Abstract

We aimed to investigate the synergistic effects of colistin and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles on the biofilm formation and expression of Quorum Sensing regulated and related genes in clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. Ten clinical P. aeruginosa isolates collected from patients with burn wound infections were investigated. The antibiotic sensitivity pattern of the isolates was determined using disk diffusion and microbroth dilution tests. The silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized using propolis and characterized. The microtiter plate method and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were used to evaluate the synergistic effects of colistin and silver nanoparticles combination (AgNPs@CL) on the inhibition of biofilm formation. The effect of AgNPs@CL on the expression of genes controlled by QS was evaluated using RT-PCR. All isolates were strong biofilm formers. Confronting AgNPs@CL, all isolates were either synergistic or additive and effectively decrease the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC) values of Carbapenem-Resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA) isolates. The SEM analysis corroborated the enhanced biofilm inhibition observed with the combined treatment compared to individual AgNPs or colistin treatments. When exposed to AgNPs@CL, the expression levels of lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pelA, and pslA genes significantly decreased in P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 and clinical isolate No. #354, which displayed synergistic activity. In contrast, with additive activity, clinical isolate No. #30 showed no significant decrease. Targeting critical components of QS could effectively inhibit biofilm production. The results of our study suggest AgNPs@CL as an auxiliary to antibiotic therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Burn injuries are a significant global health issue, affecting approximately 11 million people annually1. These injuries can lead to long-term disability or death, with wound infections being a common and serious complication that can hinder healing and increase the risk of sepsis and mortality2. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a well-known pathogen linked to burn wound infections. Its ability to form biofilms complicates treatment by shielding the bacteria from the immune system and antibiotics. Biofilm-associated infections are challenging to eradicate and often require prolonged and aggressive antibiotic therapy3,4,5.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses quorum sensing (QS) to regulate virulence and biofilm formation through signaling molecules called autoinducers6,7. The bacterium has multiple QS systems, including Las, Rhl, and PQS (Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal)7,8. The Las system, activated by 3OC12-HSL, controls virulence factor expression. The Rhl system, regulated by C4-HSL, is crucial for biofilm development and immune evasion9. The PQS system interacts with Las and Rhl to modulate virulence and enhance biofilm stability7,9. The genes pelA and pslA are involved in the production of the EPS that form the biofilm matrix. Both PelA and PslA polysaccharides are crucial for the initial attachment of bacterial cells to surfaces and for the maintenance of biofilm architecture8,10.

P. aeruginosa is a versatile pathogen with intrinsic and acquired antibiotic resistance mechanisms, including efflux pumps, mutations in antibiotic targets, biofilm formation, and antibiotic-modifying enzymes. These mechanisms work together to make P. aeruginosa difficult to treat in clinical settings11,12,13,14.

The combination of efflux pumps, mutations, biofilm formation, and specific resistance determinants in P. aeruginosa leads to its strong resistance profile, highlighting the need for innovative therapeutic strategies and alternative methods to effectively combat this pathogen. Promising options include photodynamic therapy, combination therapy, and repurposing existing drugs15,16,17,18.

Colistin (CL) is a last-resort antibiotic used to treat infections caused by Carbapenem-Resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA)19. It works by interacting with bacterial cell membranes, targeting the lipopolysaccharide layer of Gram-negative bacteria20. This disrupts the outer membrane’s integrity by displacing stabilizing divalent cations21. Colistin’s strong antibacterial properties are important in treating multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, but its potential nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity are drawbacks. It is often used in combination with other antibiotics to enhance effectiveness and reduce resistance development22,23,24.

Combining nanoparticles with antibiotics is a widely applied strategy to enhance the efficacy of drugs while reducing their required dose25,26. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) affect several vital functions within P. aeruginosa, including DNA replication, respiratory chain reactions, signal transduction, and membrane integrity27.

Green synthesis of AgNPs using natural products like propolis is increasingly gaining attention due to its eco-friendliness and biocompatibility. Studies by Gurunathan et al.28 and Ahmed et al.29 have reported on the successful synthesis and potent antibacterial activity of green-synthesized AgNPs. Propolis is a resinous biomaterial made by honeybees. It contains a complex composition of plants’ secondary metabolites, which can serve as both reducing and stabilizing agents in the AgNPs preparation process30,31,32. Propolis is recognized for its potent antimicrobial properties against bacteria, fungi, and viruses, attributed to its rich content of flavonoids and phenolic acids. These compounds disrupt microbial cell walls and membranes, inhibit essential enzymes and proteins involved in microbial metabolism, and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative stress and lead to microbial cell death33,34. Furthermore, propolis contains phenolic compounds that can disrupt biofilm formation by inhibiting quorum sensing pathways, breaking down the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix, and reducing bacterial adhesion to surfaces35,36.

This study introduces a novel synergistic approach to combating MDR P. aeruginosa biofilms by leveraging green-synthesized AgNPs using propolis. Our study uniquely demonstrates the combined impact of AgNPs and CL on biofilm inhibition and QS suppression in an extremely resistant clinical setting. The isolates were all MDR, highly resistant to CL, and derived from intensive care units (ICUs) burn patients, making their resistance profile particularly rare and clinically challenging. Moreover, our study targets a distinct set of QS and biofilm-associated genes (lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pelA, pslA). We hypothesized that this combination would reduce gene expression and, as a result, decrease biofilm production.

Materials and methods

Isolation and identification of P. aeruginosa

A total of 39 swab samples were taken from burn patients’ wounds who were admitted to the ICUs in Hamadan, located in western Iran. Among these samples, 10 P. aeruginosa isolates were chosen for further study. Samples were collected from non-duplicate patients using sterile swabs and placed into Amies transport medium (without charcoal) (Merck, Germany) to maintain bacterial viability during transportation. The samples were transported to the laboratory under controlled conditions (4–8 °C) within 2–4 h to minimize bacterial overgrowth or degradation. Upon arrival, the samples were cultured on selective and differential media for bacterial isolation and further analysis. Upon arrival, the collected samples were cultured on blood agar (Merck, Germany), MacConkey agar (Merck, Germany), and cetrimide agar (Merck, Germany) and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. The grown colonies were examined for morphology, pigment production, characteristic grape-like odor, and Gram staining. The lactose-negative bacteria were purified for confirmatory tests. Growth at 42 °C, catalase and oxidase tests, Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) test (Merck, Germany), urease test (Merck, Germany), Simmons Citrate agar test (Merck, Germany), and oxidative/fermentative media (Merck, Germany) were used to confirm the P. aeruginosa isolates37,38.

