Abstract

To investigate the potential of an MRI-based radiomic model in distinguishing malignant prostate cancer (PCa) nodules from benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)-, as well as determining the incremental value of radiomic features to clinical variables, such as prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level and Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) score. A restrospective analysis was performed on a total of 251 patients (training cohort, n = 119; internal validation cohort, n = 52; and external validation cohort, n = 80) with prostatic nodules who underwent biparametric MRI at two hospitals between January 2018 and December 2020. A total of 1130 radiomic features were extracted from each MRI sequence, including shape-based features, gray-level histogram-based features, texture features, and wavelet features. The clinical model was constructed using logistic regression analysis. Radiomic models were created by comparing seven machine learning classifiers. The useful clinical variables and radiomic signature were integrated to develop the combined model. Model performance was assessed by receiver operating characteristic curve, calibration curve, decision curve, and clinical impact curve. The ratio of free PSA to total PSA, PSA density, peripheral zone volume, and PI-RADS score were independent determinants of malignancy. The clinical model based on these factors achieved an AUC of 0.814 (95% CI: 0.763–0.865) and 0.791 (95% CI: 0.742–840) in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively. The clinical-radiomic nomogram yielded the highest accuracy, with an AUC of 0.925 (95% CI: 0.894–0.956) and 0.872 (95% CI: 0.837–0.907) in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively. DCA and CIC further confirmed the clinical usefulness of the nomogram. Biparametric MRI-based radiomics has the potential to noninvasively discriminate between—BPH and malignant PCa nodules, which outperforms screening strategies based on PSA and PI-RADS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common cancer and the second most deadly cancer in males worldwide1. An early diagnosis of prostate cancer is crucial for improving its prognosis. Currently, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is the most widely used screening approach, while invasive prostate biopsy is still the gold standard for PCa2. However, PSA screening has limitations despite significantly improving the diagnosis of PCa. Clinical studies have shown that PSA testing has a predictive value of 25–40%, with limited specificity and sensitivity, resulting in overdiagnosis and overtreatment3,4. Moreover, many of these lesions are less invasive and their clinical significance remains unclear. PCa is characterized by strong heterogeneity and multifocal features, and treatment decisions are typically based on the lesion with the largest volume or the highest gleason score5. Therefore, early and accurate detection of clinically significant PCa (CsPCa), is important for effective treatment5.

With the continuous advancement of imaging technology, it is possible to enhance the specificity and sensitivity of PSA. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging MRI (mpMRI) has been widely used in the detection and staging of prostate lesions, as well as in guiding prostate biopsies, informing treatment options, and facilitating active surveillance7. Currently, mpMRI plays central role in the diagnostic pathway for suspected PCa8. The Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) has greatly contributed to achieving these goals by enabling reliable identification of CsPCa requiring biopsy and facilitating lesion localization9. The PI-RADS 2.1 serves as the reference for risk stratification of PCa based on mpMRI. Suspected lesions are assigned scores ranging from 1 to 5 based on lesion location and image characteristics10. However, the interpretation of images based on the PI-RADS guidelines remains challenging due to interobserver variability, particularly for PI-RADS-3 lesions. Lesions with a PI-RADS score of 3 or higher usually undergo biopsy. However, PI-RADS-3 corresponds to CsPCa in less than 15% of patients10. Therefore, using mpMRI only to determine which patients should undergo biopsy is suboptimal11. Previous studies have shown that biparametric MRI, with its lower cost, no need of contrast agent, and shorter scanning time, is not inferior to, and even superior to, mpMRI in detecting PCa12,13. Consequently, there is an urgent need for clinical tools that can accurately identify PCa and minimize unnecessary biopsies.

