Abstract

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are among the most widely used drugs worldwide. However, their influence on the progression of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in established chronic kidney disease (CKD) cases is unclear. Using the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment database encoded by the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership–Common Data Model (OMOP-CDM), patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD initiating PPIs or histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) for over 90 days were enrolled from 2012 through 2021. Incidence of ESKD events between the groups were compared using a cox proportional hazard model. A total of 34,656 eligible patients were included. Of the patients, 65.1% had CKD stage 3, 44.5% aged > 75 years, 59.8% were male individuals, and 68.3% had diabetes. After 1:1 propensity score matching, ESKD progression was observed in 2327 out of 19,438 patients and it was more frequent in PPI users (incidence rate, 10.5/100PYs) than that in H2RA users (incidence rate, 9.2/100PYs; IRR, 1.14 [1.07–1.12]). Using the subgroup analysis, IRR was significantly higher in patients with CKD stage 3 (IRR 1.40 [1.21–1.60]), whereas it was not in those with CKD stage 4 (IRR 1.04 [0.94–1.15]). A similar trend was observed in patients with CKD 3 or 4 with and without diabetes. In general, PPI use is associated with a 14% higher risk of ESKD progression in patients with CKD stage 3 or 4. However, the influence of PPIs differed according to the comorbidities and risks of adverse kidney outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are acid suppressive agents that include omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, and dexlansoprazole1. Due to their efficacy in controlling acid-related gastrointestinal disease2 and relatively safe pharmacological class label, they are one of the most widely used drugs in the world. In 2022, omeprazole was the 2nd most dispensed item in England3. In the USA, omeprazole was the ninth most commonly prescribed medicine in 2021, with more than 54 million prescriptions4. In South Korea, omeprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole were the most commonly prescribed drugs between 2016 and 2020, with the utilization rate of PPIs of 25.1 daily drug dose per 1000 person-days5.

With increasing utilization, several adverse events have been reported6. Regarding kidney disease, acute interstitial nephritis and acute kidney injury have been noted7. Furthermore, multiple real-world observational studies have suggested an increased risk of incident chronic kidney disease (CKD) in long-term PPI users8,9,10,11,12.

End-stage kidney (ESKD) disease is the 10th most common cause of death globally13. Since the incidence of dialysis requiring ESKD is increasing worldwide and South Korea is the 4th highest country in the increasing rate, identifying and controlling modifiable risk factors for ESKD progression in patients with CKD are urgently required in Korea14.

In a report by Lee et al., PPIs were more commonly used in patients with CKD patients than in non- CKD patients in Korea15. However, whether control of long-term use of PPIs can reduce the incidence of ESKD progression in CKD patients is unknown, as previous retrospective studies demonstrated opposing results on adverse kidney outcomes in patients with established CKD16,17,18. We hypothesized that long-term use of PPIs may increase the risk of ESKD progression in patients with CKD. The incidence of ESKD progression was evaluated using a Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA), the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership—Common Data Model (OMOP-CDM) in South Korea.

Methods

Data source

We used the HIRA database between January 2012 and December 2021, encoded in OMOP-CDM version 5.3.1. The HIRA database is a national claims database generated by the Korean health insurance system that includes the medical information of nearly the entire population from multiple hospitals in South Korea19. HIRA data consisted of five tables: demographics, in-hospital treatment details, disease details, out-of-hospital prescription details, and nursing institute information20. We used HIRA data, converted it into the OMOP-CDM, and adapted it for the ATLAS analytical tool.

Study design and population

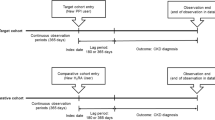

This retrospective study was based on the national claims database in South Korea. Patients aged > 18 years with established stage 3 or 4 CKD were included. We did not include patients who underwent hemodialysis or kidney transplantation 90 days before cohort entry. The target cohort was defined as stage 3 or 4 CKD with newly started PPIs (eTables 1 and 2) for > 90 days. The comparative cohort had the same characteristics as the target cohort, except for histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) use. We excluded patients who were prescribed either H2RA or PPI within 90 days before cohort entry. The index date was the first day of starting long term prescription of PPIs or H2RAs. We followed up the patients for up to three years until ESKD progression (Fig. 1). Follow-up was censored if cross-medication or any cause of death before ESKD was detected during the observation period. Regarding the subgroup analysis, we created separate CKD stage 3 or 4 cohorts and diabetic or non-diabetic cohorts among the patients with CKD stage 3 or 4, using the same conditions described above. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome was ESKD incidence. We defined it as the commencement of renal replacement therapy, including hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation (eTable 2). We assumed that ESKD observed 30 days after cohort entry as drug-associated.

