Abstract

Enhanced technologies of the future are gradually improving the digital landscape. Internet of Things (IoT) technology is an advanced technique that is quickly increasing owing to the development of a network of organized online devices. In today’s digital era, the IoT is considered one of the most robust technologies. However, attackers can effortlessly hack the IoT devices employed to generate botnets, and it is applied to present distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks beside networks. The DDoS attack is the foremost attack on the system that causes the complete network to go down. Thus, average consumers may need help to get the services they need from the server. The compromised or attackers IoT devices want to be perceived well in the system. So, presently, Deep Learning (DL) plays a prominent part in forecasting end-users’ behaviour by extracting features and identifying the adversary in the network. This paper proposes a Synergistic Swarm Optimization and Differential Evolution with Graph Convolutional Network Cyberattack Detection and Mitigation (SSODE-GCNDM) technique in the IoT environment. The main intention of the SSODE-GCNDM method is to recognize the presence of DDoS attack behaviour in IoT platforms. Primarily, the SSODE-GCNDM technique utilizes Z-score normalization to scale the input data into a uniform format. The presented SSODE-GCNDM approach utilizes synergistic swarm optimization with a differential evolution (SSO-DE) approach for the feature selection. Moreover, the graph convolutional network (GCN) method recognizes and mitigates attacks. Finally, the presented SSODE-GCNDM technique implements the northern goshawk optimization (NGO) method to fine-tune the hyperparameters involved in the GCN method. An extensive range of experimentation analyses occur, and the outcomes are observed using numerous features. The experimental validation of the SSODE-GCNDM technique portrayed a superior accuracy value of 99.62% compared to existing approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

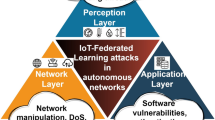

The industrialized achievement of the IoT presents various military and civilian applications for developing the connectivity of millions of novel smart devices. These millions of risky internet-connected smart devices cause a dangerous security risk in the existence of uncountable cyberattacks. These insecurely protected devices are the doorways for hackers’ intrusion and cause problems with the industrialized achievement of IoT1. These IoT-prepared devices devise hotspots for attackers to initiate volumetric attacks in the system of Denial-of-Service (DoS), Distributed DoS (DDoS), spamming, click fraud, etc. Among these cyberattacks, DDoS is the most well-known attack created with the help of botnets equipped with unprotected IoT devices2. DDoS attacks are often undergone owing to the development of botnets that affect millions of IoT devices. DDoS security attacks constantly threaten organizations and individual and company service providers. A DDoS attack utilizes various computers to unveil the distributed attack against one or more targets. The dispersed nature of the attack upsurges its actual ability and is very hard to identify3. Figure 1exemplifies the general structure of DDoS attacks in IoT platforms. With the developments of cloud computing (CC), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and IoT, attackers could launch huge-scale DDoS attacks at a lower cost. It is very challenging to identify and protect DDoS attacks. In many cases, DDoS network traffic is comparable to the usual one4. Thus, identifying and detecting DDoS from massive network traffic is challenging. Many standard mechanisms to identify and inhibit DDoS include attack reaction, attack prevention, and attack detection. Network intrusion detection system (NIDS) has become an essential module of security creation5.

It identifies unusual system utilization by observing and analyzing the behaviour of a system to identify the attack. There are dual kinds of NIDS, specifically, Anomaly-based NIDS and Signature-based NIDS. Signature-based recognition identifies attacks by gathering and identifying whether there is a particular signature or pattern of previous attacks in traffic. However, it could be more effective in DDoS attack recognition because attackers frequently change the methods and kinds of attacks. Therefore, it is challenging to identify the signature or pattern of an attack6. When a DDoS attack arises on a system, the related traffic will result in unusual system behaviour. Therefore, NIDS could attain the equivalent attacks. To overwhelm the limits of these dual techniques, hybrid solutions based on either Anomaly-based or Signature-based methods are presented7. Research has presented numerous methods for handling DDoS attacks. The common methods utilize multiple machine learning (ML) methods to conquer DDoS attacks. Furthermore, hybrid solutions that integrate the two or more ML methods are presented. ML models are measured to be a feasible method of identifying DDoS attacks. These methods study the patterns behind attacks to identify them before network resources become inaccessible8. Current security methods use ML and other detection methods containing host-based IDS (HIDS) and IDS to respond to intricate cyber-attacks like DDoS attacks efficiently. The rapid proliferation of smart devices in diverse sectors has created unprecedented opportunities for innovation, but it also exposes critical vulnerabilities in network security9. As these interconnected devices become integral to daily operations, the potential for cyber threats, specifically DDoS attacks, intensifies. These attacks can disrupt services and compromise sensitive data, resulting in substantial financial and operational losses. Therefore, enhancing detection and mitigation strategies for such threats is crucial to safeguard the integrity of IoT ecosystems. Addressing these threats protects organizations and fosters trust in the ongoing adoption of smart technologies10.

This paper proposes a Synergistic Swarm Optimization and Differential Evolution with Graph Convolutional Network Cyberattack Detection and Mitigation (SSODE-GCNDM) technique in the IoT environment. The main intention of the SSODE-GCNDM method is to recognize the presence of DDoS attack behaviour in IoT platforms. Primarily, the SSODE-GCNDM technique utilizes Z-score normalization to scale the input data into a uniform format. The presented SSODE-GCNDM approach utilizes synergistic swarm optimization with a differential evolution (SSO-DE) approach for the feature selection. Moreover, the graph convolutional network (GCN) method recognizes and mitigates attacks. Finally, the presented SSODE-GCNDM technique implements the northern goshawk optimization (NGO) method to fine-tune the hyperparameters involved in the GCN method. An extensive range of experimentation analyses occur, and the outcomes are observed under numerous features. The major contribution of the SSODE-GCNDM technique is listed below.

-

The SSODE-GCNDM model employs Z-score normalization to standardize input data, which improves the technique’s performance and stability. This approach allows for improved comparability among features, ultimately enhancing the overall efficiency of the model. Confirming that data is uniformly scaled eases more accurate training and evaluation.

-

The SSODE-GCNDM technique utilizes the SSO-DE for efficient feature selection, substantially improving the chosen features’ relevance. This methodology allows the model to concentrate on the most impactful data, enhancing its predictive accuracy. Employing the merits of both optimization methods effectively streamlines the feature selection process.

-

The SSODE-GCNDM method effectively utilizes the GCN model to detect and reduce potential attacks, integrating the merits of graph-based learning. This enables the model to capture intrinsic relationships within the data, resulting in enhanced detection accuracy. By employing GCN, the technique improves its capability to detect patterns indicative of attacks, thereby strengthening overall safety measures.

-

The SSODE-GCNDM technique implements the NGO method to fine-tune hyperparameters in the GCN, resulting in improved model performance and precision. This optimization method assists in systematically exploring the hyperparameter space, resulting in more effective learning results. By enhancing the tuning process, the technique substantially improves the capability of the GCN model to handle complex attack scenarios.

-

Incorporating SSO-DE for feature selection and NGO for hyperparameter tuning within a GCN framework underscores a novel and cohesive strategy for improving attack detection accuracy. This novel integration employs the merits of diverse optimization techniques, confirming both relevant feature detection and optimal model performance. By synergizing these methods, the approach enhances detection rates and sets a new standard for tackling complex security threats in network data analysis.

