Abstract

We focused on the possibility that pathogenic microorganisms might produce immune suppressors to evade the action of immune cells. Based on this possibility, we have recently developed new co-culture method of pathogenic actinomyces and immune cells, however, the interaction mechanism between pathogens and cells was still unclear. In this report, co-culturing pathogenic fungi and immune cells were investigated. Pathogenic fungus Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899 and THP-1 cells were co-cultured and isolated a co-culture specific compound, butyrolactone Ia (1). 1 inhibits the production of nitric oxide by RAW264 cells and exhibits regulatory effects on autophagy, suggesting 1 plays a defensive role in the response of A. terreus IFM 65899 to immune cells. Furthermore, dialysis experiments and micrographs indicated that “physical interaction” between A. terreus IFM 65899 and THP-1 cells may be required for the production of 1. This is the first report of co-culture method of fungi with immune cells and its interaction mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Following the discovery of penicillin, the secondary metabolites produced by actinomycetes and fungi have significantly contributed to the advancement of innovative pharmaceuticals1, but the acquisition of such novel therapeutic compounds is challenging due to the recurrent isolation of known compounds2. Conversely, recent genomic analyses have elucidated that a significant portion of secondary metabolite-biosynthetic gene clusters (SM-BGCs) of actinomycetes and fungi typically remain silent under laboratory culture conditions3,4. For example, in Aspergillus species, which are among the most common fungi, more than 50% of the core backbone synthase enzymes for secondary metabolites are not linked to their predicted downstream products5. Thus, silent state genes must be activated for the production of novel natural products, which has prompted the development of various methods such as the optimization of culture conditions6, heterologous expression7, epigenetic regulation8, and ribosome engineering9. Co-culture is another effective strategy for activating silent SM-BGCs, as it mimics the microbial interactions found in natural environments10. This approach includes the co-culture of bacteria and fungi isolated from identical acidic mine drainages11, “combined-culture”, co-culturing of actinomycetes and mycolic-acid-containing bacteria12.

Our group recently approached the activation of silent SM-BGCs using the idea that pathogens might produce immune suppressors to evade the action of immune cells. We previously reported the isolation of new natural products13,14,15,16 and known compounds17 from the genus Nocardia cultured in the presence of animal cells, thus emulating the initial infection state. Recent detailed studies have illuminated strategies used by fungi to evade the host’s protective response, including the production of secondary metabolites such as mycotoxins with immunosuppressive activity18. For instance, gliotoxin has toxic effects on neutrophils, contributing to the virulence of A. fumigatus in non-neutropenic mice19. This finding suggests the potential for both actinomycetes and fungi to produce novel immune suppressors, allowing them to adapt to the host environment.

In this study, we developed the co-culture method for activating the production of secondary metabolites by fungi. We also searched for novel natural products by co-culturing immune cells and pathogenic fungi isolated from clinical specimens. We describe the isolation of butyrolactone Ia (1) as a co-culture specific compound (Fig. 1). 1 was obtained from a co-culture of the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899 with THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cells. Additionally, we investigated the bioactivity of the isolated compound and elucidated the mechanism underlying its production.

Results and discussion

Aspergillus species are widespread in the environment, but some of them such as A. flavus, A. fumigatus, A. nidulans, A. niger and A. terreus may lead to Aspergillosis as a variety of allergic reactions and infectious diseases in primarily immunocompromised individuals20. For example, A. fumigatus is the most common fungus causing aspergillosis21,22. A. terreus is resistant to amphotericin B in vitro and in vivo23, and invasive aspergillosis caused by A. terreus displayed a poor outcome and high mortality24. In addition, Paecilomyces sp. are emerging pathogens that causes severe human infections, including devastating oculomycosis25. Scedosporium sp. are known as a cause of Scedosporiosis as fungal infections26. We have been interested in the interaction of these pathogenic fungi and immune cells for activation of compounds production. Therefore, we started to examine the possibility of co-culture of fungi and immune cells.

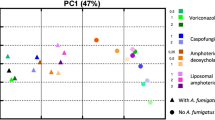

Eighteen strains of 14 pathogenic fungi such as Aspergillus, Paecilomyces and Scedosporium were co-cultured with THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cells (Table 1). This cell line served as a model of human monocytes. Each fungal strain and THP-1 were co-cultured in the same vessel at 28 °C, using Czapek-Dox (CD) medium, under static conditions for either 1 or 2 weeks. The culture extracts were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and compared with extracts obtained from fungal monocultures to find natural products specifically produced in the presence of THP-1 cells. A co-culture-specific compound was detected during the co-culture of Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899 and THP-1 (Fig. 2). The ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extract obtained from a large-scale co-culture of these strains was fractionated using silica gel column chromatography and purified by reverse-phase HPLC to isolate compound 1.

