Abstract

The NAC family is among the most extensive sets of plant-exclusive transcription factors (TFs), which are crucial for various plant development and stress response processes. Although a growing number of studies have been carried out on the NAC family in different species, it has not been characterized in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. To thoroughly understand the effects of methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and sodium chloride (NaCl) inductions on NAC TFs and investigate the underlying regulatory mechanism of NAC TFs in response to MeJA and NaCl on the biosynthesis of metabolites, we used transcriptome sequencing combined with qRT‒PCR to explore differential gene expression. Comparative transcriptomic profiling by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) revealed differentially expressed NAC TFs between MeJA/CK (Mock Control) and NaCl/CK. KEGG pathway analysis revealed that NAC TFs involved in starch and sucrose, carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, as well as terpenoid, polyketide, and flavonoid pathways, can regulate the MeJA- and NaCl-induced responses of G. uralensis. This research lays the groundwork for a thorough comprehension of the regulatory mechanism of NAC TFs in response to MeJA and NaCl induction and their involvement in the accumulation of secondary metabolites, which can provide a scientific basis for the cultivation of high-quality varieties of G. uralensis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glycyrrhiza uralensis fisch. (licorice) a highly valuable medicinal plant worldwide and is commercially valued for its pharmaceutical, natural sweetener, flavor-enhancing, and cosmaceutical properties1. It has been included in the official pharmacopeias of the Chinese, European, and United States. The primary bioactive compounds found in G. uralensis, namely, triterpenoids and flavonoids, possess a spectrum of therapeutic attributes, which include detoxification2, anti-inflammatory effects3, antitumor capabilities4, and the potential to protect the liver5.

The regulation of gene transcription is a fundamental process that is crucial for plants to develop resistance against harmful environmental stressors. Transcription factors (TFs) can induce or repress the transcription of multiple target genes by attaching to cis-regulatory elements within their promoter sequences6. Several TFs have been reported to contribute to the plant response to abiotic stress7. The NAC TF family is among the most extensive plant-specific TF families, and its regulatory networks mediate complex signaling8 as well as transcriptional reprogramming9. The distinctive structural and functional attributes of NAC TFs include a highly invariant DNA-binding motif situated at the N-terminus and a dynamic interaction involving the C-terminal domain with various proteins10. Furthermore, the NAC domain governs protein binding, influencing the role of the NAC protein, which is crucial in plant‒pathogen engagement and stress tolerance11.

NAC TFs have been shown to participate in plant growth and maturation, including cell proliferation, secondary cell wall development, shoot apex meristem formation, floral structure and fruit maturation, leaf deterioration, and abiotic stress response processes. As a complex and plant-specific group, NAC TFs are distributed across various species. Certain maize strains presented variations in the NAC78 promoter sequence, which was linked to the level of NAC78 expression in transformed endosperm cells. The expression of iron transporters was elevated in these cells, indicating a potential increase in iron being transported into the kernel, which could contribute to mitigating iron deficiency12. Moreover, the expression of the NAC TF JUNGBRUNNEN1 (JUB1) is increased by the drought tolerance of various abiotic stresses in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and the expression of JUB1 (SlJUB1) positively regulates the tolerance of tomato plants to drought13. In contrast to the extensive studies on the biosynthetic route of the active components within G. uralensis, the exploration of key TFs that control the biosynthesis of the active ingredients in G. uralensis is still limited. Additionally, there have been no reports of the participation of NAC TFs in the regulatory processes of MeJA and NaCl induction in G. uralensis.

In this study, NAC TFs that respond to MeJA and NaCl inductions in G. uralensis were screened, and their expression patterns were verified. These results establish a basis for studying the molecular mechanism of MeJA- and NaCl-mediated NAC TFs that regulate the synthesis of secondary metabolites in G. uralensis and establish a theoretical basis for breeding high-quality germplasm resources of G. uralensis.

