Abstract

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs), due to their high computational and memory requirements, face significant challenges in deployment on resource-constrained devices. Network Pruning, an essential model compression technique, contributes to enabling the efficient deployment of DCNNs on such devices. Compared to traditional rule-based pruning methods, Reinforcement Learning(RL)—based automatic pruning often yields more effective pruning strategies through its ability to learn and adapt. However, the current research only set a single agent to explore the optimal pruning rate for all convolutional layers, ignoring the interactions and effects among multiple layers. To address this challenge, this paper proposes an automatic Filter Pruning method with a multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm QMIX, named QMIX_FP. The multi-layer structure of DCNNs is modeled as a multi-agent system, which considers the varying sensitivity of each convolutional layer to the entire DCNN and the interactions among them. We employ the multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm QMIX, where individual agent contributes to the system monotonically, to explore the optimal iterative pruning strategy for each convolutional layer. Furthermore, fine-tuning the pruned network using knowledge distillation accelerates model performance improvement. The efficiency of this method is demonstrated on two benchmark DCNNs, including VGG-16 and AlexNet, over CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. Extensive experiments under different scenarios show that QMIX_FP not only reduces the computational and memory requirements of the networks but also maintains their accuracy, making it a significant advancement in the field of model compression and efficient deployment of deep learning models on resource-constrained devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep Convolutional Neural Networks(DCNNs) have achieved groundbreaking advancements in domains such as computer vision, natural language processing, and speech recognition. In computer vision, DCNNs have achieved state-of-the-art performance in image classification, object detection, semantic segmentation, and image generation1,2,3,4,5,6. Recent research has also extended to medical image encryption, demonstrating the potential in enhancing security and efficiency7. In natural language processing, DCNNs combined with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have significantly improved machine translation and text summarization systems8. Recent researches have also shown promise in modeling complex linguistic and cognitive processes9,10. In addition, in speech recognition, the use of DCNNs has led to more accurate acoustic models, contributing to better performance in automatic speech recognition systems11.

However, with the deep learning tasks becoming increasingly complex, DCNNs tend to grow larger in scale, demanding dramatic computational resources12,13. Model compression accelerates the inference process by reducing the model scale and computational complexity, thereby facilitating deployment and real-time inference in practical applications. Research focusing on model compression techniques for DCNNs has become indispensable. It plays a pivotal role in making deep learning feasible on resource-constrained platforms such as mobile devices, embedded systems, or edge computing devices. The model compression techniques primarily conclude network pruning, parameter quantization, low-rank decomposition, and knowledge distillation14. Network pruning and knowledge distillation are the two most widely used techniques among them.

Network pruning effectively reduces the model parameters and model computation by pruning the units while maintaining the original model performance as much as possible15. The network pruning process typically involves three steps: (1) Evaluate the importance of units and select the unimportant units for pruning. (2) According to the rule-based prune strategy, iteratively removes relatively unimportant units to reduce the model scale. (3) Fine-tuning the pruned model to improve model performance. The unit importance evaluation function, pruning strategy, and fine-tuning method are key to the effectiveness of network pruning. This paper focuses on iterative filter pruning of DCNNs, considering that when the pruning unit is the filter in convolutional layers, it can be better matched with hardware accelerators to achieve efficient computations, such as FPGAs and ASICs16,17. In the experiments, we define six explainable feature importance evaluation functions to identify the relatively unimportant filters. By comparing the outcomes of different evaluation functions, the most effective one can be selected for a given scenario or even combined. This approach aims to demonstrate that the proposed method can be more adaptable and generalizable by using multiple evaluation functions.

Traditional rule-based network pruning is limited by the rules set by experts, making it difficult to achieve a globally optimal solution. These methods often rely heavily on domain-specific knowledge and can be highly subjective, limiting their adaptability and generalization across different network architectures. Reinforcement Learning (RL)–based automatic pruning offers a promising alternative by mitigating these issues and reducing subjectivity. RL enables the discovery of optimal pruning policies through interaction with the environment, allowing for more dynamic and adaptive pruning strategies. However, current RL-based research primarily uses a single agent to explore the optimal pruning rate for all convolutional layers, neglecting the complex interactions and effects between multiple layers18,19,20.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel approach that integrates Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) for more effective pruning. Six filter importance evaluation functions are defined to capture different aspects of filter importance. These functions serve as the basis for our MARL framework, where each agent is responsible for optimizing the pruning rate of a specific layer. By using the MARL algorithm, the agents can collaborate effectively, taking into account the interdependencies between different layers.

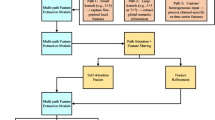

The QMIX algorithm21 is a well-established benchmark in MARL, known for its ability to solve global optimization problems through Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE). QMIX stands for “Q-value Mixing,” which refers to the process of combining the Q-values of individual agents to form a joint Q-value that represents the overall utility or reward of the team’s actions. Motivated by the principles of MARL and the effectiveness of the QMIX algorithm, we propose a DCNN pruning framework based on the QMIX algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Each convolutional layer is treated as an agent, and the entire DCNN serves as the environment, forming a multi-agent system. Thus, the network pruning task is modeled as a cooperative game. The common goal of all agents is to ensure that the pruned network meets the pruning rate constraint while minimizing the model’s prediction loss as much as possible.

