Abstract

Antioxidant-rich diets serve as protective factors in preventing obesity. The composite dietary antioxidant index (CDAI) represents a novel, comprehensive metric for assessing the antioxidant capacity of diets. Our objective is to investigate the relationship between the CDAI and obesity prevalence among adults in the United States. Dietary and anthropometric information about adults aged 20 years and older were obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2018. The CDAI was derived from six dietary antioxidants. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) ≥ 30 kg/m2, and abdominal obesity as a waist circumference (WC, cm) ≥ 102 cm for men and ≥ 88 cm for women. The relationship between CDAI and obesity, including abdominal obesity, was analyzed using logistic regression and subgroup analyses. A total of 25,553 participants were analyzed. With higher tertiles of the CDAI, both obesity (41.28% vs. 38.62 vs. 35.09%, P < 0.001) and abdominal obesity (63.75% vs. 59.54 vs. 52.09%, P < 0.001) prevalence notably declined. Adjusting for multiple confounders, the CDAI was found to be independently linked to obesity (OR = 0.980, 95%CI = 0.971–0.989, P < 0.001) and abdominal obesity (OR = 0.972, 95%CI = 0.963–0.982, P < 0.001) risks. Subgroup analyses revealed a stronger relationship between CDAI and obesity in non-hypertensive individuals and a more significant association with abdominal obesity in women and those without hypertension. Our findings reveal a negative relationship between CDAI levels and both general and abdominal obesity. Additional extensive research is necessary to investigate CDAI’s contribution to obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity and its global prevalence are increasingly becoming a significant worldwide risk1. Extensive evidence to date shows that excess body fat is associated with increased markers of oxidative stress2. Oxidative stress plays a crucial role in the onset and progression of obesity and related diseases3. Under physiological conditions, antioxidants delicately control reactive oxygen species levels, sourced both internally and externally4. Insufficient antioxidant consumption can lead to an excess of reactive oxygen species, causing oxidative stress and subsequently exacerbating the inflammatory state associated with obesity3,5,6. The CDAI stands as a robust and credible nutritional instrument designed to evaluate the comprehensive antioxidant profile of one’s diet. This index aggregates the effects of six key dietary antioxidants: vitamins A, C, and E, alongside carotenoids, selenium, and zinc, offering a succinct measure of dietary antioxidant capacity7,8,9. Prior research has elucidated an inverse correlation between CDAI levels and the risk of various diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, cancer, osteoporosis, and depression10,11,12,13,14. However, whether the CDAI can effectively identify high-risk populations for obesity remains uncertain. Furthermore, as a novel dietary index, it is yet to be determined if it could assess the dietary antioxidant capacity of obese individuals.

Utilizing data from the NHANES database, this study aims to meticulously explore the potential link between CDAI and both general and abdominal obesity risk through a detailed cross-sectional analysis.

Materials and methods

Data source

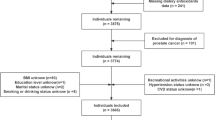

This study utilized data from the NHANES, an extensive survey executed by the National Center for Health Statistics within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES implemented a meticulously designed, randomized, stratified, multi-stage survey approach to achieve a representative sample of the national population. Participants were subjected to comprehensive physical examinations, alongside health and nutrition questionnaires, and laboratory evaluations15,16. The study protocol of NHANES was sanctioned by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. In-depth methodology and data from this investigation are further available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/. This study compiled data from the NHANES cycles spanning 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018, including 59,842 participants. We excluded those who were under 20 years old, pregnant, or did not provide complete dietary questionnaires or anthropometric data (including BMI and WC), resulting in a total of 25,553 eligible participants.

Exposure and outcome definitions

In the NHANES database, the intake of food and nutrients for each participant was documented through a 24-hour dietary recall interview. The initial recall was carried out face-to-face, followed by a second recall conducted over telephone 3 to 10 days later. The CDAI, representing each participant’s total dietary antioxidant intake, was calculated using the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) data7,8. Based on the questionnaire interview, we determined the antioxidant components, including vitamins A, C, E, carotenoids, zinc, and selenium. Dietary antioxidant carotenoids were determined by adding the intake of α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene17. The normalization of these six antioxidants was conducted by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. Following this, the CDAI was calculated based on the sum of these normalized values. The detailed calculation formula is as follows: \({\text{CDAI}}:={\sum}_{\text{i}=1}^{6}\left(\frac{{\text{Individual\,Intake}}-{\text{Mean}}}{{\text{standard deviation}}}\right).\) On other hand, obesity is defined as a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, and particularly abdominal obesity as a WC ≥ 102 cm for men and ≥ 88 cm for women.

