA (siRNA) interference

The DTL overexpression lentiviral plasmid was bought from Hanbio Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The shRNA lentiviral plasmids of DTL were obtained from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Lentiviral vectors were packaged in Hanbio Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). To obtain suitable fluorescence expression, the transfected cells were selected with puromycin (ST551-10 mg, Beyotime, China) at a concentration of 2 µg/ml. Quantative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and western blotting were used to verify the transfection efficiency.

SiRNA sequences targeting BUB1 and E2F1 were purchased from Tsingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). 30–50% confluence of cells was transfected with siRNA or siNC using EndoFectin™ Max transfection reagent (EF013, GeneCopoeia). The sequences of siRNAs were shown in Additional file 1: Supplementary Table S1.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR assays

RNA was extracted from cell lines with TRIzol reagent (Vazyme, China), then was reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qRT-PCR (+ gDNA wiper) (R323-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the standard instructions. QRT-PCR was carried out on Step One plus real-time PCR system using 2x SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (B21202, Bimake, USA). The running conditions were 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C and 30 s at 72 °C, and then for a melting curve, 15 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, and 15 s at 95 °C. Relative quantification was normalized to ß-actin. The primer sequences were provided in Additional file 2: Supplementary Table S2.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed following the standard protocols described previously. Primary antibodies against DTL (bs-7935R, Bioss, China), ß-actin (66009-1-Ig, ProteinTech Group), BUB1 (DF6698, Affinity Biosciences, USA), E2F1 (A5693, Bimake, USA), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4370, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (4695, Cell Signaling Technology, USA), Ki67 (sc-23900, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), CD31 (sc-376764, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), E-cadherin (10204-T52, Sino Biological, China), Vimentin (100254-R001, Sino Biological, China), Snail and Slug (bs-11961R, Bioss, China), ZEB1 (21544-1-AP, ProteinTech Group), N-cadherin (sc-8424, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA), CDC20 (10252-1-AP, ProteinTech Group) and phospho-CDC20 (8038, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) were used. The second antibodies conjugated with HRP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used, and the blots were detected by a chemiluminescent detection system (Pierce ECL Substrate Western Blot Detection System; Thermo Scientifc, Rockford, MA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining were carried out as described previously. Briefly, cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% bovine serum albumin, and then were incubated with the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing by PBS, cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (GB21303, Servicebio, China) for 1 h at room. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (G1012, Servicebio, China). All images were captured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). Primary antibodies against E-cadherin (R22490, Zen-bioscience, China), Vimentin (R22775, Zen-bioscience, China), N-cadherin (sc-8424, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) were used. The second antibodies conjugated with HRP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used.

CCK8 cell proliferation assay

The CCK-8 cell proliferation assay was performed according to a previous study23. 1000 cells were seeded into per well of 96-well plates. At indicated time point, cells in each well were treated with 10 µl of the Cell Counting Kit solution (APExBIO, Houston, USA) and further incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. And the absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader, then the proliferation rate of cells was quantified.

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining

Proliferating cells were valued by BeyoClickTM EdU Cell Proliferation Kit (C0075S, Beyotime, China). In brief, proliferating cells were incubated with Edu working solution (10 µM) for 2 h at 37 °C. After incubation, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Then, cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X100 for 15 min, and washed with PBS for 3 min three times. Next, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33,342 for 10 min. Images were captured with a laser scanning microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Colony formation assay

The colony formation assay was performed according to a previous study24. 300 cells were seeded in each well of six-well plate, and the culture medium was refreshed every 3 days. When the cells were cultured for 14 days or the number of cells in most single clones was greater than 50, the culture stopped. After the culture finished, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, and stained with crystal violet for 15 min.

Transwell assays

Cell invasion or migration activity was observed in 8.0-µm pore-size 24-well transwell insert chambers (#3422, Corning, USA) with the former was coated with MaxGelTM ECM (#E0282, Sigma-Aldrich) and the latter was not. 4 × 104 melanoma cells/well were seeded into the upper chamber with serum-free medium and medium with 10% FBS was added into the lower chamber. After incubation for 24 h, the non-invasive or non-migrated cells of the upper chamber were wiped out with a cotton swab. Then cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and stained with crystal violet for 20 min. Migration cells were counted in five randomly chosen fields.

Wound healing assays

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and cultured in full medium until 80% density. Cell monolayers were scratched with a sterile 200-µl pipette tip. The non-adherent cells were removed by washing them with sterile PBS. Six-well plates were filled with medium devoid of FBS. Cells were cultured and imaged at 0, 24, and 48 h using a microscope. The migration rate of cells in each well were analyzed with Image J software.

RNA-sequencing

The cell lines (Sk-Mel-2 and Sk-Mel-28) loaded with DTL overexpression and blank virus were delivered to Shanghai Biotree Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd for RNA-sequencing. The sequencing process includes total mRNA extraction, RNA quality assessment, full transcriptome library construction, sequencing and raw data quality control.

