Abstract

With the rapid development of the semiconductor industry, Hardware Trojans (HT) as a kind of malicious function that can be implanted at will in all processes of integrated circuit design, manufacturing, and deployment have become a great threat in the field of hardware security. Side-channel analysis is widely used in the detection of HT due to its high efficiency, non-contact nature, and accuracy. In this paper, we propose a framework for HT detection based on contrastive learning using power consumption information in unsupervised or weakly supervised scenarios. First, the framework augments the data, such as creatively using a one-dimensional discrete chaotic mapping to disturb the data to achieve data augmentation to improve the generalization capabilities of the model. Second, the model representation is learned by comparing the similarities and differences between samples, freeing it from the dependence on labels. Finally, the detection of HT is accomplished more efficiently by categorizing the side information during circuit operation through the backbone network. Experiments on data from nine different public HTs show that the proposed method exhibits better generalization capabilities using the same network model within a comparative learning framework. The model trained on the dataset of small Trojan T100 has a detection efficiency advantage of up to 44% in detecting large Trojans, while the model trained on the dataset of large Trojan T2100 has a detection efficiency advantage of up to 10% in detecting small Trojans. The results in data imbalanced and noisy environments also show that the contrastive learning framework in this paper can better fulfill the requirements of detecting unknown HT in unsupervised or weakly supervised scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

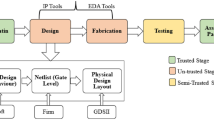

In recent years, with the rapid development of a new generation of information technology, FPGA has been more widely used in high-performance computing, 5G, artificial intelligence, Internet of Things and other fields. Ali Cloud, Tencent Cloud, Baidu Cloud and others have deployed FPGA-based cloud acceleration servers, and Microsoft has used FPGAs to accelerate Bing search, and the issue of hardware security is gradually being paid attention to by academia and industry. Hardware Trojans (HT) are different from software viruses, which can be cleaned from the system. HT, once implanted, can lurk for a long period of time, stealing information and destroying circuits. In the design and manufacturing stage of FPGA chips, third-party IP cores are usually used, and these untrustworthy third-party IPs have the risk of introducing HT1. At the same time, general chip manufacturing and assembly are usually outsourced to other factories, which also greatly increases the possibility of FPGA devices being implanted with HT2. Secondly, in the process of FPGA application development, the attacker can realize the implantation of hardware trojan at several stages, such as, modifying the Register Transfer Level (Register Transfer Level) code, synthesis netlist, and layout wiring netlist. Finally, during the application of FPGA, the attacker can even modify the bitstream file to implant the Trojan3. Therefore, the identification and detection of HT are critical throughout the life cycle of hardware device design, manufacturing, deployment and operation.

It has been more than 10 years since the concept of hardware trojan was first proposed, and scholars at home and abroad have carried out extensive research in hardware trojan and its related fields, mainly for logic testing and side-channel analysis, etc. Side-channel analysis technology4,5,6,7,8,9 is to complete the detection of hardware trojan in the chip by extracting and analyzing the characteristic information of the chip’s power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, or time delay, which has rapidly become a research hotspot in the domestic and international security field due to its short cycle, non-destructive, and high efficiency characteristics. In 2007, Agrawal et al.2 proposed a hardware trojan analysis method using the side-channel of the chip to establish a "power consumption fingerprint". 2011, Zhang et al.10 proposed a hardware trojan detection technique based on ring oscillator network. In 2012, Wang et al.11proposed a transient power-based hardware trojan detection method, which realizes Trojan detection by processing power consumption values through a singular value decomposition algorithm. The team later also implemented trojan detection techniques based on techniques such as Mahalanobis distance12and genetic algorithm13 in 2013 and 2016. In 2014 and 2017 Yu et al.14,15 proposed a processing method based on the K-L transform, which initially and effectively delineates the difference between the trojan chip and the standard chip-side channel information. In 2016 Kitsos et al.16 proposed the application of an order-variable ring oscillator to FPGA hardware trojan detection. 2016 Shende et al.17 proposed a hardware trojan detection method for power-side channel combining Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). 2016 Wang et al.18 proposed an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM)-based hardware trojan detection technique. 2017 Adokshaja et al.19 projected high-dimensional bypass signal feature data to a low-dimensional space via benchmark metrics and identified combinatorial Trojans that accounted for about 3% of the circuit. 2017 Xue et al.20 used a hardware trojan detection method based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) combined with Mahalanobis Distance to efficiently detect a parent circuit area of about 0. 6% of the HT. 2019 Hu et al.21 used side-channel analysis (SCA) and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers to determine the presence of HT in circuits. 2021, Wen et al.22 proposed a non-destructive technique based on heatmaps and Inception neural networks. The method generates heat maps of a Trojan-free IC chip and multiple simulated Trojan-infected IC chips, which are optimized as critical-side channel leakage. Subsequently, these optimized heatmaps are analyzed by Inception neural network, which can accurately extract the embedded Trojans with the assistance of custom filters. 2022, Sun et al.23 proposed a new method for hardware trojan detection by transfer learning using electromagnetic side channel signals. The method uses continuous wavelet transform and transfer learning to extract the time–frequency information of electromagnetic signals, which fully utilizes the useful information in the time and frequency domains. Subsequently, the key features are classified by support vector machines, which effectively improves the accuracy of detection. 2023, Hassan et al.24 proposed an integrated circuit topology and behavior-aware hardware trojan detection method. The method combines these features with behavioral information by extracting different structural features and behavioral information of the underlying integrated circuits, which are used together for Trojan detection analysis. Although hardware trojan detection techniques based on side-channel analysis have emerged in recent years, the following problems still exist.

-

1.

Although unsupervised learning-based hardware trojan detection does not require labeled dataset training data, the lack of labeling information makes the unsupervised learning lack the iterative process of feedback and updating similar to supervised learning, which directly leads to the poor performance in the actual detection task.

-

2.

Although hardware trojan detection based on supervised learning can accomplish the task of hardware trojan detection more accurately through labeled datasets, it is time-consuming and cumbersome to obtain labeled datasets in the face of massive data in the actual detection task.

-

3.

During training, the model becomes overly dependent on the training dataset and is bound by labels limiting the model’s ability to feature extraction, which results in the model functioning only on specific datasets and performing poorly when faced with unknown datasets.

In this paper, we firstly introduce the contrastive learning in the field of computer vision to the field of side-channel hardware trojan detection and propose a hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning to make up for the deficiencies in the above problems. The specific contributions of the hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning are as follows.

-

1.

The contrastive learning framework draws on the training mechanism of supervised learning, where the differences and similarities between samples constitute a loss through which feedback is accomplished and the weights of the network model are iteratively updated, allowing the network to learn a high-quality feature representation of the data.

-

2.

