Abstract

This study investigates the impact of industrial wastewater from leather, household, and marble sources on the growth, physiological traits, and biochemical responses of Momordica charantia (bitter melon). Industrial activities often lead to the release of contaminated effluents, which can significantly affect plant health and agricultural productivity. Water analysis revealed that leather effluent contained high concentrations of heavy metals, including cadmium (2.67 mg/L), lead (1.95 mg/L), and nickel (1.02 mg/L), all of which exceeded the recommended safety limits for irrigation. Seed germination was significantly reduced, with only 45% germination in seeds irrigated with leather effluent, compared to 90% in the control group. Similarly, in plants treated with leather wastewater, shoot length, and root length were reduced by 38% and 42%. Chlorophyll content showed a marked decline, with chlorophyll “a” reduced by 25% and chlorophyll “b” by 30% in wastewater-treated plants, indicating impaired photosynthetic activity. Antioxidant enzyme activity, including catalase and superoxide dismutase, increased by up to 40%, reflecting a stress response to heavy metal toxicity. These findings highlight that industrial wastewater severely disrupts plant metabolic processes, leading to stunted growth and physiological stress. To safeguard crop productivity and food security, stringent wastewater treatment protocols must be implemented to mitigate environmental contamination. Future research should focus on developing advanced remediation techniques and sustainable wastewater management practices to reduce heavy metal toxicity and enhance soil health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Momordica charantia L., commonly known as bitter melon or bitter gourd, belongs to Cucurbitaceae family and is predominantly found in tropical and subtropical regions. The entire plant, including its fruit, is distinctly bitter in flavor. Its fruit, which is oblong and resembles a small cucumber, transitions from green when immature to an orange-yellow color when fully mature. Bitter melon is widely recognized and consumed across Asia, primarily for its nutritional and medicinal benefits. Its medicinal uses, particularly for its hypoglycemic, anticancer, and hypocholesterolemic properties, are well-documented. The plant’s fruit pulp, seeds, and leaves are also known to be rich in phytochemicals, such as phenolics and carotenoids, which offer numerous health benefits1,2. These compounds, which vary during fruit maturation, are responsible for the plant’s antioxidant and nutraceutical properties. For instance, studies have shown that the maturation process in various fruits, including M. charantia, significantly impacts phytochemical content, as seen in other fruits like avocado, tomato, pear, and apple3,4. Additionally, the plant has a wide range of traditional medicinal applications, including treatment for Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, cancer, microbial infections, and even HIV/AIDS5. Nutritional analysis has further revealed that M. charantia boasts a high nutritional profile among cucurbit plants, containing carbohydrates, proteins, fibers, vitamins, and essential minerals. Its high-water content, approximately 93.2%, combined with significant protein and lipid levels, underscores its importance as a nutritionally valuable crop6,7.

While M. charantia is well-known for its medicinal and nutritional properties, there is a growing concern regarding the contamination of agricultural soils by heavy metals due to the increasing use of untreated industrial and municipal wastewater for irrigation. This issue is particularly pressing in developing countries, where the scarcity of freshwater forces local farmers to rely on polluted water sources for crop production. Industrial and sewage wastewater is often laden with toxic heavy metals such as cadmium, lead, and chromium, which accumulate in the soil and are absorbed by plant roots, eventually being translocated to edible plant parts8,9,10. This heavy metal contamination not only affects crop yield and quality but also poses significant health risks to consumers. Despite the extensive research on the medicinal benefits of M. charantia, few studies have explored the plant’s response to heavy metal stress, particularly in terms of its morphological, physiological, and biochemical traits. There remains a significant gap in understanding how nutrient and heavy metal toxicity from contaminated water influences the antioxidant activity and phytochemical content of this important crop. Previous studies have primarily focused on the therapeutic uses of M. charantia, with limited attention paid to the risks posed by environmental contamination.

Given the increasing use of polluted water for irrigation, it is hypothesized that M. charantia irrigated with municipal and industrial effluents will exhibit adverse effects on its growth, morphology, and physiological processes. Specifically, the study hypothesizes that exposure to heavy metals will lead to oxidative stress in the plant, prompting the activation of its antioxidant defense mechanisms. Key enzymes such as catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and peroxidase (POD) are expected to play a significant role in mitigating the effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by metal toxicity11,12. This study anticipates that metal accumulation in M. charantia will impact on the levels of key phytochemicals, potentially altering the plant’s overall nutraceutical value. The research aims to enhance understanding of the biochemical responses of M. charantia to environmental stress, addressing a significant gap in the current literature.

