Abstract

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors have been increasingly recognized for their potential neuroprotective properties. Nevertheless, their effects on intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are still debated, with the precise mechanisms involved remaining unclear. Recent studies indicate that these inhibitors might lower ICH risk through anti-inflammatory mechanisms. This study analyzed genome-wide association study (GWAS) data from individuals of European ancestry, focusing on the relationship between 92 inflammatory biomarkers and ICH. A two-sample, two-step Mendelian randomization (MR) approach was used to examine the potential connection between SGLT-2 inhibition and ICH, as well as to investigate whether inflammatory biomarkers mediate this relationship. Genetic proxies for SGLT-2 inhibition were determined based on variants linked to the expression of the SLC5A2 gene and levels of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to assess the associations between SGLT-2 inhibition, inflammatory biomarkers, and the likelihood of ICH. The genetic prediction of SGLT-2 inhibition was found to be inversely related to the risk of ICH (OR = 0.152; 95% CI = 0.066–0.352; P < 0.001). Out of the 92 inflammatory biomarkers examined, 33 showed a significant association with SGLT-2 inhibition. Notably, levels of IL10 receptor subunit beta (IL10RB) were significantly correlated with both SGLT-2 inhibition and ICH. Moreover, IL10RB accounted for 9.167% of the total mediation effect of SGLT-2 inhibition on ICH. The findings of this study suggest a link between SGLT-2 inhibition and a decreased risk of ICH, with IL10RB emerging as a possible mediator. This presents a potential new strategy for ICH prevention and intervention. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of inflammatory pathways in the connection between SGLT-2 inhibition and ICH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) represents 20–30% of all acute stroke cases and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality1. The one-year mortality rate following ICH exceeds 50%, and survivors often suffer from functional and cognitive impairments, imposing a heavy burden on society and families1. Several factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, and obesity, are established risk contributors to ICH3. Specifically, DM elevates the risk of ICH through pathways involving inflammation, oxidative stress, atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, vascular damage, and platelet activation, all of which can weaken the cerebral vasculature5. These factors collectively compromise the integrity of cerebral blood vessels. As a result, people with DM are not only more prone to developing ICH but also to experiencing higher rates of complications and stroke recurrence7. Recent systematic reviews have shown that people with DM have higher mortality rates within 30 days post-ICH or by discharge compared to non-diabetic individuals9. Therefore, controlling blood glucose levels and managing DM is crucial for individuals at high risk of ICH.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors represent a novel class of oral antidiabetic drugs. These medications work by blocking the reabsorption of glucose in the renal tubules, specifically in the proximal portion, thereby increasing glucose excretion through urine and reducing blood glucose levels10. Beyond their glucose-reducing effects, substantial evidence indicates that SGLT2 inhibitors enhance cardiovascular outcomes, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and renal function14. Recent research also suggests these inhibitors have anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic effects within the central nervous system, such as decreasing pro-inflammatory factors, promoting M2 macrophage activity, inhibiting inflammatory responses, and alleviating oxidative stress15. These properties contribute to neuroprotection. Despite their established cardiovascular and renal benefits for individuals with type 2 diabetes, the effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors in decreasing the risk of hemorrhagic stroke is still seen as moderate and varies across studies16. Emerging research posits that combining SGLT1 and SGLT2 inhibitors might notably lower stroke risk18. Therefore, further investigation is warranted to explore the causal relationship between SGLT2 inhibitors and the risk of ICH. Previous studies have identified deep penetrating vessel disease and small artery atherosclerosis as primary causes of ICH, involving complex inflammatory and immune responses19. Experimental studies in cellular and animal models have further validated the anti-inflammatory effects of SGLT2 inhibitors15. Thus, it is plausible that SGLT2 inhibitors may influence ICH risk by modulating inflammatory responses.

Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis is a method for determining causal relationships using the principles of Mendelian inheritance, which involves the random assignment of alleles during the formation of gametes22. This randomness makes MR analysis similar to a natural randomized controlled trial, effectively reducing the impact of confounding variables. In MR studies, genetic variants linked to the exposure of interest are used as instrumental variables to infer a causal connection between the exposure and the outcome24. In this research, a two-sample MR analysis was initially conducted to explore the link between SGLT2 inhibition and ICH. This was followed by a two-step MR approach involving 92 inflammatory biomarkers to identify potential pathways through which SGLT2 inhibitors may affect ICH risk. This methodology sheds light on how the anti-inflammatory properties of SGLT2 inhibition could influence the likelihood of ICH. Additionally, considering that hypertension is a known risk factor for ICH and that SGLT2 inhibitors have antihypertensive effects, this study also examined the possibility that these inhibitors might reduce ICH risk through blood pressure regulation. However, since the primary focus of this study is on the anti-inflammatory effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in relation to ICH, the blood pressure-lowering effects are not the main emphasis.

Method

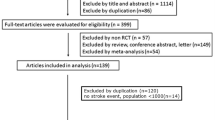

To establish the validity of causal effects, a two-sample MR design was utilized. Then, a two-step MR analysis was performed to explore the potential impacts of mediating variables (Fig. 1). MR analysis is grounded in three core assumptions (Fig. 1). MR analysis is based on three fundamental assumptions22: (1) the instrumental variables (IVs) must be correlated with the exposure being studied; (2) IVs must be independent of any potential confounders that could skew the causal link between the exposure and the outcome; (3) IVs should affect the outcome exclusively through their influence on the exposure, avoiding any pleiotropic effects.

Data for this analysis were obtained from publicly available genome-wide association studies (GWAS), specifically the IEU OPENGWAS project, UK Biobank, and FinnGen dataset. These datasets are openly downloadable and do not include individual-level data, thereby eliminating the requirement for additional ethical review.

GWAS data for SGLT‑2 inhibitors

Following established research protocols, our study started with the identification of genetic variants linked to SGLT2 inhibition25. To achieve this, we first used publicly accessible data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project26 and the eQTLGen Consortium27 to pinpoint genetic variants associated with mRNA expression levels of the SLC5A2 gene, which codes for the SGLT2 protein. Subsequently, we assessed the relationship between these identified variants and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, which serve as an indicator of glucose-lowering effects. We focused on variants demonstrating a significant association with HbA1c (P < 1 × 10−4). This analysis utilized data from the UK Biobank, specifically examining 344,182 unrelated European individuals without a diabetes mellitus diagnosis28. To explore whether the SLC5A2 gene and HbA1c levels share common causal variants, we carried out a colocalization analysis, considering a posterior probability above 70% as evidence of shared causality29. Specifically, we assessed the posterior probabilities of colocalization between SNPs associated with SGLT-2 inhibition and the significant biomarkers identified in our study. If the probability exceeded the threshold, we considered the variants to be shared causal variants. Finally, to minimize redundancy in the dataset, a clumping analysis was performed using the European reference panel from the 1,000 Genomes Project, organizing genetic variants into linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks with an r2 of 0.8 and a physical distance of 250 kb.

GWAS data for infammatory biomarkers and hypertension

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) was conducted to investigate genetic variants associated with 91 different inflammatory biomarkers. This study included 14,824 participants of European ancestry, with accession numbers from GCST90274758 to GCST9027484830. Additionally, particular focus was given to C-reactive protein (CRP), a commonly studied inflammation marker. Genetic data for CRP-related variants were analyzed from a large European cohort of 575,531 individuals, as reported by Dehghan et al.31. Using standard criteria for selecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), a significance threshold of P < 5 × 10-8 was applied to identify SNPs linked to inflammatory markers. To mitigate issues associated with linkage disequilibrium (LD), the identified SNPs were grouped with a threshold set at kb = 10,000 and r2 = 0.00132. The strength of the genetic instruments was assessed using the F statistic, and SNPs with an F value below 10 were excluded to minimize the risk of bias from weak instruments33. To further refine the analysis, PhenoScanner (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) was used to identify any SNPs associated with other traits at a genome-wide significance level, and potentially pleiotropic SNPs were excluded. The GWAS data on hypertension was sourced from a European cohort of 484,598 individuals.

