Abstract

Universal immunization of children against common vaccine-preventable diseases is crucial in reducing infant and child morbidity and mortality. Assessing the vaccination coverage is a key step to improve utilization and coverage of vaccines for under-five children. Accordingly, vaccination coverage according to the national schedule assesses the vaccination coverage of children aged 12–35 months. However, there is a scarcity of information on the full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule and its determinants in Ghana. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the prevalence and predictors of vaccination coverage according to the national schedule among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana. A cross-sectional study design using the most recent demographic and health survey data from the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey was used. We included a total weighted sample of 1,823 children aged 12–35 months in the five years preceding the survey. We used a multilevel logistic regression model to identify associated factors for vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana. The adjusted odds ratio at 95% Cl was computed to assess the strength and significance of the association between explanatory and outcome variables. Factors with a p-value of < 0.05 are declared statistically significant. In this study, the full coverage of vaccination according to the national schedule among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana was 56.45% (95% CI 51.77–56.17). Women having an ANC visit were 40% more likely (AOR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.07–1.83), women involved in healthcare decision-making were 35% more likely (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.05–1.75), Women who deliver in a health facility were 1.91 times more likely (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI 1.36–2.66), and communities with high media exposure were 47% more likely (AOR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.06–2.05) to achieve full vaccination coverage as compared to their counterparts. On the other hand, being in the Western (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.18–0.88) and Northern (AOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.74) regions decreased the odds of attaining full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana. The full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana was lower as compared to 90% coverage recommendation by World Health organization, and there is also in-equality among regions. Maternal optimal ANC contact, health facility delivery, women involved in health care decision-making, community media exposure, and region were significantly associated with full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana. To improve child immunization coverage, relevant authorities and stakeholders should work together to improve ANC visits, media exposure, facility delivery, and women’s empowerment, and attention should be given to deviant regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immunization effectively lowers mortality and morbidity in children under-five years of age and is the most economical public health intervention. It is also a fundamental component of infectious disease prevention1,2. The number of mortality among children under-five decreased sharply when the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) program was implemented, from 12.6 million in 1990 to 4.9 million in 20223. In low- and middle-income nations, a large number of children under five have been spared from deadly illnesses like polio, measles, diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and tuberculosis4,5.

Every year, vaccinations save the lives of nearly 2.5 million children under the age of five6,7. Despite this development, one-fifth of children in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) lack access to crucial lifesaving immunizations8. Because of this, almost 30 million African children under the age of five suffer from vaccine-preventable mortality, and more than 500,000 of them die annually9. To ensure that no kid is left behind, the World Health Assembly established an ambitious aim of lowering the number of unvaccinated children through the vaccination Agenda 203010. This is also included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to halt preventable deaths of infants and children under the age of five11. Sub-Saharan Africa still has the highest child and under-five mortality rates, which could be related to vaccination use12,13. Even with their demonstrated efficacy, reaching the ideal immunization rate is still difficult, especially in low- and middle-income nations like Ghana.

Various factors influence complete vaccination coverage, including access to the vaccination site, parental age and education, household income and wealth status, female child, family characteristics, parental attitude and knowledge, lack of information about vaccination schedule, and place of delivery, which were significant predictors of vaccination coverage14,15,16,17,18.

The utilization of health care services, including immunization, is a complicated issue involving health care providers, cultural attitudes, parent traits, socioeconomic considerations, and even geographic barriers19. It is well acknowledged that comprehensive vaccination coverage and the broader socioeconomic consequences of immunization were linked20. However, the benefits of immunization have not yet been realized in many African countries, including Ghana. As the coverage of full immunization among children is below the national and international target, and even not evenly distributed among geographic regions and ethnic groups, it is critical to discover the different factors that may influence being fully immunized19. In Ghana, there is a dearth of current evidence, despite the fact that vaccination coverage and related problems are becoming increasingly important global health concerns in many other nations.

