Abstract

Worldwide, anemia in under-five children is a serious public health problem that causes significant morbidity and mortality. It also negatively impacts children’s physical growth, focus, memory, and academic performance. Despite this, there is a paucity of up-to-date information on the spatial distribution and determinants of under-five anemia in Mozambique. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the spatial variation and determinates of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique by using the most recent demographic and health survey data. A cross-sectional study was conducted using the most recent demographic and health survey data of Mozambique. A total weighted sample of 3127 under-five children was included in the study. Spatial SaTScan statistics were done using Kuldroff’s SaTScan version 9.6 software. ArcGIS version 10.7 software is used to visualize the spatial distribution of under-five anemia. A multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analysis was employed to identify the determinants of under-five anemia. The level of statistical significance was declared at a p-value of < 0.05. Overall, the prevalence of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique was 49.46% (95% CI 47.70–51.21). Under-five anemia was not evenly distributed across the country; a higher distribution was observed in Zambezia, Nampula, Safala, and the southern part of Gaza; fewer cold spots were observed in the western and southern parts of Niassa, the eastern part of Tete, the western part of Manica, and Maputo City. In spatial scan statistics, children in the most likely cluster were 1.58 times more likely to be anemic than those living outside the window (RR = 1.58, P-value < 0.001). Children with fathers with no formal education, children from anemic mothers, children whose mothers are underweight, children residing in the Zambzia region, children residing in the Nampula region, and children residing in the Niassa region were significantly associated with under-five anemia in Mozambique. The burden of under-five anemia in Mozambique is higher and distributed non-randomly across regions. Maternal anemia, underweighted mothers, husband education, and regions in Mozambique were found to be significant determinants of anemia in under-five children. Improving the nutritional status of mothers and interventions to address maternal anemia, with special attention to the Nampula and Zambzia regions, are recommended to reduce under-five anemia in Mozambique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anemia is a condition characterized by a reduced quantity of red blood cells, or hemoglobin, which transport oxygen to bodily tissues1. A hemoglobin content of less than 11 g/dl is considered anemia by the World Health Organization (WHO) in children under the age of five years2. Anemia is classified as a severe public health concern when the prevalence is 40% or more, a moderate public health problem when the prevalence is between 20 and 40%, and a mild public health problem when the prevalence is between 5 and 20 in any group3. Children are especially vulnerable to anemia at this key phase of their development4. Iron deficiency is the leading cause of anemia in children under the age of five, with a lower proportion related to other micronutrient deficiencies such as folate, Vitamin A, and B125,6.

Worldwide, anemia in children under-five is a serious public health issue. According to statistics from the World Health Organization, 40% of children under the age of five were anemic7,8. In 2019, the global anemia prevalence was 39.8% among under-five children. Even though the global burden of anemia among children under-five has slowly decreased over the years, from 48.0 to 39.8%, since 2010, it has been unchanged then after9. The prevalence varies across countries, with the highest percent observed in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and South Asia10.Particularly, the highest records notably observed in the African region (60.2%)6.

Anemia has a significant impact on socioeconomic development and is a key indicator of poor nutrition and health. Anemia negatively impacts children’s physical growth, focus, memory, development, cognition, learning, immunity, and academic performance11,12. In addition, childhood anemia is associated with a decreased ability to fight infections that predispose them to significant morbidity and mortality16.

Anemia has multiple causes, with infectious illness and nutritional deficiency being the primary causes in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA)13,14. According to earlier research, various variables contribute to the development of anemia among under-five children. Inadequate iron and vitamin A intake, increased vulnerability to infection, socio-demographic characteristics of households, including region, mother’s working status, wealth index, water source, maternal anima status, and child characteristics such as child age, birth order, nutritional status, and birth size, were significant determinants of anemia among children under-five15,16,17,18,19,20,21. But the geographic disparity across the country regions was not explored yet.

Sub-Saharan countries continue to suffer a high rate of under-five mortality despite notable worldwide improvements in the socioeconomic and health status of communities22. About 67.6% of under-five children in Africa suffer from anemia, which is responsible for 15–18% of under-five mortality22,23. To achieve the targets of reducing child mortality of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-2030, it is necessary to generate adequate evidence on the burden of anemia and its determinants, which is highly crucial for the development of timely interventions in anemia prevention and treatment. Despite this, there is a paucity of up-to-date information on the spatial distribution and factors associated with anemia in Mozambique. Thus, identifying geographically risky areas or hotspot areas of under-five anemia helps government authorities and implementers prioritize intervention against under-five anemia. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the spatial variation and determinates of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique by using the most recent demographic and health survey data.

Method

Study setting

Mozambique, located in south-eastern Africa with geographic coordinates of 18° 15’ South and 35° 00’ East, has an estimated population of around 34 million inhabitants, the majority of whom live in rural areas24,25,26. Its borders are the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Africa to the south-west. The country had eight regions, including the capital city (Maputo). The regions were Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Nampula, Zambzia, Tete, Manica, Sofala, Inhambane, Gaza, Maputo, and Cidade de Maputo27.