GWAS data for intracerebral hemorrhage

The GWAS for ICH utilized data from the FinnGen project, which comprised 7,040 cases and 374,631 controls, all of European descent (https://www.finngen.fi/en). The FinnGen initiative is a broad, open-access genetic research project that draws on samples from various Finnish populations. Its main objective is to perform GWAS to identify genetic variants associated with different diseases and health traits. The dataset offers a wealth of genomic, clinical, and biosample information, facilitating research into a diverse array of conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, metabolic disorders, and neurological ailments34. Detailed information on the GWAS data can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis

In our research, the Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) method is employed as the primary analytical approach, as it provides the most accurate and dependable estimates35. The IVW method combines the individual SNP-exposure associations weighted by the inverse of their variances, providing more precise estimates for the causal effect. Specifically, each SNP-exposure association is weighted according to the inverse of its variance, with larger weights assigned to SNPs that are more strongly associated with the exposure (SGLT-2 inhibition). This method assumes no unmeasured confounding and a linear relationship between the genetic instrument and the outcome, and it is considered the most accurate approach when the instrument is strong and no horizontal pleiotropy is present.

Furthermore, five other methods are utilized: MR Egger method is suitable for handling potential horizontal pleiotropy by adjusting for intercept bias to provide robust estimates36 ; Weighted Median method provides robust estimates in scenarios where effects of a few SNPs are inconsistent37; Robust Adjusted Profile Score (RAPS) method adjusts for pleiotropy while maintaining accuracy38; Weighted Mode method is suitable when most SNP effects are consistent39; and Bayesian analysis quantifies uncertainty in causal estimates, applicable in complex data contexts40. The combined use of these methods helps reduce bias and enhances consistency and reliability of results in MR analysis.

To investigate how inflammatory biomarkers mediate the association between SGLT-2 inhibitors and ICH, we conducted a two-step MR analysis to assess these mediation effects (see Fig. 2). First, we evaluated the overall effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on ICH (β0). Next, we used a univariate MR approach to determine the impact of SGLT-2 inhibitors on 92 inflammatory markers (β1). We then identified the inflammatory markers significantly associated with SGLT-2 inhibitors and estimated their effects on ICH (β2). The mediation effect of each inflammatory marker on the relationship between SGLT-2 inhibitors and ICH was calculated using the coefficient product method (β1 × β2), with the proportion of mediation determined as [β1 × β2] / β041.

Flowchart of the two-sample and two-step Mendelian randomization evaluating the mediating effect of inflammatory biomarkers on the impact of SGLT-2 inhibition on ICH. HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin, GWAS, genome-wide association study, pQTL, protein quantitative trait loci, SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism, LD, linkage disequilibrium, CRP, C-reactive protein, SGLT-2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2, MR, Mendelian randomization.

Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analysis, Cochran’s Q statistic was utilized to assess heterogeneity among the instrumental variables (IVs). The MR-Egger intercept method was employed to test for horizontal pleiotropy; a non-zero intercept indicates potential horizontal pleiotropy and bias in the IVW estimates36. Additionally, the MR-PRESSO method was used to detect horizontal pleiotropy by identifying outliers and recalculating estimates after their removal. To address multiple hypothesis testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied to adjust for the false discovery rate (FDR)42, with a q-value ≤ 10% deemed statistically significant25. These methods collectively aim to reduce biases and confounding factors, thereby enhancing the reliability of causal inferences between genetic variants and outcomes.

Effect estimates are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and statistical significance is determined by a two-sided P-value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the “TwoSampleMR” package (version 0.6.11) in R software (version 4.3.3).

