Abstract

Currently applicable models for predicting live birth outcomes in patients who received assisted reproductive technology (ART) have methodological or study design limitations that greatly obstruct their dissemination and application. Models suitable for Chinese couples have not yet been identified. We conducted a retrospective study by using a database includes a total of 11,938 couples who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment between January 2015 and December 2022 in a medical institution of southwest China Yunnan province. Multiple candidate predictors were screened out by using the importance scores. Four machine learning (ML) algorithms including random forest, extreme gradient boosting, light gradient boosting machine and binary logistic regression were used to construct prediction models. An initial assessment of the predictive performance was conducted and validated by using cross-validation and bootstrap methods. A total of seven predictors were identified, namely maternal age, duration of infertility, basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), progressive sperm motility, progesterone (P) on HCG day, estradiol (E2) on HCG day, and luteinizing hormone (LH) on HCG day. Of the four predictive models, the random forest model and the logistic regression model were considered to have the optimal performance, with the areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) curves of 0.671 (95% CI 0.630–0.713) and 0.674 (95% CI 0.627–0.720). The Brier scores were 0.183 (95% CI 0.170–0.196) and 0.183 (95% CI 0.170–0.196), respectively. Considering the simplicity of model fitting, we recommend the logistic regression model as the best predictive model for live birth. Furthermore, maternal age, P on HCG day and E2 on HCG day were deemed to have the highest contribution to model prediction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to conceive after at least 12 months of regular unprotected sex, has been a global health problem for a long time1. It is estimated that one in six people of reproductive age worldwide will experience infertility in their lifetime1. In China, there has been a marked increase in infertility over the past two decades2, and currently the infertile population is approximately to one quarter3. Available evidence suggests that infertility significantly impairs quality of life and weakens partnerships when compared to couples without infertility distress4,5,6. Simultaneously, infertility problems can also affect female mental health with worse levels of depression and anxiety7,8.

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) has been rapidly evolving since its emergence in 1978, and its use to help infertile couples achieve pregnancy has led to the birth of more than 8 million newborns worldwide9. ART mainly consists of in vitro fertilization (IVF) with or without intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), embryo transfer, and frozen embryo transfer, of which IVF and/or ICSI are the recommended treatment options for couples with long-term unresolved fertility problems10. However, close to half of couples treated with IVF failed to get pregnant, even after multiple treatment cycles11. Therefore, live birth is the most important outcome of ART treatment. Clinical prediction models on live birth outcome of ART treatment that incorporate multiple patient characteristics are able to help couples establish reasonable psychological expectations and costs, and support consultation between physicians and couples regarding treatment decisions12. Currently, common predictors of live birth outcomes in patients treated by ART included demographic characteristics (maternal age, body mass index, ethnicity, etc.), clinically factors (cause of infertility, duration of infertility, type of infertility, etc.) and laboratory parameters (serum sex hormones, ovarian reserve, number of oocytes collected, sperm motility and morphology, etc.)13,14.

A review of prediction models on live birth outcomes of ART showed that currently available models generally suffer from methodological or study design limitations, such as the use of inefficiently randomized split data for validation, unclear reporting of missing values, only reporting on the discrimination, and the inclusion of pregnant women treated with IVF only15,16,17,18. Although the prediction model developed by Dhillon et al. had the high quality of reporting, it was derived from the UK population, the applicability to other populations remains unclear15,19. Another review noted that only one prognostic prediction study for live births was at low risk of bias, but it only included couples treated with ICSI20,21.

Under such circumstances, we aim to develop and internally validate a prognostic prediction model for live birth by using easily obtainable demographic characteristics and clinical features at the beginning of IVF within a representative, large sample of Chinese patients. Recently, several machine learning (ML) algorithms suitable for classification outcomes such as random forest, extreme gradient boosting, and light gradient boosting have been extensively used for construction of clinical prediction models22,23,24. Thus, we developed models using both traditional regression and these ML algorithms in order to choose the optimal one.

Materials and methods

Data source and study sample

Participants were recruited between January 2015 and December 2022 from couples who accepted ART treatment at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University in southwest China Yunnan Province. Our database contains data on all treatment cycles for 13,620 patients who initiated the first and subsequent IVF with ICSI treatment. Patients were further excluded if: (1) ART initiation before the study period, or; (2) restarted ART after a live birth, or; (3) missing vital information, or; (4) lost to follow-up for at least one year. Finally, 11,486 couples were included in the analysis. Detailed process for selection of patients is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Due to its retrospective nature, informed consent was allowed to be waived by the committee. We confirmed that all methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was reported consistent with the extension and update guideline of the original TRIPOD-2015 (transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis), known as TRIPOD + AI25.

