Abstract

Worldwide, congenital deafness and pigmentation disorders impact millions with their diverse manifestations, and among these genetic conditions, mutations in the Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF: OMIM#156845) gene are notable for their profound effects on melanocyte development and auditory functions. This study reports a novel porcupine model exhibiting spontaneous deafness and pigmentation abnormalities reminiscent of human Waardenburg Syndrome Type 2 (WS2: OMIM#193510). Through phenotypic characterization, including coat color, skin, eye morphology, and auditory brainstem response (ABR) assessments, we identified hypopigmentation and complete deafness in mutant porcupines. To pinpoint the genetic basis, a breeding program was established, and Bulk Segregant Analysis (BSA) combined with RNA sequencing was conducted. Primers based on the identified candidate genes were designed for PCR amplification, followed by verification through Sanger sequencing. Through BSA analysis, we identified a total of 88 SNP and 336 InDel candidate sites. By annotating the Mitf gene, we obtained four unique transcript sequences. The SNP and InDel sites within the porcupine Mitf gene sequence, identified through BSA screening, were analyzed in conjunction with the gene’s annotation results. This analysis revealed a specific mutation site, Mitf c.875_877delGAA p. (Arg217del), which was subsequently verified by Sanger sequencing. This naturally occurring Mitf mutation in porcupines provides a valuable model for studying the mechanisms underlying WS2 and exploring potential therapeutic strategies for deafness and pigmentation-related disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deafness, defined by a partial or complete inability to hear, poses a substantial global health issue and is a primary factor in contributing to years lived with disability, negatively impacting overall well-being1,2. According to projections by the World Health Organization (WHO), the number of individuals affected by disabling hearing impairment, which stood at 466 million in 2018, is expected to increase to 630 million by 2030 and surpass 900 million by 20503. Hereditary deafness, often accompanied by pigmentary disorders, represents a unique yet significant group of genetic conditions where the causal connection intertwines pigmentation with auditory function. WS2 is a genetic condition characterized by congenital hearing loss and pigmentation abnormalities. These manifestations are primarily linked to mutations in the MITF gene, which plays a crucial role in the development and differentiation of melanocytes and auditory neuroepithelia in the inner ear. Common phenotypic features include: sensorineural hearing loss varying from moderate to profound, patchy absence of pigmentation, heterochromia iridum (different colored eyes), and early graying of hair, variable ocular anomalies such as microphthalmia (abnormally small eyes) or iris hypoplasia (underdevelopment of the colored part of the eye)4. The incidence of this syndrome ranges between 1 in 42,000 to 1 in 50,000 individuals5, signifying its rarity. Although the precise mechanisms linking pigmentary disorders to deafness remain to be fully clarified, research suggests a significant intersection of the pathways involved in both pigment production and auditory function6.

WS2 exhibits a broad spectrum of genetic variability7, with most currently identified associated genes having a direct link to melanocyte migration, as well as to the development of neural crest and inner ear cells. Genetic factors underlying the conditions are manifold, with mutations in a cohort of genes including, but not limited to, PAX3, EDNRB, SOX10, and the MITF known to play pivotal roles8,9,10,11. Among these, the gene known as MITF, a member of the MYC superfamily that is mutated in 10–15% of WS2, is renowned as a pivotal regulator that orchestrates the development, functionality, and preservation of melanocytes12. Given the MITF gene’s importance and complexity, studying animal models with mutations in this gene is a crucial approach to elucidate its function and the pathogenesis of related diseases when mutations arise.

The BSA method, also known as cluster separation analysis or mixed group analysis, involves selecting parents with extreme phenotypic differences to construct a family for the target trait. Whole genome resequencing is then performed on two mixed pools created by mixing DNA from the two parents and the offspring that exhibit extreme phenotypic characteristics of the family. The DNA difference fragments detected between the two mixed pools are candidate regions. By annotating the genes within these regions, one can further pinpoint genes or markers related to the target trait. This method allows for the quick localization of a single trait on the genome. At present, the BSA method is widely used in animals, plants, and other species. For example, BSA-Seq has been used to identify candidate genes for cold tolerance at the booting stage of cold-region rice and to identify the main loci for resistance to the root-knot nematode on chromosome 613,14.

