Abstract

This study explores the mechanical properties of geopolymer mortars incorporating ceramic and glass powders sourced from industrial waste. A Box-Behnken design was employed to assess the effects of ceramic waste powder (CWP) content, alkaline activator ratio, solution-to-binder (S: B) ratio, and oven curing duration on the mortar’s performance. Compressive strengths were measured at 3 and 28 days, and regression models were developed to predict these outcomes. The relationships between compressive strength, flexural strength, and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) were also analyzed. Microstructural and molecular changes were investigated using scanning electron microscopy and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. According to response surface methodology results, the maximum compressive strengths of 22.79 MPa at three days and 25 MPa at 28 days were achieved using a mix containing 85.8% CWP, a 1.02 sodium hydroxide (NH): sodium silicate (NS) ratio, a 0.647 S: B ratio, and a 12-h oven curing time. Optimal oven curing conditions resulted in 28-day compressive strength, flexural strength, and UPV values of 25.7 MPa, 5.62 MPa, and 5765 m/s, respectively.

.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cementitious concrete is the most widely used construction material globally, recognized for its reliability and versatility, and second only to water in terms of consumption. However, cement production, growing at an annual rate of 5% 1, has become a significant contributor to environmental concerns, ranking as the second-largest source of CO₂ emissions after automobiles 2,3,4. These emissions arise from processes such as mineral grinding, fossil fuel combustion, and the processing of raw materials in kilns, all of which have a lasting environmental impact 5,6. Moreover, cement kilns emit large quantities of nitrogen oxides (NOx), contributing to acid rain and exacerbating the greenhouse effect 7. Energy-intensive cement production and the extensive use of natural resources have heightened global environmental concerns 7,8,9. Consequently, there is increasing pressure from global environmental summits for the cement industry to transition from traditional Portland cement to more sustainable alternative binders that maintain favorable structural and durability characteristics 10,11.

Geopolymerization presents a promising alternative for sustainable construction materials, synthesizing geopolymer materials through specific chemical reactions involving inorganic molecules. Typically produced by activating solid aluminosilicates with alkali solutions, these materials commonly utilize natural resources such as kaolin and bentonite as sources 12. Geopolymer cement is widely recognized for its sustainability, primarily because it excludes Portland clinker from its formulation, potentially reducing the carbon footprint by up to 90%13. Moreover, any industrial by-product or waste containing sufficient amounts of silica (Si) and alumina (Al) can theoretically serve as source material for geopolymer production 7, enabling the recycling and reuse of industrial waste, reducing the need for raw materials, and addressing landfill disposal issues. The interaction of Si and Al with hydroxide ions (OH⁻) in the alkali solution contributes significantly to the strength of the final product 14. The availability of suitable industrial waste and advancements in processing and synthesis techniques highlight the potential of geopolymer processes in developing new, sustainable construction materials 12. Therefore, studying the mechanical properties, microstructure, durability, and limitations of geopolymer cement derived from waste materials is crucial to identifying research gaps.

Various waste materials have been explored for geopolymer production, including red mud, rice husk ash, mine tailings, coal bottom ash, catalyst residues, recycled glass waste, ceramic waste, palm oil fuel ash, and paper sludge ash 12. Research on geopolymer concrete has predominantly focused on fly ash-based binders due to their availability, low water demand, and high aluminosilicate content 15,16,17,18,19. However, the quality of fly ash depends on the type and quality of coal and the power plant’s performance 20. Moreover, with the global shift towards renewable energy sources, the future availability of fly ash is expected to decline, even as the demand for cement continues to rise 19.

In this context, ceramic waste powder (CWP) emerges as a viable alternative. Global ceramic tile production exceeds 10 million square meters annually, with 15–30% resulting in waste from grinding and polishing processes. This substantial waste is typically landfilled, leading to soil, water, and air pollution in surrounding areas 21,22. CWP, rich in Si and Al and exhibiting pozzolanic reactivity 23, is a suitable feedstock for geopolymer production. Although limited research has been conducted on CWP-based mortars or concrete, several studies have explored the potential of blending CWP with other aluminosilicate sources to achieve desirable geopolymer compositions. For example, Bhavsar and Panchal 21 demonstrated that CWP could replace 10–15% of fly ash in geopolymer concrete without compromising mechanical properties.

Similarly, Rashed et al.24 reported that partially replacing fly ash with ceramic waste powder (CWP) up to 40% enhanced the 28-day compressive strength by 20–43%. However, when CWP replaced metakaolin, a reduction in compressive strength was observed, attributed to the incomplete reactivity of CWP with alkaline activators and the combined effects of particle packing and binder phase content12. Huseien et al.25,26 investigated CWP-based mortars blended with fly ash and granulated blast furnace slag (GBFS), demonstrating satisfactory compressive strength, enhanced workability, and optimized setting times. Kaya 27,28 evaluated the mechanical characteristics of geopolymer mortar derived from the alkali activation of raw ceramic powder. In terms of optimization, an ideal mixture with a silicate modulus of 0.12 and a water-to-binder ratio of 0.425 yielded a flexural strength of 5.97 MPa and a compressive strength of 26.75 MPa. Incorporating micro-silica and micro-alumina further improved the compressive strength of the geopolymer paste based on raw ceramic powder, achieving nearly a three-fold enhancement compared to control samples 29.

Recycled glass powder (RGP), a rich source of silica derived from municipal solid waste, is another potential material for geopolymer production [11]. However, its reactivity in geopolymerization is limited by the lack of reactive alumina. To overcome this limitation, combining RGP with materials rich in alumina is recommended to promote the formation of a sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) network, which enhances compressive strength 29. For instance, Çelik et al.16 found that incorporating 10% RGP with 13 M NaOH resulted in an optimal sustainable fly ash-based concrete with desirable properties. Similarly, Safarzadeh et al.11 combined RGP with clay and metakaolin to produce a geopolymer mortar, though the compressive strength was lower than that of traditional cement mortar.

Despite these advancements, limited exploration has been conducted into the fabrication of CWP-based mortars using appropriate additives and the generation of technical data. In this research, the mechanical characteristics of geopolymer mortars incorporating CWP and RGP were investigated, focusing on how binder contents, alkaline activator ratios, S: B ratios, and oven curing times affect compressive strength, flexural strength, and UPV of the mortars. The significance of this research lies in addressing the growing concerns surrounding waste management by utilizing CWP and RGP as alternative raw materials in construction. This approach offers an eco-friendly solution that reduces the demand for traditional cement-based products known for their high energy consumption and environmental impact. By applying RSM and analyzing the microstructural and molecular properties of the geopolymer mortars, this study seeks to determine the optimal formulations and curing conditions that can enhance the performance of these sustainable building materials. The outcome may facilitate the development of mortars that are not only stronger but also cost-effective, thereby promoting environmental sustainability and advancing construction technologies.

