Abstract

Mechanical properties of steels are closely related to microstructures. However, in steel process there is a lack of effective online monitoring and characterized methods for steel microstructures and mechanical properties, giving rise to issues of low steel quality and high alloy costs (to ensure mechanical strength). In order to ensure the mechanical performance of steels, advanced characterization methods and measurement instruments are necessary for real-time online monitoring of the production process. In this study, electromagnetic responses on steel microstructures and mechanical properties are investigated. An online electromagnetic non-destructive characterization system for steel microstructures is developed. Relationships between microstructures and steel mechanical properties have been demonstrated through mechanical performance tests. Therefore, the electromagnetic non-destructive characterization system can be used for real-time online monitoring of mechanical properties of steels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Steels continue to dominate as the primary structural materials in the present and the foreseeable future, serving as the material basis for social and economic development1,2,3,4. Carbon steels, such as Q235 (GB/T 700-2006)5,6,7, Q355B (GB/T 1591-2018)8,9,10 are extensively utilized due to the excellent mechanical performance and the cost-effectiveness. Steel microstructures determine mechanical properties and product service life11. It is required real-time online monitoring and adjustment for phase compositions and mechanical properties during the steel production process. Rapid and accurate characterization on steel microstructural components, e.g. phase type, phase fraction, phase distribution, grain size, is an important precondition for achieving quantitative adjust of steel microstructures. Multi-frequency electromagnetic sensors can be deployed in steel product process and are able to give information of microstructure transformation online12, as shown in Fig. 1. Production control therefore can receive the feedback in real time and dynamically adjust production parameters to guarantee desirable steel microstructures and mechanical properties.

However, current research of characterization on steel microstructures and mechanical properties is confined to the stages of temperature measurements and finite element modellings, without widespread application in industrial practice13. Various environmental influences and the effects of measurement parameters during industrial measurements have yet to be thoroughly investigated from an academic perspective.

Multi-frequency electromagnetic technology, based on electromagnetic induction, is highly valued for its real-time, online capabilities, which suits the detection needs in steel production. Shen14 demonstrated that as the ferrite phase fraction increases in dual-phase steel (ferrite-pearlite), its relative permeability rises. This study used multi-frequency sensors to monitor phase transformations during rolling and adjusted cooling systems dynamically for cost-effective advanced steel production. Davis15 showed that these sensors can detect microstructural changes in steel, with low-frequency inductance measuring ferrite in samples with less than 40% ferrite and zero-crossing frequency characterizing ferrite content above 40%. The finite element (FE) method investigated sensor responses to steel microstructure changes. Xiao16 used a microstructure FE model to calculate magnetic permeability based on various phase compositions and grain sizes. Yanagawa17 found that ferrite-pearlite yield strength varies with pearlite fraction, from 0.354 GPa to 0.364 GPa. Jolfaei18 used sensors to relate magnetic permeability and tensile strength in dual-phase steel, showing significant impacts from ferrite fraction and grain size. Wilson Handoko19 identified martensite as the hardest phase, followed by bainite, pearlite, and ferrite, with hardness increasing with pearlite content. Trivedi20 found that increasing ferrite content decreases tensile properties and hardness but increases toughness, while pearlite increases tensile properties and hardness but decreases toughness. Ayush21 found that heat treatment can improve the toughness of materials. Kulkarni22 found that different heat treatment techniques can enhance the mechanical properties of steel samples, such as tensile strength, hardness, toughness and shear strength.

Current studies are carried out based on the fact that there are limited relationships between electromagnetic signals and steel microstructures/mechanical properties. Most researches are limited to investigate influences of microstructures on mechanical properties. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between electromagnetic signals and mechanical properties. In addition, steel production sites characterized by high temperatures, extensive noise and dust. Some possessed large mechanical facilities will give limited space for the electromagnetic sensor installation. The challenge lies in the development of measurement system with stable performance and the proper installation of sensors to achieve real-time online monitoring without disrupting production processes.

In the continuous steel product process, the key to accurately characterize mechanical properties lies in establishing relationships between electromagnetic signals and steel microstructure components. This paper utilized multi-frequency electromagnetic sensor technology to study responses of steel microstructures (Q235 and Q355B) on electromagnetic signals. The quantitative relationships between electromagnetic signals and microstructures were investigated. Furthermore, relationships between microstructure and material properties such as strength, hardness and toughness were explained. The mechanism by which dislocations affect the mechanical properties of the material was studied from an atomic perspective.

