Abstract

Gene expression profiling is of key importance in all domains of life sciences, as medicine, environment, and plants, for both basic and applied research. Despite the emergence of microarrays and high-throughput sequencing, qPCR remains a standard method for gene expression analyses, with its data normalization step being crucial for ensuring accuracy. Currently, the most widely used normalization method is based on the use of reference genes, assumed to be stably expressed across all experimental conditions. In the present study, we show that finding a stable combination of genes, regardless of their individual stability, outperforms standard reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization. A stable combination of genes consists of a fixed number of genes whose individual expression balance each other all along experimental conditions of interest. Moreover, the present study shows that such an optimal combination of genes can be found using a comprehensive database of RNA-Seq data. Indeed, assuming that such a comprehensive database contains accurate gene expression profiles, we can extract in silico, by the way of the mathematical variance calculation, a stable combination of genes that reflects in vivo stability. As a case study, this new method was developed using the tomato model plant, with corresponding RNA-Seq data from the TomExpress database. However, the method is potentially applicable to other organisms with available RNA-seq data. Our results demonstrate the superiority of the reported method over commonly used housekeeping genes or other stably expressed genes. We therefore recommend the use of our new method together with classic ones in order to always obtain the best reference genes for a given experimental design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (denoted qPCR) is a common and widespread technique of molecular biology for detecting and quantifying gene expression. qPCR has become the gold standard technique for nucleic acids quantification in many domains of life sciences, as medicine, environment, and plants, for both basic and applied research. Many biological applications rely on this gene quantification method, including clinical and veterinary diagnostics and food safety1. The technique consists of measuring gene expression by ways of mRNA copy numbers in a given biological sample after successive amplification cycles. Then, absolute or relative quantification is achieved by measuring, respectively, the initial mRNA amount or the fold change between two or more given biological conditions of interest. A major issue of qPCR is the bias induced by the unknown initial number of cells and nuclei contained in a sample, which depends, for instance, on cell size or ploidy levels2,3,4. Nevertheless, relative quantification circumvents the need for an accurate quantification of starting material5. For this purpose, the normalization of qPCR data by a reliable reference gene plays a crucial role in accurate qPCR data interpretation6.

For a given target gene and a given experimental design, a reliable reference gene for qPCR data normalization is characterized by the following criteria: its expression level is unaffected by experimental factors; its expression has minimal variability between tissues and physiological states of the considered organism; and it has a similar expression level, or threshold cycle, to the target gene7. Historically, these characteristics were attributed to the so-called housekeeping genes (HKGs) which are constitutive genes required within all cells of organisms to maintain basic cellular functions. Nevertheless, it has been well established that not all HKGs are stably expressed and reliable for all situations7. Moreover, it is also stated in the MIQE guidelines (Minimum Information for publication of Quantitative real-time PCR Experiments) that the utility of a reference gene must be experimentally validated for particular tissues or cell types and specific experimental designs6.

The selection of qPCR reference genes typically consists of two main steps: the identification of a small number of candidate genes, and their validation with qPCR measurements in the experimental conditions of interest6,7,8. The first step was historically tackled by choosing well-known HKGs, commonly assumed to be almost stably expressed. Then, with the advent of genomic approaches, stably expressed genes have been mined from gene expression microarray databases9,10 and, more recently, from RNA-Seq databases11,12,13. Criteria described in the previous literature, to mine stable genes, rely on the measure of statistical dispersions of in silico gene expression profiles, using their variances, coefficients of variation, expression ranges, etc. In our study, among a particular set of genes, we will focus on the lowest variance gene, denoted LVG, as does the RefGenes tool from Genevestigator14,15. The second step of reference gene selection, consisting in the validation of identified candidate genes, is usually carried out by ranking genes based on qPCR measures and appropriate methods which do not require reference genes. For this purpose, following the “best 3” rule, we used the three more cited validation programs: geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper7.

In this study, we show that a suitable combination of non-stable genes outperforms the common use of stable genes for qPCR data normalization. Moreover, we show that such a reliable combination of genes can be found in silico using a comprehensive database of publicly available RNA-Seq data. As a case study, we developed our methodology on the tomato model plant (Solanum lycopersicum) using the RNA-Seq data from TomExpress. As far as we know, TomExpress is the most comprehensive RNA-Seq database for this economically and scientifically important crop and model plant16. On the one hand, the experiment consisted, for a given target gene, to predict in silico stable genes and gene combinations, and then to validate them in vivo. On the other hand, the purpose was to compare the ranks of the introduced gene combinations with both classical HKGs and LVGs. The experiment has been repeated twelve times, with twelve target genes showing different expression levels.

Results

Mean-variance analysis of genes, housekeeping genes, and lowest variance genes

TomExpress v2018 contains the expression values of 35,292 tomato genes over a wide range of 394 biological conditions (see Materials and methods). In our study, we chose to measure the expressions of target genes in different organs, tissues, and fruit development stages: Stem, Leaf, Flower, and Fruit at Immature green stage (20 DPA), Mature green stage (35 DPA), Breaker stage, and Red stage (Breaker + 5 days) (see Materials and methods). Figure 1 represents standard deviations of the 35,292 genes as a function of their mean expressions, calculated on a subset of biological conditions mimicking our experimental design: 148 out of the 394 available conditions (see Materials and methods). Both mean and standard deviation of a given gene are indicators of its respective expression level and dispersion, over the considered conditions. Thus, Fig. 1 clearly shows that some classical HKGs, highlighted with colored symbols, do not have the lowest standard deviations among genes with almost the same mean expressions (see Materials and methods). As an example, Elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1a.3) has a much larger standard deviation than Importin beta (IMP-b) for a similar expression level. As another example, three different loci have been identified in the literature for the classical Actin HKG (named ACT.1, ACT.2, and ACT.3) but only two of them appear to be stably expressed in Fig. 1 (ACT.2 and ACT.3). Additionally, the nine genes identified in the literature as stably expressed, but not considered as classical HKGs (depicted with non-filled black symbols in Fig. 1) are not all stably expressed under the biological conditions used in this study. In other words, for many HKGs, over the considered conditions, we can find genes that are more stable with similar expression levels. Moreover, performing mean-variance plots for other condition subsets underlines the impact of these biological conditions on HKG stabilities (Supplemental Figure S1).