In vivo tumorigenesis

All animal studies were approved by Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology and performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (IACUC number is 3287). The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). Briefly, the female BALB/c nude mice aged at 4–6 weeks were subcutaneously injected with 107 tumor cells suspended in 150 ml of PBS. Tumor volume was measured every five days and mice were sacrificed by carbon dioxide euthanasia until the end of the protocol. Tumor volume was calculated following formula: V = (L × W2)/2. Every Tumor’s weight was measured in grams. In addition, the tumors of mice were sectioned for IHC staining.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism 9 Software (https://www.graphpad.com/). The data were presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis between two groups were compared using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Statistics analysis among multiple groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P value < 0.05 was considered to be significantly different.

Results

Upregulated DTL is negatively associated with OS and DFS

There are 56 melanoma and 4 normal samples in GSE7553, 58 melanoma and 16 normal samples in GSE15605, 104 melanoma and 16 normal samples in GSE46517, and 16 melanoma and 11 normal samples in GSE114445. GEO2R (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) is utilized to identify DEGs between melanoma and nevus samples. An adjusted p value < 0.01 and |log2FC| ≥ 1 are set as the cutoff criteria. GSE7553 contains 1856 DEGs, namely, 389 upregulated genes and 1467 downregulated genes; GSE15605 contains 3136 DEGs, namely, 1278 upregulated genes and 1858 downregulated genes; GSE46517 contains 882 DEGs, namely, 275 upregulated genes and 607 downregulated genes; GSE114445 contains 710 DEGs, namely, 446 upregulated genes and 264 downregulated genes (Fig. 1A). There are 94 ODEGs in GSE7553, GSE15605, GSE46517 and GSE114445 (Fig. 1B). Across four GEO datasets, there are 20 upregulated genes and 69 downregulated genes among these ODEGs. Among the 69 downregulated genes, levels of four genes (TNFRSF25, CRIP1, SYT17, CA12) are favorably linked with patients’ OS but not with DFS (Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. S1). Among the 20 upregulated genes, DTL, TIMP2, CCNB1 and TPX2 levels are substantially inversely linked with the patient’s OS (Fig. 1C, Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. S1). Notably, only DTL expression is also negatively correlated with DFS (Fig. 1D).

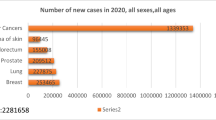

To further explore the functions of DTL in diverse carcinogenesis, we examined DTL expression in the majority of human malignancies using GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html). The results showed that DTL is elevated in most cancer types, including melanoma (Fig. 1E), supporting the idea that DTL may function as an oncogene in the development of malignancies. Moreover, high expression of DTL in melanoma is confirmed in TCGA dataset (Fig. 1F). These analyses demonstrated that elevated DTL, which is negatively associated with OS and DFS, may contribute to melanoma pathogenesis.

Elevated DTL expression is associated with poor prognosis in melanoma patients

The expression of DTL was examined in the tissue and cell samples of melanoma. In cell samples, DTL levels in melanoma cell lines are higher than that in HEM (Fig. 1G, Additional file 7). In tissue samples, DTL protein levels in melanoma tissues are substantially higher than that in normal skin tissues (Fig. 1H). Moreover, DTL expression is positively related to clinical stage of melanoma patients (Fig. 1H). In addition, the clinical data of 417 individuals with melanoma were retrieved from TCGA database. After removing the partial incomplete data, the clinical data of 261 melanoma patients were finally analyzed. The tumor samples were subsequently categorized into two groups based on DTL expression, resulting in 134 patients with high expression and 127 patients with low expression. The association between DTL expression and clinical parameters of melanoma patients is presented in Table 1. Our findings revealed a positive correlation between high DTL expression and advanced Clark level (p = 0.0257), greater Breslow depth (p = 0.0032), as well as higher incidence of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.0255) (Table 1). The aforementioned results reveled that DTL is high expressed in melanoma and we thus hypothesize that DTL may be crucial in melanoma pathogenesis.

Elevated DTL expression is related to the poor prognosis of melanoma. (A) Several DEGs in GSE7553, GSE15605, GSE46517 and GSE114445. (B) 94 ODEGs in the four GEO datasets. (C,D) Elevated DTL was negatively associated with OS and DFS of melanoma patients. (E) DTL expression was elevated in most cancer types. (F) High expression of DTL in melanoma was confirmed in TCGA dataset. (G) DTL levels in melanoma cell lines were higher than that in HEM. (H) Elevated DTL expression in melanoma tissues was positively related to clinical stage of melanoma patients (n = 3). N: normal skin tissues. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. ACC adrenal cortical carcinoma, BLCA bladder cancr, BRCA breast cancer, CESC cervical squamous cell carcinoma, CHOL cholangiocarcinoma, COAD colon adenocarcinoma, DLBC diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, ESCA esophageal carcinoma, GBM glioblastoma, HNSC head & neck squamous cell carcinoma, KIRP kidney papillary cell carcinoma, LAML acute myeloid leukemia, LIHC liver hepatocellular carcinoma, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, LUSC lung squamous cell carcinoma, OV ovarian cancer, PAAD pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PCPG pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, PRAD prostate adenocarcinoma, READ rectum adenocarcinoma, SARC sarcoma, SKCM skin cutaneous melanoma, STAD stomach adenocarcinoma, THCA thyroid cancer, THYM thymoma, UCEC uterine corpus endometrioid carcinoma, UCS uterine carcinosarcomas.

