Abstract

Soil salinization is the most prevalent form of land degradation in arid, semi-arid, and coastal regions of China, posing significant challenges to local crop yield, economic development, and environmental sustainability. However, limited research exists on estimating soil salinity at different depths under vegetation cover. This study employed field-controlled soil experiments to collect multi-source remote sensing data on soil salt content (SSC) at varying depths beneath barley growth. Three types of feature variables were derived from the images and filtered using the boosting decision tree (BDT) method. In addition, four machine learning algorithms coupled with seven variable combination groups were applied to establish comprehensively soil salinity estimation models. The performances of estimation model for different crop coverage ratios and soil depth were then evaluated. The results showed that the gaussian process regression (GPR) model, based on the whole variable group for depths of 0 ~ 10 cm and 30 ~ 40 cm, outperformed other models, achieving validation R2 values of 0.774 and 0.705, with RMSE values are 0.185% and 0.31%, respectively. For depths of 10 ~ 20 cm and 20 ~ 30 cm, the random forest (RF) models, incorporating spectral index and texture data, demonstrated superior accuracy with R2 values of 0.666 and 0.714. The study confirms that SSC can be quantitatively estimated at various depths using the machine learning model based on multi-source remote sensing, providing a valuable approach for monitoring soil salinization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, soil salinization area extends 9.21 million hectares, accounting for 6.62% of the total cultivated land. The formation of saline soil is intricate, posing significant challenges for effective detection and dynamic monitoring. Conventionally, soil salinization was assessed through field sampling and chemical analysis, methods that are both time-consuming, and labor-intensive1. In contrast, remote sensing technology offers a rapid and broad-scale approach to gathering data on ground objects across varying temporal and spatial scales, making it an ideal tool for monitoring soil salinity2. The spectral response of soils varies with salt content, with high-salinity soils exhibiting stronger responses in the visible and near-infrared bands compared to lower-salinity soil3. Leveraging remote sensing for the dynamic monitoring of soil salinization is crucial for the efficient management of soil and water resources, providing essential insights into the timing, patterns, and locations of potential changes in soil salinity, thereby facilitating improved resource management and planning4.

In recent years, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) and other aerial remote sensing platforms have advanced rapidly, increasingly finding applications in civilian sectors and gaining prominence in agricultural research. UAVs offer advantages such as portability, high flexibility, and customizable flight durations. Zhao et al.5 used multispectral remote sensing data from three research locations to establish soil salinity inversion models based on support vector machines (SVM), random forest (RF), backpropagation neural network (BPNN), and extreme learning machine (ELM). The results showed that all four spectral index-based models achieved high inversion accuracy. Similarly, Wei et al.6 used a UAV equipped with Micro-MCA (Multiple Camera Array) multispectral sensors to capture images for evaluating soil salinity in a small region of the Hetao Irrigation District. Chen et al.7 developed soil salt content (SSC) estimation models for sunflower fields at different soil depths during the budding and blooming stages using UAV multispectral data. IVUSHKIN et al.8 found that UAVs equipped with multiple sensors of hyperspectral, multispectral, thermal infrared, and LiDAR cameras, hold great potential for monitoring soil salinization. Feature indices, such as the soil salinity index and vegetation index derived from spectral band reflectance transformations, serve as important variables for estimating SSC9. Qi et al.10 collected spectrum reflectance and spectral indices via a UAV-ground cooperative system and applied machine learning (ML) algorithms, such as BPNN, to construct a salinity inversion model. The findings indicated that the developed model effectively captured the salinization level in the study area.

The relationship between soil salinity and remote sensing feature variables was frequently nonlinear due to the interplay of complex factors, including soil, vegetation, and atmospheric signatures11. Commonly, soil salinity was estimated using statistical models, particularly linear regression model such as partial least squares regression (PLSR)12,13. However, the natural relationship between spectral covariates and soil properties was rarely linear14. Machine learning algorithms, known for their capability to handle nonlinear relationships and high dimensional data, often outperform statistical regression models in soil salinity prediction. Algorithms such as RF, SVM and BPNN could capture these intricate nonlinear patterns, making them particularly effective for soil salinity estimation15. For instance, Hu16 compared PLSR and RF methods using hyperspectral first-order differentiation, broadband and narrowband spectral indices as independent variables, finding that the RF model achieved higher predictive accuracy, especially in bare soil area. Utilizing Landsat image data and measured SSC data, Zhang et al17. developed—a SSC inversion model in the Yellow River Delta using three machine learning methods of BPNN, RF, and SVM. Wei et al.6 tested various ML models to identify the most accurate salt estimation model. However, the prediction accuracy of individual ML algorithm could vary under different conditions. Therefore, evaluating the performance of multiple ML regression algorithms is essential for developing reliable soil salinity prediction models adaptable to diverse environmental factors.

There is a strong correlation between vegetation growth and soil salinity, as evidenced spectrally in two primary ways: differences in leaf spectral reflectance and significant variations in the texture features of spectral images influenced by soil salinity or leaf characteristics18,19 Studies have shown that texture features are extensively used to reveal variations in vegetation characteristics, and integrating these with spectral information can effectively improve the accuracy of predictive models20,21,22,23,24. Huang et al.25 used Sentinel-2 imagery combined with texture features to significantly improve the classification accuracy of moderate saline soil in the Yellow River Delta region. Nevertheless, while remote sensing was commonly employed for soil salinity detection, the focus has primarily relied on spectral indices6, with limited studies investigating the role of texture features in soil salinity estimation. For bare soil, the spectrum could directly determine the salt content of the soil surface. Conversely, under vegetation coverage, soil salinity can be indirectly assessed through the spectral signatures of the vegetation canopy26.

In recent years, limited studies have focused on estimating soil salinity under vegetation cover. This study aims to develop models for estimating soil salinity at various depths beneath barley growth. In this study, an experiment was carried out for barley growth under soil salt stress conditions, collecting both remote sensing data and soil salinity data at varying soil depths. Three types of remote sensing feature variables were extracted and filtered. Moreover, different combinations of these optimal feature variables were coupled with four machine learning algorithms to develop the most accurate models for soil salinity estimation. The main objectives of this study were to: (1) optimize the feature variables of spectral band, spectral index and texture data based on the BDT method; (2) evaluate the potential and feasibility of different ML algorithms with seven data groups for SSC estimation; (3) validate the accuracy of the soil salt estimation models for different vegetation coverage conditions. This study presented a novel method for dynamically monitoring of soil salinity in agricultural systems, contributing precise irrigation and fertilization practices.

