Abstract

Cerebellar vermis hypoplasia refers to a varying degree of incomplete development of the cerebellum and vermis. A Saudi family with four affected individuals with cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, facial dysmorphology, visual impairment, skeletal, and cardiac abnormalities was ascertained in this study. Three out of four patients could not survive longer and had died in early infancy. Genetic analysis of the youngest affected was performed by genome-wide homozygosity mapping coupled with whole exome sequencing (WES), followed by Sanger validation. Genome-wide genotyping analysis mapped the phenotype to chromosome 8q24.3. Using an autosomal recessive model, considering deleterious variants with minor allele frequency of less than 0.001 in WES data, a homozygous missense variant (NM_025251.2; ARHGAP39; c.1301G > T; p.Cys434Phe) was selected as a potential candidate for the phenotype. The variant (c.1301G > T) in the ARHGAP39 is in the region of homozygosity on chromosome 8q24.3. ARHGAP39 is a Rho GTPase-activating protein 39 and has been known to regulate apoptosis, cell migration, neurogenesis, and cerebral and hippocampal dendritic spine morphology. Mice homozygous for arhgap39 knockouts have shown premature embryonic lethality. Our findings present the first ever human phenotype associated with ARHGAP39 alteration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cerebellum undergoes extended developmental stages of cellular proliferation, migration of cerebellar neurons, and maturation, which make it susceptible to a broad spectrum of developmental defects. Cerebellar malformations encompass a heterogeneous spectrum of conditions, including cerebellar agenesis (partial or complete absence of vermis and/or hemispheres), cerebellar hypoplasia (the presence of complete cerebellum with congenitally decreased volume of the vermis and/or hemispheres), cerebellar dysplasia (focal or diffuse disorganized development of the cerebellum), and cerebellar atrophy (the presence of complete cerebellum with secondary decreased cerebellar volume)1.

Cerebellar hypoplasia (CBLH) refers to the cerebellar abnormality in which the cerebellum is smaller than usual but has a normal shape2,3. It is a common finding in a highly heterogeneous group of diseases and is caused either by genetic defects or environmental factors4. Radiological examinations reveal various patterns of involvement, including vermis involvement in unilateral CBLH, or involvement of both vermis and hemispheres in global CBLH, or involvement of the pons and cerebellum in pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH)5. Genetic causes of these disorders may include chromosomal aberrations or single gene alterations. There are twenty-two subclinical types of PCH based on the causative genes (Supplementary Table S1). The underlying genetic causes are more important for carrier testing and counselling families to reduce the disease burden in future generations5,6,7. With the recent advances in next generation sequencing technologies, molecular diagnosis of neurodevelopmental and related disorders of cerebellar malformations has been more efficient in consanguineous families8. Offspring of consanguineous marriages have high level of genomic homozygosity. The homozygous genomic stretches are likely harbour disease causing genetic variants. Therefore, studying consanguineous populations considerably increase the likelihood of identification of genetic defects underlying hereditary disorders9.

In this study, we complemented WES analysis with genome-wide homozygosity mapping, followed by Sanger validation. We report a novel homozygous alteration of the ARHGAP39 gene segregating with the disease phenotype of a lethal form of cerebellar vermis hypoplasia in a Saudi Arabian family. ARHGAP39, also known as preoptic regulatory factor-2 (Porf-2) or Vilse, is a member of Rho GTP-activating proteins (RHOGAPs) that plays a vital role in neural development10. Moreover, ARHGAP39 is known to modulate apoptosis, cell migration, neurogenesis, and the morphology of dendritic spines in the brain and hippocampus. Furthermore, it is able to inhibit the proliferation of neural stem cells (NSC)11. Our study establish the first ever association of a human phenotype with the ARHGAP39 gene.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Four individuals, including a 2-month-old affected female (IV:4), an unaffected (IV:5), and both parents (III:1, III:2) from a consanguineous Saudi family, were recruited for this study (Fig. 1). Both her parents (III:1 and III:2) were first-degree cousins. They had a previous history of three children who had died in early infancy. Patients were assessed clinically by a consultant neonatologist at Madinah Maternity and Children Hospital (MMCH) in Almadinah, Saudi Arabia. All of them presented similar clinical histories to the index patient. Radiography (X-ray), ultrasonography (US), echocardiography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed for the affected individual (IV:4) and examined by expert radiologists. Blood samples from all the individuals were collected in a 3 ml EDTA vacutainer after getting parents’ consent. All procedures were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee (REC036-1441) of the College of Medicine, Taibah University Medina, Saudi Arabia.