Data source and sampling procedure

The dataset used in this analysis comes from the Mozambique 2023 Demographic and Health Survey data (DHS), retrieved from the MEASURE DHS public repository. This study used the most recent DHS data set. Every five years, nationwide surveys known as the DHS are conducted worldwide in low- and middle-income nations. Data were collected from a national representative sample of approximately 14,250 households from all 11 regions in Mozambique. The sampling procedure used in the 2023 Mozambique demographic and health survey (MDHS) was stratified two-stage cluster sampling, designed to yield representative results at the national level in urban and rural areas and for most DHS indicators in each country’s region.

In the first stage, 619 targeted clusters were selected from the sampling frame using a probability-proportional to-size strategy for urban and rural areas in each region. Then the number of targeted clusters was selected with equal probability through systematic random sampling of the clusters selected in the first phase for urban and rural areas.

During the second stage a household listing and map updating in all selected clusters to create a list of households for each cluster. The list served as a sampling frame for the household sample. A fixed number of 30 households in each cluster were randomly selected from the list for interviews. Thus, 14,250 households were successfully interviewed in 619 clusters. Of the households interviewed, 7,123 women ages 15–49 and 7,127 men ages 15–59 completed individual interviews. For this study, women with a birth history who had given birth five years before the surveys were included. This study included a weighted sample of 3,127 kids between the ages of 6 and 59 months for analysis. Only the last births of women aged 15–49 years preceding the survey were included in the study.

Inclusion criteria

All children aged 6–59 months preceding the survey years in the selected enumeration areas (EAs) who were in the study area were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Children in the age category of 6–59 months, which is not assessed for anemia based on DHS guidelines and has a missing value for the outcome variables, were excluded.

Study population

The study population consisted of children aged 6–59 months preceding the five-year survey period in the selected enumeration areas, which are the primary sampling units of the survey cluster. The mother or caregiver was interviewed for the survey in the country, and mothers who had more than one child during the survey period were asked about the most recent child.

Study variables

Outcome of variable

The outcome variable is anemia among under-five children. According to the WHO criteria, children aged 6–59 months are considered anemic if their hemoglobin is less than 11 g/dl. The outcome was coded as “Yes = 1” for anemic children and “No = 0” for non-anemic children.

Independent variables

Both individual and community-level factors were reviewed from different literatures, and these include child age, maternal education, mother working status, educational status, husband education, antenatal care visit (ANC), media exposure, iron supplementation, place of delivery, number of household members and under-five children, diarrhea in the past two weeks, wealth index, birth order, postnatal care (PNC), and source of drinking water16,28,29,30,31,32,33. Whereas, residence, region, community women’s illiteracy level, community poverty level, and community media exposure were community-level variables aggregated from individual-level factors34,35,36,37.

Community level variables

Community-level women’s illiteracy and community-level poverty were aggregated from individual women’s characteristics of education and wealth index, respectively. Since the aggregate values for all generated variables have no meaning at the individual level, they were categorized into groups based on median values. Median values were used to categorize as high and low because all aggregated variables were not normally distributed. Similar procedures were applied to all aggregate variables.

Data management

The data were checked for completeness and weighted before being used for statistical analysis. The analysis was done using STATA version 17. Due to the non-proportional allocation of the sample to different regions, urban and rural areas, and the possible difference in response rate, proportion, and frequencies were estimated after applying sample weights to the data to account for disproportionate sampling and non-response recommended by DHS. A detailed explanation of the weighting procedure can be found in the in the DHS portal at https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/Analyzing_DHS_Data.htm38. Figures were generated by ArcGIS version 10.7 software. We used the Mozambique regional shape file to show the hotspot area, kriging interpolation, and SatScan windows. The Mozambique shape file was available available at https://data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-moz.

Model building for multi-level analysis

DHS data exhibit nested dependencies, where individuals are nested within communities. It employs stratified, two-stage cluster sampling. Clusters (communities) are sampled, and within each cluster, households and individuals are further selected. We conducted a likelihood ratio test, comparing ordinary logistic regression to multilevel logistic regression. The results affirmed a significant improvement when using multilevel models, reinforcing their suitability. In summary, multilevel analysis of DHS data reveals the intricate web of nested dependencies, allowing us to disentangle individual and contextual effects.

Thus, using the traditional logistic regression model violates the assumptions of independent observation and equal variance across clusters. Therefore, a multi-level logistic regression analysis was employed in this study in order to account for the hierarchical nature of DHS data. A bivariate multi-level logistic regression model was employed in the study to identify the variables that might have an association with anemia. In the analysis, four models were fitted. The analysis was based on a weighted sample to mitigate the effect of any sample imbalance. The first (null) model contains only the outcome variables to test random variability and estimate the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). The second model contains individual-level variables; the third model contains only community-level variables; and the fourth model contains both individual-level and community-level variables39. Due to the hierarchical nature of the model, models were compared based on deviance, Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC). A model with the lowest information criteria (AIC and BIC) and deviance was selected as the best fit final model (model III). The selection of variables for the final model was based on a combination of theoretical relevance, empirical evidence, and statistical criteria. Initially, we included variables that were identified in the literature as significant predictors of the outcome. We then performed a stepwise selection process using both forward and backward elimination methods to refine the model. In addition, P-values for each covariate with the outcome variable (Anemia) were calculated using the Stata software with the command “tabulate dependent variable independent variable, chi2” for the chi-square association test, and p-values were also automatically generated in regression analysis. In our multilevel logistic regression analysis, we addressed the issue of multicollinearity by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each predictor variable. Variables with a VIF greater than 10 were considered to have high multicollinearity and were either removed or combined with other variables to reduce redundancy. Accordingly, in our multi-level analysis, the mean value of the VIF of the final model was 2.12.