The contrastive learning framework utilizes the self and mutual differences of different categories of data to learn the features of the data itself, without the need for manual labeling. Therefore, it is suitable for learning large-scale unlabeled data and avoids the time cost and difficulty of obtaining labels when facing massive data.

-

3.

The contrastive learning framework is different from supervised learning in that it uses data augmentation techniques to generate diverse pairs of samples, and the nature of the sample pair training process is to learn the differences and characteristics of different classes of data which effectively reduces the risk of model overfitting. Since the complex and random dynamical behavior of chaos trajectories in phase space allows the data to accomplish more complex nonlinear changes, this paper introduces data augmentation techniques such as discrete chaotic mapping disturbances to significantly improve the model’s generalization capabilities.

The second part briefly introduces HT, deep learning based hardware trojan detection techniques for side-channels. In the third part, we propose a hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning and describe the data augmentation method and unsupervised learning process in detail. In the fourth part, the hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning is compared with other unsupervised learning and self-supervised learning methods for experiments on detection accuracy of public HT with different functions and sizes. We summarized the entire article in the fifth part.

Preliminaries

Hardware trojans

HT are special modules deliberately implanted in a chip or electronic system or defective modules left unintentionally by the designer. In order to avoid detection, trojans are usually designed as small-sized, not easily triggered circuits, hidden in the original design. HT are mainly divided into two parts: the trigger logic part and the payload part. Its main structure and working principle is shown in Fig. 1. trojan in the vast majority of cases is in a dormant state, this state does not affect the normal operation of the circuit. Triggered by special conditions, the inserted hardware trojan may lead to leakage of information, change the function of the circuit, or even destroy the circuit.

The vast majority of hardware trojan examples in the hardware trojan Circuit Library come from the Trust-Hub website. There are a total of 21 Trojans in the Trust-Hub Trojan Library that are used in AES designs. Three of these Trojans (AES-T500, AES-T1800, and AES-T1900) directly attack the battery life of the power supply belonging to the main circuit. The other 18 perform some sort of data leakage, thus damaging the integrity of the circuit. The percentage of Trojan area ranges from 0. 19% to 1. 15%. The T100 has the smallest Trojan area, with a ratio of inserted Trojan modules to total circuit area of 0. 19%. The T2100 has the largest Trojan area, with a ratio of Trojan modules to total circuit area of 1. 15%. The energy-consuming Trojan, exemplified by the T500, was activated after observing a specific sequence of input plaintext. The payload of the Trojan is a shift register that continues to run after the Trojan is activated, causing a sharp rise in circuit power consumption. The leakage circuit of an information-leaking trojan, exemplified by the T600, consists of a shift register that holds the key and two inverters. After detecting a specific input plaintext, the Trojan leaks the AES-128 key through the leakage electric current. The functions and Trojan area share of some models of HT in the Trust-Hub Trojan library are shown in Table 1.

Hardware trojan detection based on deep learning and side-channel analysis

Hardware trojan detection technology is an emerging research hotspot, hardware trojan detection technology is categorized into intrusive and non-intrusive detection. The current detection methods mainly include reverse engineering, logic testing, hardware trojan detection by side-channel analysis and trustworthiness design. Hardware trojan detection by side-channel analysis is widely concerned by scholars at home and abroad because of its advantages of high efficiency, non-contact and high accuracy. The implantation of hardware trojan will modify or increase the structure of the original circuit, so it will change the parameter characteristics such as power consumption or delay of the circuit. Hardware trojan detection technology using side-channel information such as timing or power consumption during circuit operation to detect the trojan, this detection method does not need to activate the trojan circuit. If the proportion of hardware trojan circuits is relatively large, the trojan has a large impact on the power consumption of the circuit, the trojan circuits can be easily determined through the power consumption information, on the contrary, the circuit increases the power consumption information is very easy to be drowned out by the noise.

Convolutional neural networks

Convolutional neural network is one of the most classical algorithms in deep learning. The powerful feature learning function of convolutional neural networks has led to its great success in many research areas nowadays, such as natural language processing25,26, image classification27,28, face recognition29,30, speech recognition31,32, etc. CNNs use a form of local connectivity and parameter sharing to optimize the redundancy of network parameters and to simplify the model complexity. The feature extraction capability of the network is thus enhanced, the risk of overfitting is avoided, and the network is more easily optimized.

CNNs mainly use Convolutional Layer, Pooling Layer and Fully Connected Layer to extract features for classification, recognition and localization. The convolutional layer is the core layer in CNN, which extracts local features and preserves spatial structure. The convolution operation can be regarded as a sliding convolution kernel, and the convolution kernel is operated with its corresponding position to obtain a feature point, which eventually forms a feature map. The pooling layer is used to reduce the size of the feature map and the number of parameters, and the common pooling methods are max pooling and average pooling. The fully connected layer is used to transform the feature map into a classification result or output target location. A more detailed description of the common unit modules and functions in the CNN structure is given below, where Fig. 2 shows the classical ResNet residual neural net work.

A. Convolutional layer

The convolutional layer is the core component of the model compared to other components of the convolutional neural network and is also known as the feature extraction layer. The convolutional layer extracts features from the input data, and it obtains the feature map by dot product and accumulation between the convolutional kernels and the original image, thus achieving feature extraction. The parameters of the convolution layer include the size, depth (the number of convolution kernels), stride, and padding of the convolution kernel. By adjusting these parameters, the output size and depth of the convolutional layer can be controlled to adapt to different input data and task requirements. The convolution operation is shown in Formula (1).

where \(W\) represents the weight matrix of the convolution module and \(b\) represents the bias value.

B. Activation function

The activation function layer in CNN is usually added after each convolutional and fully connected layer to map the solution of the problem to a nonlinear space to increase the expressiveness and nonlinear fitting ability of the network. In CNNs, the use of activation function layers has an important impact on both the training and performance of the network. Appropriate selection of activation functions can help the network better approximate the objective function, speed up the convergence of the network, and improve the generalization capabilities of the network, as well as reduce the occurrence of problems such as gradient disappearance.

The commonly used activation functions in CNN include sigmoid function, tanh function, ReLU function, LeakyReLU function, ELU function and so on. All of these activation functions have nonlinear characteristics, and different activation functions have different roles and characteristics. Among them, ReLU function is widely used in CNN because it is simple and easy to compute, and can improve the training speed of the network by fast convergence. ReLU function is shown in Formula (2).

where \(\text{x}\) represents the input value. \(\upsigma (\bullet )\) represents the activation function ReLU, which maps all negative values to zero while keeping positive values constant.

