Abstract

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for various diseases, but the mechanisms through which it influences disease development remain unclear. Using Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, we examined the causal relationship between BMI, 249 metabolic traits, and cholelithiasis. BMI data were obtained from four sources, and cholelithiasis data were from two distinct datasets. We analyzed the direct effect of BMI on cholelithiasis and identified key metabolic mediators. BMI was found to be positively associated with the risk of cholelithiasis across all datasets analyzed. A total of 176 metabolites were identified to be significantly associated with BMI, including amino acids, cholesterol esters, free cholesterol, triglycerides, and phospholipids. Among these, 49 metabolites were identified as mediators in the BMI-cholelithiasis relationship. Specifically, fatty acid levels, cholesteryl esters, phospholipids, triglycerides, and free cholesterol were key mediators in this relationship, with mediation proportions ranging from − 2.38–7.14%. This study provides robust evidence that BMI significantly impacts metabolic biomarkers, which in turn affect the risk of cholelithiasis. These findings highlight the importance of managing BMI to mitigate metabolic dysfunction and reduce the risk of gallstone formation. Future research should explore the specific metabolic pathways involved to identify potential therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, in 2022, global obesity rates continued to rise, with 1 in 8 people living with obesity, as adult obesity more than doubled and adolescent obesity quadrupled since 1990, while 2.5 billion adults were overweight, including 890 million with obesity1. It is widely recognized that obesity is a risk factor for many diseases2,3,4,5; however, the mechanisms through which obesity influences disease development are not yet fully understood6,7. Metabolic biomarkers play a significant role in understanding the underlying mechanisms through which Body mass index (BMI) contributes to disease risk, particularly in the context of lipid metabolism and other metabolic pathways. Previous studies have established the link between BMI and certain metabolic traits, such as amino acids8,9 and cholesterol levels10, it remains unclear whether BMI can influence the risk of various diseases by affecting metabolite levels. BMI is a key indicator of obesity and has been widely associated with various metabolic disorders, including cholelithiasis (gallstone formation)11. Therefore, this study aims to explore whether BMI influences metabolite levels and, in turn, affects disease risk, specifically examining whether changes in BMI lead to alterations in blood metabolite profiles that contribute to the risk of developing cholelithiasis employing Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis. MR offers a robust approach to exploring the causal relationships between BMI, metabolic biomarkers, and cholelithiasis, as it minimizes confounding factors by using genetic variants as instrumental variables (IVs)12. This study’s exploration of BMI’s influence on metabolic biomarkers and its causal relationship with cholelithiasis could provide critical insights into the mechanisms driving obesity-related diseases. By identifying key metabolic mediators, this research could inform future therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating the metabolic dysfunctions associated with elevated BMI and reducing the risk of gallstone formation and other obesity-related conditions.

Methods

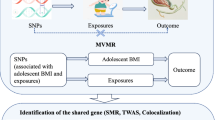

The analytical process of this study involves four key steps, as illustrated in Fig. 1. First, the direct effect of BMI on cholelithiasis is examined. Next, the relationship between BMI and 249 metabolic traits, considered potential mediating factors, is explored. The third step assesses how these metabolic traits influence cholelithiasis, evaluating their role as mediators. Finally, the fourth step identifies the significant mediators and calculates the proportion of the mediating effect relative to the total effect of BMI on cholelithiasis. This comprehensive approach sheds light on the pathways through which BMI influences cholelithiasis risk via metabolic mediators.

Analysis process flowchart. The analytical process of this study consists of 4 key steps, as depicted in the figure. Step 1 examines the impact of body mass index (BMI) on cholelithiasis (gallstones). Step 2 investigates the relationship between BMI and potential mediating factors (249 metabolic traits).Step 3 explores how these potential mediating factors influence cholelithiasis. Step 4 identifies the mediating factors and calculates the proportion of the mediating effect relative to the total effect.

Data sources

As presented in Table 1, this study incorporated BMI data from four different sources, 249 blood metabolites13, and cholelithiasis data from two distinct sources. To minimize sample overlap, BMI from the GIANT consortium (id: ieu-a-835) was chosen as the exposure, and cholelithiasis from the Finngen Biobank as the outcome, to examine whether BMI is associated with cholelithiasis and whether it influences cholelithiasis risk through its effects on blood metabolites. All data used in this study are available from the IEU OpenGWAS project14 and the FinnGen Biobank15. Since the MR analysis used publicly available data from open-access databases and involved no individual-level data, this research did not require ethics committee approval.