Several studies have demonstrated the harmful effects of heavy metals on plant health, particularly their role in inducing oxidative stress and disrupting cellular metabolism. Metals such as cadmium, lead, and chromium are known to interfere with normal plant functions by generating reactive oxygen species, which damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids13. Plants often respond to such stress by upregulating antioxidant enzymes to neutralize ROS, a defense mechanism observed in various species exposed to metal toxicity. In cucurbit plants, metal accumulation has been shown to negatively impact photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, and overall growth14. However, research specifically focusing on the response of M. charantia to heavy metal contamination is limited. Most available studies concentrate on the plant’s medicinal properties and phytochemical profile, with few addressing how environmental pollutants affect its biochemical and physiological traits. Additionally, the impact of heavy metals on the plant’s antioxidant system and its ability to produce health-promoting phytochemicals under stress conditions remain largely unexplored. Addressing this gap is crucial, as heavy metals, unlike organic pollutants, are non-degradable and persist in the environment, posing long-term risks to both plant and human health. This study, therefore, seeks to investigate the effects of heavy metal and nutrient toxicity on M. charantia, focusing on its growth, antioxidant activity, and phytochemical content.

The primary objective of this study is to examine the impact of nutrient and heavy metal toxicity, derived from municipal and industrial effluent water, on the morphology, physiology, and antioxidant activity of M. charantia. By analyzing the plant’s biochemical responses and phytochemical content under these conditions, the study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the potential risks associated with the use of contaminated water for crop irrigation.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

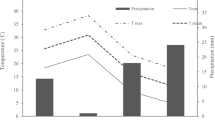

The experiment was performed using a completely randomized design (CRD), at the Women University of Sialkot, Pakistan. The wastewater utilized in this study was sourced from municipal effluents of the leather and marble industries in Sialkot, Pakistan, located at approximately 32.5° N latitude and 74.5° E longitude. 1-liter wastewater samples were collected in acid-washed polyethylene bottles and describing the storage conditions at 4 °C for no more than 48 h before analysis. The preparation method should include filtration through a 0.45 μm membrane to remove particulate matter and acid digestion using 5 mL of concentrated HNO₃ for 24 h at 100 °C. Additionally, the analytical method utilized, such as inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), should be clearly stated, along with calibration procedures using certified reference materials for heavy metals like cadmium, lead, and nickel.

Seeds of Momordica charantia (bitter gourd) were sourced from the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), Islamabad. Initially, pots containing healthy garden soil from Government College Women University Sialkot (GCWUS), characterized by a neutral pH, were selected. Bitter gourd seeds were sown at a depth of approximately half an inch, ensuring the maintenance of both genetic and physical purity. Germination of M. charantia seeds is generally slow and uneven, leading to variability in plant growth and fruit ripening. To address this, the seeds were pre-soaked in water for 24 h to promote uniform germination. After pre-germination, the seeds were sown, and the pots were irrigated with two types of water: one control group received freshwater, and the other treated with wastewater, including household, marble, and leather industry effluents.

Approximately 10–15 days post-germination, excess seedlings were thinned to reduce competition, ensuring optimal growth conditions for the remaining plants. After 20–25 days, staking was provided to each plant to support vine growth, and the trailing of vines was monitored daily until the fruiting stage. The greenhouse conditions were maintained with a temperature range of 19–21 °C (night to day) and a relative humidity of approximately 75%. The experimental design followed a completely randomized approach to evaluate the effects of contaminated wastewater on the morphology, physiology, antioxidant activity, and phytochemical content of M. charantia. Irrigation treatments were administered as outlined in Table 1. Upon maturation, leaf samples were collected from both freshwater- and wastewater-irrigated plants. These samples were then analyzed for heavy metal and salt content using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), providing quantitative data on the accumulation of contaminants in the plant tissues.

In Table 1, the terms “CR1,” “CR2,” and “CR3” represent the different replicates of the control treatment used in the experiment. Specifically, “CR1” stands for Control Replicate 1, “CR2” for Control Replicate 2, and “CR3” for Control Replicate 3. Each replicate ensures that the control group’s responses are accurately assessed. The treatment groups are also designated with “T” followed by a number i.e., “T1” refers to Treatment 1 (Household Water), “T2” indicates Treatment 2 (Marble Water), and “T3” signifies Treatment 3 (Leather Water).

Morphological analysis

After 10 to 15 weeks of growth, the plants were evaluated for key morphological traits and categorized into vegetative and reproductive characteristics. Vegetative traits measured included plant height, number of leaves, leaf color, leaf size, leaf texture, and root length. In terms of reproductive traits, the number and shape of flowers, flower color, number of inflorescences, and the number of sepals and petals were recorded to assess the reproductive development of M. charantia.

