Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in women globally, stemming from gene mutations that prompt irregular cellular growth and subsequent tumor development. Early-stage detection of cancer cells results in a remarkable 99% survival rate. This research presents a microwave imaging technique for the non-invasive identification of tumors in the initial stages within the women’s breast. A low-cost antenna array with an Artificial Magnetic Conductor (AMC) is proposed, featuring a compact structure size of 37.2 \(\times\) 37.2 mm\(^{2}\). The AMC, a metamaterial, acts as a reflective surface to enhance frequency selectivity, specifically at 8.48 GHz. The maximum gains reached 9.35 dBi in simulated results and 10.51 dBi in measured results. The fabricated antenna validates the simulated findings, and its operational efficiency has undergone experimental validation. Moreover, fidelity factors in face-to-face (FtF) and side-by-side (SbS) scenarios are delineated. The antenna, operating as a transceiver, is applied to a modeled breast phantom across five distinct cases for numerical simulations pertaining to cancer cell detection applications. The outcomes of this research bear considerable implications for advancing early-stage breast cancer detection methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most frequent malignancy among women globally is breast cancer1,2. Breast cancer will affect American women during their lives at a rate of 12%2. Breast cancer claimed the lives of 626,679 women out of 2.1 million new cases reported in 20181. It is predicted that the number of cases of breast cancer will rise from 14 million to 22 million over the next 20 years3,4. These statistics indicate the dangers of breast cancer in women5,6,7. The most successful method of treating breast cancer is thought to be an early diagnosis8, and the survival rate reaches 99% with non-invasive detection of cancer cells9.

Doctors use X-ray mammography, MRI, and ultrasound to identify breast cancer10,11. Mammography has led to incorrect diagnoses and outcomes, negatively impacting patient quality of life8. Women are deterred from regular checkups due to X-rays and discomfort during imaging5,7,12. Poor ultrasound imaging makes Cancerous cells difficult to distinguish from normal cells7,8,12. MRI is sensitive to dense breasts but inaccurate diagnostic due to placement4,5,12. Researchers are exploring a new technique using microwaves to address faults and testing constraints7,10,12. Microwave Imaging (MWI) is a low-cost alternative to MRI that offers good data rate accuracy and comfortable placement. It is also non-ionizing, less complex, and has low power density6. MWI depends on alterations in the backscattered signal brought about by variations in the dielectric properties of the biological tissues5,11,12.

The antenna creates microwave electromagnetic pulses that irradiate the human cells. Depending on the human cell’s dielectric constant, some of the microwave energy the antenna delivers to the cells scatters back to the receiver4,13. A high microwave backscattered signal readily identifies a cancerous cell. The dispersed back signals can be utilized to gather additional data for medical diagnostic reasons1,12. Antenna arrays are popularly used for microwave imaging to detect breast tumours15,16,17. However, these antenna arrays require a large number of antenna elements to achieve high gain, which is an important factor for proper imaging of tumours18,19,20. In21, a tapered slot antenna loaded with parasitic components has been proposed, operating in 3.8–10.1 GHz frequency range. The antenna occupied an area of only 29 mm \(\times\)26.6 mm but offered a gain of only 6.8 dBi. Incorporating an artificial magnetic conductor (AMC) significantly improves the antenna’s gain due to its zero-reflection phase at its resonant frequency14.

Some of the studies have employed AMC-backed antennas for breast cancer detection, especially in the field of microwave imaging systems. In5, a CPW feed EBG antenna has been proposed, which offers a gain improvement of 5 dBi. In7, a CPW-fed antenna backed by square ring resonators has been proposed. The antenna operates in the wide bandwidth from 2.8 GHz to 10 GHz, with a peak gain of 11.8 dBi. However, the antenna occupied a large area of 50 mm \(\times\)76 mm. In11, another CPW-fed antenna backed by negative index metamaterials has been proposed, operating in 4–15 GHz. It occupied a large surface area of 80 mm \(\times\)61 mm while offering 7.56 dBi gain. In22, an AMC-backed patch antenna has been proposed having an area of 50 mm \(\times\)50 mm and 8.47 dBi gain. Another ultrawideband antenna backed by AMC has been proposed in23, operating in the 2.9–7 GHz frequency range. It occupied a small area of 28 mm \(\times\)34 mm, but the offer gain was also low. A recent work reported an AMC-based antenna, with a gain of only 4 dBi24.