Results

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of G. uralensis to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

The resulting sets of CK, MeJA, and NaCl samples yielded 240.05 to 253.16 million and 212.67 to 228.29 million raw and clean reads per library, respectively. The Q30%, which represents sequences with a sequencing error rate less than 0.1%14, was greater than 92% for each library, and the average GC content for all the libraries was approximately 45%. Moreover, the percentage of clean reads that aligned to the reference genome varied from 86.36 to 90.39% for each library (Tables S1,S2). In summary, the data indicated that the RNA-seq results were of high quality and suitable for additional analysis.

DESeq was ultilized to estimate the fold changes and dispersion in RNA-seq data for the identification of DEGs. There were 2,078 and 1,663 DEGs detected in the MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK comparisons, respectively, which comprised 962 and 630 upregulated genes, as well as 1,116 and 1,033 downregulated genes. In the two comparisons, 508 DEGs (comprising 141 upregulated and 337 downregulated) were common across the three treatments (Fig. 1; Table S3).

DEGs in G. uralensis transcriptomes. (A) Venn diagram showing the total DEGs (a), downregulated DEGs (b), and upregulated DEGs (c) in MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK. (B) Expression levels of the TFs in each group. (C) Volcano map analysis of DEGs in the MeJA/CK group. (D) Volcano map analysis of DEGs in the NaCl/CK group, with red, green, and gray points indicating upregulated, downregulated, and unaltered genes, respectively.

Identification of TFs in G. uralensis

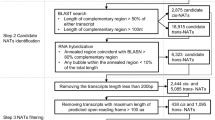

The modulation of gene expression by TFs is a widespread and crucial aspect of cellular responses to both biotic and abiotic stressors. To gain deeper insight into the molecular processes involved in the response to inductions in G. uralensis, the TF families were categorized on the basis of the plant transcription factor database (version 5.0)15. Up to 11,967 of the detected unigenes were assigned to 58 TF families, with bHLH, NAC, MYB, B3 and WRKY ranking as the five most prevalent TF families (Fig. 2A). Among these members, NAC TFs were the second most abundant class of TFs with 842 genes, ranking only after the bHLH TFs in terms of gene numbers. The bHLH TF in G. uralensis has already been reported to positively regulate the biosynthesis of soyasaponins16. In addition, the NAC family TFs were reported to participate in abiotic stress tolerance17, and to regulate the expression of multiple key genes involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in plants18. Interestingly, the results showed a high NAC-TF number in mock control (CK) compared to treatments (NaCl or MeJA) (Fig. 2B). The reduction in the number of TFs after MeJA and NaCl treatments may be involved in negative regulatory mechanism. The expression and activity of TFs are influenced by complex feedback regulatory mechanisms. Specific treatments may trigger negative feedbacks mechanism that inhibits the expression of some TFs19,20.Thus, it can be inferred that the NAC TFs were one of the vital players in MeJA- and NaCl-induced G. uralensis responses.

MeJA- and NaCl-responsive NAC TFs in the roots of G. uralensis

Cluster analysis was employed to identify the transcriptional profiles of the 842 NAC TFs in response to MeJA and NaCl treatments. These TFs were categorized into three vertical clusters on the basis of tissue variation and further divided into four horizontal clusters on the basis of their mRNA levels. Cluster 1 presented greater expression in response to NaCl induction than in CK or MeJA induction; TFs in cluster 2 were downregulated in expression after MEJA induction, whereas TFs in cluster 3 were upregulated in expression following MEJA induction. In addition, TFs in cluster 4 were highly expressed in the CK treatment than in the MeJA and NaCl treatments. The TFs in clusters 1 and 2 were clustered together, indicating that the TFs in the two clusters presented similar expression patterns in response to NaCl induction (Fig. 3A and B, Table S4). Among these genes, a total of 16 NAC TFs showed consistent expression trends in the MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK comparison groups (Fig. 3C).

