Abstract

Insecticide resistance escalation is decreasing the efficacy of vector control tools. Monitoring vector resistance is paramount in order to understand its evolution and devise effective counter-solutions. In this study, we monitored insecticide resistance patterns, vector population bionomics and genetic variants associated with resistance over 3 years from 2021 to 2023 in Uganda. Anopheles funestus s.s was the predominant species in Mayuge but with evidence of hybridization with other species of the An. funestus group. Sporozoite infection rates were relatively very high with a peak of 20.41% in March 2022. Intense pyrethroid resistance was seen against pyrethroids up to 10-times the diagnostic concentration but partial recovery of susceptibility in PBO synergistic assays. Among bednets, only PBO-based nets (PermaNet 3.0 Top and Olyset Plus) and chlorfenapyr-based net (Interceptor G2) had high mortality rates. Mosquitoes were fully susceptible to chlorfenapyr and organophosphates, moderately resistant to clothianidin and resistant to carbamates. The allele frequency of key P450, CYP9K1, resistance marker was constantly very high but that for CYP6P9A/b were very low. Interestingly, we report the first detection of resistance alleles for Ace1 gene (RS = ~ 13%) and Rdl gene (RS = ~ 21%, RR = ~ 4%) in Uganda. The qRT-PCR revealed that Cytochrome P450s CYP9K1, CYP6P9A, CYP6P9b, CYP6P5 and CYP6M7 were consistently upregulated while a glutathione-S-transferase gene (GSTE2) showed low expression. Our study shows the complexity of insecticide resistance patterns and underlying mechanisms, hence constant and consistent spatial and temporal monitoring is crucial to rapidly detect changing resistance profiles which is key in informing deployment of counter interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria remains the largest contributor to mortality and morbidity especially in African pregnant women and children. In 2022, there were an estimated 249 million cases globally with an estimated 608,000 deaths with the majority occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa mainly due to P. falciparum parasite1. Uganda underwent a malaria resurgence2 and was among the four countries that contributed to almost 50% of the global cases1. Despite the deployment of various tools such as; Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs), Indoor residual Spraying (IRS) and larvicides, progress has stalled. Vector control is currently the pillar of malaria control targeting mainly Anopheles funestus and Anopheles gambiae species and solely rely on the use of insecticides3. Pyrethroids were the only class of insecticides used in bednets—the primary malaria control tool in Africa1. As a result, pyrethroid resistance became widespread in major malaria vectors and currently, there is now resistance to all classes of insecticides including the newly introduced ones4,5,6. The scale-up of vector control interventions especially bednets could have contributed to the spread of resistance due to the selection pressure on an evolutionary scale. By 2020, bednet use in Africa in some countries like Uganda reached the 80% mark needed for universal coverage, with others following a similar trend7. The efficacy of bednets especially single active ingredient (AI) decreased over the years due to pyrethroid resistance8 as seen in Uganda9,10, Malawi11 and Cameroon12. To manage insecticide resistance, formerly, piperonyl butoxide (PBO) was incorporated into LLINs to increase the potency of pyrethroids hence increasing the killing effect13. Indeed, PBO nets produced a significantly better performance than pyrethroid-only bednets for example in Tanzania14 and Uganda15,16 but the effectiveness has also decreased in recent years17,18,19. A key factor decreasing the efficacy of PBO nets is the rise of resistance escalation as reported in Uganda20, Malawi11 and Ghana21 even further leading to cross-resistance with other classes of insecticides such as carbamates22. These scenarios underscore the importance of probably avoiding continuous deployment of the same classes of insecticides in areas with escalated resistance levels or cross-resistance. Hence, the recent strategy has been the introduction of two new classes of insecticides; Pyrroles for bednets and Neonicotinoids for IRS23 and these are currently showing very promising results due to different modes of action. Clothianidin is a neonicotinoid that acts by targeting the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) in the insect central nervous system24. Chlorfenapyr is a pyrrole which acts by disrupting energy production using toxins produced by oxidases in insect cells25,26.

In An. funestus, insecticide resistance is principally driven by the overexpression of metabolic genes, mainly cytochrome P450s (CYPs)27,28,29 such as; CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b30 and CYP9K1 which was discovered to be overexpressed in Uganda and Cameroon31,32. The expression of these key metabolic genes significantly differs geographically in Anopheles vectors33. These variations indicate a possible existence of distinct selection pressures and de-novo evolutionary processes with limited gene flow over long distances possibly due to geographical barriers or just insufficient time for resistance alleles to spread between regions of Africa. Furthermore, non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) alleles have been detected in CYP6P9A34, CYP6P9b35 and CYP9K136 and also two structural variants (SVs); the 6.5-Kb SV found between CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b genes37 and 4.3-Kb SV which is found between CYP6P9b and CYP6P5 genes38. The genetic haplotype of the 6.5-Kb SV is closely linked with CYP6P9a/b markers and for 4.3-Kb SV with CYP9K1 marker hence having the same allele frequency pattern as the metabolic markers and together, they drastically reduce the performance of bednets38.

Monitoring Insecticide resistance in principal malaria vectors is a key pillar of the Global Plan for insecticide resistance management39. This undertaking usually assists in uncovering any changes and signals of selection, resistance escalation and spread, which is critical in informing timely and counter-effective solutions. Both insecticide susceptibility tests and use of resistance markers are applied in monitoring resistance39,40. This has helped uncover key information on the evolution of resistance geographically like the distribution of resistance markers such as; CYP6P9a and CYP6P9b being fixed in southern Africa34,35 and southern Tanzania41, but at very low allele frequencies in Uganda9. In contrast, the CYP9K1 marker (G454A) being fixed in Uganda and parts of Cameroon but very low frequencies in southern Africa9,36. Furthermore, other known resistance markers discovered in An. funestus include; a SNP found within glutathione-s-transferase epsilon 2 (GSTE2) gene, GSTe2-119F metabolic marker discovered in West Africa at high frequency42 but still at very low frequency in East Africa9,41 and two target-site markers; in the acetylcholinesterase (Ace1) gene, N458I-Ace1 discovered in Malawi which confer resistance to organophosphates and carbamates43 and in the dieldrin resistance gene (Rdl), A296S-Rdl discovered in Burkina-Faso and Cameroon conferring resistance to dieldrin and DDT44. Except for A296S which was detected in 200944 but subsequently reduced in frequency to zero by 20209, mutant alleles for both target site markers have never been detected in East Africa. The only known target-site marker is the Vgsc-L976F variant which is for a knockdown resistance (kdr), was detected very recently in East Africa and confers resistance to DDT but is currently localised in Tanzania45.

Insecticide resistance is very dynamic in space and time. Mosquito populations often change depending on selection pressure which eventually could alter resistance mechanisms and population structure as seen with the rise in An. funestus populations due to LLIN use46. In 2020, pyrethroid resistance escalation was detected in Uganda but the markers did not associate with the resistance phenotype despite the overexpression of some key genes9. We carried out a 3-year temporal study from 2021 to; (1) assess if these patterns were consistent, (2) elucidate the genetic variants that could be driving pyrethroid resistance in Uganda and (3) document temporal changes in vector bionomics. This information is crucial for in-country malaria control efforts, especially at a time when a variety of interventions are being rolled out and their impact needs to be accurately assessed.

