Abstract

Cell motility increases the fitness of bacterial cells. Previous research focused on the transcriptional regulator CdsR, which represses cellular autolysis and promotes spore formation in Bacillus thuringiensis. However, the targets of CdsR are mostly unknown. Here, we reported a new function of CdsR in regulating cell motility. Mutation of cdsR results in increase of cell mobility, and a number of related genes were upregulated compared to wild type HD73. Thus, we investigated the transcription of the fla/che gene cluster, which involves in cell mobility and comprises eight operons/genes, including motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, yaaR-fliG2, cheV-mogR, hag1, hag2, and yjbJ-flgG. Additionally, the motAB2 operon was discovered, which consists of homologs genes motA2 and motB2 that are like motA1 and motB1. Through promoter-lacZ fusion assays and EMSA experiments, it was discovered that CdsR directly regulates the motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, yaaR-fliG2, cheV-mogR, hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG, and motAB2 operons by binding to their promoter regions. Importantly, it was confirmed that CdsR is a metalloregulator and the binding to promoter can be inhibited by Cu (II) ions. This research enhances our understanding of the regulation of cell mobility in B. thuringiensis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The bacteria flagellum is a protein complex responsible for bacterial locomotion under various environmental conditions1. Bacterial cell motility is defined as the ability of bacteria to move in response to external stimuli, such as gradients of chemokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix components2. Cell chemotaxis, on the other hand, is the directed movement of bacteria towards or away from chemical substances in their environment. It is a type of motility that is driven by the sensing of chemical gradients. Bacterial cell chemotaxis is a tightly coordinated mechanism that enables cells to navigate and respond to their environment in a directed manner3. The relationship between cell motility and chemotaxis is crucial for bacterial survival. The bacteria flagellum acts as a propulsion system that allows bacteria to move towards favorable conditions while avoiding harmful environments. The ability is essential for bacterial survival and plays a significant role in various biological processes, including colonization, biofilm formation, and pathogenesis4.

There are several mechanisms by which the transcriptional regulation of bacterial motility and chemotaxis can occur. These mechanisms involve the control of gene expression through specific transcription factors, signaling pathways, and regulatory elements5,6,7,8. Specific examples, the Sigma factors initiate transcription of flagellar genes fla/che operon in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. The fla/che operon, which has a long 27 kb fla/che operon of 31 genes co-transcribed from the common Pfla/che promoter in B. subtilis8,9,10. DNA-binding proteins, such as the osmoregulation trans-factor OmpR, bind to specific sequences in the flhDC operon promoter and repress transcription in E. coli11. These regulatory mechanisms allow bacteria to respond to environmental cues and adapt their motility and chemotaxis behaviors accordingly.

The ArsR (Arsenical Resistance Operon Repressor) family transcriptional regulators are known for its role in conferring resistance to arsenic acid. This family of transcriptional regulators are found across various prokaryotes and play a crucial role in maintaining intracellular metal ion homeostasis12,13. The main function of these ArsR regulators is to act as metal-regulatory proteins that facilitate processes such as metal ion uptake, efflux, sequestration, and detoxification14. These actions are particularly important in preserving the equilibrium of metal ions within cells, especially when exposed to harsh environmental conditions. However, studies on the regulation of bacterial cell motility-related gene expression by ArsR family transcriptional regulators are rare.

B. thuringiensis is a gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium that produces parasporal crystals toxic to a wide range of insect larvae during sporulation15. Only a few transcriptional regulators of cell motility have been identified in B. thuringiensis. The MogR transcriptional regulator, encoded in the motility locus, was found to repress the expression of motility genes in B. thuringiensis 40716. PlcR is another important transcriptional regulator of virulence genes, which also affects cell motility16. Additionally, the SinI-SinR system, a regulatory system conserved between B. cereus and B. subtilis, consists of the transcriptional regulator SinR and its anti-repressor SinI. SinR acts as a master transcriptional repressor that controls the switch from a motile to a sessile lifestyle17,18. However, the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation for genes related to cell motility in B. thuringiensis are not well understood.

Results

Mutation of CdsR results in increased cell motility

Previous research has revealed that the cdsR gene in Bacillus thuringiensis HD73 (locus tag HD73_RS03760), which encodes a novel ArsR family transcriptional regulator, is involved in spore formation and cellular autolysis19. To identify putative target genes/operons that are regulated by CdsR, we analyzed the RNA-seq data at T0 and found that the expression of genes related to cell motility and chemotaxis were up-regulated in the cdsR mutant compared to the wild type HD73 (Table 1). To validate these findings from the RNA-seq data, we randomly selected five genes for RT-qPCR analysis. The results showed that the transcription levels of cheV, fliM, motA2, cheR, and fliG1 genes were higher in the cdsR mutant than that in HD73 (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the motility and chemotaxis-related genes were up-regulated in the cdsR mutant.

Comparison of cell motility of the B. thuringiensis HD73 and ΔcdsR. (A) Analysis of cheV, fliM, motA2, cheR, and fliG1 expression in ΔcdsR and HD73 strains at T0 by RT-qPCR. Experiments were conducted in triplicate. Error bars represent standard deviations, and data were analyzed using a t-test (*, P < 0.05. **, P < 0.01. ***, P < 0.001.). (B) Cell motility of the ΔcdsR (mutant strain) and CcdsR (complementary strain) were compared with that of the HD73 (wild-type strain). The cell motility of B. thuringiensis strains was observed in LB solid medium containing 0.5% agar. (C) Comparison of plaque diameters of the ΔcdsR, CcdsR, and HD73. Five independent experiments were used to analyze the data by t-test (****, P < 0.0001).

