Abstract

To evaluate the acute effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), static (SS) and dynamic (DS) stretching on flexibility, power, and balance in contemporary dancers and to analyze the time-dependent flexibility changes to optimize stretching strategies for training and performance. A randomized crossover trial was conducted with 24 university-level contemporary dancers. In phase one, participants completed sit-and-reach (S&R), countermovement jump (CMJ), and Y-balance (YBT) tests immediately post-stretching. In phase two, only S&R was measured before stretching, immediately after, and at 5, 10, and 15 min post-stretching. PNF (ES = 0.329, p < .001), SS (ES = 0.263, p < .01), and DS (ES = 0.306, p < .01) significantly improved S&R, with PNF and DS being more effective than control (CON) (p < .05). DS and PNF showed progressive improvements over 15 min (p < .01), while SS peaked at 10 min (ES = 0.389, p < .01) before slightly declining (ES = 0.343, p < .01). No significant changes were found in CMJ or YBT (p > .05). For contemporary dancers who require high flexibility, SS, DS, and PNF stretching effectively enhance flexibility within 15 min post-stretching without negatively impacting power or balance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary dance is a performing art that integrates athletic movement with artistic expression1. In pursuit of aesthetic excellence, dancers often push the limits of human anatomy to achieve extreme ranges of motion (ROM)2. In addition to superior flexibility, dancers require high neuromuscular power output and exceptional balance to execute rapid, high-intensity movements2. Therefore, optimizing the interplay between muscular strength, flexibility, and balance is crucial for maximizing artistic expression and technical precision.

Stretching has long been recommended as a fundamental component of warm-up routines to optimize athletic performance3. Among various stretching techniques, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) and static stretching (SS) have been well-documented as effective methods for increasing ROM4, primarily by reducing muscle-tendon unit (MTU) stiffness and enhancing stretch tolerance4,5. However, some studies have reported that SS and PNF stretching may acutely impair athletic performance by reducing maximal voluntary force, muscle power, or contractile properties6,7,8. These adverse effects are thought to arise from multiple neural and peripheral mechanisms, mainly decreases in muscle-tendon stiffness9. Nevertheless, other research suggests that when SS is incorporated into a comprehensive warm-up—including aerobic activity, subsequent dynamic stretching (DS), and additional dynamic movements, when static stretches are limited to ≤ 60 s per muscle group, its adverse effects on performance are generally negligible10. Despite this, concerns over potential performance impairments have led to a reevaluation of SS in athletic warm-ups, with some studies even recommending its exclusion. In contrast, DS has emerged as a preferred alternative, as it enhances ROM without impairing subsequent performance and may even improve it. Consequently, DS is now often recommended over SS in pre-competition warm-ups3.

However, existing studies on the acute effects of DS on athletic performance have yielded inconsistent results, with reports of performance enhancement11,12, no significant changes10,13, and even performance decrements14,15. These discrepancies stem from the targeted muscle groups, stretching duration, intensity, contraction type, and movement speed16. Notably, previous findings from general athletic populations may not fully apply to dancers exhibiting inherently high flexibility levels. The impact of stretching on their muscle performance may differ from that observed in other populations17,18. Furthermore, most studies have primarily focused on the immediate effects of stretching, with limited research investigating the time-dependent nature of flexibility gains post-stretching. Therefore, the present study aimed to systematically assess the acute effects of SS, DS, and PNF stretching on contemporary dancers’ athletic performance and to examine the time course of ROM enhancements following stretching. By identifying optimal time windows for implementing stretching strategies, this study seeks to provide practical recommendations for selecting appropriate stretching modalities and timing in real-world applications, ultimately optimizing dancers’ movement efficiency and performance.

