Abstract

Endophytes are microorganisms residing in plant tissues without causing harm and their relevance in medicinal plants has grown due to their biomolecules used in pharmaceuticals. This study isolated two endophytic bacterial strains from the leaves of M. oleifera and P. betel collected from Junagadh Agricultural University. The isolates were characterized morphologically and physio-biochemically, confirming them as gram-positive or gram-negative rods and cocci. Identification using 16S rRNA gene sequencing identified isolates belonging to various genera, including Priestia aryabhattai and Kocuria rhizophila The SEM characterization of the five selected isolates revealed diverse morphological structures, including coccus and rod shapes, organized in various formations. Isolates varied in size, with N3 (Kocuria rhizophila) cocci and S5 (Priestia aryabhattai) rods. Metabolomic analysis using GC/MS and LC–MS revealed diverse metabolic profiles with key compounds like n-Hexadecanoic acid, Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, Dihydrocapsaicin, and β-Homoproline, highlighting the potential of these endophytic bacteria in agricultural applications due to their roles in membrane integrity, antioxidant properties, stress response, and antibacterial activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endophytes, known as the largest unexplored reservoirs forming a “ware house of natural bioactive compounds on the earth”1. Endophytes are micro-organisms (bacteria and fungi) colonizing themselves in living, interior tissues of host plants without causing any overt negative effects to the host2. Endophytes are ubiquitous, found in every plant and shows vast biodiversity3. Endophytes show a great biodiversity of adaptations, developed in special and sequestered environments4. This endophytic diversity may be similar with the diversity of their host plant. The most common endophytes are fungi and bacteria, but comparatively fungi are the more commonly isolated and studied endophytes3.

Medicinal plants are gaining global attention owing to the fact that the herbal drugs are cost-effective, easily available and with negligible side effects. These plants harbour an untapped source of bioactive metabolites and large number of microorganisms, more specifically bacteria and fungi, called endophytes. Endophytes are the microorganisms that reside within the plant tissue without showing any overt negative effect. Nearly all plant species that exist in the earth harbour one or more endophytic microorganisms5. To survive in the plant tissue, these endophytes decompose plant metabolites and obtain nutrition and energy. Due to long-term co-evolution of endophytes with their host plant, these endophytes have adapted to the special microenvironments by uptake of plant genome through genetic variation6.

Endophytes are also an important source of pharmaceutical bioactive metabolites such as antitumor, antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive drugs, and many related compounds. Endophytes, also known for the production of different natural products and exhibit a wide range of biological activity and classified into numerous categories, which include steroids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, lactones alkaloids quinines, lignans7. Wide range of reports on numerous new endophytic species are evident which may exist in medicinal plants8.

Moringa oleifera, the most widely found species of the Moringaceae family thrives in tropical insular climate. The tree ranges from 5–10 m in height9. Phytochemical analyses have revealed that Moringa leaves are a rich source of potassium, calcium, phosphorous, iron, vitamins A and D and essential amino acids10. The leaf extracts of Moringa contain antioxidant properties and inhibit the peroxidation of linoleic acid. Extracts of leaves were also shown to prevent the bleaching of carotene and scavenge radicals in the DPPH radical scavenging assay11.

Piper betel is the most important and useful asexually propagated cash crop having various cultivars12. It belongs to Piperaceae family and is a shed loving plant. It has a perennial creeper and bears leaves that are 4–7 inch long and 2–4 inch broad. It bears both male and female flowers. It is originated from Malaysia but is distributed extensively in South and Southwest China13.

Result

Isolation of endophytic bacteria from medicinal plants samples

Nutrient agar media has been used for the isolation of endophytic bacteria and different colonies have been recovered after pure culture plate. Moringa oleifera isolate code S5 was identified, and from Piper betel isolate code N3 was obtained.

Cultural characterization

In vitro multiplications of bacterial isolates were carried out on nutrient agar plates and.

colonial characteristics were recorded in size, shape, elevation, margin, texture, opacity and pigment. Isolate S5, from Moringa oleifera, exhibits medium-sized, circular colonies that are opaque with a white pigment, entire margin, convex elevation, and a buttery texture. In contrast, isolate N3, from Piper betel, forms small, circular colonies that are opaque with a yellow pigment, undulate margin, crateriform elevation, and a dry texture. These findings are similar to the findings of14.

Microscopic characterization

Microscopic characterization of the isolates was carried out by gram’s staining for cellular morphological characterization. Different isolates displayed different cell sizes and morphologies when viewed under the microscope. Isolate S5 is a Gram-negative short rod that does not form spores, while isolate N3 is a Gram-positive coccus that forms spores.