Materials and methods

Study area and experimental design

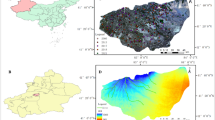

The study area is located at the ecological experimental station of Yangzhou University, situated in the Jianghuai Plain of Jiangsu Province in eastern China (119°24′E, 32°21′N), at an elevation of 5 m (Fig. 1). This region experiences a subtropical monsoon climate, which is marked by a lengthy frost-free averaging 223 days per year. The average annual precipitation, evaporation, and air temperature are recorded at 937 mm, 1063 mm, and 14.8 °C, respectively. Soil samples for the experiment were collected from the Tiaozini reclamation area in Dongtai City, Jiangsu Province. This area has been affected by marine intrusion and groundwater topdressing, resulting in high salinity levels in the soil tillage layer.

The crop studied was barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Four different soil salinity treatments were established: control (no salt), low salinity (3‰), medium salinity (5‰), and high salinity (10‰). The salinity experiment was conducted using a box planting setup with dimensions of 100 cm in length, 40 cm in width, and 40 cm in height, each containing 120 kg of base soil. Each treatment was replicated thrice, resulting in a total of 12 experimental units. Cultivation followed local management practices, encompassing weeding, pest, and disease prevention. Barley was planted in early November, with each box accommodating two rows, and harvested in late May of the following year. To maintain the soil salinity levels of each treatment, the experimental boxes were designed as sealed containers to prevent salt leaching due to precipitation and irrigation.

Data collection and acquisition

Soil salt measurement

During the barley growth stages of reviving-jointing, jointing-filling, and grain-filling maturity, soil apparent electrical conductivity (EC) data were measured every 7 to10 days, in conjunction with the acquisition of multispectral imagery. A total of 84 datasets were collected throughout the barley growth period. Soil electrical conductivity was measured using the EC450 conductivity meter (Spectrum Technologies Co., Ltd., Chicago, IL, USA). The electrode was first calibrated using a calibration solution (conductivity: 1413 μS/cm). Then, the electrode was inserted into the soil profile to measure conductivity at depths of 0 ~ 10 cm, 10 ~ 20 cm, 20 ~ 30 cm, and 30 ~ 40 cm. The soil conductivity values were directly recorded by the handheld reader. During the early, middle, and late stages of crop planting, the soil samples from different soil layers were collected simultaneously with the measurement of apparent soil electrical conductivity values for measuring actual soil water-soluble salts content. The collected soil samples were naturally air-dried and ground. Then the soil sample powder was screened through a 2 mm sieve and mixed evenly. After preparing a 1:5 soil-to-water ratio extraction solution, the mixture was shaken and filtered. Finally, the clear filtrate was taken and placed in a glass evaporation dish into an oven at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved27. Subsequently, the SSC was derived using the empirical relationship between SSC and electrical conductivity established in this study (SSC = 0.0013EC + 0.0008, R2 = 0.92).

Multispectral data acquisition and processing

This study leveraged remote sensing data from multiple UAV-based sensors to enhance soil property monitoring through data fusion. The DJI Inspire 2 UAV platform (DJI Inc., Shenzhen, China) was employed, equipped with an Altum multi-spectral and infrared camera (MicaSense, Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). This camera captured images across six spectral bands (blue, green, red, red edge, near-infrared, and thermal infrared) simultaneously. The UAV flight operations were conducted under optimal conditions of clear skies and calm winds, between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. local time. To ensure high-quality data, the sensor was pre-warmed for 5 min, and a reference plate was used for radiometric calibration before each flight. The flight altitude and cross-track overlap were maintained at 25 m and 75%, respectively, and the camera was oriented vertically downward to achieve a ground resolution of 1.1 cm per pixel. After preprocessing the collected multispectral images by radiation correction, geometric correction, and image mosaicking, reflectance data for each pixel were generated during the crop growth period. A region of interest (ROI) was preset near the center of each plot to extract canopy reflectance.

Vegetation coverage calculation

After collecting multispectral imagery, the canopy light interception of barley was measured using the AccuPAR LP-80 ceptometer (Decagon Devices Inc., Pullman, WA, USA). The LP-80 is equipped with 80 independent sensors, each spaced uniformly at 1 cm intervals and measures solar radiation within the 400–700 nm band in different modes. During the measurement, the sensor was positioned centrally in the plot and aligned with the row direction. Using the photosynthetically active radiation values measured at the top and bottom of the canopy, the instrument automatically calculated the crop’s Leaf Area Index (LAI) using a built-in algorithm that incorporates other variables. Based on previous studies and a classification method considering similar geographical features and vegetation types28, vegetation cover ratios were divided into low (0 ~ 0.45), medium (0.46 ~ 0.75) and high (0.76 ~ 1) coverage, corresponding to LAI values ranging from 0 ~ 1, 1.1 ~ 2.5, and > 2.5 respectively.

Construction of feature variables

Spectral indices are classical variables that integrate the spectral characteristics of each band of ground objects and enhanced specific information through mathematical transformations and combinations of reflectance values from different bands. Salinity indices, commonly used for the rapid assessment of soil salinization, exhibit a strong correlation with bare soil salinity29. Similarly, vegetation indices are frequently used for the quantitative assessment of vegetation growth30. In this study, a selection of widely recognized spectral indicators were employed to monitoring soil salinization, including 15 salinity indices and 15 vegetation indices.