Review of literature

Sanlı11 proposes a novel approach for mitigating and detecting DoS attacks in IoT systems. The presented technique is executed on an FPGA-based platform and tested for performance against various DoS attacks. Abid et al.12present a new technique for identifying and classifying DDoS attacks, which is enhanced significantly for this atmosphere. As part of the method, the author incorporates CNNs and LSTM methods into a multi-level deep neural network (DNN) model. With this hybrid structure, intricate temporal and spatial forms are spontaneously extracted from raw network traffic data to enable the widespread study and precise recognition of DDoS attacks. Kumar and Kumar Keshri13 developed a smart GT-AS numerical method to maximize the DDoS attack mitigation efficiency. Furthermore, this tactic could intensely develop the five parameters: memory, intruder, hybrid, and energy channel. These could attain a strong security position against DDoS attacks from the recently devised IoT. Subsequently, the RB method is advanced to categorize the nodes into dual classes, such as malicious and trusted. Furthermore, the presented methods analyze how defence efficiency and energy consumption interrelate while estimating the adaptable security methods. Nisa et al.14propose a new method named TwophaseVerification for Attack Recognition, which aims to improve SDN security by mitigating DoS attacks. The method also contains the execution of packet filtration and ML classifier methods that are consequently monitored by the pursued limit of malicious network traffic. Rather than entirely disabling the host, the prominence reclines on averting dangerous communication. SVM and K-NN methods are used for effectual recognition on the CICDoS 2017 dataset. The method has been used in an atmosphere intended for threat recognition in SDN. Kavitha and Ramalakshmi15 propose an effectual DDoS attack recognition and inhibition methodology utilizing ML methods. The study analyses the SDN’s performance in IoT networks, integrating a massive group of computation devices which utilize multi-controllers.

Musa et al.16 proposed tackling the intrinsic security susceptibilities of SDN atmospheres and emerging automatic methods for identifying and mitigating system attacks. Traditional network measuring methods have been restricted in the context of SDNs, and the goal of the presented DL and ML methods is to overcome these restrictions by offering more precise and effective mitigation and detection of DDoS attacks. This study aims to provide a complete analysis of associated studies in SDN anomaly detection current developments, classified into dual classes by DLand ML techniques. Aslam et al.17 present an AMLSDM method. The presented AMLSDM method advances an SDN-enabled security mechanism for IoT devices with the help of an adaptable ML classifier method to attain the effective mitigation and recognition of DDoS attacks. The proposed structure uses ML techniques in an adaptable multi-layered feed-forwarding system to effectively recognize DDoS attacks by inspecting the static features of the studied network traffic. Ahmim et al.18 presented method goals to identify all DDoS attacks with their particular subgroup. This hybrid method integrates the various categories of DL methods, containing CNNs, LSTM, Deep AE, and DNNs. The presented method is composed of dual vital levels. The initial one comprises various equivalent sub-NN trained with particular methods. The next level utilizes the unmoving initial output integrated with the first data as input. Al Hwaitat and Fakhouri et al.19propose a novel Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) trainer that utilizes evolutionary computation methods. Benlloch-Caballero, Wang, and Calero20 present a new cognitive closed-loop system to present distributed dual-layer self-protection capabilities to battle against DDoS attacks. Huang et al.21propose BDE-IDS, a bidirectional differential evolution-based system for unknown cyberattack detection. This work presents an intelligent Game Theory-based Adaptive Security (GT-AS) model to enhance DDoS attack mitigation. Sureshkumar, Venkatesan, and Santhosh22 introduce a technique by using Density Peak Clustering Algorithms (DPCAs) to partition training sets for size and imbalance reduction.

Anoop et al.23present an Optimized Graph Transformer with a Molecule Attention Network (OGTMAN), which incorporates Secure Multi-party Computation (SMC) and differential privacy for enhanced security. The model utilizes min-max normalization, N-Tuple Contrastive Learning for feature extraction, and optimized feature selection using chi-square statistics. Al-Dunainawi, Al-Kaseem, and Al-Raweshidy24introduce an optimized model by using Mininet, Ryu controller, and a 1D-Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) to detect and reduce DDoS attacks in SDN environments. Hekmati and Krishnamachari25 introduce a robust solution by utilizing the capabilities of GCN. The study also presents a detection mechanism capable of operating efficiently even in lossy network environments. Various graph topologies are introduced for modelling IoT networks and evaluating them to detect tunable futuristic DDoS attacks. Ali et al.26 present a reactive recovery strategy for link failures using a TOPSIS module in an SDN controller to choose alternative paths based on multiple criteria. A DDoS detection and mitigation mechanism are also presented by employing blockchain (BC) and ML in SD-IoT. Rizvi et al.27propose an innovative and highly efficient approach that integrates diverse classification models comprising Random Forest (RF), Decision Tree (DT), Gradient Boosting, Linear SVM, Logistics, K-nearest neighbours (KNN), and AdaBoost for DDoS attack detection. Kostas, Just, and Lones28 present a model for IoT attack detection. This method uses isolated train and test datasets, evaluates various ML models, and applies explainable AI to identify key detection features. Sadhwani et al.29 present a scalable system that integrates ML and DL methods with optimized data processing to secure IoT devices against DDoS attacks. Aswad et al.30 propose integrating three deep DL methods, namely recurrent neural network (RNN), LSTM-RNN, and CNN, to build a bidirectional CNN-BiLSTM DDoS detection model. Pawar et al.31investigate attacks in IoT and SDN environments, exploring the incorporation of BC for enhanced security. The model also utilizes Attention-based Convolutional LSTM (At-C-L) to improve detection capabilities. Oladele and Jimoh32 analyze six DNN models, exhibiting that LSTM outperforms the other algorithms.

Ma et al.33 provide a comprehensive survey on DDoS defense solutions in Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) networks, exploring security threats, attack types, and current defense strategies. Vincent et al.34 proposes a GCN framework to detect FDI attacks by analyzing power network topology and fluctuating state estimations. Yang et al.35 propose STMIR, a secure and traceable multikey image retrieval system utilizing privacy-preserving Mahalanobis distance comparison, CNN-based feature extraction, and encrypted watermarking for secure retrieval and user tracking. Feng et al.36 introduces a learning-based DDoS detection approach using an enhanced k-nearest neighbors (KNN) approach with a k-dimensional (KD)-tree for faster detection and fine-grained classification of DDoS sources by IP risk level. Chen et al.37 propose an efficient and secure content-based image retrieval scheme for Cloud-assisted IoT, utilizing lattice-based homomorphic encryption, CKKS batch processing, and Private Information Retrieval to improve privacy and reduce computational overhead, with proven security and efficiency. Lo et al.38 proposes XG-BoT, an explainable deep GNN for botnet node detection. It also utilizes a reversible residual connection and graph isomorphism network for accurate detection and includes an explainer for automatic forensics, highlighting suspicious network flows and botnet nodes. Ma et al.39 presents a DDoS defense using a Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) for accurate attack detection and dynamic whitelist-based reduction with fast traffic rerouting to ensure service continuity. Li et al.40 presents AT-GCN, a DDoS attack path tracing system using a knowledge base and GCN, with a Tracing-Sample algorithm and dynamic traceability algorithm recommendations based on user needs. Qian et al.41proposes a distributed botnet detection methodology by using graph partitioning and GCNs, with METIS for efficient traffic division and diagonal enhancement to ensure accurate detection. Jemal, Cheikhrouhou, and Haddar42 improves IoT security by using CNNs to detect and counter DDoS and DoS attacks. Abinesh et al.43 introduces a Deep GCNN for effectually botnet detection, particularly for Mirai and Bashlite attacks, which are similar to DDoS attacks.