To further investigate the impact of cdsR deletion on cell motility in B. thuringiensis HD73 strains, we conducted a swarming assay. The results showed a significant increase in plaque diameter in ΔcdsR (cdsR deletion mutant) and a significant decrease in CcdsR (complementation strain) compared to HD73 (Fig. 1B). Specifically, the plaque diameter was approximately 3.94 ± 0.39 cm for HD73, whereas the ΔcdsR and CcdsR displayed a diameter of approximately 8.31 ± 0.43 cm and 1.85 ± 0.14 cm, respectively (Fig. 1C). These findings provide evidence that deletion of the cdsR gene leads to a notable increase in cell motility.

Prediction of che/fla cluster in B. thuringiensis HD73

The che/fla gene cluster includes the che gene cluster (encapsulating key genes in the chemotaxis pathway) and the fla gene cluster (encapsulating key genes in flagellar assembly). Operons in the che/fla gene cluster were predicted based on RNA-seq data (accession no. GSE216307) and Rockhopper software20 (version 2.03), a comprehensive system that supports the various stages of RNA-seq date analysis, including normalizing data from different experiments, quantifying transcript abundance, and testing for differential transcript expression. The che gene cluster consists of four operons (motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, and cheV-mogR) (Table 1; Fig. 2A). The fla cluster consists of four genes/operons (yaaR-fliG2, hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG) (Table 1; Fig. 2A). Moreover, motA and motB genes were responsible for the production of proteins that were involved in bacterial flagellar motility. The motAB1 operon consists of two genes, motA1 and motB1, which also have homologs in the HD73 genome, motA2 and motB2, respectively (Table 1; Fig. 2A). The cheY-yrhK operon consist of five genes (cheY, cheA, cheC, ygaD, and yrhK). The lamB-cheR operon consist of two genes, including lamB and cheR. The cheV-mogR operon consists of two genes, including cheV and mogR. The yaaR-fliG2 operon consist of twenty genes (yaaR, flgN, flgK, flgL, fliD, fliS, yopR, flgB, flgC, fliE, fliF, fliG1, fliH, fliI, phoU, fliK, flgD, flgE, ykuH, and fliG2). The hag1 and hag2 were homologous genes of hag gene and each was transcribed independently. Finally, the yjbJ-flgG operon consist of twelve genes (yjbJ, fliN1, fliM, fliN2, fliN3, fliP, fliQ, fliR, flhB, flhA, flhF, and flgG) (Table 1; Fig. 2A).

Transcription of hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG, and yaaR-fliG2 operons/genes are regulated by CdsR. (A) RNA-seq data were analysed using Rockhopper software (version 2.03) and operons in the che/fla gene cluster were predicted in B. thuringiensis. Genes of the same color in the figure belong to a single operon. Open reading frames (ORFs) are represented by broad arrows, and promoter regions are represented by black arrows. The different operons in the figure are described in Table 1. The genetic organization of the fla gene cluster, including the yaaR-fliG2, hag1, hag2, and yjbJ-flgG operons, are represented by green, dark red, light red, and blue arrows, respectively. The numbers at the ends of the lines represent the locations in the genome. (B) Schematic representation of the B. thuringiensis flagellum. The flagellum is divided into three structural parts: the helical filament, which acts as a propeller; the basal body, which is embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane; and the hook, which connects the filament to the basal body. The basal body acts as a bidirectional rotary motor consisting of a rotor ring complex and several stator units around the rotor. (C) β-galactosidase activity of Phag1-lacZ in the cdsR mutant strains and HD73 wild-type strain. T0 is the end of exponential phase, and Tn is n hours after T0. Each value represents the mean of at least three replicates. (D) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to hag1 gene promoter fragment (317 bp). The last lane, incubation of 200-fold greater unlabeled Phag1 probe mixed with the labeled Phag1 probe and 1.79 µM CdsR. (E) β-galactosidase activity of Phag2-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (F) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to hag2 gene promoter fragment (610 bp). (G) β-galactosidase activity of PyjbJ-flgG-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (H) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to yjbJ-flgG operon promoter fragment (316 bp). (I) β-galactosidase activity of PyaaR-fliG2-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (J) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to yaaR-fliG2 operon promoter fragment (235 bp).

CdsR negatively regulates the expression of fla gene cluster

The bacteria flagellum is a rotary nanomachine comprised of more than 25 genes that encode various proteins. It comprises three main structural parts: the long helical filament, which acts as a propeller to produce thrust; the basal body, which is a membrane-embedded rotary motor; and the hook, which acts as a universal joint connecting the filament to the basal body21. In B. thuringiensis, a fla/che gene cluster of 45 genes with homology to flagellar-based motility genes is present (Fig. 2B). We studied the transcription and regulation of four operons/genes, which belongs to the fla gene cluster, including Phag1, Phag2, PyaaR-fliG2 and PyjbJ-flgG, respectively (Fig. 2A). The Phag1-lacZ, Phag2-lacZ, PyaaR-fliG2-lacZ and PyjbJ-flgG-lacZ fusions were constructed and transformed into HD73 and ΔcdsR mutant. The β-galactosidase assay showed that the promoter of Phag1 had almost no transcriptional activity from T−1 to T6 both in HD73 and ΔcdsR (Fig. 2C). Compared with HD73, the transcriptional activity of the Phag2 increased slightly from T1 to T6 in ΔcdsR, with no significant difference from T−1 to T0 (Fig. 2E). To determine whether CdsR directly or indirectly regulates the Phag1 and Phag2, we tested the binding of the CdsR protein to the hag1 and hag2 promoter regions in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). EMSA result showed that 0.48 nM FAM probe-labeled Phag1 could bind to CdsR at concentrations of 0.89 µM, 1.34 µM, and 1.79 µM, respectively (Fig. 2D). Notably, a 200-fold excess of unlabeled Phag1 competed with the labeled Phag1, confirming the specific binding (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, when 0.88 nM labeled Phag2 was exposed to CdsR with concentrations ranging from 0.45 µM to 1.34 µM, the band shift could be detected, indicating that CdsR can bind to the hag2 promoter region (Fig. 2F). These results strongly supported the theory that CdsR directly regulates the expression of hag1 and hag2.