Covariates

Baseline covariates included age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), liver cirrhosis (LC), and concurrent medications such as renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and statins. Concurrent medications and comorbidities were detected using the OMOP-CDM concept ID and code version 5.3.1 (eTables 1 and 2). Information on comorbidity covariates was retrieved based on data collected within 12 months before cohort entry. Moreover, information on concurrent medication covariates was retrieved based on data collected within 3 months before cohort entry.

Statistical analyses

The incidence rate of ESKD per 100 person-years (PYs) in each group was determined along with the incidence rate ratio (IRR) between the target and comparator cohorts. After calculating the crude IRR, 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using L1-regularized large-scale logistic regression models with adjustments for covariates, including age, sex, comorbidities, and concurrent medications within 90 days prior to the index date. PSM was performed in the OHDSI CohortMethod package21, which enabled efficient and accurate propensity score estimation for balancing covariates in high-dimensional observational data. A default caliper of 0.2 was applied to ensure close matching on propensity scores. To assess covariate balance after PSM, we set a threshold for the adjusted standardized mean difference to be less than 0.1 for all covariates. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to estimate outcome risk. All statistical tests were two-sided; statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using OHDSI’s ATLAS (version 2.7.6) and the R statistical software (version 3.5.1). Analyses were performed within the secure, closed, environment of the HIRA nationwide database. The environment restricted external access, ensuring data integrity and privacy.

Results

Study population

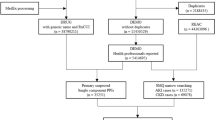

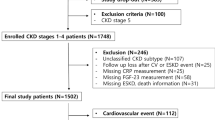

Between January 2012 and December 2021, 41,092 patients met the study criteria, with 22,973 and 18,119 in the PPI and H2RA groups, respectively. Excluding 2307 patients with crossed-drug medications before cohort entry and 1822 patients who reached the outcome within 30 days of observation, we found 19,394 PPI and 15,262 H2RA users. After 1:1 PSM, 9719 patients’ data were assembled for each group (Fig. 2). The distribution of the standardized difference in the means of the covariates before and after adjustment for the propensity score is plotted in eFigure 1.

Baseline characteristics

Among the 34,656 patients with CKD 3 or 4, 15,419 (44.5%) aged > 75 years, 20,741 (59.8%) were male participants, 22,560 (65.1%) had CKD stage 3, and 12,096 (34.9%) had CKD stage 4. Overall, 23,679 (68.3%) patients had diabetes, 31,724 (91.5%) had hypertension, 9422 (27.2%) had CHF, and 1168 (3.4%) had LC, all of which occurred more frequently in PPI users than in H2RA users. The prescription rates of the concurrent medications showed a similar trend (Table 1).

Progression to ESKD among patients with CKD3 or 4

Among the 19,394 PPI users, patients were followed up for 20,892 PYs; ESKD was observed in 2134 patients (IR, 10.21 (9.78–10.65)/100 PYs), while 1916 H2RA users progressed to ESKD during 20,925 PYs (IR 9.16 (8.75–9.57)/100 PYs). The IRR was significantly higher among PPI users (IRR, 1.12 (1.05–1.19)). After 1:1 PSM, the IR for ESKD progression was still significantly higher in PPI users [IR 10.52 (9.90–11.14)] compared with H2RA [IR 9.19 (8.67–9.71)], corresponding to an IRR of 1.15 (1.06–1.24)] (Table 2). The Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed the same results (Fig. 3).

Differences in the role of PPIs according to the specific comorbidities

CKD stage 3 vs. 4

Overall, nearly 30% of the patients had CKD stage 4; progression to EKSD was more frequently observed in patients with CKD stage 4 than in those with stage 3 CKD. In the subgroup of patients with CKD stage 4, the incidence rate of EKSD progression was 19.80 (18.34–21.25)/100 PYs in the PPI groups and 18.97 (17.70–20.25)/100 PYs in those receiving H2RAs, without difference in IRR [1.04 (0.95–1.15)]. In patients with CKD stage 3, the incidence rate of ESKD in PPIs and H2RAs were 5.75 (5.18–6.31)/100 PYs and 4.13 (3.71–4.56)/100 PYs, respectively. Contrary to the cases in the CKD 4 subgroup, the ESKD progression rate was significantly higher in PPI users than in those administered H2RAs [IRR, 1.39 (1.21–1.60)] (eTable 3).

