Abstract

Using acrylic acid advanced ester and styrene as raw materials, the long-chain polyester polymer, polyacrylic acid advanced ester-styrene pour point depressant (P-PPD), was synthesized by molecular design, and its structure was characterized by infrared spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance. In addition, this study experimentally investigated the effect of P-PPD on the phase equilibrium and induction time of natural gas hydrate inhibitors in deionized water (DW) and crude oil/water (O/W) systems, respectively. Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and mono ethylene glycol (EG) were selected as representatives of kinetic hydrate inhibitor (KHIs) and thermodynamic hydrate inhibitor (THIs), respectively. The results exhibit that P-PPD played a sight role in the phase equilibrium of hydrate, while the addition of P-PPD significantly prolonged the induction time of methane hydrate both in O/W + PVP, OW + EG and O/W + PVP + EG system, indicating that the addition of as-synthesized PPD has a synergistic inhibition effect on the nucleation ability of methane hydrate and can prevent hydrate from formatting during oil and gas transport process, and thus guarantee the flow assurance. The findings of this work will provide a data reference for the hybrid use of hydrate inhibitors and pour point depressants in oil and gas transport.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gas hydrate is a kind of nonstoichiometric crystalline substance with a cage-like structure that forms from small gaseous water molecules at low temperatures and high pressures1,2. Water molecules are complexed into water cages with hydrogen bonds. The gas molecules trapped in cages are held together by hydrogen bonds and are stabilized by van der Waals forces2,3. In nature, gas hydrates typically exist under extreme environmental conditions such as permafrost and deep sea. Typical hydrate sources observed under deep-sea conditions include CH4, CO2, C2H6, C3H8, H2S, i-C4H10, and other small-chain hydrocarbons4,5,6. The abundance of small gas and water molecules that tend to be present near or across the entire deep-sea oil and gas extraction site and low-temperature, high-pressure environment affords thermodynamically favorable conditions for gas hydrate generation, which leads to the formation of caged hydrates in oil and gas transportation pipelines7,8,9.

Natural gas hydrates can cause pipeline flow problems9,10. They often clog them and slow down the production of petroleum. Methanol and ethylene glycol (EG) are thermodynamic inhibitors (THIs) to control natural gas hydrates in petroleum production lines11,12. These inhibitors alter water activity and thus reduce the thermodynamic generation temperature of gas hydrates13,14. However, thermodynamic inhibition requires a high dosage of inhibitors and can be very costly. Low-dosage hydrate kinetic inhibitors (KHIs), for instance, Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and polyvinylcaprolactam (PVCap), etc. are a class of water-soluble macromolecules in which the polymerization units comprise hydrophobic alkane chains and hydrophilic carbonyl groups15,16. The inhibitors hinder the bulk production of hydrates by preventing the growth of hydrate nuclei via adsorption. The dosage of kinetic inhibitors ranges from 1 to 5% in contrast to thermodynamic inhibitors17,18. The polar functional groups in hydrate inhibitors can be adsorbed on the hydrate unit cells surface through hydrogen bonds, occupying the position of water molecules, while hydrophobic polymer chains can prevent water molecules from approaching hydrate unit cells, thereby inhibiting the growth of hydrate. The inhibition principle of such polymer hydrate inhibitors has been verified in all structure of I, structure II, and structure H19,20,21. Kinetic inhibitors are generally mixed with thermodynamic inhibitors to prevent gas hydrate blockages more effectively22,23. In addition to avoiding blockages during oil and gas transmission, it was reported that the addition of a small amount (0.1–0.5%) of pour point depressants (PPD) could prevent pipeline deposition of recombinant components of crude oil24,25.