Material and methods

Materials

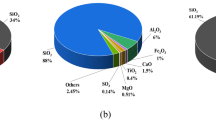

Ceramic waste powder (CWP) and recycled glass powder (RGP) were utilised as the primary components in the preparation of the geopolymer mortar. The CWP was collected from Firouzeh Tile Co. in Mashhad, Iran, and the RGP was obtained from a glass bead manufacturer in Arak, Iran. Both waste materials were ground to fine powders and sieved through a No. 200 sieve (75 μm) to achieve the desired particle size distribution. The physical properties of CWP and RGP are presented in Table 1, and their chemical compositions, determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF), are listed in Table 2. The particle size distribution (PSD) curves for CWP and RGP are shown in Fig. 1.

The SEM images of CWP and RGP, depicted in Fig. 2, reveal that both materials consist of irregular and angular particles, typical for waste-derived powders. The alkaline activator solution used in the geopolymer mortar consisted of a mixture of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃) solutions. The NaOH pellets, with a purity of 98%, were procured from DRM Chem, Iran. A 10 M NaOH solution was prepared by dissolving the appropriate amount of NaOH pellets in tap water and allowing the solution to cool for 24 h before use. The sodium silicate solution had a composition of 16.32% Na₂O, 32.75% SiO₂, and 50.93% H₂O by mass. Standard silica sand (Ottawa sand) was used as the fine aggregate following ASTM C349-18 30. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticiser (Sika ViscoCrete-3110 IR) was added to enhance the fresh mortar’s flowability. The superplasticiser has a 1.05–1.10 kg/L density and a freezing point of − 4 °C.

Mixing procedure and curing

The geopolymer mortar was prepared by first dry-mixing the sand, CWP, and RGP in a mechanical mixer for one minute to ensure homogeneity. The dry mixture was then activated by adding the alkaline activator solution (a mixture of NaOH and Na₂SiO₃ solutions) and mixing at moderate speed for an additional minute. Subsequently, the superplasticiser and extra water were added, and mixing continued for another minute to achieve the desired workability. The fresh mortar was then cast into moulds in two layers, with each layer being consolidated by vibrating for 10 s to eliminate entrapped air. The specimens were cured in an oven at 100 °C for 6, 9, 12, or 24 h. After a cooling period of 2 h following the designated curing time, the specimens were removed from the moulds. The demoulded samples were then stored at ambient room temperature until reaching a total curing duration of 3 or 28 days. The binder content for all geopolymer samples was fixed at 350 kg.m-3.

A control sample using 100% Portland cement (PC100) was also prepared for comparison with the geopolymer samples. The sand-to-solid and water-to-solid ratios for the PC100 control sample were fixed at 2.75 and 0.6, respectively. The mix proportioning and heat curing schedule of the prepared mortars is presented in Table 3.

Testing methods

The mechanical and physical properties of the geopolymer mortars were evaluated through compressive strength, flexural strength, and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) tests, with an average of three specimens reported for each test. Compressive strength tests were conducted on 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm cube specimens following ASTM C349-18 30, with the load applied at 150 kN/min until failure. Flexural strength and UPV tests were performed on 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm prism specimens following ASTM C348-21 31 and ASTM C597-09 32, respectively. The microstructure and surface morphology of selected mortar samples were SEM, and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) was employed to analyze the elemental composition. Samples aged 28 days were used for SEM analysis and were coated with a thin layer of gold to prevent charging during imaging. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed to identify the functional groups present in the mortar samples. For FTIR analysis, specimens were prepared by mixing powdered mortar with potassium bromide (KBr) and pressing the mixture at 295 MPa for 2 min. The spectra were recorded over a range of 400 to 4,000 cm⁻1.

Design of experiments

Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed using a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) implemented in Design-Expert software version 12.0.3.0 to optimize the experimental process and reduce the required tests. This design enabled the development of quadratic models to assess the interactions among the experimental factors, as expressed in Eq. (1) 33

where Xi and Xj are the variables, Y is the response, β0 is the intercept, while βi, βii, and βij represent the coefficients of the linear, quadratic, and interactive terms, respectively.

The factors and their corresponding levels used in the BBD are listed in Table 4. The factors included the percentage of CWP in the CWP/RGP binder (A), the NH: NS ratio (B), the S: B ratio (C), and the oven curing duration (D). These factor levels were determined based on preliminary experiments and adjusted to optimise the mortar properties. The required number of experiments is determined using Eq. (2) 34.

The total number of experiments required for the BBD was determined based on the number of factors and levels, resulting in 30 experimental runs, which included 24 factorial points and 6 centre points. The experimental design and corresponding response values, including the 3-day compressive strength (y1) and 28-day compressive strength (y2), are detailed in Table 5.

RSM was applied to estimate the effects of the variables on the responses. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to analyse and validate the regression models, facilitating the interpretation of the results. ANOVA assesses the relative significance of factors by evaluating their percentage contribution to the response variable. The analysis was performed at a 5% significance level, corresponding to a 95% confidence level. A p-value of less than 0.05 indicates that a factor significantly impacts the response, while a p-value of less than 0.01 suggests a highly significant effect.

Conversely, a p-value greater than 0.1 indicates that the factor is not statistically significant. The adequacy of the models was assessed using the coefficient of determination (R2) and adjusted R2 values. Numerical and graphical optimisation techniques provided by the Design-Expert software were applied to optimise the responses simultaneously. The desired goals for each variable and response were specified, with all variables kept within their respective ranges while the responses were maximised.

Results and discussion

Response surface analysis

Development of response models using RSM

The experimental design generated by the design expert software is presented in Table 5. Figure 3 compares the overall compressive strength results of these experiments with the control sample. The data reveal that the compressive strengths of the geopolymer mortars at both 3 and 28 days were nearly identical for each sample. Heat curing and high-molarity alkaline solutions accelerate geopolymerization, leading to high early compressive strength and similar strength values at the studied ages 13,35,36. At high curing temperatures, the dissolution of primary materials speeds up, resulting in faster reaction rates and extended synthesis of geopolymer precursors. Additionally, the higher the NaOH concentration, the more Na⁺ ions are available in the solution, which is crucial for geopolymerization due to their role in balancing charges and forming the alumina-silicate network 36,37.

Generally, the geopolymer mortars exhibited satisfactory compressive strengths compared to the control. Approximately 90% of the geopolymer mortars showed higher compressive strength at 3 days than the control sample, which had a compressive strength of 11 ± 1 MPa at the same age. Additionally, 20% of the samples demonstrated higher compressive strengths at both 3 and 28 days than the control. Notably, in 6.7% of the samples, the 3-day compressive strength of the geopolymer mortar surpassed the 28-day compressive strength of the control sample, which was 23 ± 1 MPa. These findings are significant for various reasons, particularly for early strength development and construction timelines. Improved early strength not only promotes quicker project advancement but also permits the application of stress on structures at an earlier stage. This facilitates the prompt removal of formwork and expedites subsequent construction phases, thereby enhancing the overall speed of project completion. These benefits are particularly advantageous for projects that require swift execution or have constrained curing periods, such as repair and renovation initiatives.

