Abstract

Myocardial cold ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury is an inevitable consequence of heart transplantation, significantly affecting survival rates and therapeutic outcomes. Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF15) has been shown to regulate GPX4-mediated ferroptosis, playing a critical role in mitigating I/R injury. Meanwhile, verbascoside (VB), an active compound extracted from the herbaceous plant, has demonstrated myocardial protective effects. In this study, heart transplantation was performed using a modified non-suture cuff technique, with VB administered at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day via intraperitoneal injection for 3 days in vivo. In vitro, cardiomyocytes were pretreated with 50 µg/ml VB for 24 h. VB treatment significantly reduced histopathological injury, decreased myocardial injury markers, and inhibited ferroptosis and oxidative stress during myocardial cold I/R injury in vivo. In vitro experiments further demonstrated that GDF15 alleviates ferroptosis induced by hypoxic reoxygenation by upregulating GPX4. Therefore, it is concluded that VB preconditioning can effectively reduce ferroptosis induced by myocardial cold I/R after heterotopic heart transplantation, possibly through up-regulation of GDF15/GPX4/SLC7A11 pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart transplantation is the ultimate treatment for patients with end stage heart disease1. The application of immunosuppressants has greatly improved the postoperative transplant rejection. However, cold I/R injury is the ineluctable cause of graft dysfunction in heart transplantation2;3. In most cases, the transport time of donor heart after removal exceeds the short safe preservation time of 4–6 h, resulting in the donor did not relieve the ischemic injury due to the recovery of blood flow, but the tissue injury was aggravated by the release of a large number of reactive oxygen species during reperfusion, called cold I/R injury, which seriously affects the therapeutic effect. This damage leads to early heart failure and even death following heart transplantation, which greatly affects the prognosis of heart transplant patients. Therefore, it is important to understand the mechanism of myocardial I/R injury and make intervention. Cold I/R injury following heart transplantation causes pathological changes such as apoptosis, inflammatory response, ferroptosis, energy metabolism disorder and oxidative stress4;5. Previous study6 showed that static cold University of Wisconsin (UW) solution is the best technique of preservation, but its protective effect is finited. Hence, new therapeutic ideas are needed to ease the cold I/R injury in heart transplantation.

Over the past several decades, traditional Chinese medicine has gained worldwide attention for its satisfactory therapeutic results7. There are studies indicated that Ginsenoside Rb1 could inhibit cardiomyocyte autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and reduce myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury8. Verbascoside (VB), as a water-soluble natural phenylethanol glycoside, is widely present in many dicotyledonous medicinal plants such as pedicularis and rehmannia, and has been proved to have anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, immunomodulatory and neuroprotective biological activities9. Moreover, multiple molecular mechanisms are involved in I/R injury, previous studies10 have shown that VB can protect endotoxin-induced septic cardiomyopathy by reducing cardiac inflammatory response, inhibiting oxidative stress and regulating mitochondrial dynamics11.

GDF15, a member of the Transforming Growth Factor β superfamily, is a stress response cytokine, which plays a role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders and neurodegeneration12;13. In addition, a clinical study has found that GDF15 plays a protective role in patients with heart failure14, however, the relationship between VB and GDF15 has not been studied. Ferroptosis is a form of iron-related programmed cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation15, and its morphology and physiological mechanism are different from the death forms of apoptosis and pyroptosis16. It has been reported that ferroptosis is closely related to the occurrence of athophysiological processes of I/R injury in different organs17. Recent studies have shown that galangin alleviated doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis through GSTP1/JNK pathway18. Based on the aforementioned findings, we hypothesized that VB alleviates myocardial I/R injury by increasing GDF15, and enhancing expressions of SLC7A11 and GPX4, in turn inhibiting myocardial ferroptosis.

