Abstract

The effect of W and WO3 electrodes on the ferroelectric characteristics of HZO (Zr-doped HfO2)-based MFM (metal-ferroelectric-metal) capacitors was investigated. During the deposition of tungsten, the W electrode was formed using only Ar gas, while the WO3 electrode was formed using a mixture of Ar and O2 gases. The W-based MFM capacitors exhibited superior remnant polarization (2Pr of 107.9 µC/cm2 at 700 oC) compared to the WO3-based capacitors; however, their endurance performance was degraded. In contrast, the WO3-based capacitors showed endurance performance enhanced by three orders of magnitude due to the oxygen-rich reservoir effect. The oxygen introduced during the deposition of WO3 prevented the oxygen scavenging effect of tungsten. Consequently, excessive generation of oxygen vacancies in the HZO layer was suppressed, resulting in improved endurance performance. These results were quantitatively confirmed through TEM, XPS, and XRD analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hafnia-based ferroelectric random-access memory (FeRAM) has attracted tremendous interest as one of the future candidates for nonvolatile memory applications because of its thickness scalability and CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) process compatibility1,2,3,4,5,6,7. However, its endurance characteristic, which is one of the crucial reliability properties of FeRAM, is not comparable to that of commercialized memory devices like DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory). The endurance characteristics are significantly affected by interface traps, such as oxygen vacancies, in hafnia-based ferroelectric materials8. Therefore, optimizing the amount of oxygen vacancies in the ferroelectric layer is key to improving the endurance performance of ferroelectric-based devices. One of the crucial factors that governs the amount of oxygen vacancies in ferroelectric materials is the choice of material for the metal electrode. Tungsten has been widely used for ferroelectric devices because of its CMOS compatibility. Moreover, compared to TiN-based ferroelectric capacitors, ferroelectric capacitors with tungsten metal electrodes have shown better ferroelectricity due to their stronger tensile stress9. However, tungsten-based ferroelectric capacitors also exhibit poor endurance performance due to the strong oxygen scavenging effect of tungsten, which induces an excessive amount of oxygen vacancies in the ferroelectric layer10.

In this work, the device performance of HZO-based metal-ferroelectric-metal (MFM) capacitors with two different metal electrodes (i.e., metallic tungsten for W-based capacitors and oxidized tungsten for WO3-based capacitors) was compared and investigated for future FeRAM applications. O2 gas was added during the deposition of the tungsten metal electrode to form an oxygen reservoir and to prevent the oxygen scavenging effect of the tungsten metal electrode. The ferroelectric characteristics, including the endurance performance of W- and WO3-based MFM capacitors, were investigated. Quantitative analyses such as TEM, EDS, XPS, and GIXRD were conducted to analyze changes in the atomic bonding within the HZO layer and phase transitions in the W and WO3 metal electrode layers.

Materials and methods

MFM (metal-ferroelectric-metal) capacitors were fabricated, as shown in Fig. 1 First, standard cleaning processes (i.e., SPM, SC-1, and SC-2) and diluted HF (1:50) cleaning were performed on (100) p-type Si wafers with a resistivity of < 0.005 Ω∙cm. Then, the tungsten bottom electrode was deposited by DC sputtering. Note that two different gas flow conditions were used for the W deposition: (i) only Ar and (ii) Ar and O2. The power and process time were identical for all samples. Afterwards, a 10-nm-thick HZO (Zr-doped HfO2) layer was deposited by thermal ALD at a deposition temperature of 250 oC. Tetrakis (ethylmethylamino) hafnium (TEMAHf), tetrakis (ethylmethylamino) zirconium (TEMAZ), and H2O were used as source precursors for the ALD process to deposit the HZO film. Subsequently, tungsten was deposited by DC sputtering for the top electrode, followed by photolithography, etching, PR ashing, and PR stripping to define the contact pattern. The device area size is 80 × 80 µm2. The fabricated MFM capacitors were annealed at 400/500/600/700 oC for 30 s in an N2 atmosphere using rapid thermal annealing (RTA) for post-metallization annealing (PMA) to crystallize the HZO film.