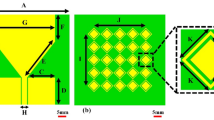

The proposed research introduces a novel integration of an AMC within the antenna design, significantly enhancing frequency selectivity and gain, which is critical for effective breast cancer detection. The AMC’s structural innovation is meticulously illustrated in Figure 1, depicting the detailed configuration of unit cells in the rear (Fig. 1(a)), front (Fig. 1(b)), and individual unit cell views (Fig. 1(c)). Inspired by the metasurface antenna-on-chip design proposed in25, this arrangement optimizes the antenna’s performance at the target frequency of 8.48 GHz by improving frequency selectivity and gain. Specifically, the AMC increases peak gain from 9.35 dBi in simulations to 10.51 dBi in measurements, thereby enhancing the sensitivity and resolution of the microwave imaging system. Furthermore, unwanted surface interactions, a common limitation in conventional designs, are minimized, thus improving overall antenna efficiency and imaging quality26. This approach mirrors the strategies in27, where metasurface technology and electromagnetic bandgap structures enhance isolation between radiating elements, improving antenna performance in wearable biomedical devices. The design synergizes the stability of microstrip patch antennas with the high gain and directivity of Vivaldi antennas, achieving superior performance through a hybrid approach. The design also incorporates energy-efficient principles from28, using virtual antenna arrays to minimize energy consumption while maintaining signal robustness. Additionally, we employ a metamaterial-based impedance-matching circuit approach similar to29, enhancing gain and bandwidth for a broader operational range and stable imaging performance across diverse breast tissue densities.

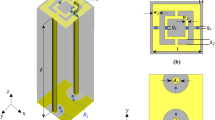

Figure 2 delineates this innovative combination, with the microstrip patch (Fig. 2(a)) providing stability around 8.48 GHz and the Vivaldi elements (Fig. 2(b)) contributing to enhanced gain and directivity. This dual design strategy ensures a robust and efficient system for non-invasive breast cancer detection, capitalizing on the complementary strengths of both antenna types. To substantiate our theoretical advancements, we fabricated and experimentally validated the proposed antenna system, assessing its performance using breast phantom simulations across five distinct scenarios, including normal and cancerous tissues. This validation, encompassing face-to-face (FtF) and side-by-side (SbS) fidelity evaluations, highlights the practical applicability and effectiveness of the system in real-world contexts. Our comprehensive analysis, covering areas often overlooked in existing literature, confirms the sensor’s potential for early-stage cancer diagnosis. A pivotal aspect of our design is its cost-effectiveness, facilitating widespread accessibility in various healthcare settings, including resource-limited environments. By prioritizing affordability without compromising performance, our antenna design addresses a critical gap in breast cancer detection technologies, promoting broader adoption and potentially improving global health outcomes. This affordability ensures that advanced detection technology can reach a larger population, fostering better health outcomes through early detection.

Design of AMC

The proposed AMC’s structure comprises a 5 \({\times }\) 5 array of the concentric rhombuses on an FR4 substrate. The proposed MTM unit cell for a microstrip patch antenna is shown in Fig. 1. The ground’s annealed copper structure is a hollow asteroid in wand centered by a hollow rhombus of the same composition; each of them plays an important role in capturing the emitted wave for a specific purpose, as shown in Fig. 1(a). Two concentric rhombuses of annealed copper are engraved on the FR4 substrate with the defective ground structure at the bottom as shown in Fig. 1(b), and the unit cell is shown in Fig. 1(c). The design’s dimensions are shown in Table 1. Commercially available CST software was used to design the AMC.

The designed AMC is shown in Fig. 2. The proposed antenna-based sensor consists of two circular microstrip feeders connected to the patch. The main purpose of choosing this shape is to capture the antenna’s gain. As shown in Fig. 2(a), the patch is rectangular with a cut rhombus in the middle and another rhombus in the middle, which is used to capture the reflection rates. Fig. 2(b) shows that the Vivaldi form inspired the antenna’s design. The perspective view of the entire design is given in Fig. 2(c). The substrate of choice is FR4 due to the same reasons mentioned earlier. Table I summarizes all the physical dimensions of the proposed antenna sensor.

The proposed antenna design integrates microstrip patch and Vivaldi antenna principles, optimized using an AMC for enhanced performance. Initially, the microstrip patch antenna (Fig. 2(a)) was designed for stable frequency operation around 8.48 GHz.