The chemical modification of waxy crude oil by adding small doses of polymer-based pour point depressants effectively improves the efficiency of natural oil pipeline transmission26,27,28. Widely used polymer-based PPD include ethylene polymers and their copolymers, comb-like polymers, as well as polymers containing long-chain alkyl groups. PPD is generally composed of oil-soluble organic compounds or polymers29,30,31. In addition, polymer-based PPD molecules generally contain polar and non-polar parts, and non-polar groups (usually long alkyl chains) can be co-precipitated with wax by van der Waals forces and interact with solubilized wax molecules32,33. The actual crude oil transport is a process of mixed injection using pour point depressants and gas hydrate inhibitors. During easy oil transport, mixing multiple chemicals affects the effectiveness of gas hydrate inhibition17,34. Negatively charged clay particles chemically and physically adsorb kinetic inhibitors, and the adsorbed inhibitors lose their ability to inhibit hydrates35,36. Acidification of the crude oil transport environment can cause the polar groups of the hydrate kinetic inhibitor polymer to be occupied by the hydrogen protons and weaken the inhibitor’s effect on gas hydrates37,38. There is a lack of studies on the impact of the addition of PPD to crude oil systems on gas hydrate inhibition. The effect of hydrate inhibitors on gas hydrate inhibition in two-phase systems where multiple inhibitors coexist above the freezing point of crude oil and in three-phase systems with recombined crude oil-water (O/W) systems below the freezing point is a fundamental parameter for the use of additives for oil and gas transport safety39,40.

In this study, we designed and synthesized polyacrylic acid advanced ester-styrene PPD (P-PPD) product. The phase equilibrium conditions of CH4 hydrate in P-PPD and gas hydrate inhibitor systems were investigated by lowering the temperature while maintaining a constant volume. We also studied the induction time (tind) of CH4 hydrate in the O/W, O/W + PVP, O/W + PVP + P-PPD, O/W + EG, O/W + EG + P-PPD, O/W + PVP + EG and O/W + PVP + EG + P-PPD systems. The results verified that the as-synthesized PPD effectively enhanced the inhibitory influence of gas hydrate inhibitors in crude oil emulsification system.

Materials and methods

Materials

The advanced esters of acrylic acid (purity > 99.7%), styrene (purity: 99%), vinyl acetate (purity: 99%), maleic anhydride (purity > 99.0%), benzoyl peroxide (purity: 75%), carbon tetrachloride (purity > 99.90%), methanol (purity: purity > 99.5%), cyclohexane (purity > 99%), azo diisobutyronitrile (purity: 98%) used in the experiment are all provided by Energy Chemical Reagent Company, and the reagents used are directly used without further treatment. Methane gas (purity > 99.90%) and deionized water (DW) prepared through the purified water instrument with an electrical conductivity of 18.5 MΩ·cm− 1 were used to form hydrates. PVP with a purity of 98.0 mol% and a molecular weight ranging from 3000 to 7000, and EG (monor ethylene glycol) with 99% purity were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., China. The crude oil was available from the State Key Laboratory of Natural Gas Hydrates. The density, waxing point, and freezing point of crude oil are 0.854 g/cm3, 17.5 °C and 4.3 °C, respectively.

Synthesis procedure and reaction formula of P-PPD

The advanced acrylic ester and styrene (monomer ratio of 3:2) were added to a three-mouth flask equipped with a reflux condenser and agitator, heated until melted, and the solvent toluene was added and stirred to make the system mix evenly. Under the protection of nitrogen, 1.0% wt of benzoyl peroxide initiator was added to the reaction system after stirring and heating to the polymerization temperature (85 °C), and the reaction was terminated after 6 h. After the temperature was reduced to room temperature, the polymerization product was washed with methanol many times, and the precipitate was vacuum filtered and dried at 70 °C in vacuum for 4 h to obtain polyacrylic acid advanced ester-styrene PPD (P-PPD) product. The reaction formula is shown in Fig. 1.