C. Pooling layer

The pooling layer is a common layer in convolutional neural networks, usually behind the convolutional layer and the activation function, and its process is similar to the channel-by-channel convolution mentioned above. Pooling layers reduce the size of the data by downsampling the input data while preserving the main features of the data, and help the network to greatly reduce the redundancy of parameters, thus speeding up training and prediction. There are two common types of pooling layers, including max pooling and average pooling. Max pooling reduces the size of the data by selecting the largest value in each window, while average pooling reduces the size of the data by calculating the average of all values in each window. The maximum pooling and average pooling are shown in Formulas (3) and (4), respectively.

where \({\text{y}}_{\text{i},\text{j}}\) is the output of pooling and \({\text{x}}_{\text{i}+\text{m },\text{ j}+\text{n}}\) is the input to the pooling window. \(\text{m}\) and \(\text{n}\) are the offsets of the pooling window.

D. Fully connected layer

The fully connected layer is a common neural network layer in CNN, also known as the dense layer. The fully connected layer contains many neurons, and each neuron in this layer is interconnected with all neurons in the previous layer. In CNN, the fully connected layer usually appears in the last layer of the network after several convolutional and pooling operations, usually using one or more fully connected layers to aggregate the extracted local feature information, transform the learned feature map into a one-dimensional vector, and map it to the labeled space of the data.

E. Residual module

Typically used in deep neural networks, the residual module is an architecture proposed by He et al. in 2015. In a residual module, which usually consists of a series of convolutional layers, a batch normalization layer, and an activation function, a residual connection is additionally introduced, where the residual connection is a jump connection. It allows information to flow through the network in a “shortcut” way, allowing the network to learn the residual information, which helps to alleviate the problems of gradient vanishing and gradient explosion, and thus train the deep network more efficiently. The computation process of the residual module is shown in Formula (5).

where \(x\) is the input, \(F(x)\) is the output of the primary path, and \(y\) is the output of the residual module. \({W}_{1}\) and \({W}_{2}\) represents the weight matrix of the convolution module and \({b}_{1}\) and \({b}_{2}\) represents the bias value. \(\upsigma (\cdot )\) represents the activation function.

Implementing hardware trojan detection based on deep learning and side-channels analysis

Hardware trojan detection based on deep learning and side-channel analysis can reach the purpose of detecting hardware trojan circuits by simply constructing a classification model according to the above public modules and network structure, and the detailed flow of training and deployment of the classification model is given below.

-

Preparing the dataset. The dataset for the hardware trojan detection task uses the power consumption information generated during the operation of the algorithm as the input data, which is labeled 0 and 1 (0 for data without hardware trojan and 1 for data with hardware trojan).

-

Construct network models. According to the above basic module, we can customize a suitable network model according to the task requirements or use the existing mature classification models such as GoogLeNet, ResNet and Yolov series of network models. The mature classification model can randomly initialize the weights or use the pre-trained weight parameters of the model in other tasks. Classification models are typically used at the output layer with a sigmoid activation function that maps the output values to a probability distribution ranging between \([\text{0,1}]\) so that they can be interpreted as probabilities. sigmoid activation function is shown in Formula (6).

where \(x\) represents the input value. \(\sigma (x)\) represents the probability that the input value \(x\) maps to the interval \([\text{0,1}]\).

-

Define the loss function. Define the loss function applicable to the classification task, where the cross-entropy loss function calculates the loss based on the cross-entropy between the distributions is particularly applicable to the binary classification problem in the hardware trojan detection task. The binary cross-entropy loss function is shown in Formula (7).

where \({y}_{i}\) is the true labels (0 or 1) of the ith sample. \({p}_{i}\) is the probability that the model predicts that the sample belongs to category 1. \(N\) is the number of samples in the dataset.

-

Optimizer selection. The optimizer updates the weights and biases in the network model based on the losses, different optimizers are suitable for different scenarios and tasks, so it is necessary to choose the appropriate optimizer and parameters.

-

Training models. The dataset is input into the network structure, and the hardware trojan detection model is finally trained by updating the weights to reduce the loss through back-propagation continuous iterative optimization.

-

Deployment model. In the actual hardware trojan detection task only need to input the power consumption information generated during the operation of the device to be detected into the trained model to complete the detection of hardware trojan.

Algorithm 1 describes a hardware trojan detection algorithm based on deep learning and side-channel analysis in pseudocode. \({t}_{train}\) represents the training dataset consisting of power traces \({t}_{TJFree}\) of Trojan-free circuits and power traces \({t}_{TJ}\) of Trojaned circuits. \(label\) represents the corresponding labeled dataset of the training dataset, where 0 represents a Trojan-free circuit and 1 represents a Trojan circuit. \(\text{module}(\cdot )\) represents the network architecture used for hardware trojan detection. \(\text{BCELoss}(\cdot )\) represents the binary cross-entropy loss function as shown in Formula (7). The return value \(classification\) of the algorithm is 0 means that the circuit does not contain Trojan circuits, and the return value \(classification\) is 1 means that the circuit contains Trojan circuits, so as to complete the detection of hardware trojans.

Although hardware trojan detection based on deep learning and side-channel analysis performs well in real-world detection tasks, but it still faces multiple challenges. First, deep learning methods usually rely on large amounts of labeled data to train models. This is particularly true in the field of hardware trojan detection due to the high cost and difficulty of obtaining labeled data. The scarcity of labeled data not only limits the training scale and performance of the model, but also affects its application and generalization capabilities in real scenarios. Second, deep learning models are often viewed as complex black-box models, which means that their internal decision processes are difficult to explain. This lack of interpretability not only increases the difficulty of deploying and debugging the models, but also limits the trustworthiness and validation of the model outputs. In security-sensitive hardware environments, understanding the model’s decision-making process is critical, as there is a need to ensure that the model not only performs well, but is also able to effectively explain and interpret its detection results.

As a result, these challenges faced by deep learning methods in hardware trojan detection limit their widespread use and effectiveness in real-world applications. To overcome these problems, we propose a hardware trojan detection framework utilizing SimCLR-based contrastive learning to reduce the dependence on labeled data, and improve model interpretability, thereby bringing new breakthroughs and application possibilities in the field of hardware trojan detection.

Hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning

In this paper, contrastive learning33,34,35,36,37,38 is selected as the methodology due to its significant advantages and innovative potential in hardware Trojan detection. Compared to supervised learning methods, contrast learning utilizes a contrast loss function to enable effective training in unsupervised or weakly supervised scenarios, thus significantly reducing the dependence on large amounts of labeled data. This is particularly important because in the field of hardware security, obtaining sufficient quantity and quality of labeled data is often difficult and expensive. Another expected advantage of contrastive learning is its ability to improve the detection of unknown HT attacks by learning internal structures and patterns in the data. While traditional machine learning techniques may be limited by known attack patterns, contrastive learning methods are able to adaptively recognize novel threats without prior knowledge of attack characteristics. This flexibility and adaptability allows contrastive learning to excel in the face of dynamic and complex hardware environments and to better cope with security threats. Therefore, in this paper, we choose contrastive learning as the main framework for HT detection methods, aiming to overcome the limitations of traditional methods and improve the accuracy and efficiency of detection while reducing the implementation cost.