Results

Effect of SGLT-2 inhibition on ICH

14 independent independent SNPs were selected as genetic instruments for SGLT-2 inhibition, each with an F-statistic greater than 10 (see Supplementary Table S2), with values ranging from 24.55 to 48.12, indicating that the instruments used in this study are strong and have minimal risk of weak instrument bias. This strong association between the SNPs and the exposure ensures the reliability of our instrumental variable approach and strengthens the validity of the causal inference. The analysis indicated a significant association between SGLT-2 inhibition and a reduced risk of ICH (OR = 0.152; 95% CI = 0.066–0.352; P < 0.001). This suggests that SGLT-2 inhibitors are associated with a marked reduction in the risk of ICH. The results from the IVW method were robust and consistent, with no evidence of heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy among the genetic instruments used (Q = 7.101, P = 0.897) (Table 1).

Effect of SGLT-2 inhibition on inflammatory biomarkers and hypertension

We evaluated the effect of SGLT-2 inhibition on 92 circulating inflammatory biomarkers and identified significant associations with 33 of these markers (see Figs. 3 and 4, and Supplementary Table S3). SGLT-2 inhibitors were found to decrease levels of several inflammatory markers, including C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 23 (CCL23) (OR = 0.588; 95% CI = 0.352–0.983; P = 0.043; FDR-adjusted P = 0.043), Cystatin D (CST5) (OR = 0.583; 95% CI = 0.350–0.969; P = 0.037; FDR-adjusted P = 0.038), and C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10 (CXCL10) (OR = 0.555; 95% CI = 0.332–0.927; P = 0.024; FDR-adjusted P = 0.026). Conversely, these inhibitors were associated with increased levels of inflammatory markers such as CCL19 (OR = 1.854; 95% CI = 1.102–3.116; P = 0.020; FDR-adjusted P = 0.025) and CCL20 (OR = 2.837; 95% CI = 1.692–4.756; P < 0.001; FDR-adjusted P < 0.001). Additionally, SGLT-2 inhibitors were found to lower the risk of hypertension (OR = 0.937; 95% CI = 0.904–0.971; P < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses revealed no evidence of heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy among the genetic instruments (all P > 0.05).

Effect of inflammatory biomarkers and hypertension on ICH

Among the 33 inflammatory biomarkers linked to SGLT-2 inhibition, IL10RB demonstrated a negative association with ICH (OR = 0.929; 95% CI = 0.876–0.986; P = 0.015; FDR-adjusted P = 0.029). Neither Cochran’s Q test (Q = 13.357, P = 0.421) nor the MR Egger intercept method (Egger intercept = 0.005, P = 0.629) indicated evidence of heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy. Additionally, hypertension was identified as a significant risk factor for ICH (OR = 4.906; 95% CI = 3.348–7.190; P = 0.000). Although Cochran’s Q statistic showed significance (P < 0.05), a random-effects model was utilized to address potential variability43. In addition to the primary IVW analysis, multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the findings. The weighted median approach yielded consistent results, with an OR of 0.210 (P = 0.005), indicating reliability even when up to 50% of the genetic instruments were invalid. The MR-Egger regression analysis showed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy, as reflected by the Egger intercept (− 0.017; P = 0.545), suggesting that the causal estimates were not influenced by directional pleiotropic effects. Furthermore, the MR-PRESSO global test identified no outliers (Global test = 1.901; P = 1.000), confirming that the results were not biased by pleiotropic SNPs. Additionally, the IVW method revealed low heterogeneity across SNPs, with a Q statistic of 7.101 (P = 0.89), suggesting homogeneity of causal effects. Together, these complementary sensitivity analyses further support the validity and robustness of the causal estimates derived from the study (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4).

Mediating effects of inflammatory biomarkers and hypertension

Levels of IL10 receptor subunit beta (IL10RB) were significantly associated with both SGLT-2 inhibition and ICH. We identified a mediation effect of SGLT-2 inhibition on ICH through IL10RB, with a mediation effect value (β1 × β2) of -0.098, resulting in a mediation proportion of 9.167%. Additionally, the mediation effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on reducing ICH risk through their impact on lowering blood pressure was calculated to be -0.104, corresponding to a mediation proportion of 9.771% (Fig. 5).