Parameter estimation method

The fixed effects (a measure of association) were used to estimate the association between the likelihood of the prevalence of anemia and explanatory variables at both individual and community levels. The association between dependent and independent variables was assessed, and its strength has been presented using an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals with a p-value < 0.05. Hence, the log of the probability of anemia was modeled using a two-level multilevel model using the Stata syntax xtmelogit40.

logit (πij) = log [πij/ (1 − πij)] = β0 + β1xij + β2xij …. +u0j + e0ij,

Where, πij: the probability of the ith under-five to be anemic, (1 − πij), the probability of under-five children not having anemia β0: intercept, βn: regression coefficient indicating that a unit increase in x can cause a unit increase in the probability of having anemia, Xij: independent variables u0j: community-level error (the effect of the community having anemic children); e0ij: individual-level error. The clustered data nature and the within- and between-community variation were taken into account, assuming each community has a different intercept (βn) and fixed coefficient (β0)41.

Random effects (a measure of variation)

Variation of the outcome variable or random effects was assessed using the proportional change in variance (PCV), intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), and median odds ratio (MOR)42,43.

The ICC shows the variation in the burden of anemia due to community characteristics, which was calculated as: ICC = σ2/(σ2 + π2/3), where σ2 is the variance of the cluster44.The higher the ICC, the more relevant the community characteristics are for understanding individual variation in anemia.

MOR is the median value of the odds ratio between the areas with the highest burden of anemia and the area with the lowest burden of anemia when randomly picking out two younger children from two clusters, which was calculated as: MOR = e0.95√ σ2, where σ2 is the variance of the cluster. In this study, MOR shows the extent to which the individual probability of having anemia is determined by the residential area45.

Furthermore, the PCV illustrates how different factors account for variations in the prevalence of among under-five children and computed as PCV= (Vnull-Vc)/Vnull, where Vc is the cluster-level variance and Vnull is the variance of the null model46.

Spatial analysis

Spatial autocorrelation

For the spatial analysis, ArcGIS 10.7 and Sat Scan version 9.6 software were used. The spatial autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) statistics measure was used to evaluate whether the spatial distribution of under-five anemia was dispersed, clustered, or randomly distributed in Mozambique. Moran’s I value is spatial statistics used to measure spatial autocorrelation by taking the entire dataset and producing a single value that ranges from − 1 to 1. Moran’s I positive value indicates a clustered pattern of under-five anemia, while the negative value indicates a dispersed pattern, whereas Moran’s I close to zero indicates a random distribution of under-five anemia47,48.

Hot spot analysis (Getis-OridGi* statistics)

Getis-OrdGi* statistics were computed to measure how spatial autocorrelation varies over the study location by calculating Gi* for each area. Hot spot analysis (Getis-OridGi* statistics) of Z-score and p-value tells the feature with either hotspot or cold spot values for the cluster spatially. The hot spot area indicated that there was a higher proportion of under-five anemia, and the cold spot area indicated that there was a low proportion of under-five anemia.

Spatial interpolation

The spatial interpolation technique is used to predict under-five anemia for an unsampled area based on sampled clusters. This is done due to collecting reliable data in all areas of the country to know the burden of the problem; hence, parts of an unsampled area can be predicted by using sampled (observed) data by using a method known as interpolation. There are various geo-statistical interpolation methods. For our study, we used Kriging interpolation since it incorporates spatial autocorrelation that statistically optimizes the weight.

Spatial scan analysis

We employed Kulldorffs Bernoulli-based spatial scan statistic method version 9.6 software to detect the local spatial clusters of areas with high under-five anemia. Its output presents the hotspot areas in circular windows, indicating the areas inside the windows are higher than expected distribution compared to the area outside of the cluster windows. The scanning window that moves across the study area with under-five anemia was taken as cases, and those who did not develop anemia were taken as controls to fit the Bernoulli method. The default maximum spatial cluster size of < 50% of the population is used as an upper limit, allowing both small and large clusters to be detected. Most likely clusters were identified using p-values and log-likelihood ratio tests.

Ethics statement and consent to participate

The authors analyzed secondary, publicly available data obtained from the DHS program database. There was no additional ethical approval, and informed consent was obtained by the authors. In order to perform our study, we registered with the DHS web archive, requested the dataset, and were granted permission to access and download the data files. According to the DHS report, all participant data was anonymized during the collection of the survey data. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available online at http://www.dhsprogram.com.

Result

A total weighted sample of 3,127 child-mother pairs was included in the study. Of these, more than half (52.03%) of the children were female. The mean age of children was 33 months. Firstborn children account for one-fourth (25.00%) of the total number of children. Only one-tenth of children had diarrhea in the previous two weeks. More than one-third (37.11%) of children received deworming tablets in the last six months. More than one-third (37.16) of under-five children were stunted. The mean age of the mothers was 28 years ± 7 months. More than one-fourth (28.49%) of mothers had no formal education. More than half (54.93%) of mothers had antenatal care follow-up. More than three-fourths (54.32%) of mothers delivered in a health facility. The majority (86.93%) of mothers received iron supplementation during pregnancy. More than two-thirds (69.94%) of mothers had a normal body mass index. More than half (53.2%) of mothers were anemic. Nearly one-fourth (73.93%) of households were headed by males. Nearly half (48.1%) of households had improved water sources. More than two-thirds (68.37%) of participants were rural residents. Nearly half (46.91%) of the community was at a high community poverty level, and more than half (51.45%) of the community was at a high community women’s illiteracy level. Table 1.

