Abstract

Despite previous studies supporting a close relationship between constipation and chronic kidney disease (CKD), the potential impact of constipation on incident CKD and the role of laxatives remains uncertain. We analyzed longitudinal data from the UK Biobank, which links baseline assessment data with follow-up data from hospital episode statistics and general practice records. Constipation was defined with diagnostic codes or regular use of laxatives at baseline as reported in the questionnaire. Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the association between constipation and incident CKD. After excluding individuals with pre-existing CKD or missing covariates, 118,020 participants with general practice follow-up data were included in the main analysis. Over a median follow-up of 7.4 years, 6,833 (5.8%) patients developed CKD. Constipation was significantly associated with increased risk of CKD development in the multivariable adjusted models (hazard ratio [HR] 1.51, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.37–1.67) for ICD-defined constipation, HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.23–1.47 for constipation defined by ICD codes or laxative use). Patients with ICD-defined constipation, even when taking laxatives, were found to have a higher risk of incident CKD than those without constipation (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.08–1.85). We found no moderating effects of laxative use on the association between constipation and incident CKD. Constipation is independently associated with incident CKD in the large population-based longitudinal cohort. These findings highlight constipation as a potential risk factor or predictor of CKD development. Further research is warranted to elucidate the role of laxatives in controlled study designs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects more than 800 million individuals worldwide, contributing to 1.2 million deaths annually1. The rapidly increasing prevalence of CKD, driven by the aging population and the growing burden of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, is a major threat to public health2. However, despite recent advances in new drugs, such as sodium-glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, care for patients with CKD remains insufficient.

CKD is defined as persistent functional or structural damage to the kidney itself; however, it involves multiple organ relationships and presents with numerous extrarenal symptoms3. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation, are particularly common in the CKD population4. Although constipation, manifested as infrequent bowel movements and hard stools, may be considered self-limiting and benign, it has a significant impact on health outcomes. Constipation severely impairs health-related quality of life and is associated with cardiovascular events and mortality5,6,7,8. In particular, growing evidence has shed light on the association between constipation and CKD.

The prevalence of constipation has been reported to increase markedly with higher stages of CKD, reaching over 40% in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)9,10. While factors such as fluid restriction, polypharmacy, and low physical activity contribute to this high prevalence, some evidence indicates that constipation can adversely affect kidney outcomes11,12. Chronic constipation and reduced gut motility are linked to chanages in gut microbiota13,14. Therefore, the association between constipation and CKD is mechanistically mediated by the gut-kidney axis, which involves gut-derived uremic toxins and an impaired intestinal barrier9. Nevertheless, studies linking constipation to the risk of CKD remain scarce, and the role of laxatives in this relationship remains unclear. Herein, we aimed to investigate the longitudinal association between constipation and incident CKD and to evaluate the effect of laxatives on the association using a large-scale population-based cohort.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was conducted using data from the UK Biobank, a large-scale population-based cohort encompassing a variety of biomedical data including sociodemographic, genetic, biochemical, and imaging data15. Approximately 500,000 participants aged between 40 and 69 years were recruited at 22 assessment centers across the United Kingdom between 2006 and 2010 16. All participants provided informed consent and underwent self-reported touchscreen questionnaires, verbal interviews, physical measurements, and biological sample collection during the initial assessment visit. Biological samples, including blood and urine, were minimally processed at assessment centers and transported to central facilities for storage at -80 °C or in liquid nitrogen17. Sample measurements were performed in a central laboratory using automated instruments. We included participants who completed the UK Biobank initial assessment. The exclusion criteria were: (1) missing self-reported laxative use data at baseline; (2) pre-existing CKD at baseline; and (3) missing relevant covariates required for the analysis. The index date for the cohort was defined as the date of the initial assessment visit. Therefore, pre-existing CKD was defined as the presence of ICD-10 or OPCS4 codes for CKD prior to the index date or based on test results conducted on samples collected at the initial assessment, including an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m² or a urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) > 30 mg/g. A detailed flow diagram of participant selection is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. GP data were available for only approximately 48% of participants, whereas HES data covered all biobank participants. Therefore, we performed the analysis separately for the two cohorts: all individuals (HES cohort) and those with GP data (GP cohort). Finally, we included 273,333 individuals in the HES cohort and 118,020 in GP cohort, respectively. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as part of the UK Biobank project (ID 77605) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (IRB No. 2021-09-022).