Tumor risk stratification remains a challenging task due to the difficulties in interpreting mpMRI images. Machine learning (ML) has the potential to assist radiologists in assessing the invasiveness of indistinct lesions, reducing variability between observers. Previous studies have demonstrated the successful utilization of ML in prostate volume segmentation, lesion segmentation, and detection14. Accurate segmentation and volume estimation of the prostate can provide valuable information for the diagnosis and clinical treatment of hyperplasia and PCa. This can improve the treatment of hyperplasia, surgical planning and prognosis of PCa. Prostate segmentation is increasingly utilized for the diagnosis of PCa, particularly for MRI transrectal ultrasound (MRI/TRUS) fusion biopsy, as accurate prostate segmentation on MRI images is crucial for the interpretation of MRI/TRUS fusion biopsy results15. In addition to segmentation, prostate volume estimation is a useful indicator, especially in the context of BPH treatment, surgical planning, and PCa prognosis16. ML can serve as a valuable tool to address the high variability among readers in certain areas, such as the transitional zone (TZ). Previous studies have compared ML models with the PI-RADS score in evaluating the performance of lesion classification, but consensus has not been reached17,18,19. Some previous studies have combined the results of the PI-RADS score with ML models to distinguish PCa in a clinical setting, but these approaches still rely on subjective PI-RADS scoring and are not sufficient for clinical practice20,21,22.

Radiomics enables the extraction of high-throughput and quantitative image features from medical images. By employing ML algorithms, the radiomic features can be utilized to construct models that uncover information pertaining to tumor pathophysiology. This, in turn, aids in medical decision-making and enhances diagnostic capabilities. This study aimed to develop a clinical-radiomic model that integrates clinical variables and radiomic features to differentiate between—BPH and malignant PCa nodules.

Materials and methods

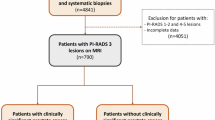

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics committee of Zhongshan City People’s Hospital and the requirement for written informed consent was waived by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan City People’s Hospital. A total of 617 patients with prostatic nodules who underwent contrast-enhanced MRI at two tertiary hospitals between January 2018 and December 2020 were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with histologically confirmed hyperplasia or PCa identified through needle systematic biopsy underwent a technique known as cognitive fusion, in which the urologist performing the biopsy would estimate the location of regions of interest (ROIs) based on the imaging reviewed during the procedure; (2) patients who underwent contrast-enhanced MRI within one week prior to surgery or biopsy and (3) patients who did not receive any preoperative cancer-related treatments, such as radiotherapy, endocrine therapy, or chemotherapy. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) incomplete clinical data (n = 89); (2) patients who received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other treatments before contrast-enhanced MRI scans (n = 157); (3) MRI images with poor quality (n = 51); and (4) cases where the puncture site did not correspond well with the image (n = 69). Finally, 251 patients (mean age, 68.1 ± 9.1 years) were included. The dataset was comprised of two distinct groups: 171 patients from our institution, which were randomly assigned to a training cohort (70%, n = 119; 48 malignant and 71 benign cases) and an internal validation cohort (30%, n = 52; 21 malignant and 31 benign cases); an additional 80 patients from other collaborating hospitals (an external validation cohort: 29 malignant and 51 benign cases). Figure 1 shows the patient recruitment pathway and the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Clinical characteristics

Clinical variables were collected from the medical record system, which mainly consisted of age, prostate volume (PV), PSA value, total PSA (tPSA), free PSA (fPSA), and the ratio of fPSA to tPSA (fPSA/tPSA). Besides, the length, width, and height of the entire prostate and the TZ were measured on the mpMRI. The transverse diameter (A) and anteroposterior diameter (B) of the TZ, as well as the transverse diameter (C) and anteroposterior diameter (D) of the entire prostate, were measured on a horizontal section. The superoinferior diameter of the transition zone (E) and the entire prostate (F) were measured on the sagittal plane. The PV was measured at the boundary of the prostate capsule, and the TZ volume (TZV) was measured at the boundary of the fibrous layer of the TZ. The PV and TZV were calculated as follows: (π/6) × anteroposterior diameter (cm) × transverse diameter (cm) × superoinferior diameter (cm). The peripheral zone volume (PZV) was calculated as the difference between the PV and TZV. PSA density (PSAD) was calculated as tPSA/PV, TZ-PSAD as tPSA/TZV, and PZ-PSAD as tPSA/PZV (or tPSA/PV-TZV).