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the NAC TFs

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were employed to illustrate the biological functions of the NAC TFs. The top 20 enriched functional categories based on the GO terms were depicted in (Fig. 4). The significantly enriched GO terms across all the samples predominantly represented biological processes and molecular functions. In G. uralensis roots, the gene expression and regulation of biological processes were most significantly enriched after MeJA induction (Table S5), whereas organic cyclic compound metabolic processes was predominant after NaCl induction (Table S6). Moreover, those related to metabolic and organic substance biosynthetic processes constituted a great proportion of the total organic cyclic compound biosynthetic processes. In the molecular function category, many NAC TFs related to coenzyme and cofactor binding were enriched. In the cellular component category, “cell wall” and “external encapsulating structure organization” were the most highly represented terms in both MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK. Moreover, NAC TFs involved in oxidoreductase activity were enriched in the NaCl/CK group (Fig. 4).

KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the majority of metabolic pathways were significantly enriched in the MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK comparisons (Fig. 5). Apart from pathways involving in starch and sucrose metabolism, the remaining enriched pathways in both MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK primarily pertained to amino acid and sugar metabolism, encompassing trems such as metabolism of cyanoamino acids; glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism; glycolysis and gluconeogenesis; and the interconversion of pentoses and glucuronates. Pathways responsible for the synthesis of key metabolites were notably enriched, with the top three being starch and sucrose metabolism; primary metabolic pathways (including carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism); and secondary metabolite biosynthesis (encompassing amino acid, terpenoid and polyketide, and carbohydrate metabolism). Moreover, isoflavonoid biosynthesis was also highlighted as an enriched pathway with a substantial enrichment factor (Tables S7-S8). Notably, the enrichment of terpenoid and polyketide metabolism was unique to the MeJA/CK comparison (Table S7).

KEGG enrichment analysis of NAC TFs in G. uralensis. (A) MeJA/CK. (B) NaCl/CK. The details of the KEGG pathway were from www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html.

Expression patterns of NAC TFs in G. uralensis after MeJA and NaCl inductions

To ascertain the concordance between the expression profiles of DEGs and RNA-seq data, we analyzed the expression of 16 differential NAC TFs (Fig. 3C) in the MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK comparison groups by qRT‒PCR. The results showed that the expression levels of NAC2, NAC10, NAC12, NAC14, and NAC16 were increased with MeJA and NaCl inductions compared with the control treatment, while the expression levels of NAC1, NAC3-NAC9, NAC11, NAC13, and NAC15 were decreased in response to MeJA and NaCl inductions (Fig. 6). The transcriptome data showed a high degree of concordance with the expression trends of the TFs, confirming the reliability of the gene expression profiles identified through RNA-seq. These results indicated that the 16 NAC TFs may be involved in the response to MeJA and NaCl inductions in G. uralensis.

Discussion

As a widely used medicinal plant with rich medicinal functions, G. uralensis is extensively distributed in arid and semiarid regions of northern and northwestern China, and has the functions of drought resistance and salt tolerance21. Owing to global warming and the reduction in suitable agricultural land, there is an urgent need to breed resistant varieties of G. uralensis and improve the superior traits and qualities of G. uralensis22. Therefore, through the analysis of NAC family TFs in G. uralensis, this study provides data for exploring the involvement of NAC TF family members in the metabolic regulation of bioactive constituents and offers a reference for the breeding of superior varieties of G. uralensis.

Abiotic stress (NaCl induction) and hormone (MeJA induction) play vital roles in the growth and development of plants, which can induce direct defense substances, regulate gene expression in plants, and increase the accumulation of secondary metabolites to resist stress23. MeJA induces the expression of TFs in tea leaves, and their expression patterns are positively or negatively correlated with the expression of flavonoid biosynthetic genes, thereby regulating the biosynthesis of flavonoids in tea24. Additionally, it has been reported that the TF PgbHLH28 is a key regulatory factor in the MeJA-induced accumulation of platycodon saponins25. TFs can act as activators or repressors to regulate the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites under salt stress26. Treatment with NaCl can induce defense responses such as oxidative stress in plants and plays a crucial role in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites27. Interestingly, exogenous application of MeJA may enhance plant tolerance to salt stress, and NaCl stress can also induce the biosynthesis of endogenous MeJA28. Exogenous MeJA can enhance the salt tolerance of perennial ryegrass, and the mechanism may be related to the upregulation of the antioxidant defense system29. The NAC TFs in this study play roles in the MeJA and NaCl stress responses, which is similar to the simultaneous response of TF SIWRKY81 in tomato to the inductions of NaCl and jasmonic acid30. Therefore, we speculate that MeJA and NaCl induce the expression of NAC TFs, thereby regulating the accumulation of active components in G. uralensis.