Principle of multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization technology

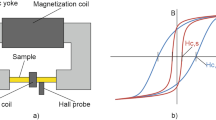

The multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization technology is based on the principle of electromagnetic induction. The finite element modeling of the magnetic induction mechanism is shown in Fig. 2a. It shows the current direction of the excitation coil and induction coil, represented by yellow and green arrows respectively. Magnetic induction lines move from one yoke foot to another through the steel, resulting in a higher magnetic flux density in this part of the sample, while the other areas of the steel have a lower magnetic flux density.

Experimental results demonstrate that inductive reactance is directly proportional to frequency. If inductive reactance is denoted as (XL), inductance as (L) and frequency as (f), then the calculation formula is:

As frequency increases, the magnetic field changes more rapidly. This implies a greater rate of change in the magnetic field over time. According to Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction, the induced electromotive force (EMF) increases with frequency. The increased EMF generates stronger eddy currents within the steel conductor. These eddy currents, in turn, produce magnetic fields in the opposite direction to the changing magnetic field, leading to greater energy losses and localized heating effects. Studies have shown that eddy currents increase with frequency, eventually approaching the strength of the original magnetic field, thus reaching a dynamic equilibrium.

At lower frequencies, the magnetic field generated by the excitation coil magnetizes the steel sample and the inductive reactance signal is primarily influenced by frequency. When the frequency and the effects of eddy currents reach a balance, the inductive reactance value reaches to the peak. With the further increase in frequency, the alternating magnetic field induces more eddy currents. The magnetic field generated by the eddy currents opposes the primary magnetic field, reducing the inductance of the sensing coil and thus lowering the inductive reactance value. At this stage, eddy currents become the main factor affecting the inductive reactance signal. The signal is predominantly influenced by eddy currents. When the intensity of the eddy currents eventually approaches the strength of the original magnetic field, the inductive reactance value reaches its lowest point. The change of the inductive reactance strength with frequency is shown in Fig. 2b.

Development of the multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization system

A U-shaped electromagnetic sensor is used in the study. It generally consists of a yoke (the shape and size can be determined based on the object being tested), excitation coil, induction coil, signal amplification and recognition system with electronic circuit connection. The yoke is made of the soft ferrite material with an overall height of 80 mm and a length of 134 mm. The schematic diagram of the U-shaped sensor is shown in Fig. 3a. The U-shaped sensor is wound with 0.5 mm silver-core wire. The excitation coil in the middle of the yoke is wound in a stacked manner, with 50 turns per layer and a total of 150 turns. Each of the two induction coils consists of 50 turns of wire. The dimensions of the U-shaped sensor are as shown in Fig. 3b.

Due to the harsh operating environment in the production site, protective enclosures were designed to reduce the impact of the steel production site and to extend the lifespan for the sensor, as shown in Fig. 3c. The enclosure is made of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) material, which are capable of both dust and moisture resistance, as well as 250 ℃ temperature endurance. To better shield the U-shaped sensor from the effects of on-site environments, a layer of insulating tape is wrapped inside the sensors.

The Multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization hardware system consists of enhanced multi-frequency single-channel digital electromagnetic measurement instrument and the sensor. The hardware system is illustrated in Fig. 3e. The hardware design comprises three main functional modules: the Signal Generator Module (SGM), Impedance Measurement Module (IMM) and High-Speed Universal Serial Bus (USB). The IMM is used to measure the excitation current and detected voltage waveforms, with the excitation current generated by the SGM. The measurement results are sent back to the host via a high-speed USB link.

The operation software was built on the LabVIEW platform and is designed to display the inductive reactance values detected by sensors within the range of 1–65,000 Hz. It enables online output of frequency and inductive reactance curves with a sampling interval of 0.2 s under corresponding steel production parameters.

The parameter setting interface includes the required product information, measurement setting and real-time displayed data. The input data includes the measurement frequency (ranging from 1 Hz to 65,000 Hz), test speed Cascaded Integrator-Comb Filter (CIC), lift-off (distance between the sensor and the sample), steel moving speed and sample geometry information. The measurement results include the phase fraction of the microstructure, strength, hardness and toughness. Based on the varying lift-off distances at the installation site, constant values K and C are set to adjust the measurement signal range, implementing the functionality of measuring signal × K + C, with default values of 1 and 0 respectively. The test speed CIC (CIC × 1000/ F = sampling interval) is used to adjust the speed of signal data processing. The software operating interface is shown in Fig. 3f.