In the field of computer vision a variety of contrastive learning methods are emerging, among which in 2020 Chen et al. proposed a simple and effective learning framework SimCLR39. SimCLR learns by maximizing the similarity of the same image and minimizing the similarity of different images through data augmentation. In this paper, SimCLR is used as a blueprint to extend the original three-dimensional image problem in the field of computer vision to the one-dimensional time series task in the hardware trojan detection problem. A detailed description of each unit module and function in the hardware trojan detection framework based on contrastive learning is given below, where Fig. 3 shows the complete hardware trojan detection framework diagram based on contrastive learning.

Data augmentation

The representation learning phase of contrastive learning is actually a process of determining similarities and differences, and it is natural to prepare positive and negative samples, and then learn the relationship between positive samples and the relationship between negative samples. Therefore, the first task is how to define the positive and negative samples. Positive and negative samples for contrastive learning are no longer defined in the form of labels but are automatically randomly generated through different ways of data augmentation. The same sample obtained by different ways of random augmentation is the positive sample. The samples obtained from different samples by different ways of random augmentation are negative samples. Negative samples effectively increase the difficulty of model learning in the representation learning stage, because it is necessary to learn different features with all negative samples, the more negative samples under the same batch, the more difficult it is for the model to learn. For a dataset containing \(n\) side information, the number of pairs of positive samples is 2 \(n\) and the number of pairs of negative samples is \(2n(n-1)\).

There is a wide variety of data augmentation for images in the field of computer vision, and the greater the difference in samples obtained after data augmentation, the better the modeling effects. However, the means of data augmentation for one-dimensional time series are extremely limited. In order to systematically study the impact of data augmentation, this paper considers several common methods. The data augmentation methods defined in this paper include shift operations, low-pass filters, scaling operations, and the addition of Gaussian white noise. In order to stimulate the learning ability of the model and make the samples obtained after data augmentation show significant differentiation, this paper proposes to introduce interpolation and discrete chaotic mapping to perturb the input data, in which the discrete chaotic mapping makes the augmented data show significant differentiation due to its own excellent nonlinear dynamics. The following is a detailed description of the data augmentation scheme we use in this framework. Figure 4 shows the effect of data augmentation that we have investigated in this work. The top figure shows the raw trace and the bottom figure shows the power trace after data enhancement. The horizontal axis represents the sampling point of the power trace and the vertical axis represents the power consumption value of the power trace.

The shift operation creates new samples by shifting the input samples horizontally so that the model is not affected by the position of features in the side information when detecting HT. The shift operation defined in this paper randomly selects either left or right shift, and the shift range is \(m/2\) of half of the number of sampling points \(m\). The left shift operation of the samples is shown in Formula (8), and the right shift operation is similar to the left shift operation.

where \(t\) denotes a sample, \({t}{\prime}\) denotes a randomly shifted sample, and \(\text{randint}(\cdot )\) denotes a random integer within the corresponding range of values.

Low-pass filtering creates new samples by filtering out the high-frequency noise in the side information and retaining the low-frequency valid information, which makes the waveform smoother as a whole. The attenuation factor for low-pass filtering defined in this paper is randomly selected in the interval of \([\text{0.3,0.7}]\). The low-pass filtering of sample t is shown in Formula (9).

where \({t}_{i}\) denotes the i-th sampling point in the sample and \({t}_{i}{\prime}\) denotes the i-th sampling point of the sample after data augmentation.

Random scaling is used to increase the diversity of data by scaling the magnitude of the original side information. The scaling factors \(\beta\) defined in this paper are randomly selected in the interval \([\text{0.3,0.7}]\). The random scaling of the samples is shown in Formula (10).

Noise-based data augmentation increases the diversity of the data by injecting Gaussian noise into the original side information in this way. The Gaussian noise defined in this paper has a mean of 0 and a variance of 0. 01. The noise-based data augmentation of the sample is shown in Formula (11).

where \(randn(1,m)\) denotes m random values in the interval \([\text{0,1}]\).

The interpolation operation inserts additional new samples between the samples with power consumption information. In the interpolation operation defined in this paper, the samples after data augmentation shave off the original power consumption information to create new samples using the newly inserted data. The interpolation based data augmentation of the samples is shown in Formula (12).

where \(interp(\bullet )\) denotes the interpolation operation.

Discrete chaotic mapping with its complex dynamical behavior, nonlinearity and randomness allows the original side information to show significant differentiation. The discrete chaotic mapping defined in this paper uses a one-dimensional Logistic discrete chaotic mapping. The discrete chaotic mapping of the sample is shown in Formula (13).

where the parameter \(\varphi\) is in the interval \([3.569945\text{6,4}]\), the system enters a chaotic state,so \(\varphi\) is chosen randomly in the interval.

To understand the importance of data augmentation being combined, we investigate the performance of our framework when paired data augmentation is performed. Figure 5 shows the assessment results under different combinations of data augmentation. The horizontal and vertical axes represent different data augmentation methods, and the matrix block formed by the two shows the percentage of normal and malicious hardware circuits that are correctly classified by the model after the corresponding combination of data augmentation methods. The legend goes from yellow to purple, indicating a gradual increase in HT detection accuracy rate. We observe that one of the combinations stands out: logistic mapping and random scaling. Thus in order to learn scalable features, it is crucial to combine logistic mapping and random scaling.

Encoder

Different samples expanded by data augmentation will be fed into the encoder thus capturing local and global features of the input data. The encoder can be a fully connected network, a convolutional neural network or a Transformer. In this paper, ResNet residual network is used as the encoder in contrastive learning. In the representation learning phase, the encoder is distinguished from supervised learning in contrastive learning using unlabeled datasets to learn a representation of the data. The encoder, in combination with the loss function mentioned subsequently, brings similar samples closer and closer together in the feature space, while different samples are as far away as possible in the feature space. In the downstream task phase, the structure and parameters of the backbone network shared in the representation learning phase are used as the feature extraction module and fine-tuned as such to complete the classification network for hardware trojan detection.

Projection head

The encoder encodes the data augmented samples and feeds them into the projection head, which in turn maps to another space to help the model learn the more differentiated features of the samples, thus improving the performance of the entire contrastive learning framework. The projection head usually consists of one or more fully connected layers with nonlinear activation functions embedded in the middle. The projection head is shown in Formula (14).

where \({y}_{encoder}\) denotes the output vector after encoding by the encoder and \({y}_{ph}\) denotes the output vector characterized by the projection head. \(FC(\cdot )\) denotes the fully connected layer and \(ReLU(\cdot )\) denotes the nonlinear activation function ReLU.

