Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), crucial mediators in cell-to-cell communication, are implicated in both homeostatic and pathological processes. Their detectability in easily accessible peripheral fluids like saliva positions them as promising candidates for non-invasive biomarker discovery. However, the lack of standardized methods for salivary EVs isolation greatly limits our ability to study them. Therefore, we rigorously compared salivary EVs isolated using two scalable techniques—co-precipitation and immuno-affinity—against the long-established but labor-intensive ultracentrifugation method. Employing Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM), Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis, Western blots (WB), and proteomics, we identified significant method-dependent variances in the size, concentration, and protein content of EVs. Importantly, our study uniquely demonstrates the ability of EV isolation to detect specific biomarkers that remain undetected in whole saliva by WB. RT-qPCR analysis targeting six miRNAs confirmed a consistent enrichment of these miRNAs in EV-derived cargo across all three isolation methods. We also found that pre-filtering saliva samples with 0.22 or 0.45 µm pores adversely affects subsequent analyses. Our findings highlight the untapped potential of salivary EVs in diagnostics and advocate for the co-precipitation method as an efficient, cost-effective, and clinically relevant approach for small-volume saliva samples. This work not only sheds light on a neglected source of EVs but also paves the way for their application in routine clinical diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, the exploration of extracellular vesicles (EVs) has ignited a surge of interest among researchers, unveiling a complex network of intercellular communication mechanisms. These small, membrane-bound entities have emerged as pivotal players in various physiological processes (both healthy and pathological), orchestrating a symphony of molecular interactions between cells1.

EVs are nanometric particles released by all cell types across diverse tissues and can be found abundantly in various body fluids, including blood, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), milk and saliva2,3,4,5,6. Their nanometric size range and lipid bilayer membrane structure are distinctive features that discriminate them from other soluble extracellular factors, rendering them particularly adept at traversing biological barriers and ensuring efficient intercellular communication1. A key aspect of EVs lies in their heterogeneity, which encompasses a wide array of subtypes, each characterized by specific biogenesis pathways and molecular cargo and are classified in three main groups: exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies1,7,8,9. These distinct origins confer unique biomolecular compositions, making EVs versatile mediators of diverse biological signals. Moreover, the features of this molecular cargo reflect the physiological and pathological state of the parent cell, underscoring the diagnostic and prognostic potential of EVs in various diseases10.

Most studies on EVs in biofluids focus on blood, urine, milk, and CSF. However, these biofluids have limitations for diagnostics, such as invasiveness, the need for trained personnel, infection risk, dilution effects (especially in urine), or small volumes (CSF) that limit testing and repeated sampling. In contrast, saliva offers a valuable alternative due to its non-invasiveness, ease of collection, and minimal requirements for expertise or equipment. Its dynamic composition reflects both local and systemic health, making it a useful proxy for assessing various pathologies11. Saliva contains biomarkers commonly measured in blood, showing good correlation between the two12, making it ideal for developing Point Of Care tests and reducing the need for costly laboratory testings. This potential was illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, where salivary auto-tests like EasyCOV® enabled low-cost, widespread testing13. However, contaminants, bacteria, and inhibitors in saliva present challenges, possibly explaining why it is less studied than other biofluids14.

EVs have been identified in saliva6,15 and could help overcome these limitations, unlocking the full diagnostic potential of this biofluid. Therefore, it is crucial to develop and standardize EV isolation methods specifically for salivary samples in diagnostic applications.

When comparing EV isolation methods, key differences emerge between techniques that broadly isolate EVs and those targeting specific subpopulations, such as tetraspanin-expressing EVs. Differential ultracentrifugation (UC), the current gold standard for isolating EVs16, separates particles based on their size and density through a series of centrifugation steps. This method effectively processes large sample volumes at a moderate cost while achieving purity levels suitable for downstream applications. However, it is time-consuming, requires expensive high-speed centrifuge equipment, does not allow a large number of samples to be processed in parallel and can carry non-EV contaminants like lipoproteins of similar density, limiting its clinical applicability. UC is ideal for general EV studies but lacks specificity. In contrast, polymer-based precipitation using polyethylene glycol (PEG), a hydrophilic volume-excluding polymer, has emerged as an alternative, enabling EV isolation in a shorter time with low-speed centrifugation17. This method is suitable for high-throughput studies across various human biofluids due to its lower cost and higher sample processing capability18,19,20. However, PEG-based methods often result in lower purity, as they can co-precipitate non-EV particles regardless of their densities. Immunoaffinity isolation, relying on the interaction between EV surface proteins and antibodies against tetraspanins like CD9, CD63, and CD81, specifically targets a subpopulation of EVs. This method provides high purity and is requested for studies focusing on specific EV functions or cellular origins, with the added benefits of requiring small sample volumes and offering faster processing21. However, it has trade-offs, including lower yield, higher costs, and the selective isolation of marker-specific vesicles that may not represent all EVs in the sample. These differences underscore the critical balance between yield, purity, and specificity in EV research. While UC and PEG methods are suited for broader EV analyses, immunoaffinity techniques are more relevant for studies on specific EV subpopulations, particularly in clinical applications where precision and compliance are essential.

To date, no direct comparison in saliva has been done to extensively show how these three different isolation methods influence the isolation results of salivary EVs regarding both their protein and nucleic acid cargos.

Published protocols from researchers and/or manufacturers instructions often mention the use of filtration in order to improve EVs recovery22,23. However, the assumed efficiency of this additional step has never been properly assessed and it remains unclear if this step is useful or, on the contrary, detrimental in terms of the molecular content of the EV.

In this study, we compared three methods relying on very different mechanisms to isolate EVs from human saliva, namely ultracentrifugation, co-precipitation and immuno-affinity. We propose a comprehensive analysis regarding the characterization of EVs, their protein and miRNA cargos. We also assessed the usefulness of adding a filtration step on protein and miRNA recovery for each method.