In addition, Knowledge Distillation(KD)22 draws upon the educational concept of transferring knowledge from teacher to student. It transfers the knowledge of a large-scale Teacher Network (T-Net) to a small-scale Student Network (S-Net), where the T-Net is pre-trained with good performance. Therefore, the S-Net can efficiently learn the generalization of the T-Net while remaining small in scale. Motivated by this, we fine-tune the pruned model utilizing KD by setting the original model as T-Net and the pruned model as S-Net.

In conclusion, our primary contribution can be summarized as follows:

-

We propose a filter pruning method based on the multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm QMIX to explore the optimal pruning rate for each agent(layer). It is an automatic network pruning method.

-

We design an algorithm that integrates network pruning with knowledge distillation, i.e., fine-tuning the pruned model based on KD to accelerate performance improvement.

-

We validate the efficiency of the proposed method for DCNN pruning on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, including VGG-16 and AlexNet. The experimental results show that the QMIX_FP achieves competitive parameter compression and the FLOPs reduction while maintaining accuracy similar to the original network.

The layout of this paper is organized as follows. We overview related works about existing network pruning methods in the Sect. “Related work.” Section “Methodology” describes our approach to automatic filter pruning based on multi-agent reinforcement learning. We present experimental results and provide a comprehensive analysis of the findings in the Sect. “Experiments,” followed by the Sect. “Conclusions.”

Related work

Network pruning has attracted significant attention in deep learning as an effective model compression technique. It reduces the model scale and computational complexity by removing redundant weights or entire structural components within the neural network while maintaining the performance of the original model to the greatest extent. Research on network pruning has experienced rapid development, including exploring pruning strategies, optimization objectives, automation methods, and so on23,24.

According to the granularity of the pruning unit, network pruning methods can be divided into unstructured pruning (fine-grained) and structured pruning (coarse-grained)14. Unstructured pruning methods can remove neuron connections (weights) independently. In 2015, Han et al.25 conducted the first real research on deep neural network pruning. It prunes the connections whose absolute values of weight parameters are lower than the threshold and proposes the three-stage iterative pruning process for the first time. This method, however, can lead to highly sparse models that are difficult to deploy on standard hardware. This team further proposed the “Deep Compression” method26. They implemented weight quantization to facilitate weight sharing and applied Huffman coding to achieve better compression. Despite its effectiveness, the method requires additional steps like quantization and coding, which can be complex and time-consuming. Yang et al.27 proposed the energy-aware weight pruning algorithm for CNNs that directly uses energy consumption estimation to guide the pruning process and then locally fine-tuned with a closed-form least-square solution to quickly restore the accuracy. Sanh et al.28 proposed movement pruning, a method that selects weights that tend to move away from zero and applies it to pre-trained language representations (such as BERT). However, these approaches may not generalize well to different hardware platforms.

Conversely, structured pruning focuses on removing entire channels, filters, or layers. Structured pruning methods maintain the regularity of the model structure, making them more hardware-friendly and easier to implement on existing platforms. However, they may not achieve the same level of compression as unstructured pruning. He et al.29 introduced an iterative two-step algorithm to channel prune by a LASSO regression-based channel selection and least square reconstruction. This method can effectively reduce the model size but may sacrifice some accuracy. Li et al.30 pruned filters together with their connecting feature maps from CNNs to reduce the computation costs significantly and can work with existing efficient BLAS libraries for dense matrix multiplications. Liu et al.31 made the scaling factors in batch normalization layers towards zero with \(L_1\) regularization to identify insignificant channels and prune. This approach can lead to more compact models but requires careful tuning of hyperparameters. Zhuang et al.32 improved this evaluation method by proposing a polarization regularizer, pushing scaling factors of unimportant neurons to 0 and others to a value \(a > 0\). This method enhances the robustness of the pruning process. In summary, structured pruning methods maintain the regularity of the model structure, making them more hardware-friendly and easier to implement on existing platforms, which is why this paper chooses the filter-based structured pruning method.

According to the pruning process, network pruning methods can be categorized into traditional rule-based and automatic RL-based. Rule-based methods typically execute the three-stage iterative pruning process25, where the pruning rate at each step and the total number of iterative are designed in advance33,34. Instead of being confined by subjective rules and hyper-parameter design, some researchers have formulated the network pruning problem as an RL problem to explore optimal solutions automatically. He et al.18 proposed AutoML for Model Compression (AMC), which leverages reinforcement learning to provide the pruning strategy layer-wise. Gupta et al.20 built upon AMC and contributed an improved framework based on Deep Q-Network(DQN) that provides rewards at every pruning step. Camci et al.35 introduced a deep Q-learning-based pruning method called QLP, which is weight-level unstructured pruning. Feng et al.19 proposed a filter-level pruning method based on the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient(DDPG) algorithm. Unfortunately, in existing single-agent RL-based pruning methods, the agent prunes only one layer at each time step, which fails to capture the complex dependencies among multiple layers. This limitation can lead to suboptimal pruning decisions, as the performance of one layer can significantly influence that of subsequent layers. In contrast, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) can better handle these challenges by allowing multiple agents to collaborate and make decisions, thereby improving the overall pruning efficiency and effectiveness.

Existing research has been deeply involved in network pruning for DCNNs, but there are some limitations and untapped potentials in this area. In this paper, we aim to fill the gap in the existing work and propose automatic filter pruning by MARL, which has been under-explored.