Analysis methods

Infrared spectrometer, nuclear magnetic resonance hydrogen spectrometer, and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) are utilized to determine the molecular structure of P-PPD. Saturates, aromatics, resins, and asphaltenes (SARA) components were separated through the solvent precipitation and chromatographic column (SPCC) method based on ASTM D 412441, and the detailed process is exhibited in Fig. 2. The C, H, S, and N concentrations in each component of saturates, aromatics, and gums were quantified using elemental analysis. The oxygen content was obtained by using the difference reduction method. Fourier transforms infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) within 500–3500 cm− 1 was used to study the chemical properties of the inhibitor and pour point depressant using the KBr pellet technique. 10 mg P-PPD was dissolved in deuterated chloroform, centrifuged at 8000 rpm and 4 °C for 1 min, and 200 µL transferred into 3 mm outer diameter NMR tubes using a glass pipet, and the 1H NMR spectra of P-PPD was obtained on a 500 MHz NMR spectrometer Bruker Avance III 500. The elemental compositions of crude oil were investigated by elemental analyser (Vairo EL cube03030402, Elementar Analysensysteme, Germany), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC-204, NETZSCH, Germany) was employed to investigate the pour point of crude oil.

Experimental procedure

Test method for the hydrate phase equilibrium

The CH4 hydrate phase equilibrium is determined based on the constant volume method in which the pressure varies with temperature. 100 mL of solution was transferred to the autoclave with a volume of 150 mL, the air was removed from the system with a vacuum pump, and the system was flushed with the experimental gas three times. The gas booster pump was utilized to pressure the gas in the system to the desired pressure, and residual gas was removed. The cooling liquid in the refrigeration system was a glycol-water mixture, and the stirrer speed was set to 500 rpm. Four temperature control processes were carried out during the test: (1) Rapid cooling process: pressure-temperature data show a linear pattern (cooling rate of 5 K/h), and hydrates are not generated in this process; (2) Generation of hydrates starts with a sudden drop in the system pressure and a sudden increase in the system temperature. The system then starts to warm up after a large amount of hydrates is generated, and the system pressure decreases by 1 MPa; (3) The system goes through a rapid heating process after a large amount of hydrate is generated (heating rate of 5 K/h); and (4) The system is slowly heated when approaching the hydrate phase equilibrium point to restore the hydrate decomposition system to its initial state. In step (4), the system pressure is kept at a steady state at each temperature point by maintaining the temperature for 2 h with every increment of 0.2 K. The pressure sensor and temperature sensor modes used in this experiment are GE Druck UNIK5000 and PT100 with an accuracy of ± 0.04% FS and 0.1 K, respectively.

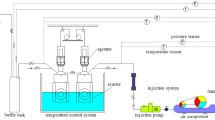

Test method for the hydrate induction time

A pressure vessel made of 316 stainless steel with a maximum pressure of 15 MPa and a volume of 150 mL (diameter 10 cm, height 19 cm, and thickness 0.75 cm) was designed to determine the tind of CH4 hydrates. The schematic diagram of the high-pressure autoclave system is exhibited in Fig. 3. Both sides of the autoclave were equipped with transparent glass windows for the observation of hydrate formation. Refrigerated liquid circulator (PolyScience, USA) was utilized to control the system temperature. A cylindrical rotor with a length and diameter of 3 cm and 50 mm coated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) was used as a stirrer. The temperature sensor mode and pressure sensors with accuracy of ± 0.01 °C and ± 0.01 MPa, respectively, were utilized to monitor the temperature and pressure in the pressure unit, respectively. The cooling process was as follows: (1) 2% PVP, 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD, 5% EG, 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD, and 2% PVP + 5% EG + 0.01% P-PPD was added to the autoclave containing an oil-water mixture with a water content of 30%, respectively; (2) The vacuum pump was used for 10 min and CH4 gas was added until the pressure reached 3 MPa; then, the process was repeated; (3) The pressure in the autoclave was increased to 12 MPa. The stirrer was started, and the speed was adjusted to 500 revolutions per minute; (4) The autoclave was cooled from 10 to 0.5 °C at a rate of 2 °C/h, and the temperature was kept constant for 1000 min; (5) The autoclave pressure and temperature were recorded on the computer. To reduce the experimental error, the experiments were conducted 5 times, and the error bars are the standard deviation (SD) of replicates. In addition, between each tind run, the sample was refreshed to eliminate the memory effect.