Vaccination coverage can be assessed according to the national schedule21. Thus, a child aged 12–35 months is considered fully vaccinated according to the national schedule if the child has received all the basic antigens, as well as a birth dose of OPV, a birth dose of Hepatitis B vaccine, a dose of IPV, three doses of pneumococcal vaccine, two doses of Rota virus vaccine, and one dose of yellow fever vaccine in Ghana22. Timely delivery of vaccinations helps to monitor the development of vaccination use, the wise use of resources, and the timely suitable actions at the national level23.

Africa had the lowest DPT3 coverage percentage of any WHO region in 2017 (72%)24. Certain African countries have achieved higher and more stable immunization rates than their peers. Consequently, Ghana’s vaccination rates increased from 85.1% in 1998 to 95.2% in 201425. To increase vaccination coverage, it is critical to comprehend the factors that affect vaccination utilization. However, recent updates on vaccination coverage and determinants have not been reported yet in Ghana. Therefore, this study aimed to update the prevalence and predictor of vaccination coverage among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana, which will provide important information for concerned bodies to strengthen positive efforts and avoid disabling factors to achieve WHO recommended vaccination coverage.

Method and materials

Study setting

The study setting is the Republic of Ghana. The Republic of Ghana is one of the countries in West Africa and has a total area of 238,533 square kilometers26. Its borders are to the north with Burkina Faso, to the east with Togo, to the south by the Atlantic Ocean, and to the west with Côte d’Ivoire. The nation currently consists of 16 regions. The following 16 regions constitute Ghana: Greater Accra area, Central, Eastern, Upper East, Upper West, Volta, Northern, and Ashanti. The other regions include Brong, Oti, Ahafo, Bono East, North East, Savannah, Western North, and Western.

Data source and sampling procedure

This study was done using the data extracted from the standard Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2022. The data was collected from October 2022 to January 2023, and it is the seventh DHS series. This study used the most recent DHS data set. Every five years, nationwide surveys known as the DHS are conducted worldwide in low- and middle-income nations. Data were collected from a national representative sample of approximately 18,450 households from all 16 regions in Ghana. The sampling procedure used in the 2022 GDHS was stratified two-stage cluster sampling, designed to yield representative results at the national level in urban and rural areas and for most DHS indicators in each country’s region.

In the first stage, 618 targeted clusters were selected from the sampling frame using a probability-proportional-to-size strategy for urban and rural areas in each region. Then the number of targeted clusters was selected with equal probability through systematic random sampling of the clusters selected in the first phase for urban and rural areas.

In the second stage, after the selection of clusters, a household listing and map updating were carried out in all of the selected clusters to develop a list of households for each cluster. The list served as a sampling frame for the household sample. A fixed number of 30 households in each cluster were randomly selected from the list for interviews. Thus, 17,993 households were successfully interviewed in 618 clusters. For this study, women who had given a birth within five years before the surveys were included. For mothers having more than two kids aged 12–35 months, the last birth was included and analyzed for the study27.

Inclusion criteria

All children aged 12–35 months preceding the survey years in the selected EAs who were in the study area were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Children in the age category of 12–35 months who had an incomplete vaccination card and had a missing value for the outcome variables were excluded. In addition, if more than two children aged 12–35 months available in the household, only the recent birth included in the study and other children were excluded.

Source population

The source population was all children aged 12–35 months, five years preceding the survey period in Ghana.

Study population

The study population consisted of children aged 12–35 months preceding the five-year survey period in the selected enumeration areas, which are the primary sampling units of the survey cluster. The mother or caregiver was interviewed for the survey in the country, and mothers who had more than one child during the survey period were asked about the most recent child.

Study variables

Outcome of variable

The outcome variable in this study was the probability of the last child aged 12–35 months being fully vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule of Ghana. It was assessed by the interview responses from mothers and the immunization card report. According to Ghana national vaccination schedule a child aged 12–35 month should receive all the basic antigens, birth dose of OPV, a birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine, a dose of IPV, three doses of the pneumococcal vaccine, two doses of the rotavirus vaccine, one dose of the yellow fever vaccine, a second dose of the measles-rubella vaccine, and a dose of the meningitis vaccine. To estimate the proportion of fully vaccinated children, we created a composite variable for children who had received all of these vaccines from the age of 12–35 months. For the above vaccines the responses were “yes, incomplete, and no”. Then we created a new composite variable and recoded it as “Yes = 1” for children who responded yes for the above vaccines, considered “fully vaccinated,” and otherwise as “No = 0” for children who responded as no and had an incomplete response for the above vaccine, considered “not fully vaccinated.”