The P. aeruginosa isolates were chosen based on their resistance to CL and carbapenems, MDR susceptibility pattern, and ability to produce a strong biofilm. Two clinical isolates were selected as representatives for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis based on their response to AgNPs@CL, and phylogenetic profile. The control strain for all experiments was P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853.

Ethics approval

-

The Hamadan University of Medical Sciences ethics committee approved the current research with the following code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1400.255. Regular oversight was conducted to ensure compliance with ethical standards.

-

Patient identities remained anonymous throughout the study. Each sample was assigned a unique code, and no identifiable patient information was linked to the results. Data were stored securely and were accessible only to authorized researchers.

-

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to ethical regulations for research involving human subjects.

-

The sample collection was non-invasive and performed using sterile swabs, posing minimal risk to participants. No additional interventions or procedures were needed beyond standard clinical care.

-

Patients were provided with information about the study goals, possible advantages, and their ability to withdraw at any point without impacting their medical care. Each participant completed a written informed consent form prior to sample collection.

Phylogenetic analysis of P. aeruginosa isolates

Multiple-Locus Variable Number of Tandem Repeats Analysis (MLVA) was performed to reveal the clonal relatedness of isolates based on the methods described by Vu-Thien et al.39. Ten loci containing tandem repeats were amplified using conventional PCR with the primer pairs listed in Table 1. The amplified VNTRs (Variable Number of Tandem Repeats) were subsequently separated by electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel (Sigma, USA). To assign the copy numbers to their corresponding loci, the amplicons were divided by the repeat units after subtracting the weight of the flanking region. The similarity dendrogram and Minimum Spanning Tree (MSTree) were constructed based on the UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) algorithm using the BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Belgium). Colored partitioning was used to separate isolates that were identical in all loci except for two in the MSTree.

Green synthesis and characterization of AgNPs

In this study, propolis extract was used for the synthesis of AgNPs. First, the propolis was cleaned with water and dried at 60 °C for 48 h. The green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using propolis extract was carried out following a previously established protocol for AgNP synthesis using pomegranate peel extract, with brief modifications40. A hydroalcoholic extract of propolis was obtained by dissolving 50 g of the sample in 500 mL of 70% ethanol at room temperature for 72 h. The resulting extract was filtered using Whatman No. 40 filter paper, and the fine suspended powder particles were separated through centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. To synthesize AgNPs, a fresh solution of silver nitrate (10 µg/mL) (Merck, Germany) was prepared. These modifications were optimized to ensure the stability and efficiency of AgNP synthesis with propolis extract. The propolis extract was gradually added to the silver nitrate solution, followed by stirring for 2 h at 70 °C. The appearance of a blue-grey hue in the solution indicated the successful synthesis of AgNPs. The obtained sediment was washed with Double Distilled Water (DDW) and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min to obtain the final product40,41. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) (Philips EM 208 S) was performed to discern AgNPs’ morphology and size. GraphPad Prism 8.0 and ImageJ software were used to determine the size distribution of AgNPs. The chemical properties of AgNPs were analyzed through X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Philips PW 1730 diffractometer) pattern, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra (Bruker ALPHA II FTIR Spectrometer, USA), UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Specord 210 plus, Analytik, Jena, Germany), and zeta potential value (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instrument, UK).

MTT assay

The MTT assay was conducted to evaluate the impact of green-synthesized AgNPs on cell viability, an important factor in determining the cytotoxic threshold of AgNPs. Assessing the impact of AgNPs on cell viability is essential to ensure that their antibacterial effects do not harm host cells. The assay quantified cell viability post-treatment with AgNPs, offering valuable data on the safety and effectiveness of the therapy. Murine L929 fibroblast cell lines, obtained from the National Cell Bank (Pasture Institute, Iran), were cultured in DMEM medium (BioIdea, Iran) supplemented with glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco). Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To investigate the exposure effects of AgNPs on cell viability, cells at a density of 1 × 104 per 96-well plate were exposed to serial dilutions of AgNPs at final concentrations ranging from 0.036 µg/mL to 150 µg/mL. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with 100 µL of MTT solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), followed by a 1 h incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The MTT solution was discarded, and 100 µL of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (DNAbiotech, Iran) was added to each well. The optical density of each well was recorded at 550 nm. The viability percentage was then calculated by Absorbance of test/Absorbance of control × 100. The IC50 value was determined as 50% of the percentage of cell viability. The unpaired t-test using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) assessed differences between the IC50 value-containing and control groups42,43,44.

Antibiotic susceptibility assay

The standard Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method45 was performed using a selected set of disks (Conda, Pronasida, Spain) except for ceftazidime, which was from Rosco in Denmark. The set of disks included Ceftazidime (30 µg), Cefepime (30 µg), Aztreonam (30 µg), Meropenem (10 µg), Imipenem (10 µg), Amikacin (30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Piperacillin-tazobactam (100/10 µg), and Gentamicin (10 µg). Briefly, bacterial suspensions were standardized to a 0.5 McFarland standard and evenly spread on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Merck, Germany) using a sterile swab. Antibiotic disks were placed on the plates and incubated at 35 °C for 18 h. The zones of inhibition were measured, and the results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2024 guidelines46.

Microbroth Dilution test

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) of colistin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) and AgNPs were determined based on the CLSI 2024 guidelines46. A stock solution of colistin sulfate was prepared according to CLSI recommendations. Then, 100 µL of the two-fold serially diluted stock solution, prepared in Mueller Hinton broth (Merck, Germany), was inoculated with 100 µL of each tested isolate at a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. Colistin resistance was determined for strains with MIC values ≥ 446. The same procedure was used to determine the AgNPs MIC. The AgNP powder was dissolved in distilled water to make a stock solution of 300 µg/mL. This solution was then diluted in Mueller Hinton broth to create the required concentrations for MIC determination. The preparation method ensured uniformity and sterility, ensuring consistency in all experiments. The experiments were conducted in triplicate. Both positive (growth control) and negative controls (sterile broth without bacterial inoculation) were taken into account in all the experiments.