National, and regional prevalence of anemia among under five children in Mozambique

The national prevalence of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique was 49.46% (95% CI: 47.70–51.21). The highest burden of anemia was observed in the Zambzia region (71.9%), and the lowest burden of anemia was observed in the Niassa region (21.95%) of Mozambique. (Fig. 1)

Spatial autocorrelation

The geographical autocorrelation analysis revealed that anemia among under five children in Mozambique revealed significant regional variation. The Global Moran’s index value, p-value, and Z-score values in this study were 0.086, 0.000782, and 3.36, respectively. This suggests that anemia among under-five children in Mozambique has significant geographic variation. (Fig. 2)

Hot spot analysis

Hot spot analysis was performed to identify high-risk areas of under-five anemia in Mozambique. The red color (hot spot) indicates significant risky areas and is found in Zambezia, Nampula, Safala, and the southern part of Gaza, whereas the blue color indicates less risky areas (clod spot) of under-five anemia and is observed in the western and southern parts of Niassa, the eastern part of Tete, the western part of Manica, and Maputo City of Mozambique. (Fig. 3)

Interpolation of egg and or/flesh consumption

Based on Mozambique Demographic and Health Survey sampled data, the Kriging interpolation predicts the highest prevalence of under-five anemia observed in Zambezia, Nampula, Sofala, and south and east of Carbo Delgado. In contrast, a relatively low prevalence of under-five anemia was detected in the northern part of Carbo Delgado, Niassa, Tete, the southern part of Manica, northern Gaza, the south and eastern parts of Inhambane, and Maputo City of Mozambique. (Fig. 4)

Spatial sat scan analysis anemia among under-five children in Mozambique

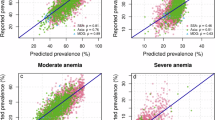

A total of 251 significant clusters were identified, of which ninety-one (91) were most likely (primary) clusters. The primary cluster spatial window was located in Zambzia, centered at a radius of 17.269259 S, 37.822882 E, or 277.67 km, with a log-likely hood ratio (LLR) of 124.26, an RR of 1.58, and a P-value of 0.001. This indicates children within the spatial window had a 1.58 times higher anemia rate as compared to children outside the window. The secondary clusters spatial window was also located in Zambzia, centered at a radius of 17.269259 S, 37.822882 E) / 256.66 km with a LLR of 114.86 and RR of 1.58 at a p-value < 0.001. This means that children in the SaTScan window were 1.58 times more at risk of anemia as compared to children outside the SaTScan window. The tertiary cluster spatial window was located in Nampula, centered at a radius of (14.559803 S, 40.689502 E)/166.13 km with an LLR of 27.58, an RR of 1.3, and a p-value of < 0.001. This indicates that children within the spatial window had 1.3 times more risk of developing anemia as compared to children outside the spatial window. The fourth and fifth spatial SaTScan widows were located in the Manica and Sofala regions. (Table 2, Fig. 5).

Random effect and model fit statistics

As shown in Table 3, the ICC in the null model was 0.27, indicating that 27.85% of the variations in anemia among under-five children were attributed to cluster differences, while the remaining 72.5% were attributed to individual-level factors. The median odds ratio (MOR) value of 2.92 in the null model also indicated that the odds of anemia among study subjects were different between clusters. Furthermore, the PCV revealed that 70.86% of the variation in anemia among study subjects was explained by the final model with the lowest deviance, which was the better-fitted model, which was model III, and was selected for interpretation by the final model (model III). Regarding model comparison and fitness, deviance, AIC, and BIC were used. The model with the lowest deviance, AIC and BIC, was the best-fitted model, which was model III, and was selected for interpretation (Table 3).

Multilevel logistic regression

In multivariable multilevel logistic regression analysis, father education, anemic mothers, and region were significantly associated with anemia among under-five children in Mozambique.

Children with fathers with no formal education were 82% more likely (AOR = 1.82; 95% CI, 1.07–3.07) to have anemia as compared to children with fathers who completed secondary education and above. Children from anemic mothers were 61% more likely (AOR = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.11–2.32) to be anemic as compared to children from non-anemic mothers. Children whose mothers were underweight were 45% more likely (AOR = 1.45; 95% CI, 11.02–2.08) to be anemic as compared to average-weighted mothers. Children residing in the Zambzia region had 3.59 higher odds (AOR = 3.59; 95% CI, 1.28–10.12) of anemia as compared to Maputo city. Similarly, children residing in the Nampula region had 2.61 higher odds (AOR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.02–6.03) of anemia as compared to Maputo City. On the other hand, children residing in the Niassa region had 65% reduced odds (AOR = 0.35; 95% CI = 0.13–0.94) of anemia as compared to children residing in Maputo City. (Table 4)