Independent variables

Both individual and community-level factors were reviewed from different literatures, and these include child age and sex, maternal education, working status and educational status, parent (husband) education and employment status, ANC visit, media exposure, place of delivery, number of under-five children, household head sex, wealth index, birth order, PNC visit, and mothers involvement in household decision-making. Whereas, whether distance to a health facility is a problem or not, residence, region, community women’s illiteracy level, community poverty level, and community media exposure were community-level variables aggregated from individual-level factors.

The wealth index was re-categorized as poor, middle, and rich28, but available in poorest, poor, middle, rich and richest quintile in DHS data set.

ANC was classified as optimal if a mother had more than eight visits during her pregnancy29. Maternal education status was categorized as no formal education, primary, secondary, and higher in our study and other EDHS30. Reading newspapers, watching television, and listening to the radio were three ways that media exposure was computed. When there was exposure to any of the three, these variables were combined and classified as yes, meaning that reading newspapers, listening to the radio, or watching television were present31.

Mother’s involvement in decision-making was aggregated from variables: decision on purchasing large household purchases, decision on husband’s earning, decision on respondent’s earning, and decision on health care, which is categorized as yes if the mother is involved in the above decision-making and no if she is not involved in the above category.

Data management

After being extracted from the GDHS portal, Stata version 14 was used to enter, code, clean, record, and analyze the data. Stata was initially developed by the Computing Resource Center in California.

Model selection

In DHS, data variables are nested by clusters, and those within the same cluster show more similarities than those with separate clusters. Thus, using the traditional logistic regression model violates the assumptions of independent observation and equal variance across clusters. Therefore, a multi-level logistic regression analysis was employed in this study in order to account for the hierarchical nature of DHS data.

Fixed effect analysis (measure of association)

A bivariate multi-level logistic regression model was employed in the study to identify the variables associated with vaccination coverage. In the analysis, four models were fitted. The first (null) model contains only the outcome variables to test random variability and estimate the intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC). The second model contains individual-level variables; the third model contains only community-level variables; and the fourth model contains both individual-level and community-level variables32. A p-value of 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. Adjusted odds ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to identify independent predictors of vaccination coverage.

Hence the log of probability of attaining vaccination coverage was modeled using a two level multilevel by using the Stata syntax xtmelogit33.

logit (πij) = log [πij/ (1 − πij)] = β0 + β1xij + β2xij … +u0j + e0ij,

where, πij: the probability of the ith young children receiving full vaccination, (1 − πij), the probability of young children not receiving full vaccination, β0: intercept, βn: regression coefficient Xij: independent variables u0j: community level error, e0ij: individual level errors34.

Random effect analysis (measure of association)

Variation of the outcome variable or random effects was assessed using the proportional change in variance (PCV), intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), and median odds ratio (MOR)35,36.

The ICC shows the variation in attainment of full vaccination coverage due to community characteristics, which was calculated as: ICC = σ2/(σ2 + π2/3), where σ2 is the variance of the cluster37.

The higher the ICC, the more relevant the community characteristics are for understanding individual variation in the attainment of full vaccination coverage.

MOR is the median value of the odds ratio between the areas with the highest vaccination coverage and the area with the lowest attainment of vaccination coverage when randomly picking out two younger children from two clusters, which was calculated as: MOR = \(e\:0.95\surd{\sigma^{2}}\) where σ2 is the variance of the cluster. In this study, MOR shows the extent to which the individual probability of attainment of vaccination coverage is determined by the residential area38.

Furthermore, the PCV illustrates how different factors account for variations in the attainment of full vaccination coverage and is computed as PCV=(Vnull-Vcluster)/ Vnull, where Vcluster is the cluster-level variance and Vnull is the variance of the null model39.