Genomic DNA extraction for genetic analysis

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from four available individuals (III:1, III:2, IV:4, and IV:5) using the QIAquick DNA extraction kit (Skelton House, Lloyd Street, North Manchester, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Maestrogen, 8275 South Eastern, Las Vegas, USA) was used to assess the quality of the gDNA. A Qubit dsDNA assay was used to determine the concentration of the gDNA sample. Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to check the DNA integrity. All genetic analysis was conducted in the Center for Genetics and Inherited Diseases (CGID), Taibah University Almadinah.

Whole genome SNP genotyping

A whole genome SNP genotyping array was performed using the Illumina iScan platform and the HumanOmni 2.5 M bead chip, genotyping 2.5 million SNPs. Approximately 200 ng genomic DNA from an affected (IV:4) and three unaffected (III:1, III:2, IV:5) members were taken for genotyping as per the protocol described elsewhere12. Common regions sharing homozygosity amongst the affected members were detected through Illumina GenomeStudio and HomozygosityMapper as described earlier13,14.

Whole exome sequencing (WES)

The WES libraries of the index patient (IV:4) were prepared using the SureSelect V6-Post kit. A total of 3 µg of high-quality genomic DNA was diluted with 1X Low TE Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA) in a 1.5 mL LoBind tube to a total volume of 130 µL. The diluted sample was sheared using a Covaris focused-ultrasonicator instrument (Covaris, Inc. 14 Gill Street, Woburn, Massachusetts, USA). Samples were purified by adding 180 µL of AMPure XP beads to each sheared DNA sample, followed by repeated washing with 70% ethanol. A purified, sheared DNA sample was dissolved in 50 µL nuclease-free water. DNA quality and fragment size were assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer and a DNA 1000 Assay. End repair master mix (SureSelect XT Library Prep Kit ILM) was used to repair the ends of sheared DNA, followed by purification with AMPure XP beads. In the next step, 20 µL of dA-tailing master mix was used to add the dA-tail to the 3’ end of the purified end-repaired DNA fragments. Paired-end adaptors (SureSelect Adaptor Oligo Mix) were ligated to the dA-tailed DNA fragments using T4 DNA ligase. The adaptor-ligated library was amplified using SureSelect primers, Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase, 100 mM dNTP mix, and a pre-capture PCR thermal cycler program. The amplified library was purified using AMPure XP beads. At this stage, quality and quantity were assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer and a DNA 1000 Assay. The purified DNA library (750 ng of DNA in a volume of 3.4 µL) from the last step was hybridized with a target specific capture library. After hybridization, the targeted molecules were captured on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1) (ThermoFisher Scientific Inc, Wyman Street, Waltham MA, USA). In the next step, enriched DNA libraries are PCR amplified in a PCR reaction that includes forward primer (SureSelect ILM Indexing Post-Capture primer), reverse primers (SureSelect 8 bp Indexes), Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase, and 100 mM dNTP Mix (25 mM each dNTP). Amplified capture libraries were again purified using AMPure XP beads, followed by an assessment of the quantity and quality of the indexed library DNA using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer instrument and the High Sensitivity DNA Assay kit. A seeding concentration of 1.5 pM was used for Illumina paired end cluster generation on an Illumina NextSeq500 instrument. Illumina VariantStudio software was utilized for annotation and filtration of all the variants15.