The antenna’s ground plane geometry, depicted in Fig. 2(b), is inspired by the Vivaldi design, which is selected for its advantages in achieving a specific resonance frequency and optimal field distribution. This geometry aids in achieving a resonance point close to 8.5 GHz, where the difference in dielectric properties between the breast phantom’s components is most pronounced. This contrast enhances the sensor’s sensitivity for the early detection of breast cancer by increasing the distinction between healthy and malignant tissues. A Metamaterial-Inspired AMC layer (Fig. 2(c)) is strategically integrated into the antenna design to enhance its reflective properties at the target frequency of 8.48 GHz. The AMC, acting as a high-impedance surface, reflects incident electromagnetic waves in phase, resulting in increased antenna gain, improved frequency selectivity, and reduced back radiation. This metamaterial characteristic is particularly advantageous for microwave imaging applications, as it amplifies the electromagnetic field strength towards the breast phantom model, thereby enhancing detection accuracy. This combination resulted in peak gains of 9.35 dBi in simulations and 10.51 dBi in measurements, providing a low-cost, high-performance solution for non-invasive breast cancer detection.

The transmission and reflection coefficients of the designed AMC have been rigorously simulated and are illustrated in Fig. 3. Integration of the antenna atop the AMC substrate promises superior radiation characteristics, notably evidenced by the resonant behavior of the reflection coefficient, prominently observed at 8.48 GHz. Impedance discontinuities within the transmission medium can induce reflections of electromagnetic waves quantified by the reflection coefficient. This metric is pivotal in assessing the Voltage Standing Wave Ratio (VSWR) and evaluating the impedance matching between feeder and load. Defined as the ratio of incident wave amplitude to that of the reflected wave, the reflection coefficient (s\(_{11}\)) is delineated in Fig. 3(a), both with and without the intended AMC layer. The AMC layer primarily affects the matching around the resonance frequency, while the response in the start and stopband regions remains relatively unaffected. For optimal Radio Frequency (RF) signal concentration towards a distant target, high-gain antennas represent the preferred choice, leveraging their ability to amplify transmitted power, thereby intensifying the received signal. Precise directional alignment ensures effective delivery of the RF signal, enhancing signal fidelity within the designated area of interest. Fig. 3(b) portrays the peak realized gain of the antenna sensor, showcasing a notable enhancement by a factor of 2 dBi around the 8.48 GHz center frequency with the incorporation of the AMC layer.

The maximum gains achieved with AMC and without AMC are 7.49 dBi and 9.467 dBi, respectively, at the resonance.

Experimental results and discussions

The LPKF PCB prototyping machine has been used to fabricate the antenna and the AMC structure, as shown in Fig. 4. The front view of the fabricated antenna is shown in Fig. 4(a), the backside view is shown in Fig. 4(b). The 5 \({\times }\) 5 AMC structure is shown in Fig. 4(c), and its ground plane consisting of annealed copper and concentric rhombus slots is shown in Fig. 4(d).

Return loss and realized gain

Using an Agilent PNA-L vector network analyzer (VNA), the return loss of the proposed structure, gain, and radiation pattern were experimentally measured, as shown in Fig. 5.

The return losses and realized gain of the antenna with and without AMC configuration are compared and indicated in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7. The performance of the antenna without AMC is shown in Fig. 6. The antenna without the AMC resonates at 8.54 GHz with a return loss of 42.44 dB based on the simulated results. With the experimental prototype, the antenna was observed to resonate at 8.18 GHz and 12.152 GHz with a return loss of 31.67 dB and 18.928 dB, respectively. The antenna’s performance with AMC is shown in Fig. 7. The return loss is significantly reduced, and the beam is greatly enhanced when the AMC backs the antenna. With the AMC, the antenna resonates at 8.48 GHz with 69.961 dB return loss according to the simulation results and at 8.12 GHz with 48.118 dB with the measured data. The results show that the AMC configuration significantly improves the return loss characteristics despite the small frequency difference between the simulated and measured results, which is attributed to manufacturing defects, such as improper soldering of the connectors.