Results

Workflow for EV isolation by ultracentrifugation (UC), co-precipitation (Q) and immuno-affinity (M)

EVs were isolated from the volunteers’ saliva by three different isolation methods (Table 1). We compared a co-precipitation-based method (Qiagen) and an immuno-affinity based method (Miltenyi) with the differential ultracentrifugation technique, the latter being currently considered as the gold standard for EV isolation (see24 for review on these different techniques). An overview of the experimental workflow for saliva collection, processing and EVs isolation is depicted in Fig. 1 (see material and methods for detailed procedure). Once isolated, we assessed the characteristics of saliva derived EVs for each isolation method in parallel, namely EV UC, EV Q and EV M (for ultracentrifugation, co-precipitation and immuno-affinity isolated EVs respectively) following the MISEV guidelines25.

Workflow of human salivary extracellular vesicles isolation. Representative scheme of the workflow. Briefly, 4 mL of saliva were collected from donors and centrifuged successively at 300×g and 3000×g to remove cells and large debris and then small debris respectively. Then, whole saliva supernatant was splited in four fractions: 0.5 mL whole saliva supernatant (WS) used as a control and 1 mL dedicated to each EV isolation methods.

Particle size distribution and concentrations of EVs isolated from human saliva by nanoparticle tracking analysis

After isolation, particle size distribution and concentrations of EVs were measured using NTA (NanoSight NS300) (Fig. 2). For this experiment, EV samples from four volunteers were analyzed in triplicates. All samples were submitted to µBCA assay in order to adjust them at the same protein concentration before proceeding to NTA.

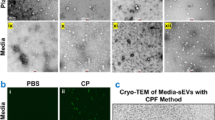

Characterization of human salivary extracellular vesicles. (A) Mean size distribution of extracellular vesicles (EV UC, Q and M) assessed by NTA (n = 4). (B) Representative pictures of EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation (EV UC), co-precipitation (EV Q) and by immuno-affinity (EV M) by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. Image bars represent 100 nm. (C) Quantification by NTA of EV particles isolated from 1 mL of human saliva (n = 4). (D) Mean size of EVs derived from saliva (n = 4). (E) Mode size of EVs derived from saliva (n = 4). (F) Particle size distribution D10, D50, and D90 corresponding to the 10% smallest particles, 50% (median), and 10% largest particles within a sample respectively (n = 4). *p < 0.05.

Our analysis revealed distinct size distributions and particle numbers. EV UC displayed the broadest size range with an average size of 264 nm (± 13 nm), followed by EV Q at 227 nm (± 7 nm), and EV M at 84 nm (± 4 nm) as shown in Fig. 2A,D. The notably smaller size of EV M could be partly attributed to the immuno-affinity method using antibody-coupled magnetic beads, which are approximately 50 nm in size according to the manufacturer. This bead influence, also observed in another study21, skews the size measurements towards smaller sizes, particularly noticeable in the D10 and mode size distributions (Fig. 2E,F). However, even the larger EV M vesicles are substantially smaller than those from EV UC and EV Q, as shown in their D90 sizes (EV UC: 422 nm ± 21; EV Q: 339 nm ± 9; EV M: 131 nm ± 13). When EVs below 100 nm were removed from analysis to account for the beads bias, the EV M size distribution was still significantly narrower than those obtained by the two other methods (Supplementary Fig. S1), confirming that immuno-affinity method tend to isolate small vesicles.

In terms of particle numbers, EV M yielded the highest count at 2.25 × 1011 particles, surpassing EV UC’s 2.34 × 1010 and EV Q’s 1.96 × 1010 (Fig. 2C). This higher count in EV M is also partially attributed to the presence of magnetic beads. When considering particle concentration normalized by protein content26, EV M demonstrated the highest concentration (1.36 × 109 particles/ml/µg), indicating a higher purity compared to EV UC (4.51 × 108 particles/ml/µg) and EV Q (1.77 × 108 particles/ml/µg), as shown in Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 2.

These findings suggest that immuno-affinity and ultracentrifugation methods yield purer EVs than co-precipitation, a result in contrast to other studies favoring co-precipitation methods for higher recovery efficiency20,27. Co-precipitation techniques tend to co-precipitate non-vesicular proteins, leading to biased protein concentration measurements in EV samples20,21,28,29,30. This discrepancy highlights the potential for higher protein contamination in EVs isolated by co-precipitation compared to the other methods, raising concerns about the purity of EVs obtained via this method.

Morphological characterization of EVs from saliva

We next sought to visualize the morphology and structural integrity of EVs using cryo-EM. The primary advantage of cryo-EM is its ability to preserve membranes in a state that closely resembles their natural condition, allowing for clear observation of lipid bilayers and internal structures of vesicles. We successfully visualized EVs under all conditions (Fig. 2B). EV UC appeared as well-defined, round vesicles with a bilayered membrane (Fig. 2B, upper left panel and supplementary Fig. S2A). In contrast, EV Q were more challenging to detect and appeared blurry (Fig. 2B, upper right panel), likely due to residual PEG interfering with image acquisition (supplementary Fig. S2B). For EV M, we also observed clear, round vesicles similar to those in the UC condition (Fig. 2B, lower panel). However, many magnetic bead aggregates were present in the microscopic field, although clearly smaller than EVs. Despite these differences, EVs isolated using all three methods could be assessed effectively by cryo-EM.

Protein content-based characterization of EVs isolated from saliva

Based on the MISEV guidelines25, we did a systematic protein quantification for all EV isolation methods and the starting WS. Twenty-seven biological samples from nine healthy volunteers were assessed. We used the µBCA kit to estimate the protein quantity in each sample (Fig. 3A). For EV M, a control using 50 µl of Microbeads alone treated in parallel of the samples was used to account for the non-specific background induced by the beads. This value was substracted to the value obtained for EV M samples in order to get more accurate measurements. As expected, whole saliva contains a huge amount of proteins, with a mean concentration of 4.7 mg/ml. Regarding EV isolation, EV UC has the lowest recovery rate, followed by EV M and EV Q (EV Q being significantly higher than EV UC and EV M (p < 0.0001) with a mean protein quantity of 43.2 µg; 195.8 µg and 99.01 µg per mL of saliva respectively.