Methodology

Our proposed network pruning method, named QMIX_FP, is shown in Fig. 2. This figure provides a comprehensive overview of our approach. Fig. 2b demonstrates explicitly how we utilize the MARL algorithm QMIX for pruning. Here, each agent aligns with a convolutional layer in the DCNN. The network architecture at time step \(t\) is represented by the state \(s_t\), while \(a_t\) represents the pruning decision made at that time step. The agents progressively test different pruning techniques until the target pruning rate is met, ultimately shaping the pruned network. Figure 2a breaks down the pruning steps at each time step. Once the pruning target is reached, Fig. 2c outlines the distillation phase, where we refine the pruned network and enhance its performance through knowledge distillation. In this section, we initially frame the task of filter-level pruning for DCNNs. We then provide a thorough examination of QMIX_FP, detailing our feature evaluation metrics, the QMIX-driven pruning mechanism, and the KD-based fine-tuning process.

Assume that DCNN contains L convolutional layers. For the i-th convolutional layer \(L_i\), the weight of all filters is denoted as \(\varvec{w}_i \in \mathbb {R}^{n_{i} \times n_{i-1} \times d_i \times d_i}\), where \(d_i\) is the kernel size, \(n_{i-1}\) and \(n_{i}\) are input channels and output channels, respectively. \(\varvec{w}_{i,j} \in \mathbb {R}^{n_{i-1} \times d_i \times d_i}\) indicates the j-th filter of \(L_i\). Meanwhile, we denote the bias of \(L_i\) is \(\varvec{b}_i\), and the remaining parameter of DCNN other than the convolutional layer is \(\varvec{w}_0\). Thereby, the parameter of DCNN representes as \(W=\left\{ \varvec{w}_0, \left( \varvec{w}_1, \varvec{b}_1\right) ,\left( \varvec{w}_2, \varvec{b}_2\right) , \ldots , \left( \varvec{w}_L, \varvec{b}_L\right) \right\}\). Consider the classification dataset \(D = \left\{ X = \left\{ \varvec{x}_0, \varvec{x}_1, \ldots , \varvec{x}_{N-1}\right\} , Y=\left\{ y_0, y_1, \ldots , y_{N-1}\right\} \right\}\), where \(y_n\) is the ground truth of input \(\varvec{x}_n\) and the number of samples is N. For the image classification task, the optimization objective during model training is to minimize the prediction loss function

where \(\mathbb {I}(\cdot )\) indicator function and \(\hat{y}_n\) is the predict label of input \(\varvec{x}_n\).

The filter-level pruning involves removing relatively unimportant filters from the convolutional layers without changing the topology structure and depth of DCNN. After pruning, the parameters of the pruned network are updated to \(W^{\prime }=\left\{ \varvec{w}_0^{\prime }, \left( \varvec{w}_1^{\prime }, \varvec{b}_1^{\prime }\right) ,\left( \varvec{w}_2^{\prime }, \varvec{b}_2^{\prime }\right) , \ldots , \left( \varvec{w}_L^{\prime }, \varvec{b}_L^{\prime }\right) \right\}\). To apply mathematical notation for description conveniently, we constrain the \(W^{\prime }\) to be the same dimension as the W. Thus, the optimization objective of the filter pruning task is to minimize the prediction loss of the pruned network when satisfying the overall pruning rate constraint B, i.e.,

where \(\left\| \cdot \right\| _0\) is \(l_0\) norm. Intuitively, the proportion of filters retained in \(W^{\prime }\) should be less than or equal to \(1-B.\) Here, \(B\) represents the overall pruning rate constraint for the entire DCNN.

Feature evaluation

The feature evaluation function for filter importance computing directly influences the effectiveness of DCNN network pruning with the given pruning rate. Filters play an important role in image understanding and feature extraction in DCNN. The input image data undergoes convolution with filters in the convolutional layer, resulting in feature maps, where each filter corresponds to a feature map. Typically, an activation function is applied to these feature maps to introduce nonlinearity and increase the expressiveness of the model, resulting in activation maps. In this work, we choose the classic ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) as the activation function.

Therefore, the importance of filters can be evaluated based on their inherent properties or the information representations generated by the filters, such as feature maps and activation maps. We denote the feature map produced by filter \(\varvec{w}_{i}\) as \(F_{i}=\left\{ \varvec{F}_{i,1},\varvec{F}_{i,2},\ldots ,\varvec{F}_{i,n_i}\right\}\) and the activation map produced by \(F_{i}\) as \(A_{i}=\left\{ \varvec{A}_{i,1},\varvec{A}_{i,2},\ldots ,\varvec{A}_{i,n_i}\right\}\). Considering the explainability of network pruning, we define six feature importance evaluation functions based on feature attribution theory in explainable artificial intelligence36 to demonstrate the adaptability and generalizability of our proposed method. According to the objects used for calculating the importance of filter \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\), we classify the explainable evaluation functions \(\textrm{Imp}(\cdot )\) into three categories: filter-based evaluation function \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{w}_{i,j})\), feature map-based evaluation function \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{F}_{i,j})\), and activation map-based evaluation function \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{A}_{i,j})\). The larger of \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{w}_{i,j})\) implies that the filter plays a more significant role in the reference process. Likewise, the larger \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{F}_{i,j})\) or \(\textrm{Imp}(\varvec{A}_{i,j})\) is, the more important the corresponding filter \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\) is.

Filter-based

-

\(l_2\) Norm of Filter Weight

It’s most intuitive to directly evaluate the importance based on the filter’s weight parameters. We define that

where \(|\varvec{w}_{i,j}|\) denotes the modulus of set obtained by \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\) vectorization.