Transcriptomic data directly provides information on the expression levels of genes under specific conditions, which is crucial for studying gene function and regulatory mechanisms31. The genomic data of G. uralensis offers sequence information of genes, while transcriptomic data can be annotated for function by comparison with known databases to understand the biological functions of genes and the relative metabolic pathways. Plants induce or suppress TFs in response to stresses, which aids in their adaptation to the environment. Additionally, TFs coordinate the expression of genes involved in the biosynthetic pathways of secondary metabolism, playing an important role in the synthesis of various components in medicinal plants32. Licorice is one of the most popular traditional herbs, used medicinally with its dried roots and rhizomes for the treatment of respiratory diseases, inflammations, and cancer. The root or rhizome of licorice is rich in important active secondary metabolites such as flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins33. Thus, root samples were collected for RNA isolation and transcriptome analysis in this study.

Our GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of the NAC TFs revealed that the NACs were involved in biological processes or molecular functions, such as the metabolism and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites; starch, sucrose, carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism; and terpenoid, polyketide, and flavonoid metabolism pathways. These NAC TFs might play significant roles in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in G. uralensis in response to MeJA and NaCl inductions. The NAC TFs can increase the resistance of plants and are involved in regulating the biosynthesis of many secondary metabolites34,35,36. According to previous researches, interactions between NAC TFs with other elements or genes in Arabidopsis thaliana may contribute to NAC-mediated regulation of expression37 or the maturation of root tissues38. Moreover, NAC TFs can interact with other TFs to establish a complex regulatory network, thus precisely regulating leaf senescence39. The NAC gene (TaNAC071-A) in wheat is closely related to drought tolerance40. Other studies have revealed that the expression of the NAC family TF NAC3 in potato is induced by various stresses and can inhibit ABA signal transduction41. However, in medicinal plants, only a few scholars have documented the application of transcriptomics technology to investigate the effects of the PgNAC72 TF on mediating the molecular mechanism of ginsenoside synthesis and accumulation under methyl jasmonate treatment through the upregulation of damalenediol synthase18. In this study, NAC TFs associated with oxidoreductase activity were enriched in the NaCl/CK group, which indicated that NaCl induction may lead to cellular ion toxicity and that NaCl-induced G. uralensis likely evolved an effective protective mechanism through the generation of a sequence of enzymes to maintain osmotic homeostasis and decrease the risk of oxidative stress42.

The NAC family is among the most extensive groups of TFs exclusive to the plant kingdom, with a wide range of roles in plant growth, maturation, and the ability to cope with both abiotic or biotic stresses43. Our results go beyond previous studies that focused mainly on one abiotic stress and enriched the exploration of NAC TFs of G. uralensis, establishing a foundation for further studies on the molecular mechanism and function of NAC TFs in response to MeJA and NaCl induction. Moreover, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the functions of the NAC TFs in G. uralensis and the transcriptional regulation of G. uralensis, as well as the use of the NAC family TFs to improve the stress resistance of G. uralensis.

In conclusion, to gain more insight into the regulatory processes of the NAC network under MeJA and NaCl stimulations, a comparative transcriptional strategy (integrating RNA sequencing with qRT‒PCR) was utilized to examine the regulatory pathways of NAC TFs involved in metabolite biosynthesis under MeJA and NaCl treatments in G. uralensis, which is highly valuable for predicting the functions of NAC proteins within the regulatory network. These findings offer a valuable framework for elucidating the functional roles of NAC TFs in G. uralensis. Moreover, the application and enhancement of current NAC TFs for plant genetic resource innovation and breeding are highly relevant and useful for future studies.

Methods

Deep transcriptome sequencing of G. uralensis seedlings after MeJA and NaCl induction

One-month-old G. uralensis seedlings were collected from Minqin City, Gansu Province of China. The seedlings were grown in a light incubator at 25 °C with a light/dark cycle of 16/8 hours and a humidity of 30–35%. After 30 days of growth, the plants were subjected to treatments of CK, NaCl, and MeJA. Root samples were collected after the different induction treatments, with three biological replicates for each treatment. The samples were then flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until transcriptomic examination.

