Abstract

This paper considers uplink and downlink transmissions in a network with radio frequency-powered Internet of Things sensing devices. Unlike prior works, for uplinks, these devices use framed slotted Aloha for channel access. Another key distinction is that it considers uplinks and downlinks scheduling over multiple time slots using only causal information. As a result, the energy level of devices is coupled across time slots, where downlink transmissions in a time slot affect their energy and data transfers in future time slots. To this end, this paper proposes the first learning approach that allows a hybrid access point to optimize its power allocation for downlinks and frame size used for uplinks. Similarly, devices learn to optimize (1) their transmission probability and data slot in each uplink frame, and (2) power split ratio, which determines their harvested energy and data rate. The results show our learning approach achieved an average sum rate that is higher than non-learning approaches that employed Aloha, time division multiple access, and round-robin to schedule downlinks or/and uplinks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Future Internet of Things (IoT) networks will consist of low-power devices that sense their environment and transmit data to a gateway1. The gateway may then use the data from devices to train a neural network2. Further, a gateway may instruct devices to carry out sensing task(s)3 or control an actuator. In these scenarios, channel access is a key issue in order to facilitate uplinks and downlinks transmissions over the same channel. Moreover, devices may experience collision when they upload their data to a gateway. Hence, a key issue is to determine when a device accesses a channel given unknown number of contending devices.

Another key issue is managing the available energy of devices, where they rely on a hybrid access point (HAP) for energy. Briefly, these devices are charged via far-field wireless charging; see4 for an example prototype. Specifically, radio frequency (RF)-charging takes advantage of the existing spectrum that is used for data transmissions to also deliver energy. This fact has led to technologies such as Simultaneous Wireless Information and Power Transfer (SWIPT)5, where devices are able to receive both information and energy simultaneously. In this respect, SWIPT supports time switching6 and power splitting7. Specifically, with a power splitter, a receiver divides the power of a received signal between its energy harvester and data decoder. This division of power is a variable to be optimized by the receiver. In contrast, time switching has two phases. In the first phase, the HAP charges devices. After that, in the following phase, devices are allocated a given time slot to transmit data. The main variable to be optimized is the time allocated to each device for uplink transmission as well as the charging phase duration used by the HAP8.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper considers joint optimization of uplink and downlink data communications in a RF-energy harvesting IoT network. Further, it takes advantage of non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA)9 for downlink transmissions, where a HAP uses superposition coding to transfer information to all devices. For uplinks, past works pre-assign time slots or sub-carriers for each user, which will cause slot wastage when users run out of battery. Considering that users transmit opportunistically based on their energy level, this paper adopts random channel access, framed slotted Aloha, to avoid wasting pre-assigned time slots. Moreover, the HAP uses Successive Interference Cancellation (SIC) to decode concurrent transmissions from devices. Note that NOMA allows for higher spectrum efficiency, and thus it is a key technology in future networks10. In terms of energy delivery, devices adopt power splitting. Note that there is a trade-off between the harvested energy and information decoding, which affects uplink and downlink rates, respectively. Concretely, less harvested energy results in less uplink transmission power which may impair the uplink rate. Accordingly, less power directed to information decoding impairs the downlink rate. Thus, a key problem is to determine a suitable power split ratio that maximizes the amount of harvested energy and sum rate during downlink transmissions. Lastly, the HAP employs Frame Slotted Aloha (FSA) for uplink transmissions, meaning devices are not allocated a fixed time slot. A key advantage of FSA is that an HAP does not have to allocate a fixed time slot to devices with insufficient energy to transmit. In this respect, the HAP can optimize its frame size in accordance with the number of transmitting devices.

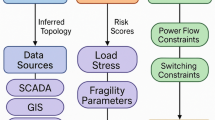

Figure 1 shows the downlink and energy delivery process in an example IoT network with RF-charging devices. During downlink, the HAP simultaneously transmits data and RF energy to all devices, where the HAP superposes its transmission to both devices. For ease of exposition, assume that the HAP uses 2 W and 1 W when it transmits to \(U_{1}\) and \(U_{2}\), respectively. Further, assume the channel power gain between the HAP and devices equals one. Lastly, each device has a power split ratio of \(\theta\). As shown in Fig. 1a, device \(U_{2}\) adopts a power split ratio of \(\theta =0.8\). Thus, a total of \(0.8\times 3=2.4\) W is sent to its information decoder. The remaining 20% of its received power is sent to its energy harvester. Device \(U_{1}\) adopts a power split ratio of \(\theta =0.5\). This means device \(U_{1}\) sends 1.5 W to its information decoder and the other 1.5 W to its energy harvester. By using SIC decoding, device \(U_{1}\) and \(U_{2}\) are able to iteratively decode the signal.

Figure 1b demonstrates downlink and uplink transmissions for two time frames. The HAP first superposes all data together to all devices during the downlink period. After that, devices use their harvested energy to transmit during the uplink period. To do so, in frame \(t=1\), device \(U_{2}\) selects the first data slot while device \(U_{1}\) selects the third data slot. In this case, both data transmissions are successful. However, in frame \(t=2\), devices selected the same data slot. In this case, due to SIC, their transmission is also successful.

There are a number of challenges. First, the uplink transmit power of devices is a function of their harvested energy in prior time slots or downlinks from the HAP11. Second, the energy level of devices depends on past channel gains, power split ratio and transmissions. Third, information is causal, meaning both HAP and devices know the current and past channel gains information only. Consequently, devices are unable to predict their future channel states or future energy arrivals, which undoubtedly increases the difficulty for them in making transmission decisions. Specifically, devices do not know whether they should reserve their precious energy for future slots with better channel gains or should transmit immediately. Fourth, the HAP is unaware of the number of contending devices and the energy level of devices. In practice, obtaining this information involves signaling, which consumes the precious harvested energy of devices. To address these challenges, this paper utilize Q-learning based approach to learn the system energy arrivals and channel condition variation. Henceforth, this paper makes the following contributions:

-

It studies an IoT network that uses NOMA and FSA. It addresses a novel problem that aims to jointly maximize uplink and downlink sum rates over multiple time frames using only causal information. To the best of our knowledge, no prior works have considered a system that employs FSA for uplinks nor the same problem. Further, they have not addressed the said challenges jointly; see “Related works” Section for details.