Results

VB attenuated myocardial I/R injury following heterotopic heart transplantation

The chemical structure of VB is shown in Fig. 1A, and the experimental protocol as well as surgical operation is shown in Fig. 1B-C. The myocardial injury and cardiac function of the donor heart were evaluated by beating score and pathological HE staining. The results were observed that the myocardial myofibrillar loss, myocardial cell necrosis, increased vacuolation (Fig. S1 of supplementary file 2), and abnormal structure in I/R group compared with the control group (Fig. 1D), moreover, the donor heart graft beating score was decreased (Fig. 1H). At the same time, we also detected markers of myocardial injury in the serum, and found that VB treatment significantly reduced the levels of CK-MB, cTnI and LDH in serum of I/R mice (Fig. 1E-G). Recent studies have suggested that oxidative stress plays an important role in myocardial I/R injury19, therefore, we also examined the levels of SOD and MDA treated with or without VB after heart transplantation, and we found that VB promoted the production of SOD in cardiac tissue and inhibited the expression of MDA (Fig. 1I-J). Furthermore, TUNEL staining showed that VB significantly reduced the apoptosis rate of I/R injury (Fig. S2 of supplementary file 2). These results demonstrate that VB can significantly reduce the myocardial I/R injury following heart transplantation.

The protective effect of VB on I/R injury following heart transplantation in vivo. (A) The chemical structure of VB. (B) Timeline for the experimental showing drug administration, heart transplantation surgery, and killing of the mice. (C) Heart transplantation procedure. (D) HE staining representative mouse. (E–G) cTnI, CK-MB, and LDH levels in myocardial tissue. (H) Beating Scores. (I, J) Oxidative stress indicators SOD and MDA in mouse serum. Data are shown as means ± SEM, **p < 0.01.

VB treatment alleviates cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ferroptosis

The molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological processes involved in I/R injury are very complex. Autophagy damage is one of the markers of ferroptosis process, and ultrastructural images of autophagosomes in myocardial tissue were obtained by TEM. We found that VB significantly accelerated autophagosome clearance (Fig. 2A). At the same time, we detected the expression level of ferritin FTH1, which is associated with ferritinophagy (Fig. S3 of supplementary file 2). Moreover, increased levels of autophagy lead to the maturation and release of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 2B). Bax, Bcl-2 and cleaved-caspase-3 are the signature molecules of apoptosis, and we also found that pretreatment with VB significantly decreased the expression levels of Bax (Fig. 2C and D) and cleaved-caspase-3 (Fig. 2C and E) but increased the expression levels of Bcl-2 (Fig. 2C and F). Furthermore, GPX4, ACSL4, and SLC7A11 are key regulators of ferroptosis, so the results showed that VB significantly down-regulated the expression levels of ACSL4 (Fig. 2G and H), but up-regulated the expression levels of SLC7A11(Fig. 2G and I) and GPX4 (Fig. 2G, J, K and L). These results suggested that VB inhibited I/R-induced apoptosis and exerted anti-ferroptosis effect.

Effect of VB on myocardial apoptosis and ferroptosis induced by I/R injury. (A) The ultrastructural changes of mouse hearts were detected by TEM: autophagosome ( ); (B) The expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 in ischemia heart was assessed using RT-PCR; (C–F) Representative images and quantitative analysis show that pretreatment with VB prevented the I/R-induced increase in expression levels of Bax, cleaved-caspase-3 in ischemia heart tissue and the I/R-induced decrease in expression levels of Bcl-2. (G–J) Expression of ACSL4, SLC7A11 and GPX4 were quantified and shown in bar graphs. (K, L) Representative immunohistochemical staining among the 3 groups. Data are shown as means ± SEM, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

); (B) The expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 in ischemia heart was assessed using RT-PCR; (C–F) Representative images and quantitative analysis show that pretreatment with VB prevented the I/R-induced increase in expression levels of Bax, cleaved-caspase-3 in ischemia heart tissue and the I/R-induced decrease in expression levels of Bcl-2. (G–J) Expression of ACSL4, SLC7A11 and GPX4 were quantified and shown in bar graphs. (K, L) Representative immunohistochemical staining among the 3 groups. Data are shown as means ± SEM, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Effects of VB pretreatment on H9c2 lipid peroxidation and apoptosis under H/R treatment