In our study, porcupines with mutations in the Mitf gene exhibited distinct phenotypic similarities with human WS2, including: all mutant porcupines showed complete hearing loss, akin to the sensorineural hearing loss seen in WS215. The porcupines demonstrated characteristic pigmentation defects, such as regions of hypo-pigmentation on the skin and fur. Microphthalmia, or abnormally small eyes, was prevalent among homozygous mutant porcupines, closely mirroring another key feature of WS216. Based on the establishment of a mutant porcupine model family, this study initially identified its phenotype through observations of coat color, skin, eyes, and hearing. Subsequently, we employed the BSA method combined with transcriptome sequencing to precisely locate the pathogenic gene and mutation site, confirming the mutation through Sanger sequencing.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

All animal study protocols were conducted in strict adherence to the Ethical Management of Laboratory Animal Welfare standards established by Zunyi Medical University. The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Center of Zunyi Medical University (Approval number: [2016] 2–059) and was carried out in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

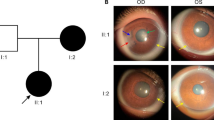

Breeding of the porcupine family line

The porcupines used in the experiment were acquired from Muxinyuan Ecological Agriculture Development Co., Ltd., situated in Suiyang County, Zunyi City, Guizhou Province. The facility holds a wild animal breeding license numbered Suidong 2013 Xunfan (010). For the experiment, we utilized 4 heterozygous mutant male porcupines and 8 wild type female porcupines as the F0 generation. These porcupines were paired for breeding in a 1 male to 2 female ratio to establish the family lineage. The offspring, comprising the F1 generation, were initially screened for traits, and those partially showing albino phenotypes in coat, skin, and sclera color were identified as heterozygous mutants. By interbreeding the F1 generation’s heterozygous mutant individuals, we obtained an F2 generation for further analysis. The offspring of F2 generation were preliminarily screened, and the offspring showing complete albinism in their coat, skin, and sclera, as well as a microphthalmia phenotype were identified as homozygous mutant. A partial genetic pedigree of the porcupine family is shown in Fig. 1.

Collection of skin and inner ear tissues

Specimens were collected from 3 wild type porcupines, 3 heterozygous mutant porcupines, and 3 homozygous mutant porcupines. These animals were anesthetized with intramuscular injections of a specialized anesthetic mixture, known as ‘Su-Mian-Xin,’ provided by Dunhua Shengda Animal Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Dunhua, China. The primary active ingredient in the mixture is chlorpromazine hydrochloride, with a concentration of 2 ml:0.1 g, and it was administered at a dosage of 0.1 ml/kg. Following anesthesia, the subjects were promptly decapitated, and with ear notchers, we excised 2 × 2 cm sections of auricle skin tissue. We then removed the surface hair with a scalpel and submerged the tissue samples in 4% paraformaldehyde before placing them in a 4 °C refrigerator overnight for fixation.

Histology

The fixed tissues were rinsed in running water for 24 h to wash away fixative residues, followed by dehydration through a graded ethanol series (70%, 80% and 90%) to remove moisture. Subsequently, the tissues were cleared in xylene, rendering them transparent and ready for paraffin embedding. The tissue blocks were then sectioned at 4 μm thickness using a microtome. These paraffin sections, placed on glass slides, were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a descending ethanol series. The sections were sequentially stained with hematoxylin, to target the nuclei, and eosin, to stain the cytoplasm and extracellular components. Following staining, the slides were dehydrated using an ascending ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and then mounted with a xylene-based adhesive under a coverslip. Finally, pigment deposition was observed under a microscope.

