Abstract

Identifying individuals with tuberculosis (TB) with a high risk of onward transmission can guide disease prevention and public health strategies. Here, we train classification models to predict the first sampled isolates in Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission clusters from demographic and disease data. We find that supervised learning, in particular balanced random forests, can be used to develop predictive models to identify people with TB that are more likely associated with TB cluster growth, with good model performance and AUCs of ≥ 0.75. We also identified the most important patient and disease characteristics in the best performing classification model, including host demographics, site of infection, TB lineage, and age at diagnosis. This framework can be used to develop predictive tools for the early assessment of potential cluster growth to prioritise individuals for enhanced follow-up with the aim of reducing transmission chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health concern, causing around 1.3 million deaths in 20221. The World Health Organization’s “End TB Strategy” set out to eradicate the global TB epidemic by 20352; unfortunately, many countries are currently falling behind targets. The early diagnosis of people with infectious TB disease one core component of reducing TB incidence3. Prioritizing interventions for individuals and groups with a high risk of onward transmission can maximise the impact and cost-effectiveness of public health strategies, such as active case finding and TB preventive therapy, to reduce the spread of TB disease and prevent outbreaks.

Transmission of TB from one individual to another can be complex, and depends on the host, pathogen, and environment. Factors associated with the bacteria itself, such as the MTBC lineage, antimicrobial resistance, and the presence of mutations associated with virulence and transmissibility can all contribute to the increased transmission of certain strains4,5,6. Additionally, environmental and socio-economic conditions can increase the risk of exposure to TB and play a role in transmission7, particularly in low-burden settings where the likelihood of incidental contact with infectious individuals is low.

Identifying host and pathogen characteristics that are associated with the growth of transmission clusters within a population can guide efforts to interrupt the spread of TB. Supervised learning methods can find patterns in complex datasets and build models to accurately predict outcomes in new data. This represents an opportunity to use these approaches in combination with retrospective analysis of past outbreaks to develop predictive models of TB cluster growth from patient demographic and clinical characteristics. A previous study explored the use of machine learning approaches to predict the excess growth of TB transmission clusters in the USA8, finding that cluster characteristics prior to growth (e.g., a shorter timing between cases) were more important model predictors than patient or disease characteristics. Further developing tools that stratify risk of cluster growth soon after TB diagnosis using clinical information would help prioritize timely public health action for high-risk networks, such as more intensive contact tracing or mass screening.

Here, we develop predictive models to distinguish between people with TB that are associated with cluster growth versus people not associated with cluster growth using patient demographic and disease characteristics. We tested multiple supervised learning models using a real-world dataset of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) whole genome sequence (WGS) data from British Columbia, Canada, a low incidence region of ~ 6/100,000 population9. We assess machine learning, deep learning, and logistic regression approaches to classify the first two isolates collected from transmission clusters using patient demographic and disease characteristics. In addition, we assess the performance of these models when trained to discriminate between the first people associated with larger TB clusters (here defined as clusters of ≥ 3 individuals) and those associated with smaller clusters (here defined as clusters of < 3 individuals) to identify potential characteristics associated with TB cluster growth.

Results

Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission clusters from British Columbia

A total of 2588 persons with culture-positive TB were identified in British Columbia, Canada between 2005 and 2015 for whom demographic, clinical and bacterial isolate data were available. Mtb whole genome sequence data were obtained for 1329/1337 isolates collected between 2005 and 2014 that shared a MIRU-VNTR genotyping pattern with at least one other isolate; all isolates with a unique MIRU-VNTR pattern (N = 1010) in this period were not sent for further sequencing and were coded as non-clustered in this study. WGS data were available for 236/241 TB culture-positive individuals in 2015.

We found that 656/2575 (25.5%) of isolates clustered with at least one other isolate using a 12 SNP threshold. This was lower than previous estimates in BC when calculated using lower resolution genotyping methods (MIRU-VNTR)10. There were 112 transmission clusters overall ranging in size between 2 and 82 isolates; of these 65/112 (58%) clusters contained two isolates and 17 clusters were of size ≥ 5. Varying the pairwise SNP distance threshold to link isolates did not change the size or composition of clusters significantly. At a 5 SNP threshold, 107 clusters were identified with 598/2575 (23.2%) of isolates in clusters and at a 20 SNP threshold there were 127 clusters with 703/2575 (27.3%) of isolates in clusters; both thresholds identified the same largest cluster comprising the same 82 isolates.