Methods

Experimental approach to the problem

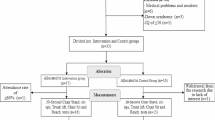

This study employed a randomized crossover-controlled trial design spanning 16 weeks. The experiment comprised two phases: a 2-week familiarization period and a 4-week formal experiment. To eliminate potential carryover effects from the previous phase, a 4-week washout period was implemented between the two phases (Fig. 1). During the formal experiment, participants underwent four weeks of stretching training, with one session conducted weekly. In each session, they were randomly assigned to one of four groups: PNF, DS, SS, or Control group (CON) (no stretching intervention). To counterbalance order effects, the sequence of stretching interventions was randomized using a Latin square design. Each stretching session lasted 20 min, consisting of a 5-minute warm-up followed by 15 min of stretching exercises. The exercises targeted major lower limb muscles, including the iliopsoas, quadriceps femoris, gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius. Each muscle group underwent three sets of stretching, with each stretch held for 30 s. Rest periods were 5 s between sets and 15 s between different exercises.

Subjects

Sample size estimation was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9 software, based on a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) power analysis. The parameters were set as follows: effect size (f = 0.5), significance level (α = 0.05), statistical power (1-β = 0.9), number of groups (4), and number of measurements per group (4). The results indicated that a minimum of 20 participants was required to achieve 90% statistical power. Considering potential dropouts, 24 university students majoring in contemporary dance voluntarily participated in the study. One participant could not complete the post-testing due to illness (Fig. 2).

Participants were included if they voluntarily participated and had at least two years of contemporary dance training experience. They had no physical impairments, sports-related injuries, cardiovascular diseases, or respiratory conditions and had no history of muscular injuries. Before the formal experiment, all participants received a detailed explanation of the study design and were instructed to obtain at least 8 h of sleep the night before testing, avoid alcohol, caffeine, and energy drinks within 24 h before testing, wear consistent or similar attire across all four experimental sessions, and refrain from intense physical activity within 24 h prior to testing. To minimize the influence of circadian rhythms, testing sessions were scheduled at consistent times, with a maximum deviation of one hour. All participants provided written informed consent. The study strictly adhered to the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee at Guangzhou Sport University. (Approval No: 2023LCLL-75) and registered at www.chictr.org.cn (Registration No: ChiCTR2400094001, registered on 16/12/2024).

Procedures

Before the formal experiment, participants completed a two-week familiarization period, during which they practiced the stretching techniques and performance tests to minimize learning effects. Baseline and pre-test assessments were conducted during this period.

Before each testing session or stretching intervention, participants completed a standardized 5-minute treadmill warm-up at a constant pace. They were then randomly assigned to perform one of the three stretching protocols (PNF, SS, or DS) or to the control condition with no stretching intervention. In the first phase, participants performed the S&R test, CMJ test, and YBT sequentially after stretching to assess the effects of stretching on flexibility, power, and balance. This phase aimed to validate the efficacy of the applied stretching strategies (Fig. 3). Given that the first phase demonstrated a significant improvement in S&R performance, the second phase focused on evaluating the time-dependent effects of flexibility gains. Specifically, participants performed the S&R test at baseline (pre-stretching) and 0, 5, 10, and 15 min post-stretching (Fig. 4). The experimental procedures remained identical across both phases. To ensure consistency and minimize measurement variability, all tests were conducted by a single trained investigator following standardized procedures.

Outcome measures

S and R test

Participants sat with their legs fully extended and feet flat against the testing board. While keeping the upper body leaning forward and arms extended, they slowly pushed the slider with their middle fingers as far as possible without sudden exertion or additional force after the initial push. The test was repeated twice, and the best score was recorded in centimeters (cm) to one decimal place, with a greater distance indicating better flexibility.

CMJ test

Participants stood on a vertical jump mat (SmartJump, Fusion Sport, Australia) with their hands on their hips. After a rapid downward squat, they immediately performed a maximal vertical jump while maintaining an upright posture and ensuring full hip and knee extension. Landing had to occur within the designated area on the jump mat, and the hands were required to remain on the hips throughout the jump. Jumps that did not meet these criteria were excluded. The primary outcome measure was jump height (cm), which was calculated based on flight time using the SmartJump system’s built-in algorithm. Participants completed three trials with a 15-second inter-trial rest period, and the highest recorded jump height was used for analysis.