Growth Inhibition by checkerboard synergy test

In order to investigate the synergistic effects of colistin and AgNPs, two-fold dilutions of each were used in the two-dimensional checkerboard assay47,48. Four dilutions lower and two higher than the MIC values of colistin and AgNPs for each isolate were used in a double-strength Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Merck, Germany) using a 96-well polystyrene microplate. The initial concentration of colistin and AgNPs was four times the desired final concentration of each. Rows 1 to 8 were loaded with 50 µL of each concentration of AgNPs, and columns 1 to 11 with each concentration of colistin. Eventually, wells were inoculated with 100 µL of 5 × 105 CFU/mL of each isolate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MIC for each agent alone and in combination is determined by identifying the lowest concentration that inhibits visible growth. The Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC) and FIC index (FICi) of colistin and AgNPs were determined for each isolate as follows:

FIC of AgNPs was calculated in a similar manner. The FIC index (FICi) for each isolate was calculated as follows47:

To categorize the isolates based on their reaction to the combined treatment (AgNPs@CL), the following rules were established49: FICi of ≤ 0.5, synergism; FICi of 0.5 to 4, additivity/indifference; and FICi > 4, antagonism.

Microtitre plate method for biofilm formation assessment

96-well tissue-treated flat-bottomed plates were used to determine the amount of biofilm produced among isolates based on the protocol described by Stepanovic et al.50. All isolates were cultured on nutrient agar (Merck, Germany) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. 20 µL of 0.5 McFarland-adjusted suspension was diluted in 180 µL of fresh LB broth and loaded into wells, followed by overnight incubation at 37 °C. The negative control wells contained only LB broth. Wells were rinsed thrice with normal saline, fixed with 150 µL of methanol for 20 min, and stained with 200 µL of 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min at room temperature. Wells were rinsed thrice with normal saline again to remove excess dye, then incubated with 200 µL of 95% ethanol for 20 min. The optical density (OD) of each well was measured at 570 nm using a microtitre plate reader (ChroMate 4300). All tests were performed in triplicate. Based on the following criteria, isolates were categorized into four groups. OD cutoff = Mean OD of negative control + (3 × Standard Deviation of negative control). Mean OD ≤ OD cutoff = no biofilm producer; OD cutoff < Mean OD ≤ 2 × OD cutoff = weak biofilm producer; 2 × OD cutoff < Mean OD ≤ 4 × OD cutoff = moderate biofilm producer; 4 × OD cutoff < Mean OD = strong biofilm producer50.

Biofilm Inhibition assay

To determine the minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration (MBIC), P. aeruginosa isolates were grown in LB broth for 18 h at 37 °C. Bacterial cells were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm; pellets were washed with sterile Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) thrice, followed by resuspension in LB broth to achieve an optical density of 1 × 107 CFU/mL. Based on the results of the checkerboard synergy test, a range of concentrations was prepared for colistin and AgNPs. 100 µL of each was added to wells containing 100 µL of 1 × 107 CFU/mL of isolates and incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. All tests, including the negative control, were performed in triplicate51,52. The MBIC of each isolate, at which 90% of the produced biofilm was inhibited, was determined as follows52:

To evaluate the synergistic effect of AgNPs@CL on biofilm inhibition, a range of colistin and AgNPs concentrations based on the MBIC values were prepared. 50 µL of each was mixed and introduced to each well containing 100 µL of 1 × 107 CFU/mL inoculum and incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. The arrangement of rows and columns representing each concentration was planned the same as mentioned in the section “Growth inhibition by Checkerboard synergy test”51,52. All tests, including the negative control, were performed in triplicate. The FBIC and the FBIC index (FBICi) for each isolate were calculated using formulas mentioned in section “Growth inhibition by Checkerboard synergy test”.

Scanning electron microscopy

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, clinical isolates No. #30, and No. #354 were selected as representatives for qualitative analysis of biofilm inhibition using SEM under AgNPs, colistin, and AgNPs@CL treatments at a magnification of 5000×. For a more detailed inspection of the damage caused to the cells by AgNPs@CL treatment of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, an image with a magnification of 20,000× was also scheduled. The samples were prepared for SEM according to the protocol described by Zhong et al.53 with a few modifications. Briefly, 96-well microtitre plates were filled with 100 µL of AgNPs and CL at sub-MBIC concentrations, and AgNPs@CL at sub-FBIC concentrations for clinical isolates Nos. #30, #354, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853. Then, 100 µL of bacterial suspension at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU/mL was added to the wells. The microplates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing with normal saline solution three times. The formed biofilm was then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Merck, Germany) for 2 h, followed by a normal saline wash. An ethanol bath with serially diluted concentrations of 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% for 15 min was applied to dehydrate the samples. Finally, a gold layer was applied to the samples for visualization under scanning electron microscopy (Quanta-200, USA). All the steps were carried out for three untreated isolates.

QS genes expression profiling

Two clinical isolates, P. aeruginosa No. #354 and No. #30, were selected for RT-qPCR analysis based on their distinct responses to AgNPs@CL treatment in the checkerboard synergy assay and their phylogenetic profiles. Isolate No. #354 exhibited a synergistic response, while No. #30 showed an additive effect (see section “Biofilm inhibition concentrations”). Additionally, phylogenetic analysis revealed that No. #354 belonged to a clonally related group, whereas No. #30 was genetically distinct (see section “Phylogenetic profile”). Both isolates also demonstrated the highest colistin MIC values (128 µg/mL), highlighting their clinical relevance (see section “MIC values”). P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 was included as a control strain for comparison in all gene expression analyses.

Six essential QS genes involved in biofilm regulation, including lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pelA, and pslA, were chosen as targets for AgNPs, CL, and AgNPs@CL treatment. Two 16sRNA and rpoD internal controls were used to normalize the target genes. Total RNA was extracted using an RNAxPlus kit (SinaClon, Iran) at sub-MBIC concentrations of each isolate when treated with AgNPs or CL alone and sub-FBIC concentrations when treated with AgNPs@CL. This was followed by cDNA synthesis using M-MLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Parstous Co., Iran). Standard and melt curve analyses were performed to establish the amplification efficiency and specificity of the primers, respectively. The Applied Biosystems 7500 StepOne Plus System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) was used to amplify the targets using the primer sequences provided in Table 2. ExcelTaqTM Taq DNA polymerase (Smobio, Taiwan Maste Mix) with SYBR Green dye was used for amplification. The following were the cycling conditions: incubation for 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 55 °C, and 20 s at 72°C54. Every experiment included a negative control with no cDNA to screen for contamination. All tests were performed in duplicate. Relative quantification of expression profiles was calculated based on the 2−ΔΔCT method55. We plotted a heatmap based on the Log2 fold-changes of the treatments in RT-qPCR using Clustvis, a web tool for visualizing the clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap56. Tukey–Kramer all pairwise comparison tests for parametric analysis were performed by the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) to determine significant differences among treatments. The P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The studied isolates