Lee and Han44propose a causal attention graph convolutional network (CAGCN) that utilizes node and neighbor attention to reduce bias from attacks, ensuring robust performance even under stronger attacks. Sanap and Aher45 proposes a DCNN-based SVMAK for DDoS detection and mitigation, utilizing WSMOTE to address data imbalance and HGSO for feature selection. Khalid Alkahtani et al.46 presents an Optimal GCNN based Ransomware Detection (OGCNN-RWD) technique for IoT environments, using learning enthusiasm for teaching learning-based optimization (LETLBO) for feature selection and the GCNN model with hyperparameters optimized by harmony search algorithm (HSA). Saunders et al.47 presents the design of a GCN-based DDoS detection system. Kisanga et al.48 introduces an Activity and Event Network (AEN)-based supervised Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) model. Altaf et al.49introduces a GGCN framework for botnet detection in IoT networks, employing time-stamped multi-edge graphs and a gated graph model to capture temporal patterns in network traffic. Alhayani and Murphy50presents an efficient ML-based DDoS detection approach by employing chi-square for feature selection to ensure efficiency with minimal input features. Thota, Prathibhavani, and Venugopal51 present a new hybrid approach, called GNN-WGAN, to efficiently detect bots in IoT-based smart city networks by integrating Graph Neural Network (GNN) and Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network (WGAN). Barsellotti et al.52 introduces a two-level hierarchical graph representation and GNN method to integrate traffic- and flow-level relationships, maximizing information from the traffic structure without needing stateful features.

The existing studies for mitigating and detecting DDoS attacks portray diverse limitations. One model employs an FPGA-based platform, which may deter scalability and adaptability across several IoT environments, concentrating primarily on DoS attacks while neglecting other potential threats. A hybrid model incorporating CNNs and LSTMs may be computationally intensive, impacting real-time detection capabilities. Moreover, reliance on a limited set of parameters might oversimplify mitigation strategies, and specific methods could face difficulty with high volumes of malevolent traffic, resulting in false negatives. The complexity of some hybrid models may result in longer training times and extensive resource requirements. Additionally, conventional measurement methods may only effectually address some security vulnerabilities in dynamic conditions, and the efficiency of specific models could diminish when faced with growing DDoS attack strategies. Lastly, while some approaches underscore multi-criteria decision-making, they risk oversimplifying intrinsic scenarios, potentially resulting in suboptimal outcomes. Despite enhancements in DDoS attack detection and mitigation, crucial research gaps remain in the adaptability and scalability of these methods across various IoT environments. Many existing approaches concentrate on specific attack vectors or depend on limited parameters, which can oversimplify complex threat landscapes. Additionally, there is a need for more robust models that effectually balance computational efficiency with high detection accuracy in real-time scenarios. Enhanced integration of explainable AI techniques could also improve trust and transparency in detection mechanisms.

Proposed Method

This manuscript proposes the SSODE-GCNDM methodology in the IoT environment. The main intention of the SSODE-GCNDM method is to recognize the presence of DDoS attack behaviour in IoT platforms. It encompasses four phases: data normalization, feature selection, classification, and parameter tuning, as demonstrated in Fig. 2.

Phase I: Z-score normalization

Primarily, the SSODE-GCNDM technique involves Z-score normalization to scale the input data into a uniform format53. The Z-score normalization is a powerful technique for standardizing data, as it converts features to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation (SD) of one. This method is specifically beneficial when dealing with datasets that exhibit varying scales, confirming that all features contribute equally to the model’s performance. By reducing the influence of outliers, Z-score normalization improves optimization algorithms’ stability and convergence speed. Compared to other normalization methods, namely min-max scaling, Z-score normalization is less sensitive to extreme values, making it a more robust choice in various applications. Its capability to facilitate better interpretability of results also assists in more precise insights during model evaluation. Overall, its efficiency in preparing data for complex models makes it an excellent choice in scenarios needing precision and reliability.

Z-score normalization is an arithmetical model employed to regulate data by converting it into a mutual scale, usually with a mean of 0 and an SD of 1. Z-score normalization aids in equating and examining network traffic patterns by removing the effects of opposing units and scales. This procedure includes deducting the mean of the data and isolating it by its SD, permitting a more uniform depiction of traffic features. Using Z-score normalization, anomalous behaviour indicative of DDoS attacks is more easily identified as deviations from the norm. This technique enhances the effectiveness of anomaly detection algorithms by providing a consistent basis for comparison across diverse IoT devices and network conditions. Consequently, it aids in improving the overall accuracy and efficiency of DDoS recognition and mitigation strategies.

Phase II: feature selection

For the feature selection process, the presented SSODE-GCNDM technique utilizes the SSO-DE approach54. This method presents a unique merit by integrating the strengths of both optimization models. The SSO model effectually explores the solution space through collaborative swarm intelligence, endorsing diversity and adaptability, while Differential Evolution (DE) improves convergence speed and robustness in finding optimal feature subsets. This hybrid approach is specifically useful for high-dimensional datasets, where conventional techniques may need to assist computational efficiency and overfitting difficulty. Compared to other feature selection methods, SSO-DE balances exploration and exploitation, resulting in more relevant and compact feature sets. Its capacity to dynamically adjust to the data landscape confirms a more tailored feature selection process, ultimately enhancing the model’s performance. This synergy enhances predictive accuracy and simplifies model interpretation and implementation. Figure 3 illustrates the structure of the SSO-DE model.

Natural swarms’ synergistic and cooperative behaviour stimulates the advanced optimization approach SSOA. This model utilizes an agent swarm that collaborates to solve complex issues successfully. The key process of the suggested SSOA approach is presented below. The optimization process begins with selecting candidate solutions in Eq. (1).

Equation (1) makes a matrix \(\:X\) of size \(\:\left(NxDim\right)\) with randomly generated values inside known ranges. The framework of these matrices is assumed in Eq. (2)

whereas \(\:N\) characterizes solutions or particles, \(\:Dim\) symbolizes variables or dimensions of the known problem, \(\:and\:UB\) and \(\:LB\) represent upper and lower limit vectors for every problem space dimension.

The candidate solutions (X) are upgraded using the Eq. (3).

Now, \(\:Xnew(i,\:j)\) signifies the original optimization position \(\:j\) of the \(\:ith\) candidate solution, \(\:X\left(i,\:j\right)\) stands for present position \(\:j\) of the \(\:ith\) candidate solution, \(\:v\left(i,\:j\right)\) characterizes the position \(\:j\) of the \(\:ith\) value of the candidate solution.

Additionally, the velocity updated equation introduces a dynamic attraction equation that impacts the particles’ movement near more favourable areas of the search space. These equations are calculated to adaptably guide the particles depending on the global and local attraction of the positions.

The subsequent equations design the vnew(i, j) values. The inertia weight value (IWV) is computed in the following:

Here, \(\:w\) represents an adaptable method for controlling the balance between dynamical exploitation and exploration using the inertia weight parameter (w).