Exposure assessment

Constipation was identified by two different definitions: (1) presence of ICD-10 code K59.0 or ICD-9 code 5640 in any GP or HES data (ICD-defined constipation) and (2) definition 1 plus self-reported regular use of laxatives for constipation in a touchscreen questionnaire (Data-Field 6154), indicating use of laxatives on most days of the week for the last 4 weeks. Laxatives were classified into four types (stool softeners, bulk-forming agents, stimulants, and osmotic laxatives) according to the records of self-reported medication records (Data-Field 20003)18.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was incident CKD as ascertained from the GP, HES, and death data (Supplemental Table 1). Incident CKD was defined based on ICD-10 codes (E10.2, E11.2, E13.2, I12.x, I13.x, N18.x, T86.1 and Z94.0) and OPCS4 codes (L74.1-74.6, L74.8-74.9, M01.2-01.9, M02.3, M08.4, M17.2, M17.4, M17.8-17.9, X40.2, X40.5-40.6, and X41.1-41.2). Study participants were followed up from baseline assessment until the date of incident CKD, death, loss to follow-up, and the censoring date of data sources, whichever occurred first. The censoring dates from the GP and HES data were used for the GP and HES cohorts, respectively. The censoring dates for the different data sources are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Covariates assessment

Baseline covariates were selected for multivariable-adjusted models, including sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, medical conditions, medication use, and biochemical tests. Socioeconomic status was measured by Townsend deprivation index and categorized into three groups: low (≥ 80th percentile), intermediate (20-80th percentile), and high (< 20th percentile). Education level was categorized as university degree or higher versus not. Healthy diet was defined as meeting dietary recommendations for cardiometabolic health in at least 4 of 7 food groups (fruits, vegetables, fish, processed meat, unprocessed red meats, whole grains, refined grains)19,20. Physical activity was categorized into low, moderate, and high levels based on activity patterns and total amount as defined by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire21. Hypertension was defined as antihypertensive medication use, diagnosis of hypertension by a physician, occurrence of ICD-10 codes for hypertension before recruitment, and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg at baseline. Diabetes was defined as diabetes medication use, diagnosis of diabetes by a physician, occurrence of ICD-10 codes for diabetes before recruitment, and fasting blood glucose of ≥ 126 mg/dl or HbA1c of ≥ 6.5% at baseline. Self-reported medication uses were identified for anticholinergics, renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors, opioids, statins, anti-diarrheal drugs, and diuretics after mapping drug codes of the UK Biobank to active ingredients22. Anticholinergic drugs were selected according to the anticholinergic risk scales23. Estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) Equation24. Urine albumin levels below the detection limit of assay were set to 6.7 mg/L, which was used to calculate urinary albumin- creatinine ratio25,26. More detailed descriptions of the included covariates are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of the study participants were compared with the standardized mean difference according to the presence or absence of constipation. Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the association between constipation and incident CKD, with follow-up time as the timescale. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the scaled Schoenfeld residuals. We also examined the joint associations between constipation diagnosis, laxative use, and incident CKD by comparing the four groups based on laxative use and constipation. Subgroup analyses were conducted and stratified by sex, age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, and laxative use. Additionally, several sensitivity analyses were performed. First, a competing risk analysis was conducted using the Fine and Grey subdistribution hazard model, considering death as a competing event. Second, multiple imputation by chained equations was performed to address missing covariates without excluding cases with missing values. Third, participants with outcomes within 3 years from baseline were excluded to avoid possible reverse causation. Fourth, ICD code-based constipation was more strictly defined as multiple occurrences of the codes. Fifth, we considered constipation as having at least one ICD code for constipation within 3 years before the baseline to exclude old transient episodes. In addition, to assess residual confounding bias, we tested hip fracture as a negative control outcome in a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for the covariates used in the main analysis27,28. Hip fracture was defined based on the OCD-10 codes (S72.0, S72.1, and S72.2) and ICD-9 code (820) recorded in the HES data. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of participants according to the presence or absence of constipation are shown in Table 1 (GP cohort) and Supplementary Table 3 (HES cohort). Individuals with constipation accounted for 4,780 (4.1%, ICD-based definition) and 7,076 (6.0%, ICD-defined constipation or regular laxative use at baseline) in the GP cohort and 5,958 (2.2%, ICD-based definition) and 11,988 (4.4%, ICD-defined constipation or regular laxative use at baseline) in the HES cohort. In the GP cohort of 118,020 participants, 51.2% were female, 5.2% had diabetes, and 45% had hypertension at baseline. The mean age and eGFR were 55.5 years and 92.3 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Individuals with constipation are more likely to be female, older, and use anticholinergics and opioids. These characteristics were similar to those observed in the HES cohort.