IL10RB and hypertension served as mediators for the causal effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on ICH. β0, the relationship between SGLT-2 inhibitors and Intracerebral haemorrhage; β1, the relationship between SGLT-2 inhibitors and the inflammatory biomarker (hypertension), β2, the inflammatory biomarker (hypertension) to ICH, were estimated using the inverse-variance weighted approach in Mendelian randomization.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized both two-sample and two-step MR analyses to explore the relationship between SGLT-2 inhibitors, inflammatory biomarkers, and the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. Our findings suggest that SGLT-2 inhibitors may reduce ICH risk by modulating inflammatory biomarkers, with IL10RB potentially serving as a key mediator, contributing approximately 9% to the association between SGLT-2 inhibition and ICH risk.

Previous clinical trials and meta-analyses have highlighted the neuroprotective effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors, yet their role in ICH remains debated15. Our MR analysis offers causal evidence supporting a significant link between SGLT-2 inhibitors and a reduced risk of ICH. However, the exact mechanisms by which SGLT-2 inhibitors lower ICH risk and improve outcomes are still not fully elucidated. This study focuses on the anti-inflammatory pathways through which SGLT-2 inhibition may decrease ICH risk, without extensively exploring the antihypertensive effects of these inhibitors on ICH protection. Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that our findings are consistent with previous research indicating that SGLT-2 inhibition may also reduce ICH risk through blood pressure management, further strengthening the validity of our results44.

SGLT2 is primarily expressed in the microvasculature of the brain at the blood-brain barrier and in regions such as the amygdala, hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray, and dorsal medulla-nucleus tractus solitarius45. Postmortem immunoblotting studies of human brain tissue have shown a significant increase in SGLT1 and SGLT2 expression following brain injury47. ue to their lipophilic nature, SGLT-2 inhibitors are capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier, thereby directly affecting their central nervous system targets.

Deep penetrating vascular disease and small artery atherosclerosis are underlying factors in ICH, with inflammation playing a key role in atherosclerosis development19. Recent evidence suggests that SGLT-2 inhibitors can modulate inflammatory responses. Numerous animal studies have demonstrated that SGLT-2 inhibitors can slow the progression of atherosclerosis and offer anti-inflammatory benefits. These effects are achieved by reducing the expression of inflammatory markers such as Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-6, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1, Intercellular Adhesion Molecule, and Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule48. In humans, a two-year treatment with canagliflozin reduced serum IL-6 levels by 26.6% (p = 0.010). Other studies have demonstrated that canagliflozin, compared to glimepiride, lowers serum leptin and IL-6 levels in type 2 diabetes patients50. Aligned with these results, our research indi49cates that SGLT-2 inhibitors lower levels of Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), TNF, and CRP while elevating IL-10RB levels. Utilizing an extensive pQTL database, we identified significant effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors on Delta and Notch-like epidermal growth factor-related receptor (DNER), Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), CXCL9, CXCL10, Neurturin, and IL10RB. Previous studies have shown that SGLT-2 inhibitors influence IL-10 levels. For instance, patients with type 2 DM treated with empagliflozin for 24 weeks exhibited notably higher serum levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 compared to those not on SGLT-2 inhibitors. Additionally, research by Abdulrahman Mujalli et al. found that SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy substantially increased renal IL-10 concentrations, underscoring the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors in boosting IL-10 expression. Our study also demonstrated a significant positive association between SGLT-2 inhibitors and IL10RB. Moreover, we discovered a significant inverse relationship between IL10RB and ICH, with no evidence of heterogeneity or pleiotropy among the genetic instruments used51. Additionally, research by Abdulrahman Mujalli et al. found that SGLT-2 inhibitor therapy significantly increased renal IL-10 concentrations, highlighting the role of SGLT-2 inhibitors in enhancing IL-10 expression. Our study also demonstrated a significant positive association between SGLT-2 inhibitors and IL10RB. Furthermore, we identified a significant inverse relationship between IL10RB and ICH, with no evidence of heterogeneity or pleiotropy among the genetic instruments used.

