Abstract

Neonatal hypoxia, a prevalent complication during the perinatal period, poses a serious threat to the health of newborns. The intestine, as one of the most metabolically active organs under stress conditions, is particularly vulnerable and susceptible to hypoxic injury. Using a neonatal hypoxic mouse model, we systematically investigated hypoxia-induced intestinal barrier damage and underlying mechanisms. Hypoxia caused significant structural abnormalities in the ileum and distal colon of neonatal mice, including increased numbers of F4/80+ cells (p = 0.0031), swollen mucus particles (p = 0.0119), and disrupted tight junction. At the genetic level, hypoxia caused dysregulation of the expression of genes involved in intestinal barrier function, including antimicrobial activity, immune response, intestinal motility, and nutrient absorption. Further 16 S rDNA sequencing revealed hypoxia-driven gut microbiota dysbiosis with general reduced microbial abundance and diversity (Chao1 = 0.1143, Shannon = 0.0571, and Simpson = 0.3429). Structural dysbiosis of the gut microbiota consequently perturbed metabolic homeostasis, especially enhancing the activity of glycolipid metabolism. Notably, results showed that hypoxia may interfere with neurotransmitter metabolism, thereby increasing the risk of neurological disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neonatal hypoxia, a common complication occurring during the perinatal period, poses a severe threat to neonatal health. It can not only lead to acute symptoms such as death, cardiac arrest, and metabolic disorders but also trigger chronic sequelae encompassing cerebral palsy, epilepsy, intellectual disability, cognitive and behavioral deficits. A multitude of factors including infections, heat stress, preeclampsia, abnormal delivery processes and their complications, maternal hypoxia, and respiratory failure, can create conditions conducive to neonatal asphyxia, thereby challenging the development and function of multiple systems1,2,3,4,5. Furthermore, neonatal hypoxia exerts a deleterious impact on various organs, including the myocardium, kidneys, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract, leading to widespread tissue damage. As the pivotal organ, the intestine fulfills essential roles in nutrient uptake, waste elimination, toxin detoxification, and serves as a critical immune and endocrine organ6. During the neonatal period, the intestine is particularly vulnerable and susceptible to injury. Among premature neonates suffering from neonatal hypoxia, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) emerges as a leading cause of early neonatal demise, characterized by necrosis of the intestinal mucosa and submucosa7,8.

In recent years, there has been a growing research focus on the implication of hypoxia on the intestinal microenvironment and the crucial role of the intestine in neonatal development. In diverse pathological symptoms related to hypoxia, such as acute mountain sickness9,10,11,12, intrauterine hypoxia13, and intermittent hypoxia as seen in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome (OSAS), perturbations in the gut microbiota diversity and composition have been documented. These findings implicate hypoxia as a potential contributor to gut microbiota disturbances. Notably, studies have demonstrated that antibiotic-mediated depletion of gut microbiota can mitigate intestinal damage caused by hypoxia9, further corroborating a causal link between hypoxia and intestinal injury. Moreover, given the close interplay between the intestine and other organs, intestinal damage is likely interconnected with dysfunction in distant organs. For instance, both non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease are thought to be associated with disruption in the gut-liver axis through the gut microbiota14. Several neurological disorders, including Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and autism, have also been linked to gut-brain axis microbiota dysfunction15,16,17,18,19, with evidence suggesting a connection between leaky gut and social impairments in humans20. The integrity of the intestinal barrier, structurally and functionally, is generally regarded as a modulator of interactions between the intestine and other systems14,21. Numerous studies have reported that neonatal hypoxia results in gut bacterial translocation and subsequent remote organ damage, highlighting the interconnectedness between the intestinal microenvironment and other systems and organs. Thus, could the spectrum of neonatal diseases stemming from hypoxia be attributed to intestinal damage? During early life stages, the composition of the gut microbiota is dynamic and influenced by a complex interplay of host and environmental factors22. How does neonatal hypoxia perturb the microbiota and affect intestinal barrier function? Could the modulation of gut microbiota represent a viable strategy to prevent further intestinal and systemic organ damage resulting from neonatal hypoxia? Consequently, elucidating the impact of neonatal hypoxia on the intestinal microenvironment is of paramount importance.

To delve into this issue, this project will employ a neonatal hypoxia mouse model to mimic the hypoxic conditions experienced by humans during the 23rd to 32nd weeks of gestation and conduct a comprehensive assessment of hypoxia’s effects on intestinal function from multiple perspectives within the intestinal microenvironment, to provide insights and references for clinical diagnosis and treatment.

