Abstract

To develop a clinical imaging method for monitoring macrophage migration to the defect site after implantation of various stem cells and evaluating immune responses in the context of knee arthritis, T2 mapping was correlated with CD68-positive cell densities in defects and the bone marrow. This study, which was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, used 32 New Zealand white rabbits preloaded with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles (USPIOs). They were divided into groups that received different stem cell implants after osteochondral defect induction. T2 imaging was performed using a 3.0 T MR scanner, and the data were analysed via one-way ANOVA, with CD68 expression assessed via immunohistochemistry. After implantation, the T2 signal intensity increased across groups, with subgroup D1 (implantation of rat bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs)) showing the lowest T2 value early and the steepest increase in T2 values. Notable differences in CD68-positive cell density were found between Subgroup D1 and the other groups and between Subgroups A1 and C1 post-surgery. A moderate negative correlation was observed between T2 signals and CD68-positive cell density in defects (r = -0.468, p = 0.001), whereas a weak correlation was detected in the bone marrow (r = 0.096, p = 0.313). A significant link was identified between CD68-positive cell density in the bone marrow and in defects (r = -0.255, p = 0.001). This study revealed significant differences in immune responses to stem cells from different origin tissues in the context of cartilage repair. Adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) were found to be more likely to provoke immune rejection than were BMSCs in the repair of femoral condyle cartilage defects. Compared with allogeneic transplants, xenogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplants were associated with prolonged immune rejection. T2 mapping technology was effective in predicting the density of CD68-positive cells, providing a valuable tool for immune monitoring in stem cell therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Degenerative arthritis, inflammatory arthritis, and trauma-induced osteochondral defects are the main causes of chronic joint pain and related disabilities. Owing to the limited self-regeneration capacity of cartilage, effective joint repair methods are needed1. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are important materials in the field of cell therapy and are commonly used in regenerative medicine. In animal models and human clinical trials, MSCs have been shown to effectively promote the repair of damaged tissues in various degenerative diseases2. In contrast to past proposals regarding the mechanisms by which transplanted MSCs promote tissue regeneration, such as transdifferentiation- or cell fusion-based mechanisms, it is now believed that MSCs efficiently release chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors that facilitate tissue regeneration through paracrine effects3. The therapeutic effect of MSCs depends on their homing ability and survival time after transplantation4.

Currently, treatment based on MSC transplantation faces various challenges, such as hypoxic conditions, an inflammatory local environment, and adverse effects including immune rejection5. In cases of transplant rejection, specific stem cell immune phenotypes attract various cell types, such as macrophages, T cells, and granulocytes, which recognize, kill, and eliminate the transplanted cells6.

Allogeneic and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-mismatched stem cell transplantation can trigger cytotoxic T-cell activation and macrophage responses, leading to acute or chronic allograft rejection7. In contrast to allogeneic stem cell transplantation, xenogeneic stem cell transplantation is associated with rejection mediated primarily by macrophages8. Monocytes and macrophages recognize “foreign” transplanted cells and release proinflammatory cytokines, leading to a vicious cycle of tissue inflammation, cell damage, and eventual death of the transplanted cells9. Recently developed immunomodulatory treatments can inhibit macrophage infiltration into allogeneic grafts10. To enhance the understanding of the processes involved in successful tissue regeneration, identify complications in the transplantation process, and monitor the response of transplanted cells to immunomodulatory treatments, it is necessary to develop imaging techniques that can be used to monitor the abovementioned interactions between stem cells and macrophages11. Although blood and serum analyses can detect markers of proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory responses in the body, they provide only indirect and nonspecific information about innate immune responses during stem cell transplantation.

Researchers have explored the use of preclinical imaging tools to detect immune responses to stem cell transplantation, track the long-term fate of labelled stem cells, and monitor the migration of T cells or macrophages to the graft12,13,14. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles, which are composed of small iron oxide particles coated with carbohydrates, can increase the relaxation rate of hydrogen spins in water molecules in the surrounding tissue, thereby significantly enhancing the contrast between the targeted area and the tissue background and providing measurable signal changes15. Specifically, when USPIOs are phagocytosed by macrophages or stem cells, a decrease in the MR signal can be detected on T2-weighted MR images16. This allows tracking of the fate of USPIO-labelled stem cells or direct monitoring of the degree of macrophage infiltration into the target tissue11.

In recent years, T2 mapping technology, which sets multiple TE values to more accurately measure T2 values in different regions, has emerged as a way to track changes in cellular infiltration17. This technology can effectively quantify the degree of immune rejection, facilitating early intervention to promote tissue repair. Therefore, this study aims to explore whether the immune rejection reactions and related inflammatory responses caused by the implantation of different types of matrix-associated stem cell implants (MASIs) can be dynamically observed and quantitatively analysed in vivo via T2 mapping and validated via pathology.

Methods

Cell culture

The protocol for the experiment involving rabbits was approved by the Experimental Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, under approval reference number DW2023063. One-month-old rats and 2-week-old rabbits were obtained from the Animal Center of Shanxi Medical University. All methods in this study were conducted with the permission of the Animal Ethics Committee and reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Rabbit bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs), rabbit adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), and rat BMSCs were extracted and cultured in complete growth medium. The culture medium was enriched with 10% foetal bovine serum, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin, all of which were sourced from the Procell Company in Wuhan, China. The cells were maintained under standard cell culture conditions in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with an atmospheric CO2 concentration of 5% (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1–5).