Covariate definitions

Demographic information such as age (years), gender (female/male), and race (Mexican American/Non-Hispanic Black/Non-Hispanic White/Other Hispanic/Other Race), along with a range of potential covariates including annual household income (below or above $20,000), education level (above high school or not), physical activity (moderate or not), smoking status (smoker/non-smoker), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), cardiovascular disease (yes/no), glycohemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, in mmHg), and total energy intake were gathered. Smokers were categorized as either current or past smokers. Self-reported cases of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease were also recorded. Cardiovascular disease was identified through self-reports of heart attack, stroke, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or angina. Detailed methods for measuring all variables are available in the NHANES database.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis followed the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, employing a complex multistage cluster survey design and incorporating weights from six cycles. Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard errors (SE), and categorical variables as percentages (SE). Differences in continuous and categorical variables between groups were assessed using the weighted Student’s t-test and chi-squared test, respectively. The relationship between CDAI (continuous/quartile) and obesity, abdominal obesity, BMI, and WC was examined through logistic and linear regression models. Three models were applied: Model 1 without adjustments; Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, and race; and Model 3 adjusted for age, gender, race, annual household income, education level, physical activity, smokers, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, HbA1c, SBP, DBP, and total energy intake. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on age (< 60/≥60 years), gender (female/male), race (white/non-white), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), and cardiovascular disease (yes/no). Additionally, the relationship between CDAI and obesity, abdominal obesity, BMI, and WC was further explored based on the Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) analysis. All statistical analyses were carried out using the Empower software (http://www.empowerstats.com) and the R software (http://www.R-project.org), with a two-side P value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

This study ultimately encompassed 25,553 participants who met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). The mean age was 48.07 years, with males making up 48.08% of the participants. For lifestyles and risk factors associated with obesity, the prevalence rates were observed as follows: 13.18% among individuals with an annual household income below $20,000; 62.59% in those with an education level above high school; 42.32% for those engaging in moderate physical activity; 44.06% among smokers; 32.26% for individuals with hypertension; 9.78% for those diagnosed with diabetes; and 8.38% for individuals with cardiovascular disease. The population’s average BMI was 29.11 kg/m2, WC was 99.85 cm, HbA1c was 5.63%, SBP was 121.79 mmHg, DBP was 70.55 mmHg, total energy was 2092.82 kcal, carotenoids was 9774.35 mcg, vitamin A was 648.88 mg, vitamin E was 9.50 mg, vitamin C was 81.31 mg, selenium was 113.84 mcg, zinc was 11.43 mg, and CDAI was 0.91. Among participants, 38.11% were classified as obesity, and 58.05% exhibited abdominal obesity.

Clinical features of the participants according to the tertiles of CDAI

Participants were divided into three groups according to their CDAI levels (Table 2). As CDAI levels increased from tertile 1 to tertile 3, there was a significant decrease in age, the proportion of female, annual household income below $20,000, smokers, and those with hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, BMI, WC, HbA1c, and SBP (P < 0.05). Conversely, education level above high school, moderate physical activity, DBP, total energy, carotenoids, vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin C, selenium, and zinc escalated, along with significant race distribution observed (P < 0.001). Notably, the prevalence of general obesity (41.28% vs. 38.62 vs. 35.09%, P < 0.001) and abdominal obesity (63.75% vs. 59.54 vs. 52.09%, P < 0.001) decreased markedly. Additionally, compared to the general population, individuals with overall obesity and abdominal obesity exhibit lower levels of CDAI (P < 0.001) (Attachment 1).