Auditory brainstem response (ABR) assessment

ABR assessments were performed on wild type, heterozygous mutant, and homozygous mutant porcupines using an auditory evoked potential system (SmartEP M010000, Intelligent Hearing Systems, USA) within a soundproofed and shielded room. Each group included three 4-month-old male porcupines. Silver needle electrodes were utilized where the recording electrode was positioned along the line connecting the vertex of the porcupine’s skull to the anterior edge of both ears. The reference electrode was inserted into the earlobe, while the ground electrode was secured at the tip of the snout. Stimulus tones comprised of brief clicks and short pure tones (tone burst) at frequencies of 0.5 kHz, 1 kHz, 4 kHz, 8 kHz, 16 kHz, and 32 kHz. The sound was emitted at a distance of 2 cm from the porcupine’s ear, with each acoustic stimulus lasting 4 ms and subjected to a band-pass filter range of 300–3000 Hz. The short-tone stimulus operated at 12.1 beats/s with a duration of 0.1 ms, followed by a 4 ms short tone burst with rise and fall times of 0.5 ms. The evoked response potentials were amplified by a factor of 10,000 across an average of 1024 superimpositions. The apex stimulus sound intensity reached 120 dB SPL and was methodically attenuated from 120 dB SPL in decrements of 10 dB SPL until a consistent ABR waveform could no longer be elicited. The intensity was then increased in increments of 5 dB SPL to determine the threshold, which was defined as the lowest stimulus intensity at which consistent ABR waveforms were perceptible. This process was repeated three times, and the mean value was recorded as the ABR threshold for the porcupine17.

DNA mixing pool construction

The experiment divided subjects into mutant and normal groups based on their phenotypic traits. For the mutant group, auricular skin tissue samples were collected from 13 heterozygous mutant porcupines; for the normal group, samples were taken from 18 wild type individuals. Additionally, a single F0 generation mutant parent pool was established, consisting of DNA from two male porcupine of the F0 generation. Each sample was placed in an individually labeled, sealed sampling tube. Tissue DNA was extracted using the Genomic DNA Extraction and Detection Kit from Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Lot: U9022), following the provided instructions meticulously. The samples were then sent to Beijing Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. for sequencing.

BSA library construction and sequencing

A total amount of 1.5 µg DNA per sample was used as input material for the DNA sample preparations. Sequencing libraries were generated using Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample preparation Kit following manufacturer’s recommendations and index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, the DNA sample was fragmented by sonication to a size of 350 bp, then DNA fragments were end polished, A-tailed, and ligated with the full-length adapter for Illumina sequencing with further PCR amplification. At last, PCR products were purified (AMPure XP system) and libraries were analyzed for size distribution by Agilent2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified using real-time PCR. These libraries constructed above were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq4000 platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated with insert size around 350 bp.

Mapping to reference genome

We first performed a quality assessment of the raw sequencing data, which included analyzing the error rate distribution and nucleotide content. Then, we removed the adapter sequences and filtered out reads of low quality and those with an N ratio (indicating bases that cannot be determined) greater than 10%. This process yielded clean reads suitable for subsequent analysis. The clean reads are mapped onto the reference genome (Mus musculus) employing the BWA software (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner)18. Furthermore, the command “rmdup” from SAMtools19 software is utilized to eliminate possible PCR duplicates. In scenarios where multiple read pairs share identical external coordinates, only the pair exhibiting the highest mapping quality is preserved. The basic information of the reference genome is shown in Table 1.

SNP and InDel detection and annotation

The variant identification process across all samples was performed using the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) software’s Unified Genotyper feature20. For SNPs, we applied the Variant Filtration parameter within GATK with the following configuration: --filter Expression set to “QD < 4.0 || FS > 60.0 || MQ < 40.0”, -G_filter to “GQ < 20”, and –cluster WindowSize specified as 4.InDels were filtered using Variant Filtration parameters (settings: --filter Expression “QD < 4.0 || FS > 200.0 || Read PosRankSum < -20.0 || Inbreeding Coeff < -0.8”). ANNOVAR21, an effective software tool, annotated SNPs or InDels based on GFF3 files of the reference genome, given its powerful annotation capabilities and international recognition, so we used it to annotate the results of our assay.

SNP and InDel calculations

We used one parent’s genotype (1f1) as a reference to statistically analyze the number of reads corresponding to this genotype or others within the offspring pools. This method involves using sequencing reads to enumerate the nucleotides at each genomic position. It then compares these nucleotides to the reference genome. For a given site, we count the reads in the progeny pool that match or differ from the reference genome. The SNP-index is then calculated by dividing the number of differing reads by the total number of reads at that site, providing a measure of variation at that locus. In this context, a completely identical SNP-index equals 0, while a completely different SNP-index equals 1. The calculation of the InDel-index followed a similar methodology to that of the SNP-index.