Development of a rabbit knee joint osteochondral defect model

The study included 32 New Zealand white rabbits, three months of age, which were obtained from the Shanxi Medical University Animal Center. These rabbits were randomly assigned to four groups, each comprising eight animals, and were labelled Groups A to D. Following induction of anaesthesia via intramuscular injection of ketamine at a dose of 0.1–0.2 mL/kg, USPIOs (uncoated, core particle size: 10 ± 5 nm) (Cat: SN-M-U11, SunLipo NanoTech, Shanghai, China) were administered intravenously through the marginal ear vein at a dose of 8.375 mg Fe/kg. Osteochondral defects with a diameter of 3 mm and a depth of 2 mm were carefully generated in the femoral intercondylar notch using a microdrill (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7).

The experimental design for Groups A to D involved distinct implantation strategies: Group A underwent single-hole implantation of rabbit BMSCs; Group B was subjected to double-hole implantation of rabbit BMSCs in both the superior and inferior cavities; Group C underwent double-hole implantation of rabbit ADSCs in the superior cavity and rabbit BMSCs in the inferior cavity; and Group D was subjected to implantation of rat BMSCs in the superior cavity and rabbit BMSCs in the inferior cavity. All the groups received stem cell-alginate microspheres, with the superior cavity labelled as number 1, the inferior cavity labelled as number 2, and the single cavity labelled as number 1, resulting in the formation of seven distinct subgroups (A1, B1, B2, C2, and D2: rabbit BMSC transplantation subgroups; C1: rabbit ADSC transplantation subgroup; D1: rat BMSC transplantation subgroup). The methodology for modelling is depicted in Supplementary Fig. 7, which illustrates the single-hole model. Groups B to D featured double holes with a 2 mm interhole distance. Postoperatively, prophylactic penicillin was administered weekly via intramuscular injection at a dose of 200,000 U per injection.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition

Images were obtained via scanning with a 3.0 T MR device (GE Discovery Silent 750W) using a clinical 16-channel wrist coil (WK426, Wankang). In a rigorously controlled experimental design, the rabbits stratified into Groups A through D underwent serial MRI scans at defined postoperative time points: 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks. At each designated time point, a cohort of two rabbits per group was subjected to MRI assessment of all four knee articulations, followed by euthanasia.

The animals were induced to enter a state of surgical anaesthesia via an intramuscular injection of ketamine at a dose of 0.1–0.2 mL/kg. Subsequently, the animals were placed in the prone position within a wrist coil, with careful attention given to aligning the knee joints centrally within the magnetic field of the MRI coil. The knee joints were maximally extended to ensure parallel alignment of the tibial longitudinal axis with the MRI imaging platform, optimizing the acquisition of transverse knee joint sections orthogonal to the tibial axis. This approach facilitated anatomical fidelity across serial imaging studies and maximized correlation with histological sectioning data (Supplementary Fig. 8).

The T2 mapping sequence was executed with the following technical specifications: a repetition time (TR) of 1700.0 ms, echo times (TEs) ranging from 14.4 to 115.4 ms in systematic increments, slice thickness set at 1.5 mm with an interslice gap of 0.2 mm, field of view (FOV) configured to 80.0 mm × 80.0 mm, matrix dimensions of 256.0 mm × 256.0 mm, and the number of excitations (NEX) set to 2.0.

Consistency in anatomical referencing was maintained by utilizing the same sagittal plane level in the T2 mapping sequence, such as a sagittal plane level at the maximal diameter of the patella or the central region of the femoral trochlea. Two trained radiologists delineated a 1 mm2 region of interest (ROI) on the T2 mapping pseudocolour map, performing quintuplicate measurements of T2 mapping signal intensities within the femoral intercondylar notch defect area, with the mean value being recorded for statistical analysis. Imaging at each postoperative interval was standardized to the same anatomical landmark to ensure comparability. The radiological assessment was conducted in a double-blinded fashion by two independent radiologists, thereby ensuring the integrity and precision of the measurements.

Histological assessment

After MRI at each specified postoperative time point was complete, the animals were killed via air embolization following intravenous ketamine overdose. The trochlea of each femur was carefully excised and fixed at 37 °C for 36 h by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde solution (Cat: P1110, Solarbio, Beijing, China). Following fixation, the samples were subjected to thorough rinsing under running water for one hour, after which they were immersed in a 10% EDTA decalcifying solution (Cat: E-IR-R112, Elabscience, Wuhan, China) for a duration of 60 days, with periodic solution replenishment every four days to ensure progressive decalcification. Once the decalcification process was complete, the specimens were sectioned at the periphery or centre of the osteochondral defect, ensuring comprehensive decalcification. The softened bone was then rinsed overnight to eliminate any residual decalcifying agents. The pH was subsequently carefully adjusted to neutral, and the samples were subjected to a systematic gradient alcohol dehydration protocol.