Materials and methods

Construction of the neonatal hypoxia model

All procedures strictly adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Hangzhou Normal University. The pregnant C57BL/6 inbred mice (n = 6) at gestational day 12 (GD12) were purchased from the China National Laboratory Animal Research Center (Shanghai, China) were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle (22 ± 2◦C) and fed with a standard chow diet and water. The cages and water bottles were sterilized every day. Pregnant mice were allowed to deliver spontaneously, with litter sizes ranging from 6 to 10 pups per cage, and the body weight of the offspring was measured with a precision of 0.01 g on day 3 prior to the experimental procedures. Individuals exhibiting notably low body weight were excluded from being utilized as experimental specimens for subsequent investigations. Then mice pups with their mother were subjected to chronic sublethal hypoxia [10% fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)] starting at postnatal day 3 to day 10. Hypoxic mice pups were compared to normoxic mice at postnatal Days 10. At least 6 mice per group were used for all experiments. All endeavors were made to minimize the suffering of the animals involved in the experiment.

Histological analyses

The ileal and distal colonic tissues obtained from the normoxia and hypoxia groups were fixed with paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin paraffin-embedded and then cut into 5-µm thick sections. These sections were then deparaffinized and stained with haematoxylin & eosin (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) and examined under a microscope (Leica, DM6B, Germany). Glycan detection was performed through periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and alcian blue (AB) (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) staining to visualize the general intestinal carbohydrate moieties.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA from ileum and colon was extracted separately using the RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Dalian). The concentration, quality, and integrity of the RNA was assessed by Bioteke ND5000 instrument (Bioteke Scientific, Beijing, China). The cDNA was synthesized using HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+ gDNA wiper) kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) in a MasterCycler thermocycler (CFX96, Bio-Rad) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The relative mRNA levels of the genes were shown after normalized to those of Gapdh. The primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China), and the detailed primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence staining

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analyses were adopted as previously described23. Briefly, for the immunohistochemical analysis, the deparaffinized tissue sections were subjected to antigen retrieval, blocking of endogenous peroxidase, 3% bovine serum albumin blockage and incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-F4/80 (1:500, Servicebio) over night at 4 °C. On the next day, appropriate secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies were used at room temperature (RT, 20–25 °C) for 1 h. The sections were developed using 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and counterstained using haematoxylin. For the immunofluorescence assay, the deparaffinized tissue sections were subjected to 5% goat serum with 0.1% TritonX-100 blockage, followed by incubation with the rabbit anti-ZO-1 (1:200, Servicebio) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjucted goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) as secondary antibody and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

16 S rDNA sequencing and data analysis

Microbial genomic DNA was extracted from colon contents using the GHFDE100 DNA isolation kit (GUHE, Hangzhou, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. After quantified and characterized, the 16S rRNA genes V4 region of the extracted DNA was amplified using the forward primer 515F (5’- GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and the reverse primer 806R (5’- GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’). The amplicons were pooled, purified, and sequenced using the NovaSeq6000 platform at GUHE Info Technology Co., Ltd (Hangzhou, China). Sequence data analyses were mainly performed using QIIME2 and R packages (v3.6.3). Statistical analyses of sample variations were performed using PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) to quantify the contribution (R² value) of various grouping factors to the observed differences, while the statistical significance (p-value) of these contributions was assessed through permutation testing. Taxa abundances at the phylum, class, order, family, genus and species levels were statistically compared among groups by Kruskal–Wall is rank-sum test from R stats package. All statistical tests P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The identification of microbial biomarkers was used linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe; version 1.0), and the impact of the differences in the abundance of each species was assessed by linear discriminant analysis (LDA). Function prediction analysis (KEGG enzymes and MetaCyc pathway) was performed using PICRUSt2 according to KEGG database24,25,26. The output file was further analyzed using Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP) software package v2.1.3.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 software. Two-group comparisons were performed with unpaired Student’s t-test, and P values were reported. The results were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

Hypoxia-Induced multidimensional pathological changes in intestinal tissue of neonatal mice

Ileum and distal colon tissues were collected on day P10 and subjected to histochemical staining for examination (Fig. 1A). H&E staining revealed that hypoxia-induced significant localized abnormalities in the fold morphology of the distal colon, including irregular epithelial structure and the disappearance of typical crypt structure (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the examination of ileum tissues showed a marked decrease in the number of long villi, an increase in the size of absorptive cells, and an elevated number of goblet cells (Fig. 1B).