The magnetic permeability of ferrite is superior to pearlite for steel microstructures. The ferrite phase fraction is the primary influencing factor on the detection signal of the electromagnetic sensor. By establishing a database of the relationship between inductive reactance and ferrite phase fraction, a database of the relationship between ferrite phase fraction and mechanical properties, the relationship between inductive reactance signal and mechanical properties can be derived. The summarized database is input into the multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization system, which is eventually applied in the industrial production. The on-site production installation position is shown in Fig. 3g. The complete process of multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization system is shown in Fig. 3d.

Results

Metallographic analysis

This study conducted metallographic structure and grain size analyses on Q235B and Q355B samples obtained from the production. Figure 4a shows the multi frequency electromagnetic characterization system used for Q235 samples in the lab. The chemical compositions of samples are listed in Table 1.

Figure 4b shows the metallographic structures of Q235 and Q355 samples. The microstructures of all samples are observed to consist of ferrite (white) and pearlite (black). The phase fraction of ferrite was determined using ImageJ software and the area fraction method, as depicted in Fig. 4c. The ferrite phase fraction for each sample was obtained by averaging phase fractions of ferrite from six different faces of the sample. The complete 3D metallographic structure of the sample is shown in Fig. 4d. A grain size analysis was conducted on samples, as shown in Fig. 4e. The results of the grain size levels are listed in Table 2, indicating that the grain sizes of the samples are generally similar and the influence on the electromagnetic signal can be omitted.

Impacts of microstructures on magnetic induction intensity

The influence of ferrite phase fraction on electromagnetic signals can be explained by establishing a microstructure finite element model12,13,15 with the induced magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 5a. Figure 5a–c illustrate the magnetic flux density distribution in the ferrite-pearlite dual-phase structure with ferrite contents ranging from 65 to 85%. Red regions represent ferrite grains with high magnetic flux density, while blue regions is pearlite grains with low magnetic flux density. Some ferrite grains encapsulated by pearlite are shown in yellow or cyan. Due to the obstruction effect to the flowing of magnetic flux lines by pearlite, grains perpendicular to the flow direction of the magnetic flux lines exhibit lower magnetic flux density, shown as green in Fig. 5a. The result indicates that as the ferrite content increases, the magnetic flux density also increases. This gives a decrease in the inductive reactance of the sample.

Figure 5d shows the modelling relationship between the ferrite phase fraction (65% to 85%) and inductive reactance of Q235 and Q355 at a frequency of 1500 Hz. The electromagnetic induction intensity increases with the rise of ferrite phase fraction. A reduction in the proportion of pearlite (is with a high dislocation density) leads to a decrease of obstruction effect of magnetic flux lines. This enhances the inductance and reduces the inductive reactance. For the same ferrite phase fraction, the inductive reactance of Q355 is greater than that of Q235. This is attributed to the smaller grain size of Q355, which results in a higher number of grain boundaries with elevated dislocation density. The high dislocation density reduces the maximum saturation magnetic density, explaining the increase in inductive reactance with the rise in the number of grain boundaries23.

When the ferrite phase fraction is within the range of 70% to 80%, the inductive reactance exhibits low fluctuation. However, when the ferrite phase fraction falls below 70%, the fluctuation in inductive reactance increases and follows a trend similar to the inductive reactance of air (with an inductive reactance of 0.2786 Ω). This is because the ferrite is α-Fe. When Fe atoms in the α-Fe lattice are excited by a magnetic field, the magnetic moments of the magnetic domains easily rotate, increasing the total magnetic moment in the direction of the external magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 6a. This change leads to an increase in the magnetic domains in the direction of the magnetic flux lines, thereby increasing the magnetic flux density in the ferrite regions. As a result, the magnetic induction intensity increases and the inductive reactance decreases. After carbon atoms enter the iron lattice as interstitial solutes, they cause local lattice distortions, increasing the lattice distortion energy, thereby leading to the formation and proliferation of dislocations. This mechanism has a significant impact on the strength, hardness and toughness of the material.