After dehydration, the samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned to a thickness of 4 µm for subsequent staining procedures. The sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (HE) (catalogue number: G1120; Solarbio, Beijing, China) to visualize the cellular structures. For immunohistochemical staining of CD68, a primary antibody specific for mouse CD68 was used at a dilution of 1:50 (catalogue number: ab955; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and detection was performed with a peroxidase/HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:1000 (catalogue number: E-AB-1001; Elabscience, Wuhan, China). HE staining was employed postoperatively to delineate the osteochondral defect area and the 1.5 cm region adjacent to the bone marrow cavity. An experienced pathologist carefully examined the CD68-stained tissue sections. To ensure the objectivity of the assessment and minimize bias, the evaluation was conducted under a blinded protocol. Specifically, the pathologist was blinded to the specific group assignments of the sections, including implant allocations and any data that could have influenced the evaluation. At 80× magnification, the pathologist randomly selected and assessed four osteochondral defect areas within a 1.5 cm radius, along with four adjacent regions on each section. To ensure the accuracy of the analysis and to prevent bias, areas containing bone trabeculae, osteoid, woven bone, and cartilage were carefully excluded from the assessment. This exclusionary criterion was implemented to prevent any distortion in the proportions of granulocytic and monocytic cells, thus avoiding potential false-positive or false-negative interpretations. An ImageJ image analysis system was used for detailed analysis of the images, the number of cd68-positive cells was calculated three times, and the average percentage was used as the final quantitative index for evaluation. The interpretation of the CD68 staining results is shown in Supplementary Figs. 9–13.

Statistical methodology

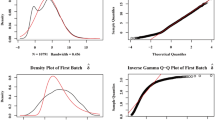

The experimental datasets were rigorously analysed utilizing the statistical software packages SPSS (26.0 version, 2019, IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) and Origin (2021 version, OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, Massachusetts, USA) and the digital image processing program ImageJ (2021 version, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Quantitative data with a normal distribution are expressed as the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation. One-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences across multiple groups. In instances where no interaction was detected between time points and group categorizations, the least significant difference (LSD) t test was applied for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Conversely, when interactions were observed between the time points and group categorizations, a simple effects analysis employing the least significant difference (LSD) method was conducted for pairwise comparisons of the interaction terms (time points × groups). Qualitative data are presented as relative frequencies, and group comparisons were performed via the chi-square test. For data adhering to a normal distribution, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the strength and direction of the linear relationship. The threshold for statistical significance was set at α = 0.05, with P values less than 0.05 indicating statistically significant differences.

Results

T2 Mapping to Assess Immune Rejection Following Matrix-Associated Stem Cell Implantation in Rabbit Knee Joint Osteochondral Defects.

The raw postoperative T2 mapping images captured at TE = 14.4 ms in Groups A–D revealed one or two localized defects in the femoral trochlea of the rabbit knee joints, each accompanied by an internal circular or oval-shaped implant. These implants presented signal intensities slightly higher than those of the surrounding bone tissue, with occasional punctate mixed signal shadows and articular cartilage fracture layers at the periphery. Over the period from two days to four weeks postsurgery, the defects in Groups A-D were gradually filled with reparative tissue, the fracture planes became increasingly smooth, and the signal exhibited varying degrees of change, with particularly significant differences observed between the two-day postoperative time point and subsequent time points.

In postprocessed T2 mapping images, some vascular or fluid-filled areas exhibited an absence of pseudocolour signals. The femoral trochlea showed circular or oval-shaped osteochondral defects, each containing spherical or oval-shaped implants with signal intensities markedly different from those of the adjacent tissue, and clear demarcations from the surrounding cartilage and bone. Multiple regions of interest (ROIs) were selected for measurement, and the average values were determined. These postprocessed images were then superimposed on the original images to create composite images (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15).

The pseudocolour signal intensity range in the composite T2 mapping images at TE = 14.4 ms was set between 25 and 75 ms. From two days to one week postsurgery, there was a variable increase in signal intensity across Groups A–D, with the most notable increase observed in Group D. From two days to four weeks postsurgery, the defects gradually diminished in size and became flatter. Differences of varying magnitude were observed between the two holes in Groups B–D, with the most significant differences noted in Group D. At the two-day postoperative time point, the signal intensity of the murine BMSC composite implant in Subgroup D1 was lower, with an orange‒red colour, and significantly different from the signal intensities of the other subgroups; the signal intensities in Subgroups D2 and C1 also showed some differences compared with those of the other subgroups (Fig. 2).

Superimposed T2 mapping images show the signal values at different time points after MASI surgery. Group A received a single hole, groups B–D received a double hole, with the upper hole designated hole 1 and the lower hole designated hole 2. A1, B1, B2, C2, and D2: rabbit BMSC transplantation subgroups; C1: rabbit ADSC transplantation subgroup; D1: rat BMSC transplantation subgroup.

The statistical analysis of the T2 mapping signal values of the osteochondral defects following MASI surgery in the seven subgroups confirmed that the data adhered to a normal distribution with uniform variance. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant difference in the T2 mapping signal values among the subgroups at two days after surgery (F = 5.418, P = 0.002 < 0.05). Beyond this early stage, no significant disparities were noted at the one-week, two-week, and four-week time points (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs. 16 and 19).