The adaptable neighbourhood communication equation encourages a concentrated search space exploration by providing more weight to particles with greater fitness, permitting the swarm to meet more powerfully. Present an equation that dynamically adjusts the interaction power between particles depending on their fitness values. This equation allows particles with superior fitness to have a robust inspiration for the movement of their neighbours. The inertia weight is upgraded at every iteration via an adaptable equation:

Now, \(\:k\) denotes the constant that regulates the decline in the inertia weight rate, and \(\:t\) symbolizes the present iteration. This model slowly moves from exploration to exploitation by decreasing the inertia weight on time, encouraging convergence, and fine-tuning near the optimum solution. The personal best coefficient (PBC) is computed in the following:

Here, \(\:r1\) represents a value of random, \(\:eps\) provides a smaller value, \(\:rand\left(pbest\right)\) denotes a random solution from the present candidate solutions, and \(\:{X}_{i}\) offerings the \(\:i\:th\) solution number. The global best coefficient (GBC) is computed in the following:

Whereas \(\:r2\) denotes random value, \(\:gbes{t}_{t}\) signifies the globally best solution (at several iterations \(\:t\)), and \(\:{X}_{i}\) gives the number of solutions. Consists of a diverse conservation equation that inspires the exploration of varied areas inside the search space. The dynamic attraction coefficient (DAC) is computed in the following:

Here, \(\:r3\) represents randomized value, \(\:attrac{t}_{i}\) characterizes the position with the greater local attraction value inside the neighbourhood of the particle\(\:\:i\), \(\:cl\) denotes the added acceleration coefficient for the dynamically attracted word, and \(\:{X}_{i}\) provides the number of solutions \(\:i\). The dynamically attracted word leader’s particles near high attracted positions, endorsing fast convergence near optimum solutions. The adaptive neighbourhood interaction coefficient (ANIC) is computed in the following:

Now, \(\:r4\) signifies a randomly generated value, \(\:rand\left(bestf\right)\) denotes a randomly selected fitness value from the present fitness solutions, and \(\:best{f}_{i}\) represents the fitness value of the \(\:ith\) solution. The diversity maintenance coefficient (DMC) is measured as below:

Whereas \(\:r5\) stands for randomly formed value, \(\:c2\) is an added accelerated coefficient for the term of diversity. \(\:diversit{y}_{i}\) characterizes a position inside the swarm that increases the diversity during the \(\:ith\) particle neighbourhood.

DE Model.

The DE model presented by Storn and Price is an efficient and robust search model intended to challenge complicated, constant, non-linear functions55. The Conventional DE (method begins by initializing a population of \(\:N\) individuals signified as vector \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}_{i}\), whereas \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}_{\text{i}}=\left({X}_{i1},{X}_{i2},\:{X}_{i3},\:\dots\:,{X}_{in}\right),i=\text{1,2},3,\dots\:,N\), and \(\:n\) represent the dimension of the problem. The DEA technique has integrated three main operators: crossover, selection, and mutation. The mutation and crossover operators are used to give new candidate vectors. Simultaneously, a selection approach has been applied to control the survival of both the parent and the offspring in the following generation.

Stage of mutation

An individual with genetic mutations has been characterized based on Eq. (12) whereas \(\:{\overrightarrow{V}}_{\text{i}}=\left({v}_{i1},\:{v}_{i2},\:{v}_{i3},\:{v}_{in}\right)\) and is made using a mutation operator. Numerous mutation models are recognized in this work. A unique often applied operator is ‘DE/best/1’, which is described as:

Where \(\:t\) characterizes the present iteration, \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}^{\text{*}}\left(t\right)\) symbolizes the finest individual with the lower \(\:f{\left(\overrightarrow{X}\right)}^{*}\). Now, \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are two indices selected at random between the range \(\:[\)1, \(\:N]\), whereas \(\:a,\)\(\:b\), and \(\:i\) are all distinct from one another \(\:\alpha\:\ne\:\beta\:\ne\:i\in\:1\dots\:,N\)). In addition, \(\:F\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\) characterizes a mutation scaling factor manipulating the discrepancy variation among two individuals.

Stage of crossover

The crossover parameter has been applied to every mutation individual, and it is related to a targeted individual \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}_{i}\) to offer an experimental vector, \(\:{\overrightarrow{U}}_{\text{i}}=({u}_{i1},{u}_{i2},{u}_{i3},\dots\:,\:{u}_{i,n})\). Binomial and exponential crossovers are regularly used crossover tactics. The binomial crossover has been stated based on Eq. (13):

The index \(\:R\) symbolizes a dimensionally selected random number from the set \(\:1,\:2,\dots\:,n\). This is completed to promise that at the smallest one dimension from \(\:{\overrightarrow{V}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{t}\right)\), current is current in the individual \(\:{\overrightarrow{U}}_{i}\), which varies from its targeted vector, \(\:{\overrightarrow{V}}_{i}\). The crossover rate \(\:\left(CR\right)\) represents the value ranging between \(\:0\) and 1, and \(\:{r}_{j}\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\) stands for a randomly formed number distributed uniformly among \(\:0\) and 1.

Stage of selection

A one-to-one greedier selection has been applied in DE to regulate when the experimental individual \(\:{\overrightarrow{U}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) will be incorporated into the targeted population for the following generation. The one-to‐one selection approach controls by defining the survival of the more suitable person among the experimental individual \(\:{\overrightarrow{U}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{t}\right)\) and its targeted counterpart \(\:{\overrightarrow{X}}_{i}\). The expression for minimization problems has been based on Eq. (14):

Here, \(\:f\) denotes the function of the objective. The process mentioned above is iterated till an end requirement is attained.

The SSOA integration with DE influences the balancing powers of both models to improve optimization performance. SSO outshines exploring the searching space using the cooperative interaction and behaviour of swarm agents, which allows efficient exploration of different areas. DE, alternatively, concentrates on developing these areas over crossover operations and differential mutation. SSO is initially applied to recognize and encourage search space regions during this hybrid model. After identifying this region, DE has been used to fine-tune the solutions. This grouping increases the exploration or exploitation stages, leading to a more effectual searching method and improved optimizer outcomes. The incorporation is mathematically defined in the following:

Updating the position of all agents in the swarm using:

Here, \(\:{x}_{i}\left(t\right)\) represents the position of the \(\:i-th\) agent at time \(\:t,\)\(\:{x}_{best}\left(t\right)\) denotes the best position founded by the swarm, \(\:{x}_{j}\left(t\right)\) and \(\:{x}_{k}\left(t\right)\) are positions of agents selected at random, and \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are coefficients adjusting the impact of the best agent and the changes among other agents.

Afterwards, exploration of SSO, use DE for local refinement:

Here, \(\:{v}_{i}\) represents the mutant vector for the \(\:i-th\) individual, \(\:{x}_{r}1\), \(\:{x}_{r}2\), \(\:{and\:x}_{r}3\) are individuals selected randomly from the population, and \(\:F\) represents a scaling factor. Create the experimental vector \(\:{u}_{i}\) using crossover and choose the best individuals for the following generation. These hybrid models associate the wide-ranging searching abilities of SSO with the accurate optimization algorithms of DE, resulting in an efficient and robust technique for composite optimizer difficulties.

In the SSO-DE method, the objectives are combined into a solitary objective formula such that a current weight classifies every objective’s importance. In this study, a fitness function (FF) that incorporates both objectives of FS is utilized and shown in Eq. (17).

Whereas Fitness(X) signifies the fitness rate of subset \(\:X,\)\(\:E\left(X\right)\) denotes the classification rate of error by utilizing the chosen features within the X subset. \(\:\left|R\right|\) and \(\:\left|N\right|\) are the counts of selected features and novel features within the dataset. Correspondingly, \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are the weights of the classification error and the decrease ratio, \(\:\alpha\:\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\) and \(\:\beta\:=(1-\alpha\:)\).

Phase III: attack detection using GCN technique

Moreover, the GCN technique recognizes and mitigates DDoS attacks56. This model for attack detection utilizes the ability to model complex relationships and dependencies in data, which is particularly advantageous in network security contexts. GCNs capture the structural data inherent in graph-structured data, allowing them to detect patterns and anomalies that may indicate potential attacks. Unlike conventional techniques that treat features independently, GCNs integrate the interconnections between data points, giving a richer understanding of the overall system. This capability enhances detection rates, mainly in scenarios with intricate attack patterns. Moreover, GCNs are adaptable to varying data types and can scale well with increasing data complexity. Their performance extracting meaningful insights from relational data makes GCNs a superior option for enhancing security measures in dynamic environments. Figure 4 depicts the architecture of the GCN model.