Forced DTL expression promotes oncogenicity of melanoma cells

To determine the biological function of DTL in melanoma development, Sk-Mel-2 and Sk-Mel-28 cell lines with stable over-expression of DTL (designated as Sk-Mel-2-DTL and Sk-Mel-28-DTL) were established. The forced expression of DTL was validated by appropriate fluorescence expression, qRT-PCR and western blot analysis (Fig. 2A–C and a–c, Additional file 7). Subsequently, the effect of DTL overexpression on melanoma cell proliferation was assessed by CCK8 proliferation assay, EdU staining and colony formation assay. Forced expression of DTL enhances the proliferative capability of melanoma cells compared with the control cells (Fig. 2D–F, d–f). Moreover, enhanced expression of DTL also exhibits a significant increase in prompting the migration and invasion of cancer cells (Fig. 2G–I, g–i). In addition, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is closely related to migration and invasion of cancer cells, was also examined by western blot and immunofluorescence staining. Our results showed that elevated DTL prompts EMT with enhancing the level of mesenchymal biomarker (N-cadherin, vimentin, Snail, Slug and ZEB1) and decreasing the expression of epithelial biomarker (E-cadherin) (Fig. 2J–K and j–k, Additional file 7).

Forced expression of DTL promotes oncogenicity of melanoma cells. ((A−C) and (a−c)) The forced expression of DTL was validated by appropriate green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression (C and c), qPCR (A and a) and western blot analysis (B and b). ((D–F) and (d–f)) Forced expression of DTL enhanced the proliferative capability of melanoma cells by CCK8 proliferation assay (D and d), colony formation (E and e) assay and EdU staining (F and f). ((G–I) and (g–i)) Enhanced expression of DTL also exhibited a significant increase in prompting the invasion (G and g) and migration ((H,I) and (h,i)) of cancer cells. ((J,K) and (j,k)) Elevated DTL prompted EMT by western blot (J and j) and immunofluorescence staining (K and k). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Depleted DTL expression suppresses oncogenicity of melanoma cells

DTL expression was depleted in Sk-Mel-2 and Sk-Mel-28 cells by siRNA-based approach. There were there siDTL sequences, we chose si-DTL#3 sequence with the best effect of DTL knockdown for lentiviral packaging (Additional file 4: Supplementary Fig. S2, Additional file 7), which were designated as Sk-Mel-2-shDTL and Sk-Mel-28-shDTL. The depletion efficiency of DTL was valued by suitable fluorescence expression, qPCR and western blot analysis (Fig. 3A–C and a–c, Additional file 7). It was observed that depletion of DTL significantly decreases the proliferation, invasion and migration of melanoma cells, as well as inhibited EMT (Fig. 3D–K and d–k, Additional file 7).

DTL depletion suppresses oncogenicity of melanoma cells. ((A−C) and (a−c)) The depleted expression of DTL was validated by appropriate fluorescence expression (C and c), qPCR (A and a) and western blot analysis (B and b). ((D–F) and (d–f)) Depleted expression of DTL inhibited the proliferative capability of melanoma cells by CCK8 proliferation assay (D and d), colony formation (E and e) assay and EdU staining (F and f). ((G–I) and (g–i)) Depleted expression of DTL also exhibited the decreased invasion (G and g) and migration ((H,I) and (h,i)) of cancer cells. ((J,K) and (j,k)) Depleted DTL suppressed EMT by western blot (J and j) and immunofluorescence staining (K and k). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

DTL promotes the malignancy of melanoma in vivo

A mouse xenograft model was established to ascertain whether forced DTL expression accelerated melanoma growth in vivo. At the termination of the experiment, we observed that forced DTL expression greatly enhances the size and weight of xenograft tumor (Fig. 4A). Additionally, xenografts derived from Sk-Mel-28-DTL cells show an increase in the percentage of Ki67- and CD31-positive cells by IHC staining, showing that there are more proliferating tumor cells and more vasculature formation to support tumor cells’ distant migration (Fig. 4C). Contrarily, the volume and weight of the xenograft tumor are considerably decreased when DTL expression was diminished (Fig. 4B). And, xenografts derived from Sk-Mel-28-shDTL cells exhibits a decrease in the percentage of Ki67- and CD31-positive cells, showing that there are less proliferating tumor cells and less vasculature formation (Fig. 4C).

DTL promotes the malignancy of melanoma in vivo. (A) Forced DTL expression greatly enhanced the size and weight of xenograft tumor. (B) Depleted DTL considerably decreased the volume and weight of the xenograft tumor. (C) IHC results indicated that xenografts derived from Sk-Mel-28-DTL cells had a higher percentage of Ki67- and CD31-positive cells compared to Sk-Mel-28-shDTL. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. NC normal control.