The intergroup effect analysis substantiated this significant variation (F intergroup = 17.542, P = 0.001 < 0.05), highlighting the differential impact of MASI implantation on T2 mapping signal values across the subgroups. The intragroup effect analysis revealed a significant temporal trend in the T2 mapping signal values (F intragroup = 5.860, P = 0.001 < 0.05). However, the interaction effect between the temporal trend and the influence of MASI implantation across the subgroups was not statistically significant (F interaction = 0.105, P = 1.000 > 0.05).

When the least significant difference (LSD) test for post hoc multiple comparisons was used, a significant difference in signal values at the two-day postoperative time point was observed between Subgroup D1 and the remaining subgroups (P < 0.05). Subgroup A1 also exhibited significant differences compared with Subgroups C1 and D2 (P < 0.05). At the one-week postoperative time point, Subgroup D1 exhibited significant differences in signal values relative to those of Subgroups A1, B1, B2, and C2 (P < 0.05). At the two-week postoperative time point, Subgroup D1 presented significant differences in signal values compared with those of Subgroup A1 (P < 0.05). Similarly, at the four-week postoperative time point, Subgroup D1 presented significant differences in signal values compared with those of Subgroup A1 (P < 0.05).

Intragroup comparisons within Subgroups A1, B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2 across the two-day, one-week, two-week, and four-week postoperative intervals failed to reveal any statistically significant differences (P > 0.05).

Histological evaluation

Proportion of CD68-positive cells in the defect after MASI implantation in the seven subgroups at different time points

The proportions of CD68-positive cells in the osteochondral defects post-MASI implantation in the seven subgroups adhered to a normal distribution and exhibited homogeneity of variance. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed statistically significant differences in the proportions of CD68-positive cells among the subgroups at the two-day, one-week, two-week, and four-week postoperative time points (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 17 and 20).

CD68 immunohistochemical staining results for osteochondral defect areas in seven different subgroups at various time points following MASI implantation. The specific groups are as follows: A1, B1, B2, C2, and D2 are subgroups subjected to rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation; C1 is a subgroup subjected to rabbit ADSC transplantation; and D1 is a subgroup subjected to rat BMSC transplantation. The figure shows the distribution of CD68-positive cells in the osteochondral defect areas. These CD68-positive cells appear brown after DAB staining, which contrasts sharply with the blue colour of haematoxylin-stained nuclei.

Intragroup effect analysis revealed a pronounced time-dependent trend in CD68-positive cell proportions (F intragroup = 47.148, P < 0.001). Intergroup effect analysis revealed significant variability in the impact of MASI implantation on CD68-positive cell proportions across the subgroups (F intergroup = 638.273, P < 0.001). The interaction between temporal trends and the effects of MASI implantation was statistically significant (F interaction = 36.315, P < 0.001), warranting the use of simple effects analysis.

When the LSD method for simple effects analysis was used, significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions were observed at the two-day postoperative timepoint between Subgroup D1 and the other subgroups, as well as between Subgroup A1 and Subgroup C1 (P < 0.05). At the one-week postoperative time point, subgroup D1 presented significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions compared with those of all other subgroups, with subgroup A1 showing significant differences compared with subgroup C1 (P < 0.05). At the two-week postoperative time point, subgroup D1 presented significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions compared with those of subgroups A1, B1, B2, C2, and D2, and subgroup A1 presented significant differences compared with subgroup C1 (P < 0.05). At the four-week postoperative time point, subgroup D1 presented significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions compared with those of subgroups A1 and B1, and subgroup A1 presented significant differences compared with subgroups B2 and C1 (P < 0.05).

Within each subgroup (A1, B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2), the intragroup comparisons across the postoperative time points consistently revealed statistically significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions (P < 0.05), with a clear overall decreasing trend.

Proportion of CD68-positive cells near the bone marrow cavity after MASI Implantation in seven subgroups at different time points

The proportion of CD68-positive cells in the bone marrow cavity adjacent to the osteochondral defects across the seven subgroups conformed to a normal distribution with a homogeneous variance. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no statistically significant differences in CD68-positive cell proportions among the subgroups at the two-day, one-week, two-week, and four-week postoperative time points following MASI implantation (P > 0.05) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. 18 and 21 and Supplementary Table 3).

CD68 immunohistochemical staining results of the adjacent bone marrow lumen in seven different subgroups at various time points following MASI implantation. The specific groups are as follows: A1, B1, B2, C2, and D2 are subgroups subjected to rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation; C1 is a subgroup subjected to rabbit ADSC transplantation; and D1 is a subgroup subjected to rat BMSC transplantation. The figure shows the distribution of CD68-positive cells in the adjacent bone marrow lumen. These CD68-positive cells appear brown after DAB staining, which contrasts sharply with the blue colour of haematoxylin-stained nuclei.