Mean-variance scatter plot of tomato gene expressions. Scatter plot of mean and standard deviation (in log10 scales) of each gene expression profile (grey dots) defined by a particular subset of biological conditions extracted from TomExpress and fitting the experimental design of our study: 148 out of the 394 available conditions. Symbols and colors represent classical HKGs, extracted from the literature related to Solanum lycopersicum (each color represents a particular gene family). The 12 target genes analyzed in our experiment are represented by black dots. The names of these 12 target genes are ordered according to their expression levels, from lower expression levels (bottom-left) to higher expression levels (top-right).

We then defined the low variance score, denoted LVS, of a given gene measured on given conditions, by the proportion of genes having a higher variance among all genes with the same mean expression (see Materials and methods). Consequently, a gene with a LVS equal to 1 is considered the most stable gene among genes with the same mean expression, while a gene with a LVS equal to zero represents the less stable gene. For instance, Fig. 1 shows that ACT.3 and TUB have similar expression levels, but the former has a LVS near 1, while the latter has a very poor LVS. Furthermore, for any given target gene, we can now define more precisely the lowest variance gene (LVG) as the gene displaying the same level of expression and having a LVS equal to 1 (see Materials and methods). Obviously, in Fig. 1 and Supplemental Figure S1, all LVGs correspond to genes at the low border of the mean-variance scatter plots. Figure 2 depicts a heatmap of the LVSs for classical HKGs across specific organs, tissues, and cultivars. This heatmap clearly demonstrates that the LVS of an HKG varies depending on the conditions of interest, suggesting that no single HKG can be universally applied across all experimental conditions for qPCR normalization. This result is obviously valid for any gene, whether it is a HKG or not: a LVS depends on the biological conditions of interest (Supplemental Figure S2).

The gene combination method

The gene combination method consists of finding k genes, for a fixed integer k, whose expressions balance each other across all conditions of interest. Practically, we propose to find an optimal combination of genes using an RNA-Seq dataset containing a wide range of conditions that approximate our conditions of interest. The pseudocode of the combination method, based on this RNA-Seq dataset, is described in Fig. 3 for an integer k = 3. The method relies on two main steps. In the first step, we calculate the mean expression of our target gene on the RNA-Seq dataset, and we extract the pool of N = 500 genes having the smallest mean expressions greater or equal to the target gene mean expression (Fig. 3, lines 1–3). The number N of genes was empirically set to 500 since N greater than 500 genes did not give better results (Supplemental Figure S3). In the second step of the method, we calculate all geometric and arithmetic profiles of k genes, named hereafter (geometric or arithmetic) k-genes, and we select the optimal set of k genes with regard to the two following criteria: a geometric k-genes with a mean expression greater or equal to the target gene mean expression and the lowest variance among all arithmetic k-genes (Fig. 3, lines 4–18). On the one hand, the mean criterion has been calculated on the geometric k-genes because it is known that the geometric mean of multiple internal control genes gives a more accurate normalization of qPCR data, and we then used it for our qPCR normalizations17. On the other hand, the variance criterion has been calculated on the arithmetic k-genes because the arithmetic mean is more representative of the true amount of mRNA of the k genes, thus avoiding selecting genes with extreme values. Finally, we observed that selecting a k-genes with a mean expression greater or equal to the target gene mean expression and with minimal variance, tends to select a k-genes with a mean expression very close to the target gene mean expression. This phenomenon can be explained by the positive correlation between the mean expression of a gene and its variance (Fig. 1). The optimal k-genes is thereafter denoted LVkG: LV2G, LV3G, and so on, depending on the number k of genes that are considered. We note here that a LV1G is simply a LVG.

Pseudocode of the gene combination method. In this case, k is set to 3 genes, the gene combination method relies on a triple loop aiming at selecting the optimal 3-genes among a set of N genes whose expressions are extracted from an RNA-Seq dataset containing a wide range of conditions that approximate our conditions of interest. The optimal 3-genes is then a 3-genes having a mean expression greater or equal to the target gene mean expression and a minimal variance.

The experiment: in silico prediction and in vivo validation

The experiment was divided into two main parts (Fig. 4, left and right panels). The first part, consisted in finding and ranking candidate genes in silico, using TomExpress, for a given target gene. The second part consisted in obtaining in vivo qPCR measurements of the expression profiles of these candidate genes, and ranking them according to the reported methods. Then, we compared both in silico and in vivo obtained ranks to assess the consistency of these two independent ranking methods, and to be able to conclude that in silico mined genes reflect in vivo reality. In order to validate our method for a wide range of gene expression levels, we selected twelve target genes distributed along the whole range of expression levels (Fig. 1).