Characterization of human salivary extracellular vesicles by protein markers. (A) Total proteins contained in human saliva and salivary EVs (n > 26). (B) Commassie blue staining of total proteins from whole saliva or EV UC, EV Q and EV M. (C) Western blot analysis of salivary markers (albumin, endosomal (TSG101) and tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, CD81)) in EV UC, EV Q and EV M protein extracts. (D) Relative quantification to WS of proteins shown in (C). Results are given as fold-change versus control whole saliva normalized at 1. (n = 4). (E) Venn diagram showing overlap between the ExoCarta Top 100 proteins list (yellow) and the salivary EV proteins in EV UC (blue), EV Q (red) and EV M (green) determined by proteomics. (F) Venn diagram showing the number of EV proteins identified in EV UC (blue), EV Q (red) and EV M (green) not identified in WS determined by proteomics. (G) Western blot analysis of mucin-16, CD59 and serum amyloid A1 biomarkers in EV UC, EV Q and EV M protein extracts. (H) Relative quantification to WS of proteins shown in (G). Results are given as fold-change versus control whole saliva normalized at 1. (n > 5). Original blots in (C, G) are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4.*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

We first analyzed the protein composition of WS and EVs isolated using UC, Q, and M methods through Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels. An equal volume (40 µl) was loaded on each lane. As shown in Fig. 3B, the global intensities observed for each condition correlated well with the relative abundance measured using the µBCA assay (Fig. 3A). The results (Fig. 3B) showed that the protein profiles of EVs differed from WS, with some proteins like mucins or albumin prominent in WS but less so in EVs. Notably, EVs from different isolation methods also displayed distinct protein patterns. EV Q closely resembled WS, EV UC showed some differences, and EV M exhibited the most distinct profile with many small discrete bands.

We further investigated specific EV markers (CD9, CD81, CD63, TSG101) and albumin (a negative EV marker) via Western blotting. Using 20 µg of protein per lane, we observed that WS had high albumin and TSG101 levels but lacked tetraspanins CD9, CD81, and CD63. EV UC samples showed all tetraspanins and TSG101 with minimal albumin, suggesting low protein contamination. EV Q contained TSG101, CD9, CD81, but CD63 was inconsistently detected and albumin contamination was significant. EV M samples had TSG101, CD9, CD63, minimal albumin, but lacked CD81, which might indicate selective EV subtype isolation or antibody binding issues. Notably, only EV UC consistently showed all tetraspanins. EV Q bands were weaker, possibly due to residual PEG buffer.

These Western blot results (Fig. 3C,D and Supplementary Fig. S3A), representative of four independent experiments using saliva from four volunteers, suggest that different EV populations are isolated by each method. The variability was more pronounced between methods than between individual samples.

In order to confirm these data at a larger scale and to study the whole proteomic landscape resulting from the different isolation methods, we performed a quantitative label free LC–MS/MS proteomic analysis on WS and the EVs isolated by the three methods. We used three biological replicates for each condition. However, one EV M sample failed to be analyzed and was removed in the subsequent analysis.

We identified 648 proteins in WS, 800 in EV UC, 711 in EV Q and 394 in EV M samples (Supplementary Table 3). For each EV isolation method, we compared their protein cargo to the top 100 EV markers. EV UC had the highest overlap with the top 100 (85), closely followed by EV Q (78), but EV M showed only a moderate overlap (66) (Fig. 3E).

To be the more stringent and robust possible, we looked at the proteins identified in all three replicates for EV UC and EV Q and the two EV M replicates (Fig. 3F). Importantly, these proteins were unique to EVs and absent from the WS samples. 140 proteins were uniquely found in EV UC, 45 in EV Q and 12 in EV M. Only 29 were identified in EV isolated by the three methods (8.5% of total proteins identified). This clearly demonstrates that the choice of EV isolation method is crucial, as it directly affects the harvested protein content and, consequently, has a significant impact on the success or failure of detecting biomarkers. To verify this last assertion, we selected three proteins known to be upregulated in several diseases and well described as strong biomarkers in their corresponding pathologies. We chose mucin-16, a cancer biomarker31, the Serum Amyloid A1 protein (SAA1), a traumatic brain injury marker32 and CD59, an early biomarker for gestational diabetes mellitus33. These three proteins were identified in the LC–MS/MS analysis with higher intensities in EVs compared to the WS.

We could confirm by WB the presence of these three proteins only in the EVs and not in WS samples (Fig. 3G). The stronger signal was always observed in EV UC, followed by EV Q. We failed to detect MUC16 and SAA1 in the EV M condition (Fig. 3G,H). The experiment was repeated seven times (Supplementary Fig. S3B, C and D). This result emphasizes the relevance and the high potential of salivary EVs for diagnostic.

MiRNA content-based characterization of EVs isolated from saliva

As we observed strong differences in the proteic cargo of EVs depending on the isolation method chosen, we wondered if the nucleic acid cargo could be also affected by it.

MiRNAs, small non-coding RNAs crucial in regulatory roles34, impact about 60% of protein-encoding genes, orchestrate cellular signaling, and can translocate to the nucleus35,36,37, making them increasingly recognized as potential biomarkers in various biofluids38,39,40 including saliva41 for many diseases40,41,42.

It is now well established that EVs contains small non-coding RNA (sncRNA) and miRNA in particular with more than 10 000 entries in Vesiclepedia (http://microvesicles.org/). Therefore, we chose to focus only on miRNA to assess the nucleic acid cargo of the method-dependent isolated vesicles.

In our study, miRNAs from WS and EVs isolated using UC, Q, and M were purified using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen), and quantified with the Qubit™ microRNA Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), as shown in Fig. 4A. We normalized the miRNA quantities to the initial saliva volume for comparison. WS had significantly more miRNA (179 ng/ml) compared to EV UC (30.9 ng/ml) and EV M (8.3 ng/ml). EV Q had a lower RNA content than WS (62.8 ng/ml) but higher than EV M, which was statistically significant (Fig. 4A). This was further confirmed by lab chip analysis (Fig. 4B).