Loss function

Both input samples are characterized into a single output vector by means of a projection header, which in turn computes the similarity between the positive and negative example samples by means of a loss function. The purpose of the loss function is to maximize the similarity between the positive samples while minimizing the similarity between the negative samples and the other negative samples. In turn, updating the weights and biases of the encoder through backpropagation allows the network to better understand the features of the input data and the encoder to extract more comprehensive and detailed features. We use NT-Xent loss function (Normalized Temperature-scaled Cross-Entropy) to calculate the similarity between samples. NT-Xent loss function is shown in Formula (15).

where \({z}_{i}\) and \({z}_{j}\) denote the representation vectors of samples of the same class and \({z}_{k}\) denotes the representation vectors of other negative samples, respectively. The numerator considers samples of the same class while the denominator considers samples of different classes. \(n\) denotes the number of samples and \(\tau\) denotes a temperature parameter that is used to amplify the difference between values and the gradient to make the model converge faster. \(sim(\cdot )\) denotes the cosine similarity function as shown in Formula (16).

where \({{z}_{i}}^{T}{z}_{j}\) denotes the inner product of \({z}_{i}\) and \({z}_{j}\), and \(\Vert {z}_{i}\Vert\) and \(\Vert {z}_{j}\Vert\) denote the modulo operations of \({z}_{i}\) and \({z}_{j}\), respectively.

Algorithm 2 describes the framework’s main learning algorithm in pseudo-code. \(Augmentation\_functions\) represents the set of the above six data augmentation methods, where shift, filte, scale, noise, interpolate and logistic are shown in Formula (8–13), respectively. \(\text{random}.\text{choice}(\cdot )\) represents the random selection of data augmentation methods in the set \(Augmentation\_functions\). \(\text{encoder}(\cdot )\) represents feature extraction module, ResNet residual network is used in this paper. \(\text{projection}\_\text{head}(\cdot )\) represents projection head, where the projection head consists of FC network and ReLU activation function as shown in Formula (14). \(\text{NTXent}(\cdot )\) represents NT-Xent loss function as shown in Formula (15) and (16) is used to calculate the similarity between samples.

Experiment and analysis

Experimental setup

The experimental platform is constructed around a SAKURA-G development board designed specifically for hardware security research and development. This FPGA is designed with a power consumption acquisition module, which facilitates the experimenters to collect and process the power consumption information during the operation of the chip. It consists of two processing chips, the xc6slx75 chip of Xilinx’s spartan-6 series and the xc6slx9 chip of the spartan-6 series. The main chip xc6slx75 is responsible for the algorithm module, and the xc6slx9 chip is responsible for communicating with the computer and transmitting information such as plaintexts, keys, random numbers and ciphertexts. Inside the board, a shunt resistor is connected between the VDD line and the GND line, and an SMA socket is soldered to measure the power consumption traces when the chip is running. The power consumption information is then captured by a PicoScope 3000 series oscilloscope and transmitted to the control computer for further analysis. The configuration of the power consumption acquisition platform is shown in Fig. 6.

The Trust-Hub trojan library contains 21 trojans for AES design. The experiments in this paper use the officially provided AES algorithm on the SAKURA-G development board, thus capturing the leakage of power consumption information due to the algorithm operation and HT. Each trace contains 2,300 samples covering a complete cryptographic operation. In order to greatly determine the performance of the proposed method in detecting Trojans, we therefore select nine different sizes of Trojan circuits from small to large depending on the proportion of Trojan circuit area in the whole circuit. Therefore, AES-T100, AES-T700, AES-T800, AES-T500, AES-T1900, AES-T1600, AES-T600, AES-T200, and AES-T2100 circuits are selected as the benchmark in the experiment.

In our experiments, the positive samples are circuit samples that have been implanted with a hardware trojan. The behavior of the circuit of a positive sample will differ from that of a normal circuit, and this difference can manifest itself as abnormalities in current consumption, signal delays, and so on. The negative samples are circuit samples that have not been implanted with hardware trojans. The data from negative samples is used to train models to understand the behavioral patterns of normal circuits. Based on positive and negative samples there are four basic indicators TP, FN, TN, FP used to evaluate the classification results as shown in Table 2. TP denotes the number of Trojan circuits identified as Trojan circuits. FN is the number of normal circuits misidentified as Trojan circuits. TN is the number of normal circuits identified as normal circuits, and FP is the number of Trojan circuits misidentified as normal circuits. In this study, we evaluate the diversity performance of the detection model through the following eight evaluation indexes based on the above four basic indexes.

-

True Positive Rate (TPR). The percentage of circuits containing trojans that are correctly identified. A high truth positive rate represents that the model can effectively capture the malicious hardware in the circuits and reduce the under-reporting. The true positive rate is calculated as shown in Formula (17).

-

True Negative Rate (TNR). The percentage of circuits that do not contain Trojans that are correctly identified. A high truth negativity rate repre sents that the model has a strong recognition ability in detecting non-malicious hardware and effectively reduces false reports. The true negative rate is calculated as shown in Formula (18).

-

False Positive Rate (FPR). Percentage of samples that are actually in the negative category that are misclassified as positive. A low false positive rate means that the system rarely misclassifies non-malicious hardware as malicious when detecting it. The false positive rate is calculated as shown in Formula (19).

-

False Negative Rate (FNR). The percentage of samples that are actually in the positive category that are incorrectly categorized as negative. A low false-negative rate means that the system rarely misses detecting truly malicious hardware when detecting non-malicious hardware. The false negative rate is calculated as shown in Formula (20).

-

Acuracy rate. The percentage of circuits correctly categorized by the detection model. A high accuracy rate represents that the model is able to effectively differentiate between normal and malicious hardware circuits. The accuracy rate is calculated as shown in Formula (21).

-

Precision Rate. The percentage of circuits detected as Trojan circuits that are actually Trojan circuits. A high accuracy rate represents that the model has a low false alarm rate. The accuracy rate is calculated as shown in Formula (22).

-

F1 score. A combination of the true positive rate and the precision rate, which is the reconciled average of the two.The F1 score is calculated as shown in Formula (23).

-

Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (ROC) and Area Under the Curve (AUC).The ROC curve is a curve with false positive rate as the horizontal axis and true positive rate as the vertical axis.The AUC value is the area under the ROC curve and represents the overall performance of the model.The closer the ROC curve is to the upper left corner and the closer the AUC value is to 1, the better the model performance.

Hardware trojan detection experiment based on contrastive learning framework

In this experiment, we train the model using 10,000 power traces without and with HT, respectively. The network is trained using an Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1E—3, a mini-batch size of 32, and a maximum number of iterations of 100.