Discussion

This study also revealed that the national prevalence of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique was 49.46% (95% CI: 47.70–51.21). This study also found that anemia among under-five children is not random at the national and regional levels in Mozambique. Significant clusters of under-five anemia in Mozambique were discovered in Zambezia, Nampula, Safala, and the southern part of Gaza, whereas the blue color indicates less risky areas (clod spots) of under-five anemia and is observed in the western and southern parts of Niassa, the eastern part of Tete, the western part of Manica, and Maputo City. This is supported by prior study in the country49,50. One probable explanation is that the malaria prevalence among children under the age of five was greater in Zambezia and Nampula, whereas it was lower in Maputo province and Maputo city. Malaria is the most common cause of anemia, which explains the disparity in anemia among regions that might be caused by malaria51. In addition, the most populous provinces, Zambezia and Nampula, have the poorest education and health outcomes; and in general, the northern provinces have poorer infrastructure, high plasmodium falciparum malaria, higher levels of environmental degradation, and lower economic activity than the south, which predispose under-five children to parasitic infestation, frequent infection, and under nutrition like iron deficiency, which in turn causes under-five anemia49,52. Furthermore, Zambezia and Nampula, where food insecurity is common, limited aces to health care facilities, and a high burden of infectious disease, are largely rural and impoverished and often rely on staple foods like cassava or maize that are low in micronutrients, leading to a higher rate of anemia.

The prevalence of anemia among under-five children was comparable with the study done in Cape Verde (51.8%)53, Nepal (52.6)29. One probable explanation is that anemia is linked to socioeconomic, biological, environmental, and nutritional factors common to lower and middle income countries54. In addition, low and middle-income countries had lower levels of access to safe drinking water, malnutrition, communicable and non-communicable diseases, poor sanitation and hygiene, a higher level of pollution, open defecation, and poor quality infrastructure55,56, all of these prone under-five children to anemia.

The prevalence of under-five anemia in Mozambique were lower than the study done in Togo (70.9%), Ghana (54%), five south and south east Asia (57.3%), Zanzibar (69.1%), Nigeria (67.01%), Ethiopia (58%), sub-Saharan African studies (64.1%) and prior study in Mozambique (69.8%)30,33,57,58,59,60,61. However, the prevalence of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique was higher than the systematic review report in 204 countries (39.7%) and global report (39.8%)62,63. The lower prevalence in Mozambique could be explained by the country’s implementation of fortification of staple foods, micronutrient supplementation, malaria control efforts, poverty reduction efforts, a focus on maternal health, and better exclusive feeding practices, all of which contributed to the low burden of anemia as compared to other African countries. In addition, though the country remains low-income, localized efforts have improved food access and diversity in certain areas, which impacts anemia levels64,65. On the other hand, the higher prevalence as compared to the global prevalence could be explained by the lower economy, and despite control measures, there is a high prevalence of malaria in the country responsible for a higher prevalence of under-five anemia66.

The odds of developing under-five anemia among children whose mothers were anemic were higher compared to those of children whose mothers were not anemic. This finding is in line with other studies done in different parts of the world20,57,67,68. This could be due to the fact that these children share common characteristics with their mother, including the same and similar food and socio-economic conditions69. If the food source is low in iron, children and mothers are at risk of developing iron-deficiency anemia. Furthermore, their surroundings may expose them to parasite infestations such as roundworm and hookworm, resulting in a higher rate of infestation among mothers and children that leads to anemia in both groups. Furthermore, because these moms are already iron deficient, their breast milk may not contain enough iron to meet their children’s physiological iron demand70. Therefore, iron supplementation, deworming, and other interventions shall be strengthened to lower the incidence of under-five anemia.

This study confirmed that children from fathers with secondary education and above had lower odds of anemia as compared to children from uneducated father. This is supported by the study done in India71, Sri Lanka72 and Nepal67. The possible explanation might be educated parents may have a higher income, which may further have a bearing in improving a child’s nutrition and feeding practice73. In addition, educated fathers may conceive health messages, including deworming from the health care profession, early diagnosis and treatment of malaria, and appropriate use of nutrition that will help to lower anemia. Therefore, educating parents is one crucial step to reduce anemia in under-five children.

Children from low maternal body mass index (BMI) mothers had higher odds of anemia as compared to children from normal body mass index mothers. This is supported by other studies74. This is explained by the fact that low maternal BMI is frequently associated with various micronutrient deficits, such as iron, vitamin A, or B675,76. These deficits interfere with iron mobilization and use in the process of hemoglobin synthesis, which increases maternal anemia risk77,78 and then to increase offspring anemia risk79.

Regions were significantly associated with anemia among under-fives in Mozambique; accordingly, children who resided on the countryside (region) including Zambezia and Nampula were more likely to develop anemia as compared to children who were living in city administration (Maputo city). This in line with prior study in Mozambique50,51. The possible explanation for this variation could be a difference in the variation of environmental, socio-economic, and cultural practices among regions. In addition, the most populous provinces, Zambezia and Nampula, have the poorest education and health outcomes, and in general, the Northern provinces have poorer infrastructure and high plasmodium falciparum malaria, which might increase the odds of anemia in these regions52. Therefore, special attention should be given to the Zambezia and Nampula regions of Mozambique.

Children living in the Niassa region were less likely to be anemic as compared to children residing in Maputo province. This is contrary to previous findings80. The possible explanation could be that sub-Saharan African countries, including Mozambique, work against under nutrition and anemia in under-five children; for instance, the prevalence of anemia declined from 70.2 to 49.46 in 2018–202380.