F4/80 histochemical staining of distal colonic tissue sections revealed a significant increase in macrophage inflammatory indices in the hypoxia mice compared to the control group (p = 0.0031) (Fig. 2A and B), providing strong evidence that hypoxia induces tissue inflammation. Furthermore, AB-PAS staining showed that, compared to normoxia mice, hypoxia mice exhibited an increase in acidic mucins (blue) and an enlargement of mucus granule size in the colon significantly (p = 0.0119) (Fig. 2C and D). Additionally, immunofluorescence staining for zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a key member of the tight junction complex in the intestinal barrier, showed robust and continuous expression in the epithelial cell layer of the control group while decrease and discontinuous expression in the hypoxia group (Fig. 2E), which suggests impaired intestinal barrier integrity.

Histochemical staining of colon tissue section. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for macrophage marker protein F4/80. (B) Statistical analysis of relative positive area based on the staining in panel. (C) AB-PAS staining, where acidic mucus appears light blue, and glycogen and neutral mucus appear violet. (D) Statistical analysis of mucus granule size based on the staining in panel. (E) Scale bars are indicated in the figures. E. Immunofluorescence staining for the tight junction protein ZO-1.

Hypoxia disrupts transcriptional landscapes governing intestinal barrier function

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying hypoxia-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction, we conducted an analysis of mRNA expression in key functional genes (Fig. 3A).

Changes in the transcription levels of the genes are related to the structure and function of the intestinal barrier in the ileum or colon. (A) The schematic diagram of functional genes was created with Microsoft® PowerPoint® 2016MSO (version 2503 Build 16.0.18623.20208). (B) Bar chart of the relative mRNA levels of genes.

Antimicrobial peptide-associated genes in ileum

Significant downregulation was observed in Lyz (p = 0.004), Ang4 (p = 0.0434), and Defa20 (p = 0.0072), whereas Defa3 exhibited a marked upregulation (p = 0.0398). Although Defa5 showed an upward trend, its alteration lacked statistical significance. No significant changes were detected in Defa5 or Pla2g4a expression (Fig. 3B). These transcriptional shifts collectively indicate compromised intestinal antibacterial capacity and immune defense. Hypoxia exposure differentially modulated the expression of ileum antimicrobial peptide genes.

Ion transport-related genes in ileum

Transcriptional profiling about ion transport-related genes revealed distinct regulatory patterns. Upregulated genes included Cftr (p = 0.0097) and Nhe3 (p = 0.0099), both showing statistically significant increases, while Slc26A6 displayed a non-significant upward trend. Conversely, Nkcc1 and Slc26A3 were downregulated, with Nkcc1 reduction reaching significance (p = 0.0282). This bidirectional regulation suggests hypoxia-induced ionic imbalance in intestinal epithelium.

Inflammatory cytokine-related genes in colon

Pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17, IL-1β, IFN-γ) were uniformly upregulated post-hypoxia (p = 0.0218, p = 0.0302, p = 0.0065, p = 0.0236, p = 0.0402, separately), confirming intestinal inflammatory activation.

Endocrine-associated genes in colon

Hypoxia significantly attenuated the expression of key endocrine regulators, including Instl5 (p = 0.0227) and Neurog3 (p = 0.0181), with Sct showing a non-significant downward trend. In contrast, Agr2 expression was notably elevated (p = 0.007).

Goblet cell maturation and mucus secretion-related genes in colon

Goblet cell maturation marker Klf4 was significantly reduced (p = 0.0428), accompanied by dysregulated mucus secretion genes, Muc2/3 were significant upregulated (p = 0.031, p = 0.0298, separately) whereas Meprin-β was downregulated (p = 0.0124).

Tight junction complex genes in colon

All examined tight junction-associated genes, including ZO-1, Cldn1, Cldn2, Cldn4 and Ocln, exhibited significant transcriptional suppression (p = 0.0378, p = 0.0178, p = 0.039, p = 0.0437, separately), indicating hypoxia-induced disruption of intestinal mucosal barrier integrity. This compromised junctional architecture likely facilitates pathogenic infiltration and inflammatory cascade initiation.