To validate the transcription of the yaaR-fliG2 and yjbJ-flgG in HD73 and ΔcdsR, PyaaR-fliG2 and PyjbJ-flgG promoter fusion with lacZ gene were constructed and analyzed by evaluating β-galactosidase activity. The result showed that the transcriptional activity of PyjbJ-flgG was increased in ΔcdsR compared to that in HD73 (Fig. 2G). EMSA result showed that the probe-labeled PyjbJ-fliG2 at 0.96 nM binds to CdsR (concentrations from 0.92 µM to 3.66 µM), and competitively inhibited by 200-fold unlabeled promoter, confirming specific binding (Fig. 2H). The result suggests that CdsR directly binds to the yjbJ-flgG promoter region. In addition, the β-galactosidase activity showed that the PyaaR-fliG2 promoter transcriptional activity increased from T−1 to T6 in ΔcdsR compared to HD73 (Fig. 2I), and EMSA confirmed that CdsR directly binds to the PyaaR-fliG2 promoter (Fig. 2J). These results collectively suggest that CdsR negatively regulates the expression of hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG, and yaaR-fliG2 operons/genes.

CdsR negatively regulates the expression of che gene cluster

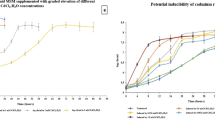

We then studied the transcription and regulation of che gene cluster, including cheY-yrhK, lamb-cheR, and cheV-mogR, respectively (Fig. 3A). The signaling core of the chemotaxis pathway consists of chemoreceptors (MCPs), a histidine kinase CheA, and a methylated receptor CheR that controls the autophosphorylation activity of CheA22. CheA then transfers the phosphoryl group to the CheY, a response regulator. CheV is a scaffold protein that interacts with both CheA and CheY, regulating their activity. The phosphorylated form of CheY (CheY-P) induces clockwise rotation of the flagellar motor, promoting transient tumbles that reorient the cell body (Fig. 3B). To detect the transcription dynamics of these operons, the cheY-yrhK (PcheY-yrhK), lamB-cheR (PlamB-cheR), and cheV-mogR (PcheV-mogR) promoters were fused to lacZ reporter gene. We identified the expression of these three operons in both HD73 and ΔcdsR through β-galactosidase assay. The result showed that the activities of the PcheY-yrhK and PcheV-mogR were significantly higher in ΔcdsR than in HD73 from T−1 to T6 (Fig. 3C and D). PlamB-cheR activity was similar in ΔcdsR and HD73 from T−1 to T3, but higher in ΔcdsR from T4 to T6 (Fig. 3E). These results clearly indicate that CdsR represses the transcription of cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, and cheV-mogR.

Transcription of cheY-yrhK, lamb-cheR, and cheV-mogR operons/genes are regulated by CdsR. (A) Genetic organization of the che gene cluster. ORFs are represented by different color arrows, and promoter regions are represented by black arrows. Blue, orange, and light-yellow arrows indicate cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, and cheV-mogR operon, respectively. The numbers at the ends of the lines represent the locations in the genome for the two end bases. (B) Chemotaxis signaling pathway of B. thuringiensis. The P represents the phosphate group in the figure. (C) β-galactosidase activity of PcheY-yrhK-lacZ in the cdsR mutant strains and HD73 wild-type strain. Each value represents the mean of at least three replicates. (D) β-galactosidase activity of PcheV-mogR-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (E) β-galactosidase activity of PlamB-cheR-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (F) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to cheY-yrhK operon promoter fragment (260 bp). The last lane, incubation of 200-fold greater unlabeled PcheY-yrhK probe mixed with the labeled PcheY-yrhK probe and 2.13 µM CdsR. (G) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to cheV-mogR operon promoter fragment (203 bp). (H) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to lamB-cheR operon promoter fragment (239 bp).

To determine whether CdsR binds to the promoter regions of cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, and cheV-mogR, EMSA was performed. Various concentrations of the CdsR protein were used to bind to the 1.18 nM probe-labeled PcheY-yrhK. The result showed that high concentration (1.60 µM and 2.13 µM) of CdsR can bind to the labeled PcheY-yrhK, and this binding is competed by 200-fold excess of unlabeled promoter (Fig. 3F). Similarly, FAM-labeled cheV-mogR promoter fragments were incubated with different amounts of CdsR and assayed for the formation of Protein-DNA complexes. Slower-migrating probe-protein complexes were observed upon incubation with increasing amounts of CdsR (Fig. 3G). CdsR protein with a concentration of 3.20 µM and 4.26 µM could also bind to probe-labeled PlamB-cheR, and competitively inhibited by 200-fold unlabeled promoter, confirming specific binding (Fig. 3H). These results collectively suggest that CdsR negatively regulates the expression of cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, and cheV-mogR.

Transcriptional activity of MotAB flagellar motor genes

To confirm whether CdsR regulates the motAB1 and motAB2 operons, β-galactosidase activities were performed in HD73 and ΔcdsR, respectively. The β-galactosidase assay showed that in HD73, the activity of the PmotAB1 remained low from T−1 to T6. However, in ΔcdsR, the transcriptional activity of the PmotAB1 was significantly higher than in HD73 from T−1 to T6 and increased significantly from T0 to T6 (Fig. 4A). The result suggests that motAB1 expression is suppressed by CdsR. To confirm whether the CdsR protein could bind to motAB1 promoter region, we conducted an EMSA which showed that high concentration (1.71 µM) of CdsR is able to bind to 1.18 nM of probe-labeled PmotAB1. Notably, 200-fold excess of unlabeled PmotAB1 could compete with the labeled promoter, confirming a specific binding (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that motAB1 operon is negatively regulated by CdsR.