Classification models

The performance of six supervised learning models (balanced random forest, balanced bagging, balanced logistic regression, LightGBM, TabNet, and a neural network) was evaluated in four classification tasks. The tasks were: (A) discriminating between the first two isolates by collection date in transmission clusters against non-clustered isolates, (B) discriminating between the first two isolates by collection date in transmission clusters and all other collected isolates (both non-clustered isolates and clustered isolates that were collected after the first two isolates), (C) discriminating between the first two isolates by collection date in larger clusters, and both smaller clusters and non-clusters, and D) discriminating between the first two isolates by collection date in larger clusters and isolates in smaller clusters. Mtb isolates collected between 2005 and 2011 were included as training data and isolates collected in 2012 and 2013 as the test dataset.

Figure 1 shows ROC curves and AUC values for each tested approach in four classification tasks. We found that most models were able to predict the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters in the test data against non-clustered isolates (task A) with good performance (AUC > 0.7). The best performing model for this task, balanced random forest had an AUC of 0.82, showing strong discrimination, followed by LightGBM, balanced logistic regression, and the neural network (AUC 0.79) (Fig. 1A). However, this strong model performance may have been driven by the models correctly distinguishing between people belonging to a transmission cluster and those that were non-clustered. Therefore, we next assessed the accuracy in distinguishing between the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters in a dataset that included both non-clustered isolates and all other clustered isolates with collection dates later than the first two isolates (task B). Again, the balanced random forest model achieved a good performance with an AUC of 0.75. (Fig. 1B).

ROC curves and AUC scores for the four classification tasks. (A) distinguishing between the earliest two clustered isolates and non-clustered isolates, (B) distinguishing between the earliest two clustered isolates and all other isolates, (C) distinguishing between the earliest two isolates in clusters of size ≥ 3 and both non-clustered isolates and isolates in clusters of two individuals, and (D) distinguishing between the earliest two isolates in clusters of size ≥ 3 vs. isolates in clusters size = 2.

We next aimed to classify the earliest isolates in larger clusters (n ≥ 3) against smaller clusters (n = 2) and non-clustered isolates to determine if there were characteristics that predicted larger clusters (task C). We found that LightGBM achieved the best performance (AUC = 0.86), followed by balanced logistic regression (AUC = 0.85) and balance random forest (AUC = 0.84) (Fig. 1C). Unfortunately, none of the tested models achieved good discrimination when predicting growth to larger clusters when compared with smaller clusters (task D) (Fig. 1D). In this task, the training and test datasets were significantly smaller than tasks A–C, with the test data containing only 34 isolates compared to 471 (33 positive class) in task A, 391 (33 positive class) in task B, and 391 (9 positive class) in task C, and a training dataset of 164 isolates compared to 1640 (163 positive class) in task A, 1339 (163 positive class) in task B, and 1339 (78 positive class) in task C.

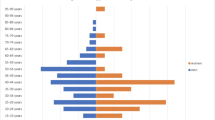

We identified the patient-level demographic and disease characteristics that contributed most towards the classification in the best performing model overall, balanced random forest, using feature selection for tasks A to C. We found that patient demographic (origin) and site of infection were the features that were the most important to the classification models in predicting the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters, and this was consistent across tasks A to C. The major TB lineage of the infection was also found to be an important feature in these tasks. The full rankings of feature importance for tasks A to C are shown in Supplementary fig. S1. Partial dependence plots were calculated to determine whether specific features had a positive or negative impact on the prediction of the positive response variable (Fig. 2). We found that Canadian-born individuals were more likely to represent the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters in all tasks. Individuals with pulmonary TB were also more likely to be the earliest isolates in clusters in these tasks. Conversely, those aged over 60 were negatively associated with a positive response variable and thus were less likely to represent the earliest isolates in clusters in tasks A–C.

Sensitivity analysis

Finally, we found that the good performance of the random forest models in the main analysis was maintained in a sensitivity analysis. Supplementary fig. S2 shows the results of the balanced random forest model for classification tasks A, B, and C, with 100 random partitions of the complete 2005 to 2013 dataset using a ratio of 80:20 training to test data. This model performed similarly when trained on these data compared to the original analysis using the 2005–2011 training data and 2012–2013 test data (AUC 0.75–0.81 vs. median AUCs 0.73–0.90), showing that the choice of partitioning the training and test data by collection date did not influence model performance. We also tested the balanced random forest model on tasks A, B, and C when the response variable was randomly assigned (permuted); in this case we would expect models not to perform well as there is no signal to be found. Indeed, the model achieved poor discrimination in all tasks (median AUCs 0.49–0.51, Supplementary fig. S3, supporting our results that we can predict the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters using specific characteristics in these individuals as shown by the main analysis.