Pearlite is a mechanical mixture of Fe3C and α-Fe. The interface between Fe3C and α-Fe in pearlite contains a significant number of dislocations24. The total number of dislocations increases with the pearlite content. The increase in dislocations hinders the reorientation of magnetic domains in atomic clusters, leading to a decrease in the magnetization intensity within the pearlite regions23, as illustrated in Fig. 6b. However, this is not able to be used to explain the abrupt change in the inductive reactance signal when the ferrite phase fraction changes from 65 to 70%. This is because, at lower ferrite contents, a large amount of pearlite with high dislocation density obstructs the passage of magnetic flux lines. At this stage, the change in the inductive reactance signal is dominated by pearlite. As the ferrite content increases, the variation in the inductive reactance signal becomes primarily governed by the ferrite phase fraction. With the increase in ferrite phase fraction, the number of dislocations decreases and a sharp decline is presented in the inductive reactance signal. This observation is consistent with the findings of Sablik25 and Lo26.

Relationships between magnetic induction intensity and strength

In order to establish the relationship between electromagnetic signals and strength, tensile tests were conducted on samples with ferrite phase fractions ranging from 65 to 85%. Q235 and Q355 samples with different ferrite phase fractions were selected and cut into I-shaped samples with a total length of 45 mm, a width of 10 mm and a thickness of 2.5 mm for strength tests. The strain rate of the test is 2 mm per minute. The samples were polished with sandpaper to remove the surface oxide layer. The tensile tests were performed using a universal testing machine with flat grips to clamp the ends of the specimens. The experimental procedure is shown in Fig. 7a.

(a) Universal tensile testing machine experimental procedure (b) SEM test diagram of Q235 fracture (c) SEM test diagram of Q355 fracture (d) relationship between strength of Q235 sample and ferritic phase fraction (e) relationship between strength of Q235 sample and inductive reactance (f) relationship between strength of Q355 sample and ferritic phase fraction (g) relationship between strength of Q355 sample and inductive reactance.

Figure 7b,c show the tensile fracture surfaces of Q235/Q355 with ferrite content ranging from 65 to 85%. Numerous dimples were observed on the fracture surfaces, indicating the presentation of ductile fracture within tested samples. Q235/Q355 samples primarily consists of ferrite and pearlite. Ferrite is the ductile phase and these dimples are mainly attributed to the fracture of ferrite. In addition to the dimples, lamellar pearlite fracture with slip characteristics was also observed in Fig. 7b,c. Since pearlite is a mechanical mixture of ferrite and Fe3C, the fracture of pearlite mainly occurs by slip between ferrite and Fe3C, rather than by transgranular or intergranular fracture27. Consequently, the amount of lamellar Fe3C reflects the different pearlite contents. Figure 7(b-1) to 7(b-4) show that as the ferrite phase fraction decreases from 85 to 65%, the amount of lamellar Fe3C increases. Other areas mainly exhibit dimples caused by the fracture of ferrite. Figure 7b(b-5) shows the morphology of pearlite slip in Fig. 7b(b-4), where lamellar Fe3C can be observed. The lamellar black substance in the green dashed area is Fe3C, confirming that the slip region is pearlite. From Fig. 7(b-1) to 7(b-4), the increase in the amount of lamellar Fe3C can be observed, indicating an increase in pearlite content. High pearlite content inhibits ferrite deformation, leading to an increase in tensile strength, which is consistent with the electromagnetic testing results.

It can be seen in Fig. 7d,f that as the ferrite phase fraction increases in Q235/Q355, the tensile strength and yield strength of the samples decrease. Conversely, as the pearlite content increases, the strength of the steel increases. There are numerous dislocations at the Fe3C and α-Fe interfaces within pearlite. The total number of dislocations increases with the pearlite content. According to the Taylor’s equation, the yield strength of the material is proportional to the square root of the dislocation density. The increased dislocation density enhances the atomic-level obstacles within the lattice, making further atomic layer slip more difficult, thus increasing the yield strength of the material. The trends in tensile strength and yield strength are consistent with changes in the ferrite phase fraction. Therefore, the results demonstrate that the strength of the tested samples can be characterized based on the ferrite phase fraction. The relationship between the electromagnetic signal and strength is shown in Fig. 7e,g.

Relationships between magnetic induction intensity and hardness

To establish the relationship between electromagnetic signals and hardness, microhardness tests were conducted on samples with ferrite phase fractions ranging from 65 to 85%. Micro Vickers hardness tests were carried out on 10 × 10 × 10 mm3 samples with varying ferrite phase fractions. The load for the hardness measurement is 0.1 kg and the dwell time for the hardness measurement is 15 s. The experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 8a.