Intragroup effect analysis revealed a significant temporal trend in the proportion of CD68-positive cells adjacent to the surgical site (F intragroup = 3.981, P = 0.012 < 0.05). Conversely, intergroup effect analysis did not reveal any statistically significant differences (F intergroup = 0.873, P = 0.531 > 0.05), implying uniformity in the influence of MASI implantation on CD68-positive cell proportions in the adjacent bone marrow cavity among the subgroups. The interaction effect between temporal trends and the impact of MASI implantation was also not statistically significant (F interaction = 0.071, P = 1.000 > 0.05).

When the LSD method was employed for pairwise comparisons at the specified postoperative time points, no statistically significant differences were detected among Subgroups A1, B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2 (P > 0.05).

Similarly, intragroup comparisons within each subgroup (A1, B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and D2) across the two-day, one-week, two-week, and four-week postoperative time points failed to reveal any statistically significant differences (P > 0.05).

Relationship between T2 mapping signal values and the proportion of CD68-positive cells in the defect and bone marrow cavity

An overlapping scatter plot was generated to visualize the relationship between the T2 mapping signal values post-MASI implantation in the seven subgroups and the proportions of CD68-positive cells in the adjacent bone marrow cavity and at the defect site. The plots essentially exhibited a linear correlation pattern. The correlation coefficient for the relationship between T2 mapping signal values and the proportion of CD68-positive cells at the defect site was calculated to be -0.468, with a significant Sig value of 0.001, indicating a statistically significant low negative correlation. Conversely, the correlation coefficient for the relationship between T2 mapping signal values and the proportion of CD68-positive cells in the bone marrow cavity was negligible at 0.096, with a Sig value of 0.313, suggesting that there was no significant association (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 4).

Furthermore, a significant weak negative correlation was observed between the proportions of CD68-positive cells in the bone marrow cavity and at the defect site, with a correlation coefficient of -0.255 and a Sig value of 0.001, indicating a pronounced yet weak inverse relationship between these two variables. These findings underscore the potential of T2 mapping as an imaging biomarker for predicting the immune response in the context of stem cell implantation therapies.

Discussion

Evaluation of the experimental results

Intravenous injection of MSCs is a commonly used technique for stem cell transplantation. Postinfusion, however, a significant portion of MSCs are likely to be carried to the lungs via the bloodstream and are subsequently cleared by resident macrophages in peripheral tissues within a short time frame18. In addition to intravenous injection, alternative and widely adopted methods for MSC transplantation include intra-articular injection, subchondral bone injection, and the use of MSC-seeded scaffolds for implantation19. Throughout the implantation phase, the paracrine and autocrine mechanisms of MSCs are instrumental in preventing cell apoptosis and tissue fibrosis while also stimulating angiogenesis and driving cell mitosis through the release of growth factors. These effects collectively promote tissue repair, sustain tissue vitality, potentially arrest the progression of osteoarthritis, and improve associated clinical parameters and clinical manifestations20.

In the context of allogeneic transplantation, disparities in HLA antigens between the donor and recipient have been identified as the principal causes of immune rejection, which may lead to severe complications such as implant failure, late-stage rejection reactions, and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)21. Immune rejection in the context of allogeneic transplantation is predominantly mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which activate monocytes in the bloodstream and differentiate into inflammatory macrophages within the inflammatory local environment, thereby initiating an inflammatory response in the allogeneic graft22.

Xenogeneic transplantation faces the challenge of immune rejection, primarily due to the mismatch of α-Gal antigens between the donor and recipient, culminating in transplant failure23. Histopathological research has shown that the mechanisms underlying xenogeneic transplant rejection markedly differ from those underlying allogeneic rejection, with the former predominantly involving the infiltration of NK cells and macrophages, in contrast to the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-driven rejection observed in allogeneic scenarios24. Macrophages are recognized for their crucial role in the oxidative stress and inflammatory responses initiated by xenogeneic transplantation25. This study revealed that at early postoperative time points, there was notable variation in the proportion of CD68-positive cells within the postoperative defect area when comparing the implantation of rat BMSCs to that of rabbit BMSCs or ADSCs. Similarly, at later postoperative time points, a significant difference was observed between the implantation of rat BMSCs and that of rabbit BMSCs in terms of the proportion of CD68-positive cells within the defect area. These findings suggest that the degree of macrophage infiltration associated with the xenogeneic transplantation of rat BMSCs into the osteochondral defect area in the rabbit knee joint surpasses that associated with allogeneic transplantation and that the immune rejection response elicited by xenogeneic cell transplantation may persist for an extended period.

At an early postoperative time point, variations in the proportions of CD68-positive cells within the postoperative defect area were noted after implantation of different stem cell types, underscoring the potential for diverse immune responses even within the same species and across stem cells derived from different tissues. These observations corroborate previous findings that highlighted the varying immunogenicity of ADSCs and BMSCs at the osteochondral defect site26.

In summary, the capacity of allogeneic grafts to prevent immune rejection is a subject of ongoing debate21. USPIOs, which are utilized as a T2 contrast agent in MRI, are instrumental in the acceleration of T1 and T2/T2* relaxation processes. Once introduced into the body via intravenous injection, USPIOs are taken up by phagocytic cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and oligodendrocytes, making their presence detectable via MRI scans27. Notably, not only are macrophages, which are known for their strong phagocytic activity and are suitable for labelling, but also T cells and neutrophils can be marked for cell tracking and tumour-specific imaging studies28. This allows researchers to trace the migration of these cells or to employ these labels for enhanced precision in imaging and localization in the context of cancer diagnosis and treatment29. Empirical evidence from some experiments has confirmed that quantitative imaging based on T2 mapping is an indirect method for quantifying iron concentrations, thereby allowing the estimation of macrophage counts and proportions30. These methodological breakthroughs in imaging have paved the way for noninvasive surveillance of the immune responses that may arise following MSC treatment.