The selected salinity indices include the following: Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI), R-edge Normalized Difference Salinity Index (NDSI-reg), Brightness Index (BI), Salinity Index 1 (SI1), R-edge Salinity Index 1 (SI1-reg), Salinity Index 2 (SI2), R-edge Salinity Index 2 (SI2-reg), Salinity Index 3 (SI3), R-edge Salinity Index 3 (SI3-reg), Salinity Index (SI-T), Salinity Index S1, Salinity Index S2, Salinity Index S3, Salinity Index S5, Salinity Index SI; The selected vegetation indices include: Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), R-edge Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI-reg), Difference Vegetation Index (DVI), R-edge Difference Vegetation Index (DVI-reg), Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), R-edge Difference Vegetation Index (EVI-reg), Triangular Vegetation Index (TVI), Normalized Greenness Index (NDGI), Simple Ratio Index (SR), Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI), Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI), Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI), Visible Light Band Difference Vegetation Index (VDVI), Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index (VARI), Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (GNDVI), and a normalized relative canopy temperature (NRCT). The calculation formulas for these indices were shown in Table 1.

The texture of the image indicated variations in the color and gray levels of the soil surface, closely related to the soil salt and water content. In this study, the statistical Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) method was used to extract the textural features of the images. GLCM is a prevalent method widely used for image feature extraction, texture analysis, and quality evaluation, describing the correlation between pixel gray levels within images46. Eight characteristic variables including mean (MEA), variance (VAR), uniformity (HOM), contrast (CON), difference (DIS), entropy (ENT), second-order moment (SEC) and correlation (COR) were calculated for each band of UAV multispectral images using the second-order statistical filtering tool. In total, this study incorporated 5 band reflectance values, canopy temperature, 31 spectral indices, and 40 texture feature data, amounting to 77 feature variables as independent variables.

Feature variable selection and set construction

Optimization of characteristic variables

To optimize the complexity of the model’s input variables, this study employed the BDT method to refine the selection of 77 characteristic variables. BDT is an embedded method that can predictor importance for the tree by summing the changes in mean squared error (MSE) due to splits on each predictor and dividing the sum by the number of branch nodes47. The steps involved in this optimization process included: (1) dividing the feature variables into twenty groups; (2) calculating the importance scores of feature variables in each dataset based on BDT; (3) normalizing the importance scores across various data categories; and (4) performing statistical analysis and sorting on the normalized data from the 20 groups. Therefore, the obtained datasets were randomly divided, with 70% allocated to the training subset and the remaining 30% reserved for the test subset. This process was repeated 20 times. The results from each iteration were normalized across different groups (spectral band reflectance group, spectral index group, and texture data group). Based on the contribution degree of characteristic variables within each group, a threshold of 0.1 was established to select the pivotal variables for model training and development.

Construction of model training

The construction of a predictive model necessitates the careful extraction of input features and the judicious selection of appropriate ML algorithms. To investigate the impact of various features on model performance, feature combinations were categorized as follows:

Single Variable Groups: (1) Band Reflectance (Plan 1): This group comprise the original reflectance values of each spectral band. These values directly represent the physical and chemical properties of the soil, serving as the primary features for predicting the SSC. (2) Spectral Index (Plan 2): This group includes of various spectral indices, calculated from different spectral bands reflectance. These indices are designed to enhance specific soil or vegetation characteristics. (3) Texture Feature (Plan 3): This group is derived from spectral data, such as the gray level co-occurrence matrix, can capture subtle changes and the spatial structure of the soil surface.

Pairwise Variable Groups: (1) Spectral Band Reflectance and Indices Combination (Plan 4): This combination retains the original spectral information while incorporating enhanced data, potentially providing a more comprehensive understanding of soil salinity changes. (2) Spectral Band Reflectance and Texture Feature Combination (Plan 5): By integrating the complementary advantages of both data types, this combination reveals spectral characteristics and captures the spatial heterogeneity of the soil surface. (3) Spectral Indices and Texture Feature Combination (Plan 6): This combination enriches the enhanced information with spatial structure data, potentially improving the model’s generalization capability.

Full Variable Group (Plan 7): This group contained all types of data related to spectral band reflectance, spectral indices, and texture features. The comprehensive inclusion of all potentially relevant information aimed to enhance the model’s generalization capabilities and predictive performance.

Machine learning models

Based on the measured SSC and the selected feature variables, four machine learning methods of RF, SVM, GPR, and BPNN methods was used to construct soil salinity estimation models.

RF is an ensemble learning method used to develop predictive models for classification and regression tasks by employing a collection of randomly generated decision trees48. In recent years, RF has gained popularity for estimating vegetation growth parameters as well as soil physical and chemical characteristics. For instance, Huang et al.49 established several models for estimating soil salinity based on Landsat-8 OLI images in their study of oasis soil salinity in arid regions, they found that the RF model achieved higher estimation accuracy compared to traditional statistical models. Similarly, Sui et al.50 developed a soil salinity estimation model that integrated original observations and satellite data, incorporated hydrological connectivity measurements along with the RF algorithm.

SVM is a method that implemented structural risk minimization, effectively addressing challenges associated with small sample sizes, nonlinearity, and high-dimensional data. SVM demonstrates strong expressive capability, generalization ability, and learning efficiency. It seamlessly integrates with multi-source information, resulting in enhanced estimation accuracy51. For example, Cai et al. (2010) combined multispectral and texture features, utilizing the SVM classifier to identify saline-affected soil. The study confirmed that the SVM classifier effectively extracted information on soil salinization distribution in the Yinchuan Plain. Similarly, Guan et al.52 introduced SVM theory into the dynamic prediction of soil electrical conductivity values, constructing a dynamic model for soil salinity prediction aimed at optimizing irrigation water in salinized areas.

GPR is a nonparametric Bayesian regression method that predicts outcomes by assuming the data follow a multivariate Gaussian distribution, thereby providing an estimate of prediction uncertainty. It was flexible and efficient for small datasets but can be computationally expensive and challenging to scale for larger datasets. Furthermore, selecting and tuning the appropriate kernel function necessitates substantial expertise and experimentation.

BPNN is a feedforward network composed of multiple neurons that can learn and identify nonlinear relationships in complex systems. It demonstrates a strong self-learning ability, adaptability, and resistance to interference, making it highly promising for estimating of soil physical and chemical parameters. For instance, Wang et al.53 successfully established a prediction model for soil moisture and salinity using BPNN in conjunction with Landsat-8 satellite data.