Molecular identification by 16s rRNA gene amplification

The endophytic bacterial isolates under study were identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. A fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using 16S universal primers listed in Table S6. The sequencing was carried out on capillary sequencer (Applied Bio Systems 3130). Partial 16S rRNA gene sequence of studied bacteria were analysed with nucleotide BLAST search in GenBank of NCBI.

Scanning electron microscopic characterization of isolates

The scanning electron microscopic characterization of the two isolates also showed that that isolate S5, a short rod-shaped bacterium, measures 1.612–6.783 μm in length and 0.707–0.833 μm in width, and exhibits motility. Isolate N3, a cocci-shaped bacterium, measures 0.848–1.559 μm in length and 0.638–0.646 μm in width, and is also motile (Fig. 1).

Untargeted metabolomics profiling by GC/MS

Untargeted metabolomics is a valuable method for simultaneously analysing a large number of molecules without prior information. GC–MS chromatogram displaying different peaks of the compounds shown in S1–S4 in in supplementary file. The chromatogram displays peak intensity plotted against retention time (min). This investigation found six chemicals in M. Oleifera leaf extract and fourteen compounds in the S5 isolate.

This study revealed six compounds were present in P. betel leaves extract and fourteen compounds were present in N3 isolate (Tables 1 and 2).

Untargeted metabolomics profiling by LC–MS

Untargeted metabolomics is a valuable method for simultaneously analysing a large number of molecules without prior information. LC–MS chromatogram displaying different peaks of the compounds shown in S5-S8 in supplementary file. The chromatogram illustrates the relationship between peak intensity and retention time (min). This investigation found 41 chemicals in M. Oleifera leaf extract and fourteen compounds in the S5 isolate.

This investigation found 43 chemicals in P. betel leaf extract and fourteen compounds in the N3 isolate.The heat map displays the expression levels of various compounds, with a focus on comparing samples labelled N3 B and N3 L. The color gradient ranges from blue (low expression) to red (high expression), indicating the relative abundance of each compound. In the N3 B sample, several compounds are notably upregulated, as indicated by the intense red coloration (Tables 3 and 4).

Discussion

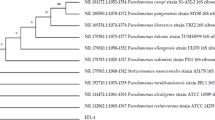

The 16S rRNA gene sequence can be used to identify the genus and species of isolates. The biochemically most potent isolates are listed in Table 5 along with their accession ID and percentage of identity with the query sequence. S9 to S12 in supplementary file present the gene sequence and gel image obtained from the sequencing of the isolates’ 16S rRNA gene. Figures 2 and 3 represent phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequencing of isolate S5 and N3 compared with the most closely related organisms.

The heat map (Figs. 4 and 5) provided illustrates the relative abundance of six distinct chemical compounds: Dodecyl acrylate, n-Hexadecanoic acid, Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl)-, 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, bis(2-methylpropyl) ester, Oleic acid, and Methyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate. The intensity of the colours on the heat map serves as an indicator of the abundance levels, with red denoting the highest abundance and blue representing the lowest abundance. Notably, the compound n-Hexadecanoic acid demonstrates the highest relative abundance, evidenced by its prominent red coloration on the map. As a saturated fatty acid, it is a key component of membrane lipids, contributing to the structural integrity and fluidity of cell membranes. This is essential for maintaining proper cell function and facilitating the transport of molecules across the membrane15.

Palmitic acid is also involved in energy storage, serving as a major component of triacylglycerols, which are stored in lipid droplets within the cell. In contrast, Methyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate is characterized by the lowest relative abundance, marked by its blue shading. This visual representation allows for a clear comparative analysis of the abundance levels of these compounds, providing valuable insights into their relative concentrations within the sample.Dodecyl acrylate and Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl)- are the anozther abundant compound in N3 isolate as compared to plant leaf sample. Dodecyl acrylate, a fatty acid ester, can be involved in the formation of plant cuticles, providing a protective barrier against water loss, pathogens, and environmental stress. It may also play a role in signalling pathways related to stress responses16. On the other hand, Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl), is an antioxidant compound that helps protect plant cells from oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS). This compound aids in maintaining cellular health and preventing oxidative stress, which can impair cell function and lead to cellular damage17.

The higher abundance of these compounds in the N3 (Fig. 5) isolate sample suggests an enhanced protective and stress-responsive capacity. Moreover, Methyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate, which is slightly upregulated in N3 isolates broth, plays a pivotal role in N3 isolates by mitigating autoxidation and enhancing the frictional stability of materials subjected to stress18. By studying the upregulated and downregulated compounds in S5 broth compared to compounds identified from Moringa leaves.