Hypoxia led to disruption in gut microbiota composition and changes in microbial metabolism

To evaluate the impact of hypoxia on the gut microbiota in neonatal mice, 16 S rDNA sequencing was performed. As identified using weighted UniFrac principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), hypoxia altered the microbiota structure of neonatal mice. It is clearly observable that the confidence ellipse of the bacterial community in the neonatal hypoxia group has a significant deviation compared to the normoxia control group (R2 = 0.5809, p-value = 0.035), with only a minimal overlap, and there is greater heterogeneity among the samples within the neonatal hypoxia group, which indicating distinctive microbiota structures (Fig. 4A). Additionally, the overall microbial community could be statistically distinguishable between hypoxia and normoxia control groups (ANOSIM Global R = 0.469, P = 0.072) (Fig. 4B). The observed species and the richness reflected by the Chao1 index (0.1143), and the diversity and evenness represented by the Shannon (0.0571) and Simpson (0.3429) indexes of the gut microbiota were all affected by neonatal hypoxia, although the decrease is not significant (Fig. 4C). The top 10 micro-organisms at the family level are shown in Fig. 4D. The dominant microbiota constituents of the two samples at the family level were Pasteurellaceae and Bacteroidaceae. The relative abundance of Bac_Prevotellaceae, Vei_Selenomonadaceae, Bur_Sutterellaceae and Pas_Pasteurellaceae decreased significantly and that of Lac_Lactobacillaceae increased significantly after neonatal hypoxia (Fig. 4E).

Analysis of Community Composition of the gut microbiota in mice. (A) UniFrac principal co-ordinate analysis (PCoA) (n = 4). Each point in the figure represents a sample, and points of the same color belong to the same group. The distance between points reflects the similarity between samples. (B) Anosim test result for β-diversity is used to examine whether the differences between groups are significantly greater than the differences within groups, thereby determining the significance of the grouping. (C) Boxplot of α-diversity analysis (Shannon, Simpson, and Chao1 index) is used to assess the richness and diversity of microbial species within samples. (D) Bar chart of the top 10 species in terms of relative abundance at the family level. The horizontal axis represents samples, and the vertical axis represents relative abundance. “Others” indicates the sum of the relative abundances of all families not included in these top10. (E) Five families with significant differences. Values are presented as means ± SEM (n = 4).

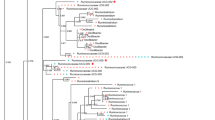

LEfSE (LDA Effect Size) analysis (LDA score > 2) analysis presents the dominant markers with significant differences between groups (Fig. 5A). The enriched taxa in the control and CTL exposure microbiota (from colon contents) are represented through a cladogram (Fig. 5B). Based on the Bugbase tool’s prediction of microbiota phenotypic characteristics, there are significant differences between the two groups in the phenotypic features of aerobic (oxygen-requiring), contains mobile elements, and potentially pathogenic (Fig. 5C).

LEfSE (LDA Effect Size), Bugbase and PICRUSt 2 analyses. (A) The LDA score and enriched taxa of the intestinal microbiota after neonatal hypoxia, compared with normoxia. The colors of the bars represent different groups, while the lengths of the bars indicate the LDA scores, reflecting the degree of impact of significantly different species between different groups. (B) The enriched taxa in the control and neonatal hypoxia microbiota are represented through a cladogram. In the evolutionary tree plot, the circles radiating from the inside out represent taxonomic levels from phylum to genus. Each small circle at different taxonomic levels represents a classification at that level, and the diameter of the small circle is proportional to its relative abundance. Coloring principle: Species without significant differences are uniformly colored yellow, while Biomarker species with differences are colored according to their respective groups. Red nodes indicate microbial taxa that play an important role in the red group, and green nodes indicate microbial taxa that play an important role in the green group. The species names represented by English letters are displayed in the legend on the right (for aesthetic purposes, only the different species from phylum to family are displayed by default on the right). Note: The species names represented by English letters are also displayed in the legend at the bottom of the figure. (C) Phenotypic characteristic analysis of Bugbase tool’s prediction. The three lines in the graph, from top to bottom, represent the upper quartile, mean, and lower quartile, respectively. (D) The predicted differences in the KEGG metabolic pathways (Shown top 10). (E) The predicted differences in the GBM (Gut-Brain) metabolic pathways (Shown top 10).

Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States2 (PICRUSt2) was further used to predict the metabolic functions of the changed microbe (Show only the top 10). Cluster analysis of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway revealed the difference of the key target genes primarily on the metabolic pathway of glucose and fatty acid. Specifically, it includes glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), pentose phosphate pathway, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, fructose and mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, ascorbate and alternate metabolism, fatty acid biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, synthesis and degradation of ketone bodies between the two groups (Fig. 5D). And the reads abundance related to these pathways has significantly increased after hypoxia. Given that hypoxia is a significant inducer of neonatal encephalopathy, leading to arrested myelination in the brain, the KO gene annotations of the pathways were further translated into the results of neurotransmitter-related gene modules (GBM) using the omixer-rpm tool. Genes related to inositol synthesis, quinolinic acid degradation, isovaleric acid synthesis II (KADC pathway), S-Adenosylmethionine(SAM) synthesis, butyrate synthesis I, GABA degradation, glutamate synthesis I, ClpB (ATP-dependent chaperone protein), acetate synthesis II, dopamine degradation, acetate synthesis III, acetate synthesis I were significantly upregulated (Fig. 5E). Based on aforementioned findings, a general significant upregulated has been observed in the gene mapping of relevant metabolic pathways, suggesting an increase in the metabolic activity of the gut microbiota following hypoxia.