Previous to the in silico mining of candidate genes for a given target gene, we selected biological conditions mimicking our experimental design, and filtered the whole gene set (Fig. 4, boxes a, b, c). Therefore, our experimental design led us to consider 148 of the 394 conditions available in TomExpress (29 from Stem, 33 from Leaf, 11 from Flower, and 75 from Fruit). Concerning genes, filters were applied according to their mean expressions and future constraints ascribed to primer design. Hence, we filtered out genes that were too weakly expressed, or for which primers specificity could not be guaranteed (see Materials and methods). This filter led us to consider 17,768 of the 35,292 genes available in TomExpress.

Once biological conditions and genes have been filtered, candidate genes were mined for each target gene with the three studied methods (Fig. 4, box d). For the HKG method, we extracted the three HKGs whose mean expressions were the nearest, in absolute distance, to the mean expression of the target gene (named HKG 1, HKG 2, and HKG 3). For the LVG method, we extracted the three genes having the lowest variances among genes having a mean expression greater than the target gene (named LVG 1, LVG 2, and LVG 3). For the combination method, we extracted the three best LV2Gs (named LV2G 1, LV2G 2, and LV2G 3) and the three best LV3Gs (named LV3G 1, LV3G 2, and LV3G 3). In addition, we also calculated the mean profiles from the three HKGs and from the three LVGs, with two and three genes, as it has been shown that using an average of a set of stable genes leads to more accurate and precise results6,17. We therefore obtained, for a given target gene, 20 in silico predicted reference genes. The R scripts and data used for mining these predicted reference genes for the EIL3 target gene, as an example, are provided in Supplemental file S1 (see Materials and methods).

Pipeline for selecting and ranking candidate genes. The pipeline carried out for each target gene is built as follows: in silico selection of candidate genes (boxes a, b, c, d) and in vivo qPCR expression measurements (boxes f, g, h) are followed by in silico and in vivo rankings (boxes e, i). The pseudocode aiming at mining LVkGs (box d) is detailed in Fig. 3. Blue and green boxes correspond respectively to the processes aiming at selecting and ranking candidate genes in silico (from TomExpress database expressions) and in vivo (from qPCR measurements). Comparison of the obtained independent rankings is shown by a grey double arrow.

Figure 5 illustrates, with the EIL3 target gene, the balance phenomenon of the combination method, differing from HKG and LVG methods, and leading to more stable expression profiles. Indeed, for the LV3G, color shaded surfaces (Fig. 5d) highlight the expression part of a gene above or below the associated arithmetic mean, showing that mined genes balance each other to maintain a more stable mean profile. Moreover, we can also see that the mean of the three mined HKGs (Fig. 5b) is less stable than the mean of the three mined LVGs (Fig. 5c) which is in turn less stable than the LV3G (Fig. 5d).

In silico profiles of predicted reference genes for EIL3. The four panels show gene expression profiles extracted from TomExpress by selecting conditions fitting our experimental design: Stem, Leaf, Flower, and Fruit (delimited by vertical dashed lines). Within each organ, expressions are ordered according to their developmental stages. (a) Expression profile of target gene EIL3. (b) Expression profiles of the three mined HKGs, and their geometric and arithmetic means (black dashed and solid lines). (c) Expression profiles of the three mined LVGs, and their geometric and arithmetic means (black dashed and solid lines). (d) Expression profile of the best LV3G, named LV3G 1 (black dashed line), and the three associated gene expression profiles and arithmetic mean (black solid line). Color shaded surfaces underline the expression part of a gene above or below the arithmetic mean. In panels b, c, and d, the orange box highlights conditions for which the balance phenomenon clearly generates a more stable profile of the LV3G.

Comparison of in silico and in vivo rankings

The objective of our experiment is the comparison, for each target gene, of in silico and in vivo rankings of the 20 predicted reference genes obtained from the TomExpress platform (Fig. 6 and Supplemental file S2). On the one hand, in silico ranking was carried out according to the variances of the 20 in silico expression profiles. On the other hand, in vivo ranking was carried out by using three standard methods devoted to the identification of the most stable genes among a set of candidate genes based on their qPCR expression data: geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper (see Materials and methods). In order to measure the correlation between in silico and in vivo rankings, the Spearman’s correlation coefficients have been calculated. Figure 6 shows that all 12 coefficients are positive, underlying that all pairs of rankings are quite homogeneous. Moreover, 8 out of the 12 target genes (67%) show in silico and in vivo rankings that are quite significantly correlated (p-value < 0.1).

Comparison of rankings. For each target gene, in silico and in vivo rankings of the 20 candidate genes are shown. A gradient color emphasizes ranks, from red color (rank 1) through white color (rank 10) to blue color (rank 20). For each target gene, the Spearman rank’s correlation coefficient is shown, together with the associated p-value. Significant p-values are highlighted in green (p-value < 0.1).

Beyond these global comparisons, our results show that LVkGs generally outperform LVGs, which in turn generally outperform HKGs (Fig. 7). These results obviously arise from the significant positive correlation between both in silico and in vivo ranks which implies that a stable combination of genes found in silico reflects in vivo stability. Among the 12 target genes, we can see that LVkGs, LVGs, and HKGs, have been ranked first respectively 6 times (50%), 4 times (33%), and 2 times (17%) (Fig. 7a and b). When adding the number of candidate genes that are ranked first, second, or third, we obtain quite comparable results for both LVkG and LVG methods: 19 LVkGs, 16 LVGs, and 4 HKGs (Fig. 7b). Moreover, a classical Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test shows that these counts are significantly different, with a p-value = 0.008 of the chisq.test R function, underlining at least quite similar results for both LVG and LVkG methods and significantly better results than the HKG method (Fig. 7b). In the same way, best LVkGs and LVGs are always ranked first, second, or third, except for one LVkG which is ranked at the sixth place (Fig. 7a). On the contrary, best HKGs have often lower ranks (Fig. 7a). Our results also show that some LVkGs (both LV2Gs and LV3Gs) were not well ranked (Fig. 7c). For instance, ranks of LV3Gs were more variable than those of means of the three LVGs. Such variable results could be related to the used database, through the number of used conditions, their closeness to real experimental conditions, or the expression level of the target gene (Fig. 7a). Also, we underline that the mean of the three LVGs seems to have the less variable rank.