(a) Hardness experimental procedure (b) microhardness map (c) the hardness at different locations of the specimen (d) relationship between hardness of Q235 sample and ferritic phase fraction (e) relationship between hardness of Q355 sample and ferritic phase fraction (f) relationship between hardness of Q235 and Q355 sample and inductive reactance.

Five hardness points were tested on each sample, including both ferrite and pearlite microhardness, as shown in Fig. 8b. The hardness of each point was recorded in Fig. 8c. The results indicate that within the same sample, the microhardness of the first group of pearlite is higher than that of the fifth group of ferrite. The hardness was taken the average value of five groups, with the result showing Q355 is with higher hardness than Q235. Figure 8d,e show that as the ferrite phase fraction increases from 65 to 85%, the hardness of Q235 decreases from 185.9 HV to 124.2 HV and the hardness of Q355 decreases from 230.5 HV to 144.8 HV.

This is attributed to the smaller grain size of Q355, which results in a higher number of grain boundaries with elevated dislocation density. Pearlite is a phase in steel with a high dislocation density. The increased dislocation density implies that higher energy is required for atomic movement during hardness testing, which explains the increase in hardness. As the phase fraction of pearlite increases, the amount of cementite also rises. In pearlite, the presence of cementite in the structure contributes to the relatively higher hardness of pearlite. The interface between the ferrite and cementite phases exhibits a high dislocation density, which also contributes to the higher hardness. Mainly with the combined effects of two factors, there is a trend of increasing hardness as the pearlite phase fraction increases. Therefore, the hardness of the tested steel plates can be deduced from the measured ferrite phase fractions. The relationship between the inductance signal and the hardness can be determined, as shown in Fig. 8f.

Relationships between magnetic induction intensity and toughness

To establish the relationship between electromagnetic signals and toughness, impact tests were conducted on samples with ferrite phase fractions ranging from 65 to 85%. Q235 and Q355 samples with different ferrite phase fractions were selected and cut into samples with a total length of 55 mm, a width of 10 mm and a thickness of 5 mm. The samples were subjected to impact testing using an impact testing machine. The experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 9a.

Figure 9b,c show the impact fracture surfaces of Q235/Q355 with ferrite contents ranging from 65 to 85%. As the pearlite gradually decreases, the number of lamellar Fe3C gradually decreases. It can be concluded that cracks appearing when the pearlite proportion is high are primarily characterized by river-like cleavage and dimples. The cleavage fracture area contains a large amount of lamellar Fe3C, indicating that the crack initiation area is mainly caused by the slip of Fe3C. When fracture occurs in areas with a higher pearlite content, the crack source begins to slip from the lamellar pearlite, hence a high ferrite content inhibits excessive pearlite slip and increases impact energy. As the ferrite proportion increases, the number of dimples rises.

It can be seen from Fig. 9d that as the ferrite phase fraction in Q235/Q355 increases from 65 to 85%, the impact energy of the samples increases. Although high dislocation density can enhance the strength and hardness of the material, excessively high dislocation density may lead to the material becoming too brittle. This is because dislocation pile-up in the lattice restricts the ability for plastic deformation. In such cases, the material may fracture more easily under impact loads, displaying lower toughness. Therefore, the impact energy of the tested samples can be derived from the measured ferrite phase fraction. The relationship between the inductive signal and the impact energy is shown in Fig. 9e.

Discussions

The mechanism by which dislocations affect mechanical properties

The increases in coercivity and hysteresis loss are proportional to the root-square of dislocation density25. Lo26 investigated the influence of dislocations on domain walls by using the magneto-mechanical hysteresis modeling and revealed that the dislocation pinning effect is proportional to powers of dislocation density, which is the underlying mechanism for increasing coercivity. As the ferrite phase fraction increases, dislocation density decreases, hysteresis loss decreases, and reactance decreases. The relationship between reactance and ferrite phase fraction follows an exponential trend, which is consistent with the pattern observed in Fig. 5.

Mechanical properties of ferrite-pearlite low alloy steel are strictly determined by the properties of ferrite and pearlite phases28. The ferrite phase and pearlite phase provide ductility and strength/hardness for ferrite-pearlite steel, respectively29,30. Jiang28 investigated the changes in strength and hardness of ferritic-pearlitic steel after holding at 600 °C for 30 h, 80 h, 160 h and 300 h. The fraction of the pearlite phase decreases with the increase in holding time. The results are shown in the Fig. 10. The trends in strength and hardness are consistent with those in Figs. 7 and 8. The difference in magnitude is due to the varying alloy element content in the steel used by Jiang Y compared to Q235/Q355. It is noteworthy that different alloy element contents will directly result in variations in the strength and hardness of the samples Fig. 11a.