-

It shows how the uplink and downlink transmission problem can be modeled as Markov Decision Process (MDP). Advantageously, the MDP is model-free, meaning it does not require statistics of an environment beforehand. This means it only needs to observe the current system state, and then executes an action as per a learned policy. In this respect, to determine the optimal policy, this paper outlines Multi-Q; it is the first reinforcement learning approach for the problem at hand and system. It yields a communication policy for different channel conditions, where for each system state, it determines the HAP’s transmit power allocation and frame size. Further, it trains devices to use the correct power split ratio that maximizes their harvested energy and downlink sum rate. Lastly, devices use Multi-Q to determine a slot in a given frame and transmission probability.

-

It presents the first study of Multi-Q. The simulation results show that Multi-Q achieves an average sum rate of 44 b/s/Hz which is 6× that of Aloha, 2.3× that of time division multiple access (TDMA), and 30% more than round-robin.

Related works

In general, past works that consider downlink and uplink communications in RF-charging networks optimize over one frame; i.e., they do not consider energy evolution and future channel gains of devices. These works mainly consider two different kinds of frame structures. One frame structure, see e.g.,12,13,14, is where the HAP first transfers energy to all users. After that, each user is assigned a distinct time slot during downlink. The HAP then sequentially sends data to each user. Works such as13 consider users that not only harvest energy during downlinks via a time switching strategy, but they also harvest energy whenever there are uplink transmissions. The work in14,15,16,17 considers users who harvest energy when the HAP transmits information to other users. During their assigned slot, a user employs power splitting to harvest energy. Lastly, in reference15, the authors also consider an interfering source. Users harvest energy from both their HAP and interfering signals via power splitting.

Some works consider an HAP that simultaneously sends data to all users using NOMA or multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) technologies. Example works include18,19, where the HAP uses a MIMO system. Qin et al.18 assume a fixed power split ratio and time division duplex. In a subsequent work, i.e.,19, they optimize the power split ratio for each user to maximize system throughput. References20,21,22 consider NOMA for downlink. Li et al.20 employ NOMA in both single-input single-output (SISO) and MIMO models. In the case of SISO-NOMA, the authors optimize the power split ratio for each user. In the case of MIMO-NOMA, except for determining the power split ratio at devices, the authors also optimize the time allocation for downlink and uplink duration to enhance sum rate. Baidas et al.21 jointly optimize time switching and power allocation in a single-cell NOMA system to maximize the sum rate of uplink and downlink while ensuring quality of service requirements of users. In a subsequent work22, Baidas et al. further consider a NOMA system with clusters of users. The aim is still to maximize the sum rate of uplink and downlink while ensuring quality of service requirements are met. The authors jointly optimize time switching and power allocation of each cluster, and its sub-carrier assignment.

Another research direction is to adopt different sub-carriers for uplink and downlink communications. For example, Rezvani et al.23 consider a multi-user orthogonal frequency division multiple access (OFDMA)-based system with one base station and one local access point, where the base station can offload data to a local access point. The aim is to maximize uplink throughput subject to a minimum required downlink data rate of each user. To do this, the authors optimize power split ratio at users, joint sub-carrier allocation, and transmit power allocation. Na et al.24 categorize sub-carriers into two groups for information decoding and energy harvesting, respectively. Xiong et al.25 aim to jointly optimize the downlink and uplink energy efficiency and prolong system lifetime in a Time Division Duplex (TDD) Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) system with a power split strategy.

Table 1 highlights the novelties of our work. Briefly, many works have employed convex optimization and solves a deterministic problem, i.e., they do not consider imperfect or stochastic channel gains. For example, the work in12,13,17,18,19,20 casts or transforms their proposed maximization problem into a concave one and use convex program. Some other works also consider Mixed-Integer Non-Linear Program (MINLP), e.g., reference21,22,23. To date, only the work in26 has considered multiple time slots with imperfect channel gains. Lastly, in26, transmissions and receptions are carried out using TDD. A key innovation is the use of high and low frequency bands for energy and data transmissions. Further, access point optimizes its beamforming weight according to channel condition and energy at devices.

Our work fills a number of gaps. First, unlike past works that assume non-causal information and perfect channel information, we consider the causal case, meaning the HAP and devices make decision without requiring future channel gains information. Second, these works do not consider random channel access. Specifically, they consider pre-assigned time slots or sub-carriers, see12,13,14,23,24,25. Thus, there will be wasted slots due to device energy outage which will impair transmission efficiency and system throughput. In contrast, for practical reasons, our devices employ slotted Aloha to transmit to a SIC-capable HAP. Slotted Aloha is a random channel access method that enables flexible transmissions based on battery states. With SIC enabled, collisions can be resolved to further improve system throughput. Third, they optimize resources over one slot. Specifically, except for Yao et al.26, they do not consider energy evolution and future channel gains of devices nor the coupling between energy level across time slots. We note that Yao et al.26 consider a known probability distribution of channel and data arrivals. Further, they do not consider random channel access and do not aim to maximize system throughput.

System model

A HAP serves N energy harvesting devices; each device is denoted as \(U_{i}\), where \(i\in \{1,2,\ldots , N\}\). The HAP uses NOMA in the downlink and devices employ FSA for uplinks, where devices select one of M slots to transmit their packet. Time is divided into frames and indexed by t. At the beginning of each frame, the HAP will send pilot symbols for channel estimation. After that, each frame is divided into a downlink and uplink period, which respectively has length \(\tau _d\) and \(\tau _{u}\). During the downlink period, devices employ power splitting5 to split received power into two parts, namely energy harvesting and information decoding. After that, there are M time slots for uplinks.

Channel model

We consider Rayleigh block fading channels27. The channel remains the same within one frame but varies across frames. Let \(d_{i}\) be the distance between \(U_{i}\) and the HAP, n denotes the path loss exponent, \(\lambda\) denotes an exponential random variable with unity mean, and \(h_{i}^{t}\) denotes the channel gain between user \(U_{i}\) and the HAP in time frame t. The channel power gain \(h_{i}\) is defined as \(h_{i}^{t}=\lambda {d_{i}}^{-n}\)28.