Metallic structures possess inherent characteristics conducive to supporting surface waves, owing to their flat and smooth surfaces, facilitating the propagation of electromagnetic waves between the metal and the surrounding open space30. When encountering deformations, bends, or discontinuities on the surface, surface waves exhibit vertical radiation within the microwave spectrum31. The presence of interruptions such as gaps or cracks in the ground plane of the proposed antenna, as depicted in Fig. 4(b), leads to the transmission of surface waves vertically with zero reflection phase toward the Artificial Magnetic Conductor (AMC) structure situated on the trailing side of the antenna. The AMC structure, in turn, exhibits reflective properties towards newly emerging electromagnetic waves, resulting in constructive integration with the radiated wave from the antenna, thereby enhancing the antenna’s total gain32. The significant enhancement in total gain observed at the resonant frequency, particularly at 8.48 GHz, is attributed to the zero reflection phase characteristics exhibited by the proposed AMC configuration. Achieving impedance matching between the AMC and the antenna is imperative to ensure the manifestation of null reflective phase characteristics. To this end, a specific spacing distance of 23.8004 mm has been meticulously chosen between the AMC and the designated antenna, as delineated in Table 1. Deviations from this spacing distance, either greater or lesser, lead to cross-coupling effects that impair impedance matching and compromise the quality of zero-phase reflection. Comparative analyses reveal notable gains in antenna performance facilitated by including the AMC component. Specifically, at the resonant frequency, the measured gains without the AMC component are observed at 7.4 dBi and 8.68 dBi for calculated and measured detections, respectively. The simulated and measured cases yield 9.35 dBi and 10.51 dBi gains, respectively. These findings underscore the pivotal role played by the AMC structure in augmenting the antenna’s gain. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the proposed antenna exhibits a peak realized gain of 10.51 dBi, surpassing benchmarks documented in existing literature4,5,6,11,12,15.

Radiation pattern

Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 present the simulated two-dimensional radiation patterns of antennas in the xz (\(\phi\) = 0) and yz (\(\phi\) = 90) planes, respectively, both with and without the integration of an Artificial Magnetic Conductor (AMC) structure. As previously articulated, the AMC structure’s presence mitigates dorsal radiation while enhancing focus in a broad lateral direction. Notably, antennas equipped with the AMC structure exhibit a more pronounced radiation focus than those without one. The proposed AMC design contributes to improved radiation strength along the lateral direction, concurrently suppressing surface waves. This underscores the beneficial impact of the AMC on various radiation properties, including gain, directionality, and the reflection coefficient (S\(_{11}\))5. Experimental antenna evaluation is conducted within a laboratory setup, utilizing incremental steps in the \(\theta\) dimension while rotating along the \(\phi\) axis. The resultant two-dimensional beam patterns corresponding to resonant frequencies in the principal planes are illustrated in Fig. 10 and Fig. 11. The E-plane and H-plane, represented respectively by the xz plane (\(\phi\) = 0) and the yz plane (\(\phi\)= 90), serve as crucial reference frames for analyzing antenna radiation characteristics5,33. Implementing the AMC configuration induces a transition towards unidirectional radiation, as evidenced by the enhanced near-field efficiency. Given that broadside beams exert minimal influence on the orientation of the main lobes, emphasis is placed on E-plane and H-plane beam characteristics, resulting in enhanced antenna directionality. Noteworthy advancements include the emergence of a negligible back lobe, indicative of improved antenna performance. Higher-order excitation at frequencies exceeding 6 GHz minimizes the occurrence of nulls within the radiation pattern. Consequently, antennas integrated with an AMC exhibit superior matching and dissipate less energy than their counterparts lacking such structure5,34.

Time-domain performance

Assessing the proposed antenna’s efficacy, particularly concerning its applicability in microwave imaging systems, necessitates an evaluation of its performance in the time domain. While the antenna has exhibited commendable attributes in the frequency domain, these characteristics alone do not ensure satisfactory performance in the time domain. For time-domain analysis, a methodology involving the utilization of two identical antennas oriented in divergent directions is employed. This setup enables the second antenna to capture signals transmitted by the first, facilitating the assessment of input-output pulse fidelity, temporal efficiency, transmission coefficient (\(S_{21}\)), and group delay (\(\tau\)). Such analyses ascertain the antenna’s proficiency in time domain4,12,15.

Fidelity factor (FF) and pulse waveforms

The received and transmitted pulse waveforms shown in Fig 12., demonstrate negligible signal attenuation in the SbS and FtF directions. The fidelity factor is also determined by the highest cross-correlation value between the transmitted and received signals. It is possible to establish what (1) mentions4,12,15. Two suggested homogeneous antennas are spaced apart by 200 mm in Fig. 12 (a) and (b), depicting the input and received signals in both SbS and FtF directions.

where s(t) and r(t) are the transmitted and received signals.

Group delay measurements

The difference (\(\tau\)) as a function of frequency for both the FtF and SbS directions is shown and explained in Fig. 13. The delay in sending the signal from the transmitter to the receiver is known as the group delay (\(\tau\)). The following equation describes how the group delay, \(\tau\), is calculated4,15.

where the units (in radians) and (in radians/sec) correspond to the signal phase (\(\theta\)) and frequency (\(\omega\)), respectively.