In the realm of machine learning models, parameter determination is crucial for model performance. For instance, the hyperparameters such as minimum leaf sizes and maximal number of branch nodes in RF model, the kernel parameters of function, scale, epsilon in SVM model, as well as parameters of explicit basis, covariance function in GPR model and activation function, layer sizes, and regularization in BPNN model can significantly influence training outcomes and simulation accuracy. In addition, some less important parameters, such as learning rate and standardization, indirectly affect the model training efficiency. In this study, the Bayesian optimization algorithm, integrated into the machine learning toolkit was used. This algorithm fine-tunes parameters to minimize cross-validation loss and ultimately identify the optimal parameters set, enabling the model to achieve optimal performance.

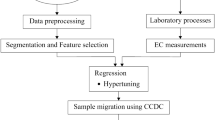

Technical workflow

This study aims to identify the most effective set of variables for accurately predicting SSC, thereby enhancing the overall performance and applicability of the model across various soil depths. SSC was designated as the dependent variable, while different groups of variables served as the independent variables. The sample data were randomly divided into two groups, with 70% allocated for model training and 30% for validation. Four distinct machine learning methods (RF, SVM, GPR, and BPNN) were employed to estimate SSC, with each method constructing corresponding prediction models and optimizing performance through model hyperparameters tuning. To further improve model accuracy, tenfold cross-validation was used to construct and train the SSC estimation models (Fig. 2).

Results

Statistical of soil salinity distribution

The salt content at various sampling points and soil depths was categorized as follows: non-saline soil (< 0.2% salt content), mild salinization (0.2 ~ 0.5%), severe salinization (0.5 ~ 1.0%), and saline soil (> 1.0%). The non-saline treatment exhibited an average salt content of 0.214%, while the low-salt treatment averaged 0.257%. The medium-salt treatment recorded an average salt content of 0.418%, and the high-salt treatment had an average value of 1.353%. Statistical analysis of the obtained salt content data revealed that at a soil depth of 0 to 10 cm, the measured SSC were generally lower than at deeper depths, varying from 0.031% to 1.04%, with an average of 0.428%. At a depth of 10 to 20 cm, the SSC ranged from 0.087% to 1.406%, with an average of 0.561%. The highest SSC was observed at the depth of 20 to 30 cm, with an average SSC of 0.633%, varying between 0.055 to 1.806%. The SSC distribution at 30 to 40 cm was similar to that in the 10 to 20 cm layer, with an average of 0.619%. Based on these criteria, the measured salt grade distribution in the study area was shown in Fig. 3.

Contribution and selection of feature variables

Feature selection is a fundamental component of machine learning and data analysis, aimed at identifying the most relevant and representative features from the original dataset to enhances both model performance and computational efficiency. In this study, the importance of 77 feature variables from three types of data for different soil depths was calculated (Fig. 4). After normalizing the feature variables and setting a threshold of 0.1, the relevant features were screened. Common variables across different depths were then selected for training the ML model, Finally, the selected variables for the different groups were as follows: Band reflectance: B, R-edge, and NIR; Spectral Index: SI2, SI2-reg, BI, SI-T, DVI, EVI, SAVI, OSAVI, DVI-reg, EVI-reg, and MSAVI; Texture feature: B-MEA, B-VAR, B-CON, B-ENT, B-SEC, G-VAR, RE-MEA, NIR-MEA, NIR-HOM, NIR-ENT, and NIR-SEC. In total, 25 feature variables were filtered for modeling.

Comparison of model performance for various ML methods and data groups

The optimal variables from the three data types of band reflectance, spectral index, and texture data along with their combinations, were used as independent variables, with SSC served as the target variable in the machine learning (RF, SVM, GPR, and BPNN) model to develop a soil salinity prediction model. The prediction accuracies of these models, based on various combinations of variables, were shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

Figures 5 and 6 demonstrate that, for each algorithm, the band reflectance and spectral index variables performed effectively in estimating SSC at a depth of 0 to 10 cm within the single-variable groups. Among these, the BPNN model, based on the spectral index, demonstrated the best performance, achieving an R2 of 0.74 and RMSE of 0.26%. In the multivariate combination group, the GPR model, utilizing the entire variable set, proved most effective, exhibiting a stable R2 of approximately 0.77 and an RMSE of 0.24%, along with excellent overall stability. The RF model identified band reflectance as the most significant single variable for SSC at a depth of 10 to 20 cm, whereas the SVM model produced the worst estimation. Across the four approaches tested, texture feature alone yielded suboptimal results, with an average RMSE exceeding 0.34%. However, the RF model that incorporated both texture and spectral index data, outperformed the others in the multivariate combination, achieving a mean RMSE of 0.31% and an R2 of approximately 0.61, making it as the most effective model overall. Additionally, the GPR model consistently outperformed other approaches, while the SVM and BPNN models delivered less accurate predictions across all groups.

At a depth of 20 to 30 cm, the RF model constructed using band reflectance and spectral index, demonstrated superior performance, achieving average R2 values of 0.62 and 0.67, along with mean RMSE of 0.31% and 0.29%, respectively. This model outperformed those developed with the other three algorithms. Among the multivariate combinations, the integration of spectral index and texture feature yielded the best results within the RF model, with an R2 of 0.67 and an RMSE of 0.29%. Similarly, the GPR algorithm, when applied specifically to texture feature, exhibited higher accuracy than the other three algorithms. The SVM model achieved its highest accuracy when all variables were combined. In contrast, the models based on band reflectance and spectral index data in the GPR and BPNN algorithms showed slightly higher accuracy than other combinations, with R2 values of 0.64 and 0.58, and RMSE values of 0.30% and 0.35%, respectively.

The RF model using textural feature as a single variable exhibited the lowest accuracy at a depth of 30 to 40 cm, with an average RMSE of 0.39% and R2 of 0.37. In contrast, the RF model constructed using the spectral index demonstrated higher accuracy than the other three models. Within the multi-variable combination group, the SVM model maintained consistent accuracy, with an R2 of approximately 0.55. The GPR model, when applied to the complete variable set, showed superior accuracy compared to other combinations. Notably, the BPNN model exhibited better accuracy when based on band reflectance and spectral index data than the other models.