From a practical point of view, we consider casual channel information. That means HAP and devices make transmission decisions only with the current and past channel gains information. Consequently, even Rayleigh fading drives the channel state variation, neither HAP nor devices are aware that state transitions are driven by a Rayleigh distribution. Concretely, for a given time slot, devices cannot predict any future channel states or energy arrivals. Hence it is hard for a device to decide whether it should use up its energy to transmit or it should reserve its energy for future slots with a better channel state.

Downlink

During each downlink period, the HAP superposed all signals together and transmit the resulting composite signal to all users10. The HAP has a maximum transmit power of P, and the power allocated for user \(U_{i}\) at time frame t is \(p_{i}^{t}\), where \(0 \le p_{i}^{t} \le P\). Moreover, the sum of transmit power to each user must not exceed P; formally, \(\sum _{i=1}^{N}{p_{i}^{t} \le P}\). Further, each user \(U_{i}\) divides its received signal into two signals with a split ratio of \(\theta\), where \(0\le \theta \le 1\). Let \(\theta\) denote the fraction of received power devoted to information decoding. The remaining \(1-\theta\) fraction of the received power is sent to an energy harvester.

Downlink information decoding

Users have a SIC decoder29. Briefly, each user \(U_{i}\) starts its SIC decoding from the strongest signal by treating other signals as interference. After having successfully decoded the strongest signal, user \(U_{i}\) will subtract the decoded signal from the composite signal and proceeds to decode the next strongest signal. This continues until user \(U_{i}\) decodes its signal.

An example is shown in Fig. 2, where the HAP transmits with more power to user \(U_{2}\) than \(U_{1}\). User \(U_{1}\) decodes the signal designated for \(U_{2}\) first and subtracts it from its received composite signal. After removing the signal from \(U_{2}\), user \(U_{1}\) decodes its signal. As for user \(U_{2}\), it directly decodes its signal by treating the signal of user \(U_{1}\) as interference.

Let \(n_0\) denote the noise power and W denote the bandwidth. The achievable downlink rate for user \(U_{i}\) at time frame t is

Energy harvesting

Each user is equipped with an RF-energy harvester, e.g., P2110B RF-energy harvester30. Let \(\check{P}_{i}^{t}\) denote the received power at user \(U_{i}\). It is calculated as \(\check{P}_{i}^{t}=h_{i}^{t}P\). It transfers \((1-\theta ) \check{P}_{i}^{t}\) amount of power to its energy harvester. Note that the RF-energy conversion process is non-linear, which is a function of the received power. We consider a practical non-linear energy harvesting model31. Denote the energy conversion efficiency as \(\eta\), which has range [0, 1]. It is calculated as

where \(\chi _{i}^{t}=(\Psi _{i}^{t}-M\Omega )/(1-\Omega )\), \(\Omega = 1/(1+e^{ab})\), \(\Psi _{i}^{t}= M/(1+e^{-a(\check{P}_{i}^{t}-b)})\). Here, M is the maximum harvested power, and the value of a and b is as per a harvester’s circuit.

Denote \(\xi _{i}^{t}\) as the harvested energy of \(U_{i}\) in time frame t. Formally, the harvested energy is

Let \(\upsilon _{i}^{t}\) denote the amount of energy consumed by \(U_{i}\) for uplink transmission in frame t. Thus, each device has energy level \(E_{i}^{t}\) that evolves as per \(E^{t}_{i}=E^{t-1}_{i} + \xi _{i}^{t} -\upsilon _{i}^{t}\). Moreover, each user has a battery capacity of \(B_{max}\). This means if a device’s battery is full, any subsequent energy arrival is lost. Consequently, the energy level of user \(U_{i}\) evolves as per

Uplink

Users use FSA for uplink transmissions. This means the HAP does not allocate a fixed time slot to a device. Concretely, users will randomly select a time slot to access the channel when it has sufficient energy. In contrast, if the time slot is pre-assigned to each device by the HAP, time slots may be wasted if any device experiences an energy outage. Moreover, if the HAP pre-assigns time slots based on the energy level of each device, it requires the HAP to gather energy level information. Consequently, it requires the HAP to poll devices, which is not practical when there are many devices. Further, this also wastes the precious energy of devices. In contrast, FSA provides energy harvesting nodes with more flexibility to report data. This means devices can transmit more flexibly based on their energy level to avoid wasting slots. Transmission efficiency will be improved since fewer time slots are wasted due to battery outages. For this reason, we adopt FSA, and have the HAP adjusts the frame size used for uplink transmissions based on system states.

The HAP has SIC capability29, meaning it is able to decode multiple transmissions within a time slot. Let \(\varepsilon _0\) be the minimum energy used to transmit one packet. Thus, user \(U_{i}\) will only transmit when its battery level \(E_{i}^{t}\) exceeds \(\varepsilon _0\). Further, user \(U_{i}\) will use up all its available energy to transmit. We denote the uplink transmission power of \(U_{i}\) as \(y_{i}^{t}\). Then we calculate \(y_{i}^{t}\) as per \(y_{i}^{t}=\frac{E_{i}^{t}}{\tau _{up}/M}\), where M is the frame size. For each user \(U_{i}\), we record the number of transmissions in its selected slot as \(\Phi _{i}^{t}\). Therefore, the condition \(\Phi _{i}^{t} \le 1\) represents the fact that there are no other users transmitting in the same slot with user \(U_{i}\). Otherwise, the condition \(\Phi _{i}^{t}>1\) means there are users transmitting in the same slot with user \(U_{i}\). Consequently, the achievable uplink transmission rate for user \(U_{i}\) is defined as

An example of downlink and uplink transmission. There are two users and user \(U_{2}\) has poorer channel condition and a higher transmit power. The left side of the figure shows downlink transmission, where the HAP transmits energy and data to users. Users use power splitting to harvest energy. The right side of the figure shows users transmit data via FSA in the uplink. The HAP uses SIC to decode information.