Association between constipation and incident CKD

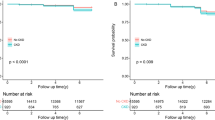

The associations between constipation and incident CKD according to the definition of constipation are shown in Table 2 (GP cohort) and Supplementary Table 4 (HES cohort). In the GP cohort, during a median follow-up of 7.4 years, incident CKD occurred in 6,833 individuals (5.8%). Cumulative incidence plots for incident CKD according to the definition of constipation were given in Fig. 1 (GP cohort) and Supplementary Fig. 2 (HES cohort). ICD-defined constipation at baseline is independently associated with incident CKD from the unadjusted model (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.42–1.74) to the fully-adjusted model (HR 1.51, 95% CI 1.37–1.67). When using the definition combined with laxative use, the associations was slightly attenuated, but remained significant (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.23–1.47 in the fully adjusted model). In the HES cohort, CKD occurred in 8,287 individuals (3.0%) during a median follow-up of 13.7 years. The HES cohort also found that individuals with constipation had a significantly higher risk of incident CKD compared to those without constipation regardless of constipation definition (ICD-defined constipation, HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.09–1.40; ICD-defined constipation or regular laxative use at baseline, HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.07–1.28 in the fully adjusted models). Overall, the estimated HRs in the HES cohort were lower than those in the GP cohort.

Joint association between constipation and laxative use

We further assessed the joint association between constipation, laxative use, and incident CKD. In the GP cohort, the ICD-defined constipation group, regardless of laxative use, was associated with a higher risk of incident CKD compared to the reference group (those without both constipation and laxative use) (Table 3). The HR of constipated individuals without laxative use was the highest among the four groups (HR 1.53, 95% CI 1.37–1.70). Even with laxative use, those with ICD-defined constipation remained at an increased risk of developing CKD (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.08–1.85). We noted no difference in the risk of incident CKD between laxative and non-laxative users among those without constipation. When self-reported laxative use was included in the definition of constipation, the HR for patients with constipation using laxatives was not significant (HR, 1.10, 95% CI 0.95–1.27). Similar findings were observed in the HES cohort; however, the overall HRs were lower than those in the GP cohort (Supplementary Table 5). We also examined the association between the different laxative types and incident CKD in individuals with constipation (Supplementary Table 6). Overall, no significant protective effect against incident CKD was found with the use of any type of laxative, except for unspecified laxative use in the GP cohort. Rather, individuals who used stool softeners showed a higher risk than non-laxative users.