Identifying BUB1 as the key downstream target gene of DTL

To study the mechanism by which DTL encourages the malignant biological development of melanoma, The cell lines (Sk-Mel-2 and Sk-Mel-28) with DTL overexpression and blank virus were subjected to RNA-sequencing. We focused the top 10 genes based on the correlation coefficient ranking of DTL and several genes in ualcan-melanoma datasets (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) (Fig. 5A). Notably, we found that the levels of BUB1 mRNA, at the 7th ranking, are elevated both in Sk-Mel-2-DTL and Sk-Mel-28-DTL cells with a fold change more than 1 in the data of RNA-sequencing (Additional file 5: Supplementary Table S3). And, GEPIA evaluated the relationship between DTL and the BUB1 gene, finding that R = 0.75 (Fig. 5B), which is not significantly different from 0.81. In addition, the level of BUB1 protein was validated by western blot (Fig. 5C, Additional file 7). Moreover, BUB1 is aberrantly expressed in human malignancies (Fig. 5D), implying that BUB1 may have an important role in the carcinogenesis. To further investigate the role of BUB1 in melanoma pathogenesis, the gene expression profile of melanoma patients from TCGA dataset was analyzed, showing that BUB1 is high expressed in melanoma (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, correlation between BUB1 and cell proliferation-related genes (such as ki-67 and PCNA) in melanoma datasets was also examined. The correlation scatter plots indicated that BUB1 expression is favorably correlated with the expression of ki-67 and PCNA, with R = 0.7 and 0.58, respectively (Fig. 5F). Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated that BUB1 is implicated in the development and progression of numerous malignancies, such as bladder cancer, breast cancer25,26, and therefore we assumed that BUB1 may also be crucial in melanoma pathogenesis. Our data demonstrated that the level of BUB1 protein is elevated when DTL is forced-expressed, whereas BUB1 expression is obviously decreased after DTL expression is inhibited (Fig. 5C and G, Additional file 7). These results implied that BUB1 is a key downstream target of DTL in melanoma pathogenesis.

BUB1 is identified out as the key downstream target gene of DTL. (A and C) The level of BUB1, at the 7th ranking (A), was validated by western blot (C). (B) The relationship between DTL and the BUB1 gene was evaluated by GEPIA. (D) BUB1 was aberrantly expressed in human malignancies. (E) BUB1 was high expressed in melanoma from TCGA datasets. (F) BUB1 expression was favorably correlated with the expression of ki-67 and PCNA. (G) BUB1 expression was obviously decreased after DTL expression was inhibited. *P < 0.05. ACC adrenal cortical carcinoma, BRCA breast cancer, CHOL cholangiocarcinoma, DLBC diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, GBM glioblastoma, KIRP kidney papillary cell carcinoma, LUAD lung adenocarcinoma, OV ovarian cancer, PCPG pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, READ rectum adenocarcinoma, SKCM skin cutaneous melanoma, THYM thymoma, UCS uterine carcinosarcomas.

BUB1 mediates the growth and metastasis of melanoma cells

Next, the biological function of BUB1 in melanoma cells was validated. Three sequences of siRNAs were designed to downregulate BUB1 expression, and the knockdown effectiveness was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 6A, Additional file 7). SiBUB1-1# and siBUB1-3# with greater knockdown effectiveness were employed for additional investigations. Growth curve analysis, clone formation assay and EDU staining revealed that BUB1 knockdown drastically suppresses the proliferated ability of melanoma cells (Fig. 6B–D). In addition, the results of transwell and would healing suggested that the invasion and migration of melanoma cells are also hindered when BUB1 is downregulated (Fig. 6E,F). Our data indicated that BUB1 could promote the proliferation, invasion and migration of melanoma, which is consistent with the roles of DTL in melanoma pathogenesis. Combined with the consistent expression of DTL and BUB1 in melanoma cells, we speculated that they may play a synergistic role in the pathogenesis of melanoma.

BUB1 mediates the growth and metastasis of melanoma cells. (A) BUB1 expression was knocked down by siRNA approach. (B–D) BUB1 knockdown drastically suppressed the proliferated ability of melanoma cells by growth curve analysis (B), EDU staining (C) and clone formation assay (D). (E,F) The invasion (E) and migration (F) of melanoma cells were hindered when BUB1 was downregulated. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

BUB1 participates in DTL-induced growth and migration of melanoma cells

To confirm the function of BUB1 in DTL-mediated growth and migration of melanoma cells, we transiently transfected BUB1 siRNA (siBUB1-1# and siBUB1-3#) into Sk-Mel-2-DTL and Sk-Mel-28-DTL cells. BUB1 knockdown reduces the proliferated ability of melanoma cells (Fig. 7A). Consistent with the results of the proliferation assay, BUB1 inhibition partially reverses the impact of DTL on the migration of melanoma cells (Fig. 7B). There, BUB1 is involved in DTL-induced growth and migration of melanoma cells.

BUB1 participates in DTL-induced growth and migration of melanoma cells. (A) BUB1 knockdown reduced the proliferated ability induced of melanoma cells by DTL. (B) BUB1 inhibition partially reversed the impact of DTL on the migration of melanoma cells. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001. *DTL vs. DTL + siBUB1-1/3# and DTL vs. NC, #: NC vs. NC + siBUB1-1/3#.