RSM indicates that the studied factors significantly influence the compressive strengths of CWP-based geopolymer mortars, including the percentage of CWP in the binder, the NH: NS ratio, the S: B ratio, and the oven duration. Table 5 shows variations in CWP percentages (80%, 90%, 100%) in the binder. Mortars with 90% CWP generally achieved optimal results, especially when combined with favourable conditions such as a balanced NH: NS ratio and sufficient curing time. For instance, samples with 80% CWP, such as C80N1S0.7O12, also demonstrated high compressive strengths (25.7 MPa at 28 days), indicating that a moderate reduction in CWP content, if balanced by other factors, can still produce strong results. Additionally, including RGP in the binder composition enhanced compressive strength, likely due to improved bonding between constituents during gel formation. This finding is consistent with previous studies 37, which observed similar improvements in compressive strength in calcium carbide-RGP-clay soil geopolymers.

The NH: NS ratios used were 1:1, 1:2, and 2:1. A 1:1 ratio frequently resulted in better compressive strengths. Combined with optimal S: B ratios and curing conditions, this ratio often produced compressive strengths above 20 Mpa, suggesting a balanced alkaline activator ratio is crucial for effective geopolymerization and strength development.

The S: B ratios of 0.5, 0.6, and 0.7 were also significant. A higher S: B ratio, particularly 0.7, often leads to higher compressive strengths, as seen in samples like C80N1S0.7O12, due to the enhanced availability of alkaline solutions, facilitating the geopolymerization process and strengthening the geopolymer matrix. Conversely, a lower S: B ratio of 0.5 was associated with weaker compressive strengths, typically below 15 MPa, suggesting insufficient alkaline activation. It underscores the importance of optimizing the S: B ratio to ensure adequate geopolymerization and mechanical strength. Oven curing duration also had a notable impact. Samples cured for 12 h, such as C90N1S0.6O12, frequently exhibited compressive strengths comparable to or exceeding those cured for 24 h, suggesting that 12 h of curing may be sufficient for optimal mechanical properties in certain mix designs, potentially providing a more efficient process without compromising strength.

Overall, several trends are evident across the samples. C90N1S0.6O12 and C80N1S0.7O12 consistently produced high compressive strengths, highlighting the synergistic effects of the S: B ratio, NH: NS ratio, and curing duration. These results emphasize the need to carefully balance these factors to achieve the desired performance in geopolymer mortars.

The experimental results were modelled to determine the most suitable polynomial function for the data. Different models were fitted non-linearly by applying model summary statistics, the sum of squared deviations, and fitting errors. The regression models for each response at two different oven durations are presented in Eqs. (3 to 6):

For 12-h oven duration:

For 24-h oven duration:

ANOVA results for the models are presented in Table 6. Both models yielded p-values below 0.0001, indicating that they are statistically significant and that the factors studied had a meaningful impact on compressive strength at both 3 and 28 days. When analyzing individual factors, Factor A (CWP percentage) showed a highly significant effect in the 3-day model, with a p-value of less than 0.0001 and an F-value of 27.15, indicating a strong influence on early compressive strength. However, in the 28-day model, the influence of this factor diminished (F = 1.61, p = 0.2213). This reduced impact over the curing period can be attributed to rapid geopolymerization reactions and subsequent microstructural changes. The reactions are more pronounced in the early stages, leading to a more significant contribution from CWP. Over time, as geopolymerization products mature and the microstructure evolves, the relative influence of CWP percentage on overall strength may be reduced due to other competing mechanisms becoming more dominant. This observation aligns with the findings reported by Mermerda et al.38.

Factor C (S: B ratio) exhibited the most substantial influence on compressive strength in both models, with extremely low p-values (< 0.0001) and very high F-values (409.73 for the 3-day model and 544.79 for the 28-day model), indicating that Factor C is a critical determinant of compressive strength at both stages. Specifically, the S: B ratio affects the efficiency of the alkali activation process, which is essential for fully activating the binder materials of the geopolymer and facilitating the formation of aluminosilicate gels. These gels provide the structural integrity of the geopolymer matrix, thereby influencing the compressive strength. This relationship emphasizes the necessity of the S: B ratio during the formulation of geopolymer mortars. Previous studies have also highlighted the essential role of this ratio in strength improvement 28,39. For instance, Shoaei et al. 23 reported that mortars based on CWP demonstrated increased density at elevated S: B ratios, attributed to higher liquid content and improved geopolymerization of the components, achieving optimal compressive strength at the S: B ratio of 0.6.

Factors B and D are also significant in both models, although they have less influence than Factor C. An evaluation of the interaction effects between various factors revealed significant findings. In the 3-day model, the interaction between Factors A and B was statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.0022. This means that the percentage of CWP in the geopolymer mortar significantly influences the 3-day compressive strength, contingent upon the alkali solution ratio. Consequently, at a certain level of CWP, the compressive strength may improve when paired with a higher or lower NH: NS ratio. To optimize the 3-day compressive strength, adjusting the alkali solution ratio while also varying the CWP content could be key.

Furthermore, significant interactions were observed between Factors B and C and Factors B and D, with p-values of less than 0.0003 and 0.0001, respectively. The interaction between Factors B and C indicates that if the S: B ratio is high, an adjustment of the NH: NS ratio is required to maintain an efficient geopolymerization process and prevent excess liquid from diluting the binder strength. Accordingly, neither factor alone can be adjusted without considering the effect of the other. This interaction is also predominant in the 28-day model, given the importance of Factor C.

However, in the 28-day model, another significant interaction is observed between Factors A and C. This interaction suggests that higher S: B ratios might dilute the effects of the CWP percentage, or there may be a threshold ratio where the benefits of adding CWP peak. Essentially, the amount of solution can either enhance or inhibit the strength contributed by the CWP, depending on the amount of binder used.

The quadratic terms (A2, B2, and C2) are all highly significant in both models, with p-values below 0.0001, indicating a nonlinear relationship between factors and compressive strength. This emphasizes the necessity of including quadratic terms to capture the complex behavior of the factors. The nonlinearity shows that the effects of these factors on compressive strength do not change at a constant rate. Initially, increases in these factors may enhance strength rapidly, after which further increases can either diminish or reverse this effect. A comprehensive understanding of these nonlinear relationships enhances the predictive accuracy of the compressive strength model across different conditions. Additionally, incorporating these complexities enables adaptability to actual environmental and curing conditions, ensuring better performance predictions, facilitating iterative research, and leading to more efficient and sustainable geopolymer formulations. Other researchers have also employed quadratic equations to predict the compressive strength of geopolymer products 40,41.