Sanger sequencing

Variants of interest were Sanger-sequenced to validate the variants discovered by WES. Additionally, segregation analysis for the candidate variants was also performed using the genomic nucleic acids of all available individuals. Briefly, variants of interest were prioritized, and PCR oligonucleotides for the variants were designed using primer3Plus software for amplification and subsequent Sanger sequencing. BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Friars Drive Hudson, New Hampshire 03051, USA) was utilized for cycle-sequencing reactions according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Analyses of the data were performed with BioEdit sequence alignment editor software (Ibis Biosciences Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics and candidate variant(s) analysis

Computational prediction of the shortlisted variants was carried out through different online available tools such as Mutation Assessor (http://mutationassessor.org), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), PredictProtein (https://predictprotein.org/), FATHMM (http://fanthmm.biocompute.org.uk/), CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), VarSome (varsome.comttp://), and SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/). Variant frequency in the general population was determined using different online databases such as gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), Exome Variant Server (EVS) (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), ExAC Browser (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), 1000 genomes, and 217 in-house exomes from Saudi population. Conservation of the amino acid [p.Cys434Phe] in the different ARHGAP39 orthologs was searched using Homologene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/homologene/).

Results

Clinical details of the patients

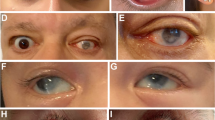

Clinical history

A two-month-old girl (IV-4) was examined in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of the MMCH. The mother underwent caesarean section surgery due to premature rupture of the membrane and foetal distress. The family has a history of the deaths of three girls with multiple congenital anomalies, including cerebellar agenesis and cardiac defects, optic nerve hypoplasia, and limb anomalies including bilateral talipes. Multiple congenital anomalies were also observed in this patient (IV-4), including dysmorphic facial features, deep seated eyes, a small lower jaw, a short neck, increased skin folds, microcephaly, proximal shortening of limb bones, bilateral abduction of hip joints, and bilateral talipes of the foot. All affected individuals needed mechanical ventilation until their deaths in the NICU.

Ultrasonography (US)

Antenatal US examinations showed dilated ventricles. The brain US showed corpus callosum agenesis with dilated bilateral lateral ventricles. However, the echo pattern of the brain parenchyma was normal. The echocardiogram showed a large patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). The abdominal US showed normal internal organs.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Brain MRI revealed a marked hypoplastic cerebellum with a small remnant of vermis, hypoplastic pons, lateral ventriculomegaly (third and fourth), and a dilated cerebellar-medullary cistern (Fig. 2). However, the posterior fossa and the visualized parts of the orbits and peripheral nervous system are within normal limits. Based on the brain MRI, the affected individuals were initially diagnosed as having pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH).

Genetic analysis

Regions of homozygosity (ROH)

Genome-wide SNP data analysis of one affected individual (IV-4) and three unaffected individuals (III-1, III-2, IV-5) identified multiple ROH regions that were greater than 5 Mb. These regions included chromosomes, Chr1; 90 Mb-105 Mb, Chr2; 187 Mb-195 Mb, Chr3; 180 Mb-195 Mb, Chr4; 10 Mb-25 Mb and 182 Mb-188 Mb, Chr5; 0 Mb-6 Mb, Chr6; 0 Mb-8 Mb, Chr8; 12 Mb-27 Mb and 140 Mb-146 Mb, Chr13; 108 Mb-115 Mb, Chr15; 89 Mb-94 Mb, Chr17; 27 Mb-37 Mb, Chr19; 20 Mb-25 Mb and 27 Mb-36 Mb, Chr21; 19 Mb-27 Mb, Chr22; 16 Mb-26 Mb.

WES data analysis and candidate gene prioritization

Exome data was annotated using ANNOVAR16 and annotated Excel files were filtered for variants of interest. In the first step, potential candidate variants in the ROH regions, based on SNP genotyping data, were searched. As our phenotype bears resemblance to pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH), that is why the causative genes of PCH, including SEPSECS and EXOSC4, were first sorted out, which lie within the ROH regions on chromosomes 4 (chr4:25121627–25162204) and 8 (chr8:145133522–145135551), respectively. However, exome data did not identify any variants in the SEPSECS and EXOSC4 genes. Similarly, other candidates of PCH including, TSEN2, TSEN15, TSEN34, TSEN54, EXOSC1, EXOSC2, EXOSC3, EXOSC5, EXOSC6, EXOSC7, EXOSC8, EXOSC9, VPS53, VRK1, SLC25A46, TBC1D23, AMPD2, CHMP1A, TOE1, and RARS2, were all excluded for any potential pathogenic variant. Two homozygous variants in the VPS13B (c.1239T > G; p.Tyr413*) and VPS11 (c.222dupC; p.Tyr75fs) genes were identified; however, these variants were not considered “disease-causing” due to their high minor allele frequency (MAF > 0.001) in the general population.