Problem

Given the aforementioned system, the goal is to optimize both uplink and downlink sum rate, i.e., summation of downlink rate \(\check{R_{i}^{t}}\) and uplink rate \(\hat{R_{i}^{t}}\). Here, the uplink rate \(\hat{R_{i}^{t}}\) and downlink rate \(\check{R_{i}^{t}}\) are calculated as per Eqs. (1) and (5), respectively. Moreover, in each time frame t, a policy \(\pi\) returns all the parameters used in Eqs. (1) and (5). Specifically, a policy \(\pi\) returns the downlink transmission power \(p_{i}^{t}\), uplink transmission probability \(\rho _{i}^{t}\), uplink slot selection \(\delta _{i}^{t}\), frame size M, and power split ratio \(\theta\). Formally, a policy \(\pi\) is defined as \(\pi =[ p_{i}^{t}, \rho _{i}^{t}, \delta _{i}^{t}, M, \theta ]\). Thus, the joint sum rate is calculated as per Eq. (6):

Define \(\Pi =[\pi _{1}, \pi _{2},\ldots ]\) as a collection of available policies. Our problem is to find the optimal policy \(\pi ^{*} \in \Pi\) that maximizes the following long-term cumulative joint uplink and downlink reward:

To solve the optimal policy \(\pi ^{*}\), we need to determine the following quantities: (1) Downlink transmission power \(p_{i}^{t}\) of the HAP for each device \(U_{i}\) in frame t, (2) Uplink transmission probability \(\rho _{i}^{t}\) of device \(U_{i}\), (3) Uplink slot selected by device \(U_{i}\), namely \(\delta _{i}^{t}\) in each frame, (4) Frame size M, and (5) Power split ratio \(\theta\) of all devices.

MDP model and Q-leaning approach

We first show how the uplink and downlink process can be modeled as an MDP32. After that, we introduce conventional Q-learning33. Note that Q-learning is a sequential decision approach that learns the optimal policy without using non-causal information. Advantageously, it is model-free, meaning they are able to learn the optimal policy by only observing system states over time. Specifically, Q-learning allows the system to learn the fact that channel state transitions are driven by Rayleigh distribution with only causal channel information. Then we introduce stateless Q-learning34. Finally, we outline Multi-Q and show how it allows a HAP and users to use conventional Q-learning to learn the optimal policy that determines downlink power allocation, uplink transmission probability and slot selection in each frame. Moreover, Multi-Q also employs stateless Q-learning to determine the frame size for uplink transmissions and power split ratio of devices.

MDP model

To model the sequential decision process taken by the HAP and devices, we use an MDP model. It is defined as a tuple [\({\mathscr{S}}, {\mathscr{A}}, {\mathscr{T}}, {\mathscr{R}}\)]. Here, the state space is denoted as \({\mathscr{S}}\). The action space \({\mathscr{A}}\) includes a set of actions a. A policy \(\pi\) returns the action a for state s. After an agent takes action a in state \(s^{t}\), the system will transition to a new state \(s^{t+1}\) with a transition probability of \({\mathscr{T}}(s^{t+1} | s^{t}, \pi (s^{t}))\). In addition, the agent obtains a reward \({\mathscr{R}}(s^{t+1} | s^{t}, \pi (s^{t}))\).

Our downlink MDP is defined as follows:

-

State: A downlink state \(\check{s} \in {\check{\mathscr{S}}}\) includes the channel conditions of all devices. Each state is defined as \(\check{s}=[h_{1}, h2, \dots , h_N]\).

-

Action: The downlink action space is defined as \({\check{\mathscr{A}}}=[\check{a}_{1}, \check{a}_{2}, \dots ]\). Each downlink action \(\check{a}=[p_{1},p_{2},\dots ,p_N]\) represents the downlink NOMA power allocation for all users at the HAP.

-

Transition probability: We consider a model-free MDP model. Hence, the transition probability is unknown.

-

Reward: The reward function \({\check{\mathscr{R}}}\) is the throughput of downlinks, see Eq. (1).

The uplink MDP is defined as follows:

-

State: An uplink state \(\hat{s_{i}} \in {\hat{\mathscr{S}}}\) includes the channel condition and battery level of user \(U_{i}\). Formally, a state of user \(U_{i}\) is defined as \(\hat{s_{i}}=[h_{i}, E_{i}]\).

-

Action: An uplink action \(\hat{a} \in {\hat{\mathscr{A}}}\) includes time slot selection \(\delta _{i}\) and transmission probability \(\rho _{i}\). Thus, an uplink action is defined as \(\hat{a_{i}}=[\delta _{i}, \rho _{i}]\), which represents the fact that user \(U_{i}\) selects the slot indexed by \(\delta _{i}^{t}\) and transmits with probability \(\rho _{i}\).

-

Transition probability: The transition probability between states is unknown.

-

Reward: The reward function \({\hat{\mathscr{R}}}\) is the transmission rate of uplinks, see Eq. (5).

Q-learning

We employ two types of Q-learning methods, conventional Q-learning33 and stateless Q-learning34. Both conventional Q-learning and stateless Q-learning learn Q-values. However, conventional Q-learning learns Q-value for action and state pairs, while stateless Q-learning learns Q-value just for actions without any states.

Conventional Q-learning

Q-learning learns the optimal policy based on a Q-table. A Q-table is indexed by a state-action pair \((s_{t}, a_{t})\), and returns the corresponding Q-value \(Q(s_{t}, a_{t})\). Each Q-value \(Q(s_{t}, a_{t})\) represents the expected discounted reward for taking action \(a_{t}\) in state \(s_{t}\)33. The aim of Q-learning is to calculate \(Q(s_{t}, a_{t})\) for each action and state pair. To learn the optimal policy, an agent first obtains its current state \(s_{t}\). Secondly, it looks up its Q-table to find the corresponding Q-values for state \(s_{t}\) and selects the action \(a_{t}\) with the highest Q-value. After the agent selects action \(a_{t}\), the system will return a corresponding reward \(r(s_{t}, a_{t})\). Then the agent observes its next state \(s_{t+1}\) and finds the highest Q-value. Lastly, the agent updates its Q-table based on its obtained reward and the highest Q-value for the next state. We denote \(\alpha\) as the learning rate factor, \(\gamma\) as the discount factor, where \(\alpha , \gamma \in [0,1]\). Concretely, Q-learning uses Bellman’s equation to update its Q-table as per

Stateless Q-learning

Stateless Q-learning34 learns the optimal policy without any states. The stateless Q-table only contains the value of actions. We denote \(\lambda \in [0,1]\) as the stateless learning rate and the reward is denoted as r(a). Thus, stateless Q-learning updates Q(a) using

Under this stateless setting, an agent maintains a Probability Mass Function (PMF), denoted as

which calculates the probability of taking action \(a_{i}\).