The likelihood of attainment full vaccination coverage and independent variables at the individual and community levels were estimated using both fixed effects and random effect analysis. Due to the hierarchical nature of the model, models were compared using deviation = −2 (log likelihood ratio), and the best-fit model was determined by taking the model with the lowest deviance. By calculating the variance inflation factors (VIF), the variables employed in the models were checked for multi-collinearity; the results were within acceptable ranges of one to ten40.

Ethics statement and consent to participate

The authors analyzed secondary, publicly available data obtained from the DHS program database. There was no additional ethical approval, and informed consent was obtained by the authors. In order to perform our study, we registered with the DHS web archive, requested the dataset, and were granted permission to access and download the data files. According to the DHS report, all participant data was anonymized during the collection of the survey data. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available online at http://www.dhsprogram.com.

Result

This study was conducted among a weighted sample of 1823 women-child pairs aged 12–35 months in Ghana. The mean age of children was 17.41 ± 0.05 months, and the mean age of mothers was 29.74 ± 0.05 years. More than two-thirds (70. 26% and 60.34%) of mothers were aged 20–34 years and were married, respectively. Nearly two-thirds (69.06%) of households were headed by men. Nearly half (45.2%) of households were poor, and more than one-third (40.54) of mothers had an ANC visit during their pregnancy. The majority (86.01%) of children’s were delivered at health facilities. Majority (82.94%) of women had media exposure. Three-fourth (74.96%) of women were involved in household healthcare decision-making. Nearly half (47.06%) of women’s were residing in the urban areas. One-third (74.72%) of women’s had no difficulty accessing health facilities. More than two-third (68.78%) of the community had high media exposure. One-fourth (24.8%) of mothers had a high community illiteracy level (Table 1).

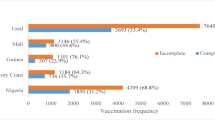

The prevalence of full vaccination coverage according to national schedule

The prevalence of full vaccination coverage according to national schedule among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana was 56.45 (95% CI 51.77–56.17). (Fig. 1)

Regional prevalence of vaccination coverage

The highest prevalence of vaccination coverage among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana was observed in greater Accra (71.99%), and the lowest prevalence was observed in the northern region (31.18%). There is a disparity in vaccination coverage among children aged 12–35 months in Ghanaian regions; therefore, special attention could be given to the northern region. (Fig. 2)

Random effect and model fit statistics

The null model was run to determine whether the data supported assessing randomness at the community level. The ICC value in the null model indicates 20.91% of the attainment of vaccination coverage was due to the difference between clusters. In the null model, the odds of attainment of vaccination coverage were 2.43 times variable between high and low clusters (heterogeneous among clusters). Regarding the final model PCV, about 70.11% of the variability in attainment of vaccination coverage was attributed to both individual and community-level factors. Model IV was selected as the best-fitting model since it had the lowest deviance (Table 2).

Factors associated with full vaccination coverage among children aged 12–35 in Ghana

In the final model (model III) of multivariable multilevel logistic regression, child age, wealth index, male household head sex, currently breastfeeding and Savannah region were significantly associated with attainment of the minimum acceptable among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana.

Accordingly, women who had an ANC visit were 40% more likely (AOR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.07–1.83) to have vaccinated their children as compared to women who had no optimal ANC visit. Women involved in household health care decision-making were 35% more likely (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.05–1.75) to attain vaccination coverage as compared to women who did not involve themselves in household health care decision-making. Women who deliver in a health facility were 91% more likely (AOR = 1.91, 95% CI 1.36–2.66) to attain full vaccination coverage as compared to women who deliver at home. Communities with high media exposure were 47% more likely (AOR = 1.47, 95% CI 1.06–2.05) to achieve full vaccination coverage as compared to communities with low media exposure. On the other hand, children residing in the Western region of Ghana had 60% (AOR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.18–0.88) less likely to have vaccination coverage as compared to children residing in the Greater Accra region. Similarly, children residing in Northern regions of Ghana had 67% less likely (AOR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.74) to have vaccination coverage as compared to children residing in the Greater Accra region (Table 3).