The device measurements were done with Keithley 4200 A-SCS parameter analyzer, to characterize the ferroelectric properties of those MFM capacitors. The current density versus voltage (I–V) and endurance characteristics were measured. A triangular waveform with the amplitude of 3 Vand 4 V was used to characterize the polarization-voltage (P-V) characteristics. A trapezoidal waveform with the amplitude of 3 V and 4 V was used for the endurance cycling. Note that the rise/fall time for both waveforms and the pulse width for trapezoidal waveform were set to 1 µs.

Results and discussions

Figure 2a and 2b show the Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images and High Angle Annular Dark Field (HAADF) images from the Electron Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) of W- and WO3-based capacitors at PMA temperature of 600 oC. As expected, W appeared in the top and bottom of the capacitor, while Hf and Zr were present in the intermediate layer. The EDS and XPS depth profiles in Fig. 2c and 2d confirmed that the oxygen content in the WO₃-based electrodes was significantly higher than that in W-based electrodes. The oxygen-rich nature of the WO₃ electrodes suggests a suppression of oxygen vacancies in the HZO layer, which is critical for improving endurance performance. The EDS analysis showed clear evidence of higher oxygen concentration in the top and bottom electrode layers of WO₃-based capacitors. This corroborates the hypothesis that WO₃ acts as an oxygen reservoir, preventing the oxygen scavenging effect of tungsten and thus reducing oxygen vacancy formation in the HZO layer. This is further supported by the XPS analysis in Fig. 3a and 3c, which showed a significant reduction in the oxygen vacancy-related suboxide peaks in WO₃-based capacitors.

XPS spectra of Hf 4f and W 4f were analyzed to further investigate the presence of oxygen vacancies. Figure 3a and c show the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of Hf 4f spectra from the HZO layer in W- and WO3-based capacitors at PMA temperature of 600 oC. For W-based capacitors in Fig. 3a, the Hf 4f peaks appeared at higher binding energies (18.57 and 20.17 eV), indicating a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies in the HZO layer. The suboxide peak (HfO2-x) was prominent, making up approximately 46% of the total Hf 4f area, which signifies the existence of oxygen-deficient regions in the ferroelectric layer. The HfO2-x peak in the figure represents the suboxide peak, which is oxygen-deficient HfO2-xcaused by the redox reaction, indicating the presence of oxygen vacancies in the HZO layer11.

In contrast, the WO₃-based capacitors (Fig. 3c) exhibited lower binding energy peaks for Hf 4f (18.45 and 20.05 eV), with the suboxide peak contributing only 31% to the overall area. This reduction in oxygen vacancies can be attributed to the oxygen introduced during the deposition of WO₃, which helps fill the vacancies in the HZO layer. The XPS spectra of W 4f in Fig. 3b and d further confirmed this effect. While the W-based capacitors displayed strong peaks corresponding to metallic W (W 4f5/2 and W 4f7/2), the WO₃-based capacitors showed oxidized W states (WO₃-x), reflecting the oxygen-rich environment in these capacitors.

The added oxygen atoms can diffuse into the HZO layer and fill up the oxygen vacancies, as shown in Fig. 4. Tungsten metal exhibits a strong oxygen scavenging effect, inducing excessive oxygen vacancies and deteriorating the endurance performance, as observed in the W-based capacitor12. The addition of O2 gas oxidizes the metallic tungsten to WO3, creating an oxygen reservoir and suppressing the oxygen scavenging effect of W, as evidenced by the XPS analysis.

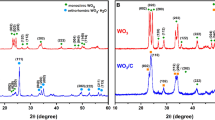

Figure 3e and 3f present the grazing-incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) patterns in the range of 20 ~ 70° (2θ) for W- and WO3-based capacitors. In the W-based capacitors, peaks corresponding to metallic W were observed around 40° and 60°. However, the WO₃-based capacitors exhibited additional peaks associated with tungsten oxides (WO₃), confirming the successful oxidation of the tungsten electrode. These results corroborate the XPS analysis of W 4f in Fig. 3b and 3d.

For various PMA temperatures, the measured pristine (before endurance cycling test) current density–vs.–voltage (I–V) and polarization–vs.–voltage (P–V) characteristics of W- and WO3-based MFM capacitors are shown in Fig. 5. The P-V measurements were performed using a triangular pulse with an amplitude of 3–4 V. The endurance characteristics of each sample were measured, as shown in Fig. 6. A trapezoidal waveform with an amplitude of 3–4 V, a pulse width of 1 µs, and rising/falling times of 1 µs was used for the endurance cycling. The triangular pulse was used for the P-V measurements. Note that the endurance cycling pulse and P-V measurement pulse were set to the same value (i.e., 3 V/3V and 4 V/4V).