MR imaging and image interpretation

All patients in the two centers were scanned using a 3.0T MR system (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with a 16-channel Sense Torso XL coil. The protocol included axial, coronal, and sagittal T2-weighted imaging (T2WI), axial T1-weighted imaging (TIWI), axial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), THRIVE, and post-contrast axial breath-hold dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) imaging performed with fat-suppressed e-THRIVE. A total of 20 dynamic enhanced prostate scans were performed, with a scanning time of two minutes. Contrast agent (Gadodiamide, MEDRAD Healthcare, 0.2 mmol/kg body weight) was administered intravenously at the end of the first scan, followed by a 20 ml saline flush at the same rate of 3.0 ml/s. The detailed acquisition parameters are presented in Table 1.

The images were independently evaluated by two radiologists with 8 years of experience in prostate MRI, and by a third radiologist with 10 years of experience in prostate MRI, using the PI-RADS V2.1 criteria. The radiologists were unaware of the histopathology results. In cases of disagreement between the two radiologists, a third radiologist was consulted to reach a consensus on the final PI-RADS V2.1 score. Specially, the descriptors for the third radiologist were moved to where the two radiologists discussed them being the consensus vote. The PI-RADS V2.1 scores were assessed based on the T2WI, DWI, and DCE-MRI sequences. If multiple lesions were present, the PI-RADS V2.1 score was determined based on the largest or most aggressive lesion.

Lesion segmentation

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow of this study. The manual segmentation of the prostatic nodule was carried out by an experienced radiologist (with 8 years of experience in prostatic disease diagnosis) using ITK-SNAP software. The region of interest (ROI) was manually delineated slice-by-slice on axial T2WI and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) images, encompassing the entire suspicious lesions. As for PCa, the entire lesion area, including the peripheral and transitional areas of cancer, was demarcated. As for BPH, the complete hyperplasia area was outlined, while avoiding the surrounding prostate capsule, peripheral blood vessels, seminal vesicle root, bleeding, calcification, and urethra. Afterwards, the delineated ROIs were transformed into three-dimensional volumes of interest (VOIs). To minimize potential bias, the segmentation results were independently validated by a radiologist with 10 years of experience in prostatic disease diagnosis.

Image preprocessing

The N4 correction algorithm in the 3D Slicer software was used to eliminate MRI offset field artifacts and minimize the impact of RF field inhomogeneities and the MRI equipment itself. Then, the grayscale values of the MRI were normalized to a range of 0–255 by applying a min–max scaling technique. This processing step is implemented to mitigate variations in grayscale between different patients, acquisition times, and parameter settings, ensuring precise and dependable texture analysis. Lastly, the B spline interpolation algorithm was used to resample the ROI to a uniform size (1 * 1 * 1).

Radiomic feature extraction

Radiomic features were extracted from the segmented VOI in original images, Laplacian-of-

Gaussian (LoG) filter images, and wavelet filter images using the Pyradiomics v3.0 open source package. For the LoG filter, the sigma parameter was set to emphasize different levels of texture roughness, with sigma values of 1, 3, and 5 used to obtain filtered images with different textures. A bin width of 10 was selected for the wavelet filtering. The types of radiomic features were as follows: (1) shape-based features, (2) gray-level histogram-based features, (3) texture features, including gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), gray-level run length matrix (GLRLM), gray-level size zone matrix (GLSZM), gray-level dependence matrix (GLDM), and neighborhood gray-tone difference matrix (NGTDM), and (4) wavelet features. A total of 1130 radiomic features were extracted from each MRI sequence.