Definitions of outcome and candidate predictors

The primary outcome of interest in this study was whether a live birth occurred during a single ART cycle. Various variables of the patients were extracted as candidate predictors based on previous studies and clinical practice considerations, such as demographic characteristics (couple’s age, ethnicity, maternal body mass index), treatment-related information (duration of infertility, type of infertility, cause of infertility, previous ART cycles, insemination method, starting dosage of gonadotropins (Gn), duration of Gn, and total dosage of Gn), and laboratory test results (basal follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol (E2), and luteinizing hormone (LH), progressive sperm, non-progressive sperm motility, and E2, LH and progesterone (P) on HCG day). Candidate predictors were measured at the time of receiving ART treatment.

Statistical analysis

Firstly, we performed descriptive analyses of the study subjects, and continuous variables were described separately according to the type of distribution, e.g., mean with standard deviation (SD) for a normal distribution and median with inter-quartiles range (IQR) for a non-normal distribution. Differences between groups for continuous variables were tested by t-test or rank-sum test. For categorical variables, frequency (proportion) was used to describe them, and differences between or among groups were compared using the Chi-squared test. In consistent with previous ART studies, we used the same age-stratification criteria (≤ 35 years, 35–39 years, and ≥ 40 years)26,27. We classified the remaining unspecified continuous variables into categorical variables based on quartiles. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions (LR) were fitted to measure the crude and adjusted associations between the candidate predictors and the live birth outcome.

Three machine learning algorithms (random forest, RF; extreme gradient boosting, XGBoost; light gradient boosting machine, LightGBM) were used to further confirm the most important predictors for live birth outcome from candidate predictors screened out by multivariate LR: variables that ranked among the top 6 in at least 2 of the 3 used algorithms were chosen. For the chosen important predictors, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were applied to ascertain their optimal cut-off values with regard to the live birth outcome.

We used the optimal cut-offs to dichotomize all chosen important predictors, then included them into the prediction model by using the four different algorithms (LR, RF, XGBoost, LightGBM). Randomly split sample is considered to be the simplest internal validation approach, but it is sub-optimal because it loses sample information and decreases statistical power28. For this reason, we used two other internal validation approaches (tenfold cross-validation, 500 times bootstrap), which were also recommended by the TRIPOD guideline25. Area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was used to assess discrimination, with the value closer to 1 indicating the greater the ability in discriminating live birth outcomes29. The Brier score was used to estimate the calibration, with the value closer to 0 indicating that the predicted probability of the outcome by the model coincides with the actual probability30.

The statistical significance was set as a two-tailed p < 0.05, except for p < 0.10 for univariate logistic regressions in searching for all possible covariates. All data analysis was done in R software (Version: 4.4.0, Vienna, Austria).

Results

General characteristics of study subjects

As shown in Fig. 1, between 2015 and 2022, there were a total of 13,620 couples included. After data sorting, we excluded participants who reported incomplete data (1682/13,620) or lost to follow-up (452/11,938). The final analysis was based on a total of 11,486 couples with complete information. Altogether 3097 couples successfully reached the live birth outcome, with the live birth rate of 26.96% (95% CI 26.15%-27.79%).

Among all study subjects, husbands were 34.61 ± 5.85 years old, wives were 33.18 ± 5.20 years old, and more than half of the individuals were Han ethnicity (74.04% of husbands and 70.08% of wives), the average duration of infertility was 4.32 ± 3.39 years. The differences between couples with or without live births were statistically significant for age of husband and wife, maternal BMI, duration of infertility, and previous ART cycles. In ovulation induction therapy and laboratory indicators, there were statistically significant differences in all features except for total dosage of Gn, basal E2, and non-progressive sperm motility (Table 1).

Association between factors and live birth

To initially explore the impact of quantitative variables on live births, we classified age as a categorical variable according to the recommended thresholds, whereas the other quantitative variables were classified into categorical variables with four levels based on their quartiles: very low level (< P25), low level (P25–P50), moderate level (P50–P75), and high level (> P75). After fitting univariate binary logistic regression, we included statistically significant variables (p < 0.01) into further multivariate analyses, and the results showed: maternal age and BMI, duration of infertility, previous ART cycles, progressive sperm motility, duration of Gn, total dosage of Gn, basal FSH, E2 on HCG day, and LH on HCG day were significantly associated with live birth (Table 2).