Methods

Ethical statement

The protocol to conduct this study including Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) was approved by The Uganda Virus Research Institute Research Ethics Committee (UVRI REC) (Ref: GC/127/833) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) (HS2063ES). Before mosquito collections, written, informed and signed consents were obtained from the heads of the households. All information regarding the study was included in the consent form and participants were taken through the consent forms where needed. Additionally, the information in the consent form was translated into the local language where needed.

Study site and mosquito collections

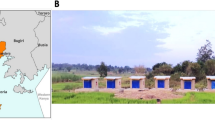

The study was conducted in Mayuge district in eastern Uganda (00° 24ʹ 20.06ʺ N 033° 47ʹ 57.50ʺ E) (Fig. 1) from 2021 to 2023 targeting four villages; Kigandalo, Buyaga, Bubalya (Kigulu) and Lwandera (Bukabooli) (Fig. 1). Mayuge is not an IRS district i.e. household spray operations are not conducted in the district as part of the national malaria control program (NMCP) yearly activities, but, it immediately borders Bugiri and is close to Tororo which are all IRS districts. History of IRS include usage of bendiocarb and Actellic interchangeably up to 2018, then Fludora Fusion and Sumishield from 2019-2022 and back to Actellic in 2023 and 2024 with few houses receiving Sumishield in 20232. Vector control interventions in Mayuge have mainly been through the distribution of ITNs since 201247. In our study, mosquitoes were collected in October 2021, March 2022, November 2022, May 2023 and November 2023 from 50 households selected at random. The electric prokopack aspiration technique (John W. Hock co., USA) was used since the aim was to collect alive blood-fed indoor resting female mosquitoes. Mosquito collection was done for five days in the early morning between 4.30 and 9 a.m. Aspirated mosquitoes were kept in cages and then morphologically identified using keys by Coetzee48 and separated into Anopheles gambiae s.l from An. funestus s.l, other Culicines and male categories. The sorted Anopheles mosquitoes were then transferred to paper cups (separating An. funestus from An. gambiae), given a 10% sugar solution and kept for 3–5 days until gravid. To obtain eggs from the gravid females, the forced egg-laying technique was used49. Harvested eggs were shipped to the Centre for Research in Infectious Diseases (CRID, Cameroon) for the rearing of progeny. Carcasses of the field mosquitoes (F0) were separated into oviposited and non-oviposited and stored in silica gel in Eppendorf tubes for DNA extraction.

Mosquito rearing

All mosquitoes were reared under standard insectary conditions at a temperature of between 24 and 28 °C with 65–85% relative humidity and under a 12:12 photoperiod of natural light. Mosquito larvae were reared in larval trays and fed on Tetramine ad libitum. Larval water was changed every three days until pupation. Emerged adults were kept in Bugdom cages while being given 10% sugar solution for 3–5 days before bioassays.

DNA extraction and molecular genotyping

For F0 mosquitoes, except for the October 2021 collection, the head and thorax were used for DNA extraction while for the F1s, whole mosquitoes were used. For all DNA extractions, the LIVAK protocol50 was used followed by storing the DNA samples in a − 20 °C freezer. To evaluate the vector bionomics; DNA from F0 mosquitoes were used to assess the species composition and sporozoite infection rates as well as resistance marker frequencies in the population. The species composition of the An. funestus population was assessed using the An. funestus species cocktail PCR51 and sporozoite infection rates were assessed using real-time Taqman PCR52. Sporozoite infection rates were assessed in the 524 mosquitoes that were identified by species in both oviposited and non-oviposited mosquitoes.

For the resistance makers, we sampled 30–40 mosquitoes from the 524 mosquitoes to assess the frequency of resistance makers in the population. We genotyped eight different validated markers; Cyp6P9a, Cyp6P9b, L119F-Gste2, N485I-Ace1, A296S-Rdl, 4.3Kb-SV, 6.5Kb-SV and G454A-Cyp9k1. For the Cyp6P9a, Cyp6P9b and L119F-Gste2 markers, we designed new methods using the Locked Nucleic Assay (LNA)-based qPCR technique53,54 from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Inc. to allow high throughput genotyping. The LNA-based protocols for these three markers are described in detail in the Supplementary section (Supplementary file 1). The remaining markers were genotyped using protocols described previously; N485I-Ace143, A296S-Rdl44, 4.3Kb-SV38, 6.5Kb-SV37 and G454A-Cyp9k136.

Insecticide susceptibility tests

We conducted a series of bioassays to fully characterise the resistance of An. funestus populations at all the time points except for November 2023 due to low number of mosquitoes caused by insectary rearing conditions. From the emerged adult F1s, 3- to 5-day-old female mosquitoes were used for WHO tube assays, WHO cone assays, Bottle assays and Tunnel Tests using standardised protocols55,56. We examined the temporal patterns in insecticide resistance against standard diagnostic concentrations, including intensity assays and new bednets. Table 1 summarises the different bioassay tests we conducted using several insecticides and LLINs.

Assessment of the transcriptomic profile of key genes

To temporally understand the mechanisms driving resistance escalation, we extracted RNA from alive mosquitoes after exposure to 1×, 5× and 10× alpha-cypermethrin and 1× permethrin while using unexposed 2021 mosquitoes and FANG lab strain as a field and susceptible control respectively. Relative to FANG, we examined the gene expression profile of six key genes that have previously been associated with pyrethroid resistance. We looked at the expression patterns of CYP9K1 (Vectorbase designation: AFUN007549), CYP6P9A (AFUN015792), CYP6P9b (AFUN015889), CYP6P5 (AFUN015888), CYP6M7 (AFUN007663) and GSTe2 (AFUN015809), genes that have been largely implicated in pyrethroid resistance in Uganda32,57,58. Briefly, in each group, total RNA was extracted from three batches of ten mosquitoes using the PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit, (ThermoFisher Scientific, United Kingdom), followed by cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription using the SuperScript® III First-Strand Synthesis System, ThermoFisher (United Kingdom) and then finally quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) as previously described59. Gene expression was assessed and compared between the different groups by using the 2−ΔΔCT method60 to calculate the relative expression and fold change after normalisation using the housekeeping genes ribosomal protein S7 (RPS7) (AFUN007153-RA) and Actin (AFUN006819-RA) as used previously20,35.

Data analysis

Field and laboratory data were entered into an Excel sheet and analysed using R software (ver. 1.4.1106) packages to plot counts, proportions and frequencies. Gene expression data was plotted using R and Analysis of variance (ANOVA) online was used to compare the statistical difference in mean fold change expression levels between groups.