This study has its own strengths and limitations. This study is based on the most recent national data (DHS) that provides current and up-to-date evidence at the country level. In addition, the data was weighted, and a spatial analysis with a multilevel model was augmented to get a reliable estimate of under-five anemia. As a limitation, since the study used cross-sectional data, we cannot establish a causal relationship between anemia and an independent variable. Besides, since this study was based on demographic and health survey data, all factors responsible for under-five anemia, including parasitic infestation, previous hospitalization, trauma, other comorbidities, and use of nutritional supplements like vitamin B12 and folate, were not investigated as predictors. Furthermore, variables such as the birth size of a child were subjective measurements since the measured birth weight of a child was not found for the majority of children, which might overestimate or underestimate the effect size. Above all, due to the DHS nature of data, hard-to-reach areas/marginalized populations accessing data was difficult; thus, underrepresentation of under-five anemia might occur. Therefore, we recommend future researchers to investigate the burden and associated factors of under-five anemia by accounting for the aforementioned proximal factors of under-five anemia using more advanced models like machine learning approaches to identify the most adversely affected regions and to identify strong predictors of under-five anemia in Mozambique by performing interactions between each independent variable.

Conclusions

The burden of under-five anemia in Mozambique is a major or severe public health problem. Maternal anemia, underweighted mothers, husband education, and regions in Mozambique were significantly associated with under-five anemia. Improving the nutritional status of mothers and interventions to address maternal anemia, with special attention to the Nampula and Zambzia regions, are recommended to reduce under-five anemia.

Data availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The name of repositories/repository access number/s can found below: http://www.dhsprogram.com/.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criteria

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criteria

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- EA:

-

Enumeration area

- ICC:

-

Inter cluster correlation

- LR:

-

logistic regression

- MOR:

-

Median Odds Ratio

- SSA:

-

Sub-Sahara Africa

- PCV:

-

Proportional Change in Variance

- PNC:

-

Post Natal Care

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children Emergency Fund

References

Gao, J. & Monaghan, S. A. Red Blood cell/hemoglobin Disordersp. 3–56 (Elsevier, 2018). e2.

Organization, U. N. W. H. Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Assesment, Prevention and Control: A Guide for Programme Managers (World Health Organization, 2001).

Brabin, B. J., Premji, Z., Verhoeff & FJTJon Anal. anemia Child. Mortal. ;131(2):636S–48S. (2001).

Ramakrishnan, U. Functional Consequences of Nutritional anemia during Pregnancy and Early Childhood (CRC Press, LLC, 2001).

Villalpando, S., Shamah-Levy, T., Ramírez-Silva, C. I., Mejía-Rodríguez, F. & Rivera, J. A. J. S. M. Prevalence of anemia in children 1 to 12 years of age: results from a nationwide probabilistic survey in Mexico. ;45:490–498. (2003).

Cornet, M. et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for anemia in young children in southern Cameroon. ;58(5):606–611. (1998).

Unicef, U. & WHO UJAgfpm. WHO: Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention, and control. (2001).

Brabin, B. J., Hakimi, M., Pelletier & DJJn Iron-deficiency anemia: reexamining the nature and magnitude of the public health problem. ;131:636S–48S. (2001).

https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children

Kassebaum, N. J. et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. ;123(5):615–624. (2014).

Lozoff, B., Jimenez, E. & Wolf, A. W. J. N. E. Long-term developmental outcome of infants with iron deficiency. ;325(10):687–694. (1991).

Abu-Ouf, N. M. & Jan, M. M. J. S. The impact of maternal iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia on child’s health. ;36(2):146. (2015).

Shaw, J. G. & Friedman, J. F. J. A. Iron deficiency anemia: focus on infectious diseases in lesser developed countries. ;2011(1):260380. (2011).

Balarajan, Y., Ramakrishnan, U., Özaltin, E. & Shankar, A. H. Subramanian SJTl. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. ;378(9809):2123-35. (2011).

Khan, J. R., Awan, N. & Misu, F. J. B. Determinants of anemia among 6–59 months aged children in Bangladesh: evidence from nationally representative data. ;16:1–12. (2016).

Kawo, K. N., Asfaw, Z. G. & Yohannes, N. J. A. Multilevel analysis of determinants of anemia prevalence among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: classical and bayesian approaches. ;2018(1):3087354. (2018).

Onyeneho, N. G., Ozumba, B. C. & Subramanian, S. J. S. Determinants Child. anemia India ;9(1):16540. (2019).

Gupta, S., Venkateswaran, R., Gorenflo, D. W. & Eyler AJPm. Childhood iron deficiency anemia, maternal nutritional knowledge, and maternal feeding practices in a high-risk population. ;29(3):152–156. (1999).

Habte, D. et al. Maternal risk Factors Child. Anaemia Ethiopia ;17(3):110–118. (2013).

Leite, M. S. et al. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among indigenous children in Brazil: results from the First National Survey of Indigenous people’s. Health Nutr. 12, 1–11 (2013).

Pasricha, S-R. et al. Determinants anemia among Young Child. Rural India ;126(1):e140–e9. (2010).