Model fitting was further supported by the lack-of-fit p-values, which exceeded 0.05 for both models, indicating a low likelihood of abnormal errors and confirming that the models fit the data well. The R2 is exceptionally high, 0.98 for the 3-day model and 0.9830 for the 28-day model, demonstrating a strong correlation between the predicted and actual compressive strengths. The adjusted R2 values are also close to the R2 values, suggesting that the models were appropriately fitted without excessive complexity. Moreover, the low coefficients of variation (CV%) of 4.22% for the 3-day model and 4.08% for the 28-day model indicate high precision and reliability in the predictions. Figures 4 and 5 display the regression analysis plots for compressive strengths. The normal plots of residuals indicate a linear distribution for both models, suggesting normal data distribution. The scatter diagrams in Fig. 5 show the predicted values closely matching the actual values, as evidenced by their proximity to the y = x line, confirming that the established models are well-fitted.

Factor affecting compressive strength

Response surface plots are valuable tools for analyzing the effects of various factors and their interactions on specified responses. The significance of a variable is more pronounced when the response surface shows greater curvature, indicating a strong impact, whereas minimal curvature suggests a lesser effect.

The results from Figs. 6 and 7 indicate that at constant S: B and NH: NS values, a slight increase in CWP content up to 84–88% enhanced the compressive strength of the geopolymer mortar, particularly in samples aged 3 days. This improvement is attributed to the presence of Al in CWP, which dissolves more readily than Si species, leading to the formation of Al-rich gels 42. Furthermore, when either NH: NS or CWP content was fixed individually, a higher S: B ratio significantly contributed to increased compressive strength, highlighting the critical role of the alkaline solution.

At constant S: B ratio, the mortars’ 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths initially increased and then decreased with higher NH: NS content. Peak compressive strengths were observed within NH: NS ranges of 0.5–1.1 for 3-day aged mortars and 0.7–1.2 for 28-day aged mortars. Since Si dissolves more slowly and with more difficulty than Al, sodium silicate compensates for this limitation by providing additional Si, thus accelerating the geopolymerization process. However, if the Si/Na molar ratio exceeds optimal levels, the alkali concentration diminishes, leading to the adsorption of Si onto solid particles and hindering the reaction 43.

Determination of factors’ optimal values

The numerical optimization feature of design expert software was employed to determine the optimal area of independent variables, aiming to maximize the mortar’s 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths simultaneously. The optimal conditions identified were a CWP content of 85.8%, an NH: NS ratio of 1.02, and an S: B ratio of 0.647, with an oven curing duration of 12 h. Under these conditions, the predicted maximum compressive strengths are 22.79 MPa for 3-day-aged mortars and 25 MPa for 28-day-aged mortars.

Figure 8 presents the graphical optimization conducted by considering the range of criteria specified in Table 4. The yellow region represents the adjustable range of factors necessary to meet the established conditions, including a 3-day compressive strength between 18 and 23 MPa and a 28-day compressive strength from 23 to 25.7 MPa. To satisfy these constraints simultaneously, the S: B ratio must exceed 0.59, while the NH: NS ratio should fall between 0.5 and 1.78. Furthermore, the CWP% needs to be maintained within the range of 80 to 96 to fulfill the conditions above.

These optimized parameter ranges not only highlight the potential of using industrial waste materials, such as CWP and RGP, in geopolymer production but also demonstrate a competitive performance compared to traditional cement-based mortars, which typically exhibit compressive strengths ranging from 20 to 28 MPa at 28 days. The high content of CWP contributes to the formation of cementitious compounds due to its pozzolanic nature as an aluminosilicate source. This observation aligns with previous studies 33 that have reported an enhancement in overall binder content and increased structural integrity of the product due to the incorporation of CWP. As a rich source of silica, RGP contributes to the development of a more durable network of aluminosilicate bonds, thereby strengthening the mortar’s structure 33. The synergistic effects of the S: B and the alkaline activator ratio enhance workability and provide sufficient activator concentration to initiate the geopolymerization reaction, leading to stronger bond formations and, consequently, elevated compressive strength. The optimal range identified falls within those reported in the literature33,44. Concerning Table 5, two mortar samples, C80N1S0.7O12 and C80N0.5S0.6O12, are identified as the closest to the optimal composition and compressive strength suggested by Fig. 8. Consequently, further investigations were conducted on these two samples.

Flexural strength test results

The flexural strengths of the geopolymer specimens at 28 days are illustrated in Fig. 9. The test was performed on half of the samples defined in Table 5, which had been oven-cured for 24 h.

While the flexural strength of the cement sample was higher than that of C90N2S0.5O24, the figures for most geopolymer samples surpassed that of the control sample. At constant oven duration, the flexural strength varied from 2.245 to 5.195 MPa, influenced by alterations in the mix design. The flexural strength results are almost in the range that was previously reported for CWP-based mortars 23,26. The highest values were obtained for C80N1S0.7O24, followed by C90N1S0.6O24.

Improvements in flexural strength were noticeable with increasing the S: B ratio, which corroborated the compressive strength results. Shoaei et al. 23 documented the beneficial influence of the S: B ratio on the flexural strength of the CWP-based mortars, while flexural strength reduction was observed during the production of natural pozzolan geopolymer 45. The appropriate S: B ratio is strongly influenced by the type of precursor.

Correlation of responses at fixed oven duration

Statistical correlation analysis is a widely used technique to assess the different mechanical and physical characteristics of mortars and concretes by examining various responses obtained from experimental tests. For this purpose, the flexural strength and UPV tests were carried out on the geopolymer samples cured in the oven for 24 h and then aged for 28 days. Figure 10 presents variations of compressive strength, flexural strength, and UPV results for the examined samples. All three test results follow similar trends; thus, their correlations were evaluated in detail.

Correlation between flexural and compressive strength

The results of the flexural strength against the compressive strength are given in Fig. 11. The best-fit Equation was obtained by a linear trendline with a high correlation coefficient of 0.997. Therefore, the developed formula will help predict the flexural strength of geopolymer mortars based on their compressive strength.

Generally, the relationship between geopolymer products’ compressive and flexural strengths is more complex than cement-based products. This complexity is due to several factors, including the precursor materials, mix design, curing conditions, and the type and concentration of the alkaline solution 46. Table 7 depicts the prediction formulas for flexural strength corresponding to the compressive strength from previous literature for various geopolymer mortars and concretes. According to the mentioned factors, different linear and nonlinear equations have been proposed for the defined strength range. Hardjasaputra et al. 47 collected 134 data points to investigate the correlation between compressive strength and flexural strength of geopolymer concrete. They confirmed that the data followed a similar trendline to that obtained by other researchers 46,48. Accordingly, in the present study, the experimental data have been fitted to the most popular model of Fs = 0.5 Cs0.7. As shown in Fig. 11, experimental values of flexural strength of the geopolymer mortars aligned closely with the values derived by the model, with a high correlation coefficient of 0.968.