Results

Mosquito abundance and species composition

The dominant malaria vector was An. funestus consistently from 2021, 2022 and 2023 with approximately more than 1000 individuals representing 55–71% of the collected mosquitoes (Figure 2A). From the collections, we sampled 40–60 field female mosquitoes (F0) from those that oviposited and did not oviposit to evaluate the species composition giving a total of 572 samples. The results from samples that amplified (n = 524) revealed a variation in species composition temporally (Fig. 2B). An. funestus s.s was still the most abundant species throughout the time periods (80–100% abundance) with significant relative reduction only in May 2023 in oviposited females (57.41%) and November 2022 in non-oviposited females (62.5%). We also detected other secondary species and these included; An. leesoni, An. parensis, An. rivulorum, An. rivulorum-like and An. vaneedeni at a relatively smaller proportions in oviposited compared to non-oviposited females. Interestingly, there was a high proportion of hybrids detected in the populations of An. funestus from Mayuge. However, these hybrids were not detected at all time points and the highest abundance was observed in May 2023 (33.3%) in oviposited females. Hybridisation species structure was very heterogenous although mostly comprised of An. funestus s.s and other secondary species (Supplementary file 1).

Plasmodium sporozoite infection rates

Sporozoite infections were predominantly P. falciparum (94.5%) and no mixed infections were detected in the samples (Fig. 3). In October 2021, sporozoite rates were 11.70% and 1.06% for P. falciparum and other Plasmodium species respectively in oviposited females. In March 2022, a peak infection rate was observed where 20.41% of the infections were P. falciparum in oviposited females while only 2.27% were observed in non-oviposited females. The percentage of other Plasmodium species was 2.04% in oviposited females and 0% in non-oviposited females. In November 2022, only sporozoite infection rates for P. falciparum were observed in oviposited females at 8.77%, while 2.08% was observed in non-oviposited females. The mosquito infection rates by P. falciparum in oviposited females dropped drastically from 7.41% in May 2023 to 1.67% in November 2023 and 1.64% and 0% in non-oviposited females in the same periods with no further observations of other Plasmodium species. Overall, oviposited females significantly (P < 0.001) carried the highest burden of sporozoite infection (91.7%) compared to non-oviposited females (8.3%). Within the parasite species, An. funestus s.s significantly (P < 0.001) carried the highest burden of sporozoites (87.2%) compared to other species (12.8%).

Insecticide resistance profile

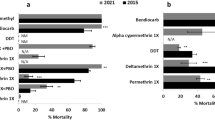

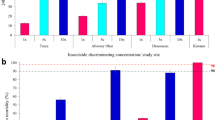

Insecticide resistance and intensity were more pronounced in type II pyrethroids (deltamethrin and alpha-cypermethrin) compared to type I pyrethroid (permethrin) (Fig. 4). Increasing dosage greatly increased mortality with permethrin (average mortality; 1× = 10.8%, 5× = 55.1% and 10× = 83.3%) but not so much with alpha-cypermethrin (average mortality; 1× = 6.6%, 5× = 36.4% and 10× = 51.2%) and deltamethrin (average mortality; 1× = 8.2%, 5× = 44.6% and 10× = 67.9%) (Figure 4). Similarly, pre-exposure to synergists notably increased the mortality with permethrin with PBO (average mortality = 80.5%) compared to DEM (average mortality = 31.8%) and DEF (average mortality = 41.4%) although full restoration of susceptibility was not achieved. However, a lower increase in mortality especially with PBO was observed with alpha-cypermethrin (average mortality; PBO = 55.6%, DEM = 31.8% and DEF = 26.8%) and deltamethrin (average mortality; PBO = 55.5%, DEM = 24.5% and DEF = 48.4%). The temporal pattern in pyrethroid resistance was variable between different months but almost alternating around the same point. However, there was a noticeable trend in decrease of mortality to permethrin at higher doses (Fig. 4). Similar patterns were observed with the knockdown where rates were almost reflective of the observed mortality (Supplementary Figure 2).

Mortality rates from F1 bioassays against pyrethroids. Point mortality rates of An. Funestus mosquitoes exposed to pyrethroids-only and pyrethroids + synergists. Error bars in the line graph and bar chart indicate confidence intervals calculated by SEM and NA indicate tests that were not performed. The red dotted horizontal line is 90% mortality cut-off, below which is confirmed resistance.

Insecticide resistance patterns against other insecticides were more consistent except for DDT insecticide. Mortality rates for DDT drastically decreased from 64.7% in 2021 to 17.5% in 2023 (Fig. 5A). This pattern was also observed with the knockdown rates (Supplementary Figure 3A). Mortality rates for Bendiocarb were consistent over the years with an average of 82.4% but the knockdown rate was very high (up to 100% in most months) (Supplementary Figure 3A). By contrast, mosquitoes were fully susceptible to organophosphates (pirimiphos-methyl and fenitrothion). Similarly, although there was largely no resistance to neonicotinoids and pyrroles, there were signals of reduced susceptibility as observed by decreased mortality for clothianidin in May 2023 (Fig. 5B) and relatively low knockdown rates throughout the years (Supplementary Figure 3B).

Mortality rates from F1 bioassays against insecticides used in IRS and bednets. Point mortality rates for insecticides DDT, Bendiocarb, Pirimiphos-methyl (A); clothianidin and chlorfenapyr (B) and LLINs (C). Error bars in both line and bar graph indicate confidence intervals calculated by SEM. NA indicate tests that were not performed. The dotted red horizontal line is 90% mortality cut-off, below which is confirmed resistance.

When mosquitoes were exposed to bednets, dual-active ingredient LLINs produced higher mortality rates. Permanet 3.0 Top produced a very high kill rate (average mortality = 100%), followed by Olyset Plus (average mortality = 79.1%) (Figure 5C). However, unlike Permanet 3.0 Top, knockdown rates (average = 93.4%) (Supplementary Figure 5) for Olyset Plus were higher than the mortality rates. Although these rates did not vary considerably between the months of collection, there was a noticeable trend in the decrease of efficacy of Olyset Plus (Fig. 5C). Among the dual active ingredient nets, the chlorfenapyr-based Interceptor G2, produced a mortality rate of 70.1% in November 2022 (Supplementary Figure 4) while Royal Guard had an average mortality rate of 53.9% with slightly reduced efficacy in November 2023. Single active ingredient LLINs had very poor efficacy throughout the months of testing with higher mortalities observed only in March 2022. Duranet (average mortality = 12.2%) and Interceptor (average mortality = 11.4%). Knockdown was seemingly higher than mortality for most of the single-ingredient LLINs (Supplementary Figure 5).

Allele frequency of resistance markers

There was no drastic change in the frequency of resistance markers over the five time points and the homozygous resistant genotypes (RR) of most markers were either very low, fixed or absent in the population. Most of the notable variations were seen in November 2022 and May 2023 (Figure 6). We did not detect the 6.5kb-SV marker in any of the samples using the current method.