During these studies, layers of GCN were selected according to the graphical convolution operator. The operator was presented to extract features from molecular fingerprints. GCNs are notorious for their capacity to make node embeddings that take necessary structural information from the graph. This is mainly helpful in tasks requiring understanding objects’ connections and relationships. GCNs use a convolution process similar to traditional CNNs to combine information from adjacent nodes but also slot in distanced information of the local area. The sharing of parameters enables the GCN scalability, for the parameters are shared uniformly through each node. The operator of GCN follows the layer-to-layer rule of propagation that is described as:

Here, \(\:{H}^{\left(l\right)}\) signifies the input graph by\(\:\:l\:th\) layer, and \(\:{H}^{(l+1)}\) symbolizes the output by \(\:the\:l+1\:\text{t}\text{h}\:\)layer. The matrix \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{A}=A+{I}_{N}\) is the adjacent matrix with additional self-loops to every node. The matrix \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{D}\) signifies a diagonal matrix delineated as \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{D}}_{\text{i}\text{i}}={\varSigma\:}_{j}\left(\stackrel{\sim}{A}\right)\). The training matrix precise to the layer is denoted as \(\:{W}^{\left(l\right)}\), and \(\:\sigma\:\) symbolizes the activation function implementation. Equation (18) is inspired by an initial‐order estimate of training local spectral filters \(\:{g}_{\theta\:}\) on graphs. A spectral convolution (meant as \(\:\text{*}\)) from the input graph \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{x}\) using a filter \(\:{g}_{\theta\:}\) parametrized by \(\:\theta\:\) within the Fourier domain is specified as:

Now, \(\:U\) symbolizes the eigenvectors matrix, with its eigenvalues signified as \(\:\varLambda\:\), gained from \(\:L={I}_{N}-{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}A{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}=U\varLambda\:U\), whereas \(\:{D}_{ii}={\sum\:}_{j}(A)\) denotes the diagonal matrix. By stating \(\:{g}_{\theta\:}\) for \(\:\varLambda\:\) function and estimating it over Chebyshev polynomials truncation equal to the \(\:{K}^{th}\) order, the \(\:L\) eigendecomposition is calculated, resulting in:

Here, \(\:{\theta\:}^{{\prime\:}}\) denotes the Chebyshev coefficients vector, and \(\:{T}_{k}\left(\stackrel{\sim}{L}\right)\) represents \(\:{the\:k}^{th}\) Chebyshev polynomial utilized to \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{L}=\frac{2}{{\lambda\:}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}}L-{I}_{N}\) with \(\:{\lambda\:}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\) indicating the maximal matrix eigenvalue \(\:\varLambda\:.\)

Decreasing the parameter counts helps address streamlining and overfitting operations in each layer. By limiting the order of Chebyshev to \(\:K=1\) and estimating the \(\:{\lambda\:}_{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\:\)value to 2 (assuming that neural network parameters regulate these scale changes in training), Eq. (20) facilitates:

Continual implementation of these operators can lead to numerical variabilities, producing both vanishing gradients and exploding, mainly in connection with DNN techniques. Renormalization habits have been suggested to address these problems. Over continuous pooling operation applications, information from a node is transmitted over progressively different areas. For example, with \(\:{k}_{l}\) concatenation layers of GCN, inspiration is extended to the \(\:{k}_{l}^{th}\)-order area near node \(\:i.\) Finally, the GCN layer output is served over an activation function \(\:\sigma\:\) to present non-linearity. Hence, the operation at every layer \(\:l\) contains the operator of GCN in Eq. (18) using the PReLU operator applied by the activation function:

Phase IV: NGO-based parameter tuning

Finally, the presented SSODE-GCNDM model implements the NGO method to fine-tune the hyperparameters involved in the GCN method57. This method is an efficient parameter-tuning technique motivated by goshawks’ hunting behaviours, enabling it to explore the solution space effectively. Its adaptive search mechanism is specifically beneficial for optimizing hyperparameters in complex models, resulting in improved performance and accuracy. The capability of the NGO model to balance exploration and exploitation assists in preventing premature convergence, a general problem in conventional optimization methods. Compared to other techniques, namely grid or random search, NGO presents a more systematic and intelligent approach, often needing fewer evaluations to attain optimal settings. This efficiency not only saves computational resources but also accelerates the tuning process. Moreover, NGOs can be easily integrated with diverse ML models, making it a versatile choice for diverse applications in model optimization. Its efficiency in attaining high-quality solutions distinguishes it from conventional tuning methods. Figure 5 demonstrates the structure of the NGO model.

Stimulated by the predatory behaviour of the northern goshawk, the NGO captures every northern goshawk as an individual of a population and extracts the predatory behaviour into 2 phases. The initial phase is to attack and explore prey that replicates the group behaviour by recognizing the location of the present best solution and inducing every individual to update their position over the optimal solution, demonstrating the global exploration abilities. The next phase represents the escaping behaviour of prey, implying the local exploitation abilities.

Initialization.

NGO believes every northern goshawk is an individual of a population that is a possible solution, searching for the finest value in the potential solution space by transferring. Similarly, in swarm intelligence algorithms (SIA), NGO makes initial populations by randomly generating earlier populations. During the mathematical approach, every individual symbolizes a D-dimensional vector, N individuals establish the complete population, and the population is an \(\:N\times\:D\) matrix. The population’s mathematical technique is depicted in the following equation.

Now, the population \(\:N\) and the individual’s position are characterized by \(\:X\) and \(\:{X}_{i}\). Individually, \(\:{X}_{i\:and\:j}\) represent the value of the \(\:{j}_{th}\) dimension, and \(\:M\) denotes individual counts and the larger dimension. The FF signifies the objective function.

Attack and Identification of Prey.

The prey attack and search is the primary phase of the NGO in every iteration, which pretends the optimal solution as prey and every individual presents the attack. During these phases, each individual recognizes the position of the present best solution and upgrades their position depending on these optimum solutions. The leading resolution is to allow the northern goshawk individual to more commonly hunt the possible solution space. Hence, a global search has been performed. Eqs. \(\:\left(24\right)-\left(26\right)\) characterize the mathematical representation for the first stage.

Here, \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,\)\(\:N\), \(\:I\) value is 1 or 2, and \(\:r=rand\) (\(\:\text{0,1}).{P}_{i}\) denotes the candidate solution. \(\:{F}_{{P}_{i}}\) represents the value of an objective function. \(\:{x}_{i}^{new1}\) symbolizes the new position of the initial phase and \(\:{x}_{i,j}^{new1}\) is its \(\:{j}_{th}\) dimension. \(\:{F}_{i}^{new1}\) characterizes the value of the objective function of the initial phase.

Operation of Escape and Chase.

The 2nd phase represents escaping and chasing prey, and the local exploitation is performed by mimicking the local actions of prey to affect the individual position of the northern goshawk. The position updating equation of the 2nd phase has been exposed in Eqs. \(\:\left(27\right)-\left(28\right)\):

Now, \(\:{x}_{i}^{new2}\) stands for an original position in the 2nd phase and \(\:{x}_{i.j}^{new2}\) represents its value in \(\:{the\:j}_{th}\) dimension. \(\:{F}_{i}^{new2}\) characterizes the value of the objective function of 2nd phase. \(\:R\) denotes the searching radius. The \(\:R\) expression is shown below

whereas \(\:t\) signifies the number of iterations, \(\:T\) indicates the maximum number. \(\:R\) should reduce as the number of iterations upsurges, demonstrating that the searching radius of the NGO bonds in the advanced iteration phases, thus improving the model’s local exploitation proficiency. These methods have been essential to NGOs’ achieving better optimization accuracy than others. Every iteration of the NGO process includes these two stages. Upon accomplishment of the maximal iteration boundary, the algorithm ends.