Discussion

Immunization effectively lowers mortality and morbidity in children under five years old and is a cornerstone of infectious disease prevention. Vaccination coverage has increased dramatically in various African countries in recent decades41. To meet the Global Vaccine Action Plan target of 90% child vaccination coverage, it is critical to determine the magnitude based on recent statistics and identify enabling and disabling factors in low- and middle-income countries.

This study finding is lower than sub-Saharan African study (59.4%)42, Malaysia (86.4%)43, India (71%)44. However, This study finding is higher than study done in Afghanistan (45.7%)45, Ethiopia (31.9%)46. The potential explanation for this discrepancy may be due to the presence of health infrastructure, variations in policies against immunization services, variability in awareness of immunization services, and socio-cultural differences. Furthermore, time intervals between study periods may induce variations on the extent of coverage; recent studies may yield greater coverage, whereas remote studies may reveal less coverage.

The multi-level multivariable logistic regression model revealed that maternal optimal ANC contact, health facility delivery, women involved in health care decision-making, community media exposure, and region were significantly associated with full vaccination coverage.

Children born at health facility had higher chance of attaining vaccination coverage as compared to children born home. This is supported by studies done in different parts of the world47,48,49,50,51,52,53. One explanation might be that a mother giving birth in a medical facility has a higher chance of receiving instruction from medical personnel regarding the importance of vaccination. In addition, upon discharge from a medical facility, newborns received their first doses of the BCG, polio, and hepatitis B vaccines54,55. But some women are not well-informed about the recommended immunization regimen or the significance of booster doses56. This is why health care providers need to proactively educate parents about the immunizations that are advised for every child.

Children born to mothers who attended optimal antenatal care during pregnancy were more likely to be fully immunized55,57,58. One possible explanation is that during an ANC visit, mothers will obtain enough positive information regarding childhood vaccination to make them secure in their child’s preventative health. Furthermore, during an ANC visit, mothers acquire enough positive information regarding childhood vaccinations to feel confident in their child’s preventative health. Furthermore, mothers who visited health facilities throughout their pregnancy may have received counseling on kid immunization, with the need of timely childhood immunization uptake being stressed on a consistent basis. Antenatal care programs typically give information regarding children’s care, including the scheduling and importance of immunization for children52. Therefore, optimizing optimal ANC use shall be strengthened to improve the coverage of vaccination in children.

Community media exposure is another factor associated with full childhood vaccination. This supported by studies done in Ethiopia48, Zimbabwe51, East Africa59 and SSA7. This is due to the media’s dissemination of vaccination use information, schedules, and campaigns. Furthermore, media could induce behavioral changes, allowing for the adoption of certain behaviors48. Furthermore, media exposure is the most effective health promotion tool to readily access the community and promote health-seeking behavior60.

In line with other studies, women who had autonomy in making household decisions were more likely to attain full vaccination coverage as compared to women who did not participate in household health care decision-making61. This is because mothers’ concerns about their children’s health care and vaccination use are sparked by their autonomy in making decisions and their awareness of their own health62. Therefore, it could be beneficial for parents to learn about their child’s immunization through community-based behavior modification programs.

The Northern and Western region of Ghana had lower vaccination coverage as compared to Greater Ghana regions. The possible explanation could be these regions were extreme rural, deep poverty and remoteness63. Furthermore, northern Ghana has a vaccination scarcity, poor health infrastructure, low public awareness, and insufficient surveillance and monitoring64.

Ghana’s government must be more resolute in its support of the WHO’s 2030 immunization agenda, which calls for universal access to vaccines for the promotion of health and wellbeing at all ages, everywhere65. Furthermore, in order to build an integrated, all-inclusive immunization program in Ghana, priorities for implementation must be established.