Discussion

Our study revealed that neonatal mice subjected to hypoxic conditions developed significant pathological alterations in both ileum and colonic tissues, indicating that hypoxia may disrupt normal intestinal development and induce tissue-specific structural and functional impairments. The apparent changes in mucus particle size and mucus properties may reflect abnormal development of goblet cells and mucus secretion27 Interestingly, these observed mucin secretory disturbances and modifications in mucus characteristics mirror pathological responses typically associated with infectious enteropathies, where goblet cell proliferation and enhanced mucus production serve as protective mechanisms to shield damaged mucosa or facilitate pathogen entrapment and clearance. Emerging evidence indicates that goblet cell dysgenesis is closely associated with dysregulation of WNT and NOTCH signaling pathways. Enhanced WNT signaling leads to excessive proliferation of secretory progenitors28. Conversely, inhibition of NOTCH signaling results in a dramatic shift toward secretory lineage differentiation, particularly favoring goblet cell expansion29. This bidirectional regulatory axis offers novel therapeutic perspectives: targeted modulation of WNT/NOTCH signaling demonstrates mucosal repair potential in goblet cell-deficient pathologies like ulcerative colitis30, whereas selective inhibition of pathway components may restore epithelial homeostasis in hyperplastic conditions. Deciphering the regulatory mechanisms governing goblet cell differentiation and mucus secretion holds substantial clinical significance for developing precision therapeutic strategies.

Hypoxia-induced changes in transcription levels of functional genes in the ileum and colon revealed multidimensional molecular dysregulation. Immune homeostasis imbalance shows overall downregulation of antimicrobial peptide-related genes, indicating impaired intestinal innate immune defense, while upregulated pro-inflammatory cytokine genes demonstrate aberrant activation of inflammatory cascades. This molecular signature corroborates histopathological findings showing increased infiltration of F4/80-positive macrophages. Disordered ion transporter gene expression may disrupt luminal electrolyte balance, contributing to malabsorption and pro-inflammatory microenvironment formation. The dysregulated expression of core mucin genes (Muc1/2/3) in goblet cells, combined with suppressed Meprin-β (essential for Muc2 proteolytic processing)31, creates a mucus production-degradation imbalance. This pathophysiological alteration correlates with AB-PAS staining observations of enlarged mucus granules and modified mucus properties consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathology. In addition, Hypoxia significantly suppresses insulin-like peptide 5 (Insl5), an orexigenic hormone specifically expressed by colonic enteroendocrine cells (EECs)32. This regulatory mechanism, as well as multiple intestinal injuries, may explains the observed weight loss seen in hypoxic-mice (data not shown). And the diminished Neurog3 expression in EEC progenitor triggers lineage differentiation bias, driving abnormal goblet cell proliferation and resulting in pathological thickening of the mucus layer33. Concurrently, activation of the Agr2 pathway reflects endoplasmic reticulum stress, collectively disrupting EECs’ hormonal secretion homeostasis and ultimately creating a vicious cycle that accelerates intestinal pathological progression34. Downregulation of tight junction components, suggesting compromised epithelial junction structures that may increase intestinal permeability. This defect could facilitate luminal pathogen translocation and systemic inflammation propagation. Taking ZO-1 as an example, the results of immunofluorescence staining also confirmed the decrease in transcription levels.