Transcription ofmotAB1 andmotAB2 operons depended on CdsR. (A) β-galactosidase activity of PmotAB1-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73 in SSM medium at T-1 to T6. (B) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to motAB1 gene promoter fragment (260 bp). The last lane, incubation of 200-fold greater unlabeled PmotAB1 probe mixed with the labeled PmotAB1 probe and 1.71 µM CdsR. (C) β-galactosidase activity of PmotAB2-lacZ in ΔcdsR and HD73. (D) EMSA experiment confirms CdsR binding to motAB2 promoter gene region (269 bp).

Furthermore, to investigate whether motAB2, a redundant operon of motAB1, is also regulated by CdsR, β-galactosidase assay and EMSA were performed. The motAB2 operon promoter was fused with the lacZ reporter gene and transformed into HD73 and ΔcdsR. β-galactosidase assay was measured, which showed that the activity of PmotAB2 increased from T−1 to T6 and reached the highest level at T6 in ΔcdsR. However, the transcriptional activity of PmotAB2 was inhibited from T−1 to T6 in HD73 (Fig. 4C). Then, we tested the binding of the CdsR protein to the motAB1 operon promoter region. EMSA result showed that various concentrations of the CdsR protein were used to binding 1.14 nM of the PmotAB2-labeled probe. At a concentration of 1.28 µM, the CdsR protein was unable to effectively bind to the PmotAB2-labeled probe. However, at a higher concentration (3.83 µM), CdsR was able to completely shift the probe-labeled PmotAB2. Notably, a 200-fold excess of unlabeled PmotAB2 competed with the labeled PmotAB, confirming the specific binding (Fig. 4D). These results collectively indicate that motAB2 operon is negatively regulated by CdsR.

CdsR is a metalloregulatory protein

ArsR family transcription factor is a winged-helix-turn-helix transcriptional regulator that may function as a metal-sensing protein, modulating the expression of genes associated with metal homeostasis14. CdsR consists of 95 amino acids and belongs to the ArsR family of transcriptional regulators, which include a single helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain ranging from 15 to 90 amino acid residues19. To identify which metal ions, regulate CdsR activity, we next examined the effect of metal ions on the binding of CdsR protein to the cheV-mogR operon promoter. EMSA experiment was conducted under metal ions condition (Fig. 5A, lanes 1–3). When Cu (II) was co-incubated with the probe-labeled probe promoter fragment and 1.22 µM CdsR, the protein-DNA complex formation was disrupted (Fig. 5A, lane 4). However, this phenomenon was not observed with the addition of Ca (II), Mg (II), Cd (II), Ni (II), Mn (II), and Zn (II) (Fig. 5A, lanes 5–10). The results suggest that Cu (II) specifically impairs the DNA-binding ability of CdsR, indicating that CdsR may be a Cu (II)-binding protein.

The metal Cu (II) ions inhibit CdsR binding to promoters. (A) EMSA experiment confirms that the binding of CdsR to PcheV-mogR is specifically inhibited by Cu (II) ions. The probe-labeled cheV-mogR operon promoter was incubated with different kinds of metal ions (0.5 mM) with 1.22 µM concentrations of CdsR protein or without CdsR protein. (B) EMSA experiment confirms that the binding of CdsR to PlrgAB is specifically inhibited by Cu (II) ions. The probe-labeled lrgAB operon promoter was incubated with different kinds of metal ions (1 mM) with 9.67 µM concentrations of CdsR protein or without CdsR protein.

Additionally, previous studies have shown that CdsR has a negative regulatory effect on the lrgAB gene, which encodes holin-like protein19. To confirm whether the addition of Cu (II) disrupts the binding of CdsR to the lrgAB promoter, we conducted EMSA experiments to reconfirm that the CdsR protein responds to Cu (II). EMSA was performed with the CdsR protein directly binding to the PlrgAB promoter as a positive control (Fig. 5B, lanes 1–3). When Cu (II) was co-incubated with the labelled PlrgAB promoter fragment and 9.67 µM concentrations of CdsR, CdsR protein-PlrgAB promoter complex formation was disrupted (Fig. 5B, lane 4). However, no disruption of protein-DNA complex formation was observed when adding Ca (II), Mg (II), Cd (II), Ni (II), Mn (II), and Zn (II) (Fig. 5B, lanes 5–10). This result again suggests that Cu (II) specifically inhibits the function of CdsR. In turn, CdsR may regulate the expression of certain genes and maintain homeostasis by responding to the intracellular concentration of Cu (II) ions.

To further investigate the effect of the presence and absence of Cu(II) on cell motility in B. thuringiensis HD73 strains, we also conducted a swarming assay. The results showed that the plaque diameter of HD73 strain with Cu(II) was significantly increased in the presence of Cu(II) compared to the absence of Cu(II) (Fig. 6A). Specifically, the plaque diameter of HD73 in the absence of Cu(II) was approximately 3.50 ± 0.26 cm, whereas the plaque diameter of HD73 in the presence of Cu(II) was approximately 5.57 ± 0.15 cm (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that the presence of Cu(II) significantly increases the cell motility of the HD73 wild strain.