Results and discussion

Structure characters of P-PPD

The infrared spectroscopic characterization of the P-PPD was carried out, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. In the infrared spectrum, the telescopic peaks of CH2 and CH3 appeared at 2925 cm− 1 and 2854 cm− 1, respectively42. The characteristic peak of ester carbonyl C = O appeared at 1740 cm− 1. The C-O-C antisymmetric stretching vibration and symmetrical stretching vibration peak appeared at 1242 and 1127 cm− 1, respectively43. The olefin C = C absorption peak at 1640 cm− 1 in acrylates disappeared, and the absorption peaks of double bonds in the benzene ring appeared at 1607 cm− 1, 1460 cm− 1, and 1375 cm− 144. The in-plane vibration absorption peaks of olefin CH2 at 990 cm− 1 disappeared, and the characteristic peak of polymerized long carbon chains characterizing -[-CH2-CH-CH2-CH]-(x > 4) appeared at 723 cm− 1, indicating that the double bond in styrene and acrylate was broken and a new polymer was formed45. The peak at 783 cm− 1 and 849 cm− 1 contributed to the substituted rocking vibration absorption peak and out-of-plane bending vibrations of C-H bond in the aromatic ring, which indicates that styrene was involved in the reaction46.

The 1H NMR spectrum is shown in Fig. 5, in which the characteristic hydrogen in the structure is marked in the spectrum, the chemical shift of the characteristic hydrogen is reasonable, and the integral value is correct, confirming the polymer structure47,48,49. It can be observed that the characteristic peak of the C = C double bond does not appear in the spectrum, indicating the polymerization was complete. In addition, the GPC analysis of P-PPD was performed and the results are as exhibited in the inset figure of Fig. 5, in which the Mn and Mw of the polymer were calculated as 65,899 and 90,202, respectively.

Physical properties of crude oil

There are many components in crude oil, and there may be interaction forces between components, PPD, and hydrate inhibitors, which can affect the inhibitory effect, so it is necessary to identify different chemical components in crude oil by SARA analysis. The results are exhibited in Table 1. It shows that the wax content was 3.573 wt%, the asphaltene content was 1.174 wt%, and the recombinant component content was low.

The element analysis results are shown in Table 2, and it can be found that the C, H, S, O, and N compositions of saturates and aromatics are similar, and only have minor differences. In contrast to the saturates and aromatics, the proportions of carbon and hydrogen atoms in gums are higher, which indicates that the aromatic and saturated hydrocarbons contain more heteroatoms.

Effect of pour point depressants on the systemic equilibrium of methane hydrate inhibitors

To evaluate the effect of pour point depressants on the thermodynamics of gas hydrate generation, the phase equilibrium conditions of CH4 hydrate for the systems DW, DW + 2% PVP, DW + 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD, DW + 5% EG, DW + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD, DW + 2% PVP + 5% EG, and DW + 2% PVP + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD were obtained at pressures ranging from 3 to 10 MPa and temperatures varying from 276 to 290 K, as shown in Fig. 6. It shows that adding 2% PVP and 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD to DW leads to a smaller differential phase equilibrium pressure change in CH4 hydrate compared with the DW system. This is because hydrate kinetics inhibition primarily hindered hydrate nucleation generation, which only played a small role in the hydrate thermodynamics. EG, as a thermodynamic inhibitor of hydrate, its main function is to prevent and control water and hydrate generation by changing the hydrate generation conditions. Therefore, the CH4 hydrate phase equilibrium conditions of the systems containing EG are significantly more demanding than those without EG.