Comparison of ranks. (a) Scatter plot showing, for each target gene, the rank of the best ranked gene for each studied method. Target genes are sorted by increasing mean expression values. Symbols of genes for which the qPCR normalized profiles are equal (equal Tuckey tests) are surrounded with black color. (b) Bar plot showing, for each studied method, the number of genes that have been ranked at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd positions (gold, silver, and bronze colors). (c) Boxplots of ranks for each type of reference gene, obtained with the twelve target genes.

Comparison of normalized expression profiles

For each target gene, three expression profiles have been calculated by normalizing raw qPCR measures with the best HKG, the best LVG, and the best LVkG (Fig. 8 and Supplemental file S3). For each profile, an ANOVA and a Tukey post-hoc test have been carried out to compare mean expressions for observed conditions (see Materials and methods). Results show that, for some target genes, two normalized profiles (from two different reference genes, or method) led to equal Tukey tests (Fig. 7a). For instance, for target gene NOR, the expression profiles obtained with HKG and LVG methods, respectively ranked first and second, led to equal Tukey tests: its expression level at Breaker stage was significantly higher than the expression level at Breaker + 5, and higher than all previous stages, which were not significantly different from each other (Fig. 8a). Considering these kinds of equalities, we can see that the number of reference genes that were ranked first for a given method and which normalized profile was different from the two other profiles were: 4 for the LVkG method (EXP1, EIL3, TAGL1, and IAA9), 2 for the LVG method (EIL4 and SAM3), and 1 for the HKG method (EIN2) (Fig. 7a). Regarding this result, the LVkG method seems to produce more both accurate and distinct profiles. For instance, for the EIL3 target gene, the expression value for the Stem condition was clearly significantly higher than the others, which is not the case for the two other methods (Fig. 8b).

Normalized gene expression profiles. Expression profiles of target genes (a) NOR and (b) EIL3, calculated from qPCR measures, normalized with the best candidate gene of each studied method. For each obtained profile, an ANOVA analysis and a Tukey post-hoc test have been carried out to compare their mean expressions: equal lowercase letters indicate non-significant differences with a confidence level equal to 95%.

The application software

The gene combination method has been implemented in a beta version of the TomExpress v21 platform: https://tomexpress.gbfwebtools.fr. The two inputs of this statistical tool are the selected target gene and the choice of biological conditions that best approximate the desired experimental design. The output of this application is a set of predicted reference genes: three HKGs, three LVGs, and the best LV3G. Together with these candidate genes, the TomExpress output contains their standard deviations and interactive graphs or their expression profiles. The use of this tool is described, for given target gene and conditions, in the Supplemental file S4.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a stable combination of non-stable genes outperforms the average of classical reference genes, both HKGs and LVGs, for qPCR data normalization. More precisely, a stable combination of genes consists of a set of genes whose individual expressions balance each other across experimental conditions of interest. This study also shows that such an optimal combination of genes can be found using a comprehensive database of publicly available RNA-Seq data. For this purpose, we assume that the used comprehensive database contains accurate gene expression profiles, which implies that we can extract in silico a stable combination of genes that reflects in vivo stability. As a case study, this new method has been developed with the tomato model plant, using the RNA-Seq database from the TomExpress platform16. In addition, our method aims at finding reference genes adapted to the experimental design, instead of looking for universal reference genes which are known to be unsuitable7.

Our experiment was carried out over 12 target genes observed in seven different organs, tissues, and fruit developmental stages. We show that in silico ranking of mined reference genes (based on the variances of TomExpress expression profiles) and in vivo ranking (based on classical methods applied on qPCR measures) lead to similar ranks: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were all positive, and 8 out of the 12 correlation tests were significant. Moreover, results show that our method outperforms LVG method which in turn outperforms HKG method. Indeed, among the 12 target genes, 6 LVkGs were ranked first (50%), 4 LVGs (33%), and 2 HKGs (17%).

The keystone and main limitation of our method is the database on which it relies and its dependence on the availability, quality, and comprehensiveness of RNA-Seq data. Additionally, biases in publicly available datasets, such as over-representation of certain tissues or conditions, may affect the accuracy of gene selection. Nonetheless, as a data-driven method, it benefits from the important amount of publicly available datasets. Indeed, over the last decade, transcriptomics has produced an exponentially growing amount of data, and then almost exhaustive databases for many living organisms18. Nonetheless, for species or experimental conditions where RNA-Seq data is scarce or incomplete, the ability to identify optimal reference genes is compromised. We also underline the need of appropriate preprocessing methods leading to reliable gene expression profiles, as sequence quality validation, suitable mapping and quantification, and accurate normalization16,19,20.