DTL prompts the growth and migration of melanoma cells via ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis

Our data indicated that DTL prompts the invasion and migration of melanoma cells (Fig. 2G-I and g-i), and the ERK signaling pathway plays a crucial role during the migration and invasion of cancer cells27,28. Hence, we investigated whether ERK signaling has a role in the tumor-promoting characteristics of DTL in melanoma. Western blot analysis indicated that when DTL expression is repressed, p-ERK level is reduced (Fig. 8A, Additional file 7), indicating that ERK signaling may be involved in the pro-tumorigenic activity of DTL. However, the same trend is not observed in Sk-Mel-2-DTL and Sk-Mel-28-DTL cell lines. This may be due to parent cells display p-ERK at high levels, which prevents us from detecting higher level of DTL expression in Sk-Mel-2/28-DTL cell lines. Consequently, we decided to use parent cells and the Sk-Mel-2/28-shDTL cell line for further experiments. To confirm the involvement of the ERK signaling in tumor promotion by DTL in melanoma, parent cells were treated with two specific MEK inhibitors (U0126 and PD0325901). The results of western blot showed that when MEK inhibitors are added, the level of p-ERK and DTL target gene BUB1 are both decreased, and the phosphorylation state of CDC20, a known downstream factors of BUB1 kinase, is also inhibited (Fig. 8B, Additional file 7). The transcription factor E2F1, a downstream component of the ERK signaling pathway, is intimately linked to the growth of cancer cells29,30. However, the study of DTL and E2F1 in melanoma is limited. Thus, we also examined E2F1 level. Our data indicated that E2F1 expression is also suppressed when MRK inhibitors are added or DTL expression is reduced (Fig. 8B, Additional file 7). Consistently, the proliferation and migration of melanoma cells are suppressed when parent cells are treated with MEK inhibitors, just as they are in Sk-Mel-2/28-shDTL cell lines (Fig. 8C-D, Additional file 6: Supplementary Fig. S3B). These results indicated that ERK signaling has a role in the growth and metastasis induced by DTL during the development of melanoma. To examine whether ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis is important in the pathogenesis of DTL in melanoma, BUB1 was overexpressed (Additional file 6: Supplementary Fig. S3A). Notably, we found that BUB1 overexpression partially impedes the growth and migration inhibition of MEK inhibitors on melanoma cells (Fig. 8C-D), which conformed ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis.

To explore whether E2F1 was involved in the regulation of DTL in the pathogenesis of melanoma, E2F1 expression is depleted by siRNA technology. SiE2F1-1# and siE2F1-2# were utilized for subsequent tests (Fig. 8E, Additional file 7). In addition, we observed that when E2F1 expression is suppressed, the expression of BUB1 and phosphorylated CDC20 are likewise repressed (Fig. 8E, Additional file 7). Moreover, our data suggested that E2F1 inhibition greatly inhibits the proliferation and migration of parent cells, much like it does in Sk-Mel-2/28-shDTL cell lines (Fig. 8F, Additional file 6: Supplementary Fig. S3C). These results indicated that the transcription factor E2F1 is also involved in the proliferation and migration of melanoma cells induced by DTL in the progression of melanoma. Consistently, we found that BUB1 overexpression partially impedes the growth and migration suppression of E2F1 inhibition on melanoma cells (Fig. 8F, Additional file 6: Supplementary Fig. S3C), which conformed ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis.

DTL prompts the growth and migration of melanoma cells via ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis. (A) When DTL expression was repressed, p-ERK level was reduced. (B) When MEK inhibitors were added, the level of p-ERK, E2F1, BUB1 and downstream CDC20 phosphorylation were decreased. (C,D) The proliferation and migration of melanoma cells were suppressed when parent cells were treated with MEK inhibitors, and BUB1 overexpression partially impedes the growth and migration inhibition of MEK inhibitors on melanoma cells. (E) When E2F1 expression was suppressed, the expression of BUB1 and phosphorylated CDC20 were likewise repressed. (F) E2F1 inhibition greatly inhibited the proliferation parent cells, and BUB1 overexpression partially impedes the growth suppression of E2F1 inhibition on melanoma cells. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. #MEK inhibitors (U0126 and PD0325901) or siE2F1 (siE2F1-1# and siE2F1-2#) vs. them + BUB1 overexpression. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, ####P < 0.0001.

Discussion

It has been widely utilized to uncover certain possible diagnostic and therapeutic targets in various cancers through the use of bioinformatics and gene expression profiling31,32. In the current study, there are 94 ODEGs (20 upregulated ODEGs and 69 downregulated ODEGs) obtained from the GSE7553, GSE15605, GSE46517 and GSE114445 datasets, which are chosen for reanalysis. Interestingly, only 8 ODEGs are significantly related to melanoma patients’ survival. Nevertheless, only the expression of DTL gene among upregulated genes has a negative correlation with melanoma patients’ OS and DFS. A recent study showed that DTL is a predictive biomarker and promoted bladder cancer progression33. Moreover, DTL accelerated cell development and was linked to poor survival in cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and cervical adenocarcinoma34,35,36. However, the precise function and mechanism of DTL in the etiology of melanoma are unclear. Thus, we focused on DTL gene in melanoma pathogenesis. In our research, we discovered that DTL encourages melanoma cell proliferation, invasion and migration, which results in a poor prognosis. These results indicated that DTL may play a crucial role in melanoma tumorigenesis.