Insecticide resistance marker prevalence across five time points from 2021 to 2023. Point prevalence of major insecticide resistance markers in An. funestus. The different genotypes are shown in brackets and represented as; SS for homozygous susceptible/wild type, RS for heterozygous and RR for homozygous resistant/mutant.

The frequency of the RR genotype of the L119F-Gste2 marker was at very low frequency with no major changes between 2021 and 2023 though there was an increase in RS (heterozygous) genotype in oviposited females (40%) in November 2022 which was also marked with a slight increase of RR genotype in non-oviposited females (8.11%). Similar observations were seen with Cyp6P9a and Cyp6P9b markers where the frequency of RR and RS genotypes were very low with some few variations in mosquitoes that oviposited but slightly higher frequencies in non-oviposited females which will require further investigation.

The G454A-Cyp9k1 and 4.3kb-SV markers were generally fixed in the population but some variations in frequency were observed. In May 2023 among the oviposited females, the frequency for RR genotype for 4.3kb-SV was only ~70% with the detection of RS and SS (homozygous susceptible) genotypes in the population but the G454A-Cyp9k1 marker remained fixed throughout. In non-oviposited females, all genotypes for 4.3kb-SV were detected at all time points except November 2023 and this included a detection of only 75% of RR genotype in November 2022. The RR genotype of G454A-Cyp9k1 was fixed throughput except in November 2022 where the frequency was only at 80%.

Uniquely, we have detected the presence of resistant alleles for A296S-Rdl and N485I-Ace1 in An. funestus populations but at very low frequencies. These makers were detected only in May 2023 and November 2023. For the N485I-Ace1, only the RS genotype was detected in the population (13.6% in oviposited and 5.13% in non-oviposited) while for the A296S-Rdl, both RS and RR genotypes were detected (RS = 21.43%, RR = 4.35% in oviposited) with the latter being detected only in November 2023. These results mark the first-ever report of detection of the resistant alleles for A296S-Rdl and N485I-Ace1 in East Africa.

Transcriptomic profile of key genes

Fold change (FC) analysis revealed the overexpression of CYP9K1 and the two duplicated genes (CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b) as the key drivers of resistance although only CYP9K1 had consistent results (Fig. 7). The fold change (FC) analysis showed that CYP9K1 gene was consistently overexpressed across the different exposure groups and time periods. For example, in mosquitoes exposed to permethrin, the FC for CYP9K1 gene was 78.7 ± 11.4 in 2021 and 62.7 ± 18.2 in 2022. Similarly, for alpha-cypermethrin, the FC ranged from 65.0 ± 15.9 in 2021 to 45.8 ± 12.1 in 2023, with no significant differences between exposure groups or doses (One-way ANOVA; df = 12, F = 0.6, P = 0.674). However, there was a significant difference in gene expression temporally, with higher levels observed in 2021 than in 2022 (One-way ANOVA; df = 12, F = 21.6, P = 0.00024). The CYP6M7 gene also showed consistent expression but at lower levels, with FC values around 17.9 ± 4.2 in 2021 and 15.4 ± 1.1 in 2023 for alpha-cypermethrin. Similarly, CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b were highly upregulated in 2021 (e.g., CYP6P9A FC = 32.6 ± 12.4 for alpha-cypermethrin 1× in 2021 and CYP6P9b FC in alpha-cypermethrin 1× was 13.6 ± 3.2 in 2021. Both genes showed higher expression with type II pyrethroids and increased doses, such as CYP6P9A FC reaching 88.7 ± 21.5 for alpha-cypermethrin 5× in 2021. The CYP6P5 gene followed a similar pattern to CYP6P9b, with FC dropping from 23.7 ± 10.1 in 2021 in unexposed mosquitoes. Meanwhile, GSTE2 had very low FC (< 3 ± 0.5) and did not show significant changes (P = 0.2611) in expression across the different exposure groups and time points.

Fold change analysis of the expression of key genes across three years. Box plot shows the mean fold change expression of six key genes from three biological replicates. Error bars represent SEM. Abbreviated labels on the x-axis are; “Alphacyp” = Alpha-cypermethrin and “Perm” = Permethrin with the corresponding insecticide intensity of 1×, 5× and 10× as explained in Table 1. NA means the group was no assessed. Genes CYP6P9A, CYP6P9b and CYP6P5 were not analysed in 2023.

Discussion

Insecticide resistance is the biggest threat to the continued and sustainable use of insecticide-based mosquito control tools. Worrying levels of intense insecticide resistance have been widely reported further shrinking the choices available for effective vector tools. Practically, insecticide resistance is very dynamic and vector populations will respond to the applied selection pressure which consequently alters the population structure. Our study monitored insecticide resistance-associated dynamics for an extended time in An. funestus populations from eastern Uganda during a period when different vector control tools were being deployed by the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP).

Temporal dynamics in the bionomics of An. funestus species in Uganda reveal population admixture and changes in sporozoite infection rates

Since 2010, malaria transmission has been principally driven by An. funestus especially in East and Southern Africa, largely attributable to the scale-up of LLINs over the last 15 years46. It is argued that An. funestus was likely less affected by insecticides used for treatment of bednets notably pyrethroids due the ability to rapidly develop strong resistance to Insecticide treated net (ITNs). This resistance, combined with its preference for feeding on humans, long lifespan, tendency to take multiple blood meals, and behaviours such as breeding throughout the year61, resting indoors and biting in the early morning62,63, enhanced its survival and chances to be highly and efficiently infected with Plasmodium parasites hence driving transmission of malaria. Furthermore, when bednets are in use, An. funestus has been observed to be capable of penetrating through the net to blood feed64. Consistent with this, the population of malaria vectors we surveyed were predominantly An. funestus s.l which is also consistent with the study conducted in 20209. However, the temporal investigation revealed that the population of An. funestus may not be stable with only one species i.e. An. funestus s.s dominating. We observed a reasonable presence of other sibling species and notably, high but unstable hybridization rates signalling population admixture among An. funestus s.l. Similar observations were observed in the Chikwawa region of Malawi in 2014 and 2021 which also happened to coincide with intense and multiple insecticide resistance in Malawi11,65. These changes in An. funestus population structure seems to reflect a response to the different vector control tools that were rolled out by NMCP in Uganda. In 2019-2020, when Actellic (pirimiphos-methyl) was the principle insecticide used for IRS in eastern Uganda2, the population was mainly An. funestus s.s in Mayuge20. Uganda switched to a clothianidin-based formulation in 2020–2022 for IRS, which was marked by a dramatic malaria resurgence mainly driven by clothianidin-tolerant An. funestus2. During the clothianidin IRS period, An. funestus thrived, leading to an apparent increase in their abundance2 hence providing a suitable pool and condition for population admixture. Hybridization rates in An. funestus population occur more often than in An. gambiae population and are corridors of introgression of genetic elements such as resistance genes into the main vector population. However, when Actellic was re-introduced in March 2023, by November 2023 the population was almost similar to that observed in 2020 with the majority being An. funestus s.s. The impact of the different IRS periods in Uganda is accurately aligned with this study and was probably a big factor that influenced mosquito bionomics in the area. For instance, sporozoite rates were higher than observed in February 202020 with a peak in March 2022 which happened to coincide with the peak of the malaria resurgence in eastern Uganda. Shortly after the re-introduction of Actellic, we observed a reduction in sporozoite rates in May 2023 with a further drastic decrease by November 2023 to a lower rate similar to that observed in Tororo and Busia around the same period2.