Fitness selection is a substantial feature that induces the performance of the NGO method. The hyperparameter choice process includes the encoding methodology to assess the efficiency of the candidate results. In this study, the NGO method studies precision as the primary criterion for designing the FF.

\(\:TP\) implies the true positive, and \(\:FP\) signifies the false positive value.

Performance validation

The simulation validation of the SSODE-GCNDM technique is studied utilizing the dataset58. The dataset contains 1600 samples under dual-class labels, as represented in Table 1. The ten features are Represents the total duration of the captured packets (tot_dur), Placeholder for nanoseconds part of the duration (dur_nse), Time difference between consecutive packets (dt), Duration between consecutive packets (dur), received kilobits per second (rx_kbps), Determines the packet protocol (Protocol), Transmitted kilobits per second (tx_kbps), Rate of packet arrival per second (pktrate), Total kilobits per second (tot_kbps), and Port number (port_no). But, only six features are selected: Time difference between consecutive packets (dt), Rate of packet arrival per second (pktrae), Total kilobits per second (tot_kbps), Duration between consecutive packets (dur), Transmitted kilobits per second (tx_kbps), and received kilobits per second (rx_kbps).

The suggested technique is simulated using the Python 3.6.5 tool on a PC with an i5-8600k, 250GB SSD, GeForce 1050Ti 4GB, 16GB RAM, and 1 TB HDD. The parameter settings are learning rate: 0.01, activation: ReLU, epoch count 50, dropout: 0.5, and batch size: 5.

Figure 6 reports a set of confusion matrices produced by the SSODE-GCNDM method on different epochs. On 500 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM model has identified 991 samples as DDoS attacks and 579 samples as normal. In addition, on 1000 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM method has identified 999 samples as DDoS attacks and 596 samples as normal. Followed by, on 1500 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM model has identified 994 samples into DDoS attack and 587 samples as normal. Finally, on 2500 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM technique has approached 994 samples into DDoS attack and 591 samples into normal.

The DDoS recognition outcomes of the SSODE-GCNDM method are determined under distinct epochs in Table 2; Fig. 7. The table values state that the SSODE-GCNDM method correctly recognized DDoS attacks and normal samples. On 500 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM method provides an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 97.80%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.20%, \(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 97.80%, \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 97.99%, and \(\:{G}_{Means}\) of 98.00%. Likewise, on 1000 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM methodology offers an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.62%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 99.72%, \(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 99.62%, \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 99.67%, and \(\:{G}_{Means}\) of 99.67%. Moreover, on 1500 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM methodology gains an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.62%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.85%, \(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 98.62%, \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 98.73%, and \(\:{G}_{Means}\) of 98.73%. Finally, on 3000 epochs, the SSODE-GCNDM methodology provides an average \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 98.05%, \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 98.35%, \(\:rec{a}_{l}\) of 98.05%, \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 98.19%, and \(\:{G}_{Means}\) of 98.20%.

In Fig. 8, the training (TRA) and validation (VLA) accuracy outcomes of the SSODE-GCNDM approach under epoch 1000 are displayed. The accuracy values are computed for 0–1000 epochs. The figure highlighted that the TRA and VLA accuracy values display a rising tendency, which indicates the ability of the SSODE-GCNDM model to improve performance over several iterations. Also, the TRA and VLA accuracy remains closer over the epochs, showing low minimal overfitting and enhanced performance of the SSODE-GCNDM model, guaranteeing consistent prediction on unseen samples.

Figure 9 displays the TRA and VLA loss graph of the SSODE-GCNDM model at epoch 1000. The loss rates are computed for 0–1000 epochs. It is signified that the TRA and VLA accuracy rates display a lower trend, notifying the ability of the SSODE-GCNDM method to balance a trade-off between data fitting and generalization. The continual reduction in loss values guarantees the enhanced performance of the SSODE-GCNDM methodology and tunes the prediction results over time.

In Fig. 10, the precision-recall (PR) curve analysis of the SSODE-GCNDM approach under epoch 1000 interprets its performance by plotting Precision against Recall for all the classes. The figure shows that the SSODE-GCNDM approach continuously accomplishes improved PR values across different class labels, representing its capability to maintain a significant portion of true positive predictions amongst each positive prediction (precision) while capturing a large proportion of actual positives (recall). The steady rise in PR results among all classes depicts the effectiveness of the SSODE-GCNDM technique in the classification process.

In Fig. 11, the ROC curve of the SSODE-GCNDM model is studied. The outcomes imply that the SSODE-GCNDM model reaches enhanced ROC outcomes over each class under epoch 1000, representing a significant ability to discriminate the classes. This reliable tendency of improved ROC values over various classes indicates the efficient performance of the SSODE-GCNDM approach in predicting classes, emphasizing the robust nature of the classification process.

The comparative analysis of the SSODE-GCNDM methodology with existing approaches is illustrated in Table 3; Fig. 1259,60,61,62,63. The simulation result indicated that the SSODE-GCNDM approach outperformed better performances. Regarding \(\:acc{u}_{y}\), the SSODE-GCNDM approach has a better \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 99.62%. In contrast, the Logistic Regression (LR), KNN, RF, DT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and DNN, Quantum CNN (QCNN), global search strategy of the coyote optimization algorithm with Improved deep neural network (COA-GS-IDNN), Grey Wolf Optimizer and Long Short-Term Memory (GWO-LSTM), and Autoencoder (AE) methods have the lowest \(\:acc{u}_{y}\) of 91.10%, 97.00%, 98.54%, 98.36%, 98.09%, 98.34%, 98.98%, 99.37%, 99.25%, 98.71%, 99.10%, and 98.95%, correspondingly. Likewise, for \(\:pre{c}_{n}\), the SSODE-GCNDM method has a high \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 99.72%, while the LR, KNN, RF, DT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, MLP, DNN, QCNN, COA-GS-IDNN, GWO-LSTM, and AE methodologies have minimal \(\:pre{c}_{n}\) of 91.00%, 97.00%, 98.52%, 98.64%, 98.08%, 98.65%, 98.67%, 99.17%, 99.12%, 99.41%, 98.87%, and 98.82%, respectively. Finally, based on \(\:{F}_{measure}\), the SSODE-GCNDM method has superior \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 99.67% while the LR, KNN, RF, DT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, MLP, DNN, QCNN, COA-GS-IDNN, GWO-LSTM, and AE techniques exhibited the lowest \(\:{F}_{measure}\) of 91.00%, 97.00%, 98.79%, 97.82%, 98.35%, 98.46%, 98.61%, 98.82%, 98.59%, 98.70%, 98.82%, and 98.82%, respectively.

In Table 4; Fig. 13, the comparative results of the SSODE-GCNDM approach are specified in terms of computational time (CT). The outcomes suggest that the SSODE-GCNDM approach gets better performance. Based on CT, the SSODE-GCNDM approach offers a reduced CT of 05.92s whereas the LR, KNN, RF, DT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, MLP, DNN, QCNN, COA-GS-IDNN, GWO-LSTM, and AE models attain better CT values of 11.68s, 10.61s, 14.17s, 09.91s, 07.42s, 11.96s, 11.14s, 12.45s, 10.07s, 09.12s, 13.11s, and 12.20s, correspondingly.