The upregulated compounds in S5 isolate (Fig. 4) are Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl);1,2-Benzendicarboxylic acid, buty2-ethylhexyester; Propanedioic acid, phenyl, n-Hexadecanoic acid and Dodecyl acetate. Our research identified a significant upregulation of Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl) (hereafter referred to as Pyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl)) in the broth of isolate N3.

This compound possesses well-established antioxidant properties, as demonstrated by its ability to scavenge free radicals in a reducing power assay. Free radicals are highly reactive molecules that can damage cells and contribute to the development of various chronic diseases.

Therefore, the upregulation of Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl) in isolate N3 suggests a potential protective mechanism against oxidative stress16. Other than Pyrrolo [1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl)-, n-Hexadecanoic acid is upregulated in broth of isolate which function as major component of plant cell membranes. N-hexadecanoic acid contributes significantly to membrane fluidity and stability, two crucial properties for various cellular processes in plants.

These processes include the transport of essential ions required for growth, signal transduction pathways that allow plants to respond to their environment, and maintaining the integrity of the cell itself15. Potentially influencing these cellular processes, the S5 isolate may contribute positively to plant health and function. The S5 isolate’s broth reveals not only n-hexadecanoic acid, but also upregulated levels of propanedioic acid (malonic acid) and dodecyl acrylate, suggesting a multi-faceted contribution to plant health (Fig. 6).

Malonic acid plays significant roles in plant development and stress responses. It acts as a precursor in the synthesis of various important compounds within plants, and it also contributes to plant defence mechanisms against biotic (e.g., fungal or insect attack) and abiotic (e.g., drought or temperature extremes) stresses19. Dodecyl acrylate, on the other hand, exhibits antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant human pathogens16.

The most abundant compound identified through LC–MS (Fig. 7) in N3 broth is Dihydrocapsaicin, which significantly contributes to plant defence. Dihydrocapsaicin plays a crucial role in inhibiting the growth of fungal pathogens that affect plants, thereby enhancing the plant’s defence mechanisms against fungal diseases. This inhibition not only helps in protecting the plants from pathogenic invasions but also promotes overall plant health and resilience. The presence of Dihydrocapsaicin in N3 broth underscores its importance in bolstering the plant’s natural defence system20.Another abundant compound identified in N3 broth is(+ /-)-16(17)-Epoxy-4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,19Z-docosapentaenoic acid(DPA).Like eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), DPA serves as a substrate for the synthesis of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) such as resolving and protections, which possess significant biological activity.

These SPMs play a critical role in resolving inflammation and promoting tissue repair, highlighting DPA’s potential in modulating inflammatory responses and supporting overall health21. Several bioactive compounds identified in N3 broth demonstrate diverse and significant roles in plant health and defence, (3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl) ethanol acts as a potent biological antioxidant in cell culture experimental models, providing essential protection against oxidative stress22. γ-Hexalactone exhibits strong antimicrobial activity against Phytophthora infestans, a notorious plant pathogen, thereby enhancing plant disease resistance23. 7 β-Hydroxy Wortmannin plays a crucial role in vesicular trafficking and organelle dynamics within plant cells, essential processes for maintaining cellular function and integrity21.

Additionally, Pinolenic acid ethyl ester interacts with phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA) and jasmonic acid (JA), which are pivotal for plant growth, development, and stress responses24. These compounds collectively contribute to the robust defence mechanisms and physiological regulation in plants, highlighting their potential applications in agriculture.One of the most abundant compounds (Fig. 4) in S5 broth as compared to moringa’s leaf sample is D-erythro-Sphinganine, prominently marked by a red bar, signifying a high concentration. D-erythro-Sphinganine, a significant sphingolipid metabolite, plays a crucial role in various cellular processes in plants. Notably, sphingolipid-mediated signalling pathways, in which D-erythro-Sphinganine is a key component, are fundamental in regulating programmed cell death (PCD).

This process is essential for plant development and defence mechanisms, ensuring the removal of damaged or infected cells and maintaining cellular homeostasis17. Other abundant compounds found in the S5 broth include β-Homoproline, which plays a pivotal role in plant physiology. β-Homoproline is implicated in cell wall signal transduction cascades, which are crucial for maintaining the structural integrity and functionality of the plant cell wall.

These signal transduction pathways are essential for the plant’s ability to perceive and respond to various environmental stimuli, thereby contributing to stress tolerance mechanisms25. Another abundant compound identified in S5 broth is 1,2-Di-(9Z,12Z,15Z-octadecatrienoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, which plays a crucial role in seed biology. This compound is involved in providing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) for the synthesis of triacylglycerols (TAGs) in seeds. PUFAs are essential components of plant oils and are vital for seed germination, storage, andenergy metabolism26.