Chlorophyll content analysis

The chlorophyll content in the leaves of M. charantia was quantified using the method outlined by15. One gram of leaf tissue from each sample was homogenized into a paste, followed by the addition of 20 mL of 80% acetone and 0.5 g of magnesium carbonate powder. The mixture was then incubated at 4 °C for four hours. After incubation, the sample was centrifuged at 500 rpm for 5 min and subsequently filtered. A control sample, consisting of 20 mL of 80% acetone without any leaf tissue or additives, was prepared and treated in the same manner to establish a baseline absorbance. The optical density (OD) of the resulting supernatant from the samples was measured spectrophotometrically at wavelengths of 645 nm and 663 nm, using the control sample as a reference. The concentrations of chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, and total chlorophyll in both control and experimental samples were calculated using the following formula:

Phytochemical analysis

The extracts from the leaves stems, and roots of M. charantia were prepared for qualitative phytochemical screening to identify the presence of bioactive compounds. Initially, the plant materials were thoroughly cleaned to remove any soil, dust, or contaminants. Following cleaning, the materials were dried in a shaded area at room temperature to prevent degradation of sensitive phytochemicals. Once completely dried, the plant parts were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle or a mechanical grinder to increase the surface area for extraction. Approximately 50 g of each powdered sample were then subjected to extraction using 250 mL of methanol. This extraction was carried out through a maceration process, where the powdered plant material was allowed to steep in methanol for 48 h with occasional shaking to enhance the dissolution of phytochemicals. After the maceration period, the extracts were filtered through Whatman filter paper to remove any remaining particulate matter, yielding clear liquid filtrates.

The resulting filtrates were concentrated using a rotary evaporator at a controlled temperature of 40 °C to 50 °C, reducing the pressure to facilitate solvent removal without degrading heat-sensitive compounds. The concentrated extracts were then stored in sealed containers for further analysis. To test phenological compounds, 5 mL of distilled water was added to the solvent extracts from both control and experimental groups. The mixture was thoroughly shaken to ensure proper mixing, after which 5 drops of a 5% ferric chloride solution were added. The development of a dark greenish color indicated the presence of phenolic compounds, which are known for their antioxidant properties and health benefits16. Saponins were detected using the foam test. In this test, 50 mg of each extract was mixed with 20 mL of distilled water in a test tube and shaken vigorously for 15 min. The formation of a stable foam layer of approximately 2 cm in height confirmed the presence of saponins, which are recognized for their potential to enhance immune function and exhibit anti-inflammatory effects17. For tannin detection, 0.5 g of each extract was mixed with 1 mL of distilled water in a test tube. Following this, 2–3 drops of ferric chloride solution were added. The formation of a blue-black or blue-green precipitate confirmed the presence of tannins, compounds that have astringent properties and are associated with various health benefits17. Flavonoids were identified through the Shinoda test. To perform this test, a few drops of a 10% ammonium hydroxide solution were added to the extracts. The appearance of a yellow coloration indicated the presence of flavonoids, which are known for their role in plant defense and antioxidant activity18.

Antioxidant activity analysis

Methanolic extracts from all plant samples were prepared using the maceration method19, with slight modifications. Powdered plant material was mixed with methanol and agitated at 200 rpm for 24 h at 28 °C. After filtration, the residual material was soaked in fresh solvent, briefly agitated, and filtered again. This extraction process was repeated three times to ensure complete extraction of phytochemicals. Extract concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg/mL were prepared, along with standard antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) in methanol. The free radical scavenging activity of the extracts was assessed20. One mL of a 0.3 mM DPPH solution in methanol was added to 2.5 mL of each plant extract sample and allowed to react at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was measured spectrophotometrically at 518 nm in triplicate. Methanol containing DPPH served as the control. Antioxidant activity was calculated and expressed as mean values with standard deviations.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The experimental data was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the significance of differences between control and treated groups. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the relationships between metal accumulation, physiological traits, and phytochemical content, while regression analysis was applied to assess the impact of various treatments on plant growth, antioxidant activity, and phytochemical composition. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 21).