UNICEF S. The State of the World’s Children 2009-Executive Summary: Maternal and Newborn Health (United Nations Children’s Fund The UNICEF, 2008).

McLean, E., Cogswell, M., Egli, I., Wojdyla, D. & De Benoist, B. J. P. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. ;12(4):444–454. (2009).

Censo, I. J. M. I. divulgação dos resultados preliminares. (2017).

https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/mozambique-population/

https://www.countryreports.org/country/Mozambique/geography.htm

Wegmüller, R. et al. Anemia, micronutrient deficiencies, malaria, hemoglobinopathies and malnutrition in young children and non-pregnant women in Ghana: findings from a national survey. ;15(1):e0228258. (2020).

Chowdhury, M. R. K. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of childhood anemia in Nepal: a multilevel analysis. ;15(10):e0239409. (2020).

Aheto, J. M., Alhassan, Y., Puplampu, A. E., Boglo, J. K. & Sedzro, K. M. J. H. S. R. Anemia prevalence and its predictors among children under-five years in Ghana. A multilevel analysis of the cross‐sectional 2019 Ghana Malaria Indicator Survey. ;6(10):e1643. (2023).

Worku, M. G. et al. Multilevel analysis of determinants of anemia among young women (15–24) in Sub-sahara Africa. ;17(5):e0268129. (2022).

Yadav, J., Nilima, N. J. C. E. & Health, G. Geographic variation and factors associated with anemia among under-fives in India: a multilevel approach. ;9:261–268. (2021).

Tesema, G. A. et al. Prevalence and determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in sub-saharan Africa: a multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. ;16(4):e0249978. (2021).

Seifu, B. L. & Tesema, G. A. J. A. P. H. Individual-and community-level factors associated with anemia among children aged 6–23 months in sub-saharan Africa: evidence from 32 sub-saharan. Afr. Ctries. 80 (1), 183 (2022).

Alamneh, T. S., Melesse, A. W. & Gelaye, K. A. J. S. R. Determinants of anemia severity levels among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia. Multilevel Bayesian Stat. Approach. 13 (1), 4147 (2023).

Anteneh, Z. A. & Van Geertruyden, J-P-J-P. Spatial variations and determinants of anemia among under-five children in Ethiopia, EDHS 2005–2016. ;16(4):e0249412. (2021).

Gebremeskel, M. G. et al. Individual and community level factors associated with anemia among children 6–59 months of age in Ethiopia: a further analysis of 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. ;15(11):e0241720. (2020).

Sommet, N. & Morselli, D. J. I. R. S. P. Keep calm and learn multilevel logistic modeling: a simplified three-step procedure using Stata, R, mplus, and SPSS. ;30:203–218. (2017).

Goldstein, H. Multilevel Statistical Models (Wiley, 2011).

Snijders, T. A. & Bosker, R. Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. (2011).

Penny, W. Holmes AJSpmTaofbi. Random Eff. Anal. 156, 165 (2007).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V. & Higgins, J. P. Rothstein HRJRsm. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random‐effects models for meta‐analysis. ;1(2):97–111. (2010).

Rodriguez, G. & Elo, I. J. T. S. J. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. ;3(1):32–46. (2003).

Merlo, J. et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. ;60(4):290–297. (2006).

Tesema, G. A., Mekonnen, T. H. & Teshale, A. B. J. P. Individual and community-level determinants, and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia, 2016: spatial and multilevel analysis. ;15(11):e0242242. (2020).

Waldhör TJSiM. The spatial autocorrelation coefficient Moran’s I under heteroscedasticity. ;15(7-9):887–892. (1996).

Anselin, L. & Getis, A. J. T. A. R. S. Spatial statistical analysis and geographic information systems. ;26:19–33. (1992).

Mabunda, S., Casimiro, S., Quinto, L., Alonso & PJMj A country-wide malaria survey in Mozambique. I. Plasmodium falciparum infection in children in different epidemiological settings. ;7:1–11. (2008).

Muhajarine, N., Adeyinka, D. A., Matandalasse, M. & Chicumbe, S. J. Inequities in childhood anaemia in Mozambique: results from multilevel bayesian analysis of 2018 National Malaria Indicator Survey. 2021:2021.03. 24.21252471.

Ejigu BAJPo. Geostatistical analysis and mapping of malaria risk in children of Mozambique. ;15(11):e0241680. (2020).

Mahrt, K., Rossi, A., Salvucci, V. & Tarp, F. J. C. I. R. Multidimensional Poverty Child. Mozambique ;13(5):1675–1700. (2020).

Semedo, R. M., Santos, M. M., Baião, M. R. & da Luiz, R. R. Veiga GVJJoh, population, nutrition. Prevalence of anaemia and associated factors among children below five years of age in Cape Verde. West. Afr. 32 (4), 646 (2014).

Santos RFd, Gonzalez, E. S. C., Albuquerque ECd, A., IKGd, D. & Figueroa, A. S. Prevalence of anemia in under five-year-old children in a children’s hospital in Recife. Brazil 33, 100–104 (2011).

Alhaji, M. M. & Alam, S. J. J. P. M. I. Health policy and system research in global south: bridging the gap through citizen participation. ;33(1). (2019).

Haileamlak AJEJoHS. The triple challenges of low and middle-income countries. ;28(1):1–2. (2018).