Interestingly, we observed higher sporozoite rates in oviposited mosquitoes compared to non-oviposited mosquitoes. It is unclear why this was the case given that the opposite was observed in February 2020 by Tchouakui et al. A probable explanation is likely linked to the effective IRS campaigns and distribution of LLINs conducted between 2018 and 2020 on the fitness of the mosquito populations. The naturally selected clothianidin-tolerant An. funestus populations during the malaria resurgence period must have been fitter since this was an entirely new formulation that had never been used in Uganda. Studies have shown that increased insecticide selection pressure on mosquitoes can lead to higher sporozoite infection rates66 and resistant mosquitoes generally tend to carry a higher parasite burden67,68,69,70,71 which increases their egg oviposition rates70 This interplay between mosquito parasite infection and oviposition is very complex to understand. Parasites such as Plasmodium are known to manipulate their hosts to sometimes bring forth oviposition to allow another cycle of blood-feeding which potentially increases the chance of being transmitted through the next blood meal72.

Genetic mechanisms and drivers of insecticide resistance in An. funestus from Uganda and their temporal changes between 2021 and 2023

Despite the visible changes in the mosquito population and bionomics, there was no marked effect on the allele frequency of most of the resistance markers except the A296S and N485I markers. Additionally, the allele frequency of the markers cannot explain the observed phenotypic resistance or parasite infection. Pyrethroid resistance intensification was first reported in Uganda in 202020. Since 2020, not much has changed but there are indications of further decreasing efficacy of permethrin at 10x diagnostic dose which might also be further affecting the performance of Olyset Plus. Additionally, the escalation is worse with type II pyrethroids, possibly alluding to the different resistance mechanisms involved. Indeed, PBO synergistic assays revealed higher mortality rates with permethrin exposure than alpha-cypermethrin and deltamethrin.

In May 2023, we detected both mutant alleles for Rdl-A296S and Ace1-N485I markers for the first time. Only Rdl-A296S had a temporal increase in the homozygous mutant allele in November 2023 while the Ace1-N485I marker was only detected in heterozygous form and seemed unstable. The detection of these two markers possibly indicates an introgression that might have occurred during the resurgence or a selection pressure or both with the period likely earlier than May 2023. The Rdl-A296S marker has been detected before in Uganda in 200944 but was not detectable by 202020. The Rdl-A296S is a West African marker associated with dieldrin resistance hence it’s not associated with any of the insecticides that are currently used in Uganda. Contrastingly, it is the first time the Ace1-N485I marker has been detected in Uganda. The marker was first detected only in Southern Africa43 where it conferred cross-resistance to pyrethroids and carbamates. Currently, the intense pyrethroid resistance and moderate carbamate resistance detected in Uganda cannot possibly be associated with the Ace1-N485I marker due to its very low frequency and because carbamate was discontinued for IRS in 2016. So, it is unlikely that there will be further selection of this marker unless there is an unknown pressure from agricultural pesticides or other sources which will also entirely depend on the fitness costs involved with harbouring the allele.

It appears that most of the mechanisms conferring pyrethroid resistance in Uganda exist largely within the rp1 QTL including the 4.3kb transposon31,32,38 and within the CYP9K1 haplotype32,36. Indeed, gene expression analysis revealed stable upregulation of CYP9K1 and CYP6M7 in An. funestus population from eastern Uganda but it is unlikely they are involved in pyrethroid resistance escalation hence, other key mechanisms exist. This is further supported by evidence where the G454A CYP9K1 marker and 4.3-Kb SV are already fixed in Uganda hence, they can’t explain the resistance escalation observed although it is currently unclear how far these markers have spread within Uganda since their distribution can vary within the country, as seen in Cameroon and across geographical locations36,73. Mechanisms driving pyrethroid resistance in Uganda seem to be very complex to map especially in eastern Uganda largely because of the different selection pressures arising from the rotation of multiple malaria control interventions including both LLINs and IRS2,15 and agricultural pesticides. For instance, between 2011 and 2012, microarray-based transcriptomic analysis revealed that key genes expressed in An. funestus populations from Uganda included CYP9K1, CYP6M7 with significant variations in expression levels of CYP6M7 between northern and eastern regions58 but low relative expression of GSTE2, CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b genes74. In 2021-2022, we found similar results but contrastingly, high expression of CYP6P9A and CYP6P9b genes which was also similar to what was observed in 202020. However, the high overexpression did not associate with the southern African CYP6P9a/b markers34,35 which were at very low frequencies, but rather is associated with the presence of the 4.3kb structural variants found only in East and Central Africa38.

Impact of malaria control programs in Uganda on insecticide resistance in An. funestus

Malaria control campaigns in Uganda since 2009 has been dominated by the distribution of bednets every three years with the key introduction of PBO nets in 2017 which were then complemented by other types of bednets like Pyriproxyfen-based nets in 2020 and Chlorfenapyr-based nets in 2023. Despite the recent reduction in the efficacy of especially PBO nets12,18,75, these LLINs were largely effective including in reducing vector abundance15,76. Indeed, cone assays revealed that PBO and chlorfenapyr nets offer a very high killing effect on highly resistant An. funestus populations although efficacy in the field is better measured by experimental hut trials77,78. Supplementary to LLINs, Uganda also conducts IRS campaigns in high transmission areas79 and since 2009, rotation was made between Actellic and Bendiocarb and then recently introducing Fludora Fusion and Sumishield in 2020–2022 before switching back to Actellic in 20232. Actellic remains the only fully effective IRS formulation in Uganda as also witnessed by the full susceptibility of the multi-resistant An. funestus populations to pirimiphos-methyl in this study. However, there is resistance to Bendiocarb which might have occurred earlier or shortly before the formulation was discontinued in 2016. Carbamate resistance is now possibly being driven by cross-resistance with pyrethroids-associated genes as seen in Malawi43 with the selection pressure from bednets. Additionally, although An. funestus were largely susceptible to clothianidin, there were signals of resistance to these chemicals as witnessed in this study over time which is in line with the recent surge in malaria cases driven by An. funestus when clothianidin-based formulations were introduced2. The mechanisms that drove clothianidin tolerance/resistance were not further investigated. Although An. funestus populations remains largely susceptible to clothianidin80, resistance has been reported in An. gambiae from Cameroon81. A recent study has shown that cross-resistance can occur with pyrethroids with an association with the L119F-GSTe2 marker80. However, the low frequency of the L119F-GSTe2 marker and low expression of the GSTE2 gene observed in this study cannot explain the observed phenotypic resistance including against pyrethroids, DDT or bednets. Besides cross-resistance to clothianidin, the L119F-GSTe2 marker is known to confer DDT resistance in West Africa42 with cross-resistance to pyrethroid further decreasing the efficacy of bednets18. Contrastingly, studies have shown that the L119F-GSTe2 marker together with key CYPs such as CYP6P9a/b markers show a negative association with chlorfenapyr82,83. We did not detect any chlorfenapyr resistance which was also synonymously evidenced by the high killing effect of Interceptor G2, a chlorfenapyr-based bednet, in this study. One major reason for detecting no chlorfenapyr resistance could be that the key mechanisms which are mainly CYPs in An. funestus are rather promoting chlorfenapyr susceptibility rather than resistance as shown recently in Anopheles vectors83. It will therefore be interesting to see how the mosquito population structure and resistance patterns/mechanisms change after the 2023 rollout of approximately 330,000 chlorfenapyr-based bednets in Mayuge district and country-wide.