Criteria for choosing IVs

In MR study, IVs are used to determine causal relationships between an exposure and an outcome by minimizing confounding and avoiding reverse causality. IVs, typically single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), act as proxies for the exposure, helping to infer causality in a manner analogous to randomized controlled trials16. SNP selection was guided by several criteria, including a clumping window of 10,000 kb to account for physical proximity, strong linkage disequilibrium (r2 < 0.001), and a genome-wide significance threshold (p < 5 × 10− 8) to ensure robust associations with the exposure of interest. In all analyses, SNPs significantly associated with the outcome (p < 5 × 10− 8) were excluded to minimize bias and ensure adherence to the assumptions of Mendelian Randomization.

Statistical analysis

In this study, the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) approach is regarded as the primary method for determining causal relationships due to its superior performance compared to the other two methods (Weighted Median and MR-Egger method). To ensure the IVW method operates correctly, horizontal pleiotropy must be either balanced or negligible17. The MR-Egger method, which accommodates non-zero intercepts, was applied to evaluate horizontal pleiotropy. We applied false discovery rate (FDR)18 adjustments to lower the FDR during the multiple hypothesis testing procedure. Cochran’s Q-test was applied to assess heterogeneity; if the p-value was below 0.05, a random-effects IVW model was implemented, whereas a fixed-effects IVW model was applied if the p-value exceeded 0.05. The MR-PRESSO technique was implemented to detect outliers. All statistical analyses were conducted with R software (version 4.3.2) and the TwoSampleMR package19 (version 0.5.10).

Mediation analysis

Utilizing 249 metabolites as possible mediators, we conducted a two-step mediation MR analysis to investigate whether BMI-induced changes in blood metabolites could influence the risk of cholelithiasis. In the first step, we analyzed the relationship between BMI and 249 metabolic traits (β1). In the second step, we explored the association between these metabolic traits and cholelithiasis (β2). From the results, we identified potential mediators and calculated the mediation effect (β1*β2) as a proportion of the total effect of BMI on cholelithiasis.

Results

This study initially analyzed the impact of BMI from four different sources on cholelithiasis from two distinct datasets, with the results detailed in Supplementary Tables 1, 2. Across all analyses, BMI was consistently found to be positively associated with the risk of cholelithiasis. Subsequently, we evaluated the effects of BMI from four distinct sources on 249 metabolites, with the results detailed in Supplementary Tables 3–6. As shown in Supplementary Tables 7, to assess whether BMI from different sources exerted similar effects on metabolite levels, we identified 159 metabolites that were associated with all four BMI sources based on FDR-adjusted q-values. Through pairwise comparisons of their β-values, we observed that BMI exhibited consistent effects on these metabolites, with their levels either increasing or decreasing in response to higher BMI. Subsequently, we examined the effects of 249 metabolic traits on cholelithiasis from two different sources, with the results detailed in Supplementary Tables 8–9. To evaluate the impact of these metabolites on cholelithiasis across sources, we identified 54 metabolites associated with both cholelithiasis sources based on FDR-adjusted q-values, with the results shown in Supplementary Table 10. Pairwise comparisons of their β-values revealed that these metabolites consistently influenced cholelithiasis, with risk either increasing or decreasing in response to changes in metabolite concentrations. Based on a comparison of the relationships between BMI from four different sources, cholelithiasis from two different sources, and metabolites, we observed a high degree of consistency in the effects of BMI on metabolites as well as the effects of metabolites on cholelithiasis. To minimize sample overlap between the exposure, mediators, and outcomes, we selected BMI from the GIANT consortium (id: ieu-a-835) as the exposure and cholelithiasis from the Finngen Biobank as the outcome for subsequent analysis. In Table 2, we identified 176 metabolites associated with BMI from the GIANT consortium based on FDR-adjusted q-values. In Table 3, we identified 85 metabolites associated with cholelithiasis from FinnGen. In Table 4, we present 49 metabolites identified as mediators—BMI may influence the risk of cholelithiasis by affecting these metabolites. We categorized these metabolites into 10 groups, with the classification details available in Table S4 of the original publication13 on the 249 metabolites.