Once all the known PCH genes were excluded, a search for potential candidate variants was extended using the autosomal recessive model, variants with MAF less than 0.001, and those predicted as “pathogenic or disease-causing” by computational prediction analysis. A rare homozygous missense variant (c.1301G > T; p.Cys434Phe) in the ARHGAP39 gene was identified. Interestingly, ARHGAP39 was located within a region of homozygosity (140 Mb-146 Mb) on chromosome 8q24.3 (Fig. 3).

Sanger validation of ARHGAP39 segregation

Primers sequences (forward: 5’-TCCTGAGCCTGGAGTACAGT-3’ and reverse: 5’-AAAGAGGGCTTTCTGCTCTT-3’) flanking the ARHGAP39 variant (c.1301G > T) were used to amplify the region in the DNA samples from both parents (III-1, III-2), an unaffected (IV-5) and an affected individual (IV-4) with a standard PCR amplification program with an annealing temperature 60 °C. Sequencing analysis revealed autosomal recessive segregation (c.1301G > T) in the family. Both parents are heterozygous; the unaffected child is of wild-type genotype, and the affected individuals is homozygous for the variant (Fig. 4). DNA from seventy four control individuals was screened for the ARHGAP39 variant (c.1301G > T). No single individual was found homozygous for the mutant genotype.

Computational prediction of the variant (c.1301G > T) through different online available tools such as Mutation Assessor (http://mutationassessor.org), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), PredictProtein (https://predictprotein.org/), FATHMM (http://fanthmm.biocompute.org.uk/), CADD (https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), VarSome (varsome.comttp://), and SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) predicted that the variant is damaging and deleterious. Variant frequency in the general population gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), Exome Variant Server (EVS) (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), ExAC browser (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/), 1000 genomes and in 217 in-house exomes from the Saudi population is very low (allele frequency = 0.000004544). The amino acid cysteine at position 434 is highly conserved in the different ARHGAP39 orthologues (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Delineation of the genetics underlying familial cases is successful if more than one affected sibling is available; however, the lethality of the diseases in early infantile life makes it difficult for geneticists to work on a handful of samples for molecular diagnostics. The current study is one of such examples in which parents sought genetic testing for their fourth child, who had an abnormal phenotype, and their three children had already died previously. The clinical presentation of some genetic diseases may vary from prenatal to postnatal, from early childhood to adulthood and a complete phenotype may not appear at birth. Cerebellar malformations have been detected during uterine development, including both genetic and non-genetic disorders. Genetic diagnosis of cerebellar malformations has been successful through whole exome sequencing in autosomal recessive European and Arab families8. Cerebellar hypoplasia is detectable in prenatal life through foetal brain imaging, along with copy number variants through chromosomal microarray analysis17. Foetal brain magnetic resonance imaging for cerebellar vermis anomalies helps in determining the possible outcomes of the neurological impact on embryo development18. None of our patients had any records of prenatal brain imaging, and thus the phenotype was not clear until birth.

The clinical presentation of the affected sibling in this study bore resemblance to previously known PCH phenotypes (supplementary table 2a and b). Early infantile death has been reported in pontocerebellar hypoplasia, hypotonia and respiratory insufficiency syndrome, neonatal, lethal (PHRINL, OMIM 618810) caused by a large deletion on 1p36.33 or point mutation in the ATPase family, AAA domain-containing member 3 A (ATAD3A) gene, and these patients were from Arabs, Iranians, Asians, and South Asians in origin19,20. Herein, extensive genetic investigation and data analysis identified a potential disease causing variant (c.1301G > T) in the ARHGAP39 gene in the affected individual of the family. The gene is located in the homozygous stretch identified in the patient through whole genome genotyping and homozygosity mapping. Variant is very rare in the population databases and it predicted deleterious by multiple in silico tools including MutationTaster, PredictProtein, FATHMM, CADD, VarSome, PolyPhen-2, and SIFT (supplementary Table 3).