Comparison of cell motility of HD73 strains in the presence and absence of Cu(II). (A) The cell motility of HD73 strain was compared in the presence and absence of Cu(II). The cell motility of B. thuringiensis strains was observed in LB solid medium containing 0.5% agar. (B) Comparison of plaque diameters of the HD73 strain in the presence and absence of Cu(II). Five independent experiments were used to analyze the data by t-test (****, P < 0.0001).

Discussion

B. subtilis is a Gram-positive bacterium that possesses multiple flagella on its cell surface, like E. coli and Salmonella. However, the structure and function of the flagella in B. subtilis differ from those in E. coli and Salmonella21. For example, thirty-two genes required for basal body synthesis are concentrated in the large 27 kb fla/che operon, which is expressed by RNA polymerase and the vegetative sigma factor σA. Once hook assembly is complete, the alternative sigma factor σD is activated to express a set of genes dedicated to filament assembly and rotation5. In contrast, the B. thuringiensis fla/che gene cluster on cell motility consists of 45 genes (Fig. 2A), and no orthologs of σD have been identified in the B. thuringiensis genome. In this study, we identified for the first time that the ArsR family transcriptional regulator CdsR directly regulates the fla/che gene cluster expression in B. thuringiensis. More importantly, we predicted eight operons in the fla/che gene cluster (Fig. 2A), and there may be other operons that we will follow up with RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription PCR) for detailed and accurate validation.

Previous studies have found that CdsR is highly conserved in the B. cereus group19. Therefore, it is possible that the ArsR family transcriptional regulator CdsR directly regulates expression of the fla/che gene cluster in the B. cereus group. At least seven species make up the group, including B. cereus, B. anthracis, B. thuringiensis, B. weihenstephanensis, B. mycoides, B. pseudomycoides, and B. cytotoxicus. These species can be found in various environments, such as soil, air, and water23. Most strains of B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, B. weihenstephanensis, and B. cytotoxicus are motile due to peritrichous flagella, while B. anthracis, B. mycoides, and B. pseudomycoides are non-motile23,24,25. Since CdsR is highly conserved among the four strains in B. cereus (100% amino acid similarity), B. thuringiensis (100%), and B. cytotoxicus (95%). It is hypothesized that CdsR may regulate cell motility. The study of the regulatory mechanisms of cell motility in all other bacteria of the B. cereus group will be instructive.

The ArsR family transcriptional regulator is widely distributed among microorganisms and is involved in diverse cellular events26,27. Its primary function is to act as a metal sensor, helping to maintain intracellular homeostasis12,28. The role of ArsR family transcriptional regulator is to repress the genes or operons expression when related to stress-inducing concentrations of various heavy metal ions27. Several studies have shown that the presence of metal ions inhibits DNA-binding activity of ArsR family members, such as ArsR-SmtB, MerR, CsoR-RcnR, CopY, DtxR, Fur, NikR, CmtR, and NmtR transcriptional regulators13,26. In Brucella, ArsR6 autoregulates its own expression to maintain bacterial intracellular Cu (II) and Ni (II) homeostasis, which favors bacterial survival in hostile environments29. In this study, we found for the first time that the transcriptional regulator CdsR can respond to Cu (II) in vitro (Fig. 5). Subsequently, we will focus on the key sites in the CdsR amino acid sequence that bind Cu (II) and how CdsR senses changes in the concentration of intracellular Cu (II) to precisely regulate target genes. Despite the presence of Cu (II) disrupts the binding of CdsR to target genes, however, we did not address in vitro experiments of CdsR binding to Cu (II). Additionally, it is unclear whether CdsR binds Cu inside the cell and how it senses changes in the concentration of Cu inside the bacteria cell. These questions will be addressed in subsequent studies.

The fla/che gene cluster has eight operons/genes, including motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamb-cheR, yaaR-fliG2, cheV-mogR, hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG. In addition, a motAB2 operon were investigated. The expression of motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamb-cheR, yaaR-fliG2, cheV-mogR, hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG and motAB2, which are controlled by CdsR, are negatively regulated. Furthermore, when higher concentrations of Cu (II) are present in B. thuringiensis cell, CdsR may bind Cu (II), which in turn prevents CdsR from binding to the PmotAB1, PcheY-yrhK, Plamb-cheR, PyaaR-fliG2, PcheV-mogR, Phag1, Phag2, PyjbJ-flgG and PmotAB2 promoter regions (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). In conclusion, the fla/che gene cluster has different expression and regulation in different bacteria. The data presented in this study may deepen our understanding of the transcriptional mode of the fla/che gene cluster, and thus help us to better understand the regulation mechanism of bacterial motility-associated gene cluster.

A previous study showed that CdsR is a negatively autoregulated transcriptional regulator. CdsR consists of 95 amino acids and belongs to the ArsR family of transcriptional regulators, which include a single helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain ranging from 15 to 90 amino acid residues. Furthermore, the genes upstream and downstream of cdsR include istA, sspH, and dtpA, which encode the IS21-like element IS232 family transposase, acid-soluble spore protein H, and peptide MFS transporter, respectively19. To obtain a deeper understanding of the regulator motifs of the ArsR family transcriptional regulator CdsR, we analyzed a conserved sequence of target genes/operons (such as hag1, hag2, yjbJ-flgG, yaaR-fliG2, cheY-yrhK, cheV-mogR, lamb-cheR, motAB1, motAB2, lrgAB, cdsR, and cwlD) directly regulated by CdsR using the MEME website (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme). The results showed that the alignment of the 12 promoter regions confirmed the presence of a CdsR binding site rich in G bases. The 12 promoters’ sequences were aligned and the conserved sequence WGAGGKGGYTC was identified for CdsR regulated genes (Table S3 and Fig. 7). In a follow-up study, we are going to confirm whether the CdsR binding site in the promoter regions of the 12 target genes is this predicted site by a DNase I footprinting protection assay.