Associations between CDAI and general obesity, abdominal obesity, BMI, and WC

Our research indicates a significant inverse relationship between CDAI and the risk of obesity. This negative association persists across various models: Model 1 (OR = 0.971, 95%CI = 0.965–0.977, P < 0.001), Model 2 (OR = 0.983, 95%CI = 0.977–0.990, P < 0.001), and Model 3 (OR = 0.980, 95%CI = 0.971–0.989, P < 0.001). Specifically, individuals in the highest tertile of CDAI were found to have a 14.0% reduced risk of obesity in the fully adjusted model, compared to those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.860, 95%CI = 0.785–0.942, P = 0.001) (Table 3). Moreover, a significant inverse correlation between CDAI and abdominal obesity was identified after adjusting for potential confounders (OR = 0.972, 95%CI = 0.963–0.982, P < 0.001). When analyzing CDAI into tertiles, it was evident that individuals in higher CDAI tertile presented a lower prevalence of abdominal obesity than those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.818, 95%CI = 0.745–0.898, P < 0.001) (Table 3). Furthermore, linear regression analyses, with BMI and WC as dependent variables, also revealed a significant negative relationship between CDAI and both BMI (β=-0.057, 95%CI=-0.083–0.031, P < 0.001) and WC (β=-0.185, 95%CI=-0.246–0.124, P < 0.001) (Table 4). Due to inappropriate dietary habits commonly followed by obese individuals, we further assessed whether general and abdominal obesity populations, compared to normal populations, have a higher risk of exhibiting low CDAI levels (Table 5). The results indicate that individuals with general and abdominal obesity indeed have a higher risk of low CDAI levels (P < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the consistency of the CDAI-obesity and CDAI-abdominal obesity associations across various demographics (Figs. 1 and 2). The results show that age, gender, race, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease presence do not significantly modify the CDAI-obesity relationship (P for interaction > 0.05). However, a significant interaction between hypertension and the CDAI-obesity link was observed, with a stronger correlation in non-hypertensive individuals (P for interaction < 0.05). On other hand, these factors do not significantly influence the CDAI-abdominal obesity association (P for interaction < 0.05), except for a notable interaction between gender, hypertension, and the CDAI-abdominal obesity relationship, indicating a stronger correlation in non-hypertensive females compared to hypertensive males (P for interaction < 0.05). Lastly, the RCS results revealed a negative relationship between the CDAI and the risk of obesity and abdominal obesity, with no significant threshold effect detected (P for nonlinear = 0.466 and 0.403) (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Our population-based study examined the association of CDAI with obesity and abdominal obesity. The present study found that obesity was prevalent in approximately 38.11% among U.S. adults, while abdominal obesity was found in 58.05% of the adult population. This result is broadly consistent with previous estimates of the prevalence of obesity and abdominal obesity in the US population18. We observed an inverse relationship between CDAI and both general and abdominal obesity, suggesting that CDAI might function as a protective factor against the inflammatory conditions associated with obesity.

Oxidative stress plays a key role in obesity’s pathophysiology by affecting mitochondrial function, altering inflammation mediators linked to adipocyte size and number, driving lipogenesis, encouraging preadipocyte differentiation into mature cells, and influencing hypothalamic neurons that regulate appetite and energy balance3. Dietary intake of vitamins A, C, and E, alongside carotenoids, selenium, and zinc, play crucial roles in modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Vitamin A, alongside carotenoids, is pivotal in maintaining immune function, while also modulating adipogenesis, the process by which preadipocytes mature into adipocytes19,20. Vitamin C, beyond its well-documented role in immune enhancement, contributes to the synthesis of collagen and the lipid metabolism21. Vitamin E, recognized for its antioxidant capacity, is involved in preventing lipid peroxidation within cell membranes, thereby protecting cells from oxidative damage22. Selenium and zinc are trace elements essential for the proper functioning of various antioxidant enzymes. Selenium’s role in the activity of glutathione peroxidase, an enzyme that reduces peroxides, highlights its significance in mitigating oxidative damage23. Zinc, on the other hand, enhances the activity of antioxidant proteins and enzymes, including glutathione and catalase24. Thus, it can be definitively stated that dietary antioxidants, through their bioactive compounds, generate a synergistic action that mitigates oxidative stress and delivers antioxidant advantages, consequently diminishing the risk of obesity11,25. The CDAI, serving as an innovative antioxidant index, effectively encapsulates the cumulative impact of these dietary antioxidants, evaluating the genuine antioxidant efficacy from a clinical standpoint. Nevertheless, it is imperative to note that the precise molecular mechanisms remain elusive, necessitating further investigation.

This study leveraged a sample representative of the ethnic diversity found within the US adult population, however it’s important to acknowledge its limitations. The cross-sectional approach restricts our capacity to establish causality between CDAI and the risk of obesity, further longitudinal studies and clinical trials are indispensable. Moreover, the exclusion of potential confounding factors such as metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease may have impacted our results. Additionally, although our study indicates a negative correlation between CDAI and obesity prevalence, future research is needed to further define the threshold for evaluating sufficient antioxidant properties in diets. Finally, considering this study’s focus on the US adult population, extending its conclusion to other demographic groups requires more in-depth analysis.

Conclusion

An inverse relationship was observed between CDAI and both general and abdominal obesity. Maintaining high CDAI levels might act as a protective factor against obesity-related inflammatory conditions. However, further studies are required to validate our findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the NHANES database (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/).

References

Haslam, D. W. & James, W. P. Obesity. Lancet 366(9492), 1197–1209. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67483-1 (2005).

Bonomini, F. Antioxidants and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(16), 12832. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612832 (2023).

Pérez-Torres, I. et al. Oxidative stress, Plant Natural Antioxidants, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(4), 1786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041786 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Role of ROS and Nutritional antioxidants in Human diseases. Front. Physiol. 9, 477. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.00477 (2018).

Luu, H. N. et al. Are dietary antioxidant intake indices correlated to oxidative stress and inflammatory marker levels? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22(11), 951–959. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2014.6212 (2015).