Strength and limitation

The findings of this study were not without limitations and should be noted. First, the analysis was conducted using potential predictor variables extracted from GDHS. But variable other than those mentioned in the DHS data set would also be likely to be important determinates of full immunization among children aged 12–35 months. Some of these include the distance to immunization centers and the quality of immunization services. Secondly, information on child immunization was reported retrospectively using maternal verbal responses and immunization cards; thus, it is highly susceptible to recall bias. Thirdly, the analysis was conducted using data collected in a cross-sectional survey that causes an egg-chicken dilemma or cause-and effect relationship. Furthermore, as DHS guide recommendations, a vaccinated child might be considered unvaccinated if the child didn’t have a vaccination card or the mother was not available to answer for the vaccination status of the child; therefore, it introduces bias and leads to underestimation or overestimation of vaccination coverage.

Therefore, to ensure validity, longitudinally collected data at different times should be used.

Conclusion

The full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana was lower as compared to 90% coverage by world health organization recommendation, and there is also inequality among regions. Maternal optimal ANC contact, health facility delivery, women involved in health care decision-making, community media exposure, and region were significantly associated with full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule in Ghana. Therefore, public health programs target emerging or deviant regions. By enhancing ANC visits, media exposure, facility delivery, and empowering women, the relevant authorities and stakeholders should work properly to increase child immunization coverage.

Data availability

The most recent data from the Demographic and Health Survey were used in this study, and it is publically available online at (http://www.dhsprogram.com). The datasets used and/ or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Maman, K. et al. The value of childhood combination vaccines: from beliefs to evidence. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 11(9), 2132–2141 (2015).

Ashish, K., Nelin, V., Raaijmakers, H., Kim, H. J., Singh, C. & Målqvist, M. Increased immunization coverage addresses the equity gap in Nepal. Bull. World Health Organ. 95(4), 261 (2017).

WHO. Child mortality and causes of death. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/child-mortality-and-causes-of-death (2024).

Kretsinger, K. et al. Polio eradication in the World Health Organization African Region, 2008–2012. J. Infect. Dis. 210(suppl_1), S23–S39 (2014).

Waziri, N. E. et al. Polio eradication in Nigeria and the role of the National Stop Transmission of Polio program, 2012–2013. J. Infect. Dis. 210(suppl_1), S111–S117 (2014).

Antai, D. Inequitable childhood immunization uptake in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis of individual and contextual determinants. BMC Infect. Dis. 9, 1–10 (2009).

Wiysonge, C. S., Uthman, O. A. & Ndumbe, P. M. Individual and contextual factors associated with low childhood immunisation coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One 7(5), e37905 (2012).

Ozigbu, C. E., Olatosi, B., Li, Z., Hardin, J. W. & Hair, N. L. J. V. Correlates of zero-dose vaccination status among children aged 12–59 months in Sub-saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. Vaccines 10(7), 1052 (2022).

World Health Organization. Regional strategic plan for immunization 2014–2020 (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa, 2015).

Lindstrand, A. et al. Implementing the immunization agenda 2030: A framework for action through coordinated planning, monitoring & evaluation, ownership & accountability, and communications & advocacy. Vaccine 42(suppl 1), S15–S27 (2024).

Krannich, A.-L. & Reiser, D. The United Nations sustainable development goals 2030. In Encyclopedia of Sustainable Management 1–5 (Springer, 2021).

Olusegun, O. L. & Ibe, R. T. Curbing maternal and child mortality: The Nigerian experience. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 4(3), 33–39 (2012).

Hug, L., Alexander, M., You, D. & Alkema, L. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis. Lencet Glob. Health 7(6), e710–e720 (2019).

Jani, J. V. et al. Risk factors for incomplete vaccination and missed opportunity for immunization in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health 8, 161 (2008).

Mitchell, S. et al. Equity and vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of measles vaccination in Lasbela District, Pakistan. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 9, S7 (2009).

Mutua, M. K., Kimani-Murage, E. & Ettarh, R. R. Childhood vaccination in informal urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya: who gets vaccinated?. BMC Public Health 11, 1–11 (2011).