Characterization of a CdsR conserved DNA sequence. The motif of the CdsR-binding DNA was predicted by MEME. The colored region corresponds to a 11-bp DNA sequence highly conserved in the 12 promoter regions. The height of each column indicates the sequence conservation at that position, while the height of symbols within the stack indicates the relative frequency of each nucleic acid at that position. Motif consensus of CdsR binding promoter regions is presented. W is A or T; K is G or T; Y is C or T.

In this study, we focused on the transcriptional regulation of the fla/che gene cluster, which is involved in cell motility and chemotaxis in B. thuringiensis HD73. The RNA-seq data of the cdsR deletion mutant was investigated, and it was found that the expression of genes associated with cell motility were all up-regulated in the cdsR deletion mutant compared to the HD73 wild-type. Additionally, deletion of cdsR resulted in enhanced cell motility. Subsequently, motAB1, cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, cheV-mogR, yaaR-fliG2, hag1, hag2, and yjbJ-flgG operons/genes were found at the fla/che gene cluster in B. thuringiensis HD73. The results of the β-galactosidase activity and Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) suggest that CdsR regulates the expression of motAB1, motAB2, cheY-yrhK, lamB-cheR, cheV-mogR, yaaR-fliG2, hag1, hag2, and yjbJ-flgG. Furthermore, we found that the ArsR family transcriptional regulator CdsR is inhibited by metallic Cu (II) ions. This work provides new insights into the regulation of cell motility in B. thuringiensis.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD73 (hereafter designated as HD73, reference genome sequence: NC_020238.1) and derivatives were grown at 30 °C in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% NaCl) or on solid LB medium supplemented with 1.5% agar. Schaeffer’s sporulation medium30 (SSM; 0.8% nutrient broth, 0.012% MgSO4, 0.1% KCl, 0.5 mM NaOH, 1 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.01 µM MnCl2, and 1 µM FeSO4) was used to observe the development of bacterial cells. Escherichia coli TG1 was used for molecular cloning experiments, and E. coli ET was used for producing non-methylated plasmid DNA for B. thuringiensis transformations31,32; both strains were grown at 37 °C in LB medium. The antibiotics were added at the following concentrations for the growth of B. thuringiensis: 5 µg/ml erythromycin and 50 µg/ml kanamycin. For the growth of E. coli, 100 µg/ml of ampicillin was added when needed. The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

DNA manipulation and transformation

Plasmid DNA was extracted from E. coli cells with a Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Axygen, Beijing, China). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase (Takara Biotechnology Corporation, Dalian, China) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed with the high-fidelity PrimeStar HS DNA polymerase (Takara Biotechnology Corporation, Beijing, China) or Taq DNA polymerase (BioMed, Beijing, China). DNA fragments were purified from 1% agarose gels, using the AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, Beijing, China). Standard transformation procedures for E. coli33, and B. thuringiensis34 were described previously.

Reverse transcription (RT)-qPCR assay

The total RNA was extracted from HD73 and ∆cdsR cells collected at T0 (T0 indicates the end of the exponential growth phase) using the RNAprep Pure Kit (Aidlab, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was then subjected to reverse transcription using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) to synthesize cDNA. The cDNA samples were diluted to a concentration of 200 ng/µL for subsequent analysis. The transcriptional levels of the target genes were determined by conducting RT-qPCR using the ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR master mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The 16 S rRNA gene was utilized as an internal control to normalize the expression of the target genes. The specific primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials. Finally, the RT-qPCR data analysis was performed using the 2 − ΔΔCt method. Subsequently, the data are expressed as the mean fold change relative to the control samples, which were used to assess the relative expression levels of the target genes in HD73 and ∆cdsR cells. Significant differences were determined by Student’s t-test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001). Statistical analysis was performed on GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Swarming assay

HD73 and ∆cdsR strains were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 1.0. For the swarming assay, 1 µL of culture was spotted onto a LB (0.5% agar) and incubated at 30 °C for 12 h. Photographs were obtained using the ImageScanner III (Cytiva, Stockholm, Sweden).

β-galactosidase activity assays

The motAB1 (PmotAB1, 260 bp) and motAB2 (PmotAB2, 269 bp) gene promoters were amplified from HD73 genomic DNA using the primers PmotAB1-F/PmotAB1-R and PmotAB2-F/PmotAB2-R, respectively. The primers used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the Supplementary Materials. The PmotAB1 and PmotAB2 were digested with PstI and BamHI, followed by ligation into the linearized pHT304-18Z plasmid, which harbors a promoter-less lacZ35, to obtain the recombinant plasmids 304PmotAB1 and 304PmotAB2. The 304PmotAB1 and 304PmotAB2 plasmid were introduced into HD73 and ∆cdsR, resulting in HD(PmotAB1), ∆cdsR(PmotAB1), HD(PmotAB2) and ∆cdsR(PmotAB2), respectively. The HD(PmotAB1), ∆cdsR(PmotAB1), HD(PmotAB2) and ∆cdsR(PmotAB2) strains were validated by PCR.