In conclusion, soil salinity estimation at various depths was enhanced through the application of diverse machine learning techniques, with the effectiveness of these methods differing across different modeling groups. The most effective approach for estimating soil salinity was the GPR model using the entire variable group, particularly for surface (0 ~ 10 cm) and deep (30 ~ 40 cm) measurements. However, for middle-depth soils (10 ~ 20 cm and 20 ~ 30 cm), the RF model using spectral index and texture feature, yielded the best results. The RF model effectively reduced the variance of individual trees by integrating multiple decision trees, thereby enhancing the model’s stability and estimation accuracy. Although the SVM and BPNN models performed slightly worse overall than GPR and RF models, they still demonstrated reasonable predictive capabilities within specific categories.

Outer-sample validation and analysis

The performance of optimal estimation models has been evaluated 20 times using outer-samples (non-training) data (Fig. 7). At a soil depth of 0 to10 cm, the R2 values of the validation set fluctuated between 0.6 and 0.9, with an average R2 of 0.77 and the RMSE values typically ranged from 0.1% to 0.3%, with an average RMSE of 0.185%. These results indicated that the GPR model demonstrated high prediction accuracy and stability for predicting shallow soil salinity. For the 10 to 20 cm depth, the RF model showed favorable performance, with an average R2 and RMSE of 0.67 and 0.325%, respectively. At the 20 to 30 cm depth, the RF model achieved a maximum R2 of 0.87 and a minimum RMSE of 0.212%. In the deepest soil layer, the model’s R2 ranged from a minimum of 0.52 to a maximum of 0.92, indicating high overall accuracy and stability, with RMSE values fluctuated between 0.169% and 0.485%.

The modeling and validation accuracies of four soil salinity estimation models at various depths were compared, with specific models were selected for each depth to optimize estimation results in both modeling and validation sets. The average R2 values across depth in the modeling set exceeded 0.6, while the average RMSE values were below 0.4%, indicating that the models achieved high accuracy and good stability. Finally, based on the optimal SSC estimation model of each soil layer, the salinity profiles of different soil layers in the coastal sliver mud reclamation area were inversion (Fig. 8). This farm has experienced prolonged lateral ocean infiltration, leading to consistently high salinity levels in the cultivated soil layer. Except for the lower terrain in the central region, the soil salinity in other surrounding areas remained below 0.5%. While, as the of soil depth increases, the salinity levels rise, reaching up to 1.5 ~ 2.0%.

Performance of salinity estimations under different vegetation coverage

In this study, the LAI was used as a proxy for vegetation cover, categorized into three distinct levels: low, medium and high. Soil salinity data were stratified based on these vegetation cover classes. The results of SSC estimation under various vegetation covers were presented in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9, all models achieved R2 values greater than 0.4, with the highest value reaching 0.83, indicating that the model accuracy was greatest for soil surface with intermediate vegetation coverage. The models demonstrated good accuracy for soil depths of 0 to 10 cm across all vegetation coverage level, with R2 values exceeding 0.7 and low RMSE values. At a depth of 10 to 20 cm, model accuracy was highest under low vegetation coverage, while it was lowest under medium vegetation coverage. However, at a depth of 20 to 30 cm, maximum validation accuracy was achieved with medium coverage, with R2 values exceeding 0.7 across all three coverage levels. With substantial vegetation coverage, the highest accuracy at 30 to 40 cm was attained, with an RMSE of 0.241% and an R2 of 0.78. Overall, when using the data selected under each vegetation coverage level as the validation set, the preferred models at different depths exhibited robust estimation performance.

Discussion

Soil salinity estimation using UAV remote sensing data plays a positive role in salinity monitoring and management. In this study, we employed spectral data and salinity measurements collected during the vegetation cover period to develop and validate a soil salinity estimation model across various depths. Furthermore, we assessed the model’s performance under different vegetation cover ratios and investigated the impact of vegetation cover on salt estimation in different soil layers.

Feature selection is a crucial step in developing an accurate soil salinity estimation model. Using the BDT method, 25 key features were identified, including band reflectance (e.g., blue, red-edge, and near-infrared), spectral indices (e.g., SI2-reg, EVI, and DVI), and texture data (e.g., mean, variance, and second-order moments of GLCM features). These features effectively captured the spectral properties and the spatial structural information, providing the model with adequate input variables. Studies have shown that the red-edge band was particularly sensitive to soil salinity, with strong correlations to the spectral properties of the vegetation canopy, thereby enhancing the accuracy of soil salinity estimation32,54. Sidike et al.55 employed the PLSR approach to identify soil salinity sensitive bands, highlighting the significant role of near-infrared band in soil salinity assessment. Besides, Fan et al.56 demonstrated that soil salinity correlates with NIR and SWIR bands, which exhibited larger negative correlation coefficients. In this study, the red-edge and near-infrared proved highly significant with SSC at various depths, as they sensitively indicated changes in soil moisture and salt content. This finding aligned with the results reported by Taghadosi et al.57.

Spectral indices such as EVI, EVI-reg, and BI indirectly indicated the salinity status of the soil by enhancing vegetation characteristics. Lobell et al.58 found that EVI outperformed NDVI in salinity monitoring. Spectral index groups, including SI2-reg, EVI-reg, and DVI-reg, which involved calculations with the red-edge band, further emphasizing its importance in soil salinity monitoring, consistent with the findings of Ma et al.59. Additionally, textural features, such as mean, variance, and contrast in the GLCM, were instrumental for capturing subtle changes in soil surface and spatial structure information. Tai60 showed that incorporating texture features could significantly enhance the accuracy of soil salinity estimation models, especially under vegetative cover conditions.

Different modeling data groups also influenced the performance of estimation models. In the single-variable data group, spectral indices significantly contributed to soil salinity estimation, with the RF model demonstrating high accuracy across all four depths (Figs. 5 and 6). Bian et al.61 reported a notable correlation between spectral indices and soil salinity, supporting the effectiveness of these indices in estimation models. Although the model accuracy based on band reflectance was slightly lower than that of the spectral indices, the overall difference was not statistically significant. This finding was consistent with Wang et al.62, who evaluated the prediction accuracy of various variable groups for soil salinity in oasis environments.