Diabetes vs. no diabetes

In the CKD 3 or 4 group, approximately 70% had diabetes. In patients with CKD with diabetes, the IR of ESKD in PPIs and H2RAs cases were 11.74 (10.95–12.54)/100 PYs and 10.81 (10.13–11.50)/100 PYs, respectively, without differences in IRR [1.09 (0.99–1.19)]. However, in patients without diabetes, it was 7.95 (7.00–8.90)/100 PYs and 5.86 (5.14–6.59)/100 PYs, which was more frequent in the PPI groups than in those receiving H2RAs [IRR, 1.36 (1.14–1.61)] (eTable 4).

Differences in nephrotoxic effects of PPIs by baseline comorbidities

We stratified the patients according to baseline comorbidities and calculated the incidence rate in a separate propensity score-matched model for each disease. We assumed the incidence rate in the comparator group as the baseline risk for ESKD progression, which was the highest in CKD stage G4 (18.97 (17.70–20.25)/100 PYs), followed by CKD 3 or 4 with CHF (10.84 (9.65–12.03)/100 PYs), and CKD 3or 4 with diabetes (10.81(10.13–11.49)/100 PYs). Baseline risks for ESKD progression were relatively lower in patients with CKD 3 or 4 without specific comorbidities and in those with CKD stage 3 (4.13 (3.71–4.56)/100 PYs). Differences in IRR between PPIs and H2RAs were significant in the subgroups with a relatively lower risk of ESKD progression. In contrast, the rate of ESKD progression was not different between PPIs and H2RAs users in the subgroups with a higher incidence rate of ESKD progression (Fig. 4).

Differences in nephrotoxic effects of PPIs by the incidence rate of ESKD of comparator cohort. The number in each bar represents incidence rate of ESKD per 100 person years. Dotted lines represent overall incidence rate in proton pump inhibitor (PPI, orange line) and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RA, green line) users. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. ESKD end-stage kidney disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, PPI proton pump inhibitor, H2RA histamine-2 receptor antagonist, CHF chronic heart failure, DM diabetes, HTN hypertension, LC liver cirrhosis, IR incidence rate.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the influence of PPIs on ESKD progression in patients with established CKD using HIRA-OMOP CDM in South Korea. In patients with CKD stage 3 or 4 with long-term (at least 90 days) PPI use, the incidence of ESKD progression was 12% higher than that in those using H2RA. Furthermore, the incidence rate ratio was even higher after robust control of multiple covariates, such as diabetes, hypertension, CHF, and concurrent medications. Among patients with CKD, the effect of PPIs differed according to individual risks. In the groups with a low risk of ESKD progression, such as patients with CKD stage 3 and CKD without hypertension or diabetes, long-term use of PPIs was an attributable risk factor for ESKD. In contrast, in the group that already had multiple risks for ESKD progression, CKD stage 4 or CKD with diabetes, PPI utilization added no further risk of ESKD progression compared with those receiving H2RA.

Multiple observational studies have shown that in patients with previously normal kidney function, long-term use of PPIs is associated with an increased risk of developing incident CKD8,9,10,11,12. However, in patients with established CKD, the role of PPIs in adverse kidney outcomes is unclear; two previous studies showed different results. Grant et al.16 retrospectively retrieved electronic health records (EHR), then assembled patients with 3824 CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) lower than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, with 1195 in the PPI groups and 2629 in non-PPI groups. At baseline, the PPI group was younger; had a lower eGFR; and had a greater prevalence of proteinuria, myocardial infarction, and diabetes. During a median follow-up period of 5.6 years, the incidence of major adverse renal events (MARE) was 55% in PPI users and 36.6% in non-PPI users. Using the multivariate analysis, the risk of MARE was 13% higher in the PPI group than in the non-PPI group. In the prospective study by Liabeuf et al. evaluating the incidence of ESKD in patients with CKD stage 2–5 for a median follow-up of 3.9 years, the adjusted hazard ratios associated with PPI prescription were higher at 1.74 fold for ESKD18. Cholin et al.17 also assembled EHR-derived CKD cohorts, defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for over 90 days. In 25,455 patients with CKD, 8646 were active PPI users, 848 were active H2RA users, and the remaining 15,961 did not take any medication. During a median follow-up period of 4.1 years, the cumulative incidence of ESKD with death as a competing risk in patients with PPIs, H2RAs, and none was 2.0 (1.7–2.4)%, 1.5 (0.8–2.8)%, and 1.6 (1.4–1.9)%, respectively, which was not different between the groups in both the unadjusted and adjusted models. The authors suggested that the different results between the studies were possibly associated with the differences in the baseline characteristics in Grant et al.’s study. The PPI groups had higher risk factors for ESKD progression than did non-PPI users.