MiRNA cargo assessment in human salivary extracellular vesicles. (A) Quantity of total miRNA contained in human saliva and extracellular vesicles (UC, Q and M) (n = 10). (B) Gel-like image of miRNA isolated from whole saliva and EVs, generated from the LabChip® GX system. (C) miRNA levels in EVs (UC, Q and M) relative to whole saliva (WS). Results are given as fold-change of whole saliva normalized at 1. (n > 9). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

For miRNA analysis, we selected six miRNAs known to be present in saliva43. Using 4 ng of RNA for reverse transcription, followed by qPCR, we found that all miRNAs were significantly enriched in EVs compared to WS, with enrichments ranging from 4- to 50-fold, varying by miRNA (Fig. 4C). This supports the notion that the primary miRNA source in saliva is EVs rather than free circulating miRNA43,44. Slight differences in miRNA expression were noted among the isolation techniques. EV Q showed the most consistent results with the smallest error bars, indicating its suitability for miRNA measurements. However, there was noticeable variability in miRNA quantities and fold changes to WS among the EVs isolated by the same method, highlighting the variability in miRNA content in EVs (Fig. 4C).

Effect of filtration on EVs isolation, recovery and subsequent analysis

In our study, we examined the impact of filtration on EV isolation, a step often recommended for improving EV purity. We modified our standard workflow (Fig. 1) to include filtration of whole saliva through 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filters before isolating EVs (Fig. 5A). For EV UC, filtration impeded protein quantification (Fig. 5B) and significantly reduced miRNA content, with the unfiltered condition yielding 5.31 ng of miRNA compared to only 2.26 ng and 2.47 ng in the 0.45 µm and 0.22 µm filtration conditions, respectively (Fig. 5C). RT-qPCR showed a substantial decrease in both miRNA recovery and target detection post-filtration, with the 0.22 µm condition slightly more affected, although not statistically significant (Fig. 5D).

Impact of filtration on saliva-derived extracellular vesicles isolated by ultracentrifugation. (A) Representative scheme of the workflow. Briefly, saliva collected from donors was centrifuged successively at 300×g and 3000×g to remove cells and large debris and then small debris respectively. Then, whole saliva supernatant was filtered on 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filter. The filtrate was subsequently used for EVs isolation as described previously. (B) Concentration of total proteins contained in EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation from 1 mL of human non-filtered saliva (NF) and 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filtered saliva (n = 3). (C) Quantity of total miRNA contained in EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation from 1 mL of human non-filtered saliva (NF) and 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm filtered saliva (n = 4). (D) miRNA levels in EVs isolated by ultracentrifugation from filtered 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm saliva relative to EVs isolated from non-filtered saliva (NF). Results are given as fold-change versus control non-filtered saliva normalized at 1. (n = 4). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Similar trends were observed in EV Q, with both protein and miRNA contents decreasing after filtration (Supplementary Fig. S5). RT-qPCR indicated reduced miRNA recovery, except for hsa-Let-7f-5p, which increased compared to the non-filtered condition (Supplementary Fig. S5C).

In contrast, protein quantities in EV M remained consistent between filtered and non-filtered conditions (Supplementary Fig. S6A, left panel). This consistency might be due to the technique’s preference for smaller vesicles, which are less impacted by filtration, or the presence of mouse immunoglobulin chains on the beads. However, the EV M samples showed significant reductions in both miRNA content (Supplementary Fig. S6B) and miRNA fold changes compared to non-filtered conditions (Supplementary Fig. S6C), similar to EV UC.

We also performed a WB to compare the unfiltered to both filtered conditions for albumin, CD63 and TSG101 (Supplementary Fig. S7). Filtration does not remove the albumin background and EV marker signal seems strongly impeded, especially for the 0.22 µm conditions.

Overall, our findings indicate that filtration, regardless of pore size (0.45 or 0.22 µm), substantially affects EV recovery in all isolation conditions and hinders subsequent analysis. Therefore, filtration of saliva prior to EV isolation is not advisable.

Discussion

In recent years, saliva has emerged as a promising biofluid for biomarker discovery, despite challenges such as variability and the presence of inhibitors and bacteria. The discovery of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in saliva6 has generated significant interest, as they may overcome these limitations. However, EV isolation and characterization in clinical practice remain complex45. Research predominantly focuses on blood, urine, and CSF29,46,47,48, with fewer studies on saliva20,30,49.

This study presents a comprehensive comparison of three EV isolation methods (ultracentrifugation, co-precipitation, and immuno-affinity) in human saliva, examining their efficiency, purity, and recovery rates. Our results show that co-precipitation and immuno-affinity kits, despite being designed for other biofluids, effectively isolate salivary EVs. However, the enrichment levels and recovery rates varied depending on the chosen method. NTA revealed significant differences in size distribution and particle concentration among the methods, suggesting the isolation of different EV subpopulations. EV Q showed a similar size distribution to EV UC but with fewer particles, indicating potential issues with buffer residue and protein aggregation, as observed in cryo-EM data (Fig. 2B and supplementary Fig. S2B). In contrast, EV M tended to isolate smaller particles efficiently, comparable to EV UC and showed well-defined vesicles with beads attached to their surface. However, MicroBeads tend to form small aggregates and are present in significant proportions in the sample. This results in a bias towards smaller sizes, which should be carefully considered when using this method. A recent study comparing eight isolation techniques (including ultracentrifugation and two PEG-based co-precipitation methods) evaluated EV concentration, size distribution, protein concentration, and purity in pooled salivary samples from young and old adults, both before and after magnetic bead immunocapture using antibodies against CD9, CD63, and CD8150. The study revealed that EV concentrations, size distributions, and purity varied by age and isolation technique. Notably, after immunocapture, age-related differences in EV concentrations were no longer observed, though the isolation technique still significantly influenced EV recovery. Immunocapture also resulted in less concentrated, smaller EVs, indicating that tetraspanin-based capture does not isolate all EVs and tends to favor smaller ones. Furthermore, the presence of bacterial EVs in saliva51, similar in size and morphology to human EVs but carrying different cargos, may contribute to the observed variations between isolation techniques.