IL10RB, as part of the IL-10 receptor complex, plays a crucial role in mediating IL-10 signaling, which is essential for regulating the intensity and duration of inflammatory responses52. Activation of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is a key mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10. When the IL-10 receptor pathway is activated, STAT3 is triggered, leading to the inhibition of pro-inflammatory gene transcription and effectively modulating inflammation53. Additionally, STAT3 enhances the expression of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) and Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling 354, further reducing the persistence and intensity of inflammatory responses and helping to maintain tissue homeostasis and function. IL-10 also offers substantial vascular protection by suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, thereby reducing inflammatory activity in macrophages and T cells. This action significantly lowers vascular inflammation, contributing to the prevention of atherosclerosis and other inflammation-related vascular diseases55. Moreover, through the activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway, IL-10 promotes the expression of anti-apoptotic genes, inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis, and helps maintain endothelial integrity, which is vital for vascular health and function56. Our study suggests that SGLT-2 inhibitors provide protective effects against ICH by reducing inflammatory biomarkers and regulating blood pressure. Therefore, SGLT-2 inhibitors may offer a novel therapeutic approach for high-risk ICH patients, particularly in terms of preventing or alleviating inflammatory responses and controlling blood pressure. Given that SGLT-2 inhibitors have demonstrated good safety and efficacy in diabetic patients, future research should explore their potential application in non-diabetic high-risk ICH patients.

Advantages and limitations of the study

This study represents the first investigation into the relationship between SGLT-2 inhibitors, inflammatory biomarkers, and the risk of ICH using MR analysis. MR leverages natural genetic variations to simulate randomized controlled trials, effectively addressing common issues such as confounding and reverse causation that often affect traditional observational studies. By utilizing genetic variants, MR provides a cost-effective method for causal inference without the need for additional ethical approvals.

However, there are several limitations to our research. Firstly, the study analyzed 92 biomarkers due to dataset limitations, which may not fully capture the biological mechanisms underlying the protective effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors on ICH. Future research should include broader datasets with a wider range of biomarkers and more diverse populations to better understand the full scope of biological factors involved and the therapeutic mechanisms of SGLT-2 inhibitors in ICH prevention. Secondly, while genetic variants associated with SGLT-2 inhibitors may offer a more accurate representation of lifelong exposure, they may not fully capture short-term effects. As a result, MR analysis is more suited for exploring potential causal relationships rather than quantifying precise effect sizes. Thirdly, our study relied on data from European populations, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other demographic groups. Further research is needed to assess the applicability of these results across diverse populations. Moreover, although our analysis included a broad range of inflammatory biomarkers, some relevant proteins were not covered. This highlights the need for a more comprehensive pQTL database to identify additional potential targets. Future studies should aim to expand sample sizes and include a more diverse array of racial and geographical backgrounds to enhance the validity and generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study provides genetic evidence supporting the association between SGLT-2 inhibitors, inflammatory biomarkers, and the risk of ICH. Notably, IL10RB appears to mediate the effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors on ICH risk, suggesting a potential pathway for the development of therapeutic agents aimed at offering neuroprotective benefits through this mechanism.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- SGLT2:

-

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

- MR:

-

Mendelian randomization

- GTEx:

-

Genotype-tissue expression

- HbA1c:

-

glycated hemoglobin

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- IVW:

-

Inverse variance weighted

- RAPS:

-

Robust adjusted profile score

- FDR:

-

false discovery rate

- OR:

-

odds ratios

- CIs:

-

confidence intervals

- CCL23:

-

C-C motif chemokine ligand 23

- CST5:

-

Cystatin D

- CXCL10:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10

- IL10RB:

-

IL10 receptor subunit beta

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon-gamma

- DNER:

-

Notch-like epidermal growth factor-related receptor

- LIF:

-

Leukemia inhibitory factor

- STAT3:

-

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

References

Puy, L. et al. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00424-7 (2023).

Poon, M. T., Fonville, A. F. & Al-Shahi Salman, R. Long-term prognosis after intracerebral haemorrhage: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 85, 660–667. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-306476 (2014).