Correlation between compressive strength and UPV

The UPV test propagates an ultrasonic pulse through the specimen and measures the time the pulse travels through the sample. This nondestructive test evaluates the internal structure of the specimen by detecting material discontinuities or defects such as cracks, voids, and damages. A higher UPV indicates greater integrity and quality of the geopolymer mixes 49. Figure 10 shows the UPV results of CWP-RGP mortars ranging from 3300 to 5200 m/s, slightly higher than the UPV values of geopolymer mortars made with glass aggregate 50 and ash 51. However, the UPV values of the CWP-RGP mortars are significantly higher than those reported for metakaolin-based specimens 52,53.

Among the investigated samples, C80N1S0.7O24 exhibits the highest UPV value, while C90N2S0.5O24 exhibits the lowest. The results are directly proportional to the samples’ compressive strengths due to the effect of porosity, air void network, and the quality of the mortar structure on the ultrasonic wave transmission. Figure 12 illustrates the correlation between the compressive strength and UPV experimental values. The R2 of 0.9422 indicates a strong linear relationship between UPV and compressive strength. It is worth noting that some researchers have reported a linear relationship between these properties 50,56,58,59,60, and the model proposed by Choi et al. 60 is almost consistent with the final Equation obtained in this research.

Effect of the oven duration on optimal mix designs

Figure 13 shows the variations in compressive strength over different oven curing periods for the optimal mix designs C80N1S0.7 and C80N0.5S0.6. Without heat curing, the 28-day compressive strengths were significantly higher than the 3-day strengths, suggesting that geopolymerization progressed at a slower rate at ambient temperature. Additionally, prolonged heat exposure notably increased the 28-day compressive strengths. A similar trend was observed for mortars subjected to a 6-h oven heating period, indicating that insufficient heat was provided to complete the geopolymerization reaction at earlier ages, resulting in a slower reaction progression until later stages 61.

Significant improvements in both 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths were observed as the oven curing duration increased from 6 to 9 h to 12 h. Moreover, the gap between the 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths of the mortars narrowed considerably. Extending the oven curing time from 6 to 12 h resulted in higher density and hardness of the specimens, driven by rapid dissolution and condensation, which produced a substantial amount of reactive materials. However, the dissolution and condensation of unreacted particles continued over time at a diminishing rate, contributing to the gradual decrease in the rate of compressive strength improvement. This decline can be attributed to the reduced availability of aluminosilicate particles and decreased solvent accessibility to their inner layers 62.

Curing beyond 12 h led to further moisture loss through the formation of voids and surface cracks 62,63, which ultimately reduced the compressive strength of the mortars when the heat curing period was extended to 24 h. In line with our studies, the optimal compressive strengths were achieved at 100 °C for 8 h in fly ash-based mortars 64 and 12 h in metakaolin paste 65.

Figure 14 illustrates the variations in flexural strength and UPV results concerning oven curing time. The flexural strength of all specimens declined as the curing duration increased from 12 to 24 h. Comparing the differences in flexural strengths between the 3-day and 28-day aged mortars, C80N1S0.7 generally exhibited more significant disparities than C80N0.5S0.6, aligning with the compressive strength trends presented in Table 5.

According to the concrete quality classification 66, most assessed specimens exhibited an “excellent” structural quality, with UPV values ranging from 4624 to 5765 m/s. The exception was the 3-day UPV value of C80N1S0.7, which measured 4510 m/s, indicating a “good” structural quality, suggesting that the specimens were essentially free of significant cracks or pores that could compromise structural integrity 67. Although the UPV values increased with age, they were adversely affected when the oven curing duration was extended to 24 h.

Characterisation of microstructure

SEM and EDS

Figure 15 presents SEM micrographs illustrating the impact of CWP percentage, S: B, NH: NS, and oven curing duration on the microstructure of various geopolymer mortars at 28 days. Among the specimens analyzed, C80N0.5S0.6O12 and C80N1S0.7O12 demonstrated the highest density, characterized by compact and homogeneous structures indicating a substantial presence of reacted products68. The more compact the structure, the fewer voids and defects are observed in the well-distributed mortar matrix. Fewer weak points or voids reduce the likelihood of failure under load, leading to superior compressive strength (see Table 5). Conversely, the low compressive strength of C90N2S0.5O24 is linked to a fragile matrix caused by incomplete geopolymerization and the formation of large voids and cracks. The microstructure of C90N2S0.5O24 confirms that at the lowest S: B, the liquid phase was inadequate to fully react with the binding constituents. When the S: B ratio was increased to 0.7 in C90N2S0.7O24, large voids were replaced by micropores, resulting in a denser structure compared to C90N2S0.5O24 and thereby enhancing the compressive strength23. The NaOH solution detaches Si and Al from the mixture, which acts as binding agents, improving the geopolymerization process 69. The Na₂SiO₃ solution, serving as an alkaline medium, promotes the formation of more silica gel from the mixture, fostering the development of denser Si–O–Si bonds 68. As discussed by Shilar et al.70, the ideal NH: NS ratio should be assessed for each unique geopolymer formulation due to this ratio’s significant role in forming hydroxyaluminosilicate complexes and, consequently, in the development of compressive strength.

The impact of the NH: NS ratio on the geopolymer microstructure is effectively demonstrated by comparing micrographs of C80N0.5S0.6O12 and C80N2S0.6O12. A higher NS content results in a denser structure with increased compressive strength. This outcome can be attributed to two factors: first, NS has a higher viscosity than NH; second, incorporating NS introduces additional Si, accelerating the geopolymerization process and enhancing compressive strength 42. More detailed information on the C80N1S0.7O12 specimen is provided in Fig. 16 at increased magnification, highlighting non-reacted and partially reacted particles and the dense surfaces characteristic of geopolymer matrix formation.

The effect of curing duration in the oven is demonstrated by comparing the microstructures of C80N0.5S0.6O12 and C80N0.5S0.6O24. The coarser microstructure observed in C80N0.5S0.6O24, which exhibits higher porosity and more pronounced cracks, indicates that prolonged oven curing (24 h) leads to excessive moisture escape, resulting in a simultaneous deterioration of the physical and mechanical properties of the specimens 62. Generally, the optimal curing duration depends on the morphology and chemical composition of the mortars, leading to varying findings across studies 61,63,64,71. Micrographs of C100N0.5S0.6O12 and C80N0.5S0.6O12 show that replacing CWP with RGP up to 20 wt% significantly reduces the porosity of the mortar surface. As a rich source of amorphous Si, RGP can actively participate in the geopolymerization process, enhancing the formation of aluminosilicate gels. It is important to note that a suitable alkaline environment and adequate amounts of Al and Si are essential for favourable geopolymerization conditions 9,37.