RNA sequencing library preparation and transcriptome sequencing

RNA was isolated from the roots of G. uralensis in each treatment group and the control group. For each sample, 1 µg of RNA was employed as the starting material for RNA preparation via the TRIzol total RNA isolation reagent (Beijing LABLEAD, Inc.). Libraries for sequencing were constructed with the NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality and quantity were checked on a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA), and cDNA libraries were prepared following the Illumina protocol. Deep transcriptome sequencing of G. uralensis with a depth greater than 6 Gb, and libraries were conducted on all groups to ensure comprehensive gene coverage. The raw reads in fastq format underwent initial filtering via custom Perl scripts. Clean reads were obtained by the exclusion of reads with adapters, those with poly-N sequences, and reads of poor quality from the initial dataset. Cufflinks v2.1.1 software was used with the reference annotation-based transcript (RABT) assembly technique to compile and distinguish known and novel transcripts from the outcomes of the TopHat alignment. HTSeq v0.9.1 was employed to align the reads to each gene. The FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped fragments) values for the genes were subsequently determined by considering the gene length and the number of reads that aligned to it.

Differential expression analysis via RNA-seq

The analysis of differential gene expression between the treatments and the control was conducted via the DESeq R package (version 1.18.0). DESeq offers statistical methodologies for the identification of differential expression in digital gene expression datasets, utilizing a model that relies on the negative binomial distribution. The P values obtained from this analysis were then corrected via the Benjamini and Hochberg method to manage the false discovery rate. Genes were classified as differentially expressed if they had an adjusted P value below 0.05 as indicated by DESeq. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were clustered hierarchically via Gene Cluster 3.0, and the results were visualized via Java Treeview44. Overlaps between DEGs and NACs were constructed via VENNY 2.1 software (available at http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html).

GO (gene ontology) and KEGG annotation and functional categorization of NAC TFs

Enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology (GO) terms was conducted via the GOseq R package, which addresses potential biases related to gene length. GO categories with adjusted P values less than 0.05 were regarded as significantly enriched in the TFs. KEGG serves as a database for comprehending the advanced functionalities and applications of biological entities, including cells, organisms, and ecosystems, derived from molecular data, particularly extensive molecular datasets produced by genomic sequencing and other high-throughput experimental methods (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). We employed the KOBAS tool to analyze the significant enrichment of TFs in KEGG pathways.

qRT‒PCR analysis

Sixteen NAC TFs that differentially expressed in both MeJA/CK and NaCl/CK were chosen for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‒PCR) analysis. The PrimeScript Reagent Kit from TaKaRa (Dalian, China) was used to generate cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA. qRT‒PCR was conducted via TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Biotechnology Inc., Dalian, China) on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. The primers used for amplifying the unigenes and the reference gene actin are detailed in Table S9. The procedure was carried out with three biological and technical replicates, with actin used as the housekeeping gene. The expression levels of the unigenes were determined via the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Song, W. et al. Biosynthesis-based quantitative analysis of 151 secondary metabolites of licorice to differentiate medicinal glycyrrhiza species and their hybrids. Anal. Chem. 89, 3146–3153. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04919 (2017).

Li, T. et al. Spectrum-effect relationships of flavonoids in glycyrrhiza uralensis fisch. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 8838290. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8838290 (2020).

Yin, L. et al. Chemical profile and anti-inflammatory activity of total flavonoids from glycyrrhiza uralensis fisch. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 17, 726–734 (2018).

Ayeka, P. A., Bian, Y., Githaiga, P. M. & Zhao, Y. The immunomodulatory activities of licorice polysaccharides (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) In CT 26 tumor-bearing mice. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 17, 536. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-017-2030-7 (2017).

Kuang, Y. et al. Screening of hepatoprotective compounds from licorice against carbon tetrachloride and acetaminophen induced HepG2 cells injury. Phytomedicine 34, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2017.08.005 (2017).