Subgroup analysis and negative control outcome analysis

We stratified the study population according to the sex, age, BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25), diabetes, and laxative use (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Most subgroups revealed findings consistent with those of the main analysis. There were no significant interactions between the stratified factors, except for BMI in the HES cohort. Negative control outcome analyses were also performed for hip fractures by adjusting for the covariates used in the main analysis (Supplementary Table 7). We found no significant associations between constipation and hip fractures after adjusting for lifestyle, health status, medication use, and biochemical parameters (Models 3 and 4), indicating that our findings are unlikely to be the result of residual confounding.

Sensitivity analyses

In the competing risk analysis, the subdistribution hazard ratio (SHR) for incident CKD was similar to the HRs in the main analysis (Supplementary Table 8). Pooled analyses using multiple imputed datasets did not alter the main findings (Supplementary Table 9). When individuals whose outcomes occurred within the first 3 years of follow-up were excluded from the analysis, the association between constipation and incident CKD remained significant (Supplementary Table 10). Constipation defined by multiple code occurrences also exhibited an independent association overall (Supplementary Table 11). Lastly, when including individuals with at least one ICD code occurrence within the last 3 years before baseline, the main results remained significant (Supplementary Table 12).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a longitudianl association between constipation and incident CKD using data from a large biobank and linked medical records. Constipation was independently associated with CKD occurrence regardless of laxative use. We obtained consistent results with different definitions of constipation and follow-up data, and the sensitivity analyses further supported our findings.

The close relationship between constipation and CKD has been widely recognized in previous clinical observations. Constipation is highly prevalent in patients with CKD, particularly in advanced stages, and laxatives are among the most commonly prescribed medications in the CKD population. The current evidence suggests a bidirectional association between constipation and CKD. Lifestyle factors in patients with CKD, including low fiber intake, physical inactivity, and fluid restriction, can lead to constipation. Medications frequently used in patients with CKD, such as oral iron supplements, phosphorus binders, and diuretics, are potential contributors to constipation10. Conversely, constipation itself may serve as an independent risk factor or predictor of CKD. To date, there have been limited studies examining the longitudinal association between constipation and incident CKD or CKD progression. Sumida et al. first reported the independent association between constipation and incident CKD using data from the US Veterans Affairs medical care facilities12. In their analysis, patients with constipation exhibited a significantly higher risk of incident CKD and a rapid decline in eGFR compared to those without constipation. Lu et al. investigated the association between constipation and ESKD development in CKD patients using nationwide health insurance claims data in Taiwan11. They found that patients with constipation within 1 year before baseline revealed a HR of 1.9 for ESKD compared to those without. Despite these encouraging findings, these studies were limited in terms of data sources and demographic constraints of the participants. Most of the covariates used were ascertained from prescription and diagnosis codes; thus, covariates such as biochemical test results and lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity were not available. However, the sociodemographic and biochemical data provided by the UK Biobank were subjected to a high level of quality control, and health outcomes were obtained from reliable data sources. As a result, we provide robust evidence for the association between constipation and CKD found in previous studies. Our findings revealed an independent association between constipation and incident CKD in both the GP and HES cohorts, with a stronger association observed in the GP cohort. This may reflect that constipation is predominantly diagnosed in outpatient settings and constipation identified during hospitalization could result from transient conditions caused by acute illness29.

The biological link between constipation and CKD may be mediated by gut dysbiosis. The gut microbiota plays a key role in regulating intestinal motility30,31. In particular, constipation in CKD is likely attributed to slow transit time based on human and preclinical data32,33,34. Prolonged colonic retention of stool induces the dominance of protein fermentation, which is responsible for gut-derived uremic toxins35,36. These gut-derived metabolites, including p-cresol sulfate, indoxyl sulfate, and trimethylamine N-oxide, were shown to induce kidney fibrosis in animal models37,38,39. Experimental studies have shown that modulating the gut microbiome with probiotic supplements or laxatives can ameliorate kidney fibrosis40,41,42,43; however, the causal role of constipation in CKD is still unclear, and our findings do not imply a direct causal relationship between the two. Gut microbiota changes are observed even in early-stage CKD (e.g. eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2), preceding typical kidney injury markers such as proteinuria44,45. Thus, constipation before CKD diagnosis may reflect subclinical CKD-related gut dysbiosis.