WB analysis of isolated EVs showed distinct protein profiles for each method. For instance, the EV Q samples displayed less pronounced bands for CD9 and CD81 compared to EV UC, suggesting potential purity and recovery rate differences. Albumin detection patterns further support this, implying that EV Q also co-precipitates soluble saliva proteins. TSG101 migration profiles in EV Q samples suggest a mix of EV-isolated fractions and whole saliva, and could serve as another purity indicator for EV preparations in saliva. Similar results regarding purity and variations in tetraspanin signals were observed in the Reseco et al. article50. In this study, CD63 enrichment was maintained across all EV isolation techniques and age groups tested, whereas CD81 and flotillin-1 were more inconsistently expressed. Post-capture using beads coated with CD9, CD63, and CD81 increased the purity of the recovered EVs, although it reduced the yield, likely due to the selection of specific EV subtypes.

Proteomic analysis revealed that EV Q contained a set of proteins similar to EV UC, with a close number of Top 100 EV markers (85 vs. 78) and a small subset of uniquely identified proteins. This aligns with a recent study comparing UC and ExoQuick-CGTM, showing differentially expressed proteins in UC and PEG conditions. The enriched proteins in EV Q seemed to be related to distinct biological processes and functions, indicating selective enrichment in different EV populations20.

Interestingly, EV Q allowed the detection of known biomarkers like MUC16, CD59, and SAA1 by Western blot, albeit less intensely than EV UC, confirming its potential for biomarker detection in saliva. ELISA assays can be highly effective for biomarker detection due to their sensitivity and quantitative capabilities. However, we did not use them in this study because we were evaluating an immuno-isolation method concurrently. In the future, it would be beneficial to use ELISA assays for detecting EV biomarkers in combination with ultracentrifugation or co-precipitation methods, as this could potentially increase both sensitivity and precision.

The immuno-affinity method isolates smaller particles efficiently, comparable to EV UC, but exhibited an unexpected lack of CD81 in WB and proteomic analysis, suggesting selective EV surface protein isolation. This was unexpected, as the beads are designed to recognize the three tetraspanins CD9, CD63 and CD81. A plausible explanation would be that we preferentially isolate EVs having CD63 and CD9 on their surface due to a higher affinity for the subpopulations carrying these EV markers. A subset of EVs harbouring the CD81 tetraspanin would be captured in a smaller proportion, resulting in a too faint signal that failed to be detected by WB, in line with52 where they suggest that not all of the EVs carrying an epitope are captured in a single step. Alternatively, steric hindrance could impede the antibody binding to its target. Furthermore, the overall protein content and the Top 100 EV markers in EV M weakly overlapped with those in EV UC and EV Q, highlighting the selective nature of the immuno-affinity approach. This method, which enriches for small EVs co-expressing CD9, CD63, and CD81, likely targets a specific subpopulation of exosomes originating from the endosomal pathway, marked by proteins like syntenin-1 and TSG101, as described in53. However, this selectivity may restrict the full EV proteome representation. In contrast, ultracentrifugation captures a broader spectrum of EV subtypes, including large, medium, and various small EVs, some of which may lack these tetraspanins or be enriched with other markers associated with the plasma membrane or extracellular matrix. This underscores the importance of selecting the appropriate isolation method to capture distinct EV subpopulations with unique protein compositions and biological functions.

Our study also evaluated miRNA content in isolated EVs versus whole saliva. All three methods enriched miRNAs within EVs, with co-precipitation providing the most consistent results for RT-qPCR miRNA analysis. However, filtration steps, commonly assumed to improve EV purity, significantly reduced overall EV recovery, suggesting that miRNAs are predominantly enclosed within EVs rather than in free form in saliva. When assessing the remaining contaminants (albumin) and some of the EV markers (TSG101 and CD63), we found no signal in the filtered EV UC samples (Supplementary Fig. S7). This indicates a loss of integrity of the EVs during the filtration process. If the pressure exerted on the filter is too strong and/or the pores become obstructed, it could result in significant degradation of the EVs. As a result, a substantial proportion of EVs and their protein cargo could be lost in the supernatant, leaving few to no intact EVs pelleted after ultracentrifugation. The loss of signal for TSG101 and CD63 in EV M samples filtered with 0.22 µm filters, and the fainter signal with 0.45 µm filters, further supports this observation. Surprisingly, the EV Q samples appear relatively unaffected by the filtration. While filtration does not improve purity, the signal for EV markers TSG101 and CD63 seems to increase with 0.45 µm filtration but decreases again with 0.22 µm filtration. Given that the co-precipitation method often results in nonspecific signals, these variations are not unexpected. For this study, we used PVDF filters, as they have proven to be efficient in other studies for improving EV isolation54. PVDF filters offer several advantages, such as consistent performance and reliability across various applications. Since we aimed to assess the protein and miRNA content from EV cargos and saliva, PVDF filters were a pertinent choice. Using a low protein-binding filter like PVDF minimizes the loss of nucleic acids due to protein adherence to the filter, which is crucial for applications requiring high yield and purity of nucleic acids. It could be interesting to extend this type of characterization with other types of filters, such as Nylon, cellulose acetate, or PTFE. Additionally, buffer exchange/filtration units with a small KD range might represent better alternatives than filter pores for preserving EV integrity while improving purity. Further experiments will be necessary to explore these possibilities.

In conclusion, our findings emphasize that the choice of EV isolation method significantly impacts the enriched EV subpopulations, size, concentration, and protein cargo. The co-precipitation method, despite some contamination, offers a rapid, cost-effective approach for large-scale diagnostic applications. It highlights the need for standardized protocols and reinforces the potential of salivary EVs for non-invasive biomarker discovery. However, further large-scale studies are necessary to fully understand the proteomic and sncRNAome landscape of EVs isolated by these methods. Our research contributes to advancing knowledge in salivary EVs, positioning them as a powerful tool for non-invasive biomarker research.