Results

Water sample analysis

Water plays a vital role in supporting life and is utilized in various aspects of daily living. However, water quality varies depending on its source, influencing not only human health but also the survival and growth of other organisms. For instance, saline water possesses distinct properties compared to freshwater. The present study aimed to investigate the effects of different water treatments on the morphology, physiology, antioxidant activity, and phytochemical composition of M. charantia. Water samples from diverse sources, including household wastewater, marble industry effluents, and leather industry discharge, were used alongside control water for comparative analysis. The study’s findings revealed that the pH of household, marble, and control water samples was alkaline, with a mean value of 8.4, whereas leather industry wastewater exhibited acidic characteristics with a pH of 4.64 (Table 2). Electrical conductivity was significantly higher in wastewater samples compared to the control, indicating elevated salinity levels. Chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD) were also notably higher in wastewater samples, suggesting the presence of decaying organic matter. In contrast, COD and BOD were absent in control water, confirming the absence of organic pollutants. Furthermore, all wastewater samples were enriched with salts and heavy metals. Notably, the highest concentrations of arsenic (0.12 mg/L) and cadmium (0.84 mg/L) were detected in leather industry wastewater, while lead was most concentrated in the control water (0.78 mg/L), and the highest zinc levels (0.67 mg/L) were found in marble factory wastewater. These findings underscore the potential risks posed by contaminated water sources to both plant health and environmental safety.

Effect of treatments on seed germination

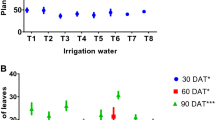

Each pot containing M. charantia plants was subjected to different water treatments: Control, Household, Marble, and Leather (Figs. 1 and 2). The germination process was monitored and analyzed for each treatment. The results revealed that pots irrigated with control water exhibited the earliest germination, achieving approximately a 90% germination rate. Pots treated with household water also demonstrated a high germination rate of around 90%, albeit with a delayed onset compared to the control. In contrast, pots receiving marble water treatment began germinating later and achieved a 75% germination rate. Pots irrigated with leather water exhibited the latest germination, with an 80% germination rate. These findings indicate that the quality of irrigation water significantly affects crop production. Factors such as water alkalinity, pH, salt content, and heavy metal concentrations can impact germination and overall plant health. Specifically, the presence of control and household water resulted in earlier germination, whereas marble and leather water treatments led to delayed germination, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This underscores the critical role of water quality in optimizing seedling development and crop productivity.

Effect of waste treatments on plant morphology

After harvesting M. charantia plants from each pot, various morphological parameters were measured, including plant height, stem length, root length, and the number of branches and leaves, using appropriate equipment. The results indicated that the control group exhibited the highest growth across most parameters, except for the number of leaves and branches, which were greatest in the household treatment group. Fruits were exclusively observed in the marble treatment group. Among the wastewater treatments, the household group demonstrated the highest growth, followed by the marble group with moderate growth, and the leather group with the lowest growth. Statistical analysis of the morphological data using one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference with a p-value of 0.05. This analysis confirmed a highly significant disparity between the control and experimental groups, as detailed in Table 3. The study highlights that water quality significantly impacts morphological development and fruiting success, with varying effects observed across different water treatments.

Chlorophyll content determination

The results showed that chlorophyll-a levels were highest in the control group at 38.1 mg/mL, followed by the marble group at 27.9 mg/mL, the leather group at 26.7 mg/mL, and the household group at 22.9 mg/mL (Table 4). For chlorophyll-b, the control group had the highest concentration at 12.3 mg/mL, while the marble group had 10.2 mg/mL, the leather group had 7.7 mg/mL, and the household group had 7.7 mg/mL. Total chlorophyll content was also highest in the control group at 42.2 mg/mL, with the marble and leather groups having 38.7 mg/mL and 34.1 mg/mL, respectively. The physiological analysis indicated that the control group had significantly higher levels of chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, and total chlorophyll compared to the experimental groups.

The marble and household groups had higher chlorophyll concentrations than the leather group, but these were still lower than those observed in the control group. Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA revealed a p-value of 0.05, indicating a highly significant difference in chlorophyll levels between the control and wastewater-treated groups, as shown in Table 4. This finding underscores the impact of water quality on chlorophyll content and overall plant health.

Phytochemical analysis

The impact of different water sources on the phytochemical content in the buds, leaves, and fruits of M. charantia was evaluated over one growing season. This study also measured shoot and root length, leaf morphology, yield efficiency, and fruit weight. The plants were irrigated with four types of water: control water, household water, marble water, and leather water. Phytochemical analyses were performed using high-performance optical emission spectrometry. The results revealed that the plants irrigated with various water sources exhibited elevated levels of total flavonoids, phenolic compounds, tannins, and saponins. Methanolic extracts of powdered aerial parts and roots were prepared to analyze these phytochemicals, as detailed in Table 5. M. charantia is known for its diverse phytochemical profile, which contributes to its use as an antifungal, anti-diabetic, and antioxidant agent. Flavonoids are recognized for their potent antioxidant properties, while alkaloids are noted for their anticancer and anti-malarial effects.