HPLC analyses of cultures; (upper) THP cells only, (middle) A. terreus IFM 65899 only, (bottom) co-culture of A. terreus IFM 65899 and THP cells; Co-culture of A. terreus IFM 65899 and THP-1 cells was performed in 75 cm2 flask, at a cell number ratio as THP-1 : fungi = 1.25 × 107 cells : 0.3 cm3. Flasks were incubated in CD medium at 28 °C under static conditions for 2 weeks in atmospheric air (see “Methods” for detail co-culture method and cultural conditions).

Workup of the extract provided compound 1 as a brown powder. Its molecular formula C23H22O7 was determined by trapped-ion-mobility spectrometry coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TIMS-TOF MS), (observed m/z 409.1292 [M-H]-, calculated for C23H21O7 409.1293), indicating 13 degrees of unsaturation. The IR spectrum showed broad and intense absorption bands corresponding to hydroxy (3340 cm− 1) and carbonyl (1734 cm− 1) groups, respectively. The 13C NMR/HMQC spectra of 1 revealed 23 carbon signals, including two carbonyls (C1/C6), two sp2 oxygenated carbons (C4’/C4’’) of phenolic systems, along with six quaternary carbons (C2/C3/C1’/C1’’/C3’’/C9’’), eight sp2 methine signals (C2’/C3’/C5’/C6’/C2’’/C5’’/C6’’/C8’’), a quaternary oxygenated methine (C4), two methylenes (C5/C7’’) and two methyls (C10’’/C11’’) (Table 2).

The1H NMR spectrum in DMSO-d6 showed signals for a 1H olefinic methine (δH 5.00) and a 2H methylene (δH 2.99). The presence of a dimethylallyl group was supported by COSY correlations between the methylene H7’’ (δH 2.99) with olefinic methine H8’’ (δH 5.00) protons, and HMBC correlations from H-11’’ to C8’’/C9’’/C10’’, and from H7’’ to C8’’ (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the NOESY correlation between H11’’ with C8’’ indicated the cis-position of C11’’ (Figure S11). Three signals at δH 6.51 (1H, d, J = 8.2 Hz), δH 6.47 (1H, dd, J = 8.2, 1.9 Hz) and δH 6.36 (1H, d, J = 1.9 Hz) suggested the presence of a trisubstituted phenyl group. HMBC correlations from H7’’ to C2’’/C3’’/C4’’ revealed that the trisubstituted phenyl group is linked to the dimethylallyl group at the C3’’ position, and HMBC correlations from 4’’-OH to C3’’/C4’’/C5’’ indicated a hydroxy group at the C4’’ position. Additionally, two signals at δH 7.57 (2H, d, J = 8.9 Hz) and δH 6.87 (2H, d, J = 8.9 Hz) indicated a para-disubstituted phenyl group, and HMBC correlations from 4’-OH to C3’/C4’/C5’ confirmed a hydroxy group at the C4’ position. Furthermore, HMBC correlations were observed from 2-OH to a carbonyl (C1) and a quaternary carbon (C2), from H5/H2’/2-OH to a sp2 quaternary carbon (C3), and from H5 to a sp3 quaternary oxygenated carbon (C4). These correlations suggested that compound 1 has a butyrolactone skeleton. Two doublet signals (δH 3.29, 3.34, J = 14.8 Hz) represent a methylene. These partial structures were fully connected by the following HMBC correlations: H5-C3/C4/C1’’/C2’’/C6’’, and H2’-C3. Finally, the substituent linked to position C4 was determined to be a carboxyl group based on the remaining molecular weight and the presence of a carbonyl. HMBC corrections from H5 to C6 were also observed. Thus, the structure of compound 1 was established.

The absolute configuration was determined by comparing the experimental ECD spectrum of 1 with the spectra calculated for (R) and (S)-1. The CD spectrum of 1 exhibited cotton effects similar to those for (R)-1 (Fig. 4a). In addition, the following experimental NOESY correlations in methanol-d4 supported the relative configuration of the global minimum structure of (R)-1 computed by density functional theory (DFT) calculation: H5 (δH 3.36)-H6’’, H5 (δH 3.44)-H2’/H2’’/H6’’, H2’’-H6’/H8’’, H7’’-H10’’, and H8’’-H11’’ (Fig. 4b). Hence, it was concluded that 1 adopts the (R)-configuration. Although compound 1 was reported as an organic synthetic compound27,28, and detected by only ESI-MS as a natural product29, the isolation and structure determination of 1 is described for the first time in this report. We therefore named 1 butyrolactone Ia, based on butyrolactone I30.