In addition, the phase equilibrium results in different inhibitor and pour point depressant systems are shown in Table 3. It shows that the DW + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD, DW + 2% PVP + 5% EG, DW + 2% PVP + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD systems change less than the DW + 5% EG methane hydrate system. Therefore, it can be deduced that the phase equilibrium conditions of CH4 hydrate mainly depend on EG, and the addition of PVP and PPD has only a minor effect on the phase equilibrium conditions.

The P-T conditions for the equilibrium of phases in the H-Lw-V system can be described by a Clapeyron-type equation50.

where P is the pressure in MPa and P is the temperature in K. A and B are parameters. The experiment data obtained in this study are plotted in Fig. 6. Data points were fitted to Eq. (1), yielding A and B for each inhibitor as shown in Table 4. The high R2 values for each fitting listed in Table 4 suggest that the Clapeyron-type equation can well predict the phase equilibrium of CH4 hydrate in solutions with different inhibitor.

Hydrate inhibiting effects of PPD and PVP mixtures in crude oil–water systems

The induction time of CH4 hydrate was used to evaluate the effects of inhibitors on hydrate inhibition. The tind of CH4 hydrate in different systems was measured by reducing the temperature while maintaining a constant volume. When CH4 hydrate was generated in large quantities, a large amount of heat was released in a short period, which contributed to a significant increase in the system temperature. The temperature then returned to the set temperature with the exchange of heat in the system, as shown in Fig. 7. It shows that the temperature instantly increased from 0.5 to ~ 4 ℃ when hydrates were generated in large quantities. This significant temperature change indicates that CH4 hydrate was instantaneously generated in large amounts. In addition, based on the hydrate tind measurements, it confirms that the inhibitor significantly hinders the hydrate formation.

The tind statistics of CH4 hydrate in the three systems O/W, O/W + 2% PVP, and O/W + 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD are shown in Fig. 8. It exhibits that all induction times of CH4 hydrate in the three systems are within 400 min. The average tind of CH4 hydrate in the O/W system is 92 min, whereas the tind of CH4 hydrate significantly increased after the addition of 2% PVP CH4 hydrate in O/W. CH4 hydrate was only generated after 205 min. PVP significantly inhibits hydrate nucleation growth, although it does not affect the inhibitor’s effectiveness on hydrate in the O/W system. The tind of CH4 hydrate was delayed to 275 min after adding 0.1% P-PPD to the O/W + 2% PVP system. The tind of hydrate in the O/W + 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD system significantly increased compared with that in the O/W and O/W + 2% PVP systems, which indicates that the addition of the P-PPD has a synergistic inhibitory effect on the nucleation ability of CH4 hydrate.

Hydrate inhibiting effect of pour point depressants, PVP, and ethylene glycol mixtures in crude oil-water systems

During oil and gas transport in the deep sea and extremely cold regions, THIs and KHIs are simultaneously used to prevent and control hydrates. A certain amount of PPD is generally added to the injection to avoid the blockage of pipelines by depositing recombinant components in the crude oil. The effect of gas hydrate inhibitors in a mixed injection system with multiple types of injection agents is one of the leading indicators of hydrate flow safety and regulatory management. Figure 9 shows the CH4 hydrate tind for the systems of O/W containing 5% EG, 2% PVP + 5% EG, and 2% PVP + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD.