Nani, A., Murtaza, B., Sayed Khan, A., Khan, N. A. & Hichami, A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of Polyphenols contained in Mediterranean Diet in obesity: Molecular mechanisms. Molecules. 26(4), 985. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26040985 (2021).

Wright, M. E. et al. Development of a comprehensive dietary antioxidant index and application to lung cancer risk in a cohort of male smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160(1), 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh173 (2004).

Wu, D. et al. Association between composite dietary antioxidant index and handgrip strength in American adults: Data from national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES, 2011–2014). Front. Nutr. 10, 1147869. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1147869 (2023).

Maugeri, A. et al. Dietary antioxidant intake decreases carotid intima media thickness in women but not in men: a cross-sectional assessment in the Kardiovize study. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 131, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.12.018 (2019).

Wu, M., Si, J., Liu, Y., Kang, L. & Xu, B. Association between composite dietary antioxidant index and hypertension: insights from NHANES. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 45(1), 2233712. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641963.2023.2233712 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Composite dietary antioxidant index was negatively associated with the prevalence of diabetes independent of cardiovascular diseases. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01150-6 (2023).

Yu, Y. C. et al. Composite dietary antioxidant index and the risk of colorectal cancer: findings from the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Int. J. Cancer. 150(10), 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33925 (2022).

Liu, J., Tang, Y., Peng, B., Tian, C. & Geng, B. Bone mineral density is associated with composite dietary antioxidant index among US adults: results from NHANES. Osteoporos. Int. 34(12), 2101–2110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06901-9 (2023).

Zhao, L. et al. Non-linear association between composite dietary antioxidant index and depression. Front. Public. Health 10, 988727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988727 (2022).

Paulose-Ram, R., Graber, J. E., Woodwell, D. & Ahluwalia, N. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2021–2022: Adapting data collection in a COVID-19 environment. Am. J. Public. Health. 111(12), 2149–2156. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306517 (2021).

Ahluwalia, N., Dwyer, J., Terry, A., Moshfegh, A. & Johnson, C. Update on NHANES dietary data: Focus on collection, release, analytical considerations, and uses to inform Public Policy. Adv. Nutr. 7(1), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.009258 (2016).

Qiu, Z. et al. Associations of serum carotenoids with risk of cardiovascular mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from NHANES. Diabetes Care 45(6), 1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-2371 (2022).

Cheang, I. et al. Inverse association between blood ethylene oxide levels and obesity in the general population: NHANES 2013–2016. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13, 926971. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.926971 (2022).

Amimo, J. O. et al. Immune impairment associated with vitamin A deficiency: Insights from clinical studies and animal model research. Nutrients 14(23), 5038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235038 (2022).

Gomes, C. C., Passos, T. S. & Morais, A. H. A. Vitamin A status improvement in obesity: findings and perspectives using encapsulation techniques. Nutrients 13(6), 1921. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061921 (2021).

Lee, S. W. et al. Vitamin C Deficiency inhibits nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression through Impaired de Novo Lipogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 191(9), 1550–1563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.05.020 (2021).

Saito, Y. Lipid peroxidation products as a mediator of toxicity and adaptive response - the regulatory role of selenoprotein and vitamin E. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 703, 108840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2021.108840 (2021).

No authors listed. Incorporation of selenium into glutathione peroxidase. Nutr. Rev. 45(11), 344–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1987.tb00988.x (1987).

Jarosz, M., Olbert, M., Wyszogrodzka, G., Młyniec, K. & Librowski, T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of zinc. Zinc-dependent NF-κB signaling. Inflammopharmacology 25(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-017-0309-4 (2017).

Schiffrin, E. L. Antioxidants in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Mol. Interv. 10(6), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1124/mi.10.6.4 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge all participants of this study and the support provided by the Jiangsu University.

Funding

This study was supported by the Suzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (STL2021006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and Q.W. wrote the main manuscript text. F.T. prepared figures and tables. S.Z. reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm). All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Wang, Q., Tang, F. et al. Composite dietary antioxidant index and obesity among U.S. adults in NHANES 2007–2018. Sci Rep 14, 28102 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78852-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78852-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between age at first birth and cognitive function in women 60 years and older: the 2011–2014 cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

The association between a newly proposed gut microbiota dietary index and obesity among U.S. adults: a cross-sectional analysis based on NHANES 1999–2020

Nutrition Journal (2025)

-

The association between composite dietary antioxidant index and sarcopenic obesity

Nutrition & Metabolism (2025)

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index-mediated association of composite dietary antioxidant index with obesity in children and adolescents: based on NHANES 2011–2018

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

The mediating role of BMI in the association between composite dietary antioxidant index and infertility in women: a nationwide population-based study

BMC Women's Health (2025)