Feature selection and development of radiomic models

Feature selection and model construction were exclusively conducted on the training cohort. Initially, Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) analysis was employed to obtain a feature set with minimal redundancy (correlation coefficient threshold set at 0.99). The yielded radiomic feature values were subsequently normalized using the Z-score. To further improve the model’s generalization ability and avoid overfitting, we ultimately applied the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or Relief algorithm to obtain a subset of stable and reproducible radiomic features. After that, seven ML classifiers were compared to construct the radiomic models, that is, Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Naive Bayes (NB), Adaboost, and XGboost. Five-fold cross-validation was used for feature selection and optimization of the classification algorithm to identify the optimal radiomics model from 14 combinations. The model was evaluated using both the internal validation and external validation cohorts. The radiomic signature (ie, rad-score) was yielded by performing logistic regression analysis on the predicted probabilities generated by the radiomic model.

Combined model construction and evaluation

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify independent risk factors (with both P < 0.05), which were then used to develop a clinical model. The combined model (or clinical-radiomic model) was established and visualized as a nomogram by incorporating significant clinical factors and rad-score based on a stepwise logistic regression model, with the Akaike information criterion (AIC) as the criterion for model selection. The models were developed on the training cohort and verified in both the held-out validation and external validation cohorts. The performance of the combined models was evaluated from three aspects: discrimination, calibration, and clinical validity. The discrimination ability was evaluated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, which included calculations of the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity. Calibration curves with the Hosmer–Lemeshow (H–L) test were applied to assess the goodness of fit between the model-predicted probabilities and the observed event proportions. The clinical usefulness was evaluated using decision curve analysis (DCA) and clinical impact curve (CIC)23. DCA provides a visual representation of the net benefit of the model at various thresholds. The CIC was used to assess the clinical impact of the combined model by estimating the proportion of patients whose treatment plan would be altered based on the predictive results.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the patients were compared between the training and internal validation cohorts. Statistical differences were assessed using the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test for normally distributed or non-normally distributed continuous variables, respectively. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Delong test was used to compare AUCs between models. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Python 3.7. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tis study complied with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan City People’s Hospital. Informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan City People’s Hospital.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 251 patients diagnosed with BPH or PCa were included in the study. Among them, 153 patients (61%) had benign target lesions, with an average age of 67.1 ± 8.8 years. The remaining 98 patients (39%) had malignant target lesions, with an average age of 69.7 ± 9.4 years. Table 2 shows there was no significant difference observed between the training and internal validation cohorts (all P > 0.05).

Clinical and radiomic models

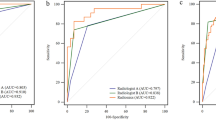

Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed that PSA level (P = 0.004), fPSA (P = 0.044), fPSA/tPSA (P = 0.006), PZV (P = 0.024), PSAD (P = 0.001), TZ-PSAD (P = 0.001), PZ-PSAD (P = 0.031), and PI-RADS score (P = 0.002) were identified as potential factors. After multivariate analysis, fPSA/tPSA (P = 0.045), PZV (P = 0.041), PSAD (P = 0.002), and PI-RADS score (P = 0.003) were determined to be independent risk factors for malignant nodules. The clinical model was constructed based on these independent factors achieved an AUC of 0.857 (95%CI: 0.812- 0.902) in the training cohort, 0.814 (95%CI: 0.763–0.865) in the internal validation cohort, and 0.791 (95% CI: 0.742–840) in the external validation cohort (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Performance of clinical, radiomic, and clinical-radiomic models for the diagnosis of malignant prostate nodules. (a) T2WI radiomic model and ADC radiomic model based on various combinations of feature selection and classification methods. (b–d) ROC curves of the clinical model, radiomic model, and clinical-radiomic model in the training cohort, internal validation cohort, and external validation cohort, respectively.