An, J. P. et al. An apple NAC transcription factor negatively regulates cold tolerance via CBF-dependent pathway. J. Plant. Physiol. 221, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2017.12.009 (2018).

Li, X. D. et al. Overexpression of a novel NAC-type tomato transcription factor, SlNAM1, enhances the chilling stress tolerance of transgenic tobacco. J. Plant. Physiol. 204, 54–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2016.06.024 (2016).

Shao, H., Wang, H. & Tang, X. NAC transcription factors in plant multiple abiotic stress responses: progress and prospects. Front. Plant. Sci. 6, 902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00902 (2015).

Jin, J. et al. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1040–D1045. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw982 (2017).

Olsen, A. N., Ernst, H. A., Leggio, L. L. & Skriver, K. NAC transcription factors: structurally distinct, functionally diverse. Trends Plant. Sci. 10, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.010 (2005).

Puranik, S., Sahu, P. P., Srivastava, P. S. & Prasad, M. NAC proteins: regulation and role in stress tolerance. Trends Plant. Sci. 17, 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2012.02.004 (2012).

Yan, P. et al. Biofortification of iron content by regulating a NAC transcription factor in maize. Science 382, 1159–1165. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf3256 (2023).

Thirumalaikumar, V. P. et al. NAC transcription factor JUNGBRUNNEN1 enhances drought tolerance in tomato. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 16, 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.12776 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. CoolMPS: evaluation of antibody labeling based massively parallel non-coding RNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, e10. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa1122 (2021).

Chang, W. C. & Chow, C. N. Database for plant transcription factor binding sites. Methods Mol. Biol. 2594, 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2815-7_13 (2023).

Tamura, K. et al. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor GubHLH3 positively regulates soyasaponin biosynthetic genes in Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 59, 778–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcy046 (2018).

Yu, X. et al. Transcription factor NAC78 cooperates with NAC78 interacting protein 6 to confer drought tolerance in rice. Plant. Physiol. 196, 1642–1658. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiae395 (2024).

Jiang, T. et al. Transcription factor PgNAC72 activates dammarenediol synthase expression to promote ginseng saponin biosynthesis. Plant. Physiol. 195, 2952–2969. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiae202 (2024).

Wang, X. Y. et al. CwJAZ4/9 negatively regulates jasmonate-mediated biosynthesis of terpenoids through interacting with CwMYC2 and confers salt tolerance in Curcuma Wenyujin. Plant. Cell. Environ. 47, 3090–3110. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.14930 (2024).

Jiang, L. et al. The OsGAPC1-OsSGL module negatively regulates salt tolerance by mediating abscisic acid biosynthesis in rice. New. Phytol. 244, 825–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.20061 (2024).

Dang, H. et al. Population Evolution, genetic diversity and structure of the Medicinal Legume, Glycyrrhiza uralensis and the effects of geographical distribution on leaves nutrient elements and photosynthesis. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 708709. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.708709 (2021).

Yan, B. et al. A review on the plant resources of important medicinal licorice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 301, 115823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115823 (2023).

Upadhyay, R. K., Edelman, M., Mattoo, A. K. & Identification Phylogeny, and comparative expression of the Lipoxygenase Gene Family of the aquatic duckweed, Spirodela polyrhiza, during growth and in response to Methyl Jasmonate and Salt. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249527 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Diverse roles of MYB transcription factors in regulating secondary metabolite biosynthesis, shoot development, and stress responses in tea plants (Camellia sinensis). Plant. J. 110, 1144–1165. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.15729 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. RNA sequencing analysis reveals PgbHLH28 as the key regulator in response to methyl jasmonate-induced saponin accumulation in platycodon grandiflorus. Hortic. Res. 11, uhae058. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhae058 (2024).

Zhao, K., Lan, Y., Shi, Y., Duan, C. & Yu, K. Metabolite and transcriptome analyses reveal the effects of salinity stress on the biosynthesis of proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins in grape suspension cells. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1351008. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1351008 (2024).