Measured pristine 2Pr vs. the number of cycles of W-based MFM and WO3-based MFM capacitors at (a, b) 3 V, (c, d) 4 V. The number of endurance cycle is 100~ 108. The 10−1 indicates the pristine state. The annealing temperature was set to four different annealing temperatures (i.e., 400, 500, 600, and 700 ℃).

Table 1 summarizes the pristine 2Pr values and breakdown points in the endurance cycling of W- and WO3-based capacitors at various PMA temperatures and pulse amplitudes. The W-based capacitors exhibited excellent 2Pr characteristics, with a maximum value of 107.9 μm/cm2 at 700 ℃. The overall pristine 2Pr values of the WO3-based capacitors were lower compared to the W-based capacitors. This reduction can be attributed to the excessive oxygen in WO3, which causes the transformation of the o-phase to non-polar phases in the ferroelectric layer12. Although the pristine 2Pr of the WO3-based capacitors was lower than that of the W-based capacitors, the endurance performance was significantly enhanced by up to 3 orders of magnitude. This improvement is due to the reduced oxygen vacancies resulting from the oxygen-rich WO3electrode, as previously explained. Oxygen vacancies form undesirable conductive leakage paths in the HZO layer13,14. Consequently, the leakage paths were reduced with the decreased oxygen vacancies in the WO3-based capacitors, leading to enhanced endurance performance.

As shown in Fig. 7a, the performance of the capacitors fabricated in this work was benchmarked against previous studies (which were annealed at various annealing temperatures). The MFM capacitors annealed at 400 to 700 ℃ showed superior 2Pr compared to the previous works. The unusually high 2Pr of 107.9 µC/cm² in the W/HZO/W capacitors is noteworthy. We attribute this high remnant polarization to the combined effects of tensile stress and enhanced crystallization at high annealing temperatures (up to 700 °C). The W electrodes induce significant tensile strain on the HZO layer, which promotes the stabilization of the orthorhombic ferroelectric phase, leading to higher polarization. In Fig. 7b, the number of maximum endurances cycling before the breakdown of each ferroelectric-based capacitor are summarized and compared to each other. It turned out that the MFM capacitors in this work (vs. previous works8,10,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22) shows comparable endurance performance even with the superior 2Pr value showed in Fig. 7a. Although the pristine 2Pr of WO₃-based capacitors was lower than that of W-based capacitors, the superior endurance performance makes WO₃ a more viable candidate for FeRAM applications, where long-term reliability is critical. The trade-off between polarization and endurance performance highlights the importance of selecting electrode materials that can balance both properties effectively.

Conclusion

The impact of W and WO3 electrodes on HZO-based MFM capacitors was investigated and compared. The W-based MFM capacitors exhibited superior remnant polarization compared to the WO3-based capacitors. However, the W-based capacitors showed deteriorated endurance performance. In contrast, the WO3-based capacitors demonstrated enhanced endurance performance due to the oxygen-rich reservoir effect. The added oxygen in WO3 prevented the oxygen scavenging effect of tungsten, thereby suppressing the excessive generation of oxygen vacancies in the HZO layer, and consequently improving endurance performance. This result indicates that adjusting the Ar/O2 gas ratio during the deposition of the tungsten metal can significantly affect the endurance performance of ferroelectric devices for future FeRAM applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Walke, A. M. et al. La Doped HZO based 3D-Trench Metal-Ferroelectric-Metal Capacitors with high endurance (> 10¹²) for FeRAM Applications. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 45 https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2024.3368225 (2024).

Grenouillet, L. et al. IEEE,. in 2020 IEEE Silicon Nanoelectronics Workshop (SNW) 5–6. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/SNW49134.2020.9109941

Okuno, J. et al. in. IEEE International Memory Workshop (IMW) 1–3. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/IMW51251.2021.9439392 (IEEE, 2021).

Choi, Y., Park, H., Han, C. & Shin, C. Impact of CF₄/O₂ plasma passivation on endurance performance of Zr-Doped HfO₂ ferroelectric Film. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 44, 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2023.3267221 (2023).