Antioxidant activity

Methanolic extracts of various parts of the bitter gourd plant—leaves, roots, and stems—were prepared using the maceration method to assess antioxidant activity through the DPPH assay (Fig. 4). DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) is a stable nitrogen-containing free radical that absorbs at 517 nm and is commonly used to evaluate antioxidant activity in natural substances21. This assay involves observing the color change of DPPH solutions from violet to colorless or yellowish, indicating the reduction of the DPPH radical22. Antioxidants in plant extracts can neutralize DPPH radicals, thereby reducing the violet color. In this study, methanolic extracts from the control group—comprising leaves, roots, and stems—demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity compared to the experimental groups. Additionally, ascorbic acid (used as a standard) exhibited superior antioxidant activity relative to BHA (butylated hydroxyanisole), the control group, and the experimental groups, as shown in Table 6.

Discussion

This study investigates the impact of wastewater sources—leather, household, and marble effluents—on the growth, physiology, and antioxidant activities of Momordica charantia (bitter melon). The water analysis demonstrated that leather wastewater exhibited the highest levels of heavy metals, including cadmium (0.84 mg/L) and arsenic (0.12 mg/L), along with significantly elevated electrical conductivity (4780 µS/cm), total dissolved solids, and total suspended solids compared to control water, which showed no heavy metal contamination. The reason behind the higher accumulation of heavy metals in leather water can be attributed to the tanning processes used in the leather industry, which involve the use of heavy metals like chromium and cadmium. However, the absence of chromium in the marble and leather wastewater can be explained by the specific chemical processes employed in these industries, which do not involve chromium, or where chromium might be trapped or precipitated in waste sludge before reaching effluents. This agrees with studies23,24,25,26,27,28,29, which reported similar heavy metal profiles in wastewater from industrial effluents.

The study found that heavy metal contamination, particularly cadmium and arsenic, significantly inhibited seed germination, with germination rates falling to 75–80% in the leather and marble treatments, compared to 90% in control plants. The mechanism for this reduction can be logically explained by the toxic effects of heavy metals on seed metabolic activities. Heavy metals such as cadmium interfere with water and nutrient uptake, disrupt enzymatic activities critical to seed germination, and induce oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage before visible symptoms emerge. This is consistent with the findings of30,31,32,33,34, who noted that cadmium uptake by plants can reach toxic levels before stress symptoms appear. Additionally, the increased salinity and conductivity of wastewater further disrupt the osmotic balance in seeds, leading to physiological stress and reduced germination35,36,37.

From a physiological perspective, the reduction in plant growth parameters, such as shoot length, root length, and biomass, observed in wastewater-treated plants can be logically attributed to the combined effects of heavy metal toxicity and water salinity. Heavy metals inhibit cell division and elongation in root and shoot meristems, which stunts overall plant growth. Moreover, the high salinity in wastewater increases osmotic stress, making it harder for plants to uptake water and nutrients, ultimately leading to reduced turgor pressure and slower growth. This is aligned with the previous findings where similar reductions in morphological traits were observed under water stress and heavy metal contamination38,39.

The decrease in chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b levels in wastewater-treated plants further supports the hypothesis that heavy metal and salinity stress impair photosynthesis. Heavy metals disrupt the biosynthesis of chlorophyll by interfering with magnesium incorporation into the chlorophyll molecule and by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage chloroplasts. This agrees with studies40,41,42, which noted that wastewater with high metal content inhibits chlorophyll synthesis, particularly chlorophyll-a. Additionally, water stress due to high salinity leads to stomatal closure, reducing CO2 uptake, and consequently, the rate of photosynthesis43,44,45,46. Reduced photosynthesis directly impacts plant growth and biomass accumulation47, as seen in this study.

Interestingly, the increased antioxidant activity observed in wastewater-treated plants, particularly those irrigated with marble water, can be reasoned as a defensive response to oxidative stress induced by heavy metal toxicity. Antioxidants, such as phenolic compounds, are synthesized by plants in response to oxidative damage caused by ROS generated under stress conditions. The higher phenolic content (67.4 mg/g) and DPPH radical scavenging activity (85.3%) in marble-treated plants suggest that plants activate their antioxidant defense systems to mitigate ROS damage, a finding consistent with previous studies48. This antioxidant response is vital for plant survival under stress, as it helps neutralize ROS and prevent cellular damage.