Nambiema, A., Robert, A. & Yaya, I. J. B. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia in children aged from 6 to 59 months in Togo: analysis from Togo demographic and health survey data, 2013–2014. ;19:1–9. (2019).

Asresie, M. B., Fekadu, G. A. & Dagnew, G. W. J. A. P. H. Determinants of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic health survey. ;2020(1):3634591. (2020).

Anjorin, S. & Yaya, S. J. M. nutrition c. Anaemia among under-five children: Is maternal marriage at 18th birthday and above protective? Evidence from 15 countries in Sub‐Saharan Africa. ;17(4):e13226. (2021).

Sunuwar, D. R. et al. Factors associated with anemia among children in South and Southeast Asia: a multilevel analysis. ;23(1):343. (2023).

Khatib, A. H. & Joho, A. A. J. I. J. A. N. S. Prevalence of anaemia and caregivers’ knowledge, practice and attitude towards its prevention among under-fives in Zanzibar, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. ;16:100416. (2022).

Gardner, W. Kassebaum NJCDiN. Global, regional, and national prevalence of anemia and its causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. ;4:nzaa053_35. (2020).

https://www.bing.com/ck/the+global+burden+of+Under-five+anemia

Amaro, M. J. M. & Nutrition, C. Accelerating progress in micronutrient deficiencies in Mozambique: A Ministry of Health perspective. ;15(Suppl 1). (2019).

https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/Copy_of_tagged_Mozambique-Nutrition-Profile.pdf

Organization, W. H. Report of the First and Second Meetings of the Technical Advisory Group on Malaria Elimination and Certification, 13–14 September 2022 and 27 January 2023 (World Health Organization, 2023).

Khanal, V., Karkee, R. & Adhikari, M. Gavidia TJCe, health g. Moderate-to-severe anaemia among children aged 6–59 months in Nepal: an analysis from Nepal demographic and health survey, 2016;4(2):57–62. (2011).

Al-Qaoud, N. M., Al-Shami, E. & Prakash, P. J. A. J. M. Anemia and associated factors among Kuwaiti preschool children and their mothers. ;51(2):161–166. (2015).

Zhao, A. et al. Prevalence of anemia and its risk factors among children 6–36 months old in Burma. ;87(2):306. (2012).

Gao, W., Yan, H., DuolaoWang, Dang, S. & Pei, L. J. P. Severity of anemia among children under 36 months old in rural western China. ;8(4):e62883. (2013).

Kumar, P., Chauhan, S., Patel, R. & Srivastava, S. J. B. Anaemia among mother-father-child pairs in India: examining co-existence of triple burden of anaemia in a family. ;21:1–8. (2021).

Malkanthi, R., Silva, K., Jayasinghe-Mudalige, U. K. J. F. & Bulletin, N. Risk factors associated with high prevalence of anemia among children under 5 years of age in paddy-farming households in Sri Lanka. ;31(4):475–482. (2010).

Xin, Q-Q. et al. Prevalence of anemia and its risk factors among children under 36 months old in China. ;63(1):36–42. (2017).

Yin, S. et al. Association of maternal BMI during early pregnancy with infant anemia: a large Chinese birth cohort. ;17:1–8. (2020).

Huddle, J., Gibson, R., Cullinan & TJEjocn The impact of malarial infection and diet on the anaemia status of rural pregnant Malawian women. ;53(10):792–801. (1999).

Gibson, R. S. et al. Zinc, gravida, infection, and iron, but not vitamin B-12 or folate status. Predict Hemoglobin Dur. Pregnancy South. Ethiopia. 138 (3), 581–586 (2008).

Suharno, D., Karyadi, D., West, C. & Hautvast, J. G. J. T. Supplementation with vitamin A and iron for nutritional anaemia in pregnant women in West Java. Indonesia 342 (8883), 1325–1328 (1993).

Hisano, M., Suzuki, R., Sago, H. & Murashima, A. Yamaguchi KJEjocn. Vitamin B6 deficiency and anemia in pregnancy. ;64(2):221–223. (2010).

De Pee, S. et al. The high prevalence of low hemoglobin concentration among Indonesian infants aged 3–5 months is related to maternal anemia. ;132(8):2215–2221. (2002).

Muhajarine, N., Adeyinka, D. A., Matandalasse, M. & Chicumbe, S. J. B. O. Inequities in childhood anaemia at provincial borders in Mozambique: cross-sectional study results from multilevel bayesian analysis of 2018. Natl. Malar. Indicator Surv. 11 (12), e051395 (2021).

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Berhan Tekeba made conceptualization, drafted the original manuscript, and made software analysis. Mulugeta Wassie designed and ran the analysis. Tasesse Tarik Tamir: made supervision, editing and tool validation. Enyew Gethaneh Mekonen: made investigation, formal analysis, and methodology. Agahze Aemro checked the analysis and made substantial contributions in reviewing the design of the study, the draft manuscript edits, and the review abstract. He critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and contributed to the final approval of the version to be submitted. All listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tekeba, B., Wassie, M., Mekonen, E.G. et al. Spatial distribution and determinants of anemia among under-five children in Mozambique. Sci Rep 15, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83899-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83899-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among newborns in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Pediatrics (2025)

-

Geospatial modeling of under-five mortality in Iraq based on geographic weighted regression model

Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics (2025)