In this study, we selected an intravenous dose of 8.375 mg Fe/kg, which is equivalent to approximately 500 micromolar USPIOs/kg, to strike a balance between ensuring ample macrophage uptake of USPIOs and achieving the most favourable imaging results. This dose was chosen after considering a multitude of factors that can affect the performance of USPIOs in imaging, including the type of coating on the USPIOs, their distribution and clearance rates postinjection, pharmacokinetic properties, the efficacy of cellular phagocytosis, and potential issues such as particle aggregation or cellular compartmentalization31,32,33. This approach is designed to optimize the visualization of macrophages via MRI, providing clearer and more detailed images for diagnostic and research purposes.

Different MRI sequences exhibit varying sensitivity to USPIOs, with prior research indicating that T2 mapping sequences are particularly sensitive in detecting iron-related signal changes34,35. Moreover, T2 mapping sequences have shown good repeatability and stability when utilized in the musculoskeletal region34,35. Consequently, in this study, we employed quantitative imaging based on T2 mapping to scrutinize the relationship between signal intensity and macrophage activity, with the aim of noninvasively investigating the interactions between various stem cell types, inflammatory microenvironments, and macrophages. The observed data revealed a statistically significant strong negative correlation between T2 mapping signal values and the proportion of CD68-positive cells at the site of the defect, with a correlation coefficient of -0.468 and a significant p value. This correlation underscores the utility of T2 mapping in predicting and quantifying the initial macrophage migration induced by the implantation of rat BMSCs into an osteochondral defect in the rabbit knee joint, offering insights into the inflammatory status of the wound and the associated immune responses, whether allogeneic or xenogeneic, that can be induced by stem cell transplantation.

Within the confines of this study, the variation in CD68-positive cell proportions between single-hole osteochondral defects and double-hole osteochondral defects in the experimental animals did not reach statistical significance. Nonetheless, an increased proportion of CD68-positive cells was noted in the postoperative defect areas of the double-hole subgroup compared with those of the single-hole subgroup. This correlation may indicate a direct relationship between the severity of trauma and the extent of macrophage infiltration. The discrepancies in wound dimensions and inflammatory responses could marginally affect the macrophage population responsible for modulating the immunological milieu. These findings are in line with existing research, which holds that there is an interaction between MSCs and the inflammatory microenvironment, with the characteristics of the inflammatory microenvironment influencing the immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory functions of MSCs36.

At the two-week and four-week postoperative time points, significant differences in T2 mapping signal values were observed between the D1 subgroup that received rat BMSCs and the A1 subgroup that received rabbit BMSCs. Furthermore, differences in the proportions of CD68-positive cells at the defect site were noted between the D1 subgroup and other subgroups (non-C1 subgroups). We believe that the lack of consistency in the T2 mapping signal values and the proportions of CD68-positive cells may be due to the influence of granulation tissue and fibrous repair at the defect site on the quantification of immune rejection by T2 mapping.

In a study by Daldrup-Link and Nejadnik10, viable and apoptotic ADSCs were implanted into bone and cartilage defects. All MASI types resulted in a gradual decline in the T2 signal within 4 weeks post-implantation, with the SNR values of the apoptotic implants significantly decreasing over time. This was confirmed to correspond to the differential migration of iron-loaded macrophages towards the MASI11.

Daldrup later employed ADSCs that were matched and mismatched with respect to sex and species, implanting them into calvarial defects in rats, and demonstrated that the immunologically mismatched MASIs resulted in notably diminished signal intensity at the four-week postoperative time point compared with that of the matched MASIs37. This observation stands in contrast to the outcomes of our experiments, and we believe that several factors may be related to this discrepancy. Initially, we used rabbits with normal immune function, whereas Daldrup selected athymic nude rats, which may account for the absence of T-cell-mediated immunological processes such as macrophage activation in T-cell-deficient nude rats. Subsequently, the SNR value, which is calculated on the basis of the conventional T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) sequence formula, might differ from the methodology employed for T2 mapping signal values in our study11. Finally, Daldrup opted for the administration of 0.5 mmol/kg ferumoxytol (30 nm, Cambridge, Massachusetts) two days preoperatively, with MRI conducted on the day of surgery. Conversely, our experimental protocol involved the intraoperative injection of USPIOs (uncoated, core particle size of 10 ± 5 nm) (Cat: SN-M-U11, SunLipo NanoTech, Shanghai, China), followed by an initial MR scan two days postoperatively. Given that USPIOs of varying particle sizes circulate to distinct regions via the bloodstream and are phagocytosed by different types of phagocytic cells at different rates, the disparities in experimental materials and procedures could result in divergent nanoiron burdens within macrophages that migrate to inflammatory or immune rejection environments, leading to variations in the T2 mapping signals detected at different time points, which could explain the divergence of our experimental findings from those of Daldrup11,37.