Conclusion

This manuscript proposes the SSODE-GCNDM technique in the IoT environment. The main intention of the SSODE-GCNDM method is to recognize the presence of DDoS attack behaviour in IoT platforms. Primarily, the SSODE-GCNDM technique involves Z-score normalization to scale the input data into a uniform format. The presented SSODE-GCNDM technique utilizes the SSO-DE method for the feature selection process. Moreover, the GCN technique is employed to recognize and mitigate attacks. Finally, the presented SSODE-GCNDM model implements the NGO method to fine-tune the parameters involved in the GCN method. A wide range of experimentation analyses occur, and the outcomes are observed in numerous aspects. The experimental validation of the SSODE-GCNDM technique portrayed a superior accuracy value of 99.62% compared to existing approaches. The presented SSODE-GCNDM approach has limitations, such as sensitivity to data quality and potential overfitting when working with high-dimensional datasets. The reliance on specific optimization algorithms may also restrict adaptability to diverse problem domains. Future work should focus on enhancing model robustness through enhanced data preprocessing and combining ensemble techniques to reduce overfitting. Furthermore, exploring unsupervised learning methods could give valuable insights when labelled data is scarce. Examining the transfer learning (TL) model application may improve performance across varying contexts. Expanding the framework to accommodate real-time attack detection could enhance practical applicability in dynamic environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

11 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92451-5

References

Karmous, N., Aoueileyine, M. O. E., Abdelkader, M., Romdhani, L. & Youssef, N. Software-Defined-Networking-Based One-versus-Rest Strategy for Detecting and Mitigating Distributed Denial-of-Service Attacks in Smart Home Internet of Things Devices. Sensors, 24(15), p.5022. (2024).

Ramprasath, J., Krishnaraj, N. & Seethalakshmi, V. Mitigation services on SDN for distributed denial of service and denial of service attacks using machine learning techniques. IETE J. Res. 70 (1), 70–81 (2024).

Arachchige, K. G., Branch, P. & But, J. An Analysis of Blockchain-Based IoT Sensor Network Distributed Denial of Service Attacks. Sensors, 24(10), p.3083. (2024).

Kumar, G. & Pragya IPv6 addressing with hidden duplicate address detection to mitigate denial of service attacks in the internet of drone. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, p.e8131. (2024).

Hnamte, V., Najar, A. A., Nhung-Nguyen, H., Hussain, J. & Sugali, M. N. DDoS attack detection and mitigation using deep neural network in SDN environment. Computers & Security, 138, p.103661. (2024).

Zaki, A. M., Abdelhamid, A. A., Ibrahim, A., Eid, M. M. & El-Kenawy, E. S. M. Enhancing K-Nearest neighbors Algorithm in Wireless Sensor networks through Stochastic Fractal Search and particle swarm optimization. J. Cybersecur. Inform. Manage., 13(1). (2024).

Varma, A., Kumar, A. T. & Yamini, B. April. Detection and Prevention of Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Attacks Using Machine Learning Techniques. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Networking and Communications (ICNWC) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. (2024).

Kumar, A. & Singh, D. Detection and prevention of DDoS attacks on edge computing of IoT devices through reinforcement learning. Int. J. Inform. Technol. 16 (3), 1365–1376 (2024).

Shah, Z., Ullah, I., Li, H., Levula, A. & Khurshid, K. Blockchain based solutions to mitigate distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks in the Internet of Things (IoT): A survey. Sensors, 22(3), p.1094. (2022).

Ali, M. H. et al. Threat analysis and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack recognition in the internet of things (IoT). Electronics, 11(3), p.494. (2022).

Sanlı, M. Detection and mitigation of denial of service attacks in internet of things networks. Arab. J. Sci. Eng., pp.1–11. (2024).

Abid, Y. A., Wu, J., Xu, G., Fu, S. & Waqas, M. Multi-level Deep Neural Network for Distributed Denial-of-Service Attack Detection and classification in Software-defined networking supported internet of things networks. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Kumar, S. & kumar Keshri, A. An effective DDoS attack mitigation strategy for IoT using an optimization-based adaptive security model. Knowledge-Based Systems, 299, p.112052. (2024).

Nisa, N., Khan, A. S., Ahmad, Z. & Abdullah, J. Two-phase authentication system for denial of service attack detection and mitigation using machine learning in software‐defined network. Int. J. Network Manage. 34 (3), e2258 (2024).

Kavitha, D. & Ramalakshmi, R. Machine learning-based DDOS Attack Detection and Mitigation in SDNs for IoT environments. J. Franklin Inst., p.107197. (2024).

Musa, N. S., Mirza, N. M., Rafique, S. H., Abdallah, A. & Murugan, T. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for distributed denial of service anomaly detection in software defined networks-current research solutions. IEEE Access. (2024).

Aslam, M. et al. Adaptive machine learning based distributed denial-of-services attacks detection and mitigation system for SDN-enabled IoT. Sensors, 22(7), p.2697. (2022).

Ahmim, A., Maazouzi, F., Ahmim, M., Namane, S. & Dhaou, I. B. Distributed denial of service attack detection for the internet of things using hybrid deep learning model. IEEE Access. 11, 119862–119875 (2023).

Al Hwaitat, A. K. & Fakhouri, H. N. Adaptive Cybersecurity Neural Networks: An Evolutionary Approach for Enhanced Attack Detection and Classification. Applied Sciences, 14(19), p.9142. (2024).

Benlloch-Caballero, P., Wang, Q. & Calero, J. M. A. Distributed dual-layer autonomous closed loops for self-protection of 5G/6G IoT networks from distributed denial of service attacks. Computer Networks, 222, p.109526. (2023).

Huang, H., Li, T., Li, B., Wang, W. & Sun, Y. A bidirectional Differential Evolution based unknown Cyberattack Detection System. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. (2024).

Sureshkumar, S., Venkatesan, G. P. & Santhosh, R. Detection of DDoS attacks on Cloud Computing Environment using altered Convolutional Deep Belief Networks. Int. J. Comput. Netw. Inform. Secur. 15 (5), 63–72 (2023).

Anoop, M., Mary, L. W., Wilson, A. J. & Kiran, W. S. Optimized graph transformer with molecule attention network based multi class attack detection framework for enhancing privacy and security in WSN. Multimedia Tools and Applications, pp.1–32. (2024).

Al-Dunainawi, Y., Al-Kaseem, B. R. & Al-Raweshidy, H. S. Optimized artificial intelligence model for DDoS detection in SDN environment. IEEE Access. (2023).

Hekmati, A. & Krishnamachari, B. Graph-Based DDoS Attack Detection in IoT Systems with Lossy Network. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09118. (2024).

Ali, J., Shan, G., Gul, N. & Roh, B. H. An intelligent blockchain-based secure link failure recovery framework for software-defined internet-of-things. Journal of Grid Computing, 21(4), p.57. (2023).

Rizvi, F. et al. An evolutionary KNN model for DDoS assault detection using genetic algorithm based optimization. Multimedia Tools Appl., pp.1–24. (2024).

Kostas, K., Just, M. & Lones, M. A. IoTGeM: Generalizable Models for Behaviour-Based IoT Attack Detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01343. (2023).

Sadhwani, S., Mathur, A., Muthalagu, R. & Pawar, P. M. 5G-SIID: an intelligent hybrid DDoS intrusion detector for 5G IoT networks. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet., pp.1–21. (2024).