Ten clinical isolates (Nos. #354, #800, #355, #313, #380, #321, #74, #261, #3R, and #30) were selected for the study. All isolates were successfully cultured on blood agar, MacConkey agar, and cetrimide agar. Colonies on blood agar exhibited a metallic sheen and beta-hemolysis, while those on cetrimide agar showed the characteristic green pigmentation of P. aeruginosa. On MacConkey agar, all isolates were non-lactose fermenters with pale colonies. The distinct grape-like smell of P. aeruginosa was detected. Confirmation of P. aeruginosa identification was achieved through a series of biochemical tests. All isolates exhibited positive results for the catalase and oxidase tests, with a rapid color change, and were capable of growth at 42 °C. The TSI (Triple Sugar Iron) test displayed an Alkaline/Alkaline (K/K) reaction, in line with the non-fermentative characteristics of P. aeruginosa. Urease testing yielded negative results, while citrate utilization was positive on Simmons Citrate agar. The O/F test confirmed oxidative metabolism, further supporting the identification of the isolates37,38.

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 was used as a positive control strain for biofilm formation. To conduct SEM and RT-qPCR analysis, P. aeruginosa isolate No. #354 was chosen as a representative of five clonally identical isolates highlighted in yellow on the dendrogram due to its synergistic behavior against AgNPs@CL. P. aeruginosa isolate No. #30 was selected as it exhibited additive behavior against AgNPs@CL and had no phylogenetic relatedness with the other isolates, highlighted in pink (section “Phylogenetic profile”). Both isolates showed the highest MIC values against colistin (128 µg/mL) (section “MIC values”).

Phylogenetic profile

Among the 10 clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, five isolates (Nos. #354, #800, #355, #313, and #380) clustered together with a high degree of similarity (70%), while the remaining (Nos. #321, #74, #261, #3R, and #30) showed only 27% similarity (Fig. 1A). In the MSTree (Fig. 1B), all five closely related isolates were grouped together in an orange partition.

(A) Five isolates highlighted in yellow box are clonally close. The pink highlighted box encloses five clinical isolates along with P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, which are genetically distant. Three isolates enclosed in boxes were chosen for SEM and RT-PCR analysis. (B) Minimum Spanning Tree illustrates isolates’ distribution based on their distance in loci. Five green circles partitioned in pink with thick connecting lines are distinct in only two loci. Each circle belongs to an isolate. Dotted lines between circles demonstrate distances in more than two loci among the isolates. All concentrations are in µg/mL.

AgNPs characterization

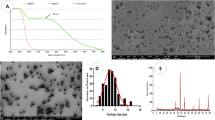

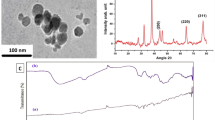

The electron microscope photographs revealed that nanoparticles are polymorphic in shape and have an average 60–80 nm diameter, as shown in Fig. 2A, B, respectively. The XRD analysis shows that the prominent peaks observed at 2θ in the regions of 38.39, 44.69, 64.79, and 77.79 corresponded to the Miller indices (111), (200), (220), and (311), respectively (Figs. 2C). The FTIR spectrum of the synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) showed several distinct peaks, suggesting the presence of specific functional groups on the nanoparticle surface. The peak at 3419.84 cm−1 also indicates O–H stretching, providing additional evidence for the existence of hydroxyl groups. The peak at 1646.73 cm−1 is likely due to C=C stretching, a characteristic feature of carboxyl groups (–C=O), and carbonyl group (–C=O) stretching vibration of proteins. The peak at 1384 cm−1 is associated with C–H bending of COO– or carboxylate groups57. The FTIR spectrum is illustrated in Fig. 2D. The maximum absorbance (λ max) and the surface charge of AgNPs were recorded as 500–550 nm and − 22.3 mV, respectively (Fig. 3A, B, respectively).

AgNPs characterization. (A) TEM photograph at 100 nm displays polymorphic AgNPs. (B) Histogram displaying the size distribution of nanoparticles analyzed through ImageJ software based on their diameter. The majority of the nanoparticles had a diameter of 60–80 nm. (C) XRD pattern of the peaks observed at 2θ at 38.39, 44.69, 64.79, and 77.79 corresponded to Miller indices (111), (200), (220), and (311). (D) The FTIR spectrum of AgNPs displays intense absorption bands.

(A) The maximum absorbance (λ max) of AgNPs were recorded as 500–550 nm in UV-Vis spectrophotometer. (B) The surface charge of AgNPs was measured to be-22.3 Mv. (C) Cell viability value of AgNPs. When L929 cells exposed to 37.5 and 75 µg/mL of AgNPs, the percentage of cells that remained alive were 55.63 and 50.22, respectively. The symbol * indicates a statistically significant difference between the 37.5 µg/mL and control negative groups (P-values < 0.05). (D) MTT cytotoxicity of AgNPs at 37.5 µg/mL and 75 µg/mL.

AgNPs cytotoxicity

At a concentration of 37.5 µg/mL of AgNPs, the viability of murine L929 fibroblast cells was observed to exceed 50%. The result was statistically significant, with a P-value of 0.0001 (significance level set at P-value < 0.05). The 95% confidence interval for the effect size was between − 50.49 and − 34.95. Additionally, the R-squared value was 0.9831, indicating that 98.31% of the variance in cell viability was explained by the model. At a concentration of 75 µg/mL of AgNPs, 50% of the murine L929 fibroblast cells remained viable, which corresponds to the calculated IC50 value (Fig. 3C). In Fig. 3D, untreated cells are displayed along with cells treated with 37.5 µg/mL and 75 µg/mL of AgNPs.

Antibiotic susceptibility profile

In the disk diffusion test, all clinical isolates and control strains were categorized as MDR as they were resistant to at least one antibiotic from the following categories: Aminoglycosides (Gentamicin, Amikacin), Antipseudomonal carbapenems (Imipenem, Meropenem), Antipseudomonal cephalosporins (Ceftazidime, Cefepime), Antipseudomonal fluoroquinolones (Ciprofloxacin), Antipseudomonal penicillins + β-lactamase inhibitors (Piperacillin-tazobactam), Monobactams (Aztreonam), and Polymyxins (Colistin, section “MIC values”). Figure 4A displays the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of isolate No. #354 using the disk diffusion method as an example.