The SEM images and EDS spectra of selected areas for C80N0.5S0.6O12, C100N0.5S0.6O12, and C80N2S0.6O12 are presented in Fig. 17. All three mortars contain Si, Al, sodium, calcium, and trace amounts of potassium and magnesium. Calcium content (8–12% from CWP and RGP) enhances the likelihood of forming C–S–H hydrates, which coexist with N–A–S–H, contributing to improved density and homogeneity of the microstructure 72. The Ca/Si ratio ranges from 0.25–0.37, which is higher than that in glass cullet geopolymer mortar (Ca/Si = 0.07–0.21)73, but significantly lower than in various GBFS mortars (Ca/Si > 1.06) 42,68. The Si/Al ratio is maximized in C80N0.5S0.6O12, correlating with its highest compressive strength and dense microstructure. A higher Si/Al ratio enhances the densification of the geopolymer gel, leading to more effective aggregate binding by a dense matrix. Furthermore, higher Si/Al ratios favor the formation of Si–O–Si bonds, stronger than Si–O–Al and Al–O–Al bonds 73.

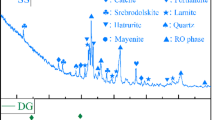

FTIR spectra

The geopolymer formation process starts with the dissolution of Si and Al species by alkaline solutions. The dissolved species then undergo geopolymerization, resulting in the formation of aluminosilicate geopolymers. FTIR spectroscopy is a valuable technique for examining the atomic structure of these reactive species. Figure 18 presents the FTIR spectra of C80N1S0.7O12 and C80N0.5S0.6O12 mortars and the raw waste materials over the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm⁻1 with marked peaks. The absorption peak at 463 cm⁻1 corresponds to Si–O–Si and O–Si bonds’ bending vibrations. The intensity of this band decreases in the geopolymer samples compared to the raw wastes, indicating the progression of geopolymerization among the species.

The CWP displays a broad absorption band at 1080 cm⁻1, corresponding to Si–O and Al–O bonds. In the mortars, this band shifts towards lower frequencies due to the incorporation of Al4⁺ into the Si–O–Si skeletal structure during the polycondensation process 74. This shift occurs because the Si–O–(Al) bond vibrates at a lower frequency than the Si–O–Si bond due to bond strength and atomic mass differences. The Si–O-Al bond exhibits significantly greater resilience than the Si–O-Si and Al bonds 74,75. Integrating Al+4 ions enhances the connectivity of the geopolymer network, leading to a more robust 3D structure, which allows better load distribution when the mortar is subjected to compressive forces 76. A well-connected network minimizes the crack initiation and propagation probability, critical factors in determining the product’s compressive strength.

Similarly, the O–H stretching vibration at 3450 cm⁻1 shifts to lower frequencies in the presence of Al4⁺ within the reacting binders 77. This O–H stretching is associated with the presence of structural water. Two additional peaks are identified in the geopolymer mortar at approximately 876 cm⁻1 and 1450 cm⁻1. The peak at 876 cm⁻1 confirms the formation of an Al-rich gel, suggesting the presence of Si–O–Al bonds 12. The peak at 1450 cm⁻1 is attributed to O–C–O stretching in carbonate groups, which form due to the reaction between alkali metal hydroxides and atmospheric CO₂ 12,78.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing industrial wastes, specifically ceramic waste powder (CWP) and recycled glass powder (RGP), in producing geopolymer mortars, marking a significant advancement toward eco-friendly concrete that meets sustainability standards in the construction industry. By employing response surface methodology (RSM) and conducting 30 mixing designs, we evaluated the effects of CWP blend percentage, NH: NS ratio, S: B ratio, and oven curing duration on the 3-day and 28-day compressive strengths. The optimization results indicated that the optimal mortar mix consists of 85.8% CWP, an NH: NS of 1.02, an S: B ratio of 0.647, and an oven curing temperature of 100 °C for 12 h, achieving compressive strengths of 22.79 MPa at 3 days and 25 MPa at 28 days. The experimental findings closely matched these predicted optimization results, validating the effectiveness of the RSM models developed. The strong correlation between the predicted and actual compressive strengths confirms the reliability of the optimization process.

Furthermore, the models developed and validated through RSM and ANOVA effectively predicted the compressive strengths and revealed strong relationships between the influencing factors and the responses. Correlation analyses showed significant linear relationships between compressive strength, flexural strength, and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), with flexural strength measurements closely matching the predicted values.

The microstructural analysis confirmed that appropriate alkaline solution levels, incorporation of RGP into the CWP mortar, and an optimal NH: NS contributed to a denser geopolymer structure, aligning with the optimization results that indicated the ideal mix proportions. However, prolonged heat curing beyond the optimal duration resulted in increased porosity and surface cracks due to moisture vaporization, underscoring the importance of adhering to the optimized curing conditions. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) provided evidence of successful geopolymerization, validating the transformation of the raw materials into the geopolymer product as predicted by the optimization models. These findings underscore the potential of using CWP and RGP as sustainable materials in geopolymer mortar production, contributing to waste reduction and environmental sustainability in the construction industry. The close alignment between the experimental results and optimization predictions confirms the effectiveness of the optimization process and provides confidence in the practical application of these optimized mix designs.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to proprietary information and intellectual property restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hassan, A., Arif, M. & Shariq, M. A review of properties and behaviour of reinforced geopolymer concrete structural elements: A clean technology option for sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 245, 118762 (2020).

Rajaee, K., Pourabbas Bilondi, M., Barimani, M. H., Amiri Daluee, M. & Zaresefat, M. Effect of gradations of glass powder on engineering properties of clay soil geopolymer. Case Stud. Construct. Mater. 21, e03403 (2024).

Verma, M. & Nirendra, D. Geopolymer concrete: A way of sustainable construction. IJRRA 5, 201–205 (2018).

Safarzadeh, Z., Bilondi, M. P. & Zaresefat, M. Investigating the strength and durability of eco-friendly geopolymer cement with glass powder additives. SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4374847 (2023).

Farooq, F. et al. Geopolymer concrete as sustainable material: A state of the art review. Constr. Build Mater. 306, 124762 (2021).

Zangooeinia, P., Moazami, D., Bilondi, M. P. & Zaresefat, M. Improvement of pavement engineering properties with calcium carbide residue (CCR) as filler in Stone Mastic Asphalt. Results Eng. 20, 101501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101501 (2023).

Wong, B. Y. F., Wong, K. S. & Phang, I. R. K. A review on geopolymerisation in soil stabilization. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 495, 012070 (2019).

Elyamany, H. E., Abd Elmoaty, A. E. M. & Elshaboury, A. M. Setting time and 7-day strength of geopolymer mortar with various binders. Constr. Build Mater. 187, 974–983 (2018).

Pourabbas Bilondi, M., Toufigh, M. M. & Toufigh, V. Experimental investigation of using a recycled glass powder-based geopolymer to improve the mechanical behavior of clay soils. Constr. Build Mater. 170, 302–313 (2018).

Jindal, B. B. Investigations on the properties of geopolymer mortar and concrete with mineral admixtures: A review. Constr. Build Mater. 227, 116644 (2019).

Safarzadeh, Z., Pourabbas Bilondi, M. & Zaresefat, M. Laboratory investigation of the effect of using metakaolin and clay on the behaviour of recycled glass powder-based geopolymer mortars. Results Eng. 21, 101974 (2024).