The method introduced here is conceptually close to the “Modern portfolio theory” aiming at optimizing asset selection to obtain a portfolio maximizing the expected return and minimizing financial risk21. Here, candidate genes clearly play the role of assets, and the optimal portfolio corresponds to the optimal combination of genes. Again, the idea is that some genes/assets are correlated and can thus be combined to closely satisfy a given criterion, being the minimization of the variability. The idea was also encountered in the method developed by Chervoneva et al. (2010) consisting in ranking mean profiles of all subsets of very few candidate genes (about 10) by calculating their variances22. In their study, the authors underlined an advantage of their approach in the presence of even modest, especially negative, correlations among the candidate genes.

Being developed with the tomato model plant, we think that this method could be used for any other living organism. Indeed, the hypothesis of gene expressions that balance each other all along experimental conditions of interest, is not specifically related to the plant tissues. Obviously, expanding this method to other plant and animal species will be crucial for demonstrating its broader applicability and utility in various biological systems. Future studies should test the approach, for instance, in different organisms with varying genome complexities and experimental designs.

A proper choice of reference genes consists of the three following steps: the identification of a few candidate genes, the validation of these candidate genes with qPCR measures in the experimental conditions, and the assessment of expression stability for the chosen genes in the final experiment6,7,8. Practically, we have shown that the first step can be enhanced by the use of the LVkG method. We then suggest users apply our method alongside both HKG and LVG methods to identify a relatively small set of candidate genes. More precisely, we would propose users to identify, for instance, the best LV3G, three LVGs, and three HKGs, and to use them for the validation step. This methodology obviously encompasses all three described methods, and outperforms each one.

Materials and methods

The TomExpress database

TomExpress is a web platform aiming at bringing together all available RNA-Seq data from tomato experiments (https://tomexpress.gbfwebtools.fr). This transcriptomic database, produced using both in-house and public Next-Generation Sequencing data, represents the first European database for tomato that assists the community in the identification of genes with suited patterns of expression. It provides the research community with a browser and integrated web tools for RNA-Seq data mining and visualization at the whole genome scale. The database is regularly updated with new projects covering gene expressions in new conditions. As of this writing, TomExpress v2018 covers 38 projects and 433 different conditions representing a total of 1201 reviewed and homogeneously described RNA-Seq samples, including different cultivars, organs, development stages, and environmental conditions.

Tomato HKGs

The whole set of 37 classical HKGs analyzed in this study has been extracted from a comprehensive collection of articles aiming at selecting internal control genes for qPCR studies from different tissues, development stages, treatments or stresses, all related to the tomato model23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33. All these studies resulted in the ranking of a few candidate genes (mainly HKGs and a few LVGs) using geNorm, NormFinder, BestKeeper, RefFinder, or CV methods34. Supplemental file S5 contains names and symbols of these candidate genes, their Solyc identifiers, the citation of the article from which they have been extracted from, and the names of the HKGs that have been selected from each study. If not present in the corresponding article, the Solyc identifiers were found by Standard Nucleotide BLAST35 of given primer sequences in Tomato genome assembly SL3.0 and annotation ITAG3.236.

Mean-variance scatter plot

Let \(\:{X}_{gc}\) the expression of a gene \(\:g\in\:\left\{1,\dots\:,G\right\}\) on a biological condition of interest \(\:c\in\:\left\{1,\dots\:,C\right\}\) extracted from an RNA-Seq database containing the expressions of \(\:G\) genes over more than \(\:C\) biological conditions, as for instance TomExpress. Let \(\:{X}_{g}\) the expression profile of gene \(\:g\). The mean-variance scatter plot in Fig. 1 represents mean expressions (x-axis) and standard deviations (y-axis) of all these gene expression profiles, that is

Calculation of the LVS and definition of a LVG

We define the low variance score (LVS) of a particular gene, in an RNA-Seq dataset of observed conditions of interest, as the proportion of genes having a higher variance among all genes with the same mean expression. In order to calculate the LVS of a gene, we consider the set of 100 genes having a mean expression closest to the mean of the considered gene, and we then calculate the proportion of genes having a higher variance than the considered gene. Practically, let the notations of the above paragraph, and \(\:m\) and \(\:{s}^{2}\) the mean and the variance of our considered gene. Let also \(\:{X}_{g}\) for \(\:g\in\:\{1,\dots\:,100\}\) the expression profiles of the 100 genes which means \(\:{m}_{g}\) are closest to \(\:m\). We then define the LVS of our considered gene as

The calculation of this indicator could be based on a few more or less than 100 genes. However, using too few genes will result in a highly variable estimator of the LVS, and using too many genes will lead to a biased estimator because of the possible asymmetry of the distribution of these genes around \(\:m\) due to the non-linearity of the variance on the mean37. Then, for a given expression level, we define a lowest variance gene (LVG) as a gene displaying the same mean expression level and having a LVS equal to 1.

Experimental design and plant material

Plants used in this study were Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom wild type. For sampling leaf and fruit, seeds were directly sown in soil and grown under standard culture chamber conditions with a cycle of 14 h light at 25 °C and 10 h dark at 20 °C. Leaf tissues were collected from 45 days old plants. Flowers were tagged at anthesis (the day at which a flower is fully opened) and fruit was collected at 20 and 35 DPA (days post-anthesis) for Immature green (IMG) and Mature green (MG) stages, respectively. Breaker stage (Br) was defined as the day of initiation of color change at the blossom end of the fruit, and the ripening stage was relative to days after breaker stage (Br + 5). Flowers at anthesis, stems and roots were sampled from two-month-old plants, cultured in a hydroponic system. Seeds were first sowed and grown in vitro for one month in a growth chamber (25/20 °C and 14/10 h photoperiod). Then seedlings were transferred to 4 L pots and irrigated with nutritive solutions (Flora Micro, Flora Gro, and Flora Bloom, from General Hydroponics Europe, Fleurance, France) until sampling. For each of these seven tissues and stages, four independent biological replicates were collected and directly frozen in liquid nitrogen.