The normal structure and functional operation of the intestine are inseparable from a healthy gut microbiota. The gut microbiota plays multiple roles, with functions encompassing the digestive process and nutrient absorption, regulation of immune responses, protection of the intestinal barrier, interaction and communication with the nervous system, as well as the precise regulation of metabolic processes. The development and progression of a multitude of diseases are intricately tied to disruption in the gut microbiota, underscoring the importance of maintaining gut microbiota homeostasis in promoting overall health. Following neonatal hypoxia, alterations in the gut microbiota of mice have revealed significant changes in the abundance of dominant bacterial taxa, with the family Prevotellaceae in the colon being closely linked to the onset and progression of various diseases. Specifically, studies have demonstrated a strong positive correlation between Prevotellaceae and the occurrence of Autism Spectrum Disorder(ASD)35,36. Children diagnosed with ASD exhibit a reduced abundance of Prevotellaceae37,38. Similarly, decreased levels of Prevotellaceae have also been observed in patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PD)38 and Multiple Sclerosis39,40. The potential mechanism underlying the association between this bacterial family and neurological diseases may involve the inhibition of arginine metabolism due to the reduction of Prevotellaceae, leading to elevated levels of nitric oxide, which could contribute to abnormal neurodevelopment and the pathogenesis of ASD. Additionally, a lack of Prevotellaceae has been reported in individuals with hypertension41. Furthermore, variations in the abundance of Sutterellaceae within the colon have been implicated in the development of conditions such as ASD, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, and possibly hypertension41. Regarding the families Selenomonadaceae and Pasteurellaceae, the impact of their reduced abundance in the colon and their specific associations with particular diseases remain incompletely understood. Notably, neonatal hypoxia induces a significant increase in the abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the mouse gut. Lactobacillaceae, which are widely present in nature and within hosts (including humans and animals), primarily participate in processes such as glycolipid metabolism. This family encompasses various probiotics that play pivotal roles in regulating gut microbiota balance, inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria, facilitating food digestion and nutrient absorption, enhancing host immunity, and combating inflammatory responses. However, alterations in their abundance within the colon may also modify the host’s metabolic state and potentially trigger diseases. The increase in the abundance of Lactobacillaceae in the gut of neonatal mice following hypoxia may be a compensatory stress response to intestinal inflammation and decreased immunity, although the exact cause remains to be elucidated.

Using PICRUSt2, it is predicted that changes in gut microbiota structure induce alterations in gene function, primarily characterized by a widespread upregulation of glycolipid metabolism activity. We hypothesize that hypoxia, as an environmental stressor, drives the gut microbiota to adjust in a direction that favors host metabolism, either by enhancing metabolic activity, altering metabolic pathways, or both, to adapt to the environmental conditions. Alternatively, hypoxia may enable certain metabolically advantageous bacteria to proliferate compensatory, thereby taking a dominant position and enhancing the metabolic capacity of the gut microbiota. It is also plausible that hypoxia indirectly affects the metabolic capacity of the gut microbiota by altering the host’s metabolic state, for instance, by inducing the production of more metabolites or regulatory factors that serve as signaling molecules to influence the metabolic activity of the gut microbiota.

Neonatal encephalopathy is one of the main complications of perinatal hypoxia, characterized by abnormal development of myelin sheaths in the central nervous system, consistent with the body tremors observed in hypoxic mice, thus neurotransmitter metabolism has received our attention. Enhanced degradation of the neurotoxin quinolinic acid42,43 and increased butyrate synthesis44 demonstrate protective antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses. Conversely, elevated S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) production (potentially from inflammatory macrophages) and accumulated isovaleric acid may exacerbate neurological symptoms45,46. Imbalanced neurotransmitter dynamics - particularly reduced GABA degradation alongside elevated glutamate synthesis - could disrupt excitation - inhibition equilibrium, increasing neurological risks47. Additionally, abnormal dopamine degradation leading to neurotransmitter depletion may contribute to Parkinsonian symptoms and mood disorders48.

During infancy, there is a rapid expansion in gut microbiota diversity, followed by a gradual slowdown. The age-differentiated microbial communities are taxonomically and functionally distinct, thus perturbation of early-life gut microbiota may contribute to subclinical inflammation that precedes childhood disease development18. Recent advancements in various metagenomic studies, coupled with epidemiological research, have enabled researchers to systematically dissect molecular bridges between specific microbial signatures and disease phenotypes, providing theoretical foundations for developing microbiota-modulating interventions such as targeted probiotic therapies49. Of particular concern, neonatal hypoxia exposure emerges as a significant developmental disruptor with profound implications for long-term health outcomes. Epidemiological evidence indicates that early-life gut dysbiosis may serve as a potential trigger for pediatric and adult-onset diseases, encompassing inflammatory bowel diseases50, immune metabolic disorders51, and even neurodevelopmental abnormalities52,53. Therefore, establishing a multidimensional longitudinal research framework post-hypoxic exposure, incorporating systematic monitoring of intestinal histopathological progression, microbiota ecological reconstitution, host growth trajectories, and neurobehavioral phenotypes, will provide crucial evidence for elucidating the intricate relationship between early environmental stressors and gut-host health homeostasis.