Valery, L. F. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20, 795–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(21)00252-0 (2021).

Krishnamurthi, R. V. et al. The global burden of hemorrhagic stroke: A summary of findings from the GBD 2010 study. Glob. Heart 9, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.003 (2014).

Bahadar, G. A. & Shah, Z. A. Intracerebral hemorrhage and diabetes mellitus: Blood-brain barrier disruption, pathophysiology and cognitive impairments. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 20, 312–326. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871527320666210223145112 (2021).

Tun, N. N., Arunagirinathan, G., Munshi, S. K. & Pappachan, J. M. Diabetes mellitus and stroke: A clinical update. World J. Diabetes 8, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i6.235 (2017).

Jin, P. et al. Intermediate risk of cardiac events and recurrent stroke after stroke admission in young adults. Int. J. Stroke 13, 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017733929 (2018).

Zhang, G. et al. Prestroke glycemic status is associated with the functional outcome in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurol. Sci. 36, 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-014-2057-1 (2015).

Boulanger, M., Poon, M. T., Wild, S. H. & Al-Shahi Salman, R. Association between diabetes mellitus and the occurrence and outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 87, 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000003031 (2016).

Aziri, B. et al. Systematic review of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: A hopeful prospect in tackling heart failure-related events. ESC Heart Fail 10, 1499–1530. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14355 (2023).

Cannon, C. P. et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1425–1435. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2004967 (2020).

Siddiqui, Z., Hadid, S. & Frishman, W. H. SGLT-2 inhibitors: focus on dapagliflozin. Cardiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1097/crd.00000000000000694 (2024).

Bhatt, D. L. et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2030186 (2021).

Zelniker, T. A. et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial. Circulation 141, 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.119.044183 (2020).

Pawlos, A., Broncel, M., Woźniak, E. & Gorzelak-Pabiś, P. Neuroprotective effect of SGLT2 inhibitors. Molecules 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26237213 (2021).

Sato, K., Mano, T., Iwata, A. & Toda, T. Subtype-dependent reporting of stroke with SGLT2 inhibitors: Implications from a japanese pharmacovigilance study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 60, 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.1561 (2020).

Perkovic, V. et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 2295–2306. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 (2019).

Pitt, B., Steg, G., Leiter, L. A. & Bhatt, D. L. The role of combined SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibition in reducing the incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 36, 561–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-021-07291-y (2022).

Pantoni, L. Cerebral small vessel disease: From pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 9, 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(10)70104-6 (2010).

Moore, K. J., Sheedy, F. J. & Fisher, E. A. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: A dynamic balance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 709–721. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3520 (2013).

Theofilis, P. et al. The impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in rodents. Int. Immunopharmacol. 111, 109080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109080 (2022).

Emdin, C. A., Khera, A. V. & Kathiresan, S. Mendelian randomization. Jama 318, 1925–1926. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.17219 (2017).

Burgess, S., Foley, C. N., Allara, E., Staley, J. R. & Howson, J. M. M. A robust and efficient method for Mendelian randomization with hundreds of genetic variants. Nat. Commun. 11, 376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14156-4 (2020).

Sanderson, E. et al. Mendelian randomization. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-021-00092-5 (2022).

Guo, W. et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, inflammation, and heart failure: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-024-02210-5 (2024).

The GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz1776 (2020).

Võsa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300–1310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00913-z (2021).

Zuber, V. et al. Combining evidence from Mendelian randomization and colocalization: Review and comparison of approaches. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.04.001 (2022).

Bakker, M. K. et al. Anti-epileptic drug target perturbation and intracranial aneurysm risk: Mendelian randomization and colocalization study. Stroke 54, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.122.040598 (2023).

Zhao, J. H. et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat. Immunol. 24, 1540–1551. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01588-w (2023).

Said, S. et al. Genetic analysis of over half a million people characterises C-reactive protein loci. Nat. Commun. 13, 2198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29650-5 (2022).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. Bmj 362, k601. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k601 (2018).