ARHGAP39 gene codes for Rho GTPase activating protein 39 also known as RHOGAP, KIAA1688, D15Wsu169e, Vilse, or Prof-2. Genomic size of the ARHGAP39 gene in humans is 77,837 bases, and it is located on the minus strand of chromosome 8q24.3. It has transcripts with 10 and 11 exons coding for 1083aa and 1114aa long proteins, respectively. Its expression is high in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and low in other tissues like the testis, kidney, liver, pancreas, and lungs21. It mediates intrinsic GTPase activity, modulates axon development, regulates central nervous system development, and has a role in reproductive health21,22. According to UniProtKB (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9C0H5) it has four domains: WW domain 1 (25–58), WW domain 2 (63–97), MyTH4 (722–879) and Rho-GAP (890–1078). The two WW domains (WW1 and WW2) on the N-terminus are associated with the binding of the CNK2 scaffold protein via the Robo membrane receptor to regulate dendritic spine formation and axon guidance. It is important for Rac signalling required in spine morphogenesis23, 24. MyTH4 (myosin tail homolog 4) domain is conserved in the tails of several different unconventional myosin. It is involved in intracellular trafficking, cell division, and the contraction of muscles21. Rho-GAP domain is involved in the conversion of the inactive state of GTPases. It is a mediator of EphB1-Rac1 signalling by providing a binding site22. Rho GTPases are Ras released small gene proteins including Rho, Rac, and cdc4221,22.

Homozygous arhgap39 knockout mice have shown premature embryonic death with abnormal organ development and severe dysmorphology. They had poor spatial learning ability, defective spatial working memory, and reduced basal synaptic transmission as compared to control mice23. Overexpression of ARHGAP39 in GG108 cells and ARHGAP39 mutant transfected neurons have shown decreased neurite length, reduced neurite number, increased number of protrusions, restricted axon outgrowth and growth cone expansion22.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an ARHGAP39 gene association with a human phenotype. WES complementation with genome wide homozygosity mapping has been a successful strategy for the identification of novel genes in neurological disorders. The study had the limitation of having only one affected individual; consequently, we recommend that more emphasis be given to newborn screening for the identification of additional variants of ARHGAP39, as children with cerebellar vermis hypoplasia could not survive longer than early infancy. The identification of disease causing variants in novel genes facilitate early detection, enable tailored interventions, and advance our understanding of genetic disorders. These studies hold the potential to significantly improve health outcomes and quality of life.

Data availability

The data files are available upon request. Please contact corresponding author (sbasit.phd@gmail.com) for the data used in the study.

References

Garel, C., Fallet-Bianco, C. & Guibaud, L. The fetal cerebellum: development and common malformations. J. Child. Neurol. 26, 1483–1492 (2011).

Bosemani, T. & Poretti, A. Cerebellar disruptions and neurodevelopmental disabilities. Semin Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 21, 339–348 (2016).

Poretti, A. & Boltshauser, E. Terminology in morphological anomalies of the cerebellum does matter. Cerebellum Ataxias. 2, 8 (2015).

Pidsley, R., Dempster, E., Troakes, C., Al-Sarraj, S. & Mill, J. Epigenetic and genetic variation at the IGF2/H19 imprinting control region on 11p15.5 is associated with cerebellum weight. Epigenetics. 7, 155–163 (2012).

Poretti, A., Boltshauser, E. & Doherty, D. Cerebellar hypoplasia: differential diagnosis and diagnostic approach. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin Med. Genet. 166C, 211–226 (2014).

van Dijk, T., Baas, F., Barth, P. G. & Poll-The, B. T. What’s new in pontocerebellar hypoplasia? An update on genes and subtypes. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 13, 92 (2018).

van Dijk, T., Baas, F., Barth, P. G. & Poll-The, B. T. What’s new in pontocerebellar hypoplasia? An update on genes and subtypes. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 13 (1), 92 (2018).

Aldinger, K. A. et al. Redefining the Etiologic Landscape of cerebellar malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 105, 606–615 (2019).