In contrast, texture feature alone performed poorly as the single-variables. However, when combined with other variables, the texture information derived from multispectral images could improve the accuracy of soil salinity estimation at different depths beneath vegetation cover. Zheng et al.19 demonstrated that the integrating texture data with spectral information significantly enhanced the accuracy of rice biomass estimation. The texture features from UAV multispectral images provided rich information63, making them applicable for estimating soil salinity at different depths. This study also demonstrated that using sensitive bands and spectral indices as input variables lead to better modeling and validation outcomes in soil salinity estimation. Nevertheless, in multi-variate groups, variables may interact and constrain one another, and combining highly important variables does not always achieve optimal results. For instance, the accuracy of all data groups in the BPNN model was suboptimal compared to other models. Introducing excessive number of independent variables could lead to information redundancy, overfitting, and a decrease in model accuracy64.

Previous studies have highlighted the superiority of machine learning methods for estimating SSC due to the complexity and indirect relationships among variables65. In this study, RF, SVM, GPR and BPNN were employed to model soil salinity at various depths and to identify the most effective model. The evaluation criteria revealed that RF and GPR offered distinct advantages in estimating soil salinity. Although SVM has strong generalization capabilities for addressing nonlinear problems, it remains sensitive to noisy data66. The models exhibited different levels of accuracy in estimating soil salinity across depths. The GPR model showed superior prediction accuracy compared to other methods for both surface and deep soils, while the RF model performed well in intermediate soil layers.

Given the complexity of the soil salinization mechanism and the intricate nonlinear relationships between soil spectral characteristics and soil salinity, machine learning methods are particularly well-suited for elucidating these connections. Their robust nonlinear fitting and generalization capabilities make them ideal for simulating the complex interactions among variables. Ma et al.59 found that the RF model produced better estimation results when predicting the soil salinity in the Ebinur Lake wetland using multispectral and Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data. Wei et al.6 developed SSC estimation models using RF, SVM, and BPNN algorithms, with the RF model achieving the highest prediction accuracy (R2 = 0.84). Additionally, Zhu et al.67 and Yu et al.68 concluded that the RF-based SSC estimation model achieves high accuracy.

Estimating soil salinity during the vegetation cover period primarily involves indirectly obtaining information on soil salinity through the spectral response of crops to it. The vegetation cover ratio of a given crop during this period can correlate with soil salinity levels. The optimal estimation model for various soil depths varies with vegetation cover conditions. Specifically, for soil depths of 0 to 10 cm, the optimal model applied under low and medium vegetation cover conditions, while for high vegetation cover, the model was best suited for depths of 20 to 30 cm. During the vegetation cover period, crops primarily absorb soil water through their lateral roots, making the salinity of the soil layer where these lateral roots are located critical for crop water uptake leading to growth stress69. Higher soil salinity levels in this layer increase stress on crop growth, leading to diminished growth, which is indirectly expressed in the vegetation canopy.

Although current studies on soil salinity monitoring have evolved from relying on single data source to the fusion of multi-source data, and from soil surface salt identification to depth layer salt content estimation, soil salinity distribution exhibits complex variability due to multiple factors such as soil salinization types, soil water content, vegetation cover, and climatic conditions. Consequently, the estimation models often lack robustness when applied across temporal and spatial scales. Future studies may not only focus on multi-scale coordinated monitoring of soil salinization and harness the potential of satellite, aerial, and ground-based sensing data but expand interdisciplinary approaches, such as assimilating remote sensing data with soil water and salt transport models to enable dynamic simulation of soil profile water-salt processes.

Conclusion

This study estimated and analyzed soil salinity content at various depths using UAV multi-spectral data. The analysis involved seven features variable groups derived from band reflectance, spectral indices, and texture features. Additionally, feature variable selection based on the BDT method and four machine learning algorithms (RF, SVM, GPR and BPNN) were incorporated into the estimation model establishment. Key findings are as follows: (1) The estimation accuracy of the RF and GPR models surpassed that of the SVM and BPNN models across all four soil depths. (2) The GPR model, using the full variable set, provided the highest accuracy for estimating SSC at 0 to 10 cm and 30 to 40 cm depths, achieving R2 values of 0.77 and 0.62, with RMSE values of 0.185% and 0.31%, respectively. The RF model, based on the spectral index and texture dataset, was the most accurate for depths of 10 to 20 cm and 20 to 30 cm. (3) Validation using soil salt data under varying vegetation covers showed that the highest accuracy was achieved with medium vegetation coverage at 0 to 10 cm and 20 to 30 cm depths, as well as high vegetation coverage at 10 to 20 cm and 30 to 40 cm depths.

Nonetheless, several limitations still existed in this study. The experiment was conducted under controlled box planting conditions, which may not fully represent the soil salinity in actual field conditions. Additionally, the study did not account for crop type and soil water content, which could influence model accuracy in practical applications. Future study should consider a broader range of influencing factors to further refine the model and enhance the accuracy and stability of soil salinity predictions.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Seifi, M., Ahmadi, A., Neyshabouri, M. R., Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R. & Bahrami, H. A. Remote and Vis-NIR spectra sensing potential for soil salinization estimation in the eastern coast of Urmia hyper saline lake Iran. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 20, 100398 (2020).

Wang, L. W. & Wei, Y. X. Estimating the total nitrogen and total phosphorus content of wetland soils using hyperspectral models. Acta Ecol. Sin 36(16), 5116–5125 (2016).

Rao, B. R. M. et al. Spectral behaviour of salt-affected soils. Int. J. Remote Sensing 16(12), 2125–2136 (1995).

Singh, A. Soil salinization management for sustainable development: A review. J. Environ. Manage. 277(111), 383 (2021).

Zhao, W., Zhou, C., Zhou, C., Ma, H. & Wang, Z. Soil salinity inversion model of oasis in arid area based on UAV multispectral remote sensing. Remote Sensing 14(8), 1804 (2022).

Wei, G. et al. Estimation of soil salt content by combining UAV-borne multispectral sensor and machine learning algorithms. PeerJ 8, 9087 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. UAV remote sensing inversion of soil salinity in field of sunflower. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 51(7), 178–191 (2020).

Ivushkin, K. et al. UAV based soil salinity assessment of cropland. Geoderma 338, 502–512 (2019).

Nicolas, H. & Walter, C. Detecting salinity hazards within a semiarid context by means of combining soil and remote-sensing data. Geoderma 134(1–2), 217–230 (2006).