RNA extraction and qPCR assays

Total RNA was isolated from plant materials according to the ReliaPrep RNA Tissue Miniprep System fibrous tissue protocol (ref. Z6011 - Promega Corporation, France) with minor modifications. To reduce the presence of mucilage, we added several up and down pipetting and centrifugation in the protocol steps prior to transfer the lysate in the Minicolumn. The DNAse treatment was performed at the end of the protocol using DNA-free Kit from Invitrogen (ref. AM1906 - Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; Madison, WI, USA). RNA concentration and purity was estimated with the NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), and the quality of extracted RNA was visualized with formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. Total RNA (1 µg) was retrotranscribed by the GoScript Reverse Transcription System (ref. A5000 - Promega Corporation, France) and cDNA was stored at − 20 °C until RT-qPCR analysis.

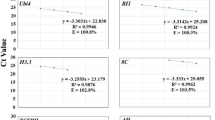

Real-time PCR reactions were performed using Takyon qPCR Kit (Eurogentec) and analyzed with an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Vector NTI Advance software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to design gene-specific primers. PCR products for each primer set were subjected to melt-curve analysis, confirming the presence of only one peak generated by the thermal denaturing protocol. In addition, qPCR amplification efficiency was checked. Three technical replicates were analyzed for each biological sample.

Filtering genes

Once candidate genes are mined in silico, from an RNA-Seq database, they will potentially be used as reference genes in qPCR experiments. As it is known, all genes are not suitable for such a purpose, and it is therefore necessary to filter them, and keep only the useful ones. For instance, a main constraint is that a robust candidate gene should have specific primer designs that avoid the amplification of undesired transcripts. For this purpose, genes have been filtered on their sequence identity by aligning them with each other in order to detect possible matches. The filtering has been processed in two steps (Supplemental file S1). We first made a local alignment using BLAST algorithm with the default e-value of 10. Then, in a second filtering step, using in-house script, we kept genes with sequence length greater than 100 bp that uniquely aligned to themselves. Also, genes having only one match with a query length minus a subject length greater than 100 bp have been kept. Finally, genes having a mean expression lower than 1 along biological conditions of interest have been discarded.

Validation of candidate genes: in vivo ranking

The most popular method, called geNorm, ranks candidate genes with respect to a gene stability measure M based on pairwise gene variations17. Three other methods, developed a few years later, are also widely used: NormFinder, BestKeeper, and the ΔCt method38,39,40. Chervoneva’s method consists in ranking mean profiles of all subsets for very few candidate genes (about 10) by calculating their variances based on the estimation of their unstructured covariance matrix22. For our purpose, following the “best 3” rule, we used three different validation programs7. More precisely, we used the three highly cited methods: geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper, with respectively 15,565, 5,411, and 3,774 citations, far ahead from ΔCt and Chervoneva’s methods with respectively 1177 and 73 citations (Web of Science, March 11, 2024). For each target gene, three rankings of the 20 candidate genes were then computed for the three chosen methods, and a synthetic ranking was carried out based on the geometric mean of these three ranks34,41. Practically, geNorm and NormFinder ranks were obtained with the NormqPCR R package, and BestKeeper ranks were obtained with the ctrlGene R package42,43. The R script achieving these rankings is given in Supplemental file S6 for EIL3 target gene. All the rankings obtained for the 12 target genes are shown in Supplemental file S2.

Normalized profiles of target genes

For each target gene, an ANOVA has been carried out with R on normalized Ct values, i.e. 2−ΔCt, with ΔCt equal to the difference between the Ct values of the target gene and the Ct values of the reference gene, according to studied stages (Stem, Leaf, Flower, IMG, MG, Br, and Br + 5). Mean differences of factor levels have been tested with Tuckey’s HSD method with a family-wise confidence level equal to 95%.

Code contents in Supplemental file S1 and Supplemental file S6

Supplemental file S1 contains homemade R scripts and data for calculations of HKGs, LVGs, and LVkGs, for the EIL3 target gene, as an example. The main R script is “script_1_refkGenes_pipeline”. First of all, this script imports gene expressions and metadata from TomExpress v18 (Fig. 4, box a), correspondences between identifiers of Solyc and Sly tomato annotations, and identifiers and symbols of classical HKGs. Next, the script extracts the conditions of interest (Fig. 4, box b) and filters genes according to previous paragraph “Filtering genes” (Fig. 4, box c). Then, the script extracts HKGs for the EIL3 target gene, and calculates LVGs and LVkGs (Fig. 4, box d). Finally, all 20 candidate reference genes are ranked according to their variances (Fig. 4, box e). The script “script_2_refkGenes_function” containing calculations of LVGs and LVkGs (Fig. 4, box d) is called by the main script. The pseudocode of script “script_2_refkGenes_function” is detailed in Fig. 3.

Supplemental file S6 contains a homemade R script and data for the ranking of the 20 candidate reference genes of the EIL3 target gene, as an example. The main R script is “Script_Analysis_of_qPCR_results_EIL3”. The other data files are called by the main script. First, the main script imports both qPCR data and associated primer efficiencies of the EIL3 target gene, HKGs, LVGs, and LVkGs, and calculates the relative expressions of our 20 candidate reference genes (Fig. 4, box h). Then, the main script proceeds to the calculations of rankings of candidate reference genes with geNorm, NormFinder, bestKeeper methods, and a synthetic ranking, as described in previous paragraph “Validation of candidate genes: in vivo ranking” (Fig. 4, box i). Finally, the EIL3 target gene is normalized three times according to the best reference gene provided by each method, and ANOVAs are performed as described in the previous paragraph “Normalized profiles of target genes” to obtain Fig. 8b.