The proportion of CD68-positive cells in the bone marrow adjacent to the defect site significantly increased over time within the same cohort, suggesting that the bone marrow cavity persistently releases inflammatory mediators throughout the four-week postoperative period, drawing in principal inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages to engulf necrotic tissues and cellular debris.

Limitations and shortcomings

The findings of this study suggest that T2 mapping values may be associated with the inflammatory environment adjacent to the wound, the degree of immune rejection, and the presence of macrophages. However, its limitations include the influence of postoperative bleeding, residual metal debris from drilling, granulation tissue repair, and fibrous repair on T2 values.

While the relaxivity or signal value of USPIOs in solution is linearly related to the concentration of USPIOs, the relaxivity may change when the particles are internalized by cells due to aggregation or cellular compartmentalization33,38. This makes direct quantification of the local iron concentration in tissues difficult. Although USPIOs are associated primarily with macrophages, the local iron concentration is not a direct measure of the number of macrophages. Instead, it is influenced by various factors, including the content, subtype, and activity of macrophages; the inflammatory environment caused by wounds of different sizes; the immune environment established by different types of MSCs; and the effects of the pharmacokinetics of the contrast agent.

CD68, a marker for macrophages, may not be highly specific and could produce some false positives, thereby affecting the ability to accurately assess the proportion of macrophages. In this study, we did not choose more specific M1- or M2-type macrophage markers to explore the relationship between the proportions of different types of macrophages at different time points.

In addition, the small sample size may mean that the results do not accurately reflect the significance of differences among groups.

These issues all need to be considered and addressed in future studies to increase the accuracy and credibility of our findings.

Prospects and future plans

In the future, the baseline levels of monocytes and macrophages attracted to each type of wound should be explored more comprehensively, and increasing the sample size can improve the precision of T2 mapping in quantifying the degree of immune rejection, thereby enabling the prediction of bone and cartilage repair.

Furthermore, investigating the immunoregulatory function of MSCs in different inflammatory environments is also important. For example, the decision of whether to select athymic animals for the experiment was related to T cell functions. Crosstalk between mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages in the context of different levels of inflammation was observed to involve inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF-α.

The use of more specific antibodies, such as antibodies specific for CD206 and F4/80, to explore the relationships between the proportions of different types of macrophages at different time points and immune rejection, immune tolerance, immune regulation, and bone and cartilage repair will help to elucidate the mechanism of action of macrophages in this process.

Conclusion

This study revealed the differential immune responses elicited by stem cells from various tissue sources in cartilage repair. These findings indicate that ADSCs are more prone to induce macrophage-mediated immune rejection than are BMSCs in the repair of femoral condyle cartilage defects. Moreover, xenogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation elicits stronger immune rejection responses than allogeneic cell transplantation does, and these responses may persist for several weeks. These insights underscore the need to assess potential immune responses prior to stem cell transplantation.

T2 mapping technology has been demonstrated to have high accuracy in predicting the proportion of CD68-positive cells, offering an effective tool for monitoring microenvironmental changes during wound healing. This research provides new perspectives for optimizing stem cell therapy strategies and introduces novel approaches for immune monitoring.

Data availability

Due to the shared protocol of this research group, the data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

06 March 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article the Supplementary Information file, some images were not displayed. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Hunter, W. Of the structure and disease of articulating cartilages. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 317, 3–6 (1995).

Selvasandran, K. et al. A tumor necrosis factor-α and hypoxia-induced secretome therapy for myocardial repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 105, 715–723 (2018).

Folestad, E., Kunath, A. & Wagsater, D. PDGF-C and PDGF-D signaling in vascular diseases and animal models. Mol. Aspects Med. 62, 1–11 (2018).

Lin, W. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells homing to improve bone healing. J. Orthop. Translat. 9, 19–27 (2017).

Toma, C., Wagner, W. R., Bowry, S., Schwartz, A. & Villanueva, F. Fate of culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells in the microvasculature: In vivo observations of cell kinetics. Circ. Res. 104, 398–402 (2009).

Karabekian, Z., Posnack, N. G. & Sarvazyan, N. Immunological barriers to stem-cell based cardiac repair. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 7, 315–325 (2011).

Ikezumi, Y., Hurst, L. A., Masaki, T., Atkins, R. C. & Nikolic-Paterson, D. J. Adoptive transfer studies demonstrate that macrophages can induce proteinuria and mesangial cell proliferation. Kidney Int. 63, 83–95 (2003).

Nilsson, B., Korsgren, O., Lambris, J. D. & Ekdahl, K. N. Can cells and biomaterials in therapeutic medicine be shielded from innate immune recognition?. Trends Immunol. 31, 32–38 (2010).

English, K. & Wood, K. J. Mesenchymal stromal cells in transplantation rejection and tolerance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 3, a015560 (2013).

Daldrup-Link, H. E. & Nejadnik, H. MR imaging of stem cell transplants in arthritic joints. J. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 4, 165 (2014).

Khurana, A. et al. Intravenous ferumoxytol allows noninvasive MR imaging monitoring of macrophage migration into stem cell transplants. Radiology 264, 803–811 (2012).