Group delay has been obtained in both directions; the antennas are 200 mm apart. The group’s delay plot in the realistic linear FtF distribution allows the antenna to transmit brief pulses with negligible ringing and late-time distortion. It is best to use the designed antenna in the SbS direction, as evident from Fig. 13.

Setup for microwave imaging and results

Microwave imaging setup

The antenna’s frequency and time domain performance suggest that it can be employed for microwave imaging of the breasts to detect the presence of tumors35. Fig. 14 depicts the placement of four antennas around the breast to identify breast cancers. The breast phantom is shown in Fig. 14 (a). The simulation setup with antennas in FtF and SbS configuration are shown in Fig. 14 (b) and (c), respectively. The five layers make up the framework of the breast model. Breast tumors can be benign or cancerous. The truth is that once breast cancer cells spread to other places of the body, there is practically little hope of treating them. Our main focus has been on early detection because the survival rate at this stage is higher than 95%. Multiple tumors suggest that the patient is not in the early stages of the disease, and thus is not the aim of this study. Table 2 displays the attributes of these distinct levels.

Instead of using a coupling liquid to avoid strong skin reflection effects in the experimental setup, we implemented several alternative strategies. The antenna design and placement were optimized to reduce direct skin reflections. Integrating the AMC enhanced frequency selectivity and directional radiation properties, minimizing surface reflections. Additionally, the breast phantom material closely mimicked the dielectric properties of human breast tissue, reducing extraneous reflections. Advanced signal processing techniques, such as time-gating and frequency-domain filtering, were used to isolate relevant signals. These combined strategies enabled us to achieve reliable and reproducible results, effectively mitigating skin reflection effects.

Dielectric properties of breast tissues

Dielectric properties elucidate the interaction of electromagnetic waves with biological tissues at the cellular and molecular levels. When an electric field is applied to these tissues, the randomly oriented molecules within them align with the direction of the applied field. Consequently, the molecules become polarized when exposed to an external electric field. Simultaneously, this polarization process generates a smaller electric field in the opposite direction. The relaxation time (\(\tau\)) quantifies the duration of this polarization phenomenon. The resistance that molecules exhibit against an externally applied electric field can be elucidated by the complex permittivity of the material, which is expressed as36,37:

where \({\epsilon }_0\) is the permittivity of a vacuum given in Farads per meter (F/m), \({\epsilon }''_r\) is the loss factor, and \({\epsilon }'_r\) is the relative permittivity, often known as the dielectric constant. The loss factor may be written as follows:

where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency expressed in radians per second and \(\sigma\) is the material’s conductivity in Siemens per meter (S/m).

The relaxation time corresponding to the frequency can be used to characterize the frequency dependence of the permittivity, as shown in (3) and (4), or the dielectric dispersion of biological tissues.

Performance of the sensor with different tumors

This section distinguishes a clean breast from a newly cancerous breast using given and scattered signals. For this purpose, the non-invasive stage of breast cancer, i.e., early stage, is selected. Researchers say detecting cancer cells in the non-invasive stage has a 99% survival rate9. Another study reported a 97% survival rate41. A model based on the electrical attributes of the tumor and normal breast structures is designed, as explained in Table 2 and shown in Fig. 14(a). Also, the selected scan angle is explained in Fig. 14(b). The results were excellent, as shown in Fig. 15. The reflection coefficient with normal breast is shown in Fig. 15(a) and that with a tumor is shown in Fig. 15(b).

Excellent results are observed, especially in the range of 4 GHz to 4.06 GHz and 6.6 GHz to 7 GHz, because there is a difference in the vibration (x-axis) and the reflection coefficient (y-axis). This difference in both themes makes it much easier to distinguish an early cancerous breast from a normal breast. In the range of 4GHz to 4.06 GHz, there is a large difference between the signal of a clean breast and a newly cancerous breast, so that the difference in reflection coefficient for a newly cancerous breast is approximately -69 dB, but for a normal breast is approximately -75 dB at an oscillator of 0.00582 GHz, which is equal to 5.82 MHz, as shown in Fig. 16(a). There is also a large difference between the signal of a normal breast and a newly cancerous breast in the range of 6.6 GHz to 7 GHz such that the difference in frequency is 0.024 GHz, which is equal to 24 MHz the reflection coefficient for a newly cancerous breast is approximately equal to -80dB but for a clean breast it is approximately equal to -60 dB, as shown in Fig. 16(b).

Results of microwave imaging

A microwave imaging process relies on differences in the electrical properties of normal cells and tissues compared to newly infected cancer cells or tumors. A cancer cell’s electrical properties differ greatly from a normal cell, especially in the 8.5GHz range, which is why this frequency range was chosen. A normal breast phantom was taken in the first case, while a breast phantom with early-stage cancer was used in the second case. As shown in Fig. 17. it is possible to determine the tumor’s size and shape precisely.