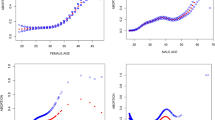

Machine learning results

We incorporate the screened out variables into the multivariate analysis by using three different machine learning algorithms (RF, XGBoost and LightGBM). Seven indicators were identified as the most important in all three algorithms: maternal age, duration of infertility, basal FSH, progressive sperm motility, and E2, LH and P on HCG day (Fig. 2). With the exception of duration of infertility, we identified the optimal cut-off values in predicting the live birth outcomes by using the ROC curves for the rest 6 quantitative variables, and the ascertained cut-offs were: The optimal cut-off values for maternal age, basal FSH, progressive sperm motility, and E2, LH and P on HCG day were 36.97 years for maternal age, 5.57 mIU/mL for basal FSH, 33.52% for progressive sperm motility, 7227.50 pg/mL for E2, 3.04 mIU/mL for LH on HCG day, and 1.33 ng/mL for P on HCG day (Fig. 3).

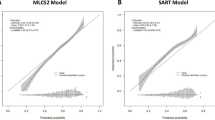

Finally, we built predictive models using only the seven variables mentioned above with logistic regression and three different machine learning algorithms (RF, XGBoost, LightGBM). Both cross-validation and bootstrap methods indicated that LR and RF had the optimal model performance. Specifically, LR yielded an AUROC of 0.671 (95% CI 0.630–0.713) and Brier score of 0.183 (95% CI 0.170–0.196) for cross-validation, and an AUROC of 0.671 (95% CI 0.662–0.683) and Brier score of 0.183 (95% CI 0.179–0.187) for bootstrap. RF had similar discrimination and calibration performance, followed by XGBoost and LightGBM (Table 3). Standardized regression coefficients suggest that among the 7 included indicators, maternal age showed the strongest association with live birth outcome, followed by P on HCG day, E2 on HCG day, whereas basal FSH presented as the weakest predictor (see in Supplementary material, Table S1).

Discussion

In this study, we screened for potential predictors among easily obtained demographic and clinical indicators for live birth in a large sample of Chinese patients who received ART treatment. Based on statistical models and multiple machine learning algorithms, we have identified 7 promising indicators in predicting live birth outcome among ART patients: maternal age, duration of infertility, basal FSH, progressive sperm motility, and E2, LH and P on HCG day. The predictive models based on the 7 identified indicators provided fair and robust prediction accuracy, irrespective of different algorithms. The major findings of our study are expected to provide useful information in helping clinicians better triage patients at the baseline for upcoming ART treatments.

Among the 7 indicators that we screened out, maternal age had the strongest association with live birth outcomes, followed by P on HCG day, E2 on HCG day, LH on HCG day, years of infertility and progressive sperm motility, with the basal FSH showed the weakest influence. It is not surprising to find that maternal age is the strongest predictor of live birth, considering the fact that along with the aging process, especially after the age of 37 years, female fertility will decline rapidly31. This is attributed to the decline in the number of oocytes in women and age-related poor quality of embryos31.

A higher level of P or E2 on HCG day also significantly related to lower probability of live birth. It is hypothesized that elevated follicular-phase P concentration produced by ovarian stimulation-induced multiple follicle growth may contribute to changes in the endometrium, leading to embryo-endometrial asynchrony, which may adversely affect implantation, leading to reduced live birth chances32. However, the role of estradiol levels during HCG days on pregnancy probability is still controversial. A meta-analysis indicated that there was insufficient evidence of an association between high E2 levels and pregnancy probability33. The previous studies have found that high E2 levels on HCG day were significantly predictive of lower live birth rates for couples undergoing frozen embryo transfer34,35. In recent years, basal FSH has been recognized as a predictor of live birth outcome after IVF treatment13. A higher level of basal FSH has also been connected to poor ovarian response36. However, although in this study we have included basal FSH into the final prediction model, as it significantly improved prediction accuracy, unlike maternal age, P and E2 on HCG day, its association with live birth outcome is generally weak. All the above inconsistencies between our study and currently available sparse evidence warrant further investigation.

During development of the prediction model, we initially included previous IVF history in the attempt to adjust for its influence on live birth outcomes. However, previous IVF history presented only negligible influence on live birth and was subsequently eliminated. The general predictive performance of our models, as measured by AUROC, was similar to their comparable models16,17,18. Among all the prediction models that we fitted by using the ML algorithms, the RF model outperformed the others. However, its performance was similar to the LR model in both discrimination and calibration parameters. As the LR model is a widely used generalized linear model that much more easily to be fitted, it should be preferred when comparing with complicated ML models.