Pierce, B. L., Ahsan, H. & Vanderweele, T. J. Power and instrument strength requirements for Mendelian randomization studies using multiple genetic variants. Int. J. Epidemiol. 40, 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq151 (2011).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8 (2023).

Burgess, S. et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: Update for summer 2023. Wellcome Open Res. 4, 186. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.1555.3 (2019).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv080 (2015).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G., Haycock, P. C. & Burgess, S. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21965 (2016).

Zhao, Q. Y., Wang, J. S., Hemani, G., Bowden, J. & Small, D. S. Statistical inference in two-sample summary-data mendelian randomization using robust adjusted profile score. Ann. Statist. 48, 1742–1769. https://doi.org/10.1214/19-aos1866 (2020).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey Smith, G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx102 (2017).

Zhao, J. et al. Bayesian weighted Mendelian randomization for causal inference based on summary statistics. Bioinformatics 36, 1501–1508. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz749 (2020).

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G. & Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 7, 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83 (2002).

Benjamini, Y., Drai, D., Elmer, G., Kafkafi, N. & Golani, I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav. Brain Res. 125, 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2 (2001).

Papadimitriou, N. et al. Physical activity and risks of breast and colorectal cancer: A Mendelian randomisation analysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 597. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14389-8 (2020).

Briasoulis, A., Al Dhaybi, O. & Bakris, G. L. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of hypertension. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 20, 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-018-0943-5 (2018).

Enerson, B. E. & Drewes, L. R. The rat blood-brain barrier transcriptome. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 26, 959–973. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600249 (2006).

Nguyen, T. et al. Dapagliflozin activates neurons in the central nervous system and regulates cardiovascular activity by inhibiting SGLT-2 in mice. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 13, 2781–2799. https://doi.org/10.2147/dmso.S258593 (2020).

Oerter, S., Förster, C. & Bohnert, M. Validation of sodium/glucose cotransporter proteins in human brain as a potential marker for temporal narrowing of the trauma formation. Int. J. Legal Med. 133, 1107–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-018-1893-6 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Impact of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors on atherosclerosis: From pharmacology to pre-clinical and clinical therapeutics. Theranostics 11, 4502–4515. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.54498 (2021).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Canagliflozin reduces inflammation and fibrosis biomarkers: A potential mechanism of action for beneficial effects of SGLT2 inhibitors in diabetic kidney disease. Diabetologia 62, 1154–1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4859-4 (2019).

Garvey, W. T. et al. Effects of canagliflozin versus glimepiride on adipokines and inflammatory biomarkers in type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 85, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2018.02.002 (2018).

Iannantuoni, F. et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin ameliorates the inflammatory profile in type 2 diabetic patients and promotes an antioxidant response in leukocytes. J. Clin. Med. 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8111814 (2019).

Ledeboer, A. et al. Expression and regulation of interleukin-10 and interleukin-10 receptor in rat astroglial and microglial cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 1175–1185. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02200.x (2002).

Murray, P. J. Understanding and exploiting the endogenous interleukin-10/STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory response. Curr. Opin Pharmacol. 6, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.010 (2006).

Yasukawa, H. et al. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 4, 551–556. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni938 (2003).

Pinderski, L. J. et al. Overexpression of interleukin-10 by activated T lymphocytes inhibits atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient Mice by altering lymphocyte and macrophage phenotypes. Circ. Res. 90, 1064–1071. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.0000018941.10726.fa (2002).

Short, W. D. et al. IL-10 promotes endothelial progenitor cell infiltration and wound healing via STAT3. FASEB J. 36, e22298. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201901024RR (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all researchers and participants who contributed and collected data.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mingsheng Huang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Methodology, Investigation. Yiheng Liu: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Cheng Chen: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was a reanalysis of previously published data and did not require ethical consent. Informed consent and ethical approval for the study of data were obtained from all participants according to the protocol of the original GWAS data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, M., Liu, Y. & Chen, C. SGLT2 inhibition mitigates intracerebral hemorrhage risk by modulating inflammation. Sci Rep 15, 17770 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84118-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84118-4