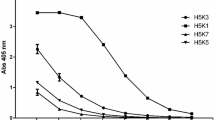

Infection by pathogenic microorganisms triggers the host’s innate and adaptive immune responses. Recent study of the interaction of human lung epithelial cells (A549) with A. terreus revealed that immune responses such as NF-kB signaling were activated31. In innate immunity, phagocytosis of the fungus is initiated when macrophage pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) recognize the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present on the fungal cell surface32. We therefore hypothesized that the pathogenic fungus A. terreus IFM 65899 might produce butyrolactone Ia (1) as an immune suppressor to overcome attack by immune cells. Therefore we analyzed the anti-inflammatory activity of compound 1 against immune cells. The production rate of nitric oxide (NO), an inflammatory mediator, was assessed using the mouse macrophage-like cell line RAW264 treated with 0.01 µg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to stimulate Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) as a PRR33. LPS-induced NO production was inhibited in the presence of 20 µM BOT-64, a known NF-κB inhibitor34. In the same assay, 1 inhibited NO production, with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 18 µM (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, 1 suppressed LPS-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) at the protein (Fig. 5b) and mRNA levels (Figure S4a). The expression of IL-1β mRNA as inflammatory cytokine was also suppressed (Figure S4b).

Inhibitory activity of nitric oxide (NO) production by 1 against RAW264 cells. (a) NO production rate. The vertical axis shows the relative amount of NO compared to the control, whose level was set at 1. (b) Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Original blots are presented in Supplementary Figs. S13 and 14.

We evaluated additional bioactivities of compound 1 using cellular morphology and phenotypic screening systems, such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) regulation, autophagy regulation, wound healing inhibition, and neuroprotection. We found that 1 exhibited regulatory effects on autophagy, as determined by monitoring fluorescence signals in HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3. LC3 serves as an autophagy marker as autophagy progresses. However, the level of LC3 at a given time point does not necessarily reflect the degree of autophagic activity, as both autophagy activation and the inhibition of autophagosome degradation markedly increase LC3 levels35. Our observation implies that the augmentation of puncta in GFP-LC3/HeLa cells treated with 1 results from the action of either an autophagy inducer such as rapamycin or an inhibitor of autolysosome formation such as bafilomycin A1. In the absence of treatment, GFP-LC3 predominantly exhibited diffuse green fluorescence in the cytoplasm. However, characteristic punctate fluorescent patterns of GFP-LC3 were observed in the presence of 10 µM butyrolactone Ia (1), whereas such patterns were absent upon the addition of 1 µM 1 (Fig. 6). These observations suggest that 1 acts either as an inducer or inhibitor of autophagy, although currently it is not possible to distinguish between these two possibilities. As an evolutionary counterpoint, intracellular pathogens have evolved mechanisms to obstruct autophagic microbicidal defenses and to manipulate host autophagic responses for their own survival or proliferation. Conversely, eukaryotic pathogens can deploy their own autophagic machinery36. Thus, A. terreus IFM 65899 may produce 1 to deter immune cell activity. Indeed, 3-benzyl-5-((2-nitrophenoxy)methyl)-dihydrofuran-2(3H)-one (3BDO), a butyrolactone derivative, inhibits LPS-induced autophagy in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)37. Although there is a possibility that compound 1 was produced for other purposes such as microbial communication or quorum sensing, these previous reports and current results suggest that compound 1 might be a defensive compound in response to immune cells.

Subsequently, we attempted to elucidate the underlying mechanism governing the production of compound 1. Given the phagocytosis of pathogenic microorganisms by innate immune cells such as macrophages, physical interaction with immune cells may be necessary for the production of butyrolactone Ia (1) as a defensive compound against immune cells. The micrograph obtained of the co-culture confirmed the intricate intertwining of fungi with immune cells (Fig. 7a). We therefore conducted a co-culture experiment in which fungi and immune cells were separated by a dialysis membrane with a pore size of 0.03 μm. No production of 1 was observed (Fig. 7b). To exclude the possible involvement of signal molecules incapable of traversing the membrane, a cell culture medium in which THP-1 cells had been cultured in CD medium for 2 weeks was filtered and separated into supernatant and cellular fractions. Each fraction was added to the fungi and cultured for 2 weeks. 1 was produced following the addition of cellular fractions to the fungi but it was not produced upon the addition of supernatant fractions (Fig. 7c).

However, the significance of cell viability remained unclear, as THP-1 cells cultured in CD medium for 2 weeks retained their structural integrity but exhibited decreased viability. On the other hand, 1 was not produced when the immune cells were disrupted by sonication (Fig. 7d), or when RIPA buffer (Figure S5) was subsequently added to the fungi. This suggests that maintaining the immune cell structure is crucial for the specific response of the fungi, indicating that “physical interaction” with THP-1 cells may be required for the production of 1. Several previous reports suggest that physical interaction, such as between bacteria and fungal mycelia38, and between actinomycetes and mycolic-acid-containing bacteria39, are required for activating the production of secondary metabolites. These reports support our proposal that physical interaction with THP-1 cells is necessary for the production of 1.