Pande, R. P. & Yazbeck, A. S. What’s in a country average? Wealth, gender, and regional inequalities in immunization in India. Soc. Sci. Med. 57(11), 2075–2088 (2003).

Canavan, M. E. et al. Correlates of complete childhood vaccination in East African countries. PLoS One 9(4), e95709 (2014).

Andersen, R. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav., 1–10 (1995).

Rodrigues, C. M. & Plotkin, S. A. Impact of vaccines; health, economic and social perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1526 (2020).

https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR387-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm

Soares, M. M. et al. Prevalence of processed and ultra-processed food intake in Brazilian children (6–24 months) is associated with maternal consumption and breastfeeding practices. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 72(7), 978–988 (2021).

https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=25790&lid

World Health Organization. Global vaccine action plan 2011–2020 (2013).

Budu, E., Darteh, E. K. M., Ahinkorah, B. O., Seidu, A.-A. & Dickson, K. S. Trend and determinants of complete vaccination coverage among children aged 12–23 months in Ghana: analysis of data from the 1998 to 2014 Ghana demographic and health surveys. PLos One 15(10), e0239754 (2020).

Ghana Statistics Service. 2010 Population and Housing Census: National Analytical Report (Ghana Statistics Service, 2013).

Gipson, J. D., Koenig, M. A. & Hindin, M. J. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud. Fam. Plann. 39(1), 18–38 (2008).

Bitew, F. H. Spatio-temporal Inequalities and Predictive Models for Determinants of Undernutrition Among Women and Children in Ethiopia (The University of Texas at San Antonio, 2020).

World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: screening, diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis disease in pregnant women. Evidence-to-action brief: Highlights and key messages from the World Health Organization’s 2016 global recommendations (World Health Organization, 2023).

Anyamele, O. D., Ukawuilulu, J. O. & Akanegbu, B. N. The role of wealth and Mother’s education in infant and child mortality in 26 sub-Saharan African countries: evidence from pooled demographic and health survey (DHS) data 2003–2011 and African development indicators (ADI), 2012. Soc. Indic. Res. 130, 1125–1146 (2017).

Seidu, A.-A. et al. Mass media exposure and women’s household decision-making capacity in 30 sub-Saharan African countries: Analysis of demographic and health surveys. Front. Psychol. 11, 581614 (2020).

Sommet, N. & Morselli, D. Keep calm and learn multilevel logistic modeling: a simplified three-step procedure using Stata, R, mplus, and SPSS. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 30, 203–218 (2017).

Goldstein, H. Multilevel Statistical Models (Wiley, 2011).

Snijders, T. A. & Bosker, R. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling (SAGE, 2011).

Penny, W. & Holmes, A. J. Random Effects Analysis 156–165 (Elsevier, 2007).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1(2), 97–111 (2010).

Rodriguez, G. & Elo, I. Intra-class correlation in random-effects models for binary data. Stata J. 3(1), 32–46 (2003).

Merlo, J. et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60(4), 290–297 (2006).

Tesema, G. A. et al. Individual and community-level determinants, and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia, 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. PLoS One 15(11), e0242242 (2020).

O’brien, R. M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41, 673–690 (2007).

Ali, H. A. et al. Vaccine equity in low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 21(1), 82 (2022).

Fenta, S. M. et al. Determinants of full childhood immunization among children aged 12–23 months in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis using Demographic and Health Survey Data. Trop. Med. Health 49, 1–12 (2021).

Lim, K. et al. Complete immunization coverage and its determinants among children in Malaysia: findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2016. Public Health 153, 52–57 (2017).

Francis, M. R. et al. Vaccination coverage and factors associated with routine childhood vaccination uptake in rural Vellore, southern India, 2017. Vaccine 37(23), 3078–3087 (2019).

Aalemi, A. K. et al. Factors influencing vaccination coverage among children age 12–23 months in Afghanistan: Analysis of the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS One 15(8), e0236955 (2020).

Mekonnen, Z. A. et al. Timely completion of vaccination and its determinants among children in northwest, Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 20, 1–13 (2020).