Among the abundant compounds identified in S5 broth (Fig. 6), Ala-Trp-Arg stands out for its multifaceted role in plant physiology and signalling pathways. This tripeptide not only participates in protein synthesis but also exerts profound effects on plant growth, defence mechanisms, and responses to environmental stressors27. D-Pipecolinic acid stands out for its significant role in regulating plant systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and basal immunity against bacterial pathogens. SAR is a crucial defence mechanism in plants that confers broad-spectrum resistance following an initial exposure to a pathogen28.

Among the abundant compounds identified in S5 broth are Trp-Ala-Arg and Vigabatrin, which exemplify the diverse roles of bioactive peptides in plants. Trp-Ala-Arg is recognized for its potential in growth regulation and stress responses, underscoring its importance in enhancing plant resilience and adaptation to environmental challenges. Meanwhile, Vigabatrin demonstrates multifaceted bioactivities including antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory properties29.

Methods

The investigation was carried out at the “Department of Biotechnology, College of Agriculture, Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh” during 2023–2024.

Sample collection

The fresh and healthy leaves ofmedicinal plants: M. oleifera and P. betel were collected from Department of Biotechnology, Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh. Each sample was tagged and placed in separate polythene bags and processed within 24 h of collection. Fresh plant materials were used for isolation of endophytic bacteria to reduce the chance of contamination.

Sterilization procedure of sample

For the pre-treatment of leaf samples and isolation of endophytic bacteria all the leaf samples were excised and subjected to a surface sterilization procedure described by30. The procedure for sample pre-treatment is shown below; the efficiency of surface sterilization was checked by imprint method31. The samples were also washed with distilled water and inoculated into nutrient broth containing bavistin (30 µg/ml) media as a control to check growth in liquid medium.

Sample inoculum

Leaves were crushed in sterile distilled water using mortar and pestle and plant extracts were prepared. About 1 ml of crushed samples were serially diluted and 0.1 ml was spread onto nutrient agar (NA) medium. Plates were incubated at 35 °C for 2–3 days.

Characterization of isolates

Isolated endophytic bacteria were phenotypically characterized for growth characteristics on Nutrient agar, colony morphology and Grams reaction by using standard procedures following14.

Molecular identification by 16 s rRNA gene amplification

Primers for 16S rRNA genes were selected from standard scientific literature32. Table 6 shows sequences of the primers used to amplify and detect 16S rRNA genes. A fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using 16S universal primers. Each pair of primers were highly specific and gave a PCR product of known size that was easily identified by electrophoresis on agarose gel.

Lab procedure

Uncontaminated QC passed culture plates were used to obtain 1–2 well isolated colonies which were suspended in 50μL of Molecular Biology Grade Water mixed well. The suspension was incubated for 10 min at 95 °C and then centrifuged briefly. The supernatant of the lysate solution was used as template for PCR amplification using the universal primers 16S27F (5’-CCA GAG TTT GAT CMT GGC TCA G-3’) and 16S1492R (5’- TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3’)33. The amplified PCR product was further purified by salt-precipitation, then subjected to cycle sequencing using BDT v3.1 chemistry and subsequently sequenced on an ABI 3500XL Genetic Analyser. Additional internal primers were used to obtain near-full length sequence to generate good quality base reads covering the target.

Bioinformatics method

The .ab1 trace files obtained after sequencing were manually curated, converted into a fasta read file and then assembled into a contiguous sequence and exported as a FASTA file. The consensus sequence was subsequently subjected to database search against the SILVA database v13834. using the BLAST tool35. For the phylogenetic analysis, upto 10 closest-neighbour sequences belonging to different taxa from amongst the top 1000 hits with highest similarity in the search results were retrieved from the database and aligned using the MUSCLE aligner36. The multiple sequence alignment was manually inspected and used to produce a consensus phylogram using maximum likelihood or neighbour joining algorithm with 1000 iterations using MEGA11 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis, version 11) software.

Scanning electron microscopy

A loopful of the bacterial isolates colony was picked from their respective fresh culture plates and a light smear was made on the aluminium stub with the help of inoculating needle. The smeared stub was then flooded with 4% glutaraldehyde and kept in a fridge at 4 °C for 24 h. The following day the smeared samples were dehydrated by using gradient dilution of acetone in a concentration ranging from 30, 50, 70, 80, 90 and 100% and treating each sample by dipping into dilution of each respective concentrations in the order of 30% to 100% for 15 min. The samples treated by dipping in acetone concentration of 100% was repeated for second time for another 15 min for each sample. The dehydrated samples were then coated in a spotter coater having gold palladium mixture plate and observed under scanning electron microscope.