In this section, we randomly select 100 sets of data in the validation dataset of different types of HT, where 50 sets are power traces without HT circuits and 50 sets are power traces with HT circuits, and output the probability distributions of the input data belonging to each category through the contrastive learning framework. A visualization of these probability distributions is shown in Fig. 7, where 0.5 was chosen as the decision boundary, the reason for this is because binary classifiers used for hardware trojan detection typically output a probability value ranging from 0 to 1. 0.5 is the middle value of this range, indicating that the classifier is neutral about the likelihood of the sample belonging to the two categories (trojan and trojan-free) is neutral. If the output is greater than 0.5, it means that the sample is more likely to belong to the trojan category. If it is less than 0.5, it is more likely to belong to the trojan-free category. This symmetry and neutrality makes 0.5 a natural decision boundary.

As can be seen in Fig. 7, the probability distribution of the power consumption information shows a clear distinguishable clustering in the interval [0,1], the probability value of the circuit that does not contain HT is closer to 0, while the probability value of the circuit that contains HT is closer to 1, which represents the fact that the HT detection framework based on contrastive learning proposed in this paper can efficiently detect HT lurking in encrypted circuits with different functions and sizes. However, as shown in Fig. 7 due to the proportion of HT in the whole circuit is too small, hidden design or low activity in the Trojan detection task of T100, T700, T800 and T2100 can be seen in the presence of some probability distribution abnormal data and detection errors.

Comparison with HT detection methods

In order to validate the detection capability of the model for HT, in this section we conduct parallel comparison experiments using six existing clustering algorithms based on unsupervised learning, five machine learning algorithms based on supervised learning, and four classification models based on deep learning, respectively.

In our experiments, we compared the TPR, TNR, and accuracy of our proposed method with those of existing techniques. Since neither TPR nor TNR alone is sufficient to illustrate the effectiveness of HT detection methods, to visualize the results more, we show the stacked histograms of each algorithm in different sizes of HT detection tasks in Fig. 8, where the light green color represents the TPR, the dark green color represents the TNR, and the sum of the two represents the accuracy rate. Among the clustering algorithms based on unsupervised learning, K-Means and K-Medoids show better HT detection efficiency by assigning center of mass to form clusters based on distance. However, we can observe that DBSCAN has detection anomalies when detecting some HT. This is due to the fact that DBSCAN determines the category based on the density of the core object’s neighborhood. However, DBSCAN also takes into account some anomalous sampling points or a small number of floating out-of-cluster sampling points that do not have a density reachable relationship with any core object, which leads to the possibility that DBSCAN may generate more than 2 clusters, thus failing to accomplish the HT detection task. In supervised learning based machine learning algorithms, SVM separates different classes of data points by finding an optimal hyperplane in a high dimensional space. This makes it effective in distinguishing Trojan circuits from each other. Among deep convolutional neural networks, ResNet shows strong TPR, TNR, and accuracy in HT detection thanks to its powerful deep feature extraction and nonlinear representation. Our proposal shows better detection efficiency than most of the detection methods in terms of TPR, TNR and accuracy in different HT scenarios, but due to its unsupervised nature, the detection efficiency is only slightly inferior to that of the supervised ResNet based.This is a very good performance for unsupervised HT detection.

In our experiments, our proposed FPR and FNR are compared with other existing techniques, and in order to visualize the results more, we show the stacked histograms of each algorithm under different sizes of HT detection tasks in Fig. 9, where the light green color represents the FPR and the dark green color represents the FNR . In HT detection, the combination of low FPR and low FNR ensures that the detection method can both accurately identify malicious circuits and avoid misjudging normal circuits, thus improving the effectiveness and reliability of HT detection. As shown in the figure, clustering algorithms based on unsupervised learning lack labeling information to guide the model’s learning process, forcing them to rely on the inherent structure of the data to form clusters. Meanwhile, supervised learning-based machine learning algorithms such as KNN and Naive Bayes are weak in feature extraction and representation for high-dimensional and complex data such as hardware trojan behaviors, and it is difficult to capture complex Trojan behavioral patterns, which leads to the poor performance of both of them in terms of FPR and FNR. Whereas, ResNet undoubtedly still shows good detection efficiency in both FPR and FNR. Our proposal also ensures the reliability of hardware trojan detection methods with very low FPR and FNR.

In the experiments, our proposal is compared with other existing methods in terms of precision rate and F1 score, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. A high precision rate means that the model is able to accurately identify malicious circuits and minimize the misclassification of normal circuits as malicious.The F1 score evaluates the model’s accuracy and recall in a comprehensive manner. A high F1 score indicates that the model is able to recognize malicious circuits with both accuracy and comprehensiveness which means that it is able to distinguish malicious circuits efficiently and misclassify normal circuits as malicious as little as possible. ResNet shows perfect performance in terms of precision rate and F1 score. The precision rate of our proposal in different HT scenarios is close to 100% while the F1 score is closer to 1. This proves the high reliability, low false alarms, and balanced detection performance of our scheme.

In the experiments, we compare the ROC curves and AUC values of our detection framework with those of other supervised learning-based models, as shown in Fig. 10 and Table 5. Figures 10 illustrate the performance of the model under different decision thresholds, where each point represents the TPR and FPR under a specific threshold.The area enclosed by the ROC curves is the corresponding AUC value, which is used to quantify the overall performance of the model.The AUC value ranges from 0.5 to 1, with a larger value indicating that the model is more discriminative.An AUC value of 0.5 indicates that the model performs as well as a random guess, while a value of 1 indicates that the model perfectly classifies all positive and negative samples.The AUC value combines all possible thresholds and avoids the limitation of choosing a single threshold. It can be observed in the figure that the ROC curves of this paper’s framework in hardware trojan scenarios of different sizes are all close to the upper left corner, and their AUC values are all close to 1, which is only slightly inferior to that of the ResNet residual network based on supervised learning. This indicates that the framework in this paper has strong classification ability, low false alarm rate and high trustworthiness.

To further validate the resource consumption, scalability, and computational efficiency of the contrastive learning framework, we compared the performance of the model with other network models in terms of the number of trainable parameters and runtime complexity. The number of model trainable parameters is usually used to assess the complexity of the model or the demand of computational resources, so the experiments were performed by traversing all parameters of the network model to sum up the parameters that need to undergo gradient updating. The runtime complexity is the sum of the runtime complexity of the network model’s forward propagation and backpropagation, which mainly depends on the number of layers of the network structure, the size of the convolutional kernel, and the number of input and output channels, which is closely related to the number of model trainable parameters. The experiments were conducted on a PC configured with AMD Ryzen 7-5800H @ 3.20 GHz and 16 GB RAM, and the average running times of 100 experiments with different sizes of sample data were recorded to represent the runtime complexity, as shown in Table 6.