To mitigate background noise, sequencing and alignment errors, and improve gene positioning efficiency, we meticulously screened and filtered SNP/InDel and SNP/InDel-index data. The screening and filtering process adhered to the following criteria:

-

1.

Screening for markers indicating parental homozygosity within the parent population.

-

2.

Excluding sites with an SNP/InDel-index less than 0.3 and SNP depth below 7 in both offspring groups.

-

3.

Filtering out sites with a missing SNP-index in any offspring group.

Differential analysis of SNP and InDel

To visualize the differences between the two offspring pools, the △(SNP-index) = SNP-index (S2)-SNP-index (S1) was calculated. We set the window to 1 Mb and the step size to 1 kb, calculating the mean value of △(SNP-index) to assess the △(SNP-index) distribution. Alongside the population type and the number of offspring mixing pools, a 1,000 permutation test was conducted22. The calculation of the △(InDel-index) followed a similar methodology to that of the SNP-index.

Identify candidate genes based on SNP and InDel

In order not to ignore the influence of micro-effective quantitative trait loci (QTLs), SNP and InDel loci with significant differences in their respective indices between two offspring were selected across the genome. That is, sites where the SNP index or InDel index of offspring 2 are close to 1.0 are selected, and sites where the SNP index or InDel index of offspring 1 are close to 0.0 are selected. For these candidate polymorphic loci, annotation results were extracted using ANNOVAR, prioritizing genes containing loci that resulted in termination loss, termination gain, nonsynonymous mutations, or alternative splicing as candidate genes.

Transcriptome sequencing

The auricle skin tissue from adult wild type porcupines was sized, washed thrice with PBS, and then promptly cut, placed into a sampling tube, and stored in liquid nitrogen. This tissue was subsequently sent to Shanghai Zhongke New Life Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for transcriptome sequencing. Total RNA from the sample was extracted using the TRIzol method. After passing the quality test, mRNA was enriched with magnetic beads containing Oligo(dT), and Fragmentation Buffer was added to cleave the mRNA into short fragments of 200–300 bp. The RNA sample was then used as a template to synthesize the first strand of cDNA using 6-base random primers and reverse transcriptase. Subsequently, the second strand of cDNA was synthesized using the first strand as a template. The double-stranded cDNA was purified using AMPure XP beads. This purified double-stranded cDNA underwent end repair, A-tailing, and ligation with sequencing adapters. The fragment size was selected with AMPure XP beads, followed by PCR amplification to generate the final cDNA library. After the insert fragment length and the effective concentration of the library had been tested and met the qualifications, sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq platform. Raw image data procured from Illumina’s high-throughput sequencing undergoes base calling with CASAVA, transforming them into sequenced reads.

Transcript splicing and Mitf gene annotation

The sequencing data were then subjected to quality assessment, including error rate distribution and nucleotide content analysis. Adapter sequences were trimmed, and reads with low quality and undetermined bases (N) were filtered out to obtain clean reads for subsequent analyses23. Using Trinity software, the gold standard for assembling Illumina short-read sequences, we constructed reference sequences from clean reads. This process, comprising the Inchworm, Chrysalis, and Butterfly stages24, resulted in the assembled transcript sequences being saved in the FASTA format. Since the porcupine genome sequence has not been annotated, we first annotated the candidate genes for porcupine pathogenicity. We searched for the human MITF gene sequence information on Genbank, then compared the spliced porcupine Mitf transcript sequence with the human MITF gene sequence. The region on the porcupine Mitf gene with the highest sequence homology to the human MITF gene exon sequence was defined as the porcupine Mitf gene exon region, resulting in the annotation of the porcupine Mitf gene.

Localization of candidate mutation sites in Mitf gene

In this study, we annotated the porcupine Mitf gene and screened for candidate mutation sites using the BSA method. To conduct a detailed examination, 23 porcupines from the family were selected, comprising 17 heterozygous mutants and 6 wild types, all of whom provided ear skin tissue samples. After extracting DNA from these samples, we designed specific primers flanking the mutation sites previously identified in the Mitf gene. Sanger sequencing, along with co-segregation analysis, confirmed the link between phenotype and genotype. The primer sequences used were as follows: Forward: 5’TTTTCCTGACCTGGGTAACGTTC3’ and Reverse: 5’AATCTGTTTGCCAAGGAATCTC3’.