Variation trend in strength and elongation with treating time (a) yield strength (b) tensile strength (c) correlation between treating time and hardness28.

(a) The relationship between yield strength and ferrite phase fraction (b) the relationship between impact energy and experimental temperature (c) the mechanism by which dislocations affect strength (d) the mechanism by which dislocations affect hardness (e) the mechanism by which dislocations affect toughness.

Due to the lower dislocation density between dislocation walls, the ferrite layer exhibits greater plastic deformation capability compared to the cementite layer. Pearlitic structures hinder the movement of dislocations. As dislocations slide along the direction of shear stress, the number of dislocations accumulated at the interfaces increases layer by layer24. Consequently, the strength/hardness gradually increases while toughness gradually decreases. When the load-bearing capacity of the pearlitic structure reaches a critical value, they fractured because of the supercharged stress concentration in the dislocation tangle zones. The results are consistent with the pattern observed in Fig. 9.

The performance of pearlite plus ferrite microstructure depends on the relative amounts of ferrite and pearlite, ferrite grain size, pearlite lamellar spacing and ferrite chemical composition. Empirical formulas relating these factors to strength are as follows

In the formula, \({f}_{\alpha }\) represents the volume fraction of ferrite phase, \(d\) denotes the average diameter of ferrite grains, \(s\) stands for the average interlamellar spacing of pearlite and Mn, N, Si indicate the mass percentages of manganese, nitrogen and silicon respectively. According to the formula, Fig. 11a can be derived. As the volume fraction of ferrite phase decreases and the pearlite phase fraction increases, the material strength increases. Mn, Si and N enhance the strength of the material, which also explains why Q355 exhibits higher strength than Q235 under the same ferrite phase fraction. The exponent 1/3 in the formula indicates that the yield strength and tensile strength vary nonlinearly with changes in the volumes of ferrite and pearlite phases. This is consistent with the patterns observed in Fig. 7.

Plasticity decreases with increasing pearlite content and increases with refinement of ferrite grains. Increasing the volume percentage of pearlite significantly reduces the maximum uniform strain and total strain at fracture. In steel composed of ferrite and pearlite, the brittle-to-ductile transition temperature Td in relation to various microstructural factors and compositions can be expressed by the following formula:

In the formula, \(P\) represents the size of pearlite colonies, \(t\) denotes the thickness of cementite lamellae within pearlite and \({N}_{f}\) indicates the weight percentage of nitrogen in its solid solution state. According to the formula, Fig. 11b can be derived. It is observed that the brittle-to-ductile transition temperature increases with increasing pearlite content. With an increase in carbon content in steel (corresponding to an increase in pearlite content), the brittle-to-ductile transition temperature rises, leading to a significant decrease in impact toughness in the ductile state. Refining ferrite grain size and pearlite colony size, reducing silicon and carbon content are beneficial for toughness, whereas solid solution strengthening is detrimental to toughness. This also explains why Q355 exhibits higher toughness than Q235 under the same ferrite phase fraction. This is consistent with the patterns observed in Fig. 9.

There are numerous dislocations present in pearlite. When the sample is subjected to external stress, atoms in the ferrite lattice undergo slip, generating a small amount of dislocation. The high density of dislocations in pearlite inhibits the slip of ferrite crystal planes. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 11c, clusters of iron atoms in ferrite exhibit greater movement, whereas Fe3C in pearlite restrains the deformation of α-Fe, resulting in smaller movement distances for clusters of iron atoms. Consequently, an increase in pearlite phase fraction enhances the material’s resistance to deformation, leading to increased strength. Similarly, during hardness testing when stress is applied to ferrite, the slip of iron atom clusters in ferrite is also restrained by pearlite. Thus, as depicted in Fig. 11d, the role of pearlite also manifests in suppressing plastic deformation of α-Fe and enhancing hardness. However, the high dislocation density limits the plastic deformation capability of ferrite. Therefore, with an increase in pearlite proportion, the material is more prone to fracture under impact loads, exhibiting lower toughness, as shown in Fig. 11e.