Kim, D. E. et al. Neural stem cell transplant survival in brains of mice: Assessing the effect of immunity and ischemia by using real-time bioluminescent imaging. Radiology 241, 822–830 (2006).

Cahalan, M. D. Imaging transplant rejection: A new view. Nat. Med. 17, 662–663 (2011).

Christen, T. et al. Molecular imaging of innate immune cell function in transplant rejection. Circulation 119, 1925–1932 (2009).

Poon, I. K., Lucas, C. D., Rossi, A. G. & Ravichandran, K. S. Apoptotic cell clearance: Basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 166–180 (2014).

Khurana, A. et al. Ferumoxytol: A new, clinically applicable label for stem-cell tracking in arthritic joints with MRI. Nanomedicine (Lond) 8, 1969–1983 (2013).

Andreisek, G. & Weiger, M. T2* mapping of articular cartilage: Current status of research and first clinical applications. Invest. Radiol. 49, 57–62 (2014).

Rikhtegar, R. et al. Stem cells as therapy for heart disease: iPSCs, ESCs, CSCs, and skeletal myoblasts. Biomed. Pharmacother. 109, 304–313 (2019).

Wei, P. & Bao, R. Intra-articular mesenchymal stem cell injection for knee osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and clinical evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 59 (2022).

Molnar, V. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell mechanisms of action and clinical effects in osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Genes 13, 949 (2022).

Kot, M. et al. The importance of HLA assessment in “off-the-shelf” allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells based-therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5680 (2019).

Afzali, B., Lombardi, G. & Lechler, R. I. Pathways of major histocompatibility complex allorecognition. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 13, 438–444 (2008).

Ide, K. et al. Role for CD47-SIRPalpha signaling in xenograft rejection by macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 5062–5066 (2007).

Fox, A., Mountford, J., Braakhuis, A. & Harrison, L. C. Innate and adaptive immune responses to nonvascular xenografts: Evidence that macrophages are direct effectors of xenograft rejection. J. Immunol. 166, 2133–2140 (2001).

Maeda, A. et al. The innate cellular immune response in xenotransplantation. Front. Immunol. 13, 858604 (2022).

Oh, S. et al. Comparative analysis on the anti-inflammatory/immune effect of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci. Rep. 11, 2012 (2021).

Jin, W. N. et al. Non-invasive tracking of CD4+ T cells with a paramagnetic and fluorescent nanoparticle in brain ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 36, 1464–1476 (2016).

Kirschbaum, K. et al. In vivo nanoparticle imaging of innate immune cells can serve as a marker of disease severity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 13227–13232 (2016).

Thorek, D. L. & Tsourkas, A. Size, charge and concentration dependent uptake of iron oxide particles by non-phagocytic cells. Biomaterials 29, 3583–3590 (2008).

Moonen, R. P. M., Coolen, B. F., Sluimer, J. C., Daemen, M. & Strijkers, G. J. Iron oxide nanoparticle uptake in mouse brachiocephalic artery atherosclerotic plaque quantified by T2-mapping MRI. Pharmaceutics 13, 279 (2021).

Bull, E. et al. Stem cell tracking using iron oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomedicine 9, 1641–1653 (2014).

Jeon, M., Halbert, M. V., Stephen, Z. R. & Zhang, M. Iron oxide nanoparticles as T(1) contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging: Fundamentals, challenges, applications, and prospectives. Adv. Mater. 33, e1906539 (2021).

Hak, S., Goa, P. E., Stenmark, S., Bjerkholt, F. F. & Haraldseth, O. Transverse relaxivity of iron oxide nanocrystals clustered in nanoemulsions: Experiment and theory. Magn. Reson. Med. 74, 858–867 (2015).

Ghassaban, K., Liu, S., Jiang, C. & Haacke, E. M. Quantifying iron content in magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 187, 77–92 (2019).

Amirabadi, A. et al. USPIO-related T1 and T2 mapping MRI of cartilage in a rabbit model of blood-induced arthritis: A pilot study. Haemophilia 21, e59–e69 (2015).

Ren, G. et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell 2, 141–150 (2008).

Daldrup-Link, H. E. et al. Detection of stem cell transplant rejection with ferumoxytol MR imaging: Correlation of MR imaging findings with those at intravital microscopy. Radiology 284, 495–507 (2017).

Lévy, M., Wilhelm, C., Devaud, M., Levitz, P. & Gazeau, F. How cellular processing of superparamagnetic nanoparticles affects their magnetic behavior and NMR relaxivity. Contrast. Media Mol. Imaging 7, 373–383 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82172011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang Wenhui is responsible for the conception, first draft writing and review of the paper. Zhu Jiahong is in charge of data curation, Liu Zhenyu is in charge of project administration, Zhen haocheng was responsible for statistical analysis and revision, Qi Meiling is in charge of visualization, Luo Jing is in charge of resources, and Zhen Junping is in charge of funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Liu, Z., Zhu, J. et al. Macrophage tracking with USPIO imaging and T2 mapping predicts immune rejection of transplanted stem cells. Sci Rep 14, 29162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80750-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80750-2