Metabolomics study

Untargeted metabolomic profiling by GC/MS

Untargeted metabolomics profiling by GC/MS was conducted on leaves and bacterial cultures of M. oleifera and P. betel, using powdered and broth samples stored at 4 °C. For the extraction of metabolites, 100–200 mg of leaf samples were crushed in liquid nitrogen, followed by the addition of 1.4 to 1.5 ml methanol. The extract was sonicated for 5–10 min and then heated in a water bath at 70 °C for 10 min. After adding 1 ml of M. Q. water and vortexing for 30 s, 1 ml of chloroform was added, vortexed, and centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The polar (methanol and water) and non-polar (chloroform) phases were separated and dried in a vacuum concentrator at 42–45 °C, then stored at − 20 °C. For derivatization, the next day, the samples were dried in a microwave at 40 °C for 8:30 min, cooled to room temperature, and mixed with 50 µl pyridine. Methoxylamine hydrochloride (20 mg/ml in pyridine) was added, vortexed, sonicated, and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min.

Then, 100 µl MSTFA was added, and the samples were incubated again at 37 °C for 60 min. Both phases were mixed, centrifuged, and 400–600 µl of the upper supernatant was taken for GC/MS analysis. Two µl of the sample was injected into the GC/MS, and the data obtained were analysed using MS libraries for identification, followed by statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 10.0.

The GC/MS analysis was performed using a Shimadzu GC-2010 plus (Plate: 3.1) equipped with a DB17MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm). The system’s oven temperature could reach up to 450 °C, with the injector port set at 280 °C and utilizing a split injection mode. The AFC pressure ranged from 0 to 970 kPa, while the column oven was maintained at 50 °C, and helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The MS interface had a direct connection with the capillary column, set at 250 °C. The ion source operated in EI mode, with options for PCI and NCI, maintaining an ion source temperature of 250 °C. The mass analyser, a metal quadrupole mass filter with a pre-rod, covered a mass range of m/z 1.5–1090, and the detector voltage was set at 1.3 kV. The software operated in Full Scan mode, with optional access to various mass spectrum libraries, including NIST, Wiley, Pesticide Library, FFNSC Library (Flavor and Fragrance), and Drug Library.

Untargeted metabolomic profilingby LC/MS

Untargeted metabolomic profiling by LC/MS involved extracting metabolites following the method described with minor modifications. The workflow started with 0.6 gm of powdered plant material placed in a 15 ml centrifuge tube, to which 10 ml of a chloroform:methanol (1:2) solvent was added. The mixture was left at room temperature for 2 days. After this period, the extract was centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 10 min and filtered using Whatman no. 1 filter paper. The solvent was evaporated using a water bath at 65 °C, and then 200 μl of methanol was added (for leaf samples, 200 μl extract was dissolved in 1 ml methanol). This extract was briefly vortexed for proper mixing and transferred to LC vials with 250 μl glass inserts for LC–MS analysis. The LC/MS parameters were set as required, and 10 μl of the sample was injected into the LC for observation. After the sample run, the data were analyzed using MS libraries for identification, followed by statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 10.0.

The LC/MS analysis was performed using a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C-18 column (3.0 × 100 mm, 1.8-micron) maintained at 25 °C, with an injection volume of 10 µl. The mobile phase was set in positive ionization mode with A being 0.1% formic acid in water and B being 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile, flowing at 0.3 ml/min. The gradient started with B at 5% at 0 min, increasing to 35% at 2 min, 95% at 8.50 min, remaining at 95% until 15 min, then returning to 5% at 16 min and held until 20 min, with a total run time of 20 min. The QTOF conditions were set to Auto Ms/Ms mode, with specific parameters including positive ESI ionization mode, a drying gas temperature of 300 °C, drying gas flow of 8 L/min, nebulizer pressure at 35 psig, vaporizer/sheath gas temperature of 350 °C, and sheath gas flow at 11 L/min. The Vcap was set to 3500 V, fragmentor to 140 V, skimmer to 65 V, and Oct 1 RF Vpp to 750 V. Collision energies were set at 10, 30, 40, and 60 V for m/z values of 100, 300, 500, and 700, respectively. The precursor per cycle maximum was 1, with an absolute threshold of 200 counts and a relative threshold of 0.01%. The mass range for MS was 100–1700, and for MS/MS it was 40–1000.

Statistical analysis

The above experiments were carried out in triplicate replications. The data obtained from their mean values were used for statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) for the interpretation of results.

Consent to participate/publish

As the corresponding author of this work, I hereby declare that all involved authors have provided their appropriate consent for the entire research to be conducted, and that all involved authors have approved of the effort to be published.