YBT

During the familiarization session, the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the medial malleolus of the same-side foot was measured using tape. Participants performed the test barefoot, standing on the testing platform with the right foot positioned on the platform and the big toe aligned with the red starting line. With hands on their hips, participants pushed the sliding reach indicator with their left foot in three directions: anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral. Throughout the test, participants had to maintain foot stability and keep their hands in contact with the ASIS. All YBT assessments were supervised by experienced, professionally trained assessors. The composite score for the lower-limb YBT was calculated to quantify dynamic balance performance, where a higher composite score indicated superior balance ability. The score was determined using the following formula:

Stretching protocols

The stretching protocols targeted significant muscle groups, including the iliopsoas, quadriceps, gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and triceps surae. Experienced researchers supervised all stretching exercises to ensure proper execution. Each stretching exercise was performed for three sets, with a 5-second rest between sets and a 15-second rest between different stretching exercises. For the SS protocol, each stretch was held at moderate discomfort for 30 s. In the DS protocol, stretches were performed rhythmically at a pace of 20 repetitions per minute for 30 s. The PNF stretching protocol utilized the Hold-Relax with Agonist Contraction (HR-AC) technique. First, the therapist passively stretched the target muscle group to a position of mild discomfort and instructed the participant to maintain the stretch for 5 s. Next, participants performed a maximal isometric contraction against manual resistance applied by the therapist for 5 s. Upon relaxation, participants actively engaged the antagonist muscle group to further enhance the range of motion and held the extended position for 20 s.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using JASP 19.1 software. Data were presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data normality, and Levene’s test was conducted to evaluate the homogeneity of variance. Between-group differences in baseline characteristics were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

In the first phase, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects of time (pre- vs. post-stretching) and group (PNF, SS, DS, CON) on S&R, CMJ, and YBT performance. If a significant time × group interaction was observed, Bonferroni correction was applied for post hoc comparisons to evaluate between-group differences. In the second phase, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the effects of time (pre-stretching, 0, 5, 10, and 15 min post-stretching) on S&R performance within each group. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d, ES) were calculated for pre-to-post stretching changes within each group to quantify the magnitude of training effects. Effect sizes were interpreted as follows: large (ES > 0.8), moderate (0.5 ≤ ES ≤ 0.8), small (0.2 ≤ ES < 0.5), and negligible (ES < 0.2). Statistical significance was set at p ≤ .05; all analyses were two-tailed.

Results

Before the intervention

No training-related injuries were reported throughout the study. The baseline characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1.

First phase of the experiment

A significant main effect of time (F(1, 88) = 28.45, p < .01) and a significant group × time interaction effect (F(3, 88) = 3.77, p = .013) were observed for the S&R test, indicating that the stretching interventions influenced flexibility performance. Specifically, moderate improvements in S&R performance were found in the PNF (ES = 0.329, p < .01), SS (ES = 0.263, p < .01), and DS (ES = 0.306, p < .01). In contrast, no significant improvement was observed in the CON (p > .05). Between-group comparisons revealed that PNF and DS were significantly more effective than the control condition in enhancing flexibility (p < .05). However, no significant changes were observed in CMJ or YBT performance across the PNF, SS, DS, and CON (p > .05) (Fig. 5; Table 2).

Second phase of the experiment

A significant main effect of time and a significant group × time interaction effect (F(4, 352) = 29.91, p < .01) were observed for S&R performance across different time points. Specifically, moderate improvements in S&R performance were observed within 15 min post-stretching in the PNF, SS, and DS (p < .01), whereas no significant improvement was found in the CON. Throughout the testing period, both DS and PNF demonstrated a progressive increase in S&R performance (p < .01). The SS exhibited a peak improvement at 10 min (ES = 0.389, p < .01), followed by a slight decline at 15 min (ES = 0.343, p < .01); however, the improvement remained statistically significant (Fig. 6; Table 3).

Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the acute effects of SS, DS, and PNF stretching as part of a warm-up on flexibility, power, and balance in contemporary dancers. Additionally, it investigated the immediate effects of these stretching methods on the ROM and their time-dependent effects at 5, 10, and 15 min post-stretching.

In the first phase of the experiment, all three stretching methods—PNF, SS, and DS—significantly improved the ROM of contemporary dancers, consistent with previous studies4. However, no statistically significant differences were observed among the three methods of improving ROM. This finding aligns with the results of Rubini et al.19, who reported that both PNF and SS significantly increased the ROM of hip adductors in female ballet dancers without significant differences in their acute effects. Morrin et al.17 suggested SS was superior to DS in improving ROM among trained dancers. However, in the present study, despite the absence of statistically significant differences between DS and SS in ROM enhancement, DS demonstrated a trend toward greater efficacy. This phenomenon may be attributed to DS’s active and repetitive muscle contractions, which could increase muscle temperature and reduce muscle viscosity resistance, thereby enhancing tissue extensibility20. Additionally, compared to the ROM changes induced by SS, the greater angular displacement produced during DS may further facilitate ROM improvements21. The second phase of the experiment evaluated the time-dependent effects of acute stretching on flexibility gains. The ROM following SS gradually increased over 10 min, reaching its peak before slightly declining, but remained statistically significant at 15 min. This trend may be related to stress relaxation and creep effects. Continuous stretching reduces internal muscle stress, allowing it to extend to greater lengths. However, this effect gradually diminishes over time as the muscle attempts to restore its pre-stretch structure through internal remodeling22,23. In contrast, the ROM following PNF stretching continued to increase over 15 min, consistent with the findings of Ford et al.24 Since PNF stretching includes a static stretching phase, stress relaxation, and creep mechanisms may also contribute to the acute ROM gains25. Furthermore, the unique combination of the “contract-relax” and “contract-relax-antagonist-contract” techniques in PNF stretching may optimize biomechanical responses, potentially offering greater advantages in increasing ROM than SS and DS. Although earlier research hypothesized that PNF’s uniqueness mainly stems from autogenic inhibition and reciprocal inhibition mechanisms, growing evidence suggests that these neural mechanisms may not be the primary contributors to PNF-induced ROM improvements26,27,28. Instead, the acute flexibility gains from stretching are primarily associated with temporary adaptive changes in the MTU and improved stretch tolerance4,5. Studies have shown that SS significantly reduces MTU stiffness, which returns to baseline levels within 10 min, possibly explaining the ROM changes observed in this study29. However, PNF may be more effective than SS in reducing MTU stiffness30. Additionally, the contraction phase in PNF may help divert attention and reduce discomfort during stretching, thereby enhancing stretch tolerance and allowing participants to achieve higher ROM31.

The effects of DS on the mechanical properties of the MTU remain controversial. Herda et al.32 employed DS involving active muscle contractions, where the hamstrings contracted during leg movement. They found that this approach significantly increased knee joint ROM while reducing MTU stiffness and passive torque (PT), showing effects similar to SS. In contrast, Mizuno et al.33 used DS involving antagonist muscle contractions, in which tibialis anterior contractions facilitated ankle dorsiflexion. Although this approach also improved ankle joint ROM and maintained the gain after 10 min, no significant changes in MTU stiffness or muscle-tendon junction (MTJ) displacement were observed, indicating that this method primarily improved ROM by enhancing stretch tolerance rather than altering the passive mechanical properties of muscles or tendons. These conflicting results may be due to differences in DS techniques. DS involving active muscle contractions may directly influence MTU stiffness through mechanical stimulation, while DS involving antagonist contractions mainly relies on neural regulation to improve ROM. The present study adopted an active muscle contraction-based DS approach, similar to the method used by Herda et al.32 Therefore, the sustained ROM increase observed following DS in this study is primarily attributed to the reduction in MTU stiffness.