The essence of electromagnetic signals lies in the reorientation of magnetic domains, which is influenced by dislocation density. Therefore, when measuring steels containing both ferrite and pearlite phases, the signal strength is primarily affected by pearlite, which typically exhibits high dislocation density. As the proportion of pearlite increases, the increase in dislocation density hinders the reorientation of magnetic domains. This manifests in electromagnetic signals as an increase in dislocation density with increasing pearlite content, showing a corresponding pattern in electromagnetic signal variation.

The changes in mechanical properties correlate with variations in dislocation density. This demonstrates that the variation pattern of electromagnetic signals can reflect changes in mechanical properties. This characterization can be refined by incorporating Eqs. (2) and (3).

On-site measured signals

On production site, the U-shaped sensor is positioned 38 mm away from the surface of the plate to ensure signal stability while preventing damage to the sensor during the steel plate movement.

Figure 12a shows the range of inductive signals for Q235 samples with ferrite phase fractions between 65 and 85% in production and laboratory measurements. As the ferrite phase fraction increases, the inductive signal of Q235 decreases. The pattern of signal variation is consistent with the laboratory test results. The error between experimental signals and field signals is less than 0.0002. Figure 12b–d illustrate the ranges of strength, hardness and impact energy for Q235 samples with ferrite phase fractions between 65 and 85% in both production and laboratory measurements. The strength error is less than 18 MPa. The hardness error is less than 11 HV and the impact energy error is less than 6 J. Experimental results indicate that the multi-frequency electromagnetic characterization system can be used for real-time online detection of ferrite phase fractions in industrial applications.

To address the discrepancies between laboratory tests and field measurements of the U-type sensor, a software system was designed and correction factors K and C were applied to adjust the testing patterns. Additionally, vibrations occurring during the production process in the field can affect test results. These vibrations essentially alter the lifting distance, which should be considered when further optimizing the laboratory fitting curves.

Conclusions

This paper investigates relationships between electromagnetic response and the ferrite phase fraction. Relationships of ferrite phase fraction with strength, hardness and toughness of steels are also examined. A non-destructive characterization system of real-time online characterization for steel microstructures and properties is developed. The system has been applied in actual steel production processes and can measure the ferrite phase fraction, strength, hardness and toughness of steel plates. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

1.

A multi-frequency electromagnetic technology instrument was prepared under laboratory conditions and measurements were conducted on Q235 and Q355 steels. The relationship curves between reactance and microstructure/mechanical properties were established. The results indicate that as the volume fraction of ferrite increases from 65 to 85%, the inductive reactance decreases from 0.2240 to 0.2195. The relationship curves between inductive reactance and the strength, hardness and toughness of steels were also established, showing that as the inductive signal increases, both strength and hardness increase, while toughness decreases.

-

2.

Based on the laboratory-measured database, a multi-frequency electromagnetic technology system and sensors were developed and applied in actual production. A protective shell was designed for the sensors, making them more suitable for on-site production testing. Field test results show that the error between experimental and field signals is less than 0.0002. The strength error is less than 10 MPa, the hardness error is less than 6 HV and the impact energy error is less than 5 J.

-

3.

The pearlite phase is where the dislocation concentration. Therefore, as the volume fraction of pearlite increases, the dislocation density also increases. The increase in dislocation density enhances the inductive reactance signal, strength and hardness, while reducing toughness.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality agreement required by Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgical Co., Ltd. but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shahabuddin, M., Brooks, G. & Rhamdhani, M. A. Decarbonisation and hydrogen integration of steel industries: Recent development, challenges and technoeconomic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 395, 136391 (2023).

Gao, W. et al. Comprehensive utilization of steel slag: A review. Powder Technol. 422, 118449 (2023).

Watari, T. et al. Limited quantity and quality of steel supply in a zero-emission future. Nat. Sustain. 6(3), 336–343 (2023).

Csernak, S. F. & McCormac, J. C. Structural steel design. Pearson Education, Incorporated (2023).

Ogundele, G. & White, W. Some observations on corrosion of carbon steel in aqueous environments containing carbon dioxide. Corrosion 42, 71–78 (1986).

Dwivedi, D., Lepková, K. & Becker, T. Carbon steel corrosion: A review of key surface properties and characterization methods. RSC Adv. 7, 4580–4610 (2017).

Katayama, H. et al. Corrosion simulation of carbon steels in atmospheric environment. Corros. Sci. 47, 2599–2606 (2005).

Jiang, W. C. et al. Determination of the through-thickness residual stress in thick duplex stainless steel welded plate by wavelength-dependent neutron diffraction method. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 196, 104603 (2022).