-

Taylor Expansion of Loss Function

The extent of a filter’s contribution is indirectly determined by calculating the change of loss function \(\mathcal {L}(D \mid W)\) before and after removing this filter from DCNN. A large change in the loss function signifies that this filter is of high importance. To reduce the computational complexity, we utilize the first-order Taylor expansion of the loss function to approximate it. Thus, we get the approximation importance of each filter only by computing the gradient of \(\mathcal {L}(D \mid W)\) once. The criterion for calculation is

where \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}=\varvec{0}\) indicates that the filter \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\) is removed, \(R_1\left( \varvec{w}_{i,j}\right)\) is the remainder term, negligible.

Feature map-based

-

Information Bottleneck Value

Motivated by the Information Bottleneck(IB) principle37, we calculate the information bottleneck value of the feature map \(\varvec{F}_{i,j}\), i.e.,

where \(\mathbb {I}(\cdot \hspace{5.0pt}; \hspace{5.0pt}\cdot )\) is mutual information, and \(\beta \in [0,1]\) is a balancing factor for the trade-off between information compression and information retention. For simplicity, we use Information Gain (IG), derived from information entropy \(\mathbb {H}(\cdot )\), to estimate mutual information, i.e.,

-

\(\gamma\) of Batch Normalization

Batch Normalization layers are typically inserted immediately after the convolution layer but before the activation layer. It ensures that the inputs to the activation functions have a more stable distribution. Assume \(z_\textrm{in}\) and \(z_\textrm{out}\) are the input and output of the Batch Normalization(BN) layer. The BN layer performs the following transformation:

where \(\mathbb {E}[z_\textrm{in}]\) and \(\operatorname {Var}[z_\textrm{in}]\) are the mean and the variance of the input, and \(\epsilon\) is a small constant to avoid division by zero. We refer to the channel importance evaluation criterion proposed by Liu et al.31 and define the importance of \(\varvec{F}_{i,j}\) as

If \(\gamma\) is close to 0, it means that \(\varvec{F}_{i,j}\) has significantly been reduced in scale. On the contrary, the large \(\gamma\) means \(\varvec{F}_{i,j}\) is enlarged in scale, which indicates that the influence on feature learning and information transfer is more significant.

-

Gradient

The gradient of the loss function with respect to the feature map reflects the extent to which small perturbations in \(\varvec{F}_{i,j}\) affect prediction loss. We define that

Activation map-based

-

Average Percentage of Positive

This study refers to the Average Percentage of Zeros (APoZ) criterion proposed by Hu et al.38, and infers that the average percentage of positive value in the activation map \(\varvec{A}_{i,j}\) can evaluate the corresponding filter \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\)’s importance, i.e.,

where \(\mathbb {I}(\cdot )\) is indicator function. The larger \(\mathrm{Imp_{APoP}}(\varvec{A}_{i,j})\) means the more important filter \(\varvec{w}_{i,j}\).

Network pruning

As shown in Fig. 1, we explore the DCNN pruning strategy based on multi-agent reinforcement learning QMIX. The interaction process between agents and environment is described by a Markov Decision Process(MDP), i.e., a tuple \((\mathcal {S},\mathcal {A}, P, R,\gamma )\), which indicates the state space, the action space, the rewards, the state-transition probability matric, and the penalization factors, respectively. Here, it illustrates the first four elements within the tuple in detail.

-

State Representation

At time step t, the global state of the environment notes \(s_t=\{s_t^1,s_t^2,\ldots ,s_t^L \}\), where \(s_t^i\) is the state of agent i, which is also the state of the i-th convolutional layer. We characterize the state \(s_t^i\) with six features:

where \(n_i\) is the number of filters in the i-th layer, which is also the input channel of the \((i+1)\)-th layer. \(n_{i-1}\) is the input channel of the i-th layer, which is also the number of filters in the \((i-1)\)-th layer. \(\mathrm{Kernel\_{size}}_i\) is the kernel size and \(\mathrm{Mean\_{weight}}_i\) is the mean of weight. \(\textrm{FLOPs}_i\) and \(\textrm{Params}_i\) denote the Floating-point Operations(FLOPs) and the Parameters(Params) of the i-th convolutional layer, respectively.

-

Action Space

In our research, each agent corresponds to a single convolutional layer within the neural network, with its action defined as the pruning rate applied to that layer, represented by a simple numerical value. To facilitate precise control over the pruning process, we establish the action space as a discrete set of possible pruning rates, where \(\mathcal {A}=[0\%,5\%,10\%,15\%,20\%]\). At time step \(t\), the collective action across all layers is represented as \(a_t = \{a_t^1, a_t^2, \ldots , a_t^L\}\), where \(a_t^i\) indicates the pruning rate selected for the \(i\)-th convolutional layer from the predefined set.

These pruning rates are not static and can evolve throughout the reinforcement learning process. The ultimate goal is to iteratively fine-tune these rates to achieve a targeted overall pruning level \(B\) for the entire deep convolutional neural network (DCNN). This tuning is done with the dual goals of minimizing the network’s prediction error and optimizing its performance, ensuring that the pruned model remains both efficient and accurate.

-

State Transition

At time step t, agent i receives the current state \(s_t^i\) of the i-th convolutional layer. Firstly, the importance scores of all filters are evaluated and sorted. Then, agent i prunes the filters with lower importance according to the current action \(a_t^i\), which is output by agent network i. Notably, all agents perform this pruning process simultaneously. Finally, we fine-tune the pruned network and receive the global state of the environment \(s_{t+1}\). The above process describes a state transition in the environment, as shown in the upper part of Fig. 2a, which is repeated until the end of the episode.