Conclusion

The evolution of insecticide resistance is very dynamic, often rapid and can lead to mosquito population changes. Here, we see how complex insecticide resistance and its associated mechanisms is in An. funestus from Uganda which might principally be driven by overexpression of multiple metabolic genes with key genetic markers. The deployment of various insecticide-based tools in Uganda, primarily pyrethroid LLINs, does not seem to significantly affect the allele frequency of genetic markers at least in Mayuge district potentially due to the near fixation of major P450 resistance alleles. However, the IRS program seems to have a real-time impact on mosquito population structure and bionomics highlighting the importance of rotating interventions and implementing new insecticides. Upregulation of multiple key gene families such as CYP9K1, CYP6P9A/b, CYP6P5 and CYP6M7 seems to be the major strategy deployed by Ugandan An. funestus to counter pyrethroids and possibly other insecticides. This means that any adaptive selection of genetic variants such as SNPs and transposons will likely be linked to significant overexpression of major genes as seen with the CYP9K1 G454A single allele and 4.3-Kb transposon in An. funestus36,38, and the CYP6P4 triple mutant allele with Zanzibar (ZE) transposon in An. gambiae84 from Uganda. This selective advantage of such SNPs or transposons would lead to fixation within a short time and remain fixed as long as the same selection pressure is applied and there is minimal fitness cost attached to the genetic variant. It is very likely that within the key upregulated genes in An. funestus populations from Uganda, other key genetic variants exist and auxiliary temporal genomic monitoring should continue to identify these. Additionally, further studies to investigate mechanisms of resistance such as apparently seen with clothianidin and bendiocarb are recommended.

Data availability

All datasets generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Change history

15 February 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article was published incorrectly under licence CC BY-NC-ND. The licence has been corrected to CC BY.

References

WHO. World Malaria Report 2023. (2023).

Kamya, M. R. et al. Dramatic resurgence of malaria after 7 years of intensive vector control interventions in Eastern Uganda. PLOS Glob. Public Health 4, e0003254 (2024).

WHO. IMPLICATIONS OF INSECTICIDE RESISTANCE ON MALARIA VECTOR CONTROL Implications of Insecticide Resistance on Malaria Vector Control Project. (2016).

Riveron, J. M. et al. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: An update at a global scale. in Towards Malaria Elimination—A Leap Forward (InTech, 2018). 7, 149–175 https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78375.

Hancock, P. A. et al. Mapping trends in insecticide resistance phenotypes in African malaria vectors. PLoS Biol. 18(6), e3000633 (2020).

Knox, T. B. et al. An online tool for mapping insecticide resistance in major Anopheles vectors of human malaria parasites and review of resistance status for the Afrotropical region. Parasites Vectors. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-76 (2014).

Bertozzi-Villa, A. et al. Maps and metrics of insecticide-treated net access, use, and nets-per-capita in Africa from 2000–2020. Nat. Commun. 12, 3589 (2021).

Lindsay, S. W., Thomas, M. B. & Kleinschmidt, I. Threats to the effectiveness of insecticide-treated bednets for malaria control: Thinking beyond insecticide resistance. Lancet Glob. Health. 9, e1325–e1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00216-3 (2021).

Tchouakui, M. et al. Pyrethroid resistance aggravation in Ugandan malaria vectors is reducing bednet efficacy. Pathogens 10, 415 (2021).

Oruni, A. et al. (2024) Pyrethroid resistance and gene expression profile of a new resistant An. gambiae colony from Uganda reveals multiple resistance mechanisms and overexpression of Glutathione-S-Transferases linked to survival of PBO-pyrethroid combination. Wellcome Open Res. 9, 13.

Menze, B. D. et al. Marked aggravation of pyrethroid resistance in major malaria vectors in Malawi between 2014 and 2021 is partly linked with increased expression of P450 alleles. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 660 (2022).

Ngongang-Yipmo, E. S. et al. Reduced performance of community bednets against pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles funestus and Anopheles gambiae, major malaria vectors in Cameroon. Parasit. Vectors 15, 230 (2022).

Farnham, A. W. The mode of action of piperonyl butoxide with reference to studying pesticide resistance. Piperonyl. Butoxide. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-012286975-4/50014-0 (1999).

Protopopoff, N. et al. Effectiveness of a long-lasting piperonyl butoxide-treated insecticidal net and indoor residual spray interventions, separately and together, against malaria transmitted by pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes: A cluster, randomised controlled, two-by-two factorial design trial. Lancet 391, 1577–1588 (2018).

Maiteki-Sebuguzi, C. et al. Effect of long-lasting insecticidal nets with and without piperonyl butoxide on malaria indicators in Uganda (LLINEUP): Final results of a cluster-randomised trial embedded in a national distribution campaign. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 247–258 (2023).

Staedke, S. G. et al. Effect of long-lasting insecticidal nets with and without piperonyl butoxide on malaria indicators in Uganda (LLINEUP): A pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial embedded in a national LLIN distribution campaign. Lancet 395, 1292–1303 (2020).

Martin, J. L. et al. Bio-efficacy of field aged novel class of long-lasting insecticidal nets, against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors in Tanzania: A series of experimental hut trials. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.21.23297289 (2024).

Menze, B. D. et al. An experimental hut evaluation of PBO-based and pyrethroid-only nets against the malaria vector Anopheles funestus reveals a loss of bed nets efficacy associated with GSTe2 metabolic resistance. (2020).

Riveron, J. M. et al. Escalation of pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus induces a loss of efficacy of piperonyl butoxide-based insecticide-treated nets in mozambique. J. Infect. Diseases 220, 467–475 (2019).

Tchouakui, M. et al. Pyrethroid resistance aggravation in Ugandan malaria vectors is reducing bednet efficacy. Pathogens 10(4), 415 (2021).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Escalating pyrethroid resistance in two major malaria vectors Anopheles funestus and Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) in Atatam, Southern Ghana. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 799 (2022).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. The duplicated P450s CYP6P9a/b drive carbamates and pyrethroids cross-resistance in the major African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. PLoS Genet. 19(3), e1010678 (2023).