Physical interaction may be required for production of 1. (a) Micrographs obtained from single or co-culture after 2 days; right; illustration of image of co-culture. (b) dialysis experiments (c) addition of cell culture supernatant (d) disruption of immune cell structure by sonication. Co-culture was performed for (b) 1 week and (c), (d) 2 weeks, respectively (see “Methods” for detail experimental methods and cultural conditions).

Conclusion

Here, we described development of co-culture method of pathogenic fungi and immune cells. Co-culture of the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899 with THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cells gave butyrolactone Ia (1) as a co-culture specific compound. In addition, we discovered immunosuppressive activities of compound 1: that it is an inhibitor of NO production and exhibits regulatory effects on autophagy, suggesting it plays a defensive role in the response of A. terreus IFM 65899 to immune cells. Furthermore, 1 was not produced when the immune cells were separated from the pathogenic fungus by a dialysis membrane, indicating that “physical interaction” with THP-1 cells may be required for the production of 1. Compound 1 was not produced when the immune cell structure was disrupted by sonication and the disrupted cells were subsequently added to fungi, indicating that an intact immune cell structure might be necessary for fungi to produce compound 1. In this report, we described the potential of co-culture method of fungi with immune cells for activation of the compound production.

Methods

General experimental procedures

The following instruments were used in this study: a P-1020 polarimeter (JASCO) for optical rotations, a J-1100 CD spectrometer (JASCO) for circular dichroism, a U-5100 spectrophotometer (Hitachi) for UV-Visible spectra, a FT-IR ALPHA spectrometer (Bruker) for infrared spectroscopy, a timsTOF mass spectrometer (Bruker) for trapped-ion-mobility spectrometry coupled to time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TIMS-TOF MS) spectra, a D-2000 system (Hitachi) for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), a JNM-ECA500 spectrometer (JEOL) for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra. Solvent chemical shifts of NMR spectra (δH 2.50, δC 39.52 for DMSO-d6; δH 3.31, δC 49.00 for methanol-d4) were used as the internal standard. The following adsorbents were used for purification: Silica Gel 60 N (Kanto Chemical) for flash silica gel column chromatography and CAPCELL PAK C18 MGII (ϕ 20 × 250 mm, Osaka Soda) for preparative HPLC.

Cell culture

Human THP-1 cells were obtained from JCRB and cultured in RPMI-1640 (FUJIFILM Wako) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, gibco). Mouse macrophage-like cell line RAW264 was obtained from RIKEN BioResource Research Center and cultured in D-MEM (High Glucose, FUJIFILM Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS. Cultures were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in 5% CO2 /95% air.

Fungal strain

The pathogenic fungal strains used in this study were isolated from clinical specimens, obtained from Medical Mycology Research Center, Chiba University, through the National Bio-Resource Project, Japan (Table S1).

Co-culture method

-

1.

Seed culture of fungal strains for a co-culture in Czapek–Dox medium. The number of fungal spores was counted under a microscope using a cell counter plate (Watson Co., Ltd.). Fungal spores (1 × 106 spores/mL) were added to 50 mL of PD liquid medium containing potato dextrose broth (PD) (2.4 g/100 mL) in a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask along with eight glass beads (BZ-5, As One Corp.). The flask was incubated at 28 °C for 5 days with shaking at 160 rpm. Each fungal strain was cultivated in 25 mL of PD medium containing of BD Difco™ Potato Dextrose Broth (2.4 g/100 mL, Becton, Dickinson and Company) in a 50 mL erlenmeyer flask at 28 °C for 5 days with shaking (160 rpm). After cultivation, the culture broth was added to a 50 mL tube and the supernatant was removed after centrifugation at 3500 rpm at 20 °C for 5 min. 10 mL of Czapek-Dox (CD) medium consisting of sucrose (3 g/100 mL, Wako), NaNO3 (0.3 g/100 mL, Wako), K2HPO4 (0.1 g/100 mL, Kanto Chemical), KCl (0.05 g/100 mL, Nacalai Tesque), MgSO4·7H2O (0.05 g/100 mL, Nacalai Tesque), and FeSO4·7H2O (0.001 g/100 mL, Wako) was added to the tube and the supernatant was removed after centrifugation. These procedures were repeated, and the fungal volume was measured using a glass stoppered test tube with osmotic baking scale.

-

2.