In this study, none of the stretching methods (SS, DS, or PNF) significantly affected jumping or balance performance. This result contradicts the widely accepted notion that SS and PNF stretching typically impair jumping ability34,35,36, whereas DS may be beneficial11,12. However, some studies have reported findings that are consistent with ours8,13. The reduction in strength and power observed following acute stretching is often attributed to impaired neural output and changes in MTU mechanical properties9. Behm et al.25 found that the extent of performance impairment is closely related to stretch duration, particularly when each muscle group is stretched for more than 60 s, which may negatively affect vertical jump, sprinting, maximal voluntary contraction, muscular strength endurance, balance, and reaction time. Notably, athletes who undergo long-term flexibility training may be more resistant to SS-induced power decrements. Donti et al.37 found that in adolescent gymnasts, neither a single 90-second SS nor a 3 × 30-second intermittent SS resulted in significant CMJ height reductions. A recent meta-analysis by Yu et al.38. also observed that gymnasts did not experience jumping or that strength performance declined after SS. In contrast, technical movements that rely on flexibility could be enhanced by SS, potentially due to adaptive changes in the MTU induced by long-term flexibility training. Moltubakk et al.39 further confirmed that compared to non-stretched individuals, professional ballet dancers exhibited greater compliance and ROM in the gastrocnemius tendon unit. This adaptation suggests highly flexible individuals may experience smaller torque reductions following stretching40. This indicates that athletes with long-term flexibility training may maintain muscle-tendon unit tension and energy storage capacity more effectively after acute stretching, thereby avoiding performance impairments due to stretching-induced MTU stiffness reductions.

Currently, the effects of SS on balance ability remain controversial. Behm et al.41 and Costa et al.42 applied the same stretching protocol and found that three sets of 45-second SS did not significantly impair balance ability. However, Costa et al.38 discovered that 3 sets of 15-second SS might reduce postural instability, improving balance performance. This finding was supported by Amara et al.43, who recommended short-duration SS as an effective training method for enhancing dynamic balance in adolescent female volleyball players. Therefore, the 3 × 30s stretching duration used in this study may not have reached the threshold required to induce significant neural inhibition or mechanical changes in the muscle-tendon unit, and thus did not produce a significant effect on jumping and balance performance. Moreover, most studies have reported positive effects of DS and PNF stretching on balance ability12,44,45. However, Morrin et al.17 evaluated the acute effects of DS on the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius and found no improvements in balance during a demi-pointe stance. Notably, the participants in that study were female dancers who likely possessed exceptional balance abilities due to long-term training, which may explain the lack of observed balance improvements48. Even SS lasting over 60 s may not significantly alter vertical jump37 or balance17 performance for athletes with long-term flexibility training. The structural adaptations of these dancers’ elastic components may contribute to resilience against performance impairments caused by prolonged stretching46.

Although long-term flexibility-trained athletes may not experience performance declines following SS, the choice of stretching modality may still influence power output. Melocchi et al.47 and Montalvo et al.11 found that gymnasts exhibited significant improvements in CMJ performance following DS compared to SS. This is likely because DS, due to its high similarity to movement patterns, can trigger a post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE), whereby preparatory high-intensity muscle contractions temporarily enhance muscular power output20. Additionally, DS may increase neuromuscular excitability through rapid stretching, further amplifying the PAPE7. This mechanism is closely related to the sensitivity of stretch reflexes to stretching speed, as faster stretch velocities induce greater stretch reflex potentials, leading to higher muscle activation48. Fletcher et al.49 confirmed that compared to slow stretching (50 repetitions/min), fast stretching (100 repetitions/min) significantly increased electromyographic activity and enhanced vertical jump performance more effectively. In contrast, slow stretching (50 repetitions/min) showed no effect. This neuromuscular excitation may reduce electromechanical delay, shorten the transition phase of the stretch-shortening cycle, and facilitate rapid force transmission from muscle to bone, thereby enhancing power output, improving jump performance, and enabling a rapid and forceful response to environmental disturbances to maintain balance48,50. However, in this study, the improvements in vertical jump and balance performance following DS did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that the stretching frequency (20 repetitions/min) may have been insufficient to elicit the PAPE fully.