-

Reward Function

Instant reward directly induces DCNN pruning toward optimality. Network pruning aims to minimize model performance drop while achieving the expected pruning rate. Therefore, we define instant reward as a linear combination of test accuracy change and network sparsity change, where the sparsity is the ratio of the total filters in the pruned network to the original network.

where \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\) are hyperparameters, \(\textrm{TestAcc}_t\) and \(\textrm{Sparsity}_t\) are prediction accuracy on the test dataset and network sparsity at time step t, respectively. In addition, the total return of an episode is the cumulative of instant rewards.

-

Loss Function

The MDP provides a mathematical framework for DCNN pruning. We solve the above MDP problem based on the QMIX algorithm, as shown in Fig. 2b. The QMIX architecture comprises \(L\) agent networks alongside a mixing network. Each agent \(i\) is equipped with its own agent network, which represents the state-action value function \(Q_i(\tau ^i, a^i)\), where \(\tau\) signifies the joint action-observation history. The mixing network, a feed-forward neural network, takes the outputs from the agent networks as inputs and combines them in a monotonic manner to generate the total value \(Q_{\text {tot}}\). Specifically, \(Q_{\text {tot}}\) is calculated as follows:

where \(\mathcal {M}\) is the mixing function implemented by the mixing network. This function ensures that the combination of individual agent Q-values is monotonic and adheres to the problem’s constraints. s represents the global state, which is necessary for centralized training.

To train the QMIX model, we implement a Temporal-Difference loss function aimed at minimizing the discrepancy between the predicted Q-values and the target Q-values. The training is conducted in an end-to-end fashion to minimize the following loss function:

where b is the batch size of transitions sampled from buffer, \((\cdot )^{\prime }\) indicates the value of \((\cdot )\) at the next time step, \(\theta ^{-}\) are the parameter of target network.

Fine-tuning

The QMIX algorithm follows the CTDE training principle. After training it to convergence, each agent network makes decisions independently based on its own observations. Given the expected pruning rate, we prune the original pre-trained network according to the pruning strategy output from the trained QMIX’s agent networks. The pruned network undergoes a certain level of performance decline, reflecting degradation as a result of the pruning process.

To accelerate the performance improvement of the pruned network, we design a model compression framework that integrates network pruning and knowledge distillation, as shown in Fig. 2c. Specifically, we set the original pre-trained network as T-Net and the pruned network as S-Net. Then fine-tuning the pruned network based on knowledge distillation.

On the one hand, to guide S-Net to more fully learn the generalization ability of T-Net, we introduce label probability distributions with a temperature parameter T,

Compute the label probability distribution of S-Net and T-Net for \(T=t(t>1)\), respectively. We define the cross-entropy loss between two distributions as the distillation loss,

where \(z_t\) and \(z_s\) are the fully connected layer outputs of T-Net and S-Net, respectively, and \(p_i\) denotes the probability of the i-th label. On the other hand, S-Net needs to learn not only the knowledge from T-Net but also the ground truth. We define the cross-entropy loss between label probability distributions for \(T=1\) and the ground truth as the student loss,

With the above discussion, the optimization objective of fine-tuning the pruned network based on KD is a linear combination of the distillation loss and the student loss,

where \(\alpha\) is a hyperparameter that controls the weights of the two losses.

In summary, Algorithm 1 describes the process of automatic filter pruning based on QMIX.

Experiments

Experimental settings

To demonstrate the efficiency of our proposed method QMIX_FP, we experiment on the classical deep convolutional neural networks VGG-1639 and AlexNet1. VGG-16 consists of 13 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers. The filters are distributed as 64, 64, 128, 128, 256, 256, 256, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512, 512. AlexNet consists of 5 convolutional layers and 3 fully connected layers. The filter distribution is 64, 192, 384, 256, 256. We test their performance over CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets40 to further evaluate network pruning effectiveness.

In our experimental setting, we adopt widely used metrics to evaluate the network pruning effectiveness, including prediction accuracy, the number of filters, Parameters(Params), and Floating-point Operations(FLOPs). Notably, we set the prediction accuracy to be task-specific, i.e., top-1 accuracy on CIFAR-10 and top-5 accuracy on CIFAR-100.

For the original pre-trained DCNNs, we set the batch size as 128 and updated the network with the stochastic gradient descent algorithm, training for 200 epochs. The initial learning rate is 0.1, the decay rate is 1e-4, and the momentum is 0.9. For network pruning based on QMIX, we set that the discounted return is 0.99, and the \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\) in the reward function are 0.7 and 0.3, respectively. Moreover, the QMIX training optimizer is Adam, the learning rate is 0.01, the Buffer size is 512, the max episode is 500, and the max time step is 20 in an episode. The target network updates its parameters every 5 time steps. For network fine-tuning, we set the T in distillation loss as 2.5, the coefficient of distillation loss \(\alpha\) as 0.3, and training epochs as 100.

Results and analysis

We first conducted experimental analysis on the pruning result of VGG-16 on the benchmark dataset CIFAR-10. To further verify the robustness of our approach QMIX_FP, we successively replaced the DCNN with AlexNet and replaced the dataset with the more complex CIFAR-100, performing network pruning and analyzing results.