MIC values

The minimum and maximum MIC values for CL were 8 µg/mL (P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and No. #261) and 128 µg/mL (Nos. #354, #355, #380, and #30), respectively. The minimum and maximum MIC values for AgNPs were 0.07 µg/mL (No. #3R) and 37.5 µg/mL (Nos. #354, #313, and #380), respectively. A detailed overview of each isolate’s MIC values for AgNPs and CL is shown in Fig. 1A.

Checkerboard synergy patterns

According to the checkerboard results, AgNPs@CL showed synergistic effects on the growth inhibition of isolates Nos. #354, #800, #355, #313, #380, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853. The concentration of AgNPs and CL was reduced by a maximum of 4-fold (No. #380) and 3-fold (No. #355), respectively. The lowest FICi was 0.31 for isolate No. #380, indicating a strong synergistic effect. AgNPs@CL treatment showed an additive effect on the remaining isolates, with a FICi of 1 for all additive isolates. Figure 1A displays the values of FIC and FICi for each isolate.

Assessment of biofilm formation ability

All P. aeruginosa isolates (100%) were categorized as strong biofilm formers. The OD values for isolates Nos. #354, #30, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 were 3.346, 3.265, and 1.901, respectively. The mean OD of control negative wells was documented as 0.099. Figure 4B shows the microtitre plate assay used to assess the biofilm production capacity of the isolates.

Biofilm inhibition concentrations

Checkerboard findings showed that AgNPs@CL exhibited synergistic effects on isolates Nos. #354, #800, #355, #313, #380, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 in preventing the development of biofilms. In isolate No. #354, which had the lowest FBICi of 0.25, the concentration of both AgNPs and CL was reduced by up to three times. The AgNPs@CL treatment had an additive effect on the remaining isolates, showing a FBICi of 1 for all the additive isolates. Figure 1A displays the values of FBIC and FBICi for each isolate.

Scanning electron microscopy graphs

At 5000× magnification, SEM images revealed significant biofilm formation in untreated P. aeruginosa strains ATCC 27,853, No. #30, and No. #354, displaying thick structures. In contrast, samples treated with either AgNPs or CL alone showed a significant decrease in biofilm mass. The biofilms appeared less compact and more spread out, indicating that both treatments were successful in preventing biofilm formation to some extent. The combination of AgNPs@CL resulted in a more noticeable inhibition of biofilm formation. SEM images revealed a substantial decrease in biofilm mass for all three isolates, showing disrupted and sparse biofilms. This suggests that the combined treatment is more effective in preventing biofilm formation than either treatment individually (Fig. 5A). At 20,000× magnification, distinct morphological changes were observed in bacterial cells treated with AgNPs@CL compared to the untreated control. The most significant damages included: (I) Pierced Membranes (yellow dashed circle): The SEM images clearly demonstrate instances of membrane perforation in the treated cells, suggesting that the AgNPs@CL significantly disrupt cell envelope integrity58. (II) Cell Shrinkage (red dashed circle): Cells treated with AgNPs@CL showed shrinkage, suggesting osmotic imbalance and loss of cellular turgor, common signs of cellular stress or damage59. (III) Cell Leakage (white dotted circle): Intracellular content leakage was observed in the treated samples, indicating bacterial membrane compromise and the efflux of cellular material58. (IV) Membrane Blebs (green dashed circle): The presence of membrane blebs suggests that the cells may be undergoing stress or damage, potentially leading to cell death60 (Fig. 5B.1,B.2).

(A) Isolates under AgNPs, Colistin (CL), and AgNPs@CL treatment. The first left column depicts Un-Treated samples. Biofilm mass mitigation during single and combined treatments is evident in all three isolates (5000× magnification). (B.1) Biofilm cement surrounds the sessile cells in the developing Un-Treated biofilm. (B.2) Biofilm treated at sub-FBIC concentration of AgNPs@CL suggest extreme cellular damages. Pierced membrane (yellow dashed circle), cell shrinkage (red dashed circle), cell leakage (white dotted circle), and membrane blebs (green dashed circle) together with obvious biofilm mass mitigation in a scanty microscopic field (20,000× magnification). The lines observed in the SEM images are likely due to the deformation of the polystyrene substrate under pressure or chemical interactions during biofilm preparation. These artifacts do not affect the integrity of the biofilm itself or the interpretation of the treatment effects observed.

QS genes expression profile

The expression of target genes in isolates No. #354 and No. #30, as well as P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, was significantly reduced (P-values < 0.05) after treatment with AgNPs, CL, and AgNPs@CL compared to the control group. Treatment with AgNPs@CL led to a significant decrease in the expression of all examined genes in clinical isolate No. #354 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 when compared to treatment with AgNPs or CL individually. In isolate No. #354, the pelA gene exhibited the most notable suppression in the AgNPs@CL treatment (− 5.83 log2-FC) compared to either AgNPs (− 3.56 log2-FC) or CL (− 3.56 log2-FC) alone. In P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, the pelA gene also exhibited the most notable suppression in the AgNPs@CL treatment (− 5.63 log2-FC) compared to either AgNPs (− 3.69 log2-FC) or CL (− 2.62 log2-FC) alone. In isolate No. #30, there was no statistically significant suppression of genes in the AgNPs@CL treatment compared to AgNPs or CL alone (Fig. 6).

The heatmap clustering illustrates the log2-fold changes of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, isolates Nos. #354, and #30 normalized to two reference genes under the scheduled treatments. The numbers in parentheses indicate the level of suppression in percentage. Both rows and columns are clustered using Euclidean distance and Ward linkage. The suppression range varies from purple (little) to red (marked). Dendrogram A classifies isolates into three clusters based on the suppression level confronting scheduled treatments.