Materials and methods

Saliva collection and sample processing

Unstimulated saliva samples were obtained from nine healthy males volunteers aged between 18 and 40 years old and collected in the morning (9:00–10:00 AM). Subjects were asked to refrain from eating, drinking or smoking for at least 1 h prior to saliva collection. The absence of blood contamination was checked by visual inspection. Whole saliva was collected into polystyrene tubes, immediately kept on ice and centrifuged at 300×g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove cells and large debris. The supernatant was separated from the pellet and centrifuged again at 3000×g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove residual organelles, cell fragments and small debris. The whole saliva supernatant was separated from the pellet and kept on ice for EV isolation. A minimum of 4 ml of saliva was collected each time by participant, except for the filtration experiments where volounteers were asked to give at least 15 ml of saliva. Samples were analysed individually and were never pooled in this study. Each “n” mentioned in the experiments represents an individual biological replicate. For the purpose of some experiments, an optional filtration step was perfomed subsequently. Briefly, the whole saliva supernatent was filtered through 0.45 µm or 0.22 μm PVDF syringe filters (Merck) before proceeding to the next step. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants signed informed consent prior to participating as part of an ethically approved study by a French national ethic committee (CPP-NORD OUEST III) on April 21, 2023 (23.00930.000169). The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06149351).

Isolation and concentration of EVs

Ultracentrifugation

One mL of the WS was diluted with 24 mL of PBS and transferred to 50 mL, Open-Top Thickwall Polypropylene Tube (Beckman Coulter) for ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g for 1 h at 4 °C (JXN-30 centrifuge, JA-30.50 Ti Rotor, Beckman Coulter). The pellet was washed with PBS and centrifuged again at 100,000×g for 1 h at 4 °C to remove soluble contaminant. The final pellet was resuspended in 100 μl PBS and then kept on ice or at − 80 °C for further analysis.

Co-precipitation

The extracellular vesicles from WS were isolated using miRCURY® Exosome Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. This extracellular vesicle isolation process relies on the sequestration of water molecules that typically surround particles in suspension, forming a hydration layer. By mixing the starting sample with the Precipitation Buffer, the hydration of subcellular particles is reduced, facilitating the precipitation of even small nanoparticles using a low-speed centrifugation step. Briefly, 400 µL of Precipitation Buffer B were added in 1 mL of whole saliva supernatant and incubated for 60 min at 4 °C. At the end of the incubation time, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 min at room temperature, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 100 µL of Resuspension Buffer and then kept on ice or at − 80 °C for further analysis.

Immunomagnetic separation of EVs

The extracellular vesicles from WS were isolated using Exosome Isolation Kit Pan, Human (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat N°: 130-111-572) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The isolation relies on a positive selection using MicroBeads recognizing the tetraspanin proteins CD9, CD63, and CD81. Briefly, 50 µL of Exosome Isolation MicroBeads were added in 1 mL of WS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was applied to an equilibrated µ column (100 µL of equilibration buffer, then washed 3× with 100 µL of isolation buffer) and placed in a µMACS Separator attached to the MACS MultiStand (Miltenyi Biotec). Afterwards, µ column was washed 4× with 200 µL of isolation buffer. EVs and beads were co-eluted outside the magnetic field with 100 µL of isolation buffer using a dedicated plunger. EVs and beads were then kept on ice or at − 80 °C for further analysis. To determine the non-specific background potentially induced by the MicroBeads on µBCA measurements, 50 µl of MicroBeads were processed in the same way as the samples.

Characterization of EVs

EVs were characterized as recommended by the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles25. EV size and particles number were measured by Nanoparticles Tracking Analysis using the NanoSight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical). EVs integrity and the absence of large aggregates were analysed by cryo-EM using the JEOL 2200 FS transmission electron microscope (Jeol). Small RNA content was isolated using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen). Protein content was measured using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and characterized by western blot, as described55. EVs were used freshly prepared.

Proteomics

LC–MS/MS analysis were done at Plateforme de Proteomique Fonctionnelle de Montpellier (FPP). Triplicates of WS, EV UC, EV Q and EV M were analysed with 14.5 µg of proteins per sample. Briefly, protein digestion was performed using S-Trap micro columns (ProtiFi) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Peptide samples were injected for analysis using a nano flow HPLC (RSLC U3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a mass spectrometer equipped with a nanoelectrospray source (Q Exactive HF, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were separated on a capillary column (0.075 mm × 500 mm, Acclaim Pepmap 100, reverse phase C18, NanoViper, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following a gradient of 2–40% buffer B in 128 min (A = 0.1% formic acid B = 0.1% formic acid, 80% acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 300 nl/min. Spectra were recorded via Xcalibur 4.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the 128.meth method. The spectral data were analyzed using MaxQuant v2030 and Perseus v16150 software, using the leading FPP v3.5 script. RefProteome_HUMAN-cano_2023_03_UP000005640_559292.fasta databases and a base of common contaminants, with the following fixed modification: Carbamidomethylation (C) and the following variable modifications: Oxidation (M); Acetyl (Protein N-term) were used. Data validation was performed with the following filters: FDR peptides and proteins at 1%.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Samples were lysed in RIPA buffer containing a protease inhibitor (Roche) and Laemmli buffer with 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol. A total of 20 μg of protein was loaded onto a homemade 12.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel and run at 200 V for 50 min. Proteins were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane using a Trans-Blot cell (Bio-Rad) for 1 h. Following the transfer, the membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS-Tween and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-CD9 (ab263019; 1:1000), anti-CD63 (ab134045; 1:1000), anti-CD81 (ab109201; 1:1000), anti-TSG101 (ab125011; 1:1000), anti-albumin (ab19180; 1:20,000), anti-mucine-16 (ab110640; 1:1000), anti-SAA1 (ab207445; 1:1000) from Abcam, and anti-CD59 (HPA026494; 1:400) from Sigma. The membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma). Detection was performed using Clarity Max Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad), and the signals were quantified with a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) and ImageJ software. Results are expressed as fold changes to evaluate the relative abundance of proteins of interest in EVs compared to WS. Fold changes were calculated as the ratio of the intensity of the target band in each EV isolation method to the intensity of the target band corresponding to the WS sample for each participant.