DTL gene, also namely as CDT2/RAMP/DCAF2/L2DTL, is located on chromosome 1q32, and this area is often amplified in human solid cancers37. DTL could facilitate the epigenetic modification and degradation of several genes, such as CDT138,39,40 and p2141,42,43, indicating that DTL may be a key player in human malignancies. In melanoma samples, we found that DTL is high expressed, just like that an open access online database showed. A series of experiments confirmed that forced DTL expression increases the malignant biological activity of melanoma cells. On the other hand, depletion of DTL suppresses oncogenicity of melanoma cells. These results are in line with studies on DTL in most human malignancies. Herein, our research provided evidence that DTL functions as an oncogene in melanoma.

To further explore the precise mechanism of DTL in melanoma tumorigenesis, Sk-Mel-2-DTL and Sk-Mel-2-NC, Sk-Mel-28-DTL and Sk-Mel-28-NC lines were evaluated by RNA-sequencing. Fortunately, we pinpointed the vital downstream target BUB1, which is involved in the regulation of DTL in melanoma carcinogenesis. BUB1 (Budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1), a mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine kinase, serves an essential role in establishing the mitotic spindle checkpoint, aligning chromosomes44, and the accurate partitioning of chromosomes45,46. In a number of cancer types, including liver cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, and gastric cancer, BUB1 may act as an oncogene or tumor suppressor gene47,48,49,50,51. However, the biological function of BUB1 in melanoma is yet unknown. Our finding indicated that BUB1 downregulation suppresses the biological behavior of melanoma cells. The subsequent functional experiments uncovered that BUB1 knockdown partially impairs phenotypic changes in Sk-Mel-2/28-DTL cell lines. We discovered BUB1 to be a key target engaged in the process of DTL mediating the growth, invasion and metastasis of melanoma cells. Above all, we determined that BUB1 has a role in DTL’s carcinogenic function in melanoma. However, the precise regulatory mechanisms by which DTL regulating BUB1 have not yet been completely identified.

Our study revealed that DTL contributes to the invasion, migration and the related EMT process, so we attempted to examine the phosphorylation of ERK signaling pathway, which plays a significant part in the invasion and migration of cancer cells27,28. Our results showed that when DTL expression is repressed, the levels of p-ERK and downstream molecule E2F1 reduce, suggesting that the ERK/E2F1 signaling may be involved in the pro-tumorigenic actions of DTL. E2F1, belonging to E2F family, is most extensively studied in melanoma. Nevertheless, the function of E2F1 in the etiology of melanoma is debatable, because E2F1 can serve as activator or inhibitor in the carcinogenesis52,53. The transcription of particular genes is inappropriately activated by the transcription factor E2F1 to speed up the cell cycle process53. In addition, E2F1 prompts the invasion and migration of cancer cells through regulating MYLK transcription54. Moreover, high E2F1 mRNA expression is present in some tumors with high grades, which is assumed to be connected to the poor survival55. In our study, we found that ERK/E2F1 signaling takes part in the growth and migration of melanoma cells induced by DTL. To examine the complex regulatory mechanisms of ERK/E2F1 signaling in the malignant behavior of melanoma cells induced by DTL, tumor cells were treated with specific MEK inhibitors and siRNA E2F1 or without. In this work, MEK inhibitors and E2F1 suppression reduce parent cell growth and migration in a manner similar to that shown in Sk-Mel-2/28-shDTL cell lines. Notably, BUB1 overexpression partially impedes the growth and migration inhibition of MEK inhibitors or E2F1 suppression on melanoma cells, which supported that the ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis is important in the growth and migration of melanoma cells induced by DTL.

Yet, there are still many shortcomings in our study. We only examined the phosphorelated state of ERK, other pathways (such as STAT’s phosphorelated state) which may be changed were not examined. Moreover, we just examined BUB1 expression without observing any abnormalities in spindle assembly checkpoints (e.g., chromosomal missegregation). Further investigation need to be done in the future.

Conclusions

In our study, we established the biological functions of DTL and its regulation mechanism in melanoma. Through our research, we found that DTL is high expressed in melanoma, which is linked to a poor prognosis. Mechanically, DTL facilitates the malignant biological behavior of melanoma cells via the ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the BioProject ID PRJNA1097771 repository [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1097771].

Change history

23 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11486-w

References

Mishra, H. et al. Melanoma treatment: from conventional to nanotechnology. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 144, 2283–2302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2726-1 (2018).

Amaral, T. et al. MAPK pathway in melanoma part II-secondary and adaptive resistance mechanisms to BRAF inhibition. Eur. J. Cancer 73, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.012 (2017).

Chamcheu, J. C. et al. Role and therapeutic targeting of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in skin cancer: A review of current status and future trends on natural and synthetic agents therapy. Cells 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8080803 (2019).

Horn, S. et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science 339, 959–961. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230062 (2013).

Lu, M. et al. Restoring p53 function in human melanoma cells by inhibiting MDM2 and cyclin B1/CDK1-phosphorylated nuclear iASPP. Cancer Cell 23, 618–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.013 (2013).