The cluster analysis of the heatmap produced dendrogram A, grouping the scheduled treatments into clusters 1, 2, and 3. Cluster A-1 comprises isolate No. #354 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 when treated with AgNPs@CL. Cluster A-2 includes isolate No. #30 after exposure to AgNPs, CL, and AgNPs@CL. Cluster A-3 consists of isolate No. #354 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 when exposed to either AgNPs or CL individually (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The increased permeability of the bacterial outer membrane by AgNPs likely enhances the uptake of colistin, resulting in a synergistic effect in isolates Nos. #354, #380, and ATCC 27,853. Colistin exerts its bactericidal effect primarily by binding to LPS in the outer membrane, displacing divalent cations that stabilize LPS packing, and increasing membrane permeability61. Recent evidence also indicates that colistin targets LPS in the cytoplasmic membrane, where it disrupts cation bridges and compromises membrane integrity62. Based on the findings from Dupuy et al.63, colistin’s interaction with bacterial membranes is more nuanced than previously understood. The study demonstrates that colistin binds with high affinity to the LPS layer of Gram-negative bacteria’s outer membrane, primarily localizing in the headgroup region without deeply penetrating the membrane. While our study supports these mechanisms conceptually, we did not directly assess LPS integrity or disruption. Due to their small size, AgNPs can penetrate damaged membranes, enhancing their antibacterial effects by disrupting the biofilm matrix and inhibiting QS gene expression. Isolate No. #30 exhibited an additive effect, where the combination of AgNPs and colistin resulted in a slight reduction in MIC and MBIC. However, this reduction was not as significant as in the synergistic cases. The differences in susceptibility could be attributed to the genetic diversity among P. aeruginosa isolates. Isolate No. #30 may possess genetic factors that confer a higher resistance level to AgNPs or colistin, such as efflux pumps, different biofilm matrix composition, or a different QS regulation mechanism which are less susceptible to disruption by these agents.

The results of the RT-qPCR analysis show that the combination of AgNPs@CL effectively reduced the expression of the studied QS genes in the synergistic isolates, with pelA and lasI being the most significantly suppressed. This decrease in QS gene expression led to reduced biofilm formation and increased antibacterial activity. Notably, isolate No. #30 did not show significant suppression of QS genes, which aligns with its additive response to the AgNPs@CL treatment.

Despite the observed variability in response among different isolates, our results are consistent with previous studies indicating that the combination of metal nanoparticles with antibiotics can enhance antimicrobial and anti-QS effects. Study by Radzig et al.64 support our findings, suggesting that AgNPs can potentiate the effects of antibiotics by facilitating their uptake and disrupting key bacterial functions, including QS signaling and biofilm formation.

In line with our results, Al Momani et al.65 found that biosynthesized AgNPs at 7.5 µg/ml significantly reduced the expression of lasR, lasI, and lasB genes in all tested strains compared to the control group. The reduction in gene expression ranged from 25.7 to 63.3% for lasR, 13.2–51.4% for lasB, and 15.7–69.4% for lasI. Additionally, at the same concentration, rhIR and rhII gene expression also decreased significantly, with reductions ranging from 19.7 to 43.8% and 16–40.3%, respectively. On the other hand, Saeki et al.66 observed that after 24 h of treatment with 31.25 µM bio-AgNPs, the expression of key genes in P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA14 increased significantly. In PAO1, the genes lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, pqsA, and mvfR showed 100%, 10%, 110%, 40%, 110%, and 110% increases, respectively. In PA14, the expression of lasI, lasR, rhlR, pqsA, and mvfR increased by 230%, 40%, 70%, 230%, and 250%, respectively (p < 0.05). Notably, rhlI expression was downregulated by − 40% in treated bacteria (p < 0.05). These contrasting outcomes may be attributed to differences in nanoparticle synthesis methods, concentrations used, bacterial strains tested, and experimental conditions.

The SEM analysis provided qualitative evidence of the effectiveness of the AgNPs@CL combination in disrupting biofilms. The images showed significant biofilm reduction and morphological changes in bacterial cells, such as pierced membranes and cell shrinkage, further validating the combined treatment’s impact on biofilm integrity. These findings were consistent across all tested isolates, including the genetically divergent isolate No. #30, though the extent of damage varied.

Contrary to well-established antibiotic susceptibility testing, the primary contributing factor to the dilemmas outlined above in biofilm investigations is a lack of reliable methodologies67. The scenario with AgNPs is indeed quite different, where the lack of standardized sensitivity thresholds, various synthesis methods, and the impact of shape and size on efficacy lead to inconsistent findings globally. Nevertheless, some scientists classify MIC values of ≥ 512 µg/mL against AgNO3 as silver resistant27,68,69.

The findings of this study have significant clinical implications, particularly in ICU settings where P. aeruginosa infections are common and life-threatening. The synergistic combination of green-synthesized AgNPs and colistin offers a promising strategy to combat biofilm-associated infections and MDR strains. This combination therapy could serve as an adjunct to conventional antibiotic treatments, potentially improving patient outcomes and reducing treatment failure in critically ill patients. Importantly, the observed reduction in QS gene expression highlights its role as a potential therapeutic target for biofilm control in clinical environments.

While the findings of this study are promising, there are some limitations that must be addressed. The small sample size of 10 clinical isolates may not fully represent the genetic and phenotypic diversity of P. aeruginosa strains. Additionally, the exclusion of PQS system genes, which play a complementary role in QS regulation, limits our understanding of the full impact of AgNPs@CL therapy. These limitations highlight the need for further investigations with larger sample sizes and a more comprehensive analysis of QS pathways7. Moreover, our study did not include screening the sil genes conferring silver resistance to bacteria27,67.

Future studies should focus on expanding the sample size to include clonally diverse isolates to validate the efficacy of AgNPs@CL combination therapy. Additionally, exploring the role of PQS system genes and their interactions with Las and Rhl pathways could provide a more comprehensive understanding of QS regulation. Incorporating curcumin into the AgNPs@CL combination also warrants investigation, as it may enhance the biofilm inhibition capabilities and overcome resistance in challenging isolates such as strain No. #3054.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the combination of green-synthesized AgNPs and colistin demonstrated significant synergistic effects in reducing biofilm formation and suppressing key QS genes in MDR P. aeruginosa isolates. This combination therapy effectively disrupted biofilm integrity, as evidenced by SEM analysis, and targeted essential components of QS pathways, particularly in synergistic isolates. Despite variability among clinical isolates, the results highlight AgNPs@CL as a promising adjunct therapy for biofilm-associated infections in critically ill patients. Further research is needed to optimize its clinical applicability and explore additional synergistic combinations.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- CRPA:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- CLSI:

-

Clinical laboratory Standards Institute

- QS:

-

Quorum sensing

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- ATCC:

-

American Type Culture Collection

- LB:

-

Luria-Bertani

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- FTIR:

-

Fourier transform infrared

- AgNPs:

-

Silver nanoparticles

- CL:

-

Colistin

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentrations

- MBIC:

-

Minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration

- FIC:

-

Fractional inhibitory concentration

- FICi:

-

Fractional inhibitory concentration index

- ∑ FICi:

-

FICiAgNPs+FICiCL

- FBIC:

-

Fractional biofilm inhibitory concentration

- MLVA:

-

Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis

- MSTree:

-

Minimum spanning tree

- mcr:

-

mobilized colistin resistance

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium

- UPGMA:

-

Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

References

Jeschke, M. G. et al. Burn injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0145-5 (2020).