Practical applications

The findings of this study indicate that prolonged SS, DS, and PNF stretching effectively enhance flexibility in contemporary dancers with high baseline flexibility. Notably, the flexibility gains from DS and PNF persist for longer. Furthermore, SS and PNF stretching did not negatively impact muscle performance in dancers. To minimize any potential adverse effects of SS and PNF stretching, allowing at least a 5-minute recovery period between stretching and subsequent performance or training is recommended. Additionally, contemporary dancers are encouraged to incorporate higher-frequency DS before training or competition to optimize flexibility while preserving or enhancing muscle performance. This strategy may help maintain neuromuscular readiness and improve technical execution during performances.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study only assessed the effects of single stretching modalities (SS, DS, and PNF). It did not examine the potential synergistic effects of combining different stretching techniques (e.g., SS combined with DS). Such combinations further enhance the benefits of stretching through complementary mechanisms. Future research should explore the efficacy of combined stretching strategies, as this remains an underexplored area. Additionally, this study focused on short-term effects within 15 min post-stretching. While this timeframe is relevant for dancers preparing for performances, it does not capture potential long-term adaptations. Given that previous studies have indicated that ROM improvements induced by stretching tend to stabilize or even slightly decline over time, future research should extend the assessment period to 30 min or even one hour. This would help clarify the temporal dynamics of stretching effects over longer durations, providing more explicit guidance on the optimal timing between stretching and subsequent performance for dancers.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ko, M. G., Lee, M. M. & Song, C. H. A comparison of the effects of different stretching methods on flexibility, muscle activity, and pain threshold in Ballet dancers; a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 24, 354–360 (2020).

Kenny, S. J., Whittaker, J. L. & Emery, C. A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal injury in preprofessional dancers: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 997–1003 (2016).

Behm, D. G., Alizadeh, S., Daneshjoo, A. & Konrad, A. Potential effects of dynamic stretching on injury incidence of athletes: A narrative review of risk factors. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ. 53, 1359–1373 (2023).

Konrad, A., Stafilidis, S. & Tilp, M. Effects of acute static, ballistic, and PNF stretching exercise on the muscle and tendon tissue properties. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 27, 1070–1080 (2017).

Konrad, A., Budini, F. & Tilp, M. Acute effects of constant torque and constant angle stretching on the muscle and tendon tissue properties. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 117, 1649–1656 (2017).

Opplert, J., Genty, J. B. & Babault, N. Do stretch durations affect muscle mechanical and neurophysiological properties? Int. J. Sports Med. 37, 673–679 (2016).

Takeuchi, K., Nakamura, M., Matsuo, S., Akizuki, K. & Mizuno, T. Effects of speed and amplitude of dynamic stretching on the flexibility and strength of the hamstrings. J. Sports Sci. Med. 21, 608–615 (2022).

Gesel, F. J., Morenz, E. K., Cleary, C. J. & LaRoche, D. P. Acute effects of static and ballistic stretching on muscle-tendon unit stiffness, work absorption, strength, power, and vertical jump performance. J. Strength. Cond Res. 36, 2147–2155 (2022).

Behm, D. G., Kay, A. D., Trajano, G. S. & Blazevich, A. J. Mechanisms underlying performance impairments following prolonged static stretching without a comprehensive warm-up. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 121, 67–94 (2021).

Blazevich, A. J. et al. No effect of muscle stretching within a full, dynamic warm-up on athletic performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 50, 1258–1266 (2018).

Montalvo, S. et al. Effects of different stretching modalities on the antagonist and agonist muscles on isokinetic strength and vertical jump performance in young men. J. Strength. Cond Res. 39, 173–183 (2025).

Wang, B. et al. Neuromuscular and balance adaptations following acute stretching exercise: A randomized control trial. Front. Physiol. 15, 1486901 (2024).