VGG-16 + CIFAR-10

To thoroughly investigate the performance and stability of the QMIX_FP under different target pruning rates, we set three expected pruning rates of 50%, 60%, and 70%, to observe the network compression results with various sparsity levels. Under the constraint of pruning rate, we prune VGG-16 with six filter importance evaluation functions, respectively. The results are shown in Table 1. The “Base” low is the metrics of the original pre-trained VGG-16. The “Acc. (pruned)” column shows the prediction accuracy of the pruned network. The “Acc. (fine-tuned)” column shows the fine-tuned prediction accuracy based on the knowledge distillation, and the data in square brackets shows the percentage of the prediction accuracy compared to the base. The “Filters” column indicates the number of filters. “M” denotes millions in the columns of FLOPs and Params columns.

Analyzing the prediction accuracy of the pruned network after fine-tuning, it’s shown that when the pruning rate is 50%, the pruned network maintains 99.60% of the original VGG-16 based on evaluation function \(\mathrm{Imp_{IB}}(\varvec{w}_{i,j})\), reaching the highest level. At a pruning rate of 60%, the pruned network maintains 98.73% of the original VGG-16, based on the average of the six importance evaluation methods. When the pruning rate climbs to 70%, the performance is 97.23% of the original. These results fully demonstrate the expected effect of network pruning, substantiating the efficacy of our proposed pruning method based on the QMIX algorithm and fine-tuning method based on knowledge distillation. Comparing six filter evaluation methods, we find that the pruned network obtained by the QMIX algorithm performs better only when evaluated based on the \(\gamma\) factor of the batch normalization layer. In contrast, it performs slightly less effectively when evaluated based on the APoP of the activation maps. What’s more, with the given pruning rate, the FLOPs and Params of the pruned network tend to be compressed by a larger amount. For example, when the pruning rate is 50%, the Params is compressed by about 77.50% based on evaluation function \(\mathrm{Imp_{Weight}}(\varvec{w}_{i,j})\); when the pruning rate is 60%, the FLOPs is compressed by about 76.65% based on evaluation function \(\mathrm{Imp_{Taylor}}(\varvec{w}_{i,j})\).

AlexNet + CIFAR-10

To verify that the network pruning applies to different DCNNs, we prune the pre-trained AlexNet and evaluate its performance on the benchmark dataset CIFAR-10. AlexNet’s architecture consists of five convolutional layers with a total of 1152 filters, resulting in fewer parameters and computations compared to VGG-16. We get a prediction accuracy of 0.8585 for the original pre-trained AlexNet on CIFAR-10, which is due to its lower complexity than VGG-16. The pruning result of AlexNet according to QMIX_FP is shown in Table 2, including indicators of changes in prediction accuracy and network structure parameters.

We observe that when the pruning rate of AlexNet is at 50% or 60%, the pruned networks’ prediction accuracy can maintain approximately 99.00% of the original accuracy. At the pruning rate of 70%, the network’s performance is slightly degraded, but it still manages to maintain over 95.49% of its original accuracy. In comparison, when the feature evaluation function depends on the information bottleneck value of the filter’s feature map, the pruned network suffers a greater loss of accuracy. Further, when the network pruning rates are 50%, 60%, and 70%, the pruned network’s Params are approximately 31.19%, 23.22%, and 15.46% of the original network, respectively. The AlexNet achieves a higher level of compression in both space complexity and time complexity, which satisfies the requirements in practical application scenarios. Thus, it can be seen that the QMIX_FP algorithm is not only applicable to high-complexity networks but also effective to small-scale DCNNs, which demonstrates its broad applicability in neural network architectures of different sizes.

VGG-16 + CIFAR-100

One metric for evaluating the effectiveness of network pruning is the prediction accuracy achieved on image classification datasets; hence, the dataset is also an influencing factor. We still perform network pruning on VGG-16 but evaluate its performance on the more complex CIFAR-100 dataset, where the prediction accuracy is measured using the top-5 accuracy. As shown in Table 3, we find the pruned network obtained by \(\mathrm{Imp_{IB}}(\varvec{F}_{i,j})\) is generally worse compared to other evaluation functions. Fine-tuning the pruned network through knowledge distillation can improve the prediction accuracy to 95.51% - 99.05% of the original pre-trained model. However, the model exhibits significant performance degradation under higher pruning rate constraints. The experimental results show that our algorithm QMIX_FP is still effective on the complex dataset CIFAR-100.

To intuitively judge the rationality of exploring the optimal pruning strategy via the multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm QMIX, we visualize the changes in the number of filters within each convolutional layer of VGG-16 and AlexNet both before and after pruning, as shown in Fig. 3. Figure a shows the filter number distribution of VGG-16 when the pruning rate is 50% where the evaluation function is \(\mathrm{Imp_{IB}}(\varvec{F}_{i,j})\). For the pruned network, the number of filters in each convolutional layer is 58, 64, 92, 128, 256, 256, 181, 109, 166, 247, 195, 116, 166. Figure b shows the filter number distribution of AlexNet when the pruning rate is 50% where the evaluation function is \(\mathrm{Imp_{Gradient}}(\varvec{F}_{i,j})\). After pruning, the number of filters in each convolutional layer is 56, 183, 133, 114, and 89. We find that the convolutional layers closer to the classifier have a higher proportion of redundant filters, which is also associated with the larger number of filters contained.

To demonstrate the advantages of our proposed method QMIX_FP, we compare our pruning results with the HRank41, HBFP42 and DDPG_FP19. Additionally, we compare the method employing a randomized evaluation criterion, i.e., the importance score of each filter is a random number. We adopt the same experimental setup as the baseline methods and focus on the pruning results of VGG-16 only.

-

HRank is an iterative filter pruning approach. The main idea is that low-rank feature maps contain less information, and the corresponding filters are considered relatively unimportant and can be pruned.