WHO. Burns. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (2018).

Santucci, S., Gobara, S., Santos, C., Fontana, C. & Levin, A. Infections in a burn intensive care unit: Experience of seven years. J. Hosp. Infect. 53, 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1340 (2003).

Church, D., Elsayed, S., Reid, O., Winston, B. & Lindsay, R. Burn wound infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19, 403–434. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006 (2006).

Ciofu, O. & Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents—how P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 10, 913. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00913 (2019).

Papenfort, K. & Bassler, B. L. Quorum sensing signal–response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 576–588 https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.89 (2016).

Lee, J. & Zhang, L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 6, 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-014-0100-x (2015).

Moradali, M. F., Ghods, S. & Rehm, B. H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lifestyle: A paradigm for adaptation, survival, and persistence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 39. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00039 (2017).

Diggle, S. P. et al. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa quinolone signal molecule overcomes the cell density-dependency of the quorum sensing hierarchy, regulates rhl‐dependent genes at the onset of stationary phase and can be produced in the absence of LasR. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03672.x (2003).

Colvin, K. M. et al. The Pel polysaccharide can serve a structural and protective role in the biofilm matrix of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1001264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001264 (2011).

Li, X. Z. & Nikaido, H. Efflux-mediated drug resistance in bacteria: An update. Drugs 69, 1555–1623. https://doi.org/10.2165/11317030-000000000-00000 (2009).

Hooper, D. C. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 337. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0702.010239 (2001).

H⊘ iby, N., Ciofu, O. & Bjarnsholt, T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in cystic fibrosis. Future Microbiol. 5, 1663–1674. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.10.125 (2010).

Queenan, A. M. & Bush, K. Carbapenemases: The versatile β-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 440–458. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00001-07 (2007).

Dai, T., Huang, Y. Y. & Hamblin, M. R. Photodynamic therapy for localized infections—State of the Art. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 6, 170–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.10.008 (2009).

Tamma, P. D., Cosgrove, S. E. & Maragakis, L. L. Combination therapy for treatment of infections with gram-negative bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25, 450–470. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.05041-11 (2012).

Ashburn, T. T. & Thor, K. B. Drug repositioning: Identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1468 (2004).

Mah, T. F. C. & O’Toole, G. A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9, 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01913-2 (2001).

Aslan, A. T. & Akova, M. The role of colistin in the era of new β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Antibiotics 11, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11020277 (2022).

El-Sayed Ahmed, M. A. E. G. et al. Colistin and its role in the era of antibiotic resistance: An extended review (2000–2019). Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 868–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1754133 (2020).

Falagas, M. E., Kasiakou, S. K. & Saravolatz, L. D. Colistin: The revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1086/429323 (2005).

Nation, R. L., Velkov, T. & Li, J. Colistin and polymyxin B: Peas in a pod, or chalk and cheese? Clin. Infect. Dis. 59, 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu213 (2014).

Deris, Z. Z. et al. The combination of colistin and doripenem is synergistic against Klebsiella pneumoniae at multiple inocula and suppresses colistin resistance in an in vitro Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5103–5112. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01064-12 (2012).

Poirel, L., Jayol, A. & Nordmann, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 557–596. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00064-16 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Re-sensitization of Mcr carrying multidrug resistant bacteria to colistin by silver. PNAS 119, e2119417119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119417119 (2022).

Muenraya, P., Sawatdee, S., Srichana, T. & Atipairin, A. Silver nanoparticles conjugated with colistin enhanced the antimicrobial activity against gram-negative bacteria. Molecules 27, 5780. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185780 (2022).

AEDMS, H., Rasmy, S., Abdoul-Magd, D., Kashef, M. & El-Bazza, Z. The increasing threat of silver-resistance in clinical isolates from wounds and burns. Infect. Drug Resist. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S209881 (2019).

Gurunathan, S. et al. Biosynthesis, purification and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Escherichia coli. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 74, 328–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.07.048 (2009).

Ahmed, S., Ahmad, M., Swami, B. L. & Ikram, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica aqueous leaf extract. j. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 9, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrras.2015.06.006 (2016).

Selvaraju, G. D. et al. Fabrication and characterization of surgical sutures with propolis silver nano particles and analysis of its antimicrobial properties. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 34, 102082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102082 (2022).

Martorano-Fernandes, L., Cavalcanti, Y. & Almeida, L. Inhibitory effect of Brazilian red propolis on Candida biofilms developed on titanium surfaces. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 20, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-02893-9 (2020).

Fernández-Calderón, M. C. et al. Antifungal and anti-biofilm activity of a new Spanish extract of propolis against Candida glabrata. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 21, 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03323-0 (2021).

Przybyłek, I. & Karpiński, T. M. Antibacterial properties of propolis. Molecules 24, 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24112047 (2019).

Koru, O. et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of propolis samples from different geographical origins against certain oral pathogens. Anaerobe 13, 140–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2007.02.001 (2007).

Grecka, K. et al. Effect of ethanol extracts of propolis (EEPs) against Staphylococcal biofilm—microscopic studies. Pathogens 9, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080646 (2020).

Almuhayawi, M. S. Propolis as a novel antibacterial agent. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 3079–3086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.09.016 (2020).

Tille, P. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology-E-Book (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015).

Procop, G. W., Church, D. L., Hall, G. S. & Janda, W. M. Koneman’s Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2020).

Vu-Thien, H. et al. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis for longitudinal survey of sources of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 3175–3183. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.00702-07 (2007).

Habibipour, R., Moradi-Haghgou, L. & Farmany, A. Green synthesis of AgNPs@ PPE and its Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation activity compared to pomegranate Peel extract. Int. J. Nanomed., 6891–6899 (2019).