Conclusion

Endophytes are microorganisms that enter the inside tissues of host plants without causing any negative effects. Endophytes, which may be found in nearly every plant species, have a huge biodiversity and have evolved to unique microenvironments as a result of long-term coexistence with their host plants. Among these adaptations include increased resistance to diseases, herbivores, and other environmental challenges. Endophytes produce a wide range of natural products, including steroids, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, lactones, alkaloids, quinones, and lignans, and are a significant source of pharmaceutical bioactive metabolites such as antitumor, antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral compounds.

Medicinal plants, such as Moringa oleifera and Piper betel, are particularly valuable for studying endophytes due to their rich nutrient profiles and therapeutic properties. M. oleifera leaves are known for their high content of potassium, calcium, phosphorous, iron, vitamins A and D, and essential amino acids, as well as their antioxidant properties. P. betel, a perennial creeper, is widely used for its medicinal benefits and harbours a diverse range of endophytic microorganisms. The isolation and characterization of endophytic bacteria from these plants involve surface sterilization, sample inoculation, and various analyses, including molecular identification by 16S rRNA gene amplification and phenotypic characterization. These processes help identify specific endophytes, such as Priestia aryabhattai from M. oleifera and Kocuria rhizophila from P. betel, which have shown potential in promoting plant growth, nutrient solubilisation, and antagonistic activity against pathogens.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, with accession number N3: PQ192162, S5: PQ192159, respectively. With the agreement of all relevant co-authors, the principal author hereby declares that information and resources related to the work described will only be made available upon request to the corresponding author, Dr. S. B. Bhatt (sbbhatt@jau.in).

References

Nicolaou, K. C. et al. Total synthesis of taxol. Nature 367, 630–634 (1994).

Bacon, C. W. &White, J. F. Microbial Endophytes 3–29. Marcel Dekker.

Strobel, G. A. Endophytes as sources of bioactive products. Microb. Infect. 5, 535–544 (2003).

Owen, N. L. & Nicholas, H. Endophytes—The chemical synthesizers inside plants. Sci. Progress 87(2), 79–99 (2004).

Strobel, G., Daisy, B., Castillo, U. & Harper, J. Natural products from endophytic microorganisms. J. Nat. Prod. 67, 257–268 (2004).

Germaine, K. et al. Colonisation of poplar trees by gfp expressing bacterial endophytes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48, 109–118 (2004).

Germaine, K. et al. Colonisation of poplar trees by gfp expressing bacterial endophytes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48, 109–118 (2004).

Sturz, A. V., Christie, B. R., Matheson, B. G. & Nowak, J. Biodiversity of endophytic bacteria which colonize red clover nodules, roots, stems and foliage and their influence on host growth. Biol. Fertil. Soils 25(1), 13–19 (1997).

Zhang, Y. et al. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial epiphytic and endophytic fungi from marine organisms: Isolation, bioassay and taxonomy. Mar. Drugs 7, 97–112 (2009).

Anwar, F., Latif, S., Ashraf, M. & Gilani, A. H. Moringa oleifera: A food plant with multiple medicinal uses. Phytother. Res. 25, 17–25 (2007).

Gowrishankar, R. et al. Trace element studies on Tinospora cordifolia (Menispermaceae), Ocimum sanctum (Lamiaceae), Moringa oleifera (Moringaceae), and Phyllanthus niruri (Euphorbiaceae) using PIXE. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 133(3), 357–363 (2010).

Sindhuraju, P. & Becker, K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam.) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 2144–2155 (2003).

Patra, A. P., Mukherjee, A. K. & Acharya, L. Comparative study of RAPD and ISSR markers to assess the genetic diversity of betel vine (Piper betel L.) in Orissa. Am. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1(2), 200–211 (2011).

Punuri, J. B., Sharma, P., Sibyala, S., Tamuli, R. & Utpal, B. Piper Betle mediated green synthesis of biocompatible gold nanoparticles distinctions in the plant-bacterium signalling processes. Int. Nano Lett. 37, 395–412 (2012).

Anjun &Chandra. Endophytic bacteria: Optimizaton of isolation procedure from various medicinal plants and their preliminary characterization. Asian J. Pharmaceut. Clin. Res. 8(4), 233–238 (2015).

Sharaf, E. M., Hassan, AL-Salmi, A., Fawziah A., Albalwe, F. M., Albalawi, H. R., Darwish, Doaa B. & Eman, F. Synergistic antibacterial activity of compact silver/magnetite core-shell nanoparticles core shell against Gram-negative foodborne pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022).

Sharma, M. & Mallubhotla, S. Diversity, antimicrobial activity, and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of endophytic bacteria sourced from Cordia dichotoma L. Front. Microbial. 13, e879386 (2022).

Compean, K. L. & Ynalvez, R. A. Antimicrobial activity of plant secondary metabolites: A review. Res. J. Med. Plants 8(5), 204–213 (2014).