On the other hand, although laxatives are prescribed more often to individuals with CKD, the exact impact or role of laxative use on kidney outcome remains unclear10. Laxatives are a class of drugs that strongly interact with the gut microbiome, possibly affecting host health46,47. In our study, the HR for incident CKD was slightly higher in the non-laxative user group than in the laxative user group; however, no interaction was found between constipation and laxative use. Due to the observational nature of the study, laxative use may reflect both pharmacological intervention and constipation severity. Despite the risk of dehydration and kidney function impairment from laxative overuse, we found no difference in the risk between laxative and non-laxative users without a constipation diagnosis48. Individuals with ICD-defined constipation likely have severe symptoms unresponsive to over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. Those with ICD-defined constipation who did not use laxatives had the highest HR for incident CKD, which can be speculated as not being effectively managed, despite severe symptoms. Interestingly, we observed a higher risk of incident CKD with stool softeners. This finding may be related to concerns about the ineffectiveness of stool softener docusate as a first-line laxative49,50. Based on our findings, we cannot conclude that laxatives have no role in preventing CKD development. Still, there is some evidence supporting the beneficial effects of laxatives. Lubiprostone and linaclotide have demonstrated protective effects against kidney fibrosis and inflammation in a mouse model of adenine-induced CKD by modulating the gut microbiota and uremic toxin levels42,43. To accurately determine the effect of laxatives on kidney function, a more elaborate study design in human subjects (possibly clinical trials) is required. Nevertheless, the method used to define regular laxative use was one of the strengths of this study. The UK Biobank questionnaire was able to capture OTC laxatives that did not require a prescription and was assessed for most participants. In addition, the definition based on regular use for 4 weeks or more is more suitable for assessing the impact of chronic laxative use.

This study has some limitations. First, this was an observational study; thus, causal associations could not be concluded. Second, the UK biobank cohort predominantly consists of white and relatively healthy participants, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Third, laxative use was assessed only at baseline, not throughout the follow-up. Fourth, the severity of constipation was not determined, which may have led to bias in the analysis. Fifth, our analysis by laxative type was limited due to unspecified drug names from some laxative users. Given that each laxative has a unique mechanism of action, further investigations into their specific effects on kidney outcomes are warranted. Finally, we performed multivariable-adjusted analysis; however, residual confounding factors may remain. Despite the lack of statistical significance in the negative control outcome analysis, the comparable effect sizes observed in the HES cohorts across different outcomes indicate that the estimates should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, our study newly adds the longitudinal evidence of the gut-kidney axis in relation to constipation and incident CKD using large biobank data. This finding underscores the importance of recognizing constipation not only as a burdensome symptom but also as a potential predictor of CKD development.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our prospective analysis of the UK Biobank cohort demonstrated a significant association between constipation and incident CKD. This association remained significant even among individuals with regular laxative use at baseline. Further controlled studies are required to evaluate the exact effects of laxatives on kidney outcomes in individuals with constipation.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the published article and Supplementary Information file. The raw data supporting the results of this study are available from the UK Biobank. UK Biobank data is only available to approved researchers. To access data, researchers need to submit an application to the UK Biobank Access Management System and be approved. Further information on data access is provided at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk.

Change history

21 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90553-8

References

Kovesdy, C. P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl () 12, 7–11, doi: (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kisu.2021.11.003 (2022).

Francis, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6 (2024).

Zoccali, C. et al. The systemic nature of CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.52 (2017).

Biruete, A., Shin, A., Kistler, B. M. & Moe, S. M. Feeling gutted in chronic kidney disease (CKD): gastrointestinal disorders and therapies to improve gastrointestinal health in individuals CKD, including those undergoing dialysis. Semin Dial. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.13030 (2021).