The sensor was also used for three other cases, the first being a pure breast phantom. The second case is for a breast phantom with early-stage Non-invasive cancer, where the tumor radius is 5mm, located within the fibro-glandular. In this third case, there is more than one tumor on the breast phantom due to invasive cancer. There are two tumors in this case, the first of which is located within the Fibro-glandular, with a 5mm half-diameter. The second tumor, however, is partly in fibro-glandular tissue and partly in adipose tissue (fat). The distance between the two tumors is 25.9615 mm. The second tumor is 7 mm deeper than the first tumor. The half-diameter of the second tumor is smaller than that of the first tumor, equal to 3 mm. Fig. 18 illustrates the accuracy and good quality of the results.

Other experiments were conducted using the sensor, in which the angle between electric and magnetic fields was changed by 90 degrees. To achieve this, the sensor is rotated 90 degrees around itself, as shown in Fig. 14(c). The first case is a normal breast phantom. The second case is for a breast phantom with early-stage Non-invasive cancer, where the tumor radius is 5 mm, located within the fibro-glandular. The third case is for a breast phantom with invasive cancer with two tumors. The first is located within the Fibro-glandular, where the radius is 5 mm, and the second tumor is partly in the fibro-glandular and partly in the adipose tissue (fat). The distance between the two tumors equals 22 mm. In this case, the depth of both tumors is the same, but the radius of the second tumor is smaller than that of the first tumor, which is 3 mm. Fig. 19 illustrates the accuracy of the results.

The breast phantom’s complete microwave imaging system setup can be found in Fig 20, which highlights its design and various components. It consists of four antenna arrays; one transmits, and the other three receive scattered signals. The receivers are controlled by a 4-port RF converter system, a breast phantom suspension platform, and a laptop computer running MATLAB that processes the scattered signal data from the receiving antennas and reconstructs images of the various components of the breast phantom.

The antennas should be mounted on the top of a circular, clear ABS plastic container to rotate while scanning the breast phantom. A stepper motor with an SD02B controller should drive the plastic container. The breast phantom is positioned in the antenna array using the suspension platform during scanning; the configuration should be made such that there is always 2 cm between the installed antenna and the breast phantom. It is crucial to adjust the antenna angles to get outstanding scanning results and high-quality pictures; thus, the array can be rotated in polar coordinates from 0 to 180 degrees using the stepper motor. All antennas are linked to the RF switch using coaxial wires. Through port 1 of the VNA, microwave signals are generated and delivered to the breast phantom in the frequency domain designated for this scanning. The backscattered data (S\(_{21}\), S\(_{31}\), and S\(_{41}\)) are gathered using MATLAB software on a PC. The VNA (Agilent N5227A), the number of antennas, the number of scans, and the scanning angle of the antennas with the breast phantom affect the data quality.

With a gain of 10.51 dBi, the proposed sensor has the greatest directivity compared with earlier research. This unique finding significantly affects the outcome of breast cancer diagnoses, particularly in the early stages. Also, MWI imaging requires a high gain to ensure high image quality, minimal noise, and reliability for specialists. The size of the suggested sensor, when compared to the high gain, is quite modest, indicating the proposed sensor’s high performance. Also, specialists can use more sensors to get more data from more angles. This is important in enhancing the imaging process and building more confidence among specialists due to accurate and reliable results. As explained in Table 3,

Conclusions

A non-invasive sensor for screening breast cancer is presented in this paper. A few particularly important parameters in medical applications are discussed: reflection coefficient, gain, and radiation pattern. In addition, this paper presents Fidelity Factor (FF) and Group Delay results for both Face-to-Face and Side-by-Side scenarios. CST simulation results show that AMC can improve frequency selectivity by up to 9.35 dBi at 8.48 GHz, whereas measured results show 10.51 dBi. To validate the simulation results, the proposed antenna was fabricated. Results are presented for several cases, including the normal breast, a breast containing one non-invasive tumor, and a breast with two tumors of different sizes, locations, and depths. Finally, a detailed explanation of the results has been presented. Our AMC-based antenna array offers enhanced imaging capabilities for various cancers, including brain and lung tumors. Its compact design enables portable diagnostic devices, while its non-invasive nature supports continuous monitoring. This versatile technology can be integrated into multimodal systems and further developed with specialized phantoms, advancing medical imaging and diagnostics.