-

HBFP utilizes network training history for filter pruning iteratively. It prunes one redundant filter from each filter pair, ensuring minimal information loss during network training.

-

DDPG_FP is a filter-level pruning method based on Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), a single-agent reinforcement learning algorithm. The agent explores the pruning rate of one convolutional layer for each time step, and the pruned network is fine-tuned by retraining.

HRank and HBEP are traditional rule-based pruning methods, while DDPG_FP and our method QMIX_FP are automatic RL-based pruning methods. As shown in Table 4, the pruned network from RL-based methods exhibits lower model degradation than traditional methods. This is because the reinforcement learning algorithm can explore a larger pruning strategy space and continuously update the strategy according to reward feedback, effectively mitigating human subjectivity factors. Compared to DDPG_FP, QMIX_FP demonstrates more pronounced advantages on complex datasets, suggesting the robustness of the multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm. In summary, the drop in prediction accuracy of QMIX_FP is lower than that of other methods on both the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, which demonstrates the model’s stability.

Ablation study

We conduct ablation studies to analyze different components of the QMIX_FP further. This includes the QMIX algorithm for exploring optimal pruning strategy and the knowledge distillation technology for fine-tuning the pruned networks. Here, we report the results of VGG-16 on CIFAR-10 with prediction accuracy on the test dataset. Similar experimental conclusions can be identified in other deep convolutional neural networks and datasets.

Firstly, the contribution of the network pruning process based on QMIX is shown in Fig. 4. Our proposed pruning method is the “QMIX Prune,” while the “Iterative Prune” is a traditional rule-based pruning method. The horizontal axis in the figure represents the given pruning rate, and the vertical axis represents the test accuracy. The “Base” is the original prediction accuracy of the pre-trained network. Analyzing the model performance of the pruned network, we find that regardless of the pruning rate or the feature importance evaluate function, the test accuracy based on the QMIX prune method is higher than that of the traditional iterative prune method. Notably, the ordinary iterative method prunes a fixed number of filters, but the QMIX-based method tends to prune more filters than it. Here, the expected pruning rate is the criterion for determining whether an episode is terminated, whereas the real pruning rate is calculated based on a probability (action). It illustrates that the pruning strategy explored based on the QMIX algorithm is more effective as it prunes more filters while incurring smaller losses in test accuracy.

Secondly, the contribution of the fine-tuning process based on knowledge distillation is shown in Fig. 5. When the temperature parameter T is frozen to 0 in Sect. “Fine-tuning,” it means that the S-Net cannot learn the generalization performance of the T-Net and instead improves model performance only through training itself. To verify the effectiveness of knowledge distillation, we compare our experimental results with the case of \(T=0.\) The “Only S_Net” indicates fine-tuning the pruned network by retraining, while “S_Net with KD” is ours in the figure. The horizontal axis represents the training epoch, and the vertical axis represents the test accuracy. It shows that the fine-tuning method based on knowledge distillation converges faster and achieves a test accuracy approximately 1% higher at convergence compared to the retraining-based method.

Conclusions

We propose an automatic filter pruning approach grounded in reinforcement learning, distinct from conventional rule-based or single-agent reinforcement learning-based approaches. Our method, termed QMIX_FP, leverages the multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm QMIX to discover the optimal pruning strategy autonomously. This innovation not only streamlines the pruning process but also enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of DCNNs across various applications.

The efficacy of the proposed method was validated by applying it to VGG-16 and AlexNet on the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, achieving superior performance across multiple benchmarks. QMIX_FP stands out as a versatile framework for network pruning, adaptable to a wide range of DCNN architectures and datasets. Its flexibility lies in the ease of adjusting the number of agents and state transition functions to align with the specific structural characteristics of the network in question.

The societal impact of QMIX_FP is significant, particularly in resource-constrained environments such as mobile devices and edge computing platforms. By enabling more efficient and compact neural network models, our method contributes to the advancement of technologies that require real-time processing and minimal power consumption. This is particularly relevant for applications in healthcare, autonomous driving, and environmental monitoring, where the deployment of sophisticated AI models on portable or embedded systems can lead to advances.

Furthermore, our work builds on and complements existing research, such as MR-DCAE43, which uses manifold regularization in deep convolutional autoencoders for unauthorized broadcast identification and a real-time constellation image classification method for wireless communication signals based on the lightweight MobileViT network44. These studies highlight the growing trend of integrating advanced machine-learning techniques with specific domain knowledge to solve complex real-world problems. In line with this trend, future research directions for QMIX_FP include exploring the integration of reinforcement learning with other model compression techniques, such as parameter quantization and low-rank decomposition. In particular, we aim to investigate the optimal quantization precision for different convolutional features, using the QMIX algorithm to address mixed-precision parameter quantization challenges. Through these efforts, we aim to further improve the practical applicability and efficiency of neural network models in various fields.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study can be accessed at https://www.cs.toronto.edu/ kriz/cifar.html or are available on reasonable request from X. Z. (zuoxiaojinger@163.com).

Change history

23 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98325-0

References

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Altaheri, H., Muhammad, G. & Alsulaiman, M. Dynamic convolution with multilevel attention for EGG-based motor imagery decoding. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 18579–18588 (2023).

Li, J., Li, Y. & Du, M. Comparative study of EGG motor imagery classification based on dscnn and elm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 84, 104750 (2023).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3431–3440 (2015).

Liu, W. et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, 21–37 (2016).

Sun, J., Li, C., Wang, Z. & Wang, Y. A memristive fully connect neural network and application of medical image encryption based on central diffusion algorithm. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. (2023).