Our nationwide study included a large number of patients with CKD stage 3 or 4 with multiple comorbidities in each group. In the crude model, diabetes, hypertension, CHF, and LC were more frequent in PPI users. However, we adjusted for these differences using 1:1 PSM. The IRR of ESKD progression in both crude and PSM models was significantly higher in the PPI group. To eliminate the confounding effect of baseline comorbidities on EKSD progression, we stratified the patients according to the specific underlying disease and assembled separate propensity score matched analyses. When we arranged the subgroups based on the incidence rate of comparators, stage 3 or 4 CKD without HT had the lowest incidence, followed by those with stage 3 CKD, stage 3 or 4 CKD without diabetes, CHF, and LC. CKD stage 4 and stage 3 or 4 CKD with diabetes had the highest incidence rates of ESKD progression. The use of PPIs was attributed to ESKD progression in the low-risk group, whereas the utilization of PPIs did not add additional risks in the higher-risk groups. Based on our findings, we speculate that the risk of PPIs for ESKD progression in patients with CKD differs according to the given risks and that the prescription of long-term PPIs needs to be individualized. In patients with lower risk factors for ESKD progression, such as early-stage CKD or CKD without comorbidities, long-term use of PPIs could have more harm than benefits; meanwhile, in patients with advanced-stage CKD with diabetes, the indicated prescription of PPIs may have more benefits than harm.

However, the mechanisms underlying the progression of ESKD in patients with CKD are unclear. Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) with or without acute kidney injury has been suggested as a possible mechanism for PPI nephrotoxicity22,23. However, evidence of biopsy-proven AIN followed by PPI prescription is still sparse; therefore, further studies are required to reveal the causative relationship between PPIs and ESKD progression in patients with CKD.

This nationwide claims data-based study has several strengths. First, the study population was relatively large. Even after 1:1 PSM, data of 9719 patient were available. Second, the confounding effect of cross-medication between the two cohorts was controlled. As national claims data were used, the system easily detected cross-medication from multiple hospitals. For example, if one person was prescribed PPIs from Hospital A and H2RAs from Hospital B during the study period, this system integrally detected this cross-medication, and we censored the follow-up.

This study has some limitations. First, laboratory data such as proteinuria or eGFR values were not available. The HIRA OMOP-CDM database currently does not have laboratory data. Therefore, we detected CKD and its stage based on diagnostic codes imputed by physicians. Since non-nephrology-based physicians may not code early-stage CKD, some patients with stage 3 CKD may have been excluded from the study. Second, although all included patients were exposed to PPIs for at least 90 days, total exposure duration might have differed by specific subgroups. Therefore, differences in the PPI exposure time might have affected the results in diverse subgroup analyses, which we did not consider. Third, in the estimation of incidence rate, we used a cause-specific hazard model to address the competing risk of death, treating death as a censoring event in our analyses. As HIRA dataset lacked information on the cause of death, we could not distinguish between ESKD-related and other causes of death. This limitation may have affected the calculation of the incidence rate ratio by shortening the observation period and reducing the number of patients at risk. Fourth, only a small proportion of the patients were prescribed SGLT2 inhibitors since these data were extracted from 2012 to 2021 when the protective role of SGLT2 inhibitors in ESKD progression24,25 has not yet been determined. Therefore, this study could not evaluate the combined effects of PPI and SGLT2 inhibitors.