Sumida, K. et al. Constipation and risk of death and cardiovascular events. Atherosclerosis 281, 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.12.021 (2019).

Honkura, K. et al. Defecation frequency and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japan: the Ohsaki cohort study. Atherosclerosis 246, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.007 (2016).

Salmoirago-Blotcher, E., Crawford, S., Jackson, E., Ockene, J. & Ockene, I. Constipation and risk of cardiovascular disease among postmenopausal women. Am. J. Med. 124, 714–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.03.026 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Health-related quality of life in dialysis patients with constipation: a cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 7, 589–594. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S45471 (2013).

Sumida, K., Yamagata, K. & Kovesdy, C. P. Constipation in CKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 5, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2019.11.002 (2020).

Kim, K. et al. Real-world evidence of constipation and laxative use in the Korean population with chronic kidney disease from a common data model. Sci. Rep. 14, 6610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57382-7 (2024).

Lu, C. Y., Chen, Y. C., Lu, Y. W., Muo, C. H. & Chang, R. E. Association of Constipation with risk of end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 20, 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-019-1481-0 (2019).

Sumida, K. et al. Constipation and Incident CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1248–1258. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016060656 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Characteristics of the gut microbiome and serum metabolome in patients with functional constipation. Nutrients 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071779 (2023).

Parthasarathy, G. et al. Relationship between microbiota of the Colonic Mucosa vs feces and symptoms, Colonic Transit, and methane production in female patients with chronic constipation. Gastroenterology 150 (e361), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.005 (2016).

Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z (2018).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 12, e1001779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 (2015).

Elliott, P., Peakman, T. C. & Biobank, U. K. The UK Biobank sample handling and storage protocol for the collection, processing and archiving of human blood and urine. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37, 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dym276 (2008).

Feng, J. et al. Association of laxatives use with incident dementia and modifying effect of genetic susceptibility: a population-based cohort study with propensity score matching. BMC Geriatr. 23, 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03854-w (2023).

Mozaffarian, D. Dietary and Policy priorities for Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetes, and obesity. Circulation 133, 187–225. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018585 (2016).

Said, M. A., Verweij, N. & van der Harst, P. Associations of Combined Genetic and Lifestyle Risks With Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes in the UK Biobank Study. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1717 (2018).

Lee, P. H., Macfarlane, D. J., Lam, T. H. & Stewart, S. M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 8, 115. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 (2011).

Wu, Y. et al. Genome-wide association study of medication-use and associated disease in the UK Biobank. Nat. Commun. 10, 1891. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09572-5 (2019).

Duran, C. E., Azermai, M. & Vander Stichele, R. H. Systematic review of anticholinergic risk scales in older adults. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 69, 1485–1496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1499-3 (2013).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Haas, M. E. et al. Genetic Association of Albuminuria with Cardiometabolic Disease and Blood pressure. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.004 (2018).

Sukcharoen, K. et al. IgA Nephropathy genetic risk score to Estimate the Prevalence of IgA Nephropathy in UK Biobank. Kidney Int. Rep. 5, 1643–1650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2020.07.012 (2020).

Haring, B. et al. Laxative use and incident falls, fractures and change in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the women’s Health Initiative. BMC Geriatr. 13, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-38 (2013).

Rapp, K. et al. Epidemiology of hip fractures: systematic literature review of German data and an overview of the international literature. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 52, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-018-1382-z (2019).

Martin, B. C., Barghout, V. & Cerulli, A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manag Care Interface. 19, 43–49 (2006).

Vicentini, F. A. et al. New concepts of the interplay between the gut microbiota and the enteric nervous system in the Control of Motility. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1383, 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05843-1_6 (2022).

Waclawikova, B., Codutti, A., Alim, K. & El Aidy, S. Gut microbiota-motility interregulation: insights from in vivo, ex vivo and in silico studies. Gut Microbes. 14, 1997296. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2021.1997296 (2022).