The study also highlights the importance of electrical conductivity (EC) in determining the suitability of water for irrigation. Water with EC levels above 3 dS/m, such as marble wastewater (4.78 dS/m), is considered unsuitable for irrigation due to its ability to increase soil salinity and disrupt plant water relations. As plants absorb water with high salinity, they expend more energy in osmoregulation, leading to reduced growth, as seen in the present study. This finding aligns with the work of49, who noted that elevated EC in irrigation water can have detrimental effects on plant health.

The reduction in morphological and physiological parameters in wastewater-treated plants is logically linked to the combined effects of heavy metal toxicity and increased salinity. These stressors impair water uptake, nutrient transport, enzymatic activities, and photosynthesis, resulting in poor growth and reduced chlorophyll content50. Additionally, the observed increase in antioxidant activity indicates the plants’ attempt to counteract oxidative stress induced by heavy metal exposure. Therefore, while industrial wastewater may provide nutrients, its high content of toxic heavy metals and salts poses significant risks to plant health and long-term agricultural sustainability. These findings emphasize the need for effective wastewater treatment before agricultural reuse to mitigate the risks associated with heavy metal and salinity contamination.

Conclusions

This study highlights the significant effects of various types of wastewaters, including household, marble, and leather industry effluents, on the growth and development of Momordica charantia. The results demonstrate that water quality, characterized by pH, electrical conductivity, and the presence of heavy metals, plays a crucial role in seed germination, plant morphology, and physiological parameters. The highest germination rates were observed in control and household water treatments, while the marble and leather wastewater treatments caused delayed germination and inhibited plant growth. Furthermore, the analysis of plant morphology revealed that the household wastewater treatment led to the highest growth in most parameters, followed by the marble wastewater group, while the leather wastewater treatment showed the lowest growth performance. Fruit development was observed only in the marble wastewater treatment, suggesting that the type and concentration of contaminants in water influence both vegetative and reproductive traits of plants. These findings emphasize the importance of water quality in agricultural practices, particularly in areas where industrial wastewater is used for irrigation, and provide valuable insights into the potential risks and effects of contaminated water on crop health and productivity. Further studies are necessary to explore the long-term effects of industrial effluents on plant health and to develop strategies for mitigating these adverse impacts.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Girón, L. M., Freire, V., Alonzo, A. & Cáceres, A. Ethnobotanical survey of the medicinal flora used by the caribs of Guatemala. J. Ethnopharmacol. 34(2–3), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8741(91)90035-C (1991).

Lans, C. & Brown, G. Ethnoveterinary medicines used for ruminants in Trinidad and Tobago. Prev. Vet. Med. 35(3), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-5877(98)00066-x (1998).

Grover, F. W. Inductance Calculations: Working Formulas and Tables. (Courier Corporation, 2004).

Nagarani, G., Abirami, A. & Siddhuraju, P. Food prospects and nutraceutical attributes of Momordica species: a potential tropical bioresource—A review. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 3(3–4), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fshw.2014.07.001 (2014).

Speirs, J. & Brady, C. J. Modification of gene expression in ripening fruit. Funct. Plant. Biol. 18(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1071/PP9910519 (1991).

Kubola, J. & Siriamornpun, S. Phytochemicals and antioxidant activity of different fruit fractions (peel, pulp, aril and seed) of Thai gac (Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng). Food Chem. 127(3), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.115 (2011).

Grover, J. K. & Yadav, S. P. Pharmacological actions and potential uses of Momordica charantia: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 93(1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.035 (2004).

Saad, D. Y., Soliman, M. M., Baiomy, A. A., Yassin, M. H. & El-Sawy, H. B. Effects of Karela (Bitter Melon; Momordica charantia) on genes of lipids and carbohydrates metabolism in experimental hypercholesterolemia: Biochemical, molecular and histopathological study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-1833-x (2017).

Fongmoon, D. Antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) Extract cultured in Lampang, Thailand. Int. J. Sci. 10(2), 18–25 (2013).

Lu, Y. L. et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of different wild bitter gourd cultivars (Momordica charantia L. var. abbreviata seringe). Study 52, 427–434 (2011).

Navabpour, S., Yamchi, A., Bagherikia, S. & Kafi, H. Lead-induced oxidative stress and role of antioxidant defense in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 26(4), 793–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-020-00777-3 (2020).

Sofo, A., Scopa, A., Nuzzaci, M. & Vitti, A. Ascorbate Peroxidase and catalase activities and their genetic regulation in plants subjected to Drought and Salinity stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16(6), 13561–13578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160613561 (2015).