Results

Generation breeding results and animal phenotype

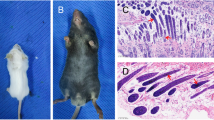

In our study, we obtained a total of 38 F1 individuals, comprising 21 heterozygous mutants and 17 individuals exhibiting the wild type phenotype. Subsequently, we intercrossed the dominant heterozygotes from the F1 generation to produce 4 F2 individuals, which included 3 homozygous mutants and 1 individual with the wild type phenotype. Wild type porcupines possess a coat, skin, and sclera of a brownish-black color (Fig. 2A). In contrast, heterozygous mutant porcupines display albinism in their spines and sclera, alongside large albino patches on their head skin (Fig. 2B). Homozygous mutant porcupines exhibit comprehensive albinism encompassing their coat, spines, skin, and sclera, as well as microphthalmia (Fig. 2C). Histological evaluation using hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of skin tissue sections revealed that the melanin granules in wild type porcupines were prominently located in the basal layer of the epidermis, demonstrating abundant distribution and fullness (Fig. 2D). In contrast, the melanin granules in heterozygous mutant phenotype porcupines were sparsely distributed and considerably smaller in size (Fig. 2E). Almost no melanin particles are found in homozygous porcupines (Fig. 2F).

Different traits of porcupine. (A) Wild type porcupine. (B) Heterozygous mutant porcupine. (C) Homozygous mutant porcupine. (D) HE staining results of wild type porcupine. (E) HE staining results of heterozygous mutant porcupines. (F) HE staining results of homozygous mutant porcupines. The red arrows indicate melanocytes.

ABR assessment results

In auditory tests, wild type porcupines produced distinguishable and consistent ABR waveforms across a complete frequency range of 0.5 kHz to 32 kHz, with Wave I cochlear elicitation at an 80 dB threshold (Fig. 3A). Conversely, heterozygous and homozygous mutant phenotype porcupines fail to generate recognizable ABR waveforms at any frequency, even at maximum sound pressure of 120 dB (Fig. 3B and C).

Quality of sequencing data

This BSA sequencing run generated a total of 157.524G of Raw data, and after filtering, 156.833G of clean data were obtained. The Raw data for each sample ranged between 49723.477 M and 56402.203 M, with high sequencing quality (Q20 ≥ 96.34%, Q30 ≥ 90.99%) and a GC content between 42.35% and 43.39% (Supplementary Table 1). By comparing the reads to the reference genome, the alignment rate for all samples is observed to range between 98.61% and 99.52%. The average coverage depth of the reference genome spans from 15.77X to 18.74X, with coverage at 1X exceeding 92.94% and coverage at 4X exceeding 88.55%. These alignment results are within normal parameters and are suitable for subsequent variant detection and related analyses (Table 2). The sequencing depth distribution is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

SNP and InDel site statistics

Samtools software was utilized to identify sample loci, yielding a total of 30,931,493 SNP and 3,357,842 InDel sites. ANNOVAR was employed for annotating the detection results, resulting in 22,901,283 conversion SNP sites, 8,030,156 transversion SNP sites, 1,498,425 insertion InDel sites, and 1,859,417 deletion InDel sites (Table 3).

SNP and InDel index distribution

To minimize background noise and sequencing errors, SNP-index and InDel-index filtering was applied, to yield 5,225,858 SNP and 433,134 InDel polymorphic marker sites. The distribution of these sites across chromosomes was mapped with a window size of 1 Mb and step size of 1 kb, calculating average SNP and InDel index values per window (Fig. 4). This analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the distribution of SNP, InDel, and the combined all-index across the genome in offspring pools.

Chromosome Index Distribution among Two Offspring Sets. (A) SNP-index distribution. (B) InDel-index distribution. Points represent SNP or InDel loci; the horizontal axis shows the window midpoint, and the vertical axis represents index values. Different colors differentiate chromosomes, with the black line indicates the average index value.