Based on Fig. 9, the tind of O/W + 5% EG is 125 min, representing a slight change in the hydrate tind compared with the 92 min of the O/W system shown in Fig. 8. This change is due to EG, which inhibits hydrate generation the most, mainly by altering the phase equilibrium conditions, and inhibiting the nucleation and growth of hydrate. The tind of O/W + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD system increased to 186 min, indicating that P-PPD also played a synergistic inhibiting effect with THIs. Adding 2% PVP to the O/W + 5% EG system significantly enhances the hydrate inhibition, prolonging the hydrate tind to 320 min. In contrast to 205 min in the O/W + 2% PVP system displayed in Fig. 8, the prevention and control of the hydrate tind significantly increased in the mixed system of THIs and KHIs. The tind of CH4 hydrate was delayed to 385 min after adding 0.1% P-PPD to the O/W + 2% PVP + 5% EG system, representing a more significant inhibiting effect on CH4 hydrate compared with the O/W + 5% EG and O/W + 2% PVP + 5% EG systems. All the above results verified that in the mixed oil-water system, adding pour point depressants could effectively enhance the effects of gas hydrate inhibitors, whether it is KHIs, THIs, or mixed KHIs and THIs. This may be because pour point depressants mainly promote dispersion and are rich in many polar functional groups, some of which dissolve in the aqueous phase, inhibit hydrate nucleation by generating hydrogen bond complexes with water molecules, and subsequently inhibit gas hydrate nucleation.

Conclusion

In this study, long-chain polyester polymer, polyacrylic acid advanced ester-styrene pour point depressant (P-PPD) was synthesized by molecular design. The phase equilibrium of hydrate in different systems was determined using the equal gradient temperature increase method in the temperature and pressure ranges of 273.3–84.3 K and 3.6–9.37 MPa, and the results indicate that the phase equilibrium conditions of methane hydrate mainly depend on EG, and the addition of PVP and PPD have only a minor effect on the phase equilibrium conditions. The induction times of CH4 hydrate in the systems O/W, O/W + 2% PVP, O/W + 2% PVP + 0.1% P-PPD, O/W + 5% EG, O/W + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD, O/W + 2% PVP + 5% EG, and O/W + 2% PVP + 5% EG + 0.1% P-PPD with a water content of 30% were determined by lowering the temperature while maintaining a constant volume. The results show that the addition of P-PPD all prolonged the tind in O/W + 2% PVP, O/W + 5% EG, and O/W + 2% PVP + 5% EG systems, indicating that the PPD in the mixed oil-water system synergistically enhances the effect of KHIs, THIs, as well as mixed KHIs and THIs. These experimental results provide data supporting the injection of mixed inhibitors in hydrate to control oil and gas transport in transmission pipelines.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Li, X. S. et al. Investigation into gas production from natural gas hydrate: A review. Appl. Energy 172, 286–322 (2016).

Wang, F. et al. Gas production enhancement by horizontal wells with hydraulic fractures in a natural gas hydrate reservoir: A thermo-hydro-chemical study. Energy Fuels 37(12), 8258–8271 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Nucleation mechanisms of CO2 hydrate reflected by gas solubility. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 10441 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Influence mechanism of interfacial organic matter and salt system on carbondioxide hydrate nucleation in porous media. Energy, 290, 130179 (2024).

Hachikubo, A. et al. Characteristics and varieties of gases enclathrated in natural gas hydrates retrieved at Lake Baika. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 4440 (2023).

Shi, B. et al. Status of natural gas hydrate flow assurance research in China: A review. Energy Fuels 35(5), 3611–3658 (2021).

Wang, Y., Fan, S. & Lang, X. Reviews of gas hydrate inhibitors in gas-dominant pipelines and application of kinetic hydrate inhibitors in China. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 27(9), 2118–2132 (2019).

Akhfash, M., Aman, Z. M., Ahn, S. Y., Johns, M. L. & May, E. F. Gas hydrate plug formation in partially-dispersed water-oil systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 140, 337–347 (2016).

Sa, J. H. et al. Inhibition of methane and natural gas hydrate formation by altering the structure of water with amino acids. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 31582 (2016).

Yang, L. et al. Thermotactic habit of gas hydrate growth enables a fast transformation of melting ice. Appl. Energy 331, 120372 (2023).