Discussion

Here, we have used the demographic and disease characteristics of people with TB to predict those likely to be associated with larger TB (n ≥ 3) clusters. Using samples collected between 2005 and 2011, we were able to train classification models to predict which people are associated with larger clusters in 2012 and 2013 and those that would likely not be associated with larger clusters. Recently, machine learning has been used in TB research to improve disease diagnosis, for example the automated detection of lesions on chest x-rays11 and the bacteriologic confirmation of TB in children12. Here, we have shown that classification models, including machine learning approaches, can be used to classify individuals with TB that represent a higher or lower risk of belonging to a large transmission cluster through shared demographic and disease characteristics. Our study demonstrates the utility of supervised learning models, coupled with whole genome sequencing data, for developing clinically informative tools for the early detection of growing transmission clusters that can be scaled to incorporate large, complex datasets that include many individuals and associated metadata.

Previous work found that the timing between infections was an important predictor for excess growth in TB transmission clusters from the USA8, though they did not find clinical and patient demographic information to be strong predictors of cluster growth in this setting. In contrast, we found that specific patient demographic and disease characteristics were informative in our models for predicting which individuals were associated with cluster growth beyond the first two people identified and did not find that timing between diagnoses was an important feature. These differences may be due to the higher resolution WGS transmission clusters used in our study compared with the genotypically-derived clusters (through spoligotyping and MIRU-VNTR analysis) in the previous work, or through epidemiological differences between the countries. Further work using the framework demonstrated here that includes transmission clusters from multiple locales can assess whether these models can be generalizable or if explicit models are required to be built in each setting.

We found that the balanced random forest model was able to distinguish between the first two people detected in a TB clusters of all sizes compared to unclustered individuals with good discriminatory power from patient-level characteristics (tasks A and B). We could also classify isolates that would form larger clusters (with three or more isolates) against non-clustered isolates and isolates in smaller clusters of just two individuals (task C), suggesting that it is possible to identify clusters that will expand further after the second individual is detected. While most clusters beginning in 2012 and 2013 contained just two people, there was evidence of cluster growth from 2012 to 2015 from 27% of these clusters. The individuals representing the earliest TB diagnoses in the transmission clusters could have been prioritised for investigation using the models presented here to reduce the probability of cluster growth. The modelling framework presented here can be used to help direct resources for epidemiological investigations, which can be costly and labour intensive, and highlight individuals to prioritise for follow-up that may have a higher risk of initiating secondary infections and larger transmission clusters.

There were differences in the model performance of the tested approaches, and we found that the balanced random forest model obtained the best performance overall. The AUC values of the classification models reported here, and the models themselves, are likely to be specific to our TB population, which is in a low-incidence region with high active case finding and TB preventive therapy13. Further limitations include the absence of data in our analysis on sputum smear microscopy, drug use disorder, and other potential social determinants that may impact transmission such as membership of congregate housing or large households, along with limited follow-up time to fully characterize transmission. These factors have previously been reported to increase the risk of TB transmission7,10 and inclusion of these factors would likely impact the performance of the tested classification models. Additionally, the transmission clusters used here were somewhat simple in their construction, with collection dates used to identify individuals that represented the first two hosts in transmission clusters and equal probability of onward transmission from these individuals. The models presented here may be refined by using well-characterized symptom onset times to characterize the people that would have become infectious first and reconstructing full transmission networks to infer which individuals likely led to secondary infections later in the transmission cluster.

In task D we were not able to discriminate between the earliest two isolates in larger clusters and those in smaller clusters of only two isolates that did not appear to grow. Both the test and training datasets in this task contained very few individuals and further work would be required to determine whether it is possible to use these models to identify the earliest individuals with TB specifically in growing clusters. This may involve training classification models on larger datasets with more transmission clusters or by including the pairwise covariates between isolates, used previously to predict clustering of un-sequenced individuals with TB using demographic and clinical data14, to increase the information available to train these models.