Our study results are based on a sufficiently large sample of IVF patients to develop predictive models on live birth outcomes, a large group of easily obtained baseline predictors were screened for. The similar predictive accuracy between the models fitted by different algorithms partly supports the robustness of prediction accuracy for identified factors. Nevertheless, the present study still has some limitations that should be noticed. Firstly, the overall discrimination for the predictive models was not high, only around 67%, which suggests that there are other important predictors that to be found. For instance, serum anti-müllerian hormone (AHM), which reflects ovarian reserve, has been identified as the most important predictor for live birth-related outcomes of ART treatment in existing prediction models37. Also, embryo quality was considered to be a valuable predictor14. However, due to the unavailability of data, we cannot include these important variables into our current prediction models. Secondly, we only screened for baseline indicators that are predictive of live birth outcomes for IVF patients, since the period from treatment inception to live birth is long, it would be interesting to investigate the role of time-varying factors on the IVF outcomes by using dynamic prediction models. Finally, the study sample was derived from a single medical institution by using retrospective study design, therefore information bias and selection bias could not be avoided. Multicenter, prospective studies should be done in the future to externally validate our major findings.

In summary, we constructed prognostic prediction models for the live birth outcome in couples undergoing IVF, with or without ICSI treatment, by using logistic regression and machine learning algorithms. The models resulting from different approaches yielded similar predictive performance, and the logistic regression model was considered to have the best performance and was recommended for further validation. Future studies of longitudinal design and incorporate more meaningful indicators are warranted to validate and improve the prediction accuracy of current models.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical reason but are available from the corresponding authors under the reasonable request.

References

WHO. Infertility. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility (2024).

Qiao, J. Healthy birth—protecting health from the origin of life. Chin. J. Reprod. Contracep. 43, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn101441-20220906-00382 (2023) (in Chinese).

Zhou, Z. et al. Epidemiology of infertility in China: a population-based study. BJOG 125, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14966 (2018).

Klemetti, R., Raitanen, J., Sihvo, S., Saarni, S. & Koponen, P. Infertility, mental disorders and well-being–a nationwide survey. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 89, 677–682. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016341003623746 (2010).

Boulet, S. L., Smith, R. A., Crawford, S., Kissin, D. M. & Warner, L. Health-related quality of life for women ever experiencing infertility or difficulty staying pregnant. Matern. Child Health J. 21, 1918–1926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2307-y (2017).

Kiesswetter, M. et al. Impairments in life satisfaction in infertility: Associations with perceived stress, affectivity, partnership quality, social support and the desire to have a child. Behav. Med. 46, 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2018.1564897 (2020).

Yusuf, L. Depression, anxiety and stress among female patients of infertility; A case control study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 32, 1340–1343. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.326.10828 (2016).

Lakatos, E., Szigeti, J. F., Ujma, P. P., Sexty, R. & Balog, P. Anxiety and depression among infertile women: a cross-sectional survey from Hungary. BMC Women’s Health 17, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0410-2 (2017).

Fauser, B. C. Towards the global coverage of a unified registry of IVF outcomes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 38, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.12.001 (2019).

Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Fertility treatment 2022: preliminary trends and figures. https://www.hfea.gov.uk/about-us/publications/research-and-data/fertility-treatment-2022-preliminary-trends-and-figures/ (2024).

Moragianni, V. A. & Penzias, A. S. Cumulative live-birth rates after assisted reproductive technology. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 22, 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e328338493f (2010).

McLernon, D. J., Steyerberg, E. W., Te Velde, E. R., Lee, A. J. & Bhattacharya, S. Predicting the chances of a live birth after one or more complete cycles of in vitro fertilisation: population based study of linked cycle data from 113 873 women. BMJ 355, i5735. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5735 (2016).

van Loendersloot, L. L. et al. Predictive factors in in vitro fertilization (IVF): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 16, 577–589. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmq015 (2010).

Shingshetty, L., Cameron, N. J., Mclernon, D. J. & Bhattacharya, S. Predictors of success after in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 121, 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2024.03.003 (2024).

Ratna, M. B., Bhattacharya, S., Abdulrahim, B. & McLernon, D. J. A systematic review of the quality of clinical prediction models in in vitro fertilisation. Hum. Reprod. 35, 100–116. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez258 (2020).

Jones, C. A. et al. Prediction of individual probabilities of livebirth and multiple birth events following in vitro fertilization (IVF): a new outcomes counselling tool for IVF providers and patients using HFEA metrics. J. Exp. Clin. Assist. Reprod. 8, 3 (2011).

Luke, B. et al. A prediction model for live birth and multiple births within the first three cycles of assisted reproductive technology. Fertil. Steril. 102, 744–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.020 (2014).