Bharathi, A. et al. Experimental and modeling studies on enhancing the thermodynamic hydrate inhibition performance of monoethylene glycol via synergistic green material. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 2396 (2021).

Semenov, A. P. et al. Synergistic effect of salts and methanol in thermodynamic inhibition of sII gas hydrates. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 137, 119–130 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Numerical investigation of the depressurization exploitation scheme of offshore natural gas hydrate: Enlightenments for the depressurization amplitude and horizontal well location. Energy Fuels 37(14), 10706–10720 (2023).

Daraboina, N., Pachitsas, S. & von Solms, N. Experimental validation of kinetic inhibitor strength on natural gas hydrate nucleation. Fuel 139, 554–560 (2015).

Farhadian, A. et al. Waterborne polyurethanes as a new and promising class of kinetic inhibitors for methane hydrate formation. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 9797 (2019).

Dubey, S. et al. Elucidating the impact of thermodynamic hydrate inhibitors and kinetic hydrate inhibitors on a complex system of natural gas hydrates: Application in flow assurance. Energy Fuels 37(9), 6533–6544 (2023).

Liao, B. et al. Development of novel natural gas hydrate inhibitor and the synergistic inhibition mechanism with NaCl: Experiments and molecular dynamics simulation. Fuel 353, 129162 (2023).

Khan, M. S. et al. Effect of ammonium hydroxide-based ionic liquids’ freezing point and hydrogen bonding on suppression temperature of different gas hydrates. Chemosphere 307, 136102 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. The passive effect of clay particles on natural gas hydrate kinetic inhibitors. Energy 267, 126581 (2023).

Bharathi, A., Nashed, O., Lal, B. & Foo, K. S. Experimental and modeling studies on enhancing the thermodynamic hydrate inhibition performance of monoethylene glycol via synergistic green material. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 1–10 (2021).

Sa, J. H., Kwak, G. H., Han, K., Ahn, D. & Lee, K. H. Gas hydrate inhibition by perturbation of liquid water structure. Sci. Rep. 5(1), 1–9 (2015).

Wang Y, et al. Effect of a rapeseed oil derived pour point depressant on the flow properties of the waxy oil from Changqing Oilfield, in E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, Vol. 329, 01051 (2021).

Peng, Z. et al. Effect of the ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer on the induction of cyclopentane hydrate in a water-in-waxy oil emulsion system. Langmuir 37(45), 13225–13234 (2021).

Xie, M. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of benzyl methacrylate-methacrylate copolymers as pour point depressant in diesel fuel. Fuel 255, 115880 (2019).

Sharma, R., Mahto, V. & Vuthaluru, H. Synthesis of PMMA/modified graphene oxide nanocomposite pour point depressant and its effect on the flow properties of Indian waxy crude oil. Fuel 235, 1245–1259 (2019).

Pal, B. & Naiya, T. K. Application of synthesized novel biodegradable pour-point depressant from natural source on flow assurance of indian waxy crude oil and comparative studies with commercial pour-point depressant. SPE J. 27(01), 864–876 (2022).

Fan B, et al. Experimental study on tribological properties of polymer-based composite nano-additives suitable for armored vehicle engine lubricating oil, in MATEC Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, Vol. 358, 01009 (2022).

Xie, Y. et al. Effect of shear on durability of viscosity reduction of electrically-treated waxy crude oils. Energy 2023, 128605 (2023).

Binks, B. P. et al. How polymer additives reduce the pour point of hydrocarbon solvents containing wax crystals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17(6), 4107–4117 (2015).

Xu, J. et al. Effect of polar/nonpolar groups in comb-type copolymers on cold flowability and paraffin crystallization of waxy oils. Fuel 103, 600–605 (2013).

El-Segaey, A. A. et al. Comparative study between a copolymer based on oleic acid and its nanohybrid for improving the cold flow properties of diesel fuel. ACS Omega 8(11), 10426–10438 (2023).