Khalofah, A., Bamatov, I. & Zargar, M. Interaction of melatonin and H(2)S mitigates NaCl toxicity summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) through modulation of biosynthesis of secondary metabolites and physio-biochemical attributes. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. 31, 47757–47770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-34356-w (2024).

Lv, B. et al. SmJAZs-SmbHLH37/SmERF73-SmSAP4 module mediates jasmonic acid signaling to balance biosynthesis of medicinal metabolites and salt tolerance in Salvia miltiorrhiza. New. Phytol. 244, 1450–1466. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.20110 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Methyl jasmonate enhances salt stress tolerance associated with antioxidant and cytokinin alteration in perennial ryegrass. Grass Res. 3 https://doi.org/10.48130/GR-2023-0006 (2023).

Shang, C. et al. SlWRKY81 regulates Spd synthesis and na(+)/K(+) homeostasis through interaction with SlJAZ1 mediated JA pathway to improve tomato saline-alkali resistance. Plant. J. 118, 1774–1792. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.16709 (2024).

Guo, J., Huang, Z., Sun, J., Cui, X. & Liu, Y. Research progress and future development trends in medicinal plant transcriptomics. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 691838. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.691838 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. The central role of transcription factors in bridging biotic and abiotic stress responses for plants’ resilience. New. Crops 1, 100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ncrops.2023.11.003 (2024).

Cheng, M. et al. Recent advances in chemical analysis of licorice (Gan-Cao). Fitoterapia 149, 104803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2020.104803 (2021).

Diao, P. et al. The role of NAC transcription factor in plant cold response. Plant. Signal. Behav. 15, 1785668. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2020.1785668 (2020).

Liu, G. S., Li, H. L., Grierson, D. & Fu, D. Q. NAC Transcription factor family regulation of fruit ripening and quality: a review. Cells 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11030525 (2022).

Xu, B. et al. Contribution of NAC transcription factors to plant adaptation to land. Science 343, 1505–1508. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1248417 (2014).

He, L., Xu, J., Wang, Y. & Yang, K. Transcription factor ANAC074 binds to NRS1, NRS2, or MybSt1 element in Addition to the NACRS to regulate Gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19103271 (2018).

Xie, C. et al. NAC1 regulates root ground tissue maturation by coordinating with the SCR/SHR-CYCD6;1 module in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 16, 709–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2023.02.006 (2023).

Kim, H. J., Nam, H. G. & Lim, P. O. Regulatory network of NAC transcription factors in leaf senescence. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 33, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2016.06.002 (2016).

Mao, H. et al. Variation in cis-regulation of a NAC transcription factor contributes to drought tolerance in wheat. Mol. Plant. 15, 276–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2021.11.007 (2022).

Meng, X. et al. The unique sweet potato NAC transcription factor IbNAC3 modulates combined salt and drought stresses. Plant. Physiol. 191, 747–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac508 (2023).

Yang, Y. & Guo, Y. Unraveling salt stress signaling in plants. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 60, 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12689 (2018).

Han, K., Zhao, Y., Sun, Y. & Li, Y. NACs, generalist in plant life. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 21, 2433–2457. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.14161 (2023).

Li, J. et al. DNA repair genes are associated with tumor tissue differentiation and immune environment in lung adenocarcinoma: a bioinformatics analysis based on big data. J. Thorac. Dis. 13, 4464–4475. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-949 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100309) and Candidates for the 2024-2026 Youth Talent Recruitment Program of Beijing City University (TJ202403). We thank Kanehisa Laboratories for copyright permission of KEGG (www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuan Li: Study design, methodology, writing—original draft. Yue Shi: Experimentation and formal analysis. Zidong Zhu: Formal analysis and visualization. Xiao Chen: Visualization and supervision. Kuangwei Cao: Supervision. Jiatong Li: Resources. Chunsheng Liu: Project administration and conceptualization. Da Li: Validation, supervision, and visualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Shi, Y., Zhu, Z. et al. Transcriptome‑wide excavation and expression pattern analysis of the NAC transcription factors in methyl jasmonate- and sodium chloride-induced Glycyrrhiza uralensis. Sci Rep 15, 6867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82151-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82151-x