Differential analysis of SNP/InDel index

We also chose 1 Mb as the window and 1 kb as the step size, and calculated the average value of ∆(SNP/InDel-index) in each window to reflect the ∆(SNP/InDel-index) distribution. Differential chromosome indices illustrate the variance in SNP (Fig. 5A), InDel indices (Fig. 5B). A total of 3,797 SNP and 545 InDel sites were identified with a confidence level of 95% and 99% respectively after performing a permutation test.

Candidate polymorphic marker sites

Based on ANNOVAR annotation results, we identified candidate genes at loci associated with stop loss, stop gain, non-synonymous mutations, or alternative splicing. A total of 424 polymorphic markers were identified, including 88 SNP candidates and 336 InDel candidates (Table 4).

Illumina sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly

We obtained approximately 6G of raw data through Illumina high-throughput sequencing, and the summary statistics are shown in Table 5. Using Trinity software to assemble high-quality reads de novo, the length of the obtained transcripts ranged from 180 to 27,668 bp, with an average length of 973 bp and an N50 of 2,186 bp. For intuitive representation, the results were displayed as bar charts, showcasing the length distribution of transcripts and unigene sequences (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Mitf mutation site screening

In this study, we found that the phenotypic characteristics of the mutant porcupine were very similar to those of human WS2, and the homozygous mutant individuals exhibited typical microphthalmia phenotypic characteristics. We speculated that the pathogenic gene in this porcupine family is likely to be Mitf. So we selected Mitf as the candidate gene for porcupine pathogenicity and annotated it. Based on the reference-free transcriptome sequencing library, we extracted a total of 4 non-repetitive porcupine Mitf gene transcripts (uploaded to GenBank, accession numbers: MW840376, MW840377, MW840378, and MW840379). We analyzed the human MITF-M transcript isoform (NM_000248.4) included in the GenBank database, which contains a total of 9 exons, and compared the 4 porcupine transcripts with these exons. The comparison exhibited a similarity above 98% except for exons 2 and 6. Comparison of exon lengths between porcupine and human MITF-M transcript isoforms is shown in Supplementary Table 2. Through BLAST alignment, the porcupine Mitf gene was located in the reference genome fragment PVJO010006423.1. Based on the experimental results of the BSA method, SNP and InDel sites on the PVJO010006423.1 fragment were searched, and 0 SNP and 7 InDel sites were screened. The Mitf regions where these InDel sites are located were annotated (Table 6). As can be seen from Table 6, only the deletion mutation of three bases (TTC) at position 77,566 on the PVJO010006423.1 fragment is in the exon region.

Sanger sequencing validation

Sanger sequencing of 23 individuals (17 heterozygous mutants and 6 wild types) confirmed this deletion, with mutant individuals lacking GAA at the locus and exhibiting a double peak, indicative of a heterozygous pattern (Fig. 6). In this study, by consulting the human deafness-related gene mutation database available at http://grenada.lumc.nl/LOVD3/WS, we matched the mutation site identified in the albino deaf porcupine’s Mitf gene. The findings revealed that the specific Mitf gene mutation observed in the albino deaf porcupine was Mitf c.875_877delGAA p. (Arg217del). This mutation, deleting arginine at position 217 (MITF-M R217del), occurs in the nuclear localization signal (NLS) region of the human MITF-M, as reported by Chen et al.25.

Discussion

Congenital deafness and pigmentary abnormalities represent significant global health challenges, impacting the quality of life for millions1. The MITF gene is crucial for the development, differentiation, survival, and the synthesis and transport mechanisms within melanocytes. By controlling melanin production through the regulation of enzymes related to its synthesis, MITF plays a pivotal role in determining the pigment of skin, hair, and eyes. WS2, which is characterized by deafness and pigmentary abnormalities, is often caused by mutations in the MITF gene26. Mutations in the MITF gene compromise melanocyte functionality, thereby significantly reducing pigment production. Furthermore, such mutations can interfere with inner ear development, compromising auditory cell function and ultimately causing congenital deafness. This study accurately identified the pathogenic gene and mutation site in the porcupine model of spontaneous dyschromatosis deafness as Mitf c.875_877delGAA p. (Arg217del). This further confirmed that the MITF gene plays an important role in the manifestation of WS2 phenotypes.