Erzurumluoglu, A. M., Shihab, H. A., Rodriguez, S., Gaunt, T. R. & Day, I. N. Importance of genetic studies in consanguineous populations for the characterization of Novel Human Gene functions. Ann. Hum. Genet. 80(3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahg.12150 (2016). Epub 2016 Mar 22. PMID: 27000383; PMCID: PMC4949565.

Nowak, F. V. & Gore, A. C. Perinatal developmental changes in expression of the neuropeptide genes preoptic regulatory factor-1 and factor-2, neuropeptide Y and GnRH in rat hypothalamus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 11, 951–958. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00412.x (1999). [PubMed].

Ma, S. & Nowak, F. V. The RhoGAP domain-containing protein, Porf-2, inhibits proliferation and enhances apoptosis in neural stem cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 46, 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2010.12.008 (2011). [PubMed].

Hashmi, J. A., Almatrafi, A., Latif, M., Nasir, A. & Basit, S. An 18 bps in-frame deletion mutation in RUNX2 gene is a population polymorphism rather than a pathogenic variant. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 124–128 (2019).

Albarry, M. A., Alreheli, A. Q., Albalawi, A. M. & Basit, S. Whole genome genotyping mapped regions on chromosome 2 and 18 in a family segregating Waardenburg syndrome type II. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 33, 326–331 (2019).

Albarry, M. A. et al. Novel homozygous loss-of-function mutations in RP1 and RP1L1 genes in retinitis pigmentosa patients. Ophthalmic Genet. 40, 507–513 (2019).

Basit, S. et al. Centromere protein I (CENPI) is a candidate gene for X-linked steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome. J. Nephrol. 33, 763–769 (2020).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Zou, Z. et al. Prenatal diagnosis of posterior fossa anomalies: additional value of chromosomal microarray analysis in fetuses with cerebellar hypoplasia. Prenat Diagn. 38, 91–98 (2018).

Xi, Y., Brown, E., Bailey, A. & Twickler, D. M. MR imaging of the fetal cerebellar vermis: biometric predictors of adverse neurologic outcome. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 44, 1284–1292 (2016).

Desai, R. et al. ATAD3 gene cluster deletions cause cerebellar dysfunction associated with altered mitochondrial DNA and cholesterol metabolism. Brain. 140, 1595–1610 (2017).

Frazier, A. E., Holt, I. J., Spinazzola, A., Thorburn, D. R. & Reply Genotype-phenotype correlation in ATAD3A deletions: not just of scientific relevance. Brain. 140, e67 (2017).

Nowak, F. V. & Porf-2 = Arhgap39 = Vilse: A Pivotal Role in Neurodevelopment, Learning and Memory. eNeuro. 5, ENEURO.0082-18.2018 (2018).

Huang, G. H. et al. Neuronal GAP-Porf-2 transduces EphB1 signaling to brake axon growth. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 4207–4222 (2018).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Important roles of Vilse in dendritic architecture and synaptic plasticity. Sci. Rep. 7, 45646 (2017).

Lim, J., Ritt, D. A., Zhou, M. & Morrison, D. K. The CNK2 scaffold interacts with vilse and modulates rac cycling during spine morphogenesis in hippocampal neurons. Curr. Biol. 24, 786–792 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the volunteer contribution of the family members to this study.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman Center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2022-088.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and FA contributed to clinical investigations and phenotype identification. KR contributed to generate SNP genotyping data and homozygosity mapping. MM and MJ contributed to data analysis, results compilation and manuscript writing. AMA and SB contributed WES data generation and Sanger sequencing. SB designed the study, wrote and finalized the manuscript. All authors agreed on the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants. In the case of children under 16 consents were taken from the parent.

Ethics approval

All procedures were performed according to the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the research ethics committee (REC036-1441) of College of Medicine, Taibah University Medina, Saudi Arabia.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alayoubi, A.M., Alfadhli, F., Mehnaz et al. A homozygous variant in ARHGAP39 is associated with lethal cerebellar vermis hypoplasia in a consanguineous Saudi family. Sci Rep 14, 25291 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77541-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-77541-0