Ng, T. B., Chan, W. Y. & Yeung, H. W. Proteins with abortifacient, ribosome-inactivating, immunomodulatory, antitumor and anti-AIDS activities from Cucurbitaceae plants. Gen. Pharmacol. 23(4), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-3623(92)90131-3 (1992).

Raman, A. & Lau, C. Anti-diabetic properties and phytochemistry of Momordica charantia L. (Cucurbitaceae). Phytomedicine 2(4), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80080-8 (1996).

Kamble, P. G., Sanjay, M. R., Ranjeet, T. & Anupreet, G. Estimation of chlorophyll content in young and adult leaves of Zea mays. Univ. J. Environ. Res. Technol. 306–310 (2015).

Trease, G. E. & Evans, W. C. Pharmacognosy, 11th edn. 45–50 (Bailliere Tindall, 1989).

Hossain, M. A. & Nagooru, M. R. Biochemical profiling and total flavonoid contents of leaves crude extract of endemic medicinal plant Cordyline terminalis L. Kunth. Pharmacogn J. 3(24), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2011.24.5 (2011).

Shah, M. D. & Hossain, M. A. Total flavonoids content and biochemical screening of the leaves of tropical endemic medicinal plant Merremia borneensis. Arab. J. Chem. 7(6), 1034–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.12.033 (2014).

Walia, R., Hedaitullah, M., Naaz, S. F., Iqbal, K. & Lamba, H. S. Benzimidazole derivatives—An overview. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Chem. 1(3), 565–574. https://doi.org/10.30574/gscbps.2022.20.3.0370 (2011).

Choi, J. S., Kim, H. Y., Seo, W. T., Lee, J. H. & Cho, K. M. Roasting enhances antioxidant effect of bitter melon (Momordica charantia L.) increasing flavan-3-ol and phenolic acid contents. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 21, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-012-0003-7 (2012).

Ramadan, S. I., Shalaby, M. A., Afifi, N. & El-Banna, H. A. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of Silybum marianum plant in rats. Int. J. Agro Vet. Med. Sci. 5, 541–547 (2011).

Molyneux, P. The use of the stable free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for estimating antioxidant activity. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 26(2), 211–219 (2004).

Irfan, M., Ahmad, A. & Hayat, S. Effect of cadmium on the growth and antioxidant enzymes in two varieties of Brassica juncea. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 21(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2013.08.001 (2014).

Li, X., Kellaway, R. C., Ison, R. L. & Annison, G. Digesta flow studies in sheep fed two mature annual legumes. J. Agric. Res. 45(4), 889–900. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9940889 (1994).

Fakayode, S. & Onianwa, P. Heavy metal contamination of soil and bioaccumulation in Guinea grass (Panicum maximum) around Ikeja Industrial Estate, Lagos, Nigeria. Environ. Geol. 43, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00254-002-0633-9 (2002).

Imperato, M. et al. Spatial distribution of heavy metals in urban soils of Naples city (Italy). Environ. Pollut. 124(2), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0269-7491(02)00478-5 (2003).

Divyapriya, S., Sowmia, C. & Sasikala, S. Synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and antimicrobial activity of Murraya koenigii. World J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 3(12), 1635–1645 (2014).

Walter, H. The water economy and the hydrature of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Physiol. 6(1), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.06.060155.001323 (1955).

Bernstein, L. Osmotic adjustment of plants to saline media. I. Steady state. Am. J. Bot. 48(10), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1961.tb11730.x (1961).

Indra, V. & Sivaji, S. Metals and organic components of sewage and sludges. J. Environ. Biol. 27(4), 723–725 (2006).

Agarwal, P. K., Singh, V. P. & Kumar, D. Biochemical changes in seedlings of Brassica nigra and Brassica campestris in response to mancozeb treatments. Plant Soil. ;50:121–125.Shukla, N., & Pandey, G. S. Effect of wastewater from an oxalic acid manufacturing plant on seed germination and seedling height in selected cereals. J. Environ. Biol. 12, 149–151 (1991). (1979).

Shukla, N., & Pandey, G. S. Effect of wastewater from an oxalic acid manufacturing plant on seed germination and seedling height in selected cereals. J. Environ. Biol. 12, 149–151 (1991). (1979).

Neelam, S. & Sahai, R. Effect of fertilizer factory effluent on seed germination, seedling growth, pigment content, and biomass of Sesamum indicum. J. Environ. Biol. 9, 45–50 (1988).