Nevertheless, key characteristics were identified that were important features used by the classification models to discriminate between the earliest isolates in clusters and both isolates appearing later in clusters and non-clustered isolates. Previous work has identified disease characteristics correlated with Mtb transmission in multiple settings (e.g6,15), as well as developed complex multilevel models of individual risk prediction for TB16. These studies found evidence of patient and pathogen characteristics that were significantly associated with recent transmission, including TB lineage and age at diagnosis. In our analysis, the most important feature was found to be the patient demographic, with Canadian-born individuals more likely than foreign-born individuals to represent the earliest diagnosed hosts in transmission clusters. Pulmonary TB, previously reported to be associated with an increased TB transmission risk17,18, was also a key feature in tasks A–C of our analysis.

TB lineage was found to be an important feature and though balanced random forest models inherently evaluate the importance of variables independently by averaging across multiple decision trees built from subsets of the features, a much higher proportion of Canadian-born individuals harbored Euro-American lineage TB strains than foreign-born individuals (82% vs. 21%) and thus these features were likely to be correlated. Finally, we found patient age to have an impact on classification and patients over the age of 60 had a reduced likelihood of being the earliest isolates in cluster. While the prevalence of TB disease can be high in the elderly through reactivation of latent TB19, the decreased risk of onward transmission shown here in this group may be due to population-specific factors such as social mixing patterns.

In conclusion, we have used classification models to predict early TB isolates in clusters of recent transmission with respect to both host and disease characteristics. This work establishes a method to link patient-level correlates with predictive models to identify persons with TB that may have an increased risk of contributing to transmission cluster growth.

Methods

TB culture-positive individuals diagnosed in BC by the Public Health Laboratory (PHL) of the BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC) between 2005 and 2015 were included in this study, for which demographic and clinical data were collected as part of routine clinical investigation. Culture-positive individuals represent approximately 80% of all TB diagnoses in the province10. Sample preparation and DNA extraction was carried out at the British Columbia Public Health Laboratory (BCCDC PHL), as described previously10. WGS data was obtained from culture-positive individuals sampled between 2005 and 2014 whose TB isolate shared a MIRU-VNTR pattern with at least one other isolate, as per the PHL strategy during these years. In 2015, the strategy was changed to whole genome sequence isolates from all culture-positive individuals. Sequencing and bioinformatic analysis has been described elsewhere20.

Putative clusters representing recent transmission were identified by linking isolates with a maximum pairwise distance of 12 SNPs21. For the classification models, we partitioned the data into a training dataset of isolates collected between 2005 and 2011 and a test dataset of isolates collected between 2012 and 2013. Isolates collected in the last two years of the study were not included in the classification tasks as onward transmission may have occurred after the study period. However, isolates collected between 2005 and 2013 that clustered only with isolates collected in 2014 and 2015 were coded as clustered. Predictor variables were one-hot encoded, which represents categories as binary vectors22, and included demographic data (e.g., sex, age group, and demographics by country of birth) and clinical information (e.g., site of infection and antimicrobial susceptibility) (Table S1).

We trained models to carry out four different classification tasks using the 2005 to 2011 training dataset and tested model performance on the 2012 and 2013 test data, with a binary response variable in all instances. In the four classification tasks, the response variable coded as follows: (A) a value of 1 for the earliest two isolates in any transmission cluster and 0 for all non-clustered isolates, (B) a value of 1 for the earliest two isolates in any transmission cluster and 0 for all other isolates (all non-clustered isolates and all isolates with later collection dates in clusters), (C) a value of 1 for the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters of size greater than two and 0 for all non-clustered isolates and isolates in clusters of two, and (D) a value of 1 for the earliest two isolates in transmission clusters of size greater than two and 0 for isolates only in clusters of size two.

We tested the performance of multiple classification models, including machine learning (LightGBM, balanced random forest, and balanced bagging), deep learning (TabNet) models and balanced logistic regression, along with designing a neural network. For the best performing model, the feature importance and effect of the feature on the response variable was calculated to show whether each predictor variable has a positive or negative relationship. All models were run in Python 3.0.

Finally, we carried out two sensitivity analyses using the best performing model overall. Firstly, the training and test data were combined and randomly partitioned into new training and test datasets with an 80:20 ratio to determine whether the classification tasks were influenced by the partitioning of the data by date rather than the predictor variables, as well as controlling for any potential changes in demographics or treatment during the study period. Secondly, the response variable in the training data was randomly assigned to isolates, keeping the same proportion of 1s and 0s as in the real data, and all classification tasks re-run on the test dataset. This was to compare our results to the models when trained on training data with a randomly assigned response. All sensitivity analyses were repeated 100 times.