Qi, G., Zhao, G. & Xi, X. Soil salinity inversion of winter wheat areas based on satellite-unmanned aerial vehicle-ground collaborative system in coastal of the Yellow River Delta. Sensors 20(22), 6521 (2020).

Wang, N. et al. Integrating remote sensing and landscape characteristics to estimate soil salinity using machine learning methods: A case study from Southern Xinjiang China. Remote Sensing 12(24), 4118 (2020).

Zhang, X. & Huang, B. Prediction of soil salinity with soil-reflected spectra: A comparison of two regression methods. Sci. Reports 9(1), 1–8 (2019).

Ghada, S. A PLSR model to predict soil salinity using Sentinel-2 MSI data. Open Geosci. 13(1), 977–987 (2021).

Ge, X. et al. Combining UAV-based hyperspectral imagery and machine learning algorithms for soil moisture content monitoring. PeerJ 7, e6926 (2019).

Poblete, T., Ortega-Farías, S., Moreno, M. A. & Bardeen, M. Artificial neural network to predict vine water status spatial variability using multispectral information obtained from an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Sensors 17(11), 2488 (2017).

Hu, J. (2019). Estimation of Soil Salinity in Arid Area Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing (Doctoral dissertation, Zhejiang University).

Zhang H. Fu X, Zhang Y, et al. (2023). Mapping Multi-Depth Soil Salinity Using Remote Sensing-Enabled Machine Learning in the Yellow River Delta, China. Remote Sensing, 15(24).

Zhang, Z. et al. Inversion of soil salt content by UAV remote sensing under different vegetation coverage. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach 53, 220–230 (2022).

Zheng, H. et al. Enhancing the nitrogen signals of rice canopies across critical growth stages through the integration of textural and spectral information from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) multispectral imagery. Remote Sensing 12(6), 957 (2020).

Yang, H., Wang, Z., Cao, J., Wu, Q. & Zhang, B. Estimating soil salinity using Gaofen-2 imagery: A novel application of combined spectral and textural features. Environ. Res. 217, 114870 (2023).

Ren, J., Li, X., Zhao, K., Fu, B. & Jiang, T. Study of an on-line measurement method for the salt parameters of soda-saline soils based on the texture features of cracks. Geoderma 263, 60–69 (2016).

Andrade, R. et al. Proximal sensor data fusion and auxiliary information for tropical soil property prediction: Soil texture. Geoderma 422, 115936 (2022).

Drielsma, M. J., Love, J., Taylor, S., Thapa, R. & Williams, K. J. General Landscape Connectivity Model (GLCM): A new way to map whole of landscape biodiversity functional connectivity for operational planning and reporting. Ecol. Model. 465, 109858 (2022).

Cai, S., Zhang, R., Liu, L. & Zhou, D. A method of salt-affected soil information extraction based on a support vector machine with texture features. Math. Comput. Model. 51(11–12), 1319–1325 (2010).

Huang, C. et al. Land cover mapping in cloud-prone tropical areas using Sentinel-2 data: Integrating spectral features with Ndvi temporal dynamics. Remote Sensing 12(7), 1163 (2020).

Jia, K. L. & Zhang, J. H. Impacts of different alkaline soil on canopy spectral characteristics of overlying vegetation. Spectrosc. Spect. Anal. 34(3), 782–786 (2014).

Yang, N. et al. Soil salinity inversion at different depths using improved spectral index with UAV multispectral remote sensing. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36(22), 13–21 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Estimating soil salinity with different fractional vegetation cover using remote sensing. Land Degradat. Dev. 32(2), 597–612 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Sensitivity analysis of soil salinity and vegetation indices to detect soil salinity variation by using Landsat series images: Applications in different oases in Xinjiang, China. Acta Ecologica Sinica 37(15), 5007–5022 (2017).

Chi, Y., Sun, J., Liu, W., Wang, J. & Zhao, M. Mapping coastal wetland soil salinity in different seasons using an improved comprehensive land surface factor system. Ecol. Indicat. 107, 105517 (2019).

Khan, N. M., Rastoskuev, V. V., Shalina, E. V., & Sato, Y. (2001, November). Mapping salt-affected soils using remote sensing indicators-a simple approach with the use of GIS IDRISI. In 22nd Asian conference on remote sensing (Vol. 5, No. 9).

Zhang, S. et al. Integrated satellite, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and ground inversion of the SPAD of winter wheat in the reviving stage. Sensors 19(7), 1485 (2019).

Song, C. Y., Ren, H. X. & Huang, C. Estimating soil salinity in the Yellow River Delta, Eastern China—an integrated approach using spectral and terrain indices with the generalized additive model. Pedosphere 26(5), 626–635 (2016).

Abbas, A., Khan, S., Hussain, N., Hanjra, M. A. & Akbar, S. Characterizing soil salinity in irrigated agriculture using a remote sensing approach. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 55, 43–52 (2013).

Tripathi, N. K., Rai, B. K., & Dwivedi, P. (1997, October). Spatial modeling of soil alkalinity in GIS environment using IRS data. In Proceedings of the 18th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Vol. 20, No. 25, pp. 81–86).

Allbed, A., Kumar, L. & Aldakheel, Y. Y. Assessing soil salinity using soil salinity and vegetation indices derived from IKONOS high-spatial resolution imageries: Applications in a date palm dominated region. Geoderma 230, 1–8 (2014).

Zhou, L. et al. Research on quick dynamic monitoring of soil salinization in Qaidam Basin. Sci. Surv. Mapp. 46(7), 99–106 (2021).

Khan, N. M., Rastoskuev, V. V., Sato, Y. & Shiozawa, S. Assessment of hydrosaline land degradation by using a simple approach of remote sensing indicators. Agric. Water Manage. 77(1–3), 96–109 (2005).

Liu, H. Q. & Huete, A. A feedback based modification of the NDVI to minimize canopy background and atmospheric noise. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 33(2), 457–465 (1995).

Lyon, J. G., Yuan, D., Lunetta, R. S. & Elvidge, C. D. A change detection experiment using vegetation indices. Photogram. Eng. Remote Sensing 64(2), 143–150 (1998).