Silici, S. & Kutluca, S. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of propolis collected by three different races of honeybees in the same region. J. Ethnopharmacol. 99, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.046 (2005).

Beer, C., Foldbjerg, R., Hayashi, Y., Sutherland, D. S. & Autrup, H. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles—nanoparticle or silver ion? Toxicol. Lett. 208, 286 –292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.11.002 (2012).

Bilal, M. et al. Development of silver nanoparticles loaded chitosan-alginate constructs with biomedical potentialities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 105, 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.047 (2017).

Barbosa, A. C. M. S. et al. Nematicidal activity of silver nanoparticles from the fungus Duddingtonia flagrans. Int. J. Nanomed., 2341–2348. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S193679 (2019).

Hudzicki, J. Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion susceptibility test protocol. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 15, 1–23 (2009).

Wayne, P. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI Supplement M100 (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2024).

Balouiri, M., Sadiki, M. & Ibnsouda, S. K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 6 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2015.11.005 (2016). 71 – 9.

Odds, F. C. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52, 1. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkg301 (2003).

Bonapace, C. R., Bosso, J. A., Friedrich, L. V. & White, R. L. Comparison of methods of interpretation of checkerboard synergy testing. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 44, 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0732-8893(02)00473-X (2002).

Stepanović, S. et al. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: Overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by Staphylococci. APMIS 115, 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_630.x (2007).

Cady, N. C. et al. Inhibition of biofilm formation, quorum sensing and infection in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by natural products-inspired organosulfur compounds. PLoS One. 7, e38492. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038492 (2012).

Sandala, J. & Gunn, J. S. In vitro evaluation of anti-biofilm agents against Salmonella enterica. In Salmonella: Methods and Protocols, 127–139 (2021).

Zhong, H. et al. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of Temporin-GHc and Temporin-GHd against cariogenic bacteria, Streptococcus mutans, front microbiol. 10 2854, (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02854

Azimzadeh, M. et al. Synergistic effects of nano Curcumin mediated photodynamic inactivation and nano-silver@ colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Photodiagn. Photodyn Ther. 45, 103971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2024.103971 (2024).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408. https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Metsalu, T. & Vilo, J. ClustVis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap, Nucleic Acids Res. 43 W566–W70, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv468. (2015).

Singh, P. & Mijakovic, I. Strong antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles obtained by the green synthesis in Viridibacillus sp. extracts, front microbiol. 13, 820048. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.820048 (2022).

Burdușel, A. C. et al. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: An up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials 8, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8090681 (2018).

Zhang, X. F., Shen, W. & Gurunathan, S. Silver nanoparticle-mediated cellular responses in various cell lines: An in vitro model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17101603 (2016).

Ragonese, F. et al. Silver ions promote blebs growth in U251 glioblastoma cell by activating nonselective cationic currents. Sci. Rep. 9, 12898. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49198-7 (2019).

Roberts, J. L. et al. In vitro evaluation of the interaction of dextrin–colistin conjugates with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Med. Chem. 59, 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01521 (2016).

Sabnis, A. et al. Colistin kills bacteria by targeting lipopolysaccharide in the cytoplasmic membrane. Elife 10, e65836. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65836 (2021).

Dupuy, F. G. et al. Selective interaction of colistin with lipid model membranes. Biophys. J. 114, 919–928 (2018).

Radzig, M. et al. Antibacterial effects of silver nanoparticles on gram-negative bacteria: Influence on the growth and biofilms formation, mechanisms of action. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 102, 300–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.07.039 (2013).

Al-Momani, H. et al. The efficacy of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Sci. Rep. 13, 8876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35919-6 (2023).

Saeki, E. K. et al. Effect of biogenic silver nanoparticles on the quorum-sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14. Microorganisms 10, 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10091755 (2022).

Thieme, L. et al. MBEC versus MBIC: The lack of differentiation between biofilm reducing and inhibitory effects as a current problem in biofilm methodology. Biol. Proced. Online 21, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12575-019-0106-0 (2019).

Safain, K. S. et al. Prevalence of silver resistance determinants and extended-spectrum β-lactamases in bacterial species causing wound infection: First report from Bangladesh. New. Microbes New. Infect. 52, 101104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2023.101104 (2023).

Sütterlin, S., Dahlö, M., Tellgren-Roth, C., Schaal, W. & Melhus, Å. High frequency of silver resistance genes in invasive isolates of Enterobacter and Klebsiella species. J. Hosp. Infect. 96, 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.04.017 (2017).

Krishnamoorthy, S., Shah, B. P., Lee, H. H. & Martinez, L. R. Microbicides alter the expression and function of RND-type efflux pump AdeABC in biofilm-associated cells of Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01045-15 (2016).

Yang, Y. et al. Inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms by 405-nanometer-light-emitting diode illumination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e00092–e00020. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00092-20 (2020).

Yang, Y. X. et al. A new quorum-sensing inhibitor attenuates virulence and decreases antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Microbiol. 50, 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-012-2149-7 (2012).

Wang, E. W. et al. Otopathogenic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains as competent biofilm formers. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 131, 983–989. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.131.11.983 (2005).

Zhou, J. W. et al. Hordenine: A novel quorum sensing inhibitor and antibiofilm agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 1620–1628. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05035 (2018).

Otani, S. et al. J.-i. Kadota, Sub-minimum inhibitory concentrations of Ceftazidime inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. J. Infect. Chemother. 24, 428–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2018.01.007 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Vice-chancellor of Research of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran, for advocating this research. This article is extracted from the thesis of a doctoral student (Ph.D.) in medical bacteriology.

Funding

This study was funded by the Vice-chancellor of Research and Technology of Hamadan University of medical sciences, Hamadan, IRAN, under Grant number: 140004293640.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y.A. and A.B. designed and supervised the study. M.Y.A., G.G. and M.A. performed data interpretation. M.A., A.N., A.T., A.F. and M.P. were responsible for data collection and doing experiments.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethic comity of the Hamadan University of Medical sciences, Hamadan, Iran (Ethic approval codes: IR.UMSHA.REC.1400.255). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical Review Board approved informed consent taken from all the participants and their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azimzadeh, M., Greco, G., Farmani, A. et al. Biofilm inhibition of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa using green-synthesized silver nanoparticles and colistin. Sci Rep 15, 14993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00005-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00005-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Biofilm-dispersal patterns in ESKAPE pathogens

Archives of Microbiology (2025)