In the experiments, the runtime complexity of the two Transformer deep learning architectures is O(n2) and the computational resources required are too large both in terms of the number of parameters and the runtime complexity. The runtime complexity of GoogLeNet, ResNet, and our proposal is O(n), but despite the simplicity of the GoogLeNet network structure with a low number of parameters and time complexity, its Trojan detection capability is limited compared to ResNet with a residual structure for more complex tasks. Although the network structure of the encoder for feature extraction in our framework uses a backbone network consistent with ResNet, it naturally leads to additional computational overhead and time due to the additional computational tasks involved in the training process such as data augmentation operations and sample pair generation. Although our proposal increases the runtime complexity marginally, it is still kept within acceptable limits. Therefore, when dealing with large-scale data or more complex tasks, our proposal can also show better performance in terms of scalability and computational efficiency.

Assessment of generalization capacity

Generalization capabilities as an important index to assess the quality of the model determines the reliability of the model in practical applications. In the HT detection task, the network model should not only perform well on the samples in the training data, due to the complicated size and function of the HT, so a network model with good generalization capabilities is still required to show good detection ability when facing HTs of unknown types and sizes.

As several previous metrics have shown that ResNet based on deep convolutional neural networks has shown competitive advantages in HT detection tasks, this paper also focuses on carrying out comparative experiments between our proposal and it in the generalization capability assessment. Figure 11 lists the detection rates of the ResNet residual network for nine different HT under supervised learning and our proposed contrastive learning framework to validate the generalization capabilities of the network model, where the network is trained using datasets of HT with the smallest and largest area T100 and T2100, respectively. As shown in Fig. 11, the training and testing use datasets with different sizes of Trojans, and the larger the difference in the area of the Trojans the lower the detection rate. Although the models trained by T100 and T2100 under the contrastive learning framework are less accurate than supervised learning on the test set of the corresponding trojan not reaching 100% with 98 and 99% respectively. However, the detection rate of HT on the test set of other types of Trojans does have a significant advantage, with the T100 small Trojan-trained model having up to 44% detection efficiency advantage in detecting large Trojans, and the T2100 large Trojan-trained model having up to 10% detection efficiency advantage in detecting small Trojans. This is due to the fact that ResNet’s supervised learning-based model overly relies on the labels of the training data may learn too many features related to specific variants of the training data rather than generic Trojan detection features, and thus the model does not generalize well to new Trojan variants. Whereas, the features learned by contrast learning do not rely on labeled supervised information, but are learned from a large number of generated contrast samples. As a result, unsupervised comparative learning is able to capture more general and robust feature representations that can be generalized to unseen hardware trojan variants and environmental conditions for detection tasks. The result represents that the same network model can return a stronger generalization capabilities at a very small.

sacrifice in the contrastive learning framework. Our proposed contrastive learning framework is more suitable to be applied in the HT detection task for detecting HT on unknown devices.

In HT detection, a large difference in the number of normal circuit samples and malicious circuit samples may cause the model to show bias in the training and testing phases which means that it is more inclined to predict the category with a higher number of samples and is weaker in recognizing a few categories. Therefore, in order to assess whether the detection performance and generalization capabilities of the model can remain stable and effective in the face of an imbalance of samples from different categories. In this paper, we conducted a comparison experiment for HT detection in this context. Our previous assessment of generalization capabilities revealed that a greater size discrepancy between the HT used for model training and the HT to be detected results in worse generalization. Therefore, we focus on modeling and detecting two types of Trojans: the largest, T2100, and the smallest, T100. As shown in Table 7, in the state of data imbalance, the accurate rate of both methods decreases to different degrees. Since the ResNet network over-adapts to a small number of samples in the training data, and the inability to generalize to new unseen samples may lead to the overfitting phenomenon, even though the model performs well on the training set, it has poor generalization capabilities on the test set. Whereas, in the case of imbalance in the number of positive and negative samples, contrast learning can effectively deal with the imbalance problem by generating more negative samples through data augmentation or deforming and expanding the existing positive samples and then combining the feature representations learned from the contrast loss function. Therefore, even in the case of large differences in the number of positive and negative samples, our proposal can still maintain high detection performance.

In HT detection, there are different types of noise, such as power supply noise, electromagnetic interference and so on, which may confuse the feature expression of positive and negative samples, thus affecting the performance of HT detection methods. Therefore, in order to evaluate whether the detection performance and generalization capabilities of the model can remain stable and effective in a noisy environment. In this paper, we conduct HT detection comparison experiments in this situation, and we also focus on modeling and detecting the largest T2100 and the smallest T100 Trojans. As shown in Table 8, the noise environment has a more significant effect on the efficiency of HT detection compared to data imbalance. ResNet relies on the learning of accurate features during the training process, while noise may make the feature boundary between normal and abnormal samples blurred, or even rely on these noisy data leading to a decrease in the ability to generalize on real data, thus affecting the performance of detecting HTs. Whereas, contrast learning can utilize a large number of contrast samples to learn more complex and discriminative features by comparing the feature representations learned by the loss function, which can resist the impact of noise on the data. Even if part of the data is disturbed by noise, the model is still able to learn discriminative feature representations from a large number of comparison samples. Therefore, our proposal maintains relatively higher detection performance even in noisy environments.

Conclusion

In hardware trojan detection, although deep convolutional neural networks based on supervised learning demonstrate good detection results, but they usually require a large amount of labeled data to train the model. In practice, obtaining sufficient amount and quality of labeled data is a difficult and expensive task, especially in high-risk environments like hardware security. This dependency severely limits the scalability and generalization capabilities of the model, making it difficult to effectively deal with emerging and unknown HT attacks. Therefore, this paper aims to address these challenges by introducing a contrastive learning framework based on SimCLR, which utilizes a comparative loss function that can be effectively trained with large-scale unlabeled data. This approach reduces dependence on labeled data and enhances the model’s detection performance and generalization capabilities in unsupervised or weakly supervised scenarios. The experimental results show that our proposed has a hardware trojan detection rate comparable to that of supervised classification models in unsupervised or weakly-supervised scenarios, and performs better detection capability when confronted with unknown HT in a device. We plan to extend it to larger scale designs in future work to validate the generalizability and effectiveness of the methodology. We believe that the method can still maintain its detection efficiency with the incorporation of larger scale designs and will be further optimized in future studies to suit the practical needs of larger designs.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Shakya, B., He, T. & Salmani, H. Benchmarking of hardware trojans and maliciously affected circuits. Journal of Hardware and Systems Security. 1(1): 85–102 (2017).

Mal-Sarkar, S., Karam, R. & Narasimhan, S. Design and validation for FPGA trust under hardware trojan attacks. IEEE Transactions on Multi-Scale Computing Systems. 2(3), 186–198 (2016).

Jin, Y., Kupp, N. & Makris, Y. Experiences in hardware trojan design and implementation. IEEE International Workshop on Hardware-Oriented Security and Trust. 2009, 50–57 (2009).