Bioinformatics tools

The enrichment in EV proteins was checked by comparison with ExoCarta Top 100 list (http://www.exocarta.org)56. The visualization of Venn diagram was performed using online Draw Venn Diagram tool (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total small RNA was extracted from EV and WS samples using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen). miRNA quantification was carried out with the Qubit™ microRNA Assay Kits (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. LabChip analysis was conducted to assess the size distribution of small RNAs according to the manufacturer’s instructions (PerkinElmer). The LabChip GX assays adapt traditional gel electrophoresis principles to a chip format, significantly reducing separation time and providing automated sizing and quantification data in a digital format. Reverse transcription was performed on 4 ng of RNA using the miRCURY® LNA® RT Kit (Qiagen). RT-qPCR was performed on 40 pg of cDNA using specific primers (Supplementary Table 1) and the miRCURY® LNA® miRNA SYBR® Green PCR Kit (Qiagen). Values were normalized to the quantity of miRNA and expressed as fold changes to evaluate the relative abundance of the miRNA of interest in EVs compared to WS. Fold changes were calculated using the 2 − ΔCT formula, where ΔCT represents the difference between the CT of the target miRNA for each EV isolation method and the CT corresponding to the WS sample for each participant.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad 9 Prism Software. Data distribution was assessed using the normality test. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was done to compare one group to the control normalized to 1. If controls were not normalized, the statistical analyses between three groups were compared using the the Friedman’s test when values were paired and non-parametric, or Kruskal–Wallis test when values were unpaired and non-parametric, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparizon. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data have been provided within the manuscript and its supporting information files.

References

van Niel, G., D’Angelo, G. & Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2017.125 (2018).

Caby, M. P., Lankar, D., Vincendeau-Scherrer, C., Raposo, G. & Bonnerot, C. Exosomal-like vesicles are present in human blood plasma. Int. Immunol. 17, 879–887. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxh267 (2005).

Pisitkun, T., Shen, R. F. & Knepper, M. A. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 13368–13373. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403453101 (2004).

Admyre, C. et al. Exosomes with immune modulatory features are present in human breast milk. J. Immunol. 179, 1969–1978. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1969 (2007).

Bachy, I., Kozyraki, R. & Wassef, M. The particles of the embryonic cerebrospinal fluid: How could they influence brain development?. Brain Res. Bull. 75, 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.010 (2008).

Ogawa, Y., Kanai-Azuma, M., Akimoto, Y., Kawakami, H. & Yanoshita, R. Exosome-like vesicles with dipeptidyl peptidase IV in human saliva. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31, 1059–1062. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.31.1059 (2008).

Konoshenko, M. Y., Lekchnov, E. A., Vlassov, A. V. & Laktionov, P. P. Isolation of extracellular vesicles: General methodologies and latest trends. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 8545347. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8545347 (2018).

Hessvik, N. P. & Llorente, A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9 (2018).

Jeppesen, D. K., Zhang, Q., Franklin, J. L. & Coffey, R. J. Extracellular vesicles and nanoparticles: Emerging complexities. Trends Cell Biol. 33, 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcb.2023.01.002 (2023).

Sun, R. et al. Changes in the morphology, number, and pathological protein levels of plasma exosomes may help diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 73, 909–917. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190497 (2020).

Mandel, I. D. Salivary diagnosis: Promises, promises. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 694, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18336.x (1993).

Jasim, H., Carlsson, A., Hedenberg-Magnusson, B., Ghafouri, B. & Ernberg, M. Saliva as a medium to detect and measure biomarkers related to pain. Sci. Rep. 8, 3220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21131-4 (2018).

Schneider, F. S. et al. Performances of rapid and connected salivary RT-LAMP diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2 infection in ambulatory screening. Sci. Rep. 12, 2843. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04826-7 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. Saliva—A new opportunity for fluid biopsy. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 61, 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-0793 (2023).

Ogawa, Y. et al. Proteomic analysis of two types of exosomes in human whole saliva. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.34.13 (2011).

Bobrie, A., Colombo, M., Krumeich, S., Raposo, G. & Thery, C. Diverse subpopulations of vesicles secreted by different intracellular mechanisms are present in exosome preparations obtained by differential ultracentrifugation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v1i0.18397 (2012).

Weng, Y. et al. Effective isolation of exosomes with polyethylene glycol from cell culture supernatant for in-depth proteome profiling. Analyst 141, 4640–4646. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6an00892e (2016).

Garcia-Romero, N. et al. Polyethylene glycol improves current methods for circulating extracellular vesicle-derived DNA isolation. J. Transl. Med. 17, 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-019-1825-3 (2019).

Lee, H., Kang, S. J., Lee, J., Park, K. H. & Rhee, W. J. Isolation and characterization of urinary extracellular vesicles from healthy donors and patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23137134 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Deep dive on the proteome of salivary extracellular vesicles: comparison between ultracentrifugation and polymer-based precipitation isolation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 413, 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-020-03004-w (2021).

Mussack, V., Wittmann, G. & Pfaffl, M. W. Comparing small urinary extracellular vesicle purification methods with a view to RNA sequencing-Enabling robust and non-invasive biomarker research. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 17, 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdq.2019.100089 (2019).

Chhoy, P., Brown, C. W., Amante, J. J. & Mercurio, A. M. Protocol for the separation of extracellular vesicles by ultracentrifugation from in vitro cell culture models. STAR Protoc. 2, 100303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100303 (2021).

Liang, L. G. et al. An integrated double-filtration microfluidic device for isolation, enrichment and quantification of urinary extracellular vesicles for detection of bladder cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 46224. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46224 (2017).

Sidhom, K., Obi, P. O. & Saleem, A. A review of exosomal isolation methods: Is size exclusion chromatography the best option?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186466 (2020).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 13, e12404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12404 (2024).

Webber, J. & Clayton, A. How pure are your vesicles?. J. Extracell. Vesicles https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v2i0.19861 (2013).

Van Deun, J. et al. The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J. Extracell. Vesicles https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v3.24858 (2014).

Park, S. et al. The profiles of microRNAs from urinary extracellular vesicles (EVs) prepared by various isolation methods and their correlation with serum EV microRNAs. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 160, 108010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108010 (2020).