A total of 705 radiomic features derived from T2WI images were retained after PCC analysis. The optimal T2WI-based radiomic model was constructed by combining the RFE filter and Adaboost classifier, utilizing 12 selected features (Table 4). In the internal and external validation cohorts, the T2WI radiomic model yielded an AUC of 0.825 (95% CI: 0.768–0.882) and 0.753 (95% CI: 0.700–0.806), respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Similarly, for ADC-derived features, 706 features were preliminarily screened by PCC analysis. The best-performing ADC-based radiomic model was built by combining the Relief filter and LDA classifier, using 16 selected features (Table 4). This combined model achieved an AUC of 0.896 (95% CI: 0.859–0.933) and 0.818 (95% CI: 0.773–0.863) in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively. The fusion radiomic model, which integrated T2WI and ADC rad-scores, obtained a higher accuracy with an AUC of 0.908 (95% CI: 0.871–0.945) and 0.841 (95% CI: 0.800–0.882) in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Evaluation of the clinical-radiomic model

Multivariate analysis using the stepwise regression method was conducted on fPSA/tPSA, PZV, PSAD, PI-RADS score, and fusion rad-score. The results demonstrated that fPSA/tPSA (P = 0.023), PSAD (P = 0.016), PI-RADS score (P = 0.048), and fusion rad-score (P = 1.38e-07) were identified as independent risk factors (Table 5). The clinical-radiomic nomogram was developed using the following formula:

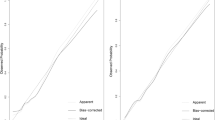

\(- \,{4}.{541}\, - \,{5}.{512}\,*\,{\text{fPSA}}/{\text{TPSA}}\, + \,0.{996}\,*\,{\text{PSAD}}\, + \,0.{546}\,*\,{\text{PI}} - {\text{RADSscore}}\, + \,{5}.{785}\,*\,{\text{fusion }}\,{\text{rad - score}}\)The combined model produced an AUC of 0.925 (95% CI: 0.894–0.956) and 0.872 (95% CI: 0.837–0.907) in the internal and external validation cohorts, respectively (Table 3). In the internal validation cohort, the sensitivity and specificity values were 76.2% and 90.3%, while in the external validation cohort, they were 82.8% and 76.5% (Table 3). The calibration curves suggested strong concordance between the predicted probabilities from the model and the actual event proportions in both the internal validation cohort (H–L test, P = 0.476) and the external validation cohort (H–L test, P = 0.210) (Fig. 4). The higher position of our model’s curve relative to the “All” line across a wide range of threshold probabilities in Fig. 5a indicates a more accurate discrimination between those who will benefit from the intervention and those who will not. CIC plot in Fig. 5b showed that at the selected risk threshold of 0.49, ∼419 out of 1000 patients were considered to have a high risk of developing disease progression and ∼310 developed disease progression. The results further confirmed the clinical usefulness of the nomogram.

Dicussion

In this current study, we developed multiple models for diagnosing malignant prostate nodules, including a clinical model, ADC-radiomic model, T2WI-radiomic model, fusion radiomic model, and clinical-radiomic model. Ultimately, the clinical-radiomic model, which incorporated fPSA/tPSA, PSAD, PI-RADS score, and fusion rad-core (combining ADC and T2WI-based rad-score), demonstrated the highest performance. The model yielded an AUC of 0.925, sensitivity of 76.2%, and specificity of 90.3% in the internal validation cohort. In the external validation cohort, the combined model achieved an AUC of 0.872, sensitivity of 82.8%, and specificity of 76.5%.