Chen, Y., Qi, C., Xia, L. & Li, G. Identification of novel genetic etiology and key molecular pathways for seminoma via network-based studies. Int. J. Oncol. 51, 1280–1290. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2017.4092 (2017).

Peng, J. et al. High-throughput sequencing and co-expression network analysis of lncRNAs and mRNAs in early brain Injury following experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage. Sci. Rep. 7, 46577. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46577 (2017).

Xu, Z. et al. Identification of candidate biomarkers and analysis of prognostic values in ovarian cancer by integrated bioinformatics analysis. Med. Oncol. 33, 130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-016-0840-y (2016).

Bi, D., Ning, H., Liu, S., Que, X. & Ding, K. Gene expression patterns combined with network analysis identify hub genes associated with bladder cancer. Comput. Biol. Chem. 56, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.04.001 (2015).

Wei, C. Y. et al. Bioinformatics-based analysis reveals elevated MFSD12 as a key promoter of cell proliferation and a potential therapeutic target in melanoma. Oncogene 38, 1876–1891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0531-6 (2019).

Nishitani, H. et al. Two E3 ubiquitin ligases, SCF-Skp2 and DDB1-Cul4, target human Cdt1 for proteolysis. EMBO J. 25, 1126–1136. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601002 (2006).

Rossi, M. et al. Regulation of the CRL4(Cdt2) ubiquitin ligase and cell-cycle exit by the SCF(Fbxo11) ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 49, 1159–1166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.004 (2013).

Abbas, T. & Dutta, A. CRL4Cdt2: master coordinator of cell cycle progression and genome stability. Cell Cycle 10, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.10.2.14530 (2011).

Ueki, T. et al. Involvement of elevated expression of multiple cell-cycle regulator, DTL/RAMP (denticleless/RA-regulated nuclear matrix associated protein), in the growth of breast cancer cells. Oncogene 27, 5672–5683. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2008.186 (2008).

Mackintosh, C. et al. 1q gain and CDT2 overexpression underlie an aggressive and highly proliferative form of ewing sarcoma. Oncogene 31, 1287–1298. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2011.317 (2012).

Li, J. et al. Identification of retinoic acid-regulated nuclear matrix-associated protein as a novel regulator of gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 101, 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605202 (2009).

Pan, W. W. et al. Ubiquitin E3 ligase CRL4(CDT2/DCAF2) as a potential chemotherapeutic target for ovarian surface epithelial cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 29680–29691. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.495069 (2013).

Pan, H. W. et al. Role of L2DTL, cell cycle-regulated nuclear and centrosome protein, in aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Cycle 5, 2676–2687. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.5.22.3500 (2006).

Yang, L. et al. Identification of a functional polymorphism within the 3’-untranslated region of denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase homolog associated with survival in acral melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer 118, 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.006 (2019).

Davis, S. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: a bridge between the Gene expression Omnibus (GEO) and BioConductor. Bioinformatics 23, 1846–1847. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm254 (2007).

Tang, Z. et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W98–W102. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx247 (2017).

Barreiro-Capurro, A. et al. Differences in cutaneous melanoma survival between the 7th and 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). A multicentric population-based study. Eur. J. Cancer 145, 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.036 (2021).

Cai, J. B. et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 accelerates p14(ARF) degradation by deubiquitinating thyroid hormone receptor-interacting protein 12 and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology 61, 1603–1614. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.27682 (2015).

Wei, C. et al. Upregulation of UHRF1 promotes the progression of melanoma by inducing cell proliferation. Oncol. Rep. 39, 2553–2562. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.2018.6356 (2018).

Jiang, N. et al. BUB1 drives the occurrence and development of bladder cancer by mediating the STAT3 signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 40, 378. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-021-02179-z (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Biological and clinical significance of MAD2L1 and BUB1, genes frequently appearing in expression signatures for breast Cancer prognosis. PLoS One. 10, e0136246. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136246 (2015).

Sheng, W. et al. Musashi2 promotes EGF-induced EMT in pancreatic cancer via ZEB1-ERK/MAPK signaling. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-020-1521-4 (2020).

Gao, S., Hu, J., Wu, X. & Liang, Z. PMA treated THP-1-derived-IL-6 promotes EMT of SW48 through STAT3/ERK-dependent activation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 108, 618–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.067 (2018).

Sloan, R. S. et al. Characterization of null and hypomorphic alleles of the Drosophila l(2)dtl/cdt2 gene: larval lethality and male fertility. Fly (Austin) 6, 173–183. https://doi.org/10.4161/fly.20247 (2012).

Qiao, L. et al. The E2F1/USP11 positive feedback loop promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis and inhibits autophagy by activating ERK/mTOR pathway. Cancer Lett. 514, 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.05.015 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. Bioinformatics-based discovery and characterization of an AKT-selective inhibitor 9-chloro-2-methylellipticinium acetate (CMEP) in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 252, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.035 (2007).