Multi-Q learning

Now we are ready to outline our proposed Q-learning approach, named Multi-Q, to solve Problem (7). Multi-Q is composed of three layers, namely the uplink, downlink, and stateless. Figure 3 shows the Multi-Q framework. The downlink and uplink layer adopt conventional Q-learning while the stateless layer employs stateless Q-learning. All layers use \(\epsilon\)-greedy for action selection. Thus, initially, each agent has \(\epsilon\) probability to randomly select an action. After that, we decay the value of \(\epsilon\) to ensure convergence. Concretely, at the downlink layer, the HAP is the agent to learn the downlink MDP action \(\check{a}=[p_{1},p_{2},\ldots ,p_N]\) which includes the power allocation for each user. The HAP starts with randomly selected power allocation first. During this warm-up period, the Q-table will update Q-values for each power allocation under each channel condition based on its corresponding throughput. A certain power allocation will obtain a high Q-value if it achieves high downlink throughput. Each time a power allocation is selected, its Q-value will be updated based on its past throughput, current throughput, and predicted future throughput. After several epochs, the HAP will mostly select the power allocation with the highest Q-value to pursue high downlink throughput. Consequently, with the convergence of the learning process, for each given channel state, the best power allocation will achieve the highest Q-value. Thus, for each downlink transmission, the HAP will learn the certain transmission power \(p_{i}\) for each user to employ downlink NOMA transmission. At the uplink layer, each IoT device is an agent that independently learns its uplink MDP action \(\hat{a_{i}}=[\delta _{i}, \rho _{i}]\) which includes uplink transmission probability and slot selection. That means, in each frame, each device will learn to select a certain uplink transmission slot and probability to transmit. Similar to the downlink layer, the Q-table will update the Q-value for each action-state pair until converges. Therefore, for a given channel state, the uplink transmission slot and transmission probability with the highest transmission rate will obtain the highest Q-value. In the stateless layer, the system determines the uplink frame size and downlink power split ratio. During the warm-up period, the system randomly determines the uplink frame size and the downlink power-splitting ratio. For each frame size and power splitting ratio, the Q-table will update the Q-value based on the sum rate. After several epochs, the system will select the frame size and power-splitting ratio with the highest Q-value. The frame size and power splitting ratio that obtains a high system sum rate will get a high Q-value. Each time an action is selected, its Q-value will be updated based on its past reward, current reward, and possible future reward. Until convergence, the best frame size and power-splitting ratio will have the highest Q-value. Let \(\Phi\) denote the number of epochs and \(\phi\) denote the number of frames inside each epoch. Next, we present how each layer works.

Multi-Q includes downlink, uplink, and stateless layer. In the downlink layer, the HAP employs Algorithm 1, which is denoted as \(A_{1}\) in the figure, to learn downlink power allocation. In the uplink, each user independently employs Algorithm 2, which is denoted as \(A_{2}\), to learn its own slot selection and transmission probability. Then the stateless layer collects the reward of both uplink and downlink for one epoch and then employs Algorithm 3 to determine the frame size and power split ratio.

Downlink layer

In the downlink layer, the HAP performs conventional Q-learning33. Algorithm 1 demonstrates the steps of this layer. Each learning phase consists of \(\phi\) time frames. Firstly, the HAP initializes its Q-table and learning parameter \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\). During each time frame t, the HAP collects the channel condition \(h_{i}^{t}\) of user \(U_{i}\) to obtain its downlink state \(S_{t}\), see line 5. After that, the HAP uses \(\epsilon\)-greedy to select an action \(A_{t}\) which governs the transmission power allocation for all users. Concretely, with probability \((1-\epsilon )\), the HAP selects the action \(A_{t}\) with the highest Q-value for state \(S_{t}\), see line 10. After taking action \(A_{t}\), each user collects its individual reward \(r_{i}^{t}\) and reports to the HAP. The HAP sums all rewards together to obtain the downlink reward \(R_{t}\), see line 13. Then, the HAP observes its next state and finds the highest Q-value for the next state to update its Q-table.

Uplink layer

In the uplink layer, each user acts as an agent to independently perform conventional Q-learning, see Algorithm 2. In each time frame \(t \in \phi\), each user uses its channel condition \(h_{i}^{t}\) and battery level \(E_{i}^{t}\) as its current state \(s_{i}^{t}=[h_{i}^{t}, E_{i}^{t}]\), see line 5. Based on \(\epsilon\)-greedy, each user selects an action \(a_{i}^{t}\) that governs its transmission slot selection and transmission probability. Specifically, each user either selects an action randomly, see line 8, or selects the action with the highest Q-value, see 10. After that, each user observes its next state \(s_{i}^{t+1}\), see line 13, and finds the corresponding highest Q-value, see 14. Then, each user updates its Q-table, and repeats the aforementioned steps.

Stateless layer

In the stateless layer, the learning phase consists of \(\Phi\) epochs, see Algorithm 3. At the beginning of each epoch \(\kappa\), the system selects an action \(a_{\kappa }=[M, \theta ]\) that governs the uplink frame size and downlink power split ratio. With probability \(\epsilon\), the system randomly selects an action, see line 5. Otherwise, the system will select an action with the highest probability, see line 9. After that, the system collects the reward for uplink and downlink, see line 11, 12, and accumulates downlink and uplink reward during epoch \(\kappa\) to obtain stateless reward, see line 13. Then, the system updates its Q-table and PMF. It then repeats the said steps.