Li, Y. W. et al. Fabrication of high borated austenitic stainless steel thick plates with enhanced ductility and toughness using a hot-roll-bonding method. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 799, 140212 (2021).

Krichel, T., Olschok, S. & Reisgen, U. Comparison of penetration depth in bead-on-plate welds of thick-walled steel sheets with laser beam welding in vacuum and electron beam welding. Vacuum 203, 111314 (2022).

Köhnen, P. et al. Understanding the process-microstructure correlations for tailoring the mechanical properties of L-PBF produced austenitic advanced high strength steel. Addit. Manuf. 30, 100914 (2019).

Shen, J. et al. Real-time in-line steel microstructure control through magnetic properties using an EM sensor. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 490, 165504 (2019).

Afkhami, S. et al. Thermomechanical simulation of the heat-affected zones in welded ultra-high strength steels: Microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 213, 110336 (2022).

Shen, J. et al. Characterization on multiphase microstructures of carbon steels using multi-frequency electromagnetic measurements. Measurement 226, 114140 (2024).

Davis, C. L., Strangwood, M. & Peyton, A. J. Overview of non-destructive evaluation of steel microstructures using multifrequency electromagnetic sensors. Ironmak. Steelmak. 38(7), 510–517 (2011).

Xiao, S. et al. Non-destructive characterization on multiphase structures of duplex stainless steel using multi-frequency electromagnetic sensor. NDT & E Int. 138, 102892 (2023).

Yanagawa, S. & Watanabe, I. Multiscale finite element analysis of yield-point phenomenon in ferrite-pearlite duplex steels. ISIJ Int. 64(5), 874–880 (2024).

Jolfaei, M. A., Shen, J. & Smith, A., et al. EM Sensor System for Characterisation of Advanced High Strength Strip Steels (2019).

Handoko, W., Pahlevani, F. & Sahajwalla, V. Enhancing corrosion resistance and hardness properties of carbon steel through modification of microstructure. Materials 11(12), 2404 (2018).

Trivedi, R. et al. Study of strength and toughness in pearlitic wheel steel via microstructural alteration. Mater. Today Commun. 39, 109255 (2024).

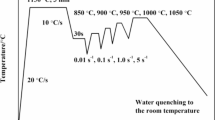

Ayush, A., Dewangan, S. & Ishwar, S., et al. Effect of water quenching into strength, hardness and microstructure of the welded AA 6061 plates. World J. Eng. (2024).

Kulkarni, A. R., Raju, P. V. & Sarma, P. P., et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 0.18%-C steel samples processed through five different heat treatment techniques. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. D 1–16 (2024).

He, Q. F. et al. A highly distorted ultraelastic chemically complex Elinvar alloy. Nature 602(7896), 251–257 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. In situ study of cementite deformation and its fracture mechanism in pearlitic steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 731, 93–101 (2018).

Sablik, M. J., Yonamine, T. & Landgraf, F. J. G. Modeling plastic deformation effects in steel on hysteresis loops with the same maximum flux density. IEEE Trans. Magn. 40(5), 3219–3226 (2004).

Lo, C. C. H., Kinser, E. & Jiles, D. C. Modeling the interrelating effects of plastic deformation and stress on magnetic properties of materials. J. Appl. Phys. 93(10), 6626–6628 (2003).

Hua, J. et al. Microstructure evolution and properties of wheel steel under different pearlite content and slip ratio conditions. Wear 512, 204526 (2023).

Jiang, Y. et al. Evolution of mechanical properties of ferrite and pearlite phases during spheroidization process and their relationship to the overall properties of low alloy steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 29, 5437–5446 (2024).

Al-Abbasi, F. M. Micromechanical modeling of ferrite-pearlite steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 527(26), 6904–6916 (2010).

Ha, T. K., Lee, C. H. & Kim, K. S. Spheroidization behavior of cementite in a high carbon steel. Mater. Sci. Forum. 654, 150–153 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52204340) and the Guangxi Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2022GXNSFBA035621). The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Advanced Manufacturing and Materials Centre of Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG), University of Warwick, for providing facilities and equipment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chen Zhang and Jialong Shen wrote the main manuscript text, while Zhengbing Meng prepared Figs. 1–3. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Shen, J., Meng, Z. et al. Research and application of multi-frequency electromagnetic technology in real-time online characterization of steel microstructures and mechanical properties. Sci Rep 15, 400 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84502-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84502-0