Lodhi, F. K., Hasan, S. R., Hasan, O. & Awwadl, F. Power profiling ofmicrocontroller’s instruction set for runtime hardware trojans detectionwithout golden circuit models. Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). 294–297 (2017).

Narasimhan, S., Yueh, W., Wang, X., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Bhunia, S. Improving IC security against Trojan attacks through integrationof security monitors. IEEE Des. Test Comput. 29(5), 37–46 (2012).

He, J., Guo, X., Ma, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, Y. & Jin, Y. Runtime trust evaluation and hardware trojan detection using on-chip EM sensors. 2020 57th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC). 1–6 (2020).

Bao, C., Forte, D. & Srivastava, A. Temperature tracking: Towardrobust run-time detection of hardware trojans. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 34(10), 1577–1585 (2015).

Forte, D., Bao, C. & Srivastava, A. Temperature tracking: An innovative run-time approach for hardware trojan detection. IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design (ICCAD). 2013, 532–539 (2013).

Ngo, X. T. et al. Robisson. Hardware trojan detection by delay and electromagnetic measurements. Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 782–787 (2015).

Zhang, X.& Tehranipoor, M. RON: An on-chip ring oscillator network for hardware trojan detection. 2011 Design, Automation & Test in Europe., 1–6 (2011).

Wang, L. W., Luo, H. & Yao, R. H. Hardware trojan detection method based on bypass analysis. Journal of South China University of Technology. 40(6), 6–10 (2012).

Wang, L. W., Jia, K. P. & Fang, W. X. Detection method of hardware trojan based on Mahalanobis distance. Microelectronics. 43(6) (2013).

Liu, Y. J., He, C. H. & Wang, L. W. Detection method of hardware trojan based on genetic algorithm. Microellectronics & Computer. 33(11), 74–77 (2016).

Yu, Y., Ni, J. & Au, M. H. Improved security of a dynamic remote data possession checking protocol for cloud storage. Expert Syst. Appl. 41(17), 7789–7796 (2014).

Yu, Y., Au, M. H. & Ateniese, G. Identity-based remote data integrity checking with perfect data privacy preserving for cloud storage. IEEE Trans on Information Forensics and Security. 12(4), 767–778 (2017).

Pirpilidis, F., Voyiatzis, A. G. & Pyrgas, L. An efficient reconfigurable ring oscillator for hardware trojan detection. Pan-Hellenic Conference on Informatics. 1–6 (2016).

Shende, R. & Ambawade, D. D. A side-channel based power analysis technique for hardware trojan detection using statistical learning approach. Thirteenth International Conference on Wireless and Optical Communications Networks (WOCN). 2016, 1–4 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Hardware trojan detection based on ELM neural network. First IEEE International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI). 2016, 400–403 (2016).

Adokshaja, B. L. & Saritha, S. J. Third party public auditing on cloud storage using the cryptographic algorithm. Third party public auditing on cloud storage using the cryptographic algorithm. 3635–3638 (2017).

Xue, L., Ni, J. B. & Li, Y. N. Provable data transfer from provable data possession and deletion in cloud storage. Computer Standards & Interfaces. 54(1), 46–54 (2017).

Hu, T., Wu, L., Zhang, X., Yin, Y. & Yang, Y. Hardware trojan Detection Combine with Machine Learning: an SVM-based Detection Approach. 2019 IEEE 13th International Conference on Anticounterfeiting, Security, and Identification (ASID). 202–206 (2019).

Wen, Y. & Yu, W. Combining thermal maps with inception neural networks for hardware trojan detection. IEEE Embed. Syst. Lett. 13(2), 45–48 (2021).

Sun, S., Zhang, H. & Cui, X. Electromagnetic side-channel hardware trojan detection based on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 69(3), 1742–1746 (2022).

Hassan, R., Meng, X. & Basu, K. Circuit topology-aware vaccination-based hardware trojan detection. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 42(9), 2852–2862 (2023).

Tan, Z., Chen, J., Kang, Q., Zhou, M. C. & Sedraoui, K. Dynamic Embedding Projection-Gated Convolutional Neural Networks for Text Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks Learning Systems 33(3), 973–982 (2022).

Xu, Y., Yu, Z., Cao, W. & Chen, C. L. P. Adaptive Dense Ensemble Model for Text Classification. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics. 52(8), 7513–7526 (2022).

Lu, Z., Liang, S., Yang, Q. & Du, B. Evolving Block-Based Convolutional Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience Remote Sensing. 60 (2022).

Chang, Y. L. et al. Consolidated Convolutional Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Classification. Remote Sensing. 14(7), (2022).

Huang, Y. & Hu, H. A Parallel Architecture of Age Adversarial Convolutional Neural Network for Cross-Age Face Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Circuits Systems for Video Technology. 31(1), 148–159 (2021).

Gao, G., Yu, Y., Yang, J., Qi, G. J. & Yang, M. Hierarchical Deep CNN Feature Set-Based Representation Learning for Robust Cross-Resolution Face Recognition. IEEE Transactions on Circuits Systems for Video Technology. 32(5), 2550–2560 (2022).

Wang, Y. F., Wan, S. P., Zhang, S. J. & Yu, J. S. Speaker Recognition of Fiber-Optic External Fabry-Perot Interferometric Microphone Based on Deep Learning. IEEE Sens. J. 22(13), 12906–12912 (2022).

Jaber, H. Q. & Abdulbaqi, H. A. Real time Arabic speech recognition based on convolution neural network. Journal of Information Optimization Sciences. 42(7), 1657–1663 (2021).

Bachman, P., Hjelm, R. D. & Buchwalter, W. Learning representations by maximizing mutual information across views. International Conference on Machine Learning. 15509–15519 (2019).

Hénaff, O. J., Razavi, A.., Doersch, C., Eslami, S. & Oord, A.v. d. Data-efficient image recognition with contrastive predictivecoding. International Conference on Machine Learning (2019).

Wu, Z., Xiong, Y., Yu, S. X. & Lin, D. Unsupervised featurelearning via non-parametric instance discrimination. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018, 3733–3742 (2018).

Tian, Y., Krishnan, sD. & Isola, P. Contrastive multiview coding. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. (2019).

He, K., Fan, H., Wu, Y., Xie, S. & Girshick, R. Momentumcontrast for unsupervised visual representation learning. 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2020).

Misra, I. & Laurens, V. D. M. Self-supervised learn-ing of pretext-invariant representations. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2019).

Chen, T., Kornblith, S., Norouzi, M. & Hinton, G. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations. International Conference on Machine Learning (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 61471158).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zijing Jiang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. Qun Ding: Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Z., Ding, Q. A framework for hardware trojan detection based on contrastive learning. Sci Rep 14, 30847 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81473-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81473-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A low-power FSM-based hardware intrusion detection system with lightweight decoy logic for secure SoC architectures

International Journal of Information Technology (2025)