Qasim, A., Khan, M. S., Lal, B. & Shariff, A. M. A perspective on dual purpose gas hydrate and corrosion inhibitors for flow assurance. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 183, 106418 (2019).

Ibrahim, M. A. & Saleh, T. A. Partially aminated acrylic acid grafted activated carbon as inexpensive shale hydration inhibitor. Carbohydr. Res. 491, 107960 (2020).

Lee, W., Shin, J. Y., Kim, K. S. & Kang, S. P. Synergetic effect of ionic liquids on the kinetic inhibition performance of poly (N-vinyl caprolactam) for natural gas hydrate formation. Energy Fuels 30(11), 9162–9169 (2016).

Liu, Y. et al. Understanding the inhibition performance of kinetic hydrate inhibitors in nanoclay systems. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130303 (2021).

Moslemizadeh, A., Aghdam, S. K., Shahbazi, K., Aghdam, H. K. Y. & Alboghobeish, F. Assessment of swelling inhibitive effect of CTAB adsorption on montmorillonite in aqueous phase. Appl. Clay Sci. 127, 111–122 (2016).

Borgund, A. E. Crude Oil Components with Affinity for Gas Hydrates in Petroleum Production (The University of Bergen, 2007).

Bavoh, C. B. et al. Ionic liquids as gas hydrate thermodynamic inhibitors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60(44), 15835–15873 (2021).

Yang, L., Falenty, A., Chaouachi, M., Haberthür, D. & Kuhs, W. F. Synchrotron X-ray computed microtomography study on gas hydrate decomposition in a sedimentary matrix. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17(9), 3717–3732 (2016).

Wei, R. et al. Long-term numerical simulation of a joint production of gas hydrate and underlying shallow gas through dual horizontal wells in the South China Sea. Appl. Energy 320, 119235 (2022).

Standard A. Standard Test Method for Separation of Asphalt into Four Fractions (ASTM, 2009).

Saikia, B. K., Boruah, R. K. & Gogoi, P. K. FT-IR and XRD analysis of coal from Makum coalfield of Assam. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 116, 575–579 (2007).

Smith, B. C. The Carbonyl Group, Part I: Introduction (2017).

Asemani, M. & Rabbani, A. R. Detailed FTIR spectroscopy characterization of crude oil extracted asphaltenes: Curve resolve of overlapping bands. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 185, 106618 (2020).

Nandiyanto, A. B. D., Ragadhita, R. & Fiandini, M. Interpretation of Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR): A practical approach in the polymer/plastic thermal decomposition. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 8(1), 113–126 (2023).

Chen, Y., Mastalerz, M. & Schimmelmann, A. Characterization of chemical functional groups in macerals across different coal ranks via micro-FTIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Coal Geol. 104, 22–33 (2012).

Mathakiya, I., Rao, P. V. C. & Rakshit, A. K. Synthesis and characterization of styrene–acrylic ester copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 79(8), 1513–1524 (2001).

McHale, R. et al. Efficient synthesis and copolymerization of poly (acrylic acid) and poly (acrylic ester) macromonomers: Manipulation of steric factors. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 206(20), 2054–2066 (2005).

Kartaloğlu, N. et al. Waterborne hybrid (alkyd/styrene acrylic) emulsion polymers and exterior paint applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 20(5), 1621–1637 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. In situ experimental study on the effect of mixed inhibitors on the phase equilibrium of carbon dioxide hydrate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 248, 117230 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Shi, L.H Cao and K. Huang conceived and designed the experiments. S. Shi and H.J Wu carried out the test. L.H Cao, J.Q Liu and J.X Shen contributed to data analysis. T. Sun supervised the project and wrote the paper. K. Huang, H.J Wu, J.Q Liu and Y.S Liu revised and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, L., Huang, K., Wu, H. et al. Synthesis of long-chain polyester polymers and their properties as crude oil pour point depressant. Sci Rep 14, 27028 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76740-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76740-z