As shown in the results, VB increased cell viability and reduced the activity of LDH in H/R-treated cardiomyocytes. With the increase of VB, cell viability enhanced, but the addition of VB 70 µg/mL compared with VB 50 µg/mL found that the increase of cell viability was not significant and there was no significant statistical difference. Therefore, we chose the concentration of 50 µg/mL in the subsequent experiment (Fig. 3A,B). Proinflammatory cytokines were detected using RT-PCR (Fig. 3C). The mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were all markedly elevated in the H/R group than in the control group and H/R + VB group. Further evidence was obtained from ROS changes, which is another oxidative stress marker (Fig. 3D–G). TUNEL assays showed that pretreatment with VB remarkably prevented the H/R-induced increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells in H9c2 (Fig. 3H,I).

Effect of VB on H/R-induced injury in vitro. (A) The dose-response effects of VB were measured using CCK8 kits; (B) The activity of LDH from each group in vitro; (C) Quantitative analysis shows that pretreatment with VB prevented the H/R-induced increase in the expression levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 mRNA. (D, E) The ROS production was detected by DCFH-DA assay; (F, G) Oxidative stress indicators MDA and SOD in cell; (H, I) Analysis of TUNEL staining results. Data are shown as means ± SEM, **p < 0.01.

VB inhibited cold H/R-induced ferroptosis and the expression of related protein

The influence of VB on ferroptosis was validated in vitro using cold H/R cell model. VB significantly decreased the intracellular Fe2+ production (Fig. 4A,B). Meanwhile, the remarkable decreased GSH (Fig. 4C) caused by cold H/R were greatly reversed after using VB. In addition, we also tested the expressions of ACSL4, SLC7A11 and GPX4. As shown in Fig. 4D–G, H/R obviously decreased SLC7A11 and GPX4 protein levels and increased ACSL4 compared with Normal. The levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4 in H/R + VB group were higher than those in H/R group, and ACSL4 lower than H/R group. Additionally, the expressions of GPX4 were further detected by immunofluorescence (Fig. 4H,I). Compared with Normal group, the expressions of GPX4 were significantly decreased in H/R group, while VB reversed the effect.

Effect of VB on ferroptosis induced by cold H/R injury. (A, B) The Fe2+ level in cells were validated; (C) The levels of GSH in the cells were measured; (D–G) The expression levels of ACSL4, SLC7A11 and GPX4 in each group using western blot; (H, I) Representative immunofluorescence staining among the 4 groups. Data are shown as means ± SEM, **p < 0.01.

VB attenuates ferroptosis induced by H/R injury dependent on the upregulation of GDF15

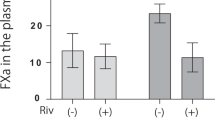

We infered that VB attenuates ferroptosis via upregulating GDF15, so we transfected si-GDF15 to silence GDF15 expression (Fig. 5I-J). At first, we uploaded the three-dimensional structure (Fig. 5A) of GDF15 from https://www.uniprot.org/. Next, we searched proteins (Fig. 5B) interacted with GDF15 in https://cn.string-db.org/ and analyzed in Cytoscape software to make beautiful protein-protein interaction network diagrams (Fig. 5C). In addition, western blot and immunohistochemical staining was used to identify our hypothesis. We found that compared to control, I/R had increased GDF15 expression from mRNA to protein level, and VB further promoted the increase of GDF15 (Fig. 5D-H). Then, we found that the therapeutic effect of VB reversing cytotoxicity and LDH activity were abolished after silencing GDF15 (Fig. 5K-L). Compared with the H/R + VB group, the expression of GPX4 in the si-GDF15 group also decrease (Fig. 5M-N), the production of SOD and GSH was decreased, and the production of MDA was elevated (Fig. 5O–Q). Furthermore, lipid peroxidation levels increased after GDF15 was silenced (Fig. S1 of supplementary file 3). At the same time, the silence of GDF15 also promoted the expression of ACSL4, and decreased the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4, which aggravated ferroptosis (Fig. 5R-U). However, ferroptosis inhibitor- Ferrostatin (Fer-1) mitigated ferroptosis aggravated by silencing GDF15 (Fig. S2 of supplementary file 3).