Gehring, J., Auli, M., Grangier, D., Yarats, D. & Dauphin, Y. N. Convolutional sequence to sequence learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 1243–1252 (2017).

Sun, J., Zhai, Y., Liu, P. & Wang, Y. Memristor-based neural network circuit of associative memory with overshadowing and emotion congruent effect. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 1–13 (2024).

Sun, J., Yue, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Memristor-based operant conditioning neural network with blocking and competition effects. IEEE Trans. Indus. Inform. 20, 10209–10218 (2024).

Abdel-Hamid, O. et al. Convolutional neural networks for speech recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Language Process. 22, 1533–1545 (2014).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Achiam, J. et al. Gpt-4 Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

He, Y. & Xiao, L. Structured pruning for deep convolutional neural networks: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 46, 2900–2919 (2023).

Vadera, S. & Ameen, S. Methods for pruning deep neural networks. IEEE Access 10, 63280–63300 (2022).

Ding, C. et al. Structured weight matrices-based hardware accelerators in deep neural networks: FPGAs and ASICs. In Proceedings of the 2018 on Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI, 353–358 (2018).

Kim, N. J. & Kim, H. Fp-agl: Filter pruning with adaptive gradient learning for accelerating deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 25, 5279–5290 (2023).

He, Y. et al. AMC: Automl for model compression and acceleration on mobile devices. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision 11211, 815–832 (2018).

Feng, Y., Huang, C., Wang, L., Luo, X. & Li, Q. A novel filter-level deep convolutional neural network pruning method based on deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Sci. 12, 11414 (2022).

Gupta, M., Aravindan, S., Kalisz, A., Chandrasekhar, V. & Jie, L. Learning to prune deep neural networks via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.04756 (2020).

Rashid, T. et al. Monotonic value function factorisation for deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 4295–4304 (2018).

Hinton, G. et al. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. Comput. Sci. 14, 38–39 (2015).

Bencsik, B. & Szemenyei, M. Efficient neural network pruning using model-based reinforcement learning. In 2022 International Symposium on Measurement and Control in Robotics (ISMCR), 1–8 (2022).

Kuang, J., Shao, M., Wang, R., Zuo, W. & Ding, W. Network pruning via probing the importance of filters. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 13, 2403–2414 (2022).

Han, S., Pool, J., Tran, J. & Dally, W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 28, 1135–1143 (2015).

Han, S., Mao, H. & Dally, W. J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and huffman coding. Int. Conf. Learning Represent. 56, 3–7 (2016).

Yang, T.-J., Chen, Y.-H. & Sze, V. Designing energy-efficient convolutional neural networks using energy-aware pruning. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 6071–6079 (2017).

Sanh, V., Wolf, T. & Rush, A. Movement pruning: Adaptive sparsity by fine-tuning. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 33, 20378–20389 (2020).

He, Y., Zhang, X. & Sun, J. Channel pruning for accelerating very deep neural networks. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 1389–1397 (2017).

Li, H., Kadav, A., Durdanovic, I., Samet, H. & Graf, H. P. Pruning filters for efficient convnets. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Liu, Z. et al. Learning efficient convolutional networks through network slimming. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 2736–2744 (2017).

Zhuang, T. et al. Neuron-level structured pruning using polarization regularizer. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 33, 9865–9877 (2020).

Sarvani, C., Ghorai, M., Dubey, S. R. & Basha, S. S. Hrel: Filter pruning based on high relevance between activation maps and class labels. Neural Netw. 147, 186–197 (2022).

Li, G. et al. Optimizing deep neural networks on intelligent edge accelerators via flexible-rate filter pruning. J. Syst. Architect. 124, 102431 (2022).

Camci, E., Gupta, M., Wu, M. & Lin, J. Qlp: Deep q-learning for pruning deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 6488–6501 (2022).

Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning (Lulu. com, 2022), 2 edn.

Tishby, N., Pereira, F. C. & Bialek, W. The information bottleneck method. Clin. Orthop. Related Res. physics/0004057, 368–377 (2000).

Hu, H., Peng, R., Tai, Y.-W. & Tang, C.-K. Network trimming: A data-driven neuron pruning approach towards efficient deep architectures. arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.03250 (2016).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2014).

Krizhevsky, A. et al. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. Handb. Syst. Autoimmune Dis. 1, 32–35 (2009).

Lin, M. et al. Hrank: Filter pruning using high-rank feature map. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 1529–1538 (2020).

Basha, S. S., Farazuddin, M., Pulabaigari, V., Dubey, S. R. & Mukherjee, S. Deep model compression based on the training history. Neurocomputing 573, 127257 (2024).

Zheng, Q., Zhao, P., Zhang, D. & Wang, H. Mr-dcae: Manifold regularization-based deep convolutional autoencoder for unauthorized broadcasting identification. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 36, 7204–7238 (2021).

Zheng, Q. et al. A real-time constellation image classification method of wireless communication signals based on the lightweight network Mobilevit. Cogn. Neurodyn. 18, 659–671 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [61773020]. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the referees for their careful reading and insightful suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z. L. and X. Z. conceived and conducted the experiments. Y. S., D. L., and Z. X. supervised the experimental progress and provided project support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article: Zhemin Li and Xiaojing Zuo were incorrectly mentioned as equally contributing authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Zuo, X., Song, Y. et al. A multi-agent reinforcement learning based approach for automatic filter pruning. Sci Rep 14, 31193 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82562-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82562-w