Alvarez, M. L., Khosroheidari, M., Kanchi Ravi, R. & DiStefano, J. K. Comparison of protein, microRNA, and mRNA yields using different methods of urinary exosome isolation for the discovery of kidney disease biomarkers. Kidney Int. 82, 1024–1032. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2012.256 (2012).

Zlotogorski-Hurvitz, A. et al. Human saliva-derived exosomes: Comparing methods of isolation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 63, 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1369/0022155414564219 (2015).

Zhang, M., Cheng, S., Jin, Y., Zhao, Y. & Wang, Y. Roles of CA125 in diagnosis, prediction, and oncogenesis of ovarian cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 1875, 188503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188503 (2021).

Carabias, C. S. et al. Serum amyloid A1 as a potential intracranial and extracranial clinical severity biomarker in traumatic brain injury. J. Intensive Care Med. 35, 1180–1195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066619837913 (2020).

Andrews, C. et al. Plasma-glycated CD59 as an early biomarker for gestational diabetes mellitus: Prospective cohort study protocol. BMJ Open 12, e054773. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054773 (2022).

Nam, J. W. et al. Global analyses of the effect of different cellular contexts on microRNA targeting. Mol. Cell 53, 1031–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.013 (2014).

Diener, C., Keller, A. & Meese, E. Emerging concepts of miRNA therapeutics: from cells to clinic. Trends Genet. 38, 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2022.02.006 (2022).

Karp, X. & Ambros, V. Developmental biology. Encountering microRNAs in cell fate signaling. Science 310, 1288–1289. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1121566 (2005).

Gebert, L. F. R. & MacRae, I. J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7 (2019).

Tolle, A., Blobel, C. C. & Jung, K. Circulating miRNAs in blood and urine as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for bladder cancer: An update in 2017. Biomark. Med. 12, 667–676. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm-2017-0392 (2018).

Ahlberg, E. et al. Breast milk microRNAs: Potential players in oral tolerance development. Front. Immunol. 14, 1154211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1154211 (2023).

Gui, Y., Liu, H., Zhang, L., Lv, W. & Hu, X. Altered microRNA profiles in cerebrospinal fluid exosome in Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease. Oncotarget 6, 37043–37053. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.6158 (2015).

Hofmann, L. et al. Comparison of plasma- and saliva-derived exosomal miRNA profiles reveals diagnostic potential in head and neck cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 971596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.971596 (2022).

Wang, L. & Zhang, L. Circulating exosomal miRNA as diagnostic biomarkers of neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13, 53. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2020.00053 (2020).

Bahn, J. H. et al. The landscape of microRNA, Piwi-interacting RNA, and circular RNA in human saliva. Clin. Chem. 61, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.230433 (2015).

Gallo, A., Tandon, M., Alevizos, I. & Illei, G. G. The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One 7, e30679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030679 (2012).

Rezaie, J., Feghhi, M. & Etemadi, T. A review on exosomes application in clinical trials: Perspective, questions, and challenges. Cell Commun. Signal. 20, 145. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12964-022-00959-4 (2022).

Serrano-Pertierra, E. et al. Characterization of plasma-derived extracellular vesicles isolated by different methods: A comparison study. Bioengineering (Basel) 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering6010008 (2019).

Helwa, I. et al. A comparative study of serum exosome isolation using differential ultracentrifugation and three commercial reagents. PLoS One 12, e0170628. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170628 (2017).

Sjoqvist, S., Otake, K. & Hirozane, Y. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles by proximity extension assay: A comparative study of four isolation kits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21249425 (2020).

Jangholi, A. et al. Method optimisation to enrich small extracellular vesicles from saliva samples. Clin. Transl. Med. 13, e1341. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.1341 (2023).

Reseco, L. et al. Characterization of extracellular vesicles from human saliva: Effects of age and isolation techniques. Cells 13, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13010095 (2024).

Han, P., Bartold, P. M. & Ivanovski, S. The emerging role of small extracellular vesicles in saliva and gingival crevicular fluid as diagnostics for periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 57, 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jre.12950 (2022).

Campos-Silva, C. et al. A simple immunoassay for extracellular vesicle liquid biopsy in microliters of non-processed plasma. J. Nanobiotechnol. 20, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-022-01256-5 (2022).

Kowal, J. et al. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, E968-977. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1521230113 (2016).

Xu, Y. F. et al. Isolation of extra-cellular vesicles in the context of pancreatic adenocarcinomas: Addition of one stringent filtration step improves recovery of specific microRNAs. PLoS One 16, e0259563. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259563 (2021).

Mahmood, T. & Yang, P. C. Western blot: Technique, theory, and trouble shooting. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 4, 429–434. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.100998 (2012).

Keerthikumar, S. et al. ExoCarta: A web-based compendium of exosomal Cargo. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 688–692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.019 (2016).

Acknowlegements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Marie Morille, Institut Charles Gerhardt Montpellier, UMR 5253CNRS-ENSCM-UM, Equipe Matériaux Avancés pour la Catalyse et la Santé, Montpellier, for her valuable technical assistance for nanoparticles tracking analysis and Dr. Josephine Lai Kee Him and Mrs. Aurelie Ancelin, Centre de Biochimie Structurale, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, INSERM, for their Cryo-EM analysis. Mass spectrometry was carried out using the facilities of the Montpellier Proteomics Platform (PPM, BioCampus Montpellier). We also thank all the study participants.

Funding

This project was supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and ALCEN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: J.B., F.M. and M.K. Acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J.B., F.M. and M.K. Statistical analysis: J.B. Funding acquisition: F.M. All authors critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boulestreau, J., Molina, L., Ouedraogo, A. et al. Salivary extracellular vesicles isolation methods impact the robustness of downstream biomarkers detection. Sci Rep 14, 31233 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82488-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82488-3

This article is cited by

-

Decoding bacterial extracellular vesicles: A review on isolation and characterization techniques

Archives of Microbiology (2026)

-

Extracellular vesicle-associated transcriptomic and proteomic biomarkers show in vitro potential for vandetanib treatment monitoring in anaplastic thyroid cancer

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Deciphering Molecular and Signaling Pathways of Extracellular Vesicles-Based Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease

Molecular Neurobiology (2025)