Several studies have used clinical, radiological, or radiomic features to diagnose prostate lesions. However, consensus on clinical and radiographic indicators has not been reached in previous studies8,9,17,18,19,20,21,22. This lack of consensus may be attributed to different target populations, random sampling bias, and limited sample sizes. In our work, we have identified four clinico-radiological features that aid in diagnosing PCa, which can help mitigate overdiagnosis and overtreatment24,25. Accumulated evidence suggests that tumors derived from the TZ exhibit distinct cytohistological characteristics, resulting in a lower incidence of Gleason score, prostate extravasation, seminal vesicle invasion, and biochemical recurrence in this region26,27,28,29,30. TZ-PSAD is calculated using a comprehensive formula that includes PSA, TZV, and PZV. Aurelia F et al. concluded that TZ-PSAD was more closely associated with tumor aggressiveness than PSAD31. In our study, TZ-PSAD had higher diagnostic efficiency compared to PSAD and PZ-PSAD. PI-RADS is a standardized MRI assessment method widely utilized for evaluating prostate lesions and is highly effective in diagnosing PCa32. While the PI-RADS score is commonly used in clinical practice, it cannot be used as the sole basis for biopsy or follow-up evaluation. The PI-RADS score exhibits advantages in diagnosing CsPCa, but its accuracy is dependent on observer experience and expertise. Therefore, relying solely on the PI-RADS score for predicting biopsy results has certain limitations33.

With the advancements in computer-assisted methods, radiomic analysis has been employed to diagnose prostate lesions. MRI allows for multimodal and multidirectional evaluation of prostate lesions. MRI can provide a more comprehensive description of soft tissue characteristics, atomic density, and lesion enhancement compared to CT. Contrast enhanced imaging can offer additional functional information. Min et al. utilized radiomic signature to differentiate between CsPCa and clinically insignificant PCa34. Woźnicki et al. added the PI-RADS score into a radiomic model for PCa detection and classification20. Despite the high diagnostic performance of the final models derived from these studies, achieving standardization and uniformity remains challenging due to the diversity of research methods. This is one of the major obstacles currently faced by radiomics. Until the issue of standardization is resolved, widespread implementation of radiomics for disease diagnosis will be highly challenging.

Optimizing the diagnostic efficacy of the radiomic model is crucial for accurately identifying BPH and PCa—lesions preoperatively, which holds great significance for PCa patients and directly impacts the disease prognosis. The primary advantage of radiomics lies in its ability to reduce subjectivity and reliance on empirical knowledge, enabling efficient automatic identification of benign and malignant prostate nodules. To construct the radiomic model, only MRI images and other relevant variables are required as inputs. This remarkable efficacy, coupled with high efficiency, serves as the primary driving force behind the integration of artificial intelligence in the field of medicine. Additionally, we assessed the added value of clinical variables and radiological features to the fusion radiomic model based on T2WI and ADC, and the results were satisfactory. This indicates that the explainable features utilized in routine clinical practice provide valuable information for diagnosing PCa.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, due to its retrospective design, patients who were clinically suspected to have “malignant nodules” in the prostate but did not undergo needle biopsy were excluded, which may introduce potential selection bias and compromise the reproducibility and comparability of the results. Larger cohorts are needed to validate our findings. Second, the Glesson score was not considered in this study, but it is the focus of our future research. Third, this study only analyzed several commonly used dimensionality reduction modeling methods and did not comprehensively investigate existing dimensionality reduction modeling methods.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have established several models for preoperative diagnosis of prostate lesions and have compared the diagnostic effects of these models, thereby providing a preferred method for clinical application. Additionally, we have derived an optimal rad-score for the clinical-radiomic nomogram. This study not only demonstrates the feasibility of applying radiomics to noninvasive preoperative diagnosis of the prostate but also aims to determine the best modeling method and systematic research approach in radiomic research, thereby providing a foundation for the standardization of radiomics. Moving forward, further relevant studies are needed to explore the standardization of radiomics, enabling the translation of radiomics as a non-invasive and useful tool into clinical practice.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- PI-RADS:

-

Prostate imaging reporting and data system

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PCa:

-

Prostate cancer

- CsPCa:

-

Clinically significant PCa

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- TRUS:

-

Transrectal ultrasound

- TZ:

-

Transitional zone

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic curves

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- CIC:

-

Clinical inpact curve

- mpMRI:

-

Multiparametric magnetic resonance

- PV:

-

Prostate volume

- tPSA:

-

Total PSA

- fPSA:

-

Free PSA

- fPSA/tPSA:

-

Ratio of fPSA to tPSA

- PZV:

-

Peripheral zone volume

- PSAD:

-

PSA density

- T2WI:

-

T2-weighted imaging

- TIWI:

-

T1-weighted imaging

- DWI:

-

Diffusion-weighted imaging

- DCE:

-

Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging

- ADC:

-

Apparent diffusion coefficient

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- BPH:

-

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

- VOIS:

-

Volumes of interest

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73(1), 17–48 (2023).

Merdan, S. et al. Toward better use of bone scans among men with early-stage prostate cancer. Urology 84(4), 793–798 (2014).

Andriole, G. L. et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 360(13), 1310–1319 (2009).

Hamdy, F. C. et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(15), 1415–1424 (2016).

Arora, R. et al. Heterogeneity of Gleason grade in multifocal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer 100(11), 2362–2366 (2004).

van den Bergh, R., Loeb, S. & Roobol, M. J. Impact of early diagnosis of prostate cancer on survival outcomes. Eur. Urol. Focus 1(2), 137–146 (2015).

Stabile, A. et al. Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer diagnosis: current status and future directions. Nat. Rev. Urol. 17(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0212-4 (2020).

Kasivisvanathan, V. et al. MRI-targeted or standard biopsy for prostate-cancer diagnosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 378(19), 1767–1777. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801993 (2018).

Cuocolo, R. et al. Clinically significant prostate cancer detection on MRI: A radiomic shape features study. Eur. J. Radiol. 116, 144–149 (2019).

Turkbey, B. et al. Prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2.1: 2019 update of prostate imaging reporting and data system version 2. Eur. Urol. 76(3), 340–351 (2019).

Santoro, A. A. et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging of the prostate: Lights and shadows. Urol. J. 88(4), 280–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/03915603211019982 (2021).

Greenberg, J. W. et al. A narrative review of biparametric MRI (bpMRI) implementation on screening, detection, and the overall accuracy for prostate cancer. Ther. Adv. Urol. 14, 175 (2022).

Wallstrom, J. et al. Bi- or multiparametric MRI in a sequential screening program for prostate cancer with PSA followed by MRI? Results from the Goteborg prostate cancer screening 2 trial. Eur. Radiol. 31(11), 8692–8702 (2021).

Cutaia, G. et al. Radiomics and prostate MRI: current role and future applications. J. Imaging 7(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging7020034 (2021).

Sparks, R., Bloch, B. N., Feleppa, E., Barratt, D. Madabhushi, A. Fully automated prostate magnetic resonance imaging and transrectal ultrasound fusion via a probabilistic registration metric. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 8671 (2013).

Lim, K. B. Epidemiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J. Urol. 4(3), 148–151 (2017).

Ushinsky, A. et al. A 3D–2D hybrid U-net convolutional neural network approach to prostate organ segmentation of multiparametric MRI. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 216(1), 111–116 (2021).

Mehrtash, A., Sedghi, A., Ghafoorian, M., Taghipour, M., Tempany, C. M., Wells, W. M. et al. Classification of clinical significance of MRI prostate findings using 3D convolutional neural networks. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 10134 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Prostate cancer differentiation and aggressiveness: Assessment with a radiomic-based model vs. PI-RADS v2. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 49(3), 875–884 (2019).

Woźnicki, P. et al. Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer characterization: combined use of radiomics model with PI-RADS and clinical parameters. Cancers 12(7), 1767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071767 (2020).

Bernatz, S. et al. Comparison of machine learning algorithms to predict clinically significant prostate cancer of the peripheral zone with multiparametric MRI using clinical assessment categories and radiomic features. Eur. Radiol. 30(12), 6757–6769 (2020).