The observed phenotypic parallels between the mutant porcupines and human patients with WS2 can be attributed to the conserved role of MITF across species. The MITF gene is vital for melanocyte development and function, and its disruption leads to similar outcomes in different organisms. The mutation in the porcupine Mitf gene affects the nuclear localization signal (NLS), a domain essential for the transcription factor’s activity. This disruption parallels mutations in human MITF that similarly impact the protein’s function and result in WS227. Given the striking phenotypic similarities and common genetic underpinnings, the porcupine model provides a valuable resource for studying WS2. Currently, more than 400 animal models of hereditary deafness have been reported, mainly including small rodents such as mice and guinea pigs. From Paula Hertwig’s28 discovery of the first Mitf mutant mouse in 1942 to the construction of Mitf +/− gene knockout mice by Shuxian Han29 through genetic engineering, homozygous mutant mice exhibit white or light-colored coats due to the loss of melanocytes and present with sensorineural deafness, akin to the human phenotype. However, employing mice for research into deafness-related diseases inevitably faces limitations. Although the auditory structure of mice shares a certain degree of similarity with humans, their auditory system requires postnatal development to reach full maturity, diverging significantly from that of humans30. Consequently, certain diseases related to inner ear development cannot be replicated in mouse models31. The current big animal models for hereditary deafness are quite lacking. Ning Li32 has developed a porcine model of Vitiligo-deafness with Mitf mutations, the albino pigs showed severe hearing loss, depigmentation, and a pale iris, which holds considerable application potential for the development of otological techniques and clinical translational research. However, the model exhibits recessive inheritance, and the mutation sites have not been reported in human cases of WS. The Mitf c.875_877delGAA p. (Arg217del) spontaneous mutation deafness porcupine model identified in this study can better reflect the real impact of mutations in the natural environment, simulate the natural process of human disease development, and reveal the complex gene-environment interactions associated with mutations. This model provides important tools and materials for studying the pathogenic mechanisms, clinical treatment, and medical device evaluation of the corresponding human hereditary deafness. In contrast, models constructed by genetic engineering technology are artificially designed under laboratory control conditions and may lack certain natural regulatory factors present in spontaneous models.

At present, the genetic landscapes of certain experimental animals (such as tree shrews, gerbils, Eastern European voles) and specific breeds (such as foxes, sika deer, bamboo rats) remain opaque, presenting challenges to annotation efforts. Conventional methodologies aimed at pinpointing genes associated with specific traits in these entities may face hurdles. This investigation, through the integration of BSA-seq and RNA-seq approaches, successfully identified the disease-causing gene linked to autosomal dominant pigmentary dyschromatosis syndrome-type deafness in porcupines. This accomplishment provides a valuable reference for uncovering pathogenic genes within distinctive animal species.

Conclusions

This study successfully established a porcupine family with spontaneous pigmentary abnormality syndrome type deafness; phenotypic identification showed that the phenotypic characteristics of this model are very similar to the disease manifestations of human WS2; at the same time, the pathogenic gene and mutation site were accurately identified as Mitf c.875_877delGAA p. (Arg217del). The research results can provide a theoretical basis and reference for studying the molecular pathogenic mechanism of the corresponding human hereditary deafness disease.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [SZ], upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BSA:

-

Bulked Sergeant Analysis

- InDel:

-

Insertion-Deletion

- MITF:

-

Microphthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor

- SNP:

-

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- WS:

-

Waardenburg Syndrome

References

Olusanya, B. O., Neumann, K. J. & Saunders, J. E. The global burden of disabling hearing impairment: a call to action. Bull. World Health Organ. 92, 367–373 (2014).

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

Chadha, S. & Cieza, A. World Health Organization and Its Initiative for Ear and Hearing Care. Otolaryngol. Clin. North. Am. 51, 535–542 (2018).

Pingault, V. et al. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 31, 391–406 (2010).

Shah, K. N. et al. White forelock, pigmentary disorder of irides, and long segment Hirschsprung disease: possible variant of Waardenburg syndrome. J. Pediatr. 99, 432–435 (1981).

Song, J. et al. Hearing loss in Waardenburg syndrome: a systematic review. Clin. Genet. 89, 416–425 (2016).