Sarkar, M. & Dana, K. Partial replacement of metakaolin with red ceramic waste in geopolymer. Ceram. Int. 47, 3473–3483 (2021).

Tran, D. T. et al. Precast segmental beams made of fibre-reinforced geopolymer concrete and FRP tendons against impact loads. Eng. Struct. 295, 116862 (2023).

Shilar, F. A. et al. Assessment of destructive and nondestructive analysis for GGBS Based geopolymer concrete and its statistical analysis. Polymers (Basel) 14, (2022).

Azad, N. M. & Samarakoon, S. M. S. M. K. Utilization of industrial by-products/waste to manufacture geopolymer cement/concrete. Sustainability 13, 873 (2021).

Çelik, A. İ et al. Use of waste glass powder toward more sustainable geopolymer concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 8533–8546 (2023).

Wasim, M., Ngo, T. D. & Law, D. A state-of-the-art review on the durability of geopolymer concrete for sustainable structures and infrastructure. Constr. Build. Mater. 291, 123381 (2021).

Verma, M. et al. Geopolymer concrete: A material for sustainable development in indian construction industries. Crystals (Basel) 12, 514 (2022).

Sharmin, S., Sarker, P. K., Biswas, W. K., Abousnina, R. M. & Javed, U. Characterization of waste clay brick powder and its effect on the mechanical properties and microstructure of geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 412, 134848 (2024).

Nazari, A., Bagheri, A. & Riahi, S. Properties of geopolymer with seeded fly ash and rice husk bark ash. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 528(24), 7395–7401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2011.06.027 (2011).

Bhavsar, J. K. & Panchal, V. Ceramic waste powder as a partial substitute of fly ash for geopolymer concrete cured at ambient temperature. Civ. Eng. J. 8, 1369–1387 (2022).

Luhar, I. et al. Assessment of the suitability of ceramic waste in geopolymer composites: An appraisal. Materials 14, 3279 (2021).

Shoaei, P. et al. Waste ceramic powder-based geopolymer mortars: Effect of curing temperature and alkaline solution-to-binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 227, 116686 (2019).

Rashad, A. M., Essa, G. M. F., Mosleh, Y. A. & Morsi, W. M. Valorization of ceramic waste powder for compressive strength and durability of fly ash geopolymer cement. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 49, 5653–5665 (2024).

Huseien, G. F., Ismail, M., Khalid, N. H. A., Hussin, M. W. & Mirza, J. Compressive strength and microstructure of assorted wastes incorporated geopolymer mortars: Effect of solution molarity. Alex. Eng. J. 57, 3375–3386 (2018).

Huseien, G. F. et al. Properties of ceramic tile waste based alkali-activated mortars incorporating GBFS and fly ash. Constr. Build Mater. 214, 355–368 (2019).

Kaya, M. Mechanical properties of ceramic powder based geopolymer mortars. Mag. Civ. Eng. 112 (2022).

Kaya, M. The effect of micro-SiO2 and micro-Al2O3 additive on the strength properties of ceramic powder-based geopolymer pastes. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 24(1), 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-021-01323-3 (2022).

Vafaei, M., Allahverdi, A., Dong, P. & Bassim, N. Acid attack on geopolymer cement mortar based on waste-glass powder and calcium aluminate cement at mild concentration. Constr. Build. Mater. 193, 363–372 (2018).

ASTM C349–18. Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars. Annual Book of ASTM Standards vol. 04.01 (2018).

ASTM C348–21. Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Hydraulic-Cement Mortars. Annual Book of ASTM Standards vol. 04.01 (2021).

ASTM C597–16. Test Method for Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. https://doi.org/10.1520/C0597-16 (2016).

Sun, Q., Zhu, H., Li, H., Zhu, H. & Gao, M. Application of response surface methodology in the optimization of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Rev. Rom. Mater. 48, 45–52 (2018).

Dashti, P., Ranjbar, S., Ghafari, S., Ramezani, A. & Nejad, F. M. RSM-based and environmental assessment of eco-friendly geopolymer mortars containing recycled waste tire constituents. J. Clean. Prod. 428, 139365 (2023).

Aygörmez, Y., Canpolat, O. & Al-mashhadani, M. M. A survey on one year strength performance of reinforced geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 264, 120267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120267 (2020).

Abdellatief, M., Alanazi, H., Radwan, M. K. H. & Tahwia, A. M. Multiscale characterization at early ages of ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete. Polymers 14(24), 5504. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14245504 (2022).

Bilondi, M. P., Toufigh, M. M. & Toufigh, V. Using calcium carbide residue as an alkaline activator for glass powder–clay geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 183, 417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.06.190 (2018).

Mermerdaş, K., Algın, Z. & Ekmen, Ş. Experimental assessment and optimization of mix parameters of fly ash-based lightweight geopolymer mortar with respect to shrinkage and strength. J. Build. Eng. 31, 101351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101351 (2020).

Atabey, İİ, Karahan, O., Bilim, C. & Atiş, C. D. The influence of activator type and quantity on the transport properties of class F fly ash geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 264, 120268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120268 (2020).

Miao, S., Zhong, Q. & Peng, H. Regularized multivariate polynomial regression analysis of the compressive strength of slag-metakaolin geopolymer pastes based on experimental data. Constr. Build. Mater. 303, 124529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124529 (2021).

Srinivasa, A. S., Swaminathan, K. & Yaragal, S. C. Microstructural and optimization studies on novel one-part geopolymer pastes by Box-Behnken response surface design method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 18, e01946 (2023).

Kubba, Z. et al. Impact of curing temperatures and alkaline activators on compressive strength and porosity of ternary blended geopolymer mortars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 9, e00205 (2018).

Ma, Z., Dan, H.-C., Tan, J., Li, M. & Li, S. Optimization design of MK-GGBS based geopolymer repairing mortar based on response surface methodology. Materials 16, 1889 (2023).

Verma, M. & Dev, N. Effect of liquid to binder ratio and curing temperature on the engineering properties of the geopolymer concrete. Silicon (2022).

Ghafoori, N., Najimi, M. & Radke, B. Natural Pozzolan-based geopolymers for sustainable construction. Environ. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5898-5 (2016).

Girish, M. G., Shetty, K. K. & Nayak, G. Effect of slag sand on mechanical strengths and fatigue performance of paving grade geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42947-023-00363-2 (2023).

Hardjasaputra, H. et al. Study of mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 615, 012009 (2019).

Cyr, M., Idir, R. & Poinot, T. Properties of inorganic polymer (geopolymer) mortars made of glass cullet. J. Mater. Sci. 47(6), 2782–2797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-011-6107-2 (2012).

Omer, S. A., Demirboga, R. & Khushefati, W. H. Relationship between compressive strength and UPV of GGBFS based geopolymer mortars exposed to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 94, 189–195 (2015).