Data availability

The whole genome sequence data analyzed in the current study are available from the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) Project number PRJNA413593. The code to run the analysis can be found on GitHub (github.com/bensobkowiak/TBclusterClassification).

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023. (World Health Organization, 2023).

World Health Organization. The end strategy TB. End. TB Strateg 53, 1689–1699 (2017).

Fox, G. J., Barry, S. E., Britton, W. J. & Marks, G. B. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir J. 41, 140–156 (2013).

Chitwood, M. H. et al. The recent rapid expansion of multidrug resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ural lineage 4. 2 in the Republic of Moldova. Nat. Commun. 15, 1156 (2024).

Holt, K. E. et al. Frequent transmission of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing lineage and positive selection for EsxW Beijing variant in Vietnam. Nat. Genet. 50, 849–856 (2018).

Sobkowiak, B. et al. Bayesian reconstruction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission networks in a high incidence area over two decades in Malawi reveals associated risk factors and genomic variants. Microb. Genomics 6, 458 (2020).

Migliori, G. B. et al. Reducing tuberculosis transmission: a consensus document from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Eur. Respir J. 53, 56 (2019).

Althomsons, S. P. et al. Using Machine Learning Techniques and National Tuberculosis Surveillance Data to predict excess growth in genotyped tuberculosis clusters. Am. J. Epidemiol. 191, 1936–1943 (2022).

BC Centre for Disease Control. Tuberculosis Manual (2023).

Guthrie, J. L. et al. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in British Columbia, Canada: a 10-Year retrospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 66, 849–856 (2018).

Singh, M. et al. Evolution of machine learning in tuberculosis diagnosis: a review of Deep Learning-Based Medical Applications. Electron 11, (2022).

Smith, J. P. et al. Machine learning to predict bacteriologic confirmation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in infants and very young children. PLOS Digit. Heal 2, e0000249 (2023).

Romanowski, K. et al. Using whole genome sequencing to determine the timing of secondary tuberculosis in British Columbia, Canada. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50, 1052–1063 (2021).

Susvitasari, K. et al. Epidemiological cluster identification using multiple data sources: an approach using logistic regression. Microb. Genomics 9, 1–14 (2023).

Xu, Y. et al. High-resolution mapping of Tuberculosis transmission: whole genome sequencing and phylogenetic modelling of a cohort from Valencia Region, Spain. PLoS Med. 16, 1–20 (2019).

Gupta, R. K. et al. Discovery and validation of a personalized risk predictor for incident tuberculosis in low transmission settings. Nat. Med. 26, 1941–1949 (2020).

Heffernan, C. et al. Predicting pulmonary tuberculosis in immigrants: a retrospective cohort study. ERJ Open. Res. 4, 1–8 (2018).

Churchyard, G. et al. What we know about Tuberculosis Transmission: an overview. J. Infect. Dis. 216, S629–S635 (2017).

Caraux-Paz, P., Diamantis, S., de Wazières, B. & Gallien, S. Tuberculosis in the Elderly. J. Clin. Med. 10, 5888 (2021).

Sobkowiak, B., Romanowski, K., Sekirov, I., Gardy, J. L. & Johnston, J. C. Comparing Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission reconstruction models from whole genome sequence data. Epidemiol. Infect. 151, (2023).

Stimson, J. et al. Beyond the SNP threshold: identifying outbreak clusters using inferred transmissions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 587–603 (2019).

Ashenden, S. K., Bartosik, A., Agapow, P. M., Semenova, E. & Industry, S. Chapter 2—introduction to artificial intelligence and machine learning. in Ashenden Machine Learning, and Data Science in the Pharmaceutical K. B. T.-T. E. of A. I. 15–26 (Academic Press, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-820045-2.00003-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S., J.C.J., and C.C. conceived and designed the study, J.C.J. and I.S. acquired the data, O.G.G. performed the main analysis under the supervision of B.S. O.G.G., B.S., J.C.J., and C.C. interpreted the results, O.G.G. and B.S. prepared the draft with substantial input from J.C.J. and C.C. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

Ethics were obtained from the University of British Columbia (certificate H12-00910) and informed consent for participation in the study was not required, as determined by institutional REB review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gharamaleki, O.G., Colijn, C., Sekirov, I. et al. Early prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission clusters using supervised learning models. Sci Rep 14, 27652 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78247-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78247-z