Li, X., Wang, Z.-G., Chen, H.-H. & Liu, S.-G. The antiÂoxidant methyl 3-(3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hyÂdroxyÂphenÂyl)propionate. Acta Crystallographica Sect. C 70, 1050–1053 (2014).

Ortiz, A. & Sansinenea, E. Phenylpropanoid derivatives and their role in plants’ health and as antimicrobials. Curr. Microbiol. 80, 380 (2023).

Johnson, J. B. et al. A review of vitamin D and its precursors in plants and their translation to active metabolites in meat. Food Rev. Int. 39(4), 1770–1798 (2021).

Riaz, M. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-induced mitigation of heavy metal phytotoxicity in metal contaminated soils: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 402, 123919 (2020).

Goracci, G., Balestrieri, M.L., Nardicchi, V. Metabolism and functions of platelet-activating factor (PAF) in the nervous tissue. In (eds. Lajtha, A., Tettamanti, G. & Goracci, G.) Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology 311–352 (2009).

Lazazzara, V. et al. Growth media affect the volatilome and antimicrobial activity against Phytophthora infestans in four Lysobacter type strains. Microbiol. Res. 201, 52–62 (2017).

Men, S. & Boutté, Y. Sterols in growth and development of plant membranes. Plant Cell Rep. 37(7), 891–906 (2018).

Kishor, P. V. K., Kumari, P. H., Sunita, M. S. L. &Sreenivasula, N. Role of proline in cell wall synthesis and plant development and its implication in plant ontogeny. Front. Plant Physiol. 6 (2015).

Bates, P. D. & Browse, J. The significance of different diacylgycerol synthesis pathways on plant oil composition and bioengineering. Front. Plant Sci. 3 (2012).

Corpas, F. J., Gonzalez-gordo, S. & Palma, J. M. Protein nitration : A connecting bridge between nitric oxide (NO) and plant stress. Sci. Direct 2, 100026 (2021).

Minen, R. I. et al. Structural determinants of sugar alcohol biosynthesis in plants: The crystal structures of mannose-6-phosphate and aldose-6-phosphate reductases. Plant Cell Physiol. 63(5), 658–670 (2022).

Arunachalam, C. & Gayathri, P. Studies on bioprospecting of endophytic bacteria from the medicinal plant of Andrographis paniculata for their antimicrobial activity and antibiotic susceptibility pattern. Int. J. Curr. Pharmaceut. Res. 2(4), 63–68 (2010).

Schulz, B., Römmert, A. K., Dammann, U., Aust, H. J. & Strack, D. The endophyte-host interaction: A balanced antagonism?. Mycological Res. 103(10), 1275–1283 (1999).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215(3), 403–410 (1990).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. BMC Bioinform. 5(1), 113 (2004).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7), 3022–3027 (2021).

Adeyemi, M. A. et al. Pytochemical analysis and GC-MS determination of Lagenaria breviflora R. fruit. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 9(7), 1045–1050 (2017).

Perez, F. et al. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 51(10), 3471–3484 (2007).

Pieterse, C. M., Van der Does, D., Zamioudis, C., Leon-Reyes, A., & Van Wees, S. C. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 28, 489–521 (2012).

Brusa, C., Muzard, M., Rémond, C. & Plantier-Royon, R. β-Xylopyranosides: synthesis and applications. RSC Adv. 110(5), 91026–91055 (2015).

Browse, J. Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 60, 183–205 (2009).

Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. This paper details the phenylpropanoid pathway and the role of related compounds in plant secondary metabolism. Mol. Plant 3(1), 2–20 (2010).

Wasternack, C. & Hause, B. Jasmonates: biosynthesis, perception, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot. 111(6), 1021–1058 (2013).

Mudge, S., Meier-Augenstein, W., Eadsforth, C. & DeLeo, P. What contribution do detergent fatty alcohols make to sewage discharges and the marine environment? J. Environ. Monit. 12(10), 1846–1856 (2010).

Lafuente, M., Rodríguez González-Herrero, M. E., Romeo Villadóniga, S. & Domingo, J. C. Antioxidant Activity and Neuroprotective Role of Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA) Supplementation in Eye Diseases That Can Lead to Blindness: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants 10(3), 386 (2021).

Ali, I. et al. In vitro antifungal activity of hydroxychavicol isolated from Piper betle L. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 9, 7 (2010).

Clouse, S. D. & Sasse, J. M. Brassinosteroids: Essential Regulators of Plant Growth and Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 49(1), 427–451 (1998).

Dall’Osto, M. & Harrison, R. M. Characterization of indoor airborne particles by using real-time aerosol mass spectro-metry, in preparation (2006).