Araya-Ibacache, M. et al. Dynamic stretching increases the eccentric rate of force development, but not jump height in female volleyball players. J. Hum. Kinet. 84, 158–165 (2022).

Matsuo, S. et al. Changes in flexibility and force are not different after static versus dynamic stretching. Sports Med. Int. Open. 3, E89–E95 (2019).

Haddad, M. et al. Dynamic stretching alone can impair slower velocity isokinetic performance of young male handball players for at least 24 hours. PloS One. 14, e0210318 (2019).

Behm, D. G. & Chaouachi, A. A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 111, 2633–2651 (2011).

Morrin, N. M. & Redding, E. Acute effects of warm-up stretch protocols on balance, vertical jump height, and range of motion in dancers. J. Dance Med. Sci. 17, 34–40 (2013).

Lima, C. D. et al. Acute effects of static vs. Ballistic stretching on strength and muscular fatigue between Ballet dancers and Resistance-Trained women. J. Strength. Cond Res. 30, 3220–3227 (2016).

Rubini, E. C. et al. Immediate effect of static and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on hip adductor flexibility in female Ballet dancers. J. Dance Med. Sci. Off Publ Int. Assoc. Dance Med. Sci. 15, 177–181 (2011).

Opplert, J. & Babault, N. Acute effects of dynamic stretching on muscle flexibility and performance: an analysis of the current literature. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ. 48, 299–325 (2018).

Amiri-Khorasani, M., Mohammadkazemi, R., Sarafrazi, S., Riyahi-Malayeri, S. & Sotoodeh, V. Kinematics analyses related to stretch-shortening cycle during soccer instep kicking after different acute stretching. J. Strength. Cond Res. 26, 3010–3017 (2012).

Taylor, D. C., Dalton, J. D., Seaber, A. V. & Garrett, W. E. Viscoelastic properties of muscle-tendon units. The Biomechanical effects of stretching. Am. J. Sports Med. 18, 300–309 (1990).

Gajdosik, R. L. Passive extensibility of skeletal muscle: review of the literature with clinical implications. Clin. Biomech. Bristol Avon. 16, 87–101 (2001).

Ford, P. & McChesney, J. Duration of maintained hamstring ROM following termination of three stretching protocols. J. Sport Rehabil. 16, 18–27 (2007).

Behm, D. G., Blazevich, A. J., Kay, A. D. & McHugh, M. Acute effects of muscle stretching on physical performance, range of motion, and injury incidence in healthy active individuals: A systematic review. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41, 1–11 (2016).

Sharman, M. J., Cresswell, A. G. & Riek, S. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: mechanisms and clinical implications. Sports Med. Auckl. NZ. 36, 929–939 (2006).

Zaidi, S. et al. Immediate and long-term effectiveness of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and static stretching on joint range of motion, flexibility, and electromyographic activity of knee muscles in older adults. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2610 (2023).

Mitchell, U. H. et al. Neurophysiological reflex mechanisms’ lack of contribution to the success of PNF stretches. J. Sport Rehabil. 18, 343–357 (2009).

Mizuno, T., Matsumoto, M. & Umemura, Y. Decrements in stiffness are restored within 10 min. Int. J. Sports Med. 34, 484–490 (2013).

Železnik, P., Jelen, A., Kalc, K., Behm, D. G. & Kozinc, Ž. Acute effects of static and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on hamstrings muscle stiffness and range of motion: A randomized cross-over study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 124, 1005–1014 (2024).

Nakamura, M., Ikezoe, T., Tokugawa, T. & Ichihashi, N. Acute effects of stretching on passive properties of human gastrocnemius Muscle-Tendon unit: analysis of differences between Hold-Relax and static stretching. J. Sport Rehabil. 24, 286–292 (2015).

Herda, T. J. et al. The effects of dynamic stretching on the passive properties of the muscle-tendon unit. J. Sports Sci. 31, 479–487 (2013).

Mizuno, T. & Umemura, Y. Dynamic stretching does not change the stiffness of the Muscle-Tendon unit. Int. J. Sports Med. 37, 1044–1050 (2016).