The promoters’ sequence of the cheY-yrhK operon (260 bp upstream of the cheY-yrhK translational start codon), lamB-cheR operon (239 bp), yaaR-fliG2 operon (235 bp), cheV-mogR operon (203 bp), hag1 gene (317 bp), hag2 gene (610 bp), and yjbJ-flgG operon (316 bp) were amplified from HD73 genomic DNA with the primers PcheY-yrhK-F/PcheY-yrhK-R, PlamB-cheR-F/PlamB-cheR-R, PyaaR-fliG2-F/PyaaR-fliG2-R, PcheV-mogR-F/PcheV-mogR-R, Phag1-F/Phag1-R, Phag2-F/Phag2-R, PyjbJ-flgG-F/PyjbJ-flgG-R, respectively. These fragments of the promoter regions were digested with PstI and BamHI, followed by ligation into the linearized pHT304-18Z plasmid35. The recombinant 304PcheY-yrhK, 304PlamB-cheR, 304PyaaR-fliG2, 304PcheV-mogR, 304Phag1, 304Phag2, and 304PyjbJ-flgG plasmids were introduced into HD73 and ∆cdsR, resulting in HD(PcheY-yrhK), ∆cdsR(PcheY-yrhK), HD(PlamB-cheR), ∆cdsR(PlamB-cheR), HD(PyaaR-fliG2), ∆cdsR(PyaaR-fliG2), HD(PcheV-mogR), ∆cdsR(PcheV-mogR), HD(Phag1), ∆cdsR(Phag1), HD(Phag2), ∆cdsR(Phag2), HD(PyjbJ-flgG), and ∆cdsR(PyjbJ-flgG), respectively. These generated strains were validated by erythromycin resistance and PCR identification.

The β-galactosidase activities were measured as follows: the samples were collected from T−1 to T6 (T0 indicates the end of the exponential growth phase, and Tn indicates the number of hours before (-) or after T0) at 1 h intervals. For each sample, 2 mL cultures from 100 mL were centrifuged (12,000×g, 1 min), and the pellets were stored at −40 °C before the test. For the determination of β-galactosidase activities, samples were resuspended in 0.5 mL of Z-buffer (0.06 M Na2HPO4, 0.04 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M KCL, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol). The cells were disrupted with glass beads (0.1 mm; BioSpec; America) in a Mini Beadbeater-96 (BioSpec; America), and cell extract was obtained after centrifugation. Next, 0.7 mL of Z-buffer and 0.2 mL of 4 mg mL−1 2-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (sigma) for β-galactosidase assay were added to 100 µL of cell extract. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.5 mL of 1 M Na2CO3. Subsequently, the optical density of the reaction mixture was measured at 420 nm for the β-galactosidase assay. The protein content was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Specific activities are expressed in units of β-galactosidase per milligram of protein (Miller units). Miller units were calculated using the following formula: units = (OD420 × 1500)/T × V × protein concentration. T is the reaction time (min) and V is the volume of sample added (µL). Values are reported as the mean and standard error of at least 3 independent assays.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

The expression and purification of CdsR-His protein were performed as previously described19. The promoter DNA fragment was PCR amplified from HD73 genomic DNA using specific primers labeled with a 5′-end FAM modification and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Electrophoresis mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed to analyze the binding between CdsR protein and PmotAB1, PmotAB2, PcheY-yrhK, PlamB-cheR, PyaaR-fliG2, PcheV-mogR, Phag1, Phag2, PyjbJ-flgG, and PlrgAB promoter fragments. Briefly, the promoter DNA probe was incubated with different concentrations of purified CdsR at 25 °C for 30 min in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 50mM Nacl, 500 ng poly (dI: dC), pH 7.5 and 4% (v/v) glycerol) in a total volume of 20 µL. The DNA-protein mixtures were applied to non-denaturing 6.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels in TBE buffer (90 mM Tris-base, 90 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) for resolution of the complexes, using a Mini-PROTEAN system (Bio-Rad) at 170 V for 1 h. Signals were visualized directly from the gel with the FLA Imager FLA-5100 (Fujifilm).

Transcriptome sequencing analysis

The HD73 and ΔcdsR mutant strains were cultured in SSM at 30 °C and harvested at T0. Total RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Bacteria Kit (aidlab, Beijing, China) to RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). The relative transcript abundance was calculated as fragments per kilobase of exon sequence per million mapped sequence reads (FPKM). Genes were considered differentially expressed only if they met the criteria of having an adjusted P-value ≤ 0.05 and absolute value of log2fold-change ≥ 1. The differentially expressed genes were subjected to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis using an online gene function analysis tool. All RNA-Seq data were uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (accession no. GSE216307).

Data availability

Data are contained within the article. We have uploaded the RNA-seq data, which will be available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database with the accession no. GSE216307.

References

Minamino, T., Kinoshita, M. & Structure Assembly, and function of Flagella responsible for bacterial locomotion. EcoSal Plus 11, eesp00112023. https://doi.org/10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0011-2023 (2023).

Tanimura, S. et al. ERK signaling promotes cell motility by inducing the localization of myosin 1E to lamellipodial tips. J. Cell. Biol. 214, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201503123 (2016).

Huang, Z., Pan, X., Xu, N. & Guo, M. Bacterial chemotaxis coupling protein: structure, function and diversity. Microbiol. Res. 219, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2018.11.001 (2019).

Chaban, B., Hughes, H. V. & Beeby, M. The flagellum in bacterial pathogens: for motility and a whole lot more. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 46, 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.10.032 (2015).

Mukherjee, S. & Kearns, D. B. The structure and regulation of flagella in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 48, 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092406 (2014).

Davis, M. C., Kesthely, C. A., Franklin, E. A. & MacLellan, S. R. The essential activities of the bacterial sigma factor. Can. J. Microbiol. 63, 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjm-2016-0576 (2017).

Chilcott, G. S. & Hughes, K. T. Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biology Reviews: MMBR. 64, 694–708. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.64.4.694-708.2000 (2000).

Cozy, L. M. et al. SlrA/SinR/SlrR inhibits motility gene expression upstream of a hypersensitive and hysteretic switch at the level of σ(D) in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 83, 1210–1228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08003.x (2012).

Studholme, D. J. & Buck, M. The alternative sigma factor sigma(28) of the extreme thermophile Aquifex aeolicus restores motility to an Escherichia coli fliA mutant. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191, 103–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09325.x (2000).