The impact of BMI on amino acids and cholelithiasis risk

This study included nine individual amino acids and one group of branched-chain amino acids, which are composed of multiple amino acids. As shown in Table 2, we found that BMI is associated with 8 of them, including phenylalanine levels (β = 0.116, p < 0.0001), glutamine levels (β= -0.100, p = 0.00237), glycine levels (β= -0.136, p < 0.0001), isoleucine levels (β = 0.118, p < 0.0001), total branched-chain amino acids (β = 0.150, p < 0.0001), leucine levels (β = 0.125, p < 0.0001), tyrosine levels (β = 0.153, p < 0.0001), and valine levels (β = 0.166, p < 0.0001). More information can be found in Table 2. As presented in Table 3, our analysis indicates a significant positive correlation between alanine levels and the risk of developing cholelithiasis (OR = 1.22, p = 0.00309). Although BMI affects amino acid levels, we found that this change has no impact on the risk of cholelithiasis.

The impact of BMI on cholesteryl ester levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 21 out of the 32 absolute and relative cholesterol ester levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study identified 15 cholesteryl esters levels associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 10 cholesterol ester levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from 2.29 to 5.48%.

The impact of BMI on free cholesterol levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 26 out of the 32 absolute and relative free cholesterol levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found 14 free cholesterol levels to be associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 9 free cholesterol levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from 2.23 to 4.36%.

The impact of BMI on cholesterol levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 27 out of the 35 absolute and relative cholesterol Levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 17 cholesterol levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 10 cholesterol Levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from 1.69 to 4.77%.

The impact of BMI on particle concentrations or sizes and cholelithiasis risk

As shown in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 12 out of three different particle sizes, as well as 18 absolute or relative particle concentrations included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 6 particle concentrations are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Furthermore, Table 4 reveals that only the concentration of large HDL particles mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with a mediation proportion of 4.11%.

The impact of BMI on triglyceride levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 28 out of the 32 absolute and relative triglyceride levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 6 triglyceride levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 5 triglyceride levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from − 2.09 to 4.87%.

The impact of BMI on phospholipid levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 24 out of the 37 absolute and relative phospholipid levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 14 phospholipid levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 7 phospholipid levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from − 1.83 to 7.14%.

The impact of BMI on total lipid levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 11 out of the 18 absolute and relative total lipid levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 6 total lipid levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 2 total lipid levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from 2.30 to 2.47%.

The impact of BMI on fatty acid levels and cholelithiasis risk

As presented in Table 2, we identified a significant association between BMI and 12 out of the 18 absolute and relative fatty acid levels included in our study. As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 4 fatty acid levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that 4 fatty acid levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of risk ranging from 2.19 to 6.57%.

The impact of BMI on other metabolites and cholelithiasis risk

The study also included 14 additional metabolites, consisting of three apolipoproteins, four metabolites related to glycolysis, glycoprotein acetyls, two ketone bodies, acetate, acetone, albumin, and creatinine. As shown in Table 2, we found that BMI was associated with acetoacetate levels (β = 0.0926, p = 0.000486), albumin levels (β=-0.107, p = 0.000134), apolipoprotein A1 levels (β=-0.161, p < 0.0001), the ratio of apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1 levels (β = 0.0807, p = 0.0121), glucose levels (β = 0.0940, p = 0.000153), glycoprotein acetyls levels (β = 0.166, p < 0.0001), and 3-hydroxybutyrate levels (β = 0.0648, p = 0.0300). As demonstrated in Table 3, our study found that 2 other metabolite levels are associated with cholelithiasis from the FinnGen cohort. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, further analysis indicated that the ratio of apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1 levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis risk, with the mediated proportion of -2.38%.

Discussion

This study highlights the significant association between BMI and various metabolic biomarkers, providing insight into how BMI influences metabolic processes and the risk of cholelithiasis. The analysis identified 176 metabolites associated with BMI, of which 49 were found to mediate the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis, indicating the complex pathways through which BMI impacts disease risk.