Mosse, K. P. M., Patti, E. W., Christen, T. R. & Cavagnaro, T. R. Winery wastewater inhibits seed germination and vegetative growth of common crop species. J. Hazard. Mater. 180(1–3), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.02.069 (2010).

Kanwal, A., Farhan, F., Sharif, M. U., Hayyat, L. & Shahzad, G. Z. Gafoor. Effect of industrial wastewater on wheat germination, growth, yield, nutrients, and bioaccumulation of lead. Sci. Rep. 10, 11361 (2020).

Gaafar, A. A. et al. Ascorbic acid induces the increase of secondary metabolites, antioxidant activity, growth, and productivity of the common bean under water stress conditions. Plants 9(5), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9050627 (2020).

Khan, M. G., Konjit, G., Thomas, A., Eyasu, S. S. & Awoke Impact of textile wastewater on seed germination and some physiological parameters in pea (Pisum sativum L.), lentil (Lens Esculentum L.), and gram (Cicer arietinum L). Asian J. Plant. Sci. 10, 269–273. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajps.2011.269.273 (2011).

Fatemi, R., Yarnia, M., Mohammadi, S., Vand, E. K. & Mirashkari, B. Screening barley genotypes in terms of some quantitative and qualitative characteristics under normal and water deficit stress conditions. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2022071. (2023).

D’Addazio, V. et al. Impact of metal accumulation on photosynthetic pigments, carbon assimilation, and oxidative metabolism in mangroves affected by the Fundāo Dam tailings plume. Coasts 3, 125–144. https://doi.org/10.3390/coasts3020008 (2023).

Zandi, P. & Schnug, E. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidant responses, and implications from a microbial modulation perspective. Biology 11(2), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology11020155 (2022).

Vasilachi, I. C., Stoleru, V. & Gavrilescu, M. Analysis of heavy metal impacts on cereal crop growth and development in contaminated soils. Agriculture 13, 1983. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101983 (2023).

Hnilickova, H., Kraus, K., Vachova, P. & Hnilicka, F. Salinity stress affects photosynthesis, malondialdehyde formation, and proline content in Portulaca oleracea L. Plants 10(5), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10050845 (2021).

Hu, H. J. et al. A model for the relationship between plant biomass and photosynthetic rate based on nutrient effects. Ecosphere 12(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3678 (2021).

Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under abiotic stress: revisiting the crucial role of a universal defense regulator. Antioxidants 9(8), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9080681 (2020).

Muhammad, M. Soil salinity and drought tolerance: An evaluation of plant growth, productivity, microbial diversity, and amelioration strategies. Plant. Stress. 11, 100319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stress.2023.100319 (2024).

Verma, A., Gupta, A., Gaharwar, U. S. & Rajamani, P. Effect of wastewater on physiological, morphological, and biochemical levels and its cytotoxic potential on Pisum sativum. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 2017–2034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-023-04941-6 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. OsTTG1, a WD40 repeat gene, regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in rice. Plant. J. 107(1), 198–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.15285 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Effective extraction of cr(VI) from hazardous gypsum sludge via controlling the phase transformation and chromium species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52(22), 13336–13342. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b02213 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. Different pathways for cr(III) oxidation: Implications for cr(VI) reoccurrence in reduced chromite ore processing residue. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54(19), 11971–11979. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c01855 (2020).

Liu, W. et al. Recycling mg(OH)2 nanoadsorbent during treating the low concentration of cr(VI). Environ. Sci. Technol. 45(5), 1955–1961. https://doi.org/10.1021/es1035199 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project No. (RSP2025R390), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

This research was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project No. (RSP2025R390), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NB: Experimentation and data Curation; MM, RQ: Methodology, supervision, Writing and drafting, and research design; TA, HQ: Validation and Software, writing, Investigation, draft-ing, statistical analysis, and validation; IS, SI: writing, Software, Resource, research design, validation, data collection, drafting, statistical analysis; NU, WS, WZ: writing, funding, statis-tical analysis, Resource, software, validation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and declare that they have no competitive interest.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We all declare that manuscript reporting studies do not involve any human participants, human data, or human tissue. So, it is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Batool, N., Munazir, M., Qureshi, R. et al. Morphological and physiological responses of Momordica charantia to heavy metals and nutrient toxicity in contaminated water. Sci Rep 14, 30200 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80234-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80234-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of selenium and compost on physiological, biochemical, and productivity of chili under chromium stress

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

From waste to resource: evaluating contaminated water as a dual-edged tool for crop growth and phytochemical enhancement

Environmental Earth Sciences (2025)