Mardani-Aghabaglou, A., Tuyan, M., Cakir, O. A. & Ramyar, K. Effect of recycled aggregates on strength and alkali silica reaction (ASR) potential of mortar mixtures. In Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on Advances in Civil Engineering, Ankara (2012).

Akbar, A. et al. Sugarcane bagasse ash-based engineered geopolymer mortar incorporating propylene fibers. J. Build. Eng. 33, 101492 (2021).

Mo, K. H., Mohd Anor, F. A., Alengaram, U. J., Jumaat, M. Z. & Rao, K. J. Properties of metakaolin-blended oil palm shell lightweight concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 22, 852–868 (2018).

Kabirova, A. et al. Physical and mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer mortars containing various waste powders. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 27, 437–456 (2023).

Sağır, M. A., Karakoç, M. B., Özcan, A., Ekinci, E. & Yolcu, A. Effect of silica fume and waste rubber on the performance of slag-based geopolymer mortars under high temperatures. Struct. Concrete 24, 6690–6708 (2023).

Al-Swaidani, A., Soud, A. & Hammami, A. Improvement of the early-age compressive strength, water permeability, and sulfuric acid resistance of scoria-based mortars/concrete using limestone filler. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 1–17 (2017).

Ipek, S. & Mermerdaş, K. Engineering properties and SEM analysis of eco-friendly geopolymer mortar produced with crumb rubber. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 7, 95–107 (2022).

Verma, M. et al. Experimental analysis of geopolymer concrete: A sustainable and economic concrete using the cost estimation model. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1–16 (2022).

Tanu, H. M. & Unnikrishnan, S. Mechanical strength and microstructure of GGBS-SCBA based geopolymer concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 24, 7816–7831 (2023).

Qin, T. S., Lim, N. H. A. S., Jun, T. Z. & Ariffin, N. F. Effect of low molarity alkaline solution on the compressive strength of fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 13, 155–164 (2022).

Choi, Y., Kang, J.-W., Hwang, T.-Y. & Cho, C.-G. Evaluation of residual strength with ultrasonic pulse velocity relationship for concrete exposed to high temperatures. Adv. Mech. Eng. 13, 168781402110349 (2021).

Adam, A. A. & Horianto, X. X. X. The effect of temperature and duration of curing on the strength of fly ash based geopolymer mortar. Procedia Eng. 95, 410–414 (2014).

Wongpattanawut, W., & Ayudhya, I. N. Effect of Curing Temperature on mechanical properties of sanitary ware porcelain based geopolymer mortar. Civ. Eng. J. 9, 1808–1827 (2023).

Patankar, S. V., Ghugal, Y. M. & Jamkar, S. S. Effect of concentration of sodium hydroxide and degree of heat curing on fly ash-based geopolymer mortar. Indian J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 1–6 (2014).

Bachtiar, E. The connection between oven curing duration and compressive strength on C-type fly ash based geopolymer mortar’.’. ARPN J. Eng. App. Sci. 15, 577–582 (2020).

Yun Ming, L. et al. Effect of curing regimes on metakaolin geopolymer pastes produced from geopolymer powder. Adv. Mat. Res. 626, 931–936 (2012).

Mahir Mahmod, H., Farah Nora Aznieta, A. A. & Gatea, S. J. Evaluation of rubberized fibre mortar exposed to elevated temperature using destructive and non-destructive testing. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 21, 1347–1358 (2017).

Mansourghanaei, M., Biklaryan, M. & Mardookhpour, A. Experimental study of modulus of elasticity, capillary absorption of water and UPV in nature-friendly concrete based on geopolymer materials. Int. J. Adv. Struct. Eng. 12, 607–615 (2022).

Huseien, G. F., Mirza, J., Ismail, M. & Hussin, M. W. Influence of different curing temperatures and alkali activators on properties of GBFS geopolymer mortars containing fly ash and palm-oil fuel ash. Constr. Build Mater. 125, 1229–1240 (2016).

Shilar, F. A., Ganachari, S. V., Patil, V. B. & Nisar, K. S. Evaluation of structural performances of metakaolin based geopolymer concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 20, (2022).

Shilar, F. A., Ganachari, S. V., Patil, V. B., Neelakanta Reddy, I. & Shim, J. Preparation and validation of sustainable metakaolin based geopolymer concrete for structural application. Constr. Build Mater. 371 (2023).

Shukor Lim, N. H. A. et al. Effect of Curing conditions on compressive strength of FA-POFA-based geopolymer mortar. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 431, 092007 (2018).

Nuaklong, P. et al. Properties of high-calcium and low-calcium fly ash combination geopolymer mortar containing recycled aggregate. Heliyon 5, e02513 (2019).

Arellano-Aguilar, R., Burciaga-Díaz, O., Gorokhovsky, A. & Escalante-García, J. I. Geopolymer mortars based on a low grade metakaolin: Effects of the chemical composition, temperature and aggregate:binder ratio. Constr. Build Mater. 50, 642–648 (2014).

Sun, Z. et al. Synthesis and thermal behavior of geopolymer-type material from waste ceramic. Constr. Build Mater. 49, 281–287 (2013).

Shilar, F. A. et al. Optimization of Alkaline activator on the strength properties of geopolymer concrete. Polymers (Basel) 14 (2022).

Huseien, G. F., Kubba, Z., Mhaya, A. M., Malik, N. H. & Mirza, J. Impact resistance enhancement of sustainable geopolymer composites using high volume tile ceramic wastes. J. Compos. Sci. 7, 73 (2023).

Kaya, M. et al. The effect of sodium and magnesium sulfate on physico-mechanical and microstructural properties of Kaolin and ceramic powder-based geopolymer mortar. Sustainability 14, 13496 (2022).

Ng, C. et al. A review on microstructural study and compressive strength of geopolymer mortar, paste and concrete. Constr. Build Mater. 186, 550–576 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and appreciate Parsian Pazh laboratory of soil, concrete, and weld that supported this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meysam Pourabbas Bilondi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Project administration. Vahideh Ghaffarian: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Review and editing, Visualisation, Supervision. Mahdi Amiri Daluee: Conceptualisation, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Reyhaneh Pakizehrooh: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Visualisation. Saeed Hosseini Tazik: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Review and editing, Data curation, Visualisation. Alireza Behzadian: validation, investigation. Mojtaba Zaresefat: writing—original draft, review and editing, data curation, visualisation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pourabbas Bilondi, M., Ghaffarian, V., Amiri Daluee, M. et al. Experimental studies on mix design and properties of ceramic-glass geopolymer mortars using response surface methodology. Sci Rep 15, 282 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82658-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82658-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Experimental and GEP-based evaluation of compressive strength in eco-friendly mortars with waste foundry sand and varying cement grades

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Effect of Inclusion of Recycled Waste Glass Powder in Geopolymer Concrete: A Review on Workability, Mechanical, Durability, and Micro-Structural Performance

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering (2025)