Lee, S. et al. Analysis of wake-up reversal behavior induced by imprint in La: HZO MFM capacitors. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 2568–2574. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2023.3266815 (2023).

Choi, Y. et al. Experimental study of endurance characteristics of Al-doped HfO₂ ferroelectric capacitor. Nanotechnology 34, 185203. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/acb1f3 (2023).

Min, J. et al. Program/erase scheme for suppressing interface trap generation in HfO₂-based ferroelectric field effect transistor. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 42, 1280–1283. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2021.3081966 (2021).

Mallick, A., Lenox, M. K., Beechem, T. E., Ihlefeld, J. F. & Shukla, N. Oxygen vacancy contributions to the electrical stress response and endurance of ferroelectric hafnium zirconium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0133995 (2023).

Suh, Y. J. et al. Large polarization of Hf₀.₅ Zr₀.₅Ox Ferroelectric Film on InGaAs with Electric-Field Cycling and Annealing Temperature Engineering. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2024.3369400 (2024).

Segantini, G. et al. Interplay between strain and defects at the interfaces of Ultra-thin Hf0.5Zr0.5O2-Based Ferroelectric Capacitors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 9, 2300171. https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202300171 (2023).

Lee, Y., Goh, Y., Hwang, J., Das, D. & Jeon, S. The influence of top and bottom metal electrodes on ferroelectricity of hafnia. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 68, 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2021.3049970 (2021).

Wang, X., Slesazeck, S., Mikolajick, T. & Grube, M. Modulation of Oxygen Content and Ferroelectricity in Sputtered Hafnia-Zirconia by Engineering of Tungsten Oxide bottom electrodes. Adv. Electron. Mater. 10, 2300798. https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202300798 (2024).

Choi, Y. et al. Impact of chamber/annealing temperature on the endurance characteristic of Zr: HfO2 ferroelectric capacitor. Sensors 22, 4087. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22114087 (2022).

Park, M. H. et al. Effect of zr content on the wake-up effect in Hf1–xZrxO2 films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 15466–15475. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.6b03780 (2016).

Lenox, M. K., Jaszewski, S. T., Fields, S. S., Shukla, N. & Ihlefeld, J. F. Impact of Electric Field Pulse Duration on Ferroelectric Hafnium Zirconium Oxide Thin Film Capacitor endurance. Phys. Status Solidi A. 221, 2300566. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.202300566 (2024).

Cao, R. et al. Improvement of endurance in HZO-based ferroelectric capacitor using Ru electrode. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 40, 1744–1747. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2019.2937477 (2019).

Shao, X. et al. Investigation of endurance degradation mechanism of Si FeFET with HfZrO ferroelectric by an in situ Vth measurement. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 70, 3043–3050. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2023.3262482 (2023).

Lin, Y. D. et al. in. IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 6.4.1–6.4.4. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM19573.2021.9720710 (IEEE, 2021).

Kim, S. J. et al. Low-thermal-budget (300°C) ferroelectric TiN/Hf0.5Zr0.5O2/TiN capacitors realized using high-pressure annealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0058225 (2021).

Zhou, J. et al. Demonstration of ferroelectricity in Al-doped HfO2 with a low thermal budget of 500°C. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 41, 1130–1133. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2020.3001798 (2020).

Chiniwar, S. P. et al. Ferroelectric enhancement in a TiN/Hf1–xZrxO2/W device with controlled oxidation of the bottom electrode. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 6, 1078–1086. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.2c01434 (2024).

Lehninger, D. et al. Back-end-of-line compatible low-temperature furnace anneal for ferroelectric hafnium zirconium oxide formation. Phys. Status Solidi A. 217, 1900840. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201900840 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (No. 2020R1A2C1009063 and RS-2023-00260527). Also, this work was supported by Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd (IO230412-05900-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and C.S. conceived and designed all the experiments. Y.C. performed all the measurements. J.S., J.M., S.M., D.C., and D.H. participated in experimental works. Y.C., J.S., J.M., S.M., D.C., D.H., and C.S. discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, Y., Shin, J., Min, J. et al. Oxygen reservoir effect of Tungsten trioxide electrode on endurance performance of ferroelectric capacitors for FeRAM applications. Sci Rep 14, 28912 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80523-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80523-x