Birth, G. S. & McVey, G. R. Measuring the color of growing turf with a reflectance spectrophotometer 1. Agron. J. 60(6), 640–643 (1968).

Arachchi, M. H., Field, D. J. & McBratney, A. B. Quantification of soil carbon from bulk soil samples to predict the aggregate-carbon fractions within using near-and mid-infrared spectroscopic techniques. Geoderma 267, 207–214 (2016).

Ma, S., He, B., Ge, X. & Luo, X. Spatial prediction of soil salinity based on the Google Earth Engine platform with multitemporal synthetic remote sensing images. Ecol. Inform. 75, 102111 (2023).

Gitelson, A. A., Kaufman, Y. J., Stark, R. & Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sensing Environ. 80(1), 76–87 (2002).

Elsherbiny, O., Zhou, L., Feng, L. & Qiu, Z. Integration of visible and thermal imagery with an artificial neural network approach for robust forecasting of canopy water content in rice. Remote Sensing 13(9), 1785 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Dong, Y., Huang, W., Liu, L. & Ma, H. Wheat fusarium head blight detection using UAV-based spectral and texture features in optimal window size. Remote Sensing 13(13), 2437 (2021).

Drucker, H., Cortes, C. (1995). Boosting decision trees. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 8.

Mutanga, O., Adam, E. & Cho, M. A. High density biomass estimation for wetland vegetation using WorldView-2 imagery and random forest regression algorithm. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinform. 18, 399–406 (2012).

Huang, X.Y., Wang, X.M., & Kawuqiati, B. (2023). Inversion of soil salinity of an oasis in an arid area based on Landsat8 OLI images. Remote Sensing Nat. Resources 35(1).

Sui, H. et al. Soil salinity estimation over coastal wetlands based on random Forest algorithm and hydrological connectivity metric. Front. Marine Sci. 9, 895172 (2022).

Tan, K., Ye, Y. Y., Du, P. J. & Zhang, Q. Q. Estimation of heavy metal concentrations in reclaimed mining soils using reflectance spectroscopy. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 34(12), 3317–3322 (2014).

Guan, X., Wang, S., Gao, Z. & Lv, Y. Dynamic prediction of soil salinization in an irrigation district based on the support vector machine. Math. Comput. Model. 58(3–4), 719–724 (2013).

Wang, J., Wang, W., Hu, Y., Tian, S. & Liu, D. Soil moisture and salinity inversion based on new remote sensing index and neural network at a salina-alkaline wetland. Water 13(19), 2762 (2021).

Kaplan, G. & Avdan, U. Evaluating the utilization of the red edge and radar bands from sentinel sensors for wetland classification. Catena 178, 109–119 (2019).

Sidike, A., Zhao, S. & Wen, Y. Estimating soil salinity in Pingluo County of China using QuickBird data and soil reflectance spectra. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinform. 2014, 26156–26175 (2014).

Fan, X. et al. Soil Salinity retrieval from advanced multi-spectral sensor with partial least square regression. Remote Sensing 7(1), 488–511 (2015).

Taghadosi, M. M., Hasanlou, M. & Eftekhari, K. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Eur. J. Remote Sensing 52(1), 138–154 (2019).

Lobell, D. B. et al. Regional-scale assessment of soil salinity in the Red River Valley using multi-year MODIS EVI and NDVI. J. Environ. Qual. 39(1), 35–41 (2010).

Ma, G., Ding, J., Han, L. & Zhang, Z. Digital mapping of soil salinization in arid area wetland based on variable optimized selection and machine learning. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng 36, 124–131 (2020).

Tai X. Soil Salinity Monitoring Model on UAV Multi Spectral Remote Sensing Vegetation Cover[D]. Northwest Agricultural and Forestry University, 2022.

Bian, L., Wang, J., Guo, B., Cheng, K. & Wei, H. Remote sensing extraction of soil salinity in Yellow River Delta Kenli County based on feature space. Remote Sensing Technol. Appl. 35(1), 211–218 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Environmental sensitive variable optimization and machine learning algorithm using in soil salt prediction at oasis. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng 34, 102–110 (2018).

Guo, Y. et al. Integrating spectral and textural information for identifying the tasseling date of summer maize using UAV based RGB images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinform. 102, 102435 (2021).

Morellos, A. et al. Machine learning based prediction of soil total nitrogen, organic carbon and moisture content by using VIS-NIR spectroscopy. Biosyst. Eng. 152, 104–116 (2016).

Cui, X. et al. Estimating soil salinity under sunflower cover in the Hetao Irrigation District based on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing. Land Degrad. Dev. 34(1), 84–97 (2023).

Shieh, H. L. & Kuo, C. C. A reduced data set method for support vector regression. Exp. Syst. Appl. 37(12), 7781–7787 (2010).

Zhu, C., Ding, J., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Z. Exploring the potential of UAV hyperspectral image for estimating soil salinity: Effects of optimal band combination algorithm and random forest. Spectrochimica Acta Part A 279, 121416 (2022).

Yu, X., Chang, C., Song, J., Zhuge, Y. & Wang, A. Precise monitoring of soil salinity in China’s Yellow River Delta using UAV-borne multispectral imagery and a soil salinity retrieval index. Sensors 22(2), 546 (2022).

Zhang, Z. T. et al. UAV multispectral remote sensing soil salinity inversion based on different fractional vegetation coverages. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 53(08), 220–230 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Agricultural Water and Hydrological Ecology Experiment Station, Yangzhou University, for providing the experimental facilities.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52379049, 52209071), the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (Yangzhou University) (No. SJCX23_1945), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023T160552, 2020M671623), “Chunhui Plan” Cooperative Scientific Research Project of Ministry of Education of China (HZKY20220115), the “Blue Project” of Yangzhou University and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z.; methodology, Z.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, M.D. and M.T.; formal analysis, Z.L.; resources, M.D.; data curation, M.D. and R.L.; Writing—original preparation, Z.L.; Writing—review and editing, C.Z. and M.T.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, C.Z. and S.F.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, C.Z. and S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, Z., Deng, M., Tang, M. et al. Estimating soil profile salinity under vegetation cover based on UAV multi-source remote sensing. Sci Rep 15, 2713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82868-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82868-9