WHO. Prequalified lists: vector control products (website). Geneva: World Health Organization 2021. World Health Organisation (2021).

Tomizawa, M. & Casida, J. E. Neonicotinoid insecticide toxicology: Mechanisms of selective action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 45, 247–268 (2005).

Raghavendra, K. et al. Chlorfenapyr: A new insecticide with novel mode of action can control pyrethroid resistant malaria vectors. Malar. J. 10, 16 (2011).

Huang, P. et al. A comprehensive review of the current knowledge of chlorfenapyr: Synthesis, mode of action, resistance, and environmental toxicology. Molecules. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28227673 (2023).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Mapping a Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) conferring pyrethroid resistance in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. 14, 1–14 (2007).

Irving, H., Riveron, J. M., Ibrahim, S. S., Lobo, N. F. & Wondji, C. S. Positional cloning of rp2 QTL associates the P450 genes CYP6Z1, CYP6Z3 and CYP6M7 with pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Heredity (Edinb.) 109, 383–392 (2012).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Two duplicated P450 genes are associated with pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles funestus, a major malaria vector. 452–459 (2009) https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.087916.108.target.

Wondji, C. S., Hearn, J., Irving, H., Wondji, M. J. & Weedall, G. RNAseq-based gene expression profiling of the Anopheles funestus pyrethroid-resistant strain FUMOZ highlights the predominant role of the duplicated CYP6P9a/b cytochrome P450s. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 12(1), jkab352 (2022).

Weedall, G. D. et al. An Africa-wide genomic evolution of insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus involves selective sweeps, copy number variations, gene conversion and transposons. PLoS Genet. 16(6), e1008822 (2020).

Hearn, J. et al. Multi-omics analysis identifies a CYP9K1 haplotype conferring pyrethroid resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in East Africa. Mol. Ecol. 31, 3642–3657 (2022).

Ingham, V. & Nagi, S. Genomic proling of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: Insights into molecular mechanisms. (2024) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3910702/v1.

Weedall, G. D. et al. A cytochrome P450 allele confers pyrethroid resistance on a major African malaria vector, reducing insecticide-treated bednet efficacy. Sci. Transl. Med. 11(484), eaat7386 (2019).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. Cis-regulatory CYP6P9b P450 variants associated with loss of insecticide-treated bed net efficacy against Anopheles funestus. Nat. Commun. 10, 4652 (2019).

Djoko Tagne, C. S. et al. A single mutation G454A in P450 CYP9K1 drives pyrethroid resistance in the major Short title: CYP9K1 single mutation and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles funestus. bioRxiv. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.22.590515.

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. A 6.5-kb intergenic structural variation enhances P450-mediated resistance to pyrethroids in malaria vectors lowering bed net efficacy. Mol. Ecol. 29, 4395–4411 (2020).

Mugenzi, L. M. J. et al. (2024) Association of a rapidly selected 4.3 kb transposon-containing structural variation with a P450-based resistance to pyrethroids in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. PLoS Genet. 20, e1011344.

WHO/GMP. Global plan for insecticide resistance management in malaria vectors. World Health Organization Press. 13 (2012).

Corbel, V. & Guessan, R. N. Distribution, mechanisms, impact and management of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: A pragmatic review. Anopheles Mosquitoes New Insights into Malaria Vectors 813 (2013) https://doi.org/10.5772/3392.

Odero, J. O. et al. Genetic markers associated with the widespread insecticide resistance in malaria vector Anopheles funestus populations across Tanzania. Parasit Vectors 17, 230 (2024).

Riveron, J. M. et al. A single mutation in the GSTe2 gene allows tracking of metabolically based insecticide resistance in a major malaria vector. Genome Biol. 15, R27 (2014).

Ibrahim, S. S., Ndula, M., Riveron, J. M., Irving, H. & Wondji, C. S. The P450 CYP6Z1 confers carbamate/pyrethroid cross-resistance in a major African malaria vector beside a novel carbamate-insensitive N485I acetylcholinesterase-1 mutation. Mol. Ecol. 25, 3436–3452 (2016).

Wondji, C. S. et al. Identification and distribution of a GABA receptor mutation conferring dieldrin resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 41, 484–491 (2011).

Odero, J. O. et al. Discovery of knock-down resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus reveals the legacy of persistent DDT pollution. bioRxiv. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.13.584754.

Msugupakulya, B. J. et al. Changes in contributions of different Anopheles vector species to malaria transmission in east and southern Africa from 2000 to 2022. Parasites Vectors. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-06019-1 (2023).

Ministry of Health, U. THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF HEALTH On the road to a Malaria-free Uganda—Second Universal Coverage Mosquito Net distribution Campaign offers hope to Uganda Table Of Contents pg. 1–20 (2018).

Coetzee, M. Key to the females of Afrotropical Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Malar. J. 19, 70 (2020).

Morgan, J. C., Irving, H., Okedi, L. M., Steven, A. & Wondji, C. S. Pyrethroid resistance in an anopheles funestus population from uganda. PLoS One. 5(7), e11872 (2010).

Livak, K. J. Detailed structure of the drosophila melanogaster stellate genes and their transcripts. J. Geophys. Res. 75, 5276–5278 (1989).

Koekemoer, L. L., Kamau, L., Hunt, R. H. & Coetzee, M. A cocktail polymerase chain reaction assay to identify members of the Anopheles funestus (Diptera: Culicidae) group. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hygiene 66, 804–811 (2002).

Bass, C. et al. PCR-based detection of Plasmodium in Anopheles mosquitoes: A comparison of a new high-throughput assay with existing methods. Malar. J. 7, 177 (2008).

Owczarzy, R., You, Y., Groth, C. L. & Tataurov, A. V. Stability and mismatch discrimination of locked nucleic acid-DNA duplexes. Biochemistry 50, 9352–9367 (2011).

You, Y., Moreira, B. G., Behlke, M. A. & Owczarzy, R. Design of LNA probes that improve mismatch discrimination. Nucleic Acids Res. 34(8), e60 (2006).

WHO. Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes, 2nd Edn. (2016).

WHO. Standard Operating Procedure for Testing Insecticide Susceptibility of Adult Mosquitoes in WHO Bottle Bioassays. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352312/9789240043770-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (2022).

Riveron, J. M. et al. The highly polymorphic CYP6M7 cytochrome P450 gene partners with the directionally selected CYP6P9a and CYP6P9b genes to expand the pyrethroid resistance front in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus in Africa. BMC Genom. 15, 817 (2014).

Sandeu, M. M., Mulamba, C., Weedall, G. D. & Wondji, C. S. A differential expression of pyrethroid resistance genes in the malaria vector Anopheles funestus across Uganda is associated with patterns of gene flow. PLoS One 15(11), e0240743 (2020).

Riveron, J. M. et al. Directionally selected cytochrome P450 alleles are driving the spread of pyrethroid resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 252–257 (2013).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108 (2008).