Data availability

The data needed to replicate the results are available within the article.

References

Harbeck, N. et. al., “Breast cancer,” Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 5, no. 66, (2019).

Waks, A. G. & Winer, E. P. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA 321, 288–300 (2019).

Siegal, R., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2012. Ca Cancer J Clin 64, 9–29 (2014).

Zerrad, F.E. et. al. “Multilayered metamaterials array antenna based on artificial magnetic conductor’s structure for the application diagnostic breast cancer detection with microwave imaging,” Med Eng Phys, vol. 99, no. 1037372022, (2022).

Mahmud, M. Z., Islam, M. T., Misran, N., Kibria, S. & Samsuzzaman, M. Microwave Imaging for Breast Tumor Detection Using Uniplanar AMC Based CPW-Fed Microstrip Antenna. IEEE Access 6, 44763–44775 (2018).

Islam, M.T., Mahmud, M.Z., Islam, M.T., Kibria, S., Samsuzzaman, M.: “A Low Cost and Portable Microwave Imaging System for Breast Tumor Detection Using UWB Directional Antenna array,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, no. 154912019, (2019).

Rao, P. K., Yadav, A. R. & Mishra, R. AMC-based antenna sensor for breast tumors detection. International Journal of Microwave and Wireless Technologies 13, 954–961 (2020).

Aldhaeebi, M.A., Alzoubi, K., Almoneef, T.S., Bamatraf, S.M., Attia, H., O M.R. Review of Microwaves Techniques for Breast Cancer Detection. Sensors (Basel) , 20. (2020)

Shaikh, K., Krishnan, S. & Thanki, R.M. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer early detection and diagnosis. Springer; (2021).

Alibakhshikenari, M. et al. Metamaterial-Inspired Antenna Array for Application in Microwave Breast Imaging Systems for Tumor Detection. IEEE Access 8, 174667–174678 (2020).

Hossain, K. et al. Negative Index Metamaterial-Based Frequency-Reconfigurable Textile CPW Antenna for Microwave Imaging of Breast Cancer. Sensors 22(4), 1626 (2022).

Hossain, A., Islam, M.T., Islam, M.T., Chowdhury, M.E.H., Rmili, H., Samsuzzaman, M. A Planar Ultrawideband Patch Antenna Array for Microwave Breast Tumor Detection. Materials (Basel) 13. (2020)

Hussein, M., Awwad, F., Jithin, D., El Hasasna, H., Athamneh, K., Iratni, R. Breast cancer cells exhibits specific dielectric signature in vitro using the open-ended coaxial probe technique from 200 MHz to 13.6 GHz. Sci Rep, 9:4681. (2019)

Dewan, R., Rahim, M.K.A., Hamid, M.R. et al. “Artificial magnetic conductor for various antenna applications: An overview,” Int J RF Microw Comput Aided Eng., 27:e21105, 2017.

Islam, M. T., Samsuzzaman, M., Faruque, M., Singh, M. J. & Islam, M. Microwave imaging based breast tumor detection using compact wide slotted UWB patch antenna. Optoelectron Adv Mater Rapid Commun 13, 448–457 (2019).

Kibria, S. et al. Breast phantom imaging using iteratively corrected coherence factor delay and sum. IEEE Access 7, 40822–40832 (2019).

Islam, M. T., Samsuzzaman, M., Islam, M. T., Kibria, S. & Singh, M. J. A homogeneous breast phantom measurement system with an improved modified microwave imaging antenna sensor. Sensors 18, 2962 (2018).

Samsuzzaman, M. et al. A 16-modified antipodal vivaldi antenna array for microwave-based breast tumor imaging applications. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 61(9), 2110–2118 (2019).

Islam, M. T., Mahmud, M. Z., Misran, N., Takada, J.-I. & Cho, M. Microwave breast phantom measurement system with compact side slotted directional antenna. IEEE access 5, 5321–5330 (2017).

Porter, E. et al. A wearable microwave antenna array for time-domain breast tumor screening. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 35, 1501–1509 (2016).

Zerrad, F.-E. et al. Microwave Imaging Approach for Breast Cancer Detection Using a Tapered Slot Antenna Loaded with Parasitic Components. Materials 16(4), 1496 (2023).

Hamza, M. N., Koziel, S. & Pietrenko-Dabrowska, A. “Design and experimental validation of a metamaterial-based sensor for microwave imaging in breast, lung, and brain cancer detection,” Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, (Jul. 2024).