Data availability

Raw data from 16 S rDNA sequencing during the current study are available in the [NCBI] repository[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1243541]. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nalivaeva, N. N., Turner, A. J. & Zhuravin, I. A. Role of prenatal hypoxia in brain development, cognitive functions, and neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 12, 825. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00825 (2018).

Gale, C. et al. Neonatal brain injuries in England: population-based incidence derived from routinely recorded clinical data held in the National neonatal research database. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 103, F301–f306. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313707 (2018).

Graham, E. M. et al. A systematic review of the role of intrapartum hypoxia-ischemia in the causation of neonatal encephalopathy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199, 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.094 (2008).

Yeh, C. et al. Neonatal dexamethasone treatment exacerbates Hypoxia/Ischemia-Induced white matter injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 7083–7095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-016-0241-4 (2017).

Greco, P. et al. Pathophysiology of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review of the past and a view on the future. Acta Neurol. Belg. 120, 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-020-01308-3 (2020).

Kigbu, A. et al. Intestinal bacterial colonization in the first 2 weeks of life of Nigerian neonates using standard culture methods. Front. Pediatr. 4, 139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2016.00139 (2016).

Yin, Y. et al. Curcumin improves necrotising microscopic colitis and cell pyroptosis by activating SIRT1/NRF2 and inhibiting the TLR4 signalling pathway in newborn rats. Innate Immun. 26, 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753425920933656 (2020).

Han, N. et al. Hypoxia: the invisible pusher of gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 12, 690600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.690600 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Phospholipid metabolites of the gut microbiota promote hypoxia-induced intestinal injury via CD1d-dependent Γδ T cells. Gut Microbes. 14, 2096994. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2096994 (2022).

Gamah, M. et al. High-altitude hypoxia exacerbates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis by upregulating Th1 and Th17 lymphocytes. Bioengineered 12, 7985–7994. https://doi.org/10.1080/21655979.2021.1975017 (2021).

Vavricka, S. R., Rogler, G. & Biedermann, L. High altitude journeys, flights and hypoxia: any role for disease flares in IBD patients? Dig Dis. 34, 78–83, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1159/000442932

Anand, A. C., Sashindran, V. K. & Mohan, L. Gastrointestinal problems at high altitude. Trop Gastroenterol. 27, 147 – 53, (2006).

Sun, Y. et al. Intrauterine hypoxia changed the colonization of the gut microbiota in newborn rats. Front. Pediatr. 9, 675022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.675022 (2021).

Bauer, M. The liver-gut-axis: initiator and responder to sepsis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 28, 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000000921 (2022).

Mulak, A. & Bonaz, B. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 21, 10609–10620. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10609 (2015).

Dodiya, H. B. et al. Chronic stress-induced gut dysfunction exacerbates Parkinson’s disease phenotype and pathology in a rotenone-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 135, 104352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2018.12.012 (2020).

Cantón, R. et al. Human intestinal microbiome: role in health and disease. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. https://doi.org/10.37201/req/056.2024 (2024).

Dong, T. et al. Meconium microbiome associates with the development of neonatal jaundice. Clin. Transl Gastroenterol. 9, 182. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41424-018-0048-x (2018).

Tirone, C. et al. Gut and lung microbiota in preterm infants: immunological modulation and implication in neonatal outcomes. Front. Immunol. 10, 2910. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02910 (2019).

Parseus, A. et al. Microbiota-induced obesity requires farnesoid X receptor. Gut 66, 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310283 (2017).

Funk, M. C., Zhou, J. & Boutros, M. Ageing, metabolism and the intestine. EMBO Rep. 21, e50047. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202050047 (2020).

Rodriguez, C. et al. Faecal microbiota characterisation of horses using 16 Rdna barcoded pyrosequencing, and carriage rate of clostridium difficile at hospital admission. BMC Microbiol. 15, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0514-5 (2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. Necl-4/SynCAM-4 is expressed in myelinating oligodendrocytes but not required for axonal myelination. PLoS One. 8, e64264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064264 (2013).

Ogata, H. et al. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.1.29 (1999).

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D672-d677). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae909 (2025).

Gustafsson, J. K. & Johansson, M. E. V. The role of goblet cells and mucus in intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 785–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00675-x (2022).