Coulibaly, M. B., Traoré, S. F. & Touré, Y. T. Chapter 3—Considerations for disrupting malaria transmission in Africa using genetically modified mosquitoes, ecology of anopheline disease vectors, and current methods of control. in Genetic Control of Malaria and Dengue (ed. Adelman, Z. N.) 55–67 (Academic Press, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800246-9.00003-X.

Sougoufara, S. et al. Biting by Anopheles funestus in broad daylight after use of long-lasting insecticidal nets: A new challenge to malaria elimination. Malar. J. 13, 125 (2014).

Moiroux, N. et al. Human exposure to early morning Anopheles funestus biting behavior and personal protection provided by long-lasting insecticidal nets. PLoS One 9, 8–11 (2014).

Meza, F. C., Muyaga, L. L., Limwagu, A. J. & Lwetoijera, D. W. (2022) The ability of Anopheles funestus and A. arabiensis to penetrate LLINs and its effect on their mortality. Wellcome Open Res. 7, 265.

Riveron, J. M. et al. Rise of multiple insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus in Malawi: A major concern for malaria vector control. Malar. J. 14, 344 (2015).

Adams, K. L. et al. Selection for insecticide resistance can promote Plasmodium falciparum infection in Anopheles. PLoS Pathog 19(6), e1011448 (2023).

Kabula, B. et al. A significant association between deltamethrin resistance, Plasmodium falciparum infection and the Vgsc-1014S resistance mutation in Anopheles gambiae highlights the epidemiological importance of resistance markers. Malar. J. 15, 289 (2016).

Tchouakui, M. et al. A marker of glutathione S-transferase-mediated resistance to insecticides is associated with higher Plasmodium infection in the African malaria vector Anopheles funestus. Sci. Rep. 9, 5772 (2019).

Alout, H. et al. Interplay between Plasmodium infection and resistance to insecticides in vector mosquitoes. J. Infect. Diseases 210(9), 1464–1470 (2014).

Alout, H. et al. Interactive cost of Plasmodium infection and insecticide resistance in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Rep. 6, 29755 (2016).

Ndiath, M. O. et al. Effects of the Kdr Resistance Mutation on the Susceptibility of Wild Anopheles Gambiae Populations to Plasmodium Falciparum: A Hindrance for Vector Control. http://www.malariajournal.com/content/13/1/340 (2014).

Vézilier, J., Nicot, A., Gandon, S. & Rivero, A. Plasmodium infection brings forward mosquito oviposition. Biol. Lett. 11(3), 20140840 (2015).

Gadji, M. et al. Genome-wide association studies unveil major genetic loci driving insecticide resistance in Anopheles funestus in four eco-geographical settings across Cameroon. bioRxiv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.17.599266.

Mulamba, C. et al. Widespread pyrethroid and DDT resistance in the major malaria vector anopheles funestus in East Africa is driven by metabolic resistance mechanisms. PLoS One 9(10), e110058 (2014).

Tungu, P. K., Michael, E., Sudi, W., Kisinza, W. W. & Rowland, M. Efficacy of interceptor® G2, a long-lasting insecticide mixture net treated with chlorfenapyr and alpha-cypermethrin against Anopheles funestus: Experimental hut trials in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar. J. 20, 180 (2021).

Lynd, A. et al. LLIN Evaluation in Uganda Project (LLINEUP)—Plasmodium infection prevalence and genotypic markers of insecticide resistance in Anopheles vectors from 48 districts of Uganda. medRxiv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.31.23293323.

Ngufor, C., Agbevo, A., Fagbohoun, J., Fongnikin, A. & Rowland, M. Efficacy of Royal Guard, a new alpha-cypermethrin and pyriproxyfen treated mosquito net, against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors. Sci. Rep. 10, 12227 (2020).

Ngufor, C. et al. Evaluating the attrition, fabric integrity and insecticidal durability of two dual active ingredient nets (Interceptor® G2 and Royal® Guard): Methodology for a prospective study embedded in a cluster randomized controlled trial in Benin. Malar. J. 22, 276 (2023).

Presidents Malaria Initiative, U. The PMI VectorLink Project Uganda End of Spray Report 2022 Spray Campaign. February 28–March 26, 2022. www.abtassociates.com (2022).

Assatse, T. et al. Anopheles funestus populations across Africa are broadly susceptible to neonicotinoids but with signals of possible cross-resistance from the GSTe2 gene. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8(5), 244 (2023).

Fouet, C. et al. Clothianidin-resistant Anopheles gambiae adult mosquitoes from Yaoundé, Cameroon, display reduced susceptibility to SumiShield® 50WG, a neonicotinoid formulation for indoor residual spraying. BMC Infect. Dis. 24, 133 (2024).

Tchouakui, M. et al. High efficacy of chlorfenapyr-based net Interceptor® G2 against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors from Cameroon. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 12, 81 (2023).

Tchouakui, M. et al. Substrate promiscuity of key resistance P450s confers clothianidin resistance whilst increasing chlorfenapyr potency in malaria vectors. Cell Rep. 43(8), 114566 (2024).

Njoroge, H. et al. Identification of a rapidly-spreading triple mutant for high-level metabolic insecticide resistance in Anopheles gambiae provides a real-time molecular diagnostic for antimalarial intervention deployment. Mol. Ecol. 31, 4307–4318 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to greatly thank the village health teams (VHTs) and assistants in the villages of operation in Mayuge district who assisted in identifying houses and collecting mosquitoes. In the same fashion, we would like to thank the households that agreed to participate in this study especially since we had to bother them when collecting mosquitoes very early in the morning. We also appreciate the technicians and administration at the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI), Entebbe who helped with organising field works and preparing samples for shipping. Similarly, we greatly appreciate the technicians and colleagues at the Centre for Research in Infectious Diseases (CRID), Cameroon who assisted in rearing mosquitoes and laboratory work.

Funding

This study was funded by BMGF (INV-006003) and Wellcome Trust (217188/Z/19/Z).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S.W. conceived and designed the research. A.O carried out the sample collection, sample processing, mosquito rearing, laboratory analysis, data entry, data analysis and writing the first draft of the manuscript. C.S.D-T assisted with the laboratory and insectary work. M.T., J.K, J.H and C.S.W supervised the study. All authors contributed to the writing of the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read, revised and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oruni, A., Tchouakui, M., Tagne, C.S.D. et al. Temporal evolution of insecticide resistance and bionomics in Anopheles funestus, a key malaria vector in Uganda. Sci Rep 14, 32027 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83689-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83689-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Chlorfenapyr bednets effectively overcome pyrethroid resistance escalation in highly resistant Anopheles malaria vectors in Uganda

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Integrated vector and parasite management for malaria control in high-endemic areas: pummel and pin strategy to prevent malaria setbacks

Malaria Journal (2025)

-

Adjusting vector surveillance for human behaviors reveals Anopheles funestus drove a resurgence in malaria despite IRS with clothianidin in Uganda

Scientific Reports (2025)