Vanderstraeten, L. & Van Der, S. Accumulation and transport of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) in plants: current status, considerations for future research and agronomic applications. Front. Plant sci. 8, 38 (2017).

Dorokhov, Y. L., Sheshukova, E. V. & Komarova, T. V. Methanol in Plant Life. Front. Plant sci. 9, 1623 (2018).

Dudareva, N., Negre, F., Nagegowda, D. A. & Orlova, I. Plant volatiles: recent advances and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 25(5), 417–440 (2006).

Kubo, I., Muroi, H. & Himejima, M. Structure - Antibacterial activity relationships of anacardic acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 41(6), 1016–1019 (1993).

Bays HE, Ballantyne CM, Kastelein JJ, Isaacsohn JL, Braeckman RA, Soni PN. Eicosapentaenoic acid ethyl ester (AMR101) therapy in patients with very high triglyceride levels (from the Multi-center, plAcebo-controlled, Randomized, double-blINd, 12-week study with an open-label Extension [MARINE] trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 108(5), 682–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.04.015 (2011).

Kim, S. et al. Chemical Structure and Biological Activities of Secondary Metabolites from Salicornia europaea L. Molecules 26(8), 2252 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Advances in the study of the function and mechanism of the action of flavonoids in plants under environmental stresses. Planta 257, 108 (2023).

Scopes, R. K. Protein Purification (Springer New York, NY, 1994)

Yancey, P. H., Clark, M. E., Hand, S. C., Bowlus, R. D. & Somero, G. N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science 217(4566), 1214–1222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7112124 (1982).

Bhattacharya, C. et al. Evaluation of plant growth promotion properties and induction of antioxidative defense mechanism by tea rhizobacteria of Darjeeling, India. Sci. Rep. 10, 15536 (2020).

Li, H. et al. The Role of Plant Progesterone in Regulating Growth, Development, and Biotic/Abiotic Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(18), 10945 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Effects of marine-derived and plant-derived omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on erythrocyte fatty acid composition in type 2 diabetic patients. Lipids Health Dis. 21, 20 (2022).

Bers, D. M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415(6868), 198–205 (2002).

Li-Beisson, Y. et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arabidopsis Book 11, e0161 (2013).

Ng, C. K. Y., Carr, K., McAinsh, M. R., Powell, B. & Hetherington, A. M. Drought-induced guard cell signal transduction involves sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature 410(6828), 596-599 (2001).

Men, S. & Boutté, Y. Sterols in growth and development of plant membranes. Plant Cell Rep. 37(7), 891–906 (2018).

Al-Muhanna, M. K., Anwar, N., Hasnain, M. S. & Nayak, A. K. Chapter 1 - Synthesis of tailor-made polysaccharides: An overview. In Tailor-Made Polysaccharides in Drug Delivery (eds Nayak, A. K. et al.) 1–27 (Academic Press, 2023).

Munnik, T. & Testerink, C. Plant phospholipid signaling: "in a nutshell". J. Lipid Res. 50(Supplement), 260–265 (2009).

Calderón-Preciado, D. et al. Uptake of microcontaminants by crops irrigated with reclaimed water and groundwater under real field greenhouse conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 18(4), 1028–1031 (2011).

Wu, J. et al. Advances in the study of the function and mechanism of the action of flavonoids in plants under environmental stresses. Planta 257, 108 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The Department of Biotechnology and Food Testing Laboratory at Junagadh Agricultural University, as well as all the faculty, staff, and friends who contributed to the successful completion of the research, have the author’s sincere gratitude and deep debt of gratitude.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ms. V. R. Chavda is the first and main author of the manuscript who has conducted the research as a part of her partial fulfilment for obtaining her master’s degree. Dr. S B. Bhatt was the major guide and corresponding author under whose guidance the entire research work was conducted. Dr. V. R. Umaretiya was an SRF in microbial cell involved in extraction procedure of bioactive compounds and microbial identification. Dr. H. P. Gajera was a Professor and Head, helped in publication process. Dr. S. M. Padhiyar was an SRF in biotech cell mainly involved in DNA isolation, gel electrophoresis, PCR amplifcation, gel elution and purification of the 16S rRNA gene for sequencing. Dr. U. K. Kandoliya was the advisory committee member who helped in metabolomics study. Dr. M. V. Parakhia was the advisory committee member who helped in arrangement of chemicals required for molecular identification of the isolates by 16S rRNA gene sequencing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chavda, V.R., Bhatt, S.B., Umaretiya, V.R. et al. Characterization and metabolomic profiling of endophytic bacteria isolated from Moringa oleifera and Piper betel leaves. Sci Rep 15, 632 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84840-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84840-z