Co-culture in CD medium in a cell culture flask. THP-1 cells cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS were collected to 50 mL tubes. The supernatant was removed after centrifugation at 3500 rpm at 20 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, THP-1 cells (5.0 × 105 cells/1 mL) in 25 mL of CD medium was added to a 75 cm2 cell culture flask (Violamo). A suspension of fungi was added to the flask until the cell number ratio was reached (THP-1 : fungi = 1.25 × 107 cells : 0.3 cm3). We examined the ratio of cells and fungi. It was revealed that 0.3 cm3 of fungi showed several co-culture specific peaks. Flasks were incubated at 28 °C under static conditions for 2 weeks in atmospheric air. The media changes were not carried out during the incubation period.

-

3.

Detection of co-culture specific compounds by HPLC. After co-cultivation for 2 weeks, the culture broth was separated into the supernatant and mycelial cake. The mycelial cake was extracted with MeOH. The MeOH extract was combined with the supernatant obtained above and partitioned with EtOAc and water (repeated 3 times). The EtOAc extracts of these culture broths were analyzed by HPLC under the following conditions: 15–85% MeCN/H2O in 0.1% HCOOH, for 60 min, with a linear gradient, and 100% MeCN, isocratic for 15 min; flow rate: 0.7 mL/min; UV detection: diode array (200–600 nm); column: a CAPCELL PAK C18 MGII (ϕ 4.6 × 250 mm). The same procedures were performed for the flasks cultivated cells or fungi alone.

1)

Fermentation and isolation

The strain Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899 was cultured at 28 °C under static conditions for 2 weeks in atmospheric air in 60 mL CD medium in 175 cm2 cell culture flasks (Violamo) × 54 in the presence of THP-1 (cell number ratio THP-1: A. terreus IFM 65899 = 3.0 × 107 cells: 0.72 cm3). After co-cultivation for 2 weeks, the culture broth (3.2 L) was separated the supernatant and mycelium cake. The mycelial cake was extracted using MeOH (3.2 L). The MeOH extract and the supernatant were combined and partitioned between EtOAc (3.2 L × 2) and water to obtain the EtOAc extract (1.14 g). The EtOAc extract was subjected to silica gel column chromatography (Hexane : EtOAc = 7:3, 6:4, 5:5, 4:6, 3:7, 0:1, CHCl3: MeOH = 100:0, 100:10, 100:30, 1-BuOH : MeOH: H2O = 4:1:1) to produce 10 fractions (1a-1j). Fraction 1f (34.3 mg), 1 g (11.2 mg), 1i (178.7 mg) were subjected to preparative reversed-phase HPLC (40% MeCN, including 0.1% HCOOH, isocratic for 35 min (Fr. 1f, 1 g) or 60% MeOH, including 0.1% HCOOH, isocratic for 35 min (Fr. 1i); flow rate 8.0 mL/min; UV detection at 290 nm; column: CAPCELL PAK C18 MGII, ϕ 20 × 250 mm) and isolate butyrolactone Ia (11.4 mg).

Butyrolactone Ia (1): brown powder; +45.2 (c 0.27, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 204 (4.46), 228 (4.12), 306 (4.20) nm; IR (ATR) νmax 3340, 2922, 1734, 1609, 1517, 1438, 1385, 1262, 1181, 1057, 838, 446 cm− 1; CD (MeOH) λmax 205.5 (24.86), 230.5 (− 5.87), 253.5 (4.81), 281.5 (− 2.58), 311.0 (2.93) nm;1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 2; TIMS-TOF MS m/z 409.1292 [M−H]− (calcd for C23H21O7, 409.1293).

ECD calculations of 1

Conformational sampling of structure (R)-1 was performed by applying 100,000 steps of the Monte Carlo Multiple Minimum method with the OPLS4 force field to afford 204 conformational isomers within 5.0 kcal/mol from the minimum energy conformer. The geometries were then optimized at the M06-2X/6-31G(d) level of theory with the SMD solvation model (MeOH). Frequency calculations were carried out at the same level of theory to confirm the absence of imaginary frequencies and obtain thermal corrections to the Gibbs free energies. After eliminating identical structures, the energy evaluation of the geometries at the M06-2X/6-311 + G(d, p)/SMD(MeOH) level of theory provided 65 low-lying conformers within 2.5 kcal/mol from the minimum Gibbs free energy. The ECD was simulated by the TD-DFT calculation of 25 excited states at the ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP-IEFPCM (MeOH) level of theory. The spectrum of (R)-1 was created by the weighted average of the above-obtained spectra (half-width: 0.24 eV) according to the Boltzmann distribution, with UV correction and scaling the vertical axis to adjust the intensity. The ECD spectrum of (S)-1 was similarly simulated using 201 OPLS4 eminimized structures and 67 DFT optimized low-lying conformers, respectively.