Raza, A., Souza, M. I. O., Liaqat, M., Pepino, V. M., Borges, B. -H. V. “Ultra-wideband Patch Antenna with Inhomogeneous Artificial Magnetic Conductor and Nearly Constant Radiation Pattern for Breast Tumor Detection,” IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters, (2024).

Youssef, K., Abo-Zahhad, M., Kanaya, H., El-Malek, A. H. A. “A unified approach for breast cancer discrimination using metasurface-based microwave technology,” Discover Applied Sciences, vol. 6, no. 8, Jul. (2024).

Alibakhshikenari, M. et al. High performance antenna-on-chip inspired by SIW and metasurface technologies for THz band operation. Scientific Reports 13(1), 56 (2023).

Althuwayb, A. A. et al. Design technique to mitigate unwanted coupling in densely packed radiating elements of an antenna array for electronic devices and wireless communication systems operating in the millimeter-wave band. AEU-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 159, 154464 (2023).

Althuwayb, A. A. et al. Metasurface-inspired flexible wearable MIMO antenna array for wireless body area network applications and biomedical telemetry devices. IEEE Access 11, 1039–1056 (2022).

Alibakhshikenari, M. et al. Virtual antenna array for reduced energy per bit transmission at Sub-5 GHz mobile wireless communication systems. Alexandria Engineering Journal 71, 439–450 (2023).

Alibakhshikenari, M. et al. High gain/bandwidth off-chip antenna loaded with metamaterial unit-cell impedance matching circuit for sub-terahertz near-field electronic systems. Scientific Reports 12(1), 17893 (2022).

Collin, R.E. Field theory of guided waves. John Wiley & Sons; (1990).

Sievenpiper, D., Zhang, L., Broas, R. F., Alexopolous, N. G. & Yablonovitch, E. High-impedance electromagnetic surfaces with a forbidden frequency band. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and techniques 47, 2059–2074 (1999).

Ghosh, A., Kumar, V., Sen, G. & Das, S. Gain enhancement of triple-band patch antenna by using triple-band artificial magnetic conductor. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 12, 1400–1406 (2018).

Islam, M.T., Samsuzzaman, M., Islam, M.T., Kibria, S. & Singh, M.J. A Homogeneous Breast Phantom Measurement System with an Improved Modified Microwave Imaging Antenna Sensor. Sensors (Basel) (2018), 18.

Mahmud, M., Kibria, S., Samsuzzaman, M., Misran, N. & Islam, M. A new high performance hibiscus petal pattern monopole antenna for UWB applications. The Applied Computational Electromagnetics Society Journal (ACES) 2016:373-380.

Vorst, A.V., Rosen, A., Kotsuka, Y.:“RF/microwave interaction with biological tissues,” John Wiley & Sons, (2006).

Gabriel, C., Gabriel, S. & Corthout, Y. “The dielectric properties of biological tissues: I. Literature survey,” Physics in medicine & biology, vol. 41, no. 2231, (1996).

Land, D. & Campbell, A. “A quick accurate method for measuring the microwave dielectric properties of small tissue samples,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 37, no 183, (1992).

Cheng, Y. & Fu, M. Dielectric properties for non-invasive detection of normal, benign, and malignant breast tissues using microwave theories. Thorac Cancer 9, 459–465 (2018).

Nguyen, P. T., Abbosh, A. M. & Crozier, S. Thermo-Dielectric Breast Phantom for Experimental Studies of Microwave Hyperthermia. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters 15, 476–479 (2016).

Hamza, M.N. et. al. “Low-Cost Antenna-Array-Based Metamaterials for Non-Invasive Early-Stage Breast Tumor Detection in the Human Body,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 828, (2022).

Langtry, A. Understanding Cancer of the Breast (Irish Cancer Society, Dublin, Ireland, 2008).

Ullah, N. et al. Detection of breast tumor with a frequency selective surface loaded ultra-wide band antenna system. Physica Scripta 99(8), 085543 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Musa N.Hamza and Yadgar I. Abdulkarim conceived the experiments, Musa N.Hamza and Salah Raza Saeed, conducted the experiment(s), Muharrem Karaaslan and Fatih Ozkan Alkurt analysed the results, Musa N.Hamza and Fatih Ozkan Alkurt prepared the original draft, Bhargav Appasani and Rashid Mirzavand revised the original draft, Philibert Nsengiyumva supervised the entire project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The work does not involve any human or animal subjects

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamza, M.N., Abdulkarim, Y.I., Saeed, S.R. et al. Metamaterial-based Artificial magnetic conductor for efficient breast cancer diagnosis using a low-cost antenna array. Sci Rep 14, 28262 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79666-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79666-8