Our findings reveal a significant association between BMI and several key metabolic traits, including amino acids, cholesterol, and lipoproteins. For instance, both our study and previous research20 have demonstrated that BMI is associated with increased levels of branched-chain amino acids. These amino acids have previously been linked to metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance21,22, cardiovascular diseases23,24, and type 2 diabetes20, suggesting that higher BMI may exacerbate metabolic dysfunction through amino acid metabolism. However, despite the significant changes in amino acid levels, our analysis did not find evidence that these shifts contribute directly to cholelithiasis risk. Cholesterol metabolism also emerged as a critical pathway influenced by BMI. We observed significant associations between BMI and both cholesteryl ester and free cholesterol levels. A previous study10 revealed a negative correlation between BMI and serum HDL cholesterol levels, while another study showed an inverse relationship between HDL cholesterol and the risk of cholelithiasis25. This seems to suggest a potential pathway through which BMI may influence the risk of cholelithiasis, and our results also support this conclusion. Notably, several cholesterol esters and free cholesterol levels mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis, with mediation proportions ranging from 2 to 5%. This suggests that BMI-related alterations in cholesterol metabolism could play a role in the development of cholelithiasis, particularly through increased cholesterol saturation in bile. Additionally, BMI was found to influence several other metabolic markers, including acetoacetate, glucose, and glycoprotein acetyls. These markers are indicative of broader metabolic changes associated with obesity, such as impaired glucose metabolism and inflammation. Notably, the ratio of apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1, an important marker of cardiovascular risk26, was also affected by BMI and mediated the relationship between BMI and cholelithiasis, although the mediated effect was negative (-2.38%). We found that as BMI increases, this ratio also increases. However, we found that this higher ratio is inversely associated with the risk of cholelithiasis. The negative mediation effects observed for the ratio of apolipoprotein B to apolipoprotein A1, phospholipid levels in VLDL, and triglyceride levels in large LDL and IDL suggest a complex interplay between lipid metabolism, BMI, and cholelithiasis risk. While BMI is generally associated with increased risk of cholelithiasis through lipid dysregulation, these reverse mediation effects imply that certain lipid profile changes may counteract or modulate this risk. For example, alterations in the distribution of apolipoproteins or triglycerides may influence cholesterol saturation in bile, potentially reducing the risk of gallstone formation despite the overall increase in BMI. These findings highlight the nuanced role of lipid metabolism in the BMI-cholelithiasis relationship and suggest that not all lipid changes driven by BMI necessarily exacerbate gallstone risk.

Our study reveals that BMI influences the risk of cholelithiasis through multiple metabolic pathways, particularly in lipid metabolism. First, BMI is significantly associated with various cholesterol-related metabolites, such as cholesterol esters and free cholesterol. These changes may promote gallstone formation by influencing the saturation of cholesterol in bile. Other metabolites, such as fatty acids and phospholipids, also participate in this process. The levels of these metabolites change with increasing BMI and may affect the risk of cholelithiasis by altering lipid accumulation in the liver and gallbladder. Furthermore, although amino acid metabolism changes are closely linked to BMI, our analysis did not find direct evidence that amino acid level changes contribute to gallstone risk. Overall, the metabolic changes triggered by BMI affect the occurrence of gallstones through various pathways, such as lipid metabolism, suggesting that controlling BMI may help reduce metabolic dysfunctions and, thereby, lower the risk of cholelithiasis.

This study inevitably has certain limitations. First, the findings cannot be generalized to populations outside of Europe, as the data used primarily came from European populations. Second, due to data limitations, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses based on age and gender. Third, also due to data constraints, while the study provides qualitative insights, it cannot conclusively demonstrate whether certain metabolic levels increase and then decrease as BMI rises.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the role of BMI in altering key metabolic pathways, including cholesterol, triglyceride, phospholipid, and fatty acid metabolism, which contribute to gallstone formation. We identified metabolites such as cholesteryl esters, free cholesterol, triglycerides, and phospholipids, which mediate the BMI-cholelithiasis relationship. These findings reinforce the critical role of BMI in shaping metabolic profiles, suggesting that controlling BMI may help mitigate disruptions in metabolic processes and reduce disease risk. Future research should focus on further understanding these mechanisms and exploring potential therapeutic targets.