Cell viability assay of THP-1 in CD medium

THP-1 (1.0 × 104 cells/100 µL/well) were seeded into 96 well black microplates in 100 µL of the CD medium and incubated at 28 °C in atmospheric air. CD medium was used after filtration by 0.20 μm hydrophobic polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) membrane (Merck Millipore). After AlamarBlue reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was added (10 µl per well), the plate was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 at which point the fluorescence intensity (excitation and emission at 545 and 590 nm, respectively) was measured using a SpectraMax i3x microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Cell viability assay of RAW264

Cell viability was measured by using the fluorescence micro-culture cytotoxicity assay, which has been described previously40. RAW264 (3.0 × 104 cells/100 µL/well) were seeded into 96 well black microplates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the medium was removed and replaced with 90 µL of the sample containing D-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After incubation for 2 h, 10 µL lipopolysaccharide (LPS from E. coli O26, FUJIFILM Wako) was added to stimulate the cells for 24 h (final concentration of LPS, 0.01 µg/mL). The culture supernatant (50 µL) was transferred to a clear 96-well plate and used for the nitric oxide (NO) production assay (see below). The remaining spent medium in the original plate was removed and supplemented with 100 µL per well of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 µg/mL fluorescein diacetate (FUJIFILM Wako). This plate was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C at which point the fluorescence intensity (excitation and emission at 494 and 521 nm, respectively) was measured using a SpectraMax i3x microplate reader.

NO production assay

The NO production in spent medium was measured using the Griess reaction41. 50 µL of griess reagent consisting of 1% sulfanilamide (FUJIFILM Wako) and 0.1% N-1-Napthyl ethylenediamine Dihydrochloride (FUJIFILM Wako), 2.5% Phosphoric Acid (Wako) was distributed to the above a clear 96-well plate containing 50 µL of the culture supernatant. The resulting mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, shielded from light. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a SpectraMax i3x microplate reader. NO assays were performed in triplicate. BOT-64 (Abcam)34 was used as the positive control.

Western blot analysis

RAW 264 cells (3.0 × 105 cells/1 mL/well) were seeded into 12 well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation of the samples containing medium for 2 h, LPS was added to stimulate cells for 12 h (final concentration, 0.01 µg/mL). Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS and collected by centrifugation. Whole cell lysates were then prepared with RIPA buffer containing of 25 mM HEPES, 1.5% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4 (pH 7.8) and supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). Lysates were subjected for electrophoresis on 8% or 10% polyacrylamide gels under reduced and denatured condition. Then proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore). After blocking of the membrane with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) at room temperature for 30 min, the blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies; anti-iNOS (ab15323, abcam) at 1:250 (XL-Enhancer Solution 1st; APRO Science), 30 min at room temperature with primary antibodies; anti-β-actin (#A2228, Sigma Aldrich) at 1:5000 in TBS containing 0.1% sodium azide. β-actin was used as an internal control. After washing with TBS-T, the membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies; anti-rabbit IgG (#7074S, Cell Signaling) at 1:5000 (iNOS: 3% skim milk in TBS-T), or anti-mouse IgG (#NA931, GE Healthcare) at 1:5000 (β-actin: 3% skim milk in TBS-T). After washing of the blots with TBS-T, chemiluminescence was detected using Immobilon reagent (Merck Millipore) on ChemiDoc™ XRS + system (Bio-Rad).

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

RAW 264 cells (3.0 × 105 cells/1 mL/well) were seeded into 12 well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation of the samples containing medium for 2 h, LPS was added to stimulate cells for 24 h (final concentration, 0.01 µg/mL). Then the total RNA was purified from the RAW264 cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following a manufacturer’s instruction. Extracted RNA was immediately reverse-transcribed to cDNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (RNase H Minus, Point Mutant) (Promega) and dNTP Mixture (Takara Bio) with oligo dT primers. qPCR was then performed on LightCycler 96 system (Roche Diagnostics) using THUNDERBIRD Next SYBR™ qPCR Mix (TOYOBO). The primers and thermal cycling program were designed as Table S2. Relative mRNA abundances were evaluated by ΔΔCt method using β-actin as an internal control.

Autophagy regulation assay

Autophagy regulation assay was performed according to a previously described method42. In this system, GFP-LC3/HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 as autophagy marker (by degradation during the progression of autophagy) were used to evaluate autophagy regulation activity by monitoring GFP-LC3 fluorescence signals. After treated with the samples for 24 h, the puncta of GFP-LC3 are observed under a fluorescence microscope. Rapamycin (10 µM) as a known autophagy inducer or bafilomycin A1 (10 nM) as a known inhibitor of autolysosome formation were used as the positive control.

Experiments elucidating the production mechanism of 1

-

1.

Dialysis experiments. THP-1 cells and A. terreus IFM 65899 were pre-cultured and replaced them in CD medium using the above-mentioned method. A suspension of cells or fungi in 1.4 mL CD medium was added to each container of UniWells™ Horizontal Co-Culture Plate (Ginrei lab) until the cell number ratio was reached (THP-1: fungi = 7.5 × 105 cells : 0.018 cm3) and they were separated by a dialysis membrane with pore size 0.03 μm (Ginrei lab). Co-culture plates were incubated at 28 °C for 1 week.