Lee, C. Y. et al. Identification of nine novel variants across PAX3, SOX10, EDNRB, and MITF genes in Waardenburg syndrome with next-generation sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 10, e2082 (2022).

Boudjadi, S., Chatterjee, B., Sun, W., Vemu, P. & Barr, F. G. The expression and function of PAX3 in development and disease. Gene 666, 145–157 (2018).

Issa, S. et al. EDNRB mutations cause Waardenburg syndrome type II in the heterozygous state. Hum. Mutat. 38, 581–593 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. Two novel mutations of PAX3 and SOX10 were characterized as genetic causes of Waardenburg Syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8, e1217 (2020).

Yang, T. et al. Double heterozygous mutations of MITF and PAX3 result in Waardenburg syndrome with increased penetrance in pigmentary defects. Clin. Genet. 83, 78–82 (2013).

Pogenberg, V. et al. Restricted leucine zipper dimerization and specificity of DNA recognition of the melanocyte master regulator MITF. Genes Dev. 26, 2647–2658 (2012).

Kaur, G. et al. BSA-seq Identifies a Major Locus on Chromosome 6 for Root-Knot Nematode (Meloidogyne graminicola) Resistance From Oryza glaberrima. Front. Genet. 13, 871833 (2022).

Guo, Z. et al. Identification of candidate genes controlling chilling tolerance of rice in the cold region at the booting stage by BSA-Seq and RNA-Seq. R Soc. Open. Sci. 7, 201081 (2020).

Levy, C., Khaled, M. & Fisher, D. E. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol. Med. 12, 406–414 (2006).

Smith, S. D., Kelley, P. M., Kenyon, J. B. & Hoover, D. Tietz syndrome (hypopigmentation/deafness) caused by mutation of MITF. J. Med. Genet. 37, 446–448 (2000).

Liberman, M. C. et al. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature 419, 300–304 (2002).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

McKenna, A. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010).

Takagi, H. et al. QTL-seq: rapid mapping of quantitative trait loci in rice by whole genome resequencing of DNA from two bulked populations. Plant. J. 74, 174–183 (2013).

Kechin, A., Boyarskikh, U., Kel, A., Filipenko, M. & cutPrimers A New Tool for Accurate Cutting of Primers from Reads of Targeted Next Generation Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 24, 1138–1143 (2017).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494–1512 (2013).

Chen, H. et al. Novel mutations of PAX3, MITF, and SOX10 genes in Chinese patients with type I or type II Waardenburg syndrome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 397, 70–74 (2010).

Tassabehji, M., Newton, V. E. & Read, A. P. Waardenburg syndrome type 2 caused by mutations in the human microphthalmia (MITF) gene. Nat. Genet. 8, 251–255 (1994).

N, B. et al. Interaction among SOX10, PAX3 and MITF, three genes altered in Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, (2000).

Green, M. C. et al. A revision of the standardized genetic nomenclature for mice. J. Hered. 54, 159–162 (1963).

Han, S. et al. MITF protects against oxidative damage-induced retinal degeneration by regulating the NRF2 pathway in the retinal pigment epithelium. Redox Biol. 34, 101537 (2020).

Morell, R. J. et al. Noncoding Microdeletion in Mouse Hgf Disrupts Neural Crest Migration into the Stria Vascularis, Reduces the Endocochlear Potential, and Suggests the Neuropathology for Human Nonsyndromic Deafness DFNB39. J Neurosci. 40, 2976–2992 (2020).

Walters, B. J. & Zuo, J. Postnatal development, maturation and aging in the mouse cochlea and their effects on hair cell regeneration. Hear. Res. 297, 68–83 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. A de novo silencer causes elimination of MITF-M expression and profound hearing loss in pigs. BMC Biol. 14, 52 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the BSA sequencing services provided by Beijing Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. We also thank Shanghai Zhongke New Life Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for their transcriptome sequencing services.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81660176) for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KL: Writing – review, editing; CH: Data accessibility; HL: Bioinformatics-related data analysis; KT: Experimental porcupine feeding management, animal experiment operation; SZ: Experimental design, data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K., Huo, C., Long, H. et al. Identification of the Mitf gene mutation causing congenital deafness and pigmentation disorders in porcupines using BSA-Seq. Sci Rep 14, 31480 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82975-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-82975-7