Aswad, F. M., Ahmed, A. M. S., Alhammadi, N. A. M., Khalaf, B. A. & Mostafa, S. A. Deep learning in distributed denial-of-service attacks detection method for Internet of Things networks. Journal of Intelligent Systems, 32(1), p.20220155. (2023).

Pawar, P. P., Kumar, D., Ananthan, B., Pradeepa, A. S. & Selvi, A. S. May. An efficient ddos attack detection using attention based hybrid model in blockchain based SDN-IOT. In 2024 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence For Internet of Things (AIIoT) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. (2024).

Oladele, T. O. & Jimoh, E. R. Analysis of deep neural networks algorithms for mitigating distributed denial of service attacks in Software defined networks. FUW Trends Sci. Technol. 8 (3), 353–360 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. A Survey of DDoS Attack and Defense technologies in Multi-access Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Vincent, E., Korki, M., Seyedmahmoudian, M., Stojcevski, A. & Mekhilef, S. Detection of false data injection attacks in cyber–physical systems using graph convolutional network. Electric Power Systems Research, 217, p.109118. (2023).

Yang, T. et al. Secure and traceable multikey image retrieval in cloud-assisted internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Feng, Y., Li, J., Sisodia, D. & Reiher, P. On Explainable and Adaptable Detection of Distributed Denial-of-Service Traffic. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing. (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Efficient and secure content-based image Retrieval in Cloud-assisted internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. (2024).

Lo, W. W., Kulatilleke, G., Sarhan, M., Layeghy, S. & Portmann, M. XG-BoT: An explainable deep graph neural network for botnet detection and forensics. Internet of Things, 22, p.100747. (2023).

Ma, J., Su, W., Li, Y. & Peng, Y. Synchronizing DDoS detection and mitigation based graph learning with programmable data plane, SDN. Future Generation Comput. Syst. 154, 206–218 (2024).

Li, K., Zhou, H., Tu, Z., Liu, O. & Zhang, H. AT-GCN: A DDoS attack path tracing system based on attack traceability knowledge base and GCN. Computer Networks, 236, p.110036. (2023).

Qian, K. et al. Distributed Detection of Large-Scale Internet of Things Botnets Based on Graph Partitioning. Applied Sciences, 14(4), p.1615. (2024).

Jemal, I., Cheikhrouhou, O. & Haddar, M. A. October. IoT DOS and DDOS Attacks Detection Using an Effective Convolutional Neural Network. In 2023 International Conference on Cyberworlds (CW) (pp. 373–379). IEEE. (2023).

Abinesh, R. & Nandhini, S. VG, Y., TJ, S. and October. Deep Graph Convolution Neural Network based Intrusion Detection System towards Early Detection of Malicious Attacks. In 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud)(I-SMAC) (pp. 549–554). IEEE. (2024).

Lee, Y. & Han, S. W. CAGCN: Causal attention graph convolutional network against adversarial attacks. Neurocomputing, 538, p.126187. (2023).

Sanap, Y. B. & Aher, P. G. February. Deep Learning Method for Detecting and Mitigating Distributed Denial of Service Attacks with Imbalanced Data. In 2024 International Conference on Integrated Circuits and Communication Systems (ICICACS) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. (2024).

Khalid Alkahtani, H. et al. optimal graph convolutional neural network-based ransomware detection for cybersecurity in IoT environment. Applied Sciences, 13(8), p.5167. (2023).

Saunders, B. J., Kisanga, P., Carvalho, G. H. & Woungang, I. April. A Graph Convolutional Networks-Based DDoS Detection Model. In 2024 IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon) (pp. 1–5). IEEE. (2024).

Kisanga, P., Woungang, I., Traore, I. & Carvalho, G. H. February. Network anomaly detection using a graph neural network. In 2023 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC) (pp. 61–65). IEEE. (2023).

Altaf, T. et al. GNN-Based Network Traffic Analysis for the Detection of Sequential Attacks in IoT. Electronics, 13(12), p.2274. (2024).

Alhayani, S. & Murphy, D. R. A machine learning-based distributed denial of Service Detection Approach for early warning in Internet Exchange points. Computers Mater. Continua, 76(2). (2023).

Thota, M. K., Prathibhavani, P. M. & Venugopal, K. R. June. The Graph Neural Network with Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network for botnet detection in smart city IoT. In 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024).

Barsellotti, L., De Marinis, L., Cugini, F. & Paolucci, F. June. FTG-Net: Hierarchical flow-to-traffic graph neural network for DDoS attack detection. In 2023 IEEE 24th International Conference on High Performance Switching and Routing (HPSR) (pp. 173–178). IEEE. (2023).

Geem, D. et al. Progression of Pediatric Crohn’s disease is Associated with anti–tumor necrosis factor timing and body Mass Index Z-Score normalization. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22 (2), 368–376 (2024).

Alzoubi, S. et al. (2024). Synergistic swarm optimization algorithm.

Alshinwan, M. et al. Enhanced Prairie Dog Optimization with Differential Evolution for Solving Engineering Design Problems and Network Intrusion Detection System. Heliyon. (2024).

Immordino, G., Vaiuso, A., Da Ronch, A. & Righi, M. Predicting Transonic Flowfields in Non-Homogeneous Unstructured Grids Using Autoencoder Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04396. (2024).

Zeng, L., Hu, M., Zhang, C., Yuan, Q. & Wang, S. A Multi-strategy-improved Northern Goshawk optimization algorithm for global optimization and Engineering Design. Computers Mater. Continua, 80(1). (2024).

Becerra-Suarez, F. L., Fernández-Roman, I. & Forero, M. G. Improvement of Distributed Denial of Service Attack Detection through Machine Learning and Data Processing. Mathematics, 12(9), p.1294. (2024).

Fathima, A., Devi, G. S. & Faizaanuddin, M. Improving distributed denial of service attack detection using supervised machine learning. Measurement: Sensors, 30, p.100911. (2023).

Vaisakhkrishnan, K., Ashok, G., Mishra, P. & Kumar, T. G. Guarding Digital Health: deep learning for attack detection in Medical IoT. Procedia Comput. Sci. 235, 2498–2507 (2024).

Ramadass, P. et al. BSDN-HMTD: A blockchain supported SDN framework for detecting DDoS attacks using deep learning method. Egyptian Informatics Journal, 27, p.100515. (2024).

Sedhuramalingam, K. & Saravanakumar, N. A novel optimal deep learning approach for designing intrusion detection system in wireless sensor networks. Egyptian Informatics Journal, 27, p.100522. (2024).

Funding

details.

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R384), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chukka Ramesh Babu: Conceptualization, methodology development, experiment, formal analysis, investigation, writing. M. Suneetha: Formal analysis, investigation, validation, visualization, writing. Mohammed Altaf Ahmed: Formal analysis, review and editing. Palamakula Ramesh babu : Methodology, investigation. Mohamad Khairi Ishak: Review and editing. Samih M. Mostafa: Discussion, review and editing. Hend Khalid Alkahtani: Conceptualization, methodology development, investigation, supervision, review and editing.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The manuscript was written with the contributions of all authors, and all authors have approved the final version.

Ethics approval

This article contains no studies with human participants performed by any authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Affiliation 1 and 2 were not listed in the correct order. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babu, C.R., Suneetha, M., Ahmed, M.A. et al. Hybridization of synergistic swarm and differential evolution with graph convolutional network for distributed denial of service detection and mitigation in IoT environment. Sci Rep 14, 30868 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81116-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81116-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advancements in multimodal differential evolution: a comprehensive review and future perspectives

Artificial Intelligence Review (2025)