Vaegter, K. K. et al. Which factors are most predictive for live birth after in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) treatments? Analysis of 100 prospectively recorded variables in 8,400 IVF/ICSI single-embryo transfers. Fertil. Steril. 107, 641-648.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.12.005 (2017).

Dhillon, R. K. et al. Predicting the chance of live birth for women undergoing IVF: a novel pretreatment counselling tool. Hum. Reprod. 31, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev268 (2016).

Sufriyana, H. et al. Comparison of multivariable logistic regression and other machine learning algorithms for prognostic prediction studies in pregnancy care: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 8, e16503. https://doi.org/10.2196/16503 (2020).

Meijerink, A. M. et al. Prediction model for live birth in ICSI using testicular extracted sperm. Hum. Reprod. 31, 1942–1951. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew146 (2016).

Sun, B. et al. Prediction of sepsis among patients with major trauma using artificial intelligence: a multicenter validated cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 10, 1097. https://doi.org/10.1097/JS9.0000000000001866 (2024).

Kuo, C. Y., Kuo, L. J. & Lin, Y. K. Artificial intelligence based system for predicting permanent stoma after sphincter saving operations. Sci. Rep. 13, 16039. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43211-w (2023).

Silva, G. F. S., Fagundes, T. P., Teixeira, B. C. & Chiavegatto Filho, A. D. P. Machine learning for hypertension prediction: a systematic review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 24, 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-022-01212-6 (2022).

Collins, G. S. et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 385, e078378. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078378 (2024).

Bacon, A. M. & The Long, V. The first discovery of a complete skeleton of a fossil orang-utan in a cave of the Hoa Binh Province, Vietnam. J. Hum. Evol. 41, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhev.2001.0496 (2001).

Yang, I. J. et al. Usage and cost-effectiveness of elective oocyte freezing: a retrospective observational study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 20, 123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-022-00996-1 (2022).

Steyerberg, E. W. Validation in prediction research: the waste by data splitting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 103, 131–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.07.010 (2018).

Pencina, M. J. & D’Agostino, R. B. Sr. Evaluating discrimination of risk prediction models: the C statistic. JAMA 314, 1063–1064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.11082 (2015).

Rufibach, K. Use of Brier score to assess binary predictions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 938–939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.009 (2010).

Crawford, N. M. & Steiner, A. Z. Age-related infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 42, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2014.09.005 (2015).

Fleming, R. & Jenkins, J. The source and implications of progesterone rise during the follicular phase of assisted reproduction cycles. Reprod. Biomed. Online 214, 446–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.05.018 (2010).

Karatasiou, G. I. et al. Is the probability of pregnancy after ovarian stimulation for IVF associated with serum estradiol levels on the day of triggering final oocyte maturation with hCG? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37, 1531–1541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-020-01829-z (2020).

Chen, H., Cai, J., Liu, L. & Sun, X. Roles of estradiol levels on the day of human chorionic gonadotrophin administration in the live birth of patients with frozen embryo transfer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 34, e23422. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23422 (2020).

Goldman, R. H. et al. Association between serum estradiol level on day of progesterone start and outcomes from frozen blastocyst transfer cycles utilizing oral estradiol. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 39, 1611–1618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-022-02521-0 (2022).

Porcu, G., Lehert, P., Colella, C. & Giorgetti, C. Predicting live birth chances for women with multiple consecutive failing IVF cycles: a simple and accurate prediction for routine medical practice. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7827-11-1 (2013).

Zieliński, K. et al. Personalized prediction of the secondary oocytes number after ovarian stimulation: A machine learning model based on clinical and genetic data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011020 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Yunnan Revitalization Talent Support Program (XDYC-MY-2022-0057), Academic Leader of Talent Echelon Construction of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (RCTDXS-202304), the First-Class Discipline Team of Kunming Medical University (2024XKTDTS16), and the Kunming Medical University Young and Middle-aged Discipline Leaders and Reserve Candidates Talent Cultivation Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY and XYY conceptualized the study. ZYY, HZJ, TX and LXY extracted and cleaned data. PJW and GXYJ performed data analysis and visualization. PJW and GXYJ prepared the draft manuscript. LY and XYY critically revised the manuscript. All authors had read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, J., Geng, X., Zhao, Y. et al. Machine learning algorithms in constructing prediction models for assisted reproductive technology (ART) related live birth outcomes. Sci Rep 14, 32083 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83781-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83781-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Machine-learning estimation of live birth after AIH-based intrauterine insemination and its association with the number of inseminations per cycle

Middle East Fertility Society Journal (2025)