-

2.

Addition of the supernatant of cell culture medium. THP-1 cells cultivated in CD medium for 2 weeks in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask. After the cultivation, they were collected to 50 mL tubes and centrifuged at 3500 rpm at 20 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.20 μm hydrophobic polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) membrane (Merck Millipore) for cell removal, using as supernatant fraction. The precipitation after centrifugation was dissolved in 25 mL of CD medium, using as cellular fraction. Each fraction and fungi were added to a flask and cultured at 28 °C for 2 weeks.

-

3.

The disruption of cell structure by sonication. THP-1 cells (1.25 × 107 cells/75 cm2 flask) were dissolved 1mL CD medium and sonicated. These lysates were separated into the supernatant and precipitate by centrifugation of 10000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min and the precipitate was dissolved in 1 mL CD medium. Each fraction and fungi were added to a flask and cultured at 28 °C for 2 weeks.

-

4.

The disruption of cell structure by RIPA buffer. THP-1 cells (1.25 × 107 cells/75 cm2 flask) were dissolved 250 µL RIPA buffer and sonicated. These lysates were separated into the supernatant and precipitate by centrifugation of 10000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min and the precipitate was dissolved in 1 mL CD medium. Each fraction and fungi were added to a flask and cultured at 28 °C for 2 weeks.

1)

Data availability

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its Supporting Information.

References

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 770–803 (2020).

Li, J. W. & Vederas, J. C. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless Frontier? Science. 325, 161–165 (2009).

Nett, M., Ikeda, H. & Moore, B. S. Genomic basis for natural product biosynthetic diversity in the actinomycetes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 1362–1384 (2009).

Keller, N. P., Turner, G. & Bennett, J. W. Fungal secondary metabolism—from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 937–947 (2005).

Romsdahl, J. & Wang, C. C. Recent advances in the genome mining of Aspergillus secondary metabolites (Covering 2012–2018). MedChemComm 10, 840–866 (2019).

Bode, H. B., Bethe, B., Höfs, R. & Zeeck, A. Big effects from small changes: Possible ways to explore nature’s chemical diversity. ChemBioChem 3, 619–627 (2002).

Huo, L. et al. Heterologous expression of bacterial natural product biosynthetic pathways. Nat. Prod. Rep. 36, 1412–1436 (2019).

Williams, R. B., Henrikson, J. C., Hoover, A. R., Lee, A. E. & Cichewicz, R. H. Epigenetic remodeling of the fungal secondary metabolome. Org. Biomol. Chem. 6, 1895–1897 (2008).

Shima, J., Hesketh, A., Okamoto, S., Kawamoto, S. & Ochi, K. Induction of actinorhodin production by RpsL (encoding ribosomal protein S12) mutations that confer streptomycin resistance in Streptomyces lividans and Streptomyces Coelicolor A3(2). J. Bacteriol. 178, 7276–7284 (1996).

Bertrand, S. et al. Metabolite induction via microorganism co-culture: a potential way to enhance chemical diversity for drug discovery. Biotechnol. Adv. 32, 1180–1204 (2014).

Park, H. B., Kwon, H. C., Lee, C. H. & Yang, H. O. Glionitrin A, an antibiotic-antitumor metabolite derived from competitive interaction between abandoned mine microbes. J. Nat. Prod. 72, 248–252 (2009).

Onaka, H., Mori, Y., Igarashi, Y. & Furumai, T. Mycolic acid-containing bacteria induce natural-product biosynthesis in Streptomyces species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 400–406 (2011).

Hara, Y. et al. Coculture of a pathogenic actinomycete and animal cells to produce nocarjamide, a cyclic nonapeptide with wnt signal-activating effect. Org. Lett. 20, 5831–5834 (2018).

Hara, Y. et al. Dehydropropylpantothenamide isolated by a co-culture of Nocardia tenerifensis IFM 10554T in the presence of animal cells. J. Nat. Med. 72, 280–289 (2018).

Hara, Y. et al. Two bioactive compounds, uniformides A and B, isolated from a culture of Nocardia uniformis IFM0856T in the presence of animal cells. Org. Lett. 24, 4998–5002 (2022).

Hara, Y. et al. Corrrection to two bioactive compounds, uniformides A and B, isolated from a culture of Nocardia uniformis IFM0856T in the presence of animal cells. Org. Lett. 24, 5867 (2022).

Hara, Y. et al. Isolation of peptidolipin NA derivatives from the culture of Nocardia arthritidis IFM10035T in the presence of mouse macrophage cells. Heterocycles. 104, 185–190 (2021).