Evaluation

We conducted our simulation using Matlab running on a machine with 8-Core Intel Core i9 @2.3 GHz with 16 GB of RAM. The path loss at reference distance 1 m is − 20 dB27. We fixed both the uplink length \(\tau _{up}\) and downlink length \(\tau _{down}\) to 1 s. We consider a packet size of \(L=21\) bytes as per the IPv4 standard, which includes 20 bytes for header and one byte of data. The average energy consumption rate \(\zeta\) is 18 nJ/bit35. Thus, the minimum energy consumption for transmission is \(\varepsilon _0 = \zeta \times L = 3.024\) \(\upmu\)J. The battery capacity \({\mathscr{B}}\) of each user is set to \(5 \varepsilon _0\). According to the non-linear model in31, we set the energy conversion efficiency parameters as M = 0.02 W, a = 1500, and b = 0.0014.

We compare Multi-Q against round-robin, TDMA, and Aloha. The round-robin protocol is used for both uplink and downlink transmissions; i.e., the HAP transmits downlink signals to each device in turn and devices transmit to the HAP in turn. As for TDMA and Aloha, these protocols are for uplink transmissions only. Both these two protocols consider downlink NOMA with uniform power allocation. Then during uplink, TDMA assigns a dedicated time slot to each device. As for Aloha, devices with sufficient energy contend for an uplink time slot randomly. We measure and compare the performance of these protocols from three aspects including average system sum rate, average downlink transmission rate, and average uplink transmission rate. Apart from that, we study different HAP transmit power, device location, and power split ratio. Each simulation has 30,000 time frames. We collect the result in the last 300 frames after convergence, and plot the average of ten simulation runs. In terms of computational complexity, Multi-Q involves three layers of Q-learning. We analyze the computational complexity of each server at time t. For the downlink layer and uplink layer, each server needs to determine the Q-value of a state-action pair. This Q-value is calculated as per (8), which takes O(1) time. For the stateless layer, a server needs to determine the Q-value of an action which is calculated as per (9). For each layer, the Q-value is updated only according to the reward of servers, which is calculated as per (5). Observe that (8), (9), and (5) only involve multiplication and addition operations. Moreover, Multi-Q is able to suit larger-scale networks. However, the downlink layer computational complexity may increase with a larger scale since it calls for global information on the server.

Convergence

To study convergence, users are placed at a distance of 1, 5, and 9 m from the HAP. We run our simulator for 200 iterations and each iteration contains 150 frames. We plot both uplink and downlink rates in Fig. 4. There is a warm-up period of 15,000 frames. Referring to Fig. 4, we can see that both uplink and downlink rates converged after 140 iterations. Concretely, the downlink rate converged to around 34 b/s/Hz, and the uplink rate converged to around 13.66 b/s/Hz.

Learning parameter

We now study learning parameters. Specifically, we study the uplink and downlink layer learning rate including uplink learning rate \(\alpha _{u}\) and downlink learning rate \(\alpha _d\), the frame size and power ratio layer learning rate \(\lambda\), discounting factor \(\gamma _d\), and warm-up period. We can see from Fig. 5 that each learning parameter combination converged to a different sum rate. With a short warm-up period, the system will experience more randomness during convergence. The system converges faster when the frame size and power ratio layer uses a learning rate of \(\lambda\).

HAP transmission power

We vary the transmission power of the HAP from 1 to 5 W. User are located at a distance of 1, 5, and 9 m to the HAP. The frame size is three for Aloha and TDMA. The path loss exponent is \(n=2.7\)36.

Figure 6a demonstrates the average sum rate of both uplink and downlink. The sum rate of uplink and downlink increases with a higher HAP transmission power for all methods. Concretely, both uplink and downlink rate increase with a higher HAP transmission power as shown in Fig. 6b. The reason for the increase in uplink rate is because users harvest more energy with a higher HAP transmission power. Thus users are able to transmit with a higher transmit power. Similarly, a higher HAP transmit power leads to a higher downlink rate.

Multi-Q performs best when we vary the HAP transmission power from 1 to 5 W. From Fig. 6a, It is clearly that Multi-Q always reaches the highest sum rate from 1 to 5 W. Moreover, Multi-Q reaches an average of 44.3 b/s/Hz, which is 6× that of Aloha, 2.3× that of TDMA, and 30% more than round-robin. From Fig. 6b, Multi-Q reaches an average downlink transmission rate of 31.9 b/s/Hz which is the highest among all methods and achieves 6.6 b/s/Hz more than round-robin. TDMA and Aloha are even worse and just achieved zero downlink rates. The reason is because both TDMA and Aloha adopt uniform power distribution for each user during downlink. A uniform power distribution leads to decoding failures. Furthermore, Multi-Q performs better than round-robin for both uplink and downlink. Concretely, Multi-Q achieves an average of 12.4 b/s/Hz and 31.9 b/s/Hz rate for uplink and downlink, which is 6.6 b/s/Hz and 4.1 b/s/Hz more than that of round-robin, respectively. This is because Multi-Q users utilize the whole downlink period to receive data. On the other hand, for round-robin, users only receive data when it is polled by the HAP. In terms of downlink, round-robin experiences idle slots when users do not harvest sufficient energy. However, Multi-Q is able to avoid idle slots by dynamically adjusting the frame size and transmission probability based on the battery level and channel condition of users. Overall, Multi-Q performs significant advantages in terms of sum rate which is 6 times of Aloha method. Simultaneously, Multi-Q also shows great advantages in terms of downlink rate which is 26% more than Round Robin and 100% more than TDMA and Aloha.

User location

We set five groups of user locations and the total distance from each group of devices to HAP is 15 m. We start from the group where each user is placed 5 m from the HAP. As channel gain disparity improves SIC decoding37, we move users to different locations to obtain different channel gain conditions. Specifically, we consider five groups of user locations. The distance (in meters) of each user to the HAP is as follows: [5, 5, 5], [4, 5, 6], [3, 5, 7], [2, 5, 8], and [1, 5, 9]. The frame size is three for Aloha and TDMA. The path loss exponent is \(n=2.7\)36.

As shown in Fig. 7a, the average sum rate of both uplink and downlink increases when users have a more significant distance difference. This is because when we place users at different distances to the HAP, users experience significant differences in channel gains. Thus, the energy harvested by users vary considerably. This also means there will be one user located close to the HAP who transmits at a high power while another user located farther from the HAP that uses a low transmit power. This difference in transmit power helps increase the number of SIC decoding successes.