Cozy, L. M. & Kearns, D. B. Gene position in a long operon governs motility development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07112.x (2010).

Shin, S. & Park, C. Modulation of flagellar expression in Escherichia coli by acetyl phosphate and the osmoregulator OmpR. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4696–4702. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.177.16.4696-4702.1995 (1995).

Busenlehner, L. S., Pennella, M. A. & Giedroc, D. P. The SmtB/ArsR family of metalloregulatory transcriptional repressors: structural insights into prokaryotic metal resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-6445(03)00054-8 (2003).

Cavet, J. S., Graham, A. I., Meng, W. & Robinson, N. J. A cadmium-lead-sensing ArsR-SmtB repressor with novel sensory sites. Complementary metal discrimination by NmtR AND CmtR in a common cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 44560–44566. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M307877200 (2003).

Ren, S., Li, Q., Xie, L. & Xie, J. Molecular mechanisms underlying the function diversity of ArsR Family Metalloregulator. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 27, 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevEukaryotGeneExpr.2016018476 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. A strong promoter of a non-cry gene directs expression of the cry1Ac gene in Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 3687–3699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-8836-5 (2018).

Gohar, M. et al. Two-dimensional electrophoresis analysis of the extracellular proteome of Bacillus cereus reveals the importance of the PlcR regulon. Proteomics. 2, 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/1615-9861(200206)2:6%3C;784::AID-PROT784%3E;3.0.CO;2-R (2002).

Fagerlund, A. et al. SinR controls enterotoxin expression in Bacillus thuringiensis biofilms. PloS One. 9, e87532. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087532 (2014).

Kearns, D. B., Chu, F., Branda, S. S., Kolter, R. & Losick, R. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 739–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04440.x (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Cell death dependent on holins LrgAB repressed by a novel ArsR family regulator CdsR. Cell. Death Discovery. 10, 173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-024-01942-3 (2024).

Tjaden, B. De novo assembly of bacterial transcriptomes from RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 16, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0572-2 (2015).

Terahara, N., Namba, K. & Minamino, T. Dynamic exchange of two types of stator units in Bacillus subtilis flagellar motor in response to environmental changes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 2897–2907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.009 (2020).

Bi, S. & Sourjik, V. Stimulus sensing and signal processing in bacterial chemotaxis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 45, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2018.02.002 (2018).

Smith, V. et al. MogR is a ubiquitous transcriptional repressor affecting motility, Biofilm formation and virulence in Bacillus thuringiensis. Front. Microbiol. 11, 610650. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.610650 (2020).

Twine, S. M. et al. Motility and flagellar glycosylation in Clostridium difficile. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7050–7062. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00861-09 (2009).

Guinebretière, M. H. et al. Bacillus cytotoxicus sp. nov. is a novel thermotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus Group occasionally associated with food poisoning. Int. J. Syst. Evol. MicroBiol. 63, 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.030627-0 (2013).

Chauhan, S., Kumar, A., Singhal, A., Tyagi, J. S. & Krishna Prasad, H. CmtR, a cadmium-sensing ArsR-SmtB repressor, cooperatively interacts with multiple operator sites to autorepress its transcription in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 276, 3428–3439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07066.x (2009).

Saha, R. P. et al. Metal homeostasis in bacteria: the role of ArsR-SmtB family of transcriptional repressors in combating varying metal concentrations in the environment. Biometals: Int. J. role Metal ions Biology Biochem. Med. 30, 459–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-017-0020-3 (2017).

Xu, C. & Rosen, B. P. Dimerization is essential for DNA binding and repression by the ArsR metalloregulatory protein of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 15734–15738. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.25.15734 (1997).

Zhi, F. et al. An ArsR transcriptional regulator facilitates Brucella sp. Survival via regulating self and outer membrane protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910860 (2021).

Schaeffer, P., Millet, J. & Aubert, J. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 54, 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.54.3.704 (1965).

Macaluso, A. & Mettus, A. M. Efficient transformation of Bacillus thuringiensis requires nonmethylated plasmid DNA. J. Bacteriol. 173, 1353–1356. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.173.3.1353-1356.1991 (1991).

Zhang, X. et al. A Novel Regulator PepR regulates the expression of dipeptidase gene pepV in Bacillus thuringiensis. Microorganisms. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms12030579 (2024).

Sambrook, B. J. & Russell, D. W. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual. 3rd edn. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, 2015).

Lereclus, D., Arantes, O., Chaufaux, J. & Lecadet, M. Transformation and expression of a cloned delta-endotoxin gene in Bacillus thuringiensis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 51, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1097(89)90511-9 (1989).

Agaisse, H. & Lereclus, D. Structural and functional analysis of the promoter region involved in full expression of the cryIIIA toxin gene of Bacillus thuringiensis. Mol. Microbiol. 13, 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00405.x (1994).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFE0116500), Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-CSCB-202402), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program, grants No. 32072499 and No. 32372623).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.S. and X.Z. designed the experiments. X.Z., Y.C., T. Y., and H.W. performed the experiments. Y.L. and L.G. gave good advice on RNA extraction experiments. X.Z. and F.S. analyzed the results. X.Z. wrote the manuscript. F.S., Q.P., and J.L. gave good advice on the writing of the manuscript. F.S. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

41598_2024_76694_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Strains and plasmids used in this study. Table S2. Oligonucleotide primers used in this study. Table S3. The promoter of target genes from CdsR-binding DNA contain a conserved sequence.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Chen, Y., Liu, Y. et al. A novel regulator CdsR negatively regulates cell motility in Bacillus thuringiensis. Sci Rep 14, 25270 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76694-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76694-2