Arias, M. et al. Preparations for invasion: modulation of host lung immunity during pulmonary aspergillosis by gliotoxin and other fungal secondary metabolites. Front. Immunol. 9, 2549 (2018).

Spikes, S. et al. Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus Fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 479–486 (2008).

Paulussen, C. et al. Ecology of aspergillosis: insights into the pathogenic potency of Aspergillus fumigatus and some other Aspergillus Species. Microb. Biotechnol. 10, 296–322 (2017).

Denning, D. W. Invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 781–803 (1998).

Latgé, J. P. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 310–350 (1999).

Walsh, T. J. et al. Experimental pulmonary aspergillosis due to aspergillus terreus: Pathogenesis and treatment of an emerging fungal pathogen resistant to amphotericin B. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 305–319 (2003).

Hachem, R. et al. Invasive aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus terreus: an emerging opportunistic infection with poor outcome independent of azole therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69, 3148–3155 (2014).

Pastor, F. J. & Guarro, J. Clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome of Paecilomyces lilacinus infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12, 948–960 (2006).

Cortez, K. J. et al. Infections caused by Scedosporium spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 157–197 (2008).

Morishima, H. et al. Preparation, antitumor activity, and formulations of dihydrofuran compounds. Jpn. Kokai Tokkyo Koho JP. 6100445 (1994).

Rathore, D., Jani, D. & Nagarkatti, R. Novel Therapeutic Target for Protozoal Diseases. U. S. Patent US20070148185 (2007).

Tilvi, S., Parvatkar, R., Awashank, A. & Khan, S. Investigation of secondary metabolites from marine-derived fungi Aspergillus. ChemistrySelect 7, e202203742 (2022).

Kiriyama, N., Nitta, K., Sakaguchi, Y., Taguchi, Y. & Yamamoto, Y. Studies on the metabolic products of Aspergillus terreus. III. Metabolites of the strain IFO 8835. (1). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 25, 2593–2601 (1977).

Thakur, R. & Shankar, J. Proteome analysis revealed Jak/Stat signaling and cytoskeleton rearrangement proteins in human lung epithelial cells during Interaction with Aspergillus Terreus. Curr. Sig Trans. Ther. 14, 55–67 (2019).

Erwig, L. P. & Gow, N. A. Interactions of fungal pathogens with phagocytes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 163–176 (2016).

Vasselon, T. & Detmers, P. A. Toll receptors: a central element in Innate Immune responses. Infect. Immun. 70, 1033–1041 (2002).

Kim, B. H. et al. Benzoxathiole derivative blocks lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor-κB activation and nuclear factor-κB-regulated gene transcription through inactivating inhibitory κB kinase β. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1309–1318 (2008).

Yoshii, S. R. & Mizushima, N. Monitoring and measuring autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1865 (2017).

Deretic, V., Levine, B. & Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell. Host Microbe. 5, 527–549 (2009).

Meng, N. et al. A butyrolactone derivative suppressed lipopolysaccharide-induced autophagic injury through inhibiting the autoregulatory loop of p8 and p53 in vascular endothelial cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 44, 311–319 (2012).

Schroeckh, V. et al. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 14558–14563 (2009).

Asamizu, S., Ozaki, T., Teramoto, K., Satoh, K. & Onaka, H. Killing of Mycolic acid-containing bacteria aborted induction of antibiotic production by Streptomyces in combined-culture. PLoS One. 10, e0142372 (2015).

Lindhagen, E., Nygren, P. & Larsson, R. The fluorometric microculture cytotoxicity assay. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1364–1369 (2008).

Griess, P. Bemerkungen zu Der Abhandlung Der HH. Weselsky Und Benedikt „Ueber Einige Azoverbindungen. Ber Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 12, 426–428 (1879).

Sasazawa, Y. et al. Xanthohumol impairs autophagosome maturation through direct inhibition of valosin-containing protein. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 892–900 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Molecular Profiling Committee, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Advanced Animal Model Support (AdAMS)” from the MEXT, Japan (KAKENHI 22H04922), for evaluating cell morphology and phenotypic screening systems. This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Area (A) “Latent Chemical Space” (23H04880 [M.A.A.] and 23H04884 [M.A.A.]) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, and the Mitsubishi Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.A., S.S. and Y.U., designed most aspects of this study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. Y.U. performed the study biological experiments. K.F. and D.U. calculated the ECD spectrum of 1. T.Y. provided the fungal strains and support regarding the culture of strains. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ujie, Y., Saito, S., Fukaya, K. et al. Aspergillus terreus IFM 65899-THP-1 cells interaction triggers production of the natural product butyrolactone Ia, an immune suppressive compound. Sci Rep 14, 28278 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79837-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79837-7