Multi-Q outperforms all other methods, especially when the distance between users is large. Specifically, Multi-Q achieves an average sum rate of 32 b/s/Hz for different locations. Simultaneously, Aloha, Round Robin, and TDMA achieve an average sum rate of 2.5 b/s/Hz, 29 b/s/Hz, and 4 b/s/Hz, respectively. When users are located at a distance of 1 m, 5 m, and 9 m to the HAP, Multi-Q achieves a sum rate of 44 b/s/Hz, which is six times that of Aloha, three times higher than TDMA, and 30% more than round-robin. The reason why Multi-Q performs better is because both Aloha and TDMA obtain zero downlink rate as shown in Fig. 7b. As both Aloha and TDMA employ uniform power distribution in the downlink, they always experience failures during downlink transmissions. When compared to round-robin, Multi-Q outperforms round-robin because Multi-Q simultaneously learns the frame size and transmission probability that avoid idle slots. Overall, Multi-Q always achieves the highest sum rate for different user locations which is an average of 11 times Aloha, 7 times TDMA and 10% more than Round Robin. Besides, Multi-Q shows great advantages in terms of downlink rate which is 100% higher than TDMA and Aloha, and 5% higher than Round Robin.

Power split ratio

Users are located at a distance of 1, 5, and 9 m to the HAP. The HAP transmission power is 3 W and the path loss exponent is \(n=2.7\). We vary the split ratio from zero to one with a step size of 0.1. Initially, the power split ratio is zero, meaning all received power is for energy harvesting. After that, we increase the power split ratio to 0.1. Thus, there is 10% power redirected for data reception and the remaining 90% is used for energy harvesting. Then we increase the power split ratio in steps of 0.1 until it reaches 1.0. Referring to Fig. 8a, Multi-Q achieves a sum rate around 44 b/s/Hz; it is able to converge to the optimal power split ratio starting from any initial ratio. The achieved sum rate of round-robin continues to rise until the power split ratio increases to 0.9. This is because when we increase the power split ratio, there will be more power distributed for downlink data reception and less power for energy harvesting. From Fig. 8b round-robin obtains an average of 25.3 b/s/Hz rate for downlink and 5.7 b/s/Hz for uplink. The downlink rate of round-robin is approximately 5× its uplink rate. Therefore, even if the uplink rate of round-robin decreases, the sum rate increases since the downlink rate increases more than the uplink rate. As the power split ratio increases from 0.9 to 1.0, the sum rate of round-robin decreases since there is no power distributed for downlink rate. However, Aloha and TDMA experience a decrease when we increase the power split ratio from 0 to 1.0. The reason is because users employ uniform power allocation for downlinks. Thus each user fails to decode the received packet since there is no difference between the transmit for each user. Further, for higher power split ratios, resulting in less harvested energy or transmit power, the uplink rate is appreciably lower.

We have also studied the performance of different frame sizes for Aloha. As shown in Fig. 8a, Aloha achieves its highest sum rate when the frame size is one. Although a larger frame size means fewer collisions, frame size one performs better than a larger frame size since we consider SIC, which allows decoding of multiple transmissions in the same slot. Moreover, a smaller frame size lengthens the transmission period, thus users are able to transmit longer.

Among all methods, Multi-Q performs best. Multi-Q achieves an average of 44 b/s/Hz sum rate, which is 9.8 times more than TDMA, 6.5 times that of Aloha when the frame size is one, and 1.4 times higher than round-robin. This is because Multi-Q simultaneously learns the power split ratio, frame size, uplink transmission probability, uplink slot selection, and downlink power allocation for all users. Specifically, Multi-Q learns the best frame size and slot selection to avoid uplink decoding failure and idle. Learning downlink power allocation for each user enhances decoding success. It also learns the power split ratio to balance uplink and downlink rates. Overall, Multi-Q shows great advantages in terms of sum rate over all other methods for different pre-set split ratios. Moreover, Multi-Q always achieves the highest downlink rate and uplink rate, which is 31.5 b/s/Hz and 12.5 b/s/Hz, respectively.

Conclusion

This paper has studied joint uplink and downlink transmissions in a wireless powered network that uses FSA and NOMA. In this respect, it has outlined a novel solution called Multi-Q that allows an HAP and devices to learn the optimal transmission policy. Specifically, for each system state, the HAP learns to optimize its transmit power allocation and frame size for uplinks. Similarly, devices learn the optimal power split ratio and transmission probability for each frame size. Advantageously, Multi-Q does not assume non-causal information and state transition probability. The simulation results show that Multi-Q achieves an average sum rate of 44 b/s/Hz which is 6× that of Aloha, 2.3× that of TDMA, and 30% more than round-robin. This is because our learning-based method Multi-Q can flexibly schedule the system to respond to different network conditions. Consequently, Multi-Q is able to obtain the best transmission strategy when compared to Aloha, TDMA, and so forth. Our work can be effortlessly extended to real-world IoT deployments like smart agriculture, smart transportation, smart cities, and so forth. This would better provide charging solutions and communications for agricultural sensors, parking sensors, and the like. As future work, we also aim to investigate whether our approach can be applied in multi-hop networks that include RF-energy harvesting relay nodes and extend our approach to be suitable for moving end devices such as moving vehicles. Moreover, an interesting future work is to study the performance of an approach based on deep Q-learning and/or an actor-critic.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yu, H. & Chin, K.-W. Maximizing sensing and computation rate in ad-hoc energy harvesting IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 5434–5446 (2023).

Nguyen, D. C. et al. Federated learning for internet of things: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 23, 1622–1658 (2021).

Ren, H. & Chin, K.-W. Novel tasks assignment methods for wireless-powered IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 10563–10575. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3121415 (2022).

Talla, V., Kellogg, B., Ransford, B. & Naderiparizi, S. Powering the next billion devices with Wi-Fi. In ACM CoNEXT (2015).

Perera, T. D. P., Jayakody, D. N. K., Sharma, S. K., Chatzinotas, S. & Li, J. Simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT): Recent advances and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 20, 264–302 (2017).