Tamirat, K. S. & Sisay, M. M. Full immunization coverage and its associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in Ethiopia: further analysis from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 19, 1–7 (2019).

Abadura, S. A., Lerebo, W. T., Kulkarni, U. & Mekonnen, Z. A. Individual and community level determinants of childhood full immunization in Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 15, 1–10 (2015).

Jama, A. A. Determinants of complete immunization coverage among children aged 11–24 months in Somalia. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020(1), 5827074 (2020).

Acharya, P., Kismul, H., Mapatano, M. A. & Hatløy, A. J. Individual-and community-level determinants of child immunization in the Democratic Republic of Congo: a multilevel analysis. PLoS One 13(8), e0202742 (2018).

Mukungwa, T. Factors associated with full immunization coverage amongst children aged 12–23 months in Zimbabwe. Afr. Popul. Stud. 29(2) (2015).

Efendi, F. et al. Factors associated with complete immunizations coverage among Indonesian children aged 12–23 months. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 108, 104651 (2020).

Sarker, A. R., Akram, R., Ali, N., Chowdhury, Z. I. & Sultana, M. J. M. Coverage and determinants of full immunization: vaccination coverage among Senegalese children. Medicine 55(8), 480 (2019).

Adedire, E. B. et al. Immunisation coverage and its determinants among children aged 12–23 months in Atakumosa-west district, Osun State Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 16, 1–8 (2016).

Travassos, M. A. et al. Strategies for coordination of a serosurvey in parallel with an immunization coverage survey. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 93(2), 416 (2015).

Kusnanto, K., Ulfiana, E. & Hadarani, M. J. J. N. Behavior of family in practice hepatitis b immunization at baby 0–7 days old. J. NERS 3(2), 151–156 (2017).

Nozaki, I. et al. Factors influencing basic vaccination coverage in Myanmar: secondary analysis of 2015 Myanmar demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health 2019(19), 1–8 (2015).

Russo, G. et al. Vaccine coverage and determinants of incomplete vaccination in children aged 12–23 months in Dschang, West Region, Cameroon: a cross-sectional survey during a polio outbreak. BMC Public Health 15, 1–11 (2015).

Tesema, G. A., Tessema, Z. T., Tamirat, K. S. & Teshale, A. B. Complete basic childhood vaccination and associated factors among children aged 12–23 months in East Africa: a multilevel analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 20, 1–14 (2020).

Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 15(3), 259–267 (2000).

Herliana, P. & Douiri, A. Determinants of immunisation coverage of children aged 12–59 months in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 7(12), e015790 (2017).

Adeyanju, G. C. & Betsch, C. Immunotherapeutics. Vaccination decision-making among mothers of children 0–12 months old in Nigeria: A qualitative study. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 20(1), 2355709 (2024).

Vaccination, K. P. Complete child immunization: a cluster analysis of positive deviant regions in Ghana. J. Vaccines Vaccin. 8(1), 1–7 (2017).

Asumah, M. N. et al. Measles outbreak in Northern Ghana highlights vaccine shortage crisis. New Microbes Infect. 53, 101124 (2023).

Agenda WI. 2030: A global strategy to leave no one behind; 2020 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to MEASURE DHS for providing us with the data for free online.

Funding

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Berhan Tekeba: made conceptualization, drafted the original manuscript, and software analysis.Tadesse Tarik Tamir: made supervision and methodlogy. Alebachew Ferede Zegeye: checked the analysis and made substantial contributions in reviewing the design of the study and the draft manuscript edits and review abstract. He critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and contributed to the final approval of the version to be submitted. All listed authors have approved the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tekeba, B., Tamir, T.T. & Zegeye, A.F. Prevalence and determinants of full vaccination coverage according to the national schedule among children aged 12–35 months in Ghana. Sci Rep 15, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84481-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84481-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Political economy of vaccine distribution and acceptance in Nigeria: critical analysis of global health interventions and local realities

Discover Public Health (2025)

-

Propensity score matching analysis of the effect of four or more antenatal care visits on basic childhood immunization in Ethiopia

Scientific Reports (2025)