Data availability

Data and code are provided within the manuscript and supplementary files.

Change history

14 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-97543-w

References

Taylor, S. C., Nadeau, K., Abbasi, M., Lachance, C. & Nguyen, M. et J. Fenrich, « The Ultimate qPCR Experiment: Producing Publication Quality, Reproducible Data the First Time », Trends Biotechnol., vol. 37, no 7, pp. 761–774, juill. doi: (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.002

Bower, N. I., Moser, R. J., Hill, J. R. & Lehnert, S. A. « Universal reference method for real-time PCR gene expression analysis of preimplantation embryos », BioTechniques, vol. 42, no 2, pp. 199–206, févr. (2007).

Pirrello, J. et al. « Transcriptome profiling of sorted endoreduplicated nuclei from tomato fruits: how the global shift in expression ascribed to DNA ploidy influences RNA -Seq data normalization and interpretation », Plant J., vol. 93, no 2, pp. 387–398, janv. doi: (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13783

Taruttis, F. et al. « External calibration with Drosophila whole-cell spike-ins delivers absolute mRNA fold changes from human RNA-Seq and qPCR data », BioTechniques, vol. 62, no 2, pp. 53–61, 01., doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.2144/000114514

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. et « Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT Method », Methods, vol. 25, no 4, pp. 402–408, déc. doi: (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Bustin, S. A. et al. « The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments », Clin. Chem., vol. 55, no 4, pp. 611–622, avr. doi: (2009). https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797

Kozera, B. & Rapacz, M. et « Reference genes in real-time PCR », J. Appl. Genet., vol. 54, no 4, pp. 391–406, nov. doi: (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-013-0173-x

Derveaux, S., Vandesompele, J. & Hellemans, J. et « How to do successful gene expression analysis using real-time PCR », Methods, vol. 50, no 4, pp. 227–230, avr. doi: (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.11.001

Dekkers, B. J. W. et al. « Identification of Reference Genes for RT–qPCR Expression Analysis in Arabidopsis and Tomato Seeds », Plant Cell Physiol., vol. 53, no 1, pp. 28–37, janv. doi: (2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcr113

Müller, O. A. et al. « Genome-Wide Identification and Validation of Reference Genes in Infected Tomato Leaves for Quantitative RT-PCR Analyses », PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no 8, p. e0136499, août., doi: (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136499

Bowen, J. et al. « Selection of low-variance expressed Malus x domestica (apple) genes for use as quantitative PCR reference genes (housekeepers) », Tree Genet. Genomes, vol. 10, no 3, pp. 751–759, juin., doi: (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-014-0720-6

Cheng, Y. et al. « genome-wide identification and Evaluation of Reference Genes for Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis during Tomato Fruit Development ». Front. Plant. Sci. 8 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01440 (2017).

Hoang, V. L. T. et al. « RNA-seq reveals more consistent reference genes for gene expression studies in human non-melanoma skin cancers », PeerJ, vol. 5, p. e3631, août., doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3631

Hruz, T. et al. « RefGenes: identification of reliable and condition specific reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization ». BMC Genom. 12 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-156 (2011). no 1.

Hruz, T. et al. Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the Meta-Analysis of Transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinforma. 2008, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/420747 (2008).

Zouine, M. et al. nov., « TomExpress, a unified tomato RNA-Seq platform for visualization of expression data, clustering and correlation networks », Plant J., vol. 92, no 4, pp. 727–735, doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13711

Vandesompele, J. et al. « Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes », Genome Biol., vol. 3, no 7, p. research0034.1-research0034.11, (2002).

Kodama, Y., Shumway, M., Leinonen, R. & on behalf of the International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration. « the sequence read archive: explosive growth of sequencing data ». Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D54–D56. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr854 (2012). no D1.

Maza, E. « in Papyro comparison of TMM (edgeR), RLE (DESeq2), and MRN normalization methods for a simple two-conditions-without-replicates RNA-Seq Experimental Design ». Front. Genet. 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2016.00164 (sept. 2016).

Maza, E., Frasse, P., Senin, P., Bouzayen, M. & Zouine, M. et « Comparison of normalization methods for differential gene expression analysis in RNA-Seq experiments », Commun. Integr. Biol., vol. 6, no 6, nov. doi: (2013). https://doi.org/10.4161/cib.25849

Markowitz, H. « Portfolio Selection ». J. Finance. 7, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/2975974 (1952). no 1.

Chervoneva, I. et al. « selection of optimal reference genes for normalization in quantitative RT-PCR ». BMC Bioinform. 11, 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-253 (2010). no 1.

Choi, S. et al. sept., « Evaluation of internal control genes for quantitative realtime PCR analyses for studying fruit development of dwarf tomato cultivar ‘Micro-Tom’ », Plant Biotechnol., vol. 35, no 3, pp. 225–235, doi: (2018). https://doi.org/10.5511/plantbiotechnology.18.0525a

Expósito-Rodríguez, M., Borges, A. A., Borges-Pérez, A. & Pérez, J. A. et « Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process », BMC Plant Biol., vol. 8, p. 131, déc. doi: (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-8-131

Fuentes, A. et al. et « Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR in Solanum lycopersicum L. inoculated with the mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus irregularis », Plant Physiol. Biochem., vol. 101, pp. 124–131, avr. doi: (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.01.022

González-Aguilera, K. L., Saad, C. F., Montes, C. & Alves-Ferreira, R. A. M. De Folter, « selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies in Tomato Fruit of the genotype MT-Rg1 ». Front. Plant. Sci. 7 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01386 (2016).