Zhang, R. & Ho, C. K. MIMO broadcasting for simultaneous wireless information and power transfer. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 12, 1989–2001 (2013).

Liu, L., Zhang, R. & Chua, K.-C. Wireless information and power transfer: A dynamic power splitting approach. IEEE Trans. Commun. 61, 3990–4001 (2013).

Lu, X., Wang, P., Niyato, D., Kim, D. I. & Han, Z. Wireless networks with RF energy harvesting: A contemporary survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 17, 757–789 (2014).

Saito, Y. et al. Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) for cellular future radio access. In IEEE VTC 1–5 (2013).

Islam, S. R., Avazov, N., Dobre, O. A. & Kwak, K.-S. Power-domain non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) in 5G systems: Potentials and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 19, 721–742 (2016).

Yu, H., Chin, K.-W. & Soh, S. Charging RF-energy harvesting devices in IoT networks with imperfect CSI. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 17808–17820 (2022).

Syam, M., Che, Y. L., Luo, S. & Wu, K. Uplink throughput maximization for low latency in wireless powered communication networks. In IEEE 19th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT) 1002–1006 (2019).

Syam, M., Che, Y. L., Luo, S. et al. Joint downlink-uplink throughput optimization in wireless powered communication networks. In IEEE/CIC International Conference on Communications in China (ICCC) 852–857 (2019).

ElDiwany, B. E., El-Sherif, A. A. & ElBatt, T. Optimal uplink and downlink resource allocation for wireless powered cellular networks. In IEEE PIMRC 1–6 (2017).

Diamantoulakis, P. D., Pappi, K. N., Karagiannidis, G. K., Xing, H. & Nallanathan, A. Joint downlink/uplink design for wireless powered networks with interference. IEEE Access 5, 1534–1547 (2017).

Lv, K., Hu, J., Yu, Q. & Yang, K. Throughput maximization and fairness assurance in data and energy integrated communication networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 5, 636–644 (2017).

Yang, Z., Xu, W., Pan, Y., Pan, C. & Chen, M. Optimal fairness-aware time and power allocation in wireless powered communication networks. IEEE Trans. Commun. 66, 3122–3135 (2018).

Qin, C., Ni, W., Tian, H. & Liu, R. P. Joint rate maximization of downlink and uplink in multiuser MIMO SWIPT systems. IEEE Access 5, 3750–3762 (2017).

Qin, C., Ni, W., Tian, H., Liu, R. P. & Guo, Y. J. Joint beamforming and user selection in multiuser collaborative MIMO SWIPT systems with nonnegligible circuit energy consumption. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 67, 3909–3923 (2017).

Li, S., Wan, Z. & Jin, L. Joint rate maximization of downlink and uplink in NOMA SWIPT systems. Phys. Commun. 46, 101324 (2021).

Baidas, M. W., Alsusa, E. & Shi, Y. Network sum-rate maximization for swipt-enabled energy-harvesting downlink/uplink NOMA networks. In 23rd International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC) 1–6 (2020).

Baidas, M. W., Alsusa, E. & Shi, Y. Resource allocation for SWIPT-enabled energy-harvesting downlink/uplink clustered NOMA networks. Comput. Netw. 182, 107471 (2020).

Rezvani, S., Mokari, N. & Javan, M. R. Uplink throughput maximization in OFDMA-based SWIPT systems with data offloading. In Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE) 572–578 (2018).

Na, Z., Zhang, M., Jia, M., Xiong, M. & Gao, Z. Joint uplink and downlink resource allocation for the internet of things. IEEE Access 7, 15758–15766 (2018).

Xiong, C., Lu, L. & Li, G. Y. Energy efficiency tradeoff in downlink and uplink TDD OFDMA with simultaneous wireless information and power transfer. In IEEE ICC 5383–5388 (2014).

Yao, Q., Quek, T. Q., Huang, A. & Shan, H. Joint downlink and uplink energy minimization in WET-enabled networks. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 16, 6751–6765 (2017).

Lee, S. & Zhang, R. Cognitive wireless powered network: Spectrum sharing models and throughput maximization. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 1, 335–346 (2015).

Ramezani, P. Extending Wireless Powered Communication Networks for Future Internet of Things. Master’s thesis, University of Sydney (2017).

Patel, P. & Holtzman, J. Analysis of a simple successive interference cancellation scheme in a DS/CDMA system. IEEE JSAC 12, 796–807 (1994).

Powercast. P2110B powerharvester receiver (2016).

Boshkovska, E., Ng, D. W. K., Zlatanov, N. & Schober, R. Practical non-linear energy harvesting model and resource allocation for SWIPT systems. IEEE Commun. Lett. 19, 2082–2085 (2015).

White, C. C. III. & White, D. J. Markov decision processes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 39, 1–16 (1989).

Watkins, C. J. & Dayan, P. Q-learning. Mach. Learn. 8, 279–292 (1992).

Claus, C. & Boutilier, C. The dynamics of reinforcement learning in cooperative multiagent systems. AAAI/IAAI 1998, 2 (1998).

Adame, T., Bel, A., Bellalta, B., Barcelo, J. & Oliver, M. IEEE 802.11 AH: The WiFi approach for M2M communications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 21, 144–152 (2014).

Miranda, J. et al. Path loss exponent analysis in wireless sensor networks: Experimental evaluation. In 11th IEEE International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN) 54–58 (Bochum, 2013).

Maraqa, O., Rajasekaran, A. S., Al-Ahmadi, S., Yanikomeroglu, H. & Sait, S. M. A survey of rate-optimal power domain NOMA with enabling technologies of future wireless networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 22, 2192–2235 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of Henan Province, 242102210197, Science and Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province, 24HASTIT036, and Key Scientific Research Projects of Universities in Henan Province, 25B510012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceptualized the study, conceived the experiment, and initial manuscript drafting; Y.L., Y.M., and W.W. contributed to data collection and analysis; All authors were involved in critically revising the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Mu, Y., Zhang, G. et al. Learning uplinks and downlinks transmissions in RF-charging IoT networks. Sci Rep 14, 28922 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79498-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79498-6