Schuijers, J. & Clevers, H. Adult mammalian stem cells: the role of Wnt, Lgr5 and R-spondins. Embo j. 31, 2685-96, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/emboj.2012.149

Pellegrinet, L. et al. Dll1- and dll4-mediated Notch signaling are required for homeostasis of intestinal stem cells. Gastroenterology 140, 1230–1240e. 1-7 (2011).

van der Flier, L. G. & Clevers, H. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 71, 241 – 60, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145

Wichert, R. et al. Mucus detachment by host metalloprotease Meprin Β requires shedding of its inactive Pro-form, which is abrogated by the pathogenic protease RgpB. Cell. Rep. 21, 2090–2103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.087 (2017).

Di Vincenzo, A. et al. Body weight reduction by bariatric surgery reduces the plasma levels of the novel orexigenic gut hormone Insulin-like peptide 5 in patients with severe obesity. J. Clin. Med. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12113752 (2023).

Li, H. J. et al. Reduced Neurog3 gene dosage shifts enteroendocrine progenitor towards goblet cell lineage in the mouse intestine. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.08.006 (2021).

Yuan, S. H. et al. AGR2-mediated unconventional secretion of 14-3-3ε and α-actinin-4, responsive to ER stress and autophagy, drives chemotaxis in canine mammary tumor cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 29, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-024-00601-w (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Gut microbiota and autism spectrum disorders: a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1267721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2023.1267721 (2023).

Sun, H. et al. Autism spectrum disorder is associated with gut microbiota disorder in children. BMC Pediatr. 19, 516. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1896-6 (2019).

Palanivelu, L. et al. Investigating brain-gut microbiota dynamics and inflammatory processes in an autistic-like rat model using MRI biomarkers during childhood and adolescence. Neuroimage 302, 120899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2024.120899 (2024).

Scheperjans, F. et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 30, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26069 (2015).

Ordoñez-Rodriguez, A. et al. Changes in gut microbiota and multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054624 (2023).

Mangalam, A. K. & Murray, J. Microbial monotherapy with Prevotella histicola for patients with multiple sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 19, 45–53, (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2019.1555473

Jiang, Y. et al. Analysis of fecal microbiota in patients with hypertension complicated with ischemic stroke. J. Mol. Neurosci. 73, 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-023-02149-4 (2023).

Guillemin, G. J. Quinolinic acid: neurotoxicity. Febs J. 279, 1355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08493.x (2012).

Chen, L. M. et al. Tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism: a link between the gut and brain for depression in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 18, 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-021-02175-2 (2021).

Ge, X. et al. Butyrate ameliorates quinolinic acid-induced cognitive decline in obesity models. J. Clin. Invest. 133 https://doi.org/10.1172/jci154612 (2023).

Yu, W. et al. One-Carbon metabolism supports S-Adenosylmethionine and histone methylation to drive inflammatory macrophages. Mol. Cell. 75, 1147–1160e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.039 (2019).

Ribeiro, C. A. et al. Isovaleric acid reduces Na+, K+-ATPase activity in synaptic membranes from cerebral cortex of young rats. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 27, 529 – 40, (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-007-9143-3

Sears, S. M. & Hewett, S. J. Influence of glutamate and GABA transport on brain excitatory/inhibitory balance. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 246, 1069–1083, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/1535370221989263

Chinta, S. J. & Andersen, J. K. Dopaminergic neurons. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 37, 942–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2004.09.009 (2005).

Milani, C. et al. The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 81 https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00036-17 (2017).

Rautava, S. et al. Microbial contact during pregnancy, intestinal colonization and human disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2012.144 (2012).

Huh, S. Y. et al. Delivery by caesarean section and risk of obesity in preschool age children: a prospective cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child. 97, 610–616. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2011-301141 (2012).

Needham, B. D., Kaddurah-Daouk, R. & Mazmanian, S. K. Gut microbial molecules in behavioural and neurodegenerative conditions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 21, 717–731, (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-020-00381-0

Gacias, M. et al. Microbiota-driven transcriptional changes in prefrontal cortex override genetic differences in social behavior. Elife 5 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.13442 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32471022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jun Wen contributed to conceptualization, methodology, data management and wrote the manuscript. Yue Wu and Fengfeng Zhang contributed to the validation and formal analysis. Yanchu Wang contributed to the visualization. Aifen Yang and Wenwen Lu conducted data curation and project administration. Huaping Tao contributed to conceptualization, methodology, writing, review and editing. Xiaofeng Zhao performed the writing, review, editing, supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, J., Wu, Y., Zhang, F. et al. Neonatal hypoxia leads to impaired intestinal function and changes in the composition and metabolism of its microbiota. Sci Rep 15, 15285 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00041-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00041-2