In conclusion, we observed an increased risk of ESKD progression in PPI users in an population with established CKD. However, the risk was diverse based on the individual risk of adverse kidney outcomes; therefore, personalized prescriptions balancing risk and harm should be considered.

Data availability

We used Korean national claim data (Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA), the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership—Common Data Model (OMOP-CDM)) after permission, hence the availability of raw data is owned by “HIRA” in South Korea. The analytical R code is available from author KJ (jinmi@pusan.ac.kr).

References

Shanika, L. G. T., Reynolds, A., Pattison, S. & Braund, R. Proton pump inhibitor use: Systematic review of global trends and practices. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 79, 1159–1172 (2023).

NICE Guideline cg184. 2019 Surveillance of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease and Dyspepsia in Adults: Investigation and Management (2019).

Statista. Leading chemical substances dispensed in England in 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/378445/prescription-cost-analysis-top-twenty-chemicals-by-items-in-england/.

ClinCalc, L. L. C. Drug usage statistics, United States (2013–2021). https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Omeprazole.

Oh, J.-A., Lee, G.-M., Chung, S.-Y., Cho, Y.-S. & Lee, H.-J. Utilization trends of proton pump inhibitors in South Korea: Analysis using 2016–2020 Healthcare Bigdata Hub by Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Yakhak Hoeji 65, 276–283 (2021).

Koyyada, A. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for various adverse manifestations. Therapie 76, 13–21 (2021).

Al-Aly, Z., Maddukuri, G. & Xie, Y. Proton pump inhibitors and the kidney: Implications of current evidence for clinical practice and when and how to deprescribe. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 75, 497–507 (2020).

Lazarus, B. et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 238–246 (2016).

Arora, P. et al. Proton pump inhibitors are associated with increased risk of development of chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 17, 112 (2016).

Xie, Y. et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 3153–3163 (2016).

Peng, Y. C. et al. Association between the use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of ESRD in renal diseases: A population-based, case-control study. Med. (Baltim). 95, e3363 (2016).

Klatte, D. C. F. et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of progression of chronic kidney disease. Gastroenterology 153, 702–710 (2017).

World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death.

Kim, D. H. et al. Kidney Health Plan 2033 in Korea: Bridging the gap between the present and the future. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 43, 8–19 (2024).

Lee, H. J. et al. Correction: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients are exposed to more proton pump inhibitor (PPI)s compared to non-CKD patients. PLOS One 13, e0207561 (2018).

Grant, C. H. et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and progression to major adverse renal events: A competing risk analysis. Q. J. M. 112, 835–840 (2019).

Cholin, L. et al. Proton-pump inhibitor vs. H2-receptor blocker use and overall risk of CKD progression. BMC Nephrol. 22, 264 (2021).

Liabeuf, S. et al. Adverse outcomes of proton pump inhibitors in patients with chronic kidney disease: The CKD-REIN cohort study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 87, 2967–2976 (2021).

Kim, J. W. et al. Scalable infrastructure supporting reproducible nationwide healthcare data analysis toward FAIR stewardship. Sci. Data 10, 674 (2023).

Kyoung, D. S. & Kim, H. S. Understanding and utilizing claim data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) and Health Insurance Review & Assessment (HIRA) database for research. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 11, 103–110 (2022).

Schuemie, M. et al. Health-analytics data to evidence suite (HADES): Open-source software for observational research. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 310, 966–970 (2024).

Muriithi, A. K. et al. Biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis, 1993–2011: A case series. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 64, 558–566 (2014).

Antoniou, T. et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open 3, E166–E171 (2015).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1436–1446 (2020).

The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group et al. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 117–127 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Biomedical Research Institute Grant (202400620001), Pusan National University Hospital.

Funding

This study was supported by Biomedical Research Institute Grant (202400620001), Pusan National University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.H. conceptualized the study, obtained funding, and wrote the manuscript. Y.J.L. designed the study, and N.K.J. supervised the study. Y.D.H. implemented the analyses, and J.K. performed the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval to perform the analyses was obtained with a waiver of informed consent from the Pusan National University IRB Committee [PNUH IRB 2308-021-130].

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y.J., Kim, J., Yu, D.H. et al. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors was associated with rapid progression to end stage kidney disease in a Korean nationwide study. Sci Rep 14, 31477 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83321-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83321-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

PPI use increases risk of ESKD in patients with renal failure

Reactions Weekly (2025)