Lacerda, A. L. M., Fonseca, L. N., Blawid, R., Boiteux, L. S. & Ribeiro, S. G. et A. C. M. Brasileiro, « Reference Gene Selection for qPCR Analysis in Tomato-Bipartite Begomovirus Interaction and Validation in Additional Tomato-Virus Pathosystems », PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no 8, p. e0136820, août doi: (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136820

Leelatanawit, R., Saetung, T., Phuengwas, S., Karoonuthaisiri, N. & Devahastin, S. et « Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in postharvest tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum) treated by continuous low-voltage direct current electricity to increase secondary metabolites », Int. J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 52, no 9, pp. 1942–1950, sept. doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijfs.13477

Løvdal, T. & Lillo, C. et « Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in tomato subjected to nitrogen, cold, and light stress », Anal. Biochem., vol. 387, no 2, pp. 238–242, avr. doi: (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.024

Mascia Tiziana, S., Elisa, G., Donato & Fabrizio et Cillo « Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction normalization in infected tomato plants », Mol. Plant Pathol., vol. 11, no 6, pp. 805–816, juill. doi: (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00646.x

Rezzonico Fabio, Nicot Philippe, C., Fahrentrapp & Johannes et « Expression of tomato reference genes using established primer sets: Stability across experimental set-ups », J. Phytopathol., vol. 166, no 2, pp. 123–128, nov. doi: (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/jph.12668

Song & Gao « Evaluation of the expression of internal control transcripts by real-time RT-PCR analysis during tomato flower abscission », Afr. J. Biotechnol., vol. 11, no 66, août doi: (2012). https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB12.931

Wieczorek, P. & Wrzesińska, B. et A. Obrępalska-Stęplowska, « Assessment of reference gene stability influenced by extremely divergent disease symptoms in Solanum lycopersicum L. », J. Virol. Methods, vol. 194, no 1, pp. 161–168, déc. doi: (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.08.010

Xie, F., Xiao, P., Chen, D., Xu, L., Zhang, B. & et « miRDeepFinder: a miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs ». Plant. Mol. Biol. 80, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-012-9885-2 (sept. 2012). no 1.

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., Lipman, D. J. & et « basic local alignment search tool ». J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (oct. 1990). no 3.

The Tomato Genome Consortium. doi: 7400, pp. 635–641, mai (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11119

Anders, S., Huber, W. & et « Differential expression analysis for sequence count data ». Genome Biol. 11, p. R106, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 (2010).

Andersen, C. L., Jensen, J. L. & Ørntoft, T. F. et « Normalization of Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR Data: A Model-Based Variance Estimation Approach to Identify Genes Suited for Normalization, Applied to Bladder and Colon Cancer Data Sets », Cancer Res., vol. 64, no 15, pp. 5245–5250, août doi: (2004). https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496

Pfaffl, M. W., Tichopad, A., Prgomet, C. & Neuvians, T. P. et « Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper – Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations », Biotechnol. Lett., vol. 26, no 6, pp. 509–515, mars doi: (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47

Silver, N., Best, S., Jiang, J., Thein, S. & et « selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR ». BMC Mol. Biol. 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2199-7-33 (2006). no 1.

Xie, F., Wang, J. & Zhang, B. et « RefFinder: a web-based tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes », Funct. Integr. Genomics, vol. 23, no 2, p. 125, juin doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-023-01055-7

Ambroise, V. et al. et « Selection of Appropriate Reference Genes for Gene Expression Analysis under Abiotic Stresses in Salix viminalis », Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 20, no 17, p. 4210, août doi: (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174210

Perkins, J. R., Dawes, J. M., McMahon, S. B., Bennett, D. L. & Orengo, C. Kohl, « ReadqPCR and NormqPCR: R packages for the reading, quality checking and normalisation of RT-qPCR quantification cycle (cq) data ». BMC Genom. 13, 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-13-296 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Clémentine Dumont and Alexandra Legendre for their technical support during all the experimental process: production of the plant material, organ harvesting, and RNA extraction and purification. Many thanks to Thibault Gillet for the analysis of qPCR data. Many thanks to Pierre Frasse for leading both the experimental process and the analysis of qPCR data.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union grant H2020 TomGEM 679796, the COST Action CA18210 RoxyCOST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology, “Oxygen sensing a novel mean for biology and technology of fruit quality”), the Labex TULIP ANR-10-LABX-41 (Laboratoire d’Excellence TULIP), the FRAIB (FR3450, Fédération de Recherche Agrobiosciences, Interactions et Biodiversité), and the Vitifungen project (Fondation Jean Poupelain) supported by OxyFruit ANR (ANR-23-CE20-0001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, CC, BvdR, JJG, MB, JP, and EM designed the experiment. EM performed the analyses. AD and GM designed and developed the “reference genes” tool. AD implemented it into the TomExpress platform. EM wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this article, Julien Pirrello was omitted from the Author list and the Supplementary information files were incorrectly indexed. Full information regarding the correction made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Djari, A., Madignier, G., Chervin, C. et al. A stable combination of non-stable genes outperforms standard reference genes for RT-qPCR data normalization. Sci Rep 14, 31278 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82651-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82651-w

This article is cited by

-

TUG1: a potential endogenous reference gene for long noncoding RNA quantification in blood-based studies

Biomarker Research (2025)