Xuan, X., Wang, Y., Sun, Y. & Huang, C. Identification of genes potentially associated with melanoma tumorigenesis through co-expression network analysis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 8495–8508. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S336295 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. DTL is a prognostic biomarker and promotes bladder Cancer progression through regulating the AKT/mTOR axis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022 (3369858). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3369858 (2022).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Targeting DTL induces cell cycle arrest and senescence and suppresses cell growth and colony formation through TPX2 inhibition in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Onco Targets Ther. 11, 1601–1616. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S147453 (2018).

Cui, H. et al. DTL promotes cancer progression by PDCD4 ubiquitin-dependent degradation. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, 350. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1358-x (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Overexpression of DTL enhances cell motility and promotes tumor metastasis in cervical adenocarcinoma by inducing RAC1-JNK-FOXO1 axis. Cell. Death Dis. 12, 929. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-04179-5 (2021).

Rooney, P. H. et al. Comparative genomic hybridization and chromosomal instability in solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 80, 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690433 (1999).

Higa, L. A. et al. L2DTL/CDT2 interacts with the CUL4/DDB1 complex and PCNA and regulates CDT1 proteolysis in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle 5, 1675–1680. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.5.15.3149 (2006).

Sansam, C. L. et al. DTL/CDT2 is essential for both CDT1 regulation and the early G2/M checkpoint. Genes Dev. 20, 3117–3129. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1482106 (2006).

Jin, J., Arias, E. E., Chen, J., Harper, J. W. & Walter, J. C. A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol. Cell 23, 709–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.010 (2006).

Abbas, T. et al. PCNA-dependent regulation of p21 ubiquitylation and degradation via the CRL4Cdt2 ubiquitin ligase complex. Genes Dev. 22, 2496–2506. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1676108 (2008).

Nishitani, H. et al. CDK inhibitor p21 is degraded by a proliferating cell nuclear antigen-coupled Cul4-DDB1Cdt2 pathway during S phase and after UV irradiation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29045–29052. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M806045200 (2008).

Kim, Y., Starostina, N. G. & Kipreos, E. T. The CRL4Cdt2 ubiquitin ligase targets the degradation of p21Cip1 to control replication licensing. Genes Dev. 22, 2507–2519. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1703708 (2008).

Bolanos-Garcia, V. M. & Blundell, T. L. BUB1 and BUBR1: multifaceted kinases of the cell cycle. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 141–150 (2011).

Yu, H. & Tang, Z. Bub1 multitasking in mitosis. Cell Cycle 4, 262–265 (2005).

Johnson, V. L., Scott, M. I., Holt, S. V., Hussein, D. & Taylor, S. S. Bub1 is required for kinetochore localization of BubR1, Cenp-E, Cenp-F and Mad2, and chromosome congression. J. Cell. Sci. 117, 1577–1589. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.01006 (2004).

Zhu, L. J., Pan, Y., Chen, X. Y. & Hou, P. F. BUB1 promotes proliferation of liver cancer cells by activating SMAD2 phosphorylation. Oncol. Lett. 19, 3506–3512. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2020.11445 (2020).

Han, J. Y., Han, Y. K., Park, G. Y., Kim, S. D. & Lee, C. G. Bub1 is required for maintaining cancer stem cells in breast cancer cell lines. Sci. Rep. 5, 15993. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15993 (2015).

Li, M. et al. BUB1 is identified as a potential therapeutic target for pancreatic Cancer treatment. Front. Public. Health 10, 900853. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.900853 (2022).

Fu, X. et al. Overexpression of BUB1B contributes to progression of prostate cancer and predicts poor outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 2211–2220. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S101994 (2016).

Grabsch, H. et al. Overexpression of the mitotic checkpoint genes BUB1, BUBR1, and BUB3 in gastric cancer–association with tumour cell proliferation. J. Pathol. 200, 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1324 (2003).

Sheldon, L. A. Inhibition of E2F1 activity and cell cycle progression by arsenic via retinoblastoma protein. Cell Cycle 16, 2058–2072. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2017.1338221 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Epigenetic factor EPC1 is a master regulator of DNA damage response by interacting with E2F1 to silence death and activate metastasis-related gene signatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv885 (2016).

Lai, Q. et al. E2F1 inhibits circulating cholesterol clearance by regulating Pcsk9 expression in the liver. JCI Insight 2. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.89729 (2017).

Alla, V. et al. E2F1 confers anticancer drug resistance by targeting ABC transporter family members and Bcl-2 via the p73/DNp73-miR-205 circuitry. Cell Cycle 11, 3067–3078. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.21476 (2012).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the General Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81972565) and Academy-level Science and Technology Plan of The First Affiliated Hospital of Shihezi University (QN202130).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiuyun Xuan: Methodology, Software, Project administration, Writing- original draft. Juanmei Cao: Methodology, Project administration, Writing- original draft. Li Chen: Methodology. Jing Zhang: Writing- reviewing and editing. Yue Qian: Writing- reviewing and editing. Changzheng Huang: Writing- reviewing and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of the Article contained an error in Figures 3, 6 and Supplementary File 6 in which the figures contain outdated data representations that do not reflect the final analysed results submitted for publication.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xuan, X., Cao, J., Chen, L. et al. DTL promotes the growth and migration of melanoma cells through the ERK/E2F1/BUB1 axis. Sci Rep 14, 26288 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76477-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76477-9