Daneshjoo, A., Hosseini, E., Heshmati, S., Sahebozamani, M. & Behm, D. G. Effects of slow dynamic, fast dynamic, and static stretching on recovery of performance, range of motion, balance, and joint position sense in healthy adults. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 16, 167 (2024).

Barboza, E. Z. et al. Rehabilitation technique of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation applied to volleyball vertical jump: A randomized double blinded cross-over clinical trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 40, 2130–2135 (2024).

Konrad, A., Seiberl, W., Tilp, M., Holzer, D. & Paternoster, F. K. What to stretch? - isolated proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching of either quadriceps or triceps Surae followed by post-stretching activities alters tissue stiffness and jump performance. Sports Biomech. 23, 2798–2815 (2024).

Donti, O. et al. Acute and long-term effects of two different static stretching training protocols on range of motion and vertical jump in preadolescent athletes. Biol. Sport. 38, 579–586 (2021).

Yu, W. et al. Examining the influence of warm-up static and dynamic stretching, as well as post-activation potentiation effects, on the acute enhancement of gymnastic performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. Med. 23, 156–176 (2024).

Moltubakk, M. M., Magulas, M. M., Villars, F. O., Seynnes, O. R. & Bojsen-Møller, J. Specialized properties of the triceps Surae muscle-tendon unit in professional Ballet dancers. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 28, 2023–2034 (2018).

Babault, N., Bazine, W., Deley, G., Paizis, C. & Lattier, G. Direct relation of acute effects of static stretching on isokinetic torque production with initial flexibility level. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 10, 117–119 (2015).

Behm, D. G., Bambury, A., Cahill, F. & Power, K. Effect of acute static stretching on force, balance, reaction time, and movement time. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36, 1397–1402 (2004).

Costa, P. B., Graves, B. S., Whitehurst, M. & Jacobs, P. L. The acute effects of different durations of static stretching on dynamic balance performance. J. Strength. Cond Res. 23, 141–147 (2009).

Amara, S., Bouguezzi, R., Chaabene, H. & Mkaouer, B. Acute effect of short-duration static stretching exercises on dynamic balance in U-14 female athletes. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 26, 37–44 (2024).

Huang, S., Zhang, H. J., Wang, X., Lee, W. C. C. & Lam, W. K. Acute effects of soleus stretching on ankle flexibility, dynamic balance and speed performances in soccer players. Biology 11, 374 (2022).

Yin, Y. et al. Effect of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on patients with chronic ankle instability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 20, e0311355 (2025).

Lima, D., Ruas, C., Behm, C. & Brown, L. D. Acute effects of stretching on flexibility and performance: A narrative review. 1, 29–37 (2019).

Melocchi, I. et al. Effects of different stretching methods on vertical jump ability and range of motion in young female artistic gymnastics athletes. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 61, 527–533 (2021).

Gollhofer, A. & Rapp, W. Recovery of stretch reflex responses following mechanical stimulation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 66, 415–420 (1993).

Fletcher, I. M. The effect of different dynamic stretch velocities on jump performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 109, 491–498 (2010).

Chatzopoulos, D., Galazoulas, C., Patikas, D. & Kotzamanidis, C. Acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on balance, agility, reaction time and movement time. J. Sports Sci. Med. 13, 403–409 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Yuqiang Mai for his initial contributions to this research project.

Funding

Guangdong Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Regularization Project 2022 (GD22CTY09): Research on the Coordinated Development Path of International Competitiveness in Sports in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RX and GS participated in the conception or design, acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data, and drafting and revising the manuscript. GS and WW participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. YH, PP participated in revising the manuscript and supervision. JS, PP, and DY participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of authorship.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Sport University (Approval No: 2023LCLL-75).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, R., Lin, G., Peng, W. et al. Time-dependent effects of acute stretching on power, balance, and flexibility in contemporary dancers: a randomized crossover trial. Sci Rep 15, 15489 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00027-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00027-0