Data availability

All GWAS data used in this study are available in the IEU open GWAS project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/) and the FinnGen Biobank (https://r10.risteys.finngen.fi/).

References

World-Health-Organization & Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed September 19 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. Obesity and risk for respiratory diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1197730 (2023).

Elagizi, A. et al. An overview and update on obesity and the obesity paradox in cardiovascular diseases. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 61(2), 142–150 (2018).

Larsson, S. C. & Burgess, S. Causal role of high body mass index in multiple chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. BMC Med. 19, 1–10 (2021).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: an observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 10(4), 253–263 (2022).

Khandekar, M. J., Cohen, P. & Spiegelman, B. M. Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 11(12), 886–895 (2011).

Saltiel, A. R. & Olefsky, J. M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Investig. 127(1), 1–4 (2017).

Adams, S. H. Emerging perspectives on essential amino acid metabolism in obesity and the insulin-resistant state. Adv. Nutr. 2(6), 445–456 (2011).

McCormack, S. E. et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 8(1), 52–61 (2013).

Wakabayashi, I. Relationships of body mass index with blood pressure and serum cholesterol concentrations at different ages. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 16, 461–466 (2004).

Kharga, B. et al. Obesity not necessary, risk of symptomatic cholelithiasis increases as a function of BMI. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR. 10(10), PC28 (2016).

Larsson, S. C., Butterworth, A. S. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization for cardiovascular diseases: principles and applications. Eur. Heart J. 44(47), 4913–4924 (2023).

Richardson, T. G. et al. Characterising metabolomic signatures of lipid-modifying therapies through drug target mendelian randomisation. PLoS Biol. 20(2), e3001547 (2022).

The OpenGWAS Project. https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/. Accessed September 18 (2024).

The FinnGen Biobank. https://r10.risteys.finngen.fi/. Accessed September 18 (2024).

Davey Smith, G. & Hemani, G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23(R1), R89–R98 (2014).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey Smith, G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46(6), 1985–1998 (2017).

Glickman, M. E., Rao, S. R. & Schultz, M. R. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67(8), 850–857 (2014).

Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. elife 7, e34408 (2018).

Lynch, C. J. & Adams, S. H. Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10(12), 723–736 (2014).

Lackey, D. E. et al. Regulation of adipose branched-chain amino acid catabolism enzyme expression and cross-adipose amino acid flux in human obesity. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 304(11), E1175–E1187 (2013).

Zhao, X. et al. The relationship between branched-chain amino acid related metabolomic signature and insulin resistance: a systematic review. J. Diabetes Res. 2016(1), 2794591 (2016).

Hu, S. et al. Causal relationships of circulating amino acids with cardiovascular disease: a trans-ancestry Mendelian randomization analysis. J. translational Med. 21(1), 699 (2023).

Li, Z., Wang, Y. & Sun, H. The role of branched-chain amino acids and their metabolism in cardiovascular diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 17(1), 85–90 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Blood lipid metabolism and the risk of gallstone disease: a multi-center study and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 21(1), 26 (2022).

Walldius, G. & Jungner, I. The apoB/apoA-I ratio: a strong, new risk factor for cardiovascular disease and a target for lipid‐lowering therapy–a review of the evidence. J. Intern. Med. 259(5), 493–519 (2006).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the UK Biobank, the FinnGen Biobank, and the IEU open GWAS project developed by The MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) at the University of Bristol.

Funding

This research was supported by the 2023 Annual Health research project of Anhui Health Commission AHWJ2023A10015, under the direction of Dr. Zhao Feng. It was also funded by the 2023 Annual Medical Special Cultivation Project (Major Project H2) of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Grant Number: YZ2023H2A006), the Graduate Innovation Fund Project of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Graduate Document [2022] No. 17).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was designed by Feng Zhao and Wenwen Yang. Statistical analyses were performed by Yanjiang Yang and Wenwen Yang. The manuscript was written by Feng Zhao, Wenwen Yang, and Yanjiang Yang. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, F., Yang, Y. & Yang, W. Exploring the causal impact of body mass index on metabolic biomarkers and cholelithiasis risk: a Mendelian randomization analysis. Sci Rep 15, 415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83217-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83217-6