Wu, M. J. et al. Colonic transit time in long-term dialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 44, 322–327. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.04.048 (2004).

Nishiyama, K. et al. Chronic kidney disease after 5/6 nephrectomy disturbs the intestinal microbiota and alters intestinal motility. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 6667–6678. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.27408 (2019).

Yu, C. et al. Chronic kidney Disease elicits an intestinal inflammation resulting in Intestinal Dysmotility Associated with the activation of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthesis in rat. Digestion 97, 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481618 (2018).

Macfarlane, G. T., Cummings, J. H., Macfarlane, S. & Gibson, G. R. Influence of retention time on degradation of pancreatic enzymes by human colonic bacteria grown in a 3-stage continuous culture system. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 67, 520–527 (1989).

Roager, H. M. et al. Colonic transit time is related to bacterial metabolism and mucosal turnover in the gut. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16093. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.93 (2016).

Watanabe, H. et al. p-Cresyl sulfate causes renal tubular cell damage by inducing oxidative stress by activation of NADPH oxidase. Kidney Int. 83, 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2012.448 (2013).

Miyazaki, T. et al. Indoxyl sulfate stimulates renal synthesis of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and progression of renal failure. Kidney Int. Suppl. 63, S211–214 (1997).

Tang, W. H. et al. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 116, 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305360 (2015).

Li, F., Wang, M., Wang, J., Li, R. & Zhang, Y. Alterations to the gut microbiota and their correlation with inflammatory factors in chronic kidney disease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 206. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00206 (2019).

Huang, H., Li, K., Lee, Y. & Chen, M. Preventive effects of Lactobacillus mixture against chronic kidney disease progression through Enhancement of Beneficial Bacteria and downregulation of gut-derived uremic toxins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 7353–7366. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01547 (2021).

Nanto-Hara, F. et al. The guanylate cyclase C agonist linaclotide ameliorates the gut-cardio-renal axis in an adenine-induced mouse model of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 35, 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz126 (2020).

Mishima, E. et al. Alteration of the intestinal environment by Lubiprostone Is Associated with Amelioration of Adenine-Induced CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1787–1794. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2014060530 (2015).

Wu, I. W. et al. Gut microbiota as diagnostic tools for mirroring Disease Progression and circulating nephrotoxin levels in chronic kidney disease: Discovery and Validation Study. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 420–434. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.37421 (2020).

Wu, I. W. et al. Integrative metagenomic and metabolomic analyses reveal severity-specific signatures of gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Theranostics 10, 5398–5411. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.41725 (2020).

Vich Vila, A. et al. Impact of commonly used drugs on the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 11, 362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14177-z (2020).

Tropini, C. et al. Transient Osmotic Perturbation Causes Long-Term Alteration to the Gut Microbiota. Cell 173, 1742–1754 e1717, doi: (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.008

Copeland, P. M. Renal failure associated with laxative abuse. Psychother. Psychosom. 62, 200–202. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288923 (1994).

Hurdon, V., Viola, R. & Schroder, C. How useful is docusate in patients at risk for constipation? A systematic review of the evidence in the chronically ill. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 19, 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00157-8 (2000).

Fakheri, R. J. & Volpicelli, F. M. Things we do for no reason: prescribing Docusate for Constipation in hospitalized adults. J. Hosp. Med. 14, 110–113. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3124 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the UK Biobank participants and management team. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 77605.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K.: Formal analysis, original draft, editing. W-H.C.: Formal analysis and review. S.D.H.: Investigation and review. S.W.L.: Investigation. J.H.S.: Supervision, conceptualization. All the authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Acknowledgements section was incorrect. “None.” now reads: “We sincerely thank the UK Biobank participants and management team. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application number 77605."

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K., Cho, WH., Hwang, S.D. et al. Association between constipation and incident chronic kidney disease in the UK Biobank study. Sci Rep 14, 32106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83855-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83855-w

This article is cited by

-

A guide to uraemic toxicity

Nature Reviews Nephrology (2025)