Litjens, G. J., Barentsz, J. O., Karssemeijer, N. & Huisman, H. J. Clinical evaluation of a computer-aided diagnosis system for determining cancer aggressiveness in prostate MRI. Eur. Radiol. 25(11), 3187–3199 (2015).

Alba, A. C. et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA 318(14), 1377–1384 (2017).

Benson, M. C. et al. Prostate specific antigen density: a means of distinguishing benign prostatic hypertrophy and prostate cancer. J. Urol. 147(3 Pt 2), 815–816 (1992).

Stefano, D. L. et al. Prostate health index and prostate cancer gene 3 score but not percent-free prostate specific antigen have a predictive role in differentiating histological prostatitis from PCa and other nonneoplastic lesions (BPH and HG-PIN) at repeat biopsy. Urol. Oncol. 424e(33), 17–23 (2015).

Grignon, D. J. & Sakr, W. A. Zonal origin of prostatic adenocarcinoma: Are there biologic differences between transition zone and peripheral zone adenocarcinomas of the prostate gland?. J. Cell Biochem. Suppl. 19, 267–269 (1994).

McNeal, J. E. Cancer volume and site of origin of adenocarcinoma in the prostate: Relationship to local and distant spread. Hum. Pathol. 23(3), 258–266 (1992).

McNeal, J. E., Redwine, E. A., Freiha, F. S. & Stamey, T. A. Zonal distribution of prostatic adenocarcinoma. Correlation with histologic pattern and direction of spread. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 12(12), 897–906 (1988).

Steuber, T. et al. Transition zone cancers undermine the predictive accuracy of Partin table stage predictions. J. Urol. 173(3), 737–741 (2005).

Shannon, B. A., McNeal, J. E. & Cohen, R. J. Transition zone carcinoma of the prostate gland: a common indolent tumour type that occasionally manifests aggressive behavior. Pathology 35, 467–471 (2003).

Schneider, A. F. et al. Comparison of PSA-density of the transition zone and whole gland for risk stratification of men with suspected prostate cancer: A retrospective MRI-cohort study. Eur. J. Radiol. 120, 108660 (2019).

Bjurlin, M. A. et al. Update of the standard operating procedure on the use of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis, staging and management of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 203(4), 706–712 (2020).

Wei, X. et al. Diagnostic value of combining PI-RADS v2.1 with PSAD in clinically significant prostate cancer. Abdom. Radiol. 47(10), 3574–3582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-022-03592-4 (2022).

Min, X. et al. Multi-parametric MRI-based radiomics signature for discriminating between clinically significant and insignificant prostate cancer: Cross-validation of a machine learning method. Eur. J. Radiol. 115, 16–21 (2019).

Funding

Yang-Bai Lu was supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515220032), Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Foundation (B2023195, 2023B3006),Science and Technology Project of Zhongshan City (2020B1073), Zhongshan city people’s hospital Major Project of Scientific Research Foundation (BG20228249) and Zhongshan City People’s Hospital Outstanding Youth Project (SG2023106). Yong-xin Zhang was supported by Science and Technology Project of Zhongshan City (2020B1070).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantors of integrity of entire study, Y.-X.Z. andY.-B.L.; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; approval of final version of submitted manuscript, all authors; clinical studies, Y.-B.L., Z.-Q.L., Y.-X.Z,, Z.-Y.L., R.-Q.Y and H.-X.H.; Acquisition of data: Y.-B.L.,Y.S,Q.L., R.-Q.Y and A.Y.. Sequence debugging and data processing Y.-B.L. , X.-H.X, and Y.-X.Z

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tis study complied with the declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan City People’s Hospital. Informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective nature of the study and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan City People’s Hospital.

Consent for publication

Publication was approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, Y., Yuan, R., Su, Y. et al. Biparametric MRI-based radiomics for noninvastive discrimination of benign prostatic hyperplasia nodules (BPH) and prostate cancer nodules: a bio-centric retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 654 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84908-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84908-w