VB attenuates ferroptosis induced by H/R injury by upregulating GDF15. (A) The three-dimensional structure of GDF15. (B-C) Protein-protein interaction network diagrams. (D) The mRNA expression of GDF15. (D–F) The protein expression of GDF15 in 3 groups. (G-H) Representative immunohistochemical staining among the 3 groups. (I-J) Changes of GDF15 protein expression before and after transfection. (K-L) The levels of cell viability and LDH release. (M-N) Representative immunofluorescence staining of GPX4. (O-Q) The concentration of MDA, SOD and GSH in cell. (R-U) Western blots bands and histograms of ACSL4, SLC7A11 and GPX4. Data are shown as means ± SEM, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

GDF15 mitigates cold H/R-induced injury through the GPX4-mediated ferroptosis

To further explore whether GDF15 inhibits ferroptosis through upregulating GPX4, we also used recombinant GDF15 and transfected si-GPX4 to silence GPX4 expression (Fig. 6A-B). At the same time, we found that the therapeutic effect of rGDF15 reversing cytotoxicity and LDH activity were abolished after silencing GPX4 (Fig. 6C-D). Compared with the H/R + VB group, the percentage of TUNEL positive cell in the si-GPX4 group also increase (Fig. 6E-F), the production of SOD and GSH was decreased, and the production of MDA was elevated (Fig. 6G-I). At the same time, the silence of GPX4 also promoted the expression of ACSL4, and decreased the expression of SLC7A11, which aggravated ferroptosis (Fig. 6J-L). Moreover, in order to further verify the interaction between proteins, we used the AlphaFold3 website https://alphafoldserver.com/ to predict the spatial structure of the protein interaction between GDF15 and GPX4(Fig. 6M).

GDF15 attenuates ferroptosis induced by H/R injury by upregulating GPX4. (A-B) Changes of GDF15 protein expression before and after transfection. (C-D) The levels of cell viability and LDH release. (E-F) Analysis of TUNEL staining results. (D-F) The protein expression of GDF15 in 3 groups. (G-I) The concentration of MDA, SOD and GSH in cell. (J-L) Western blots bands and histograms of ACSL4 and SLC7A11. (M) Predictive structure of GDF15 and GPX4 protein interactions. Data are shown as means ± SEM, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01.

Discussion

Since Barnard’s pioneering heart transplantation in 1967, especially the improvement of modern immunosuppressive protocols, we have successfully improved the survival rate of heart transplantation to a current median survival of about 15 years20. However, I/R injury is considered of the major factor contributing to the deterioration of cardiac function following heart transplantation, much attention has been paid to identifying effective natural products for the treatment of this cardiovascular disease21. I/R injury can induce multiple forms of cell death, including apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses and autophagy. Among these, apoptosis is one of the predominant forms of cardiomyocyte death during myocardial I/R injury, primarily triggered by oxidative stress, calcium overload, inflammation and energy depletion22. During this process, the dynamic balance between oxidative and antioxidant systems is disrupted, leading to oxidative stress damage23. Additionally, damaged myocardial tissue releases numerous danger signals that activate the innate immune response, leading to the expression of multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). The activation of these receptors triggers the release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines, resulting in sterile inflammation and further tissue damage24. Autophagy is an intracellular lysosomal degradation process that plays a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by degrading and recycling cytosolic components, long-lived proteins, and organelles. Enhancing autophagic flux by reducing autophagosome accumulation during I/R injury has been shown to exert cardioprotective effects25. Previous studies have demonstrated that VB can target and inhibit NLRP3-mediated inflammation, thereby promoting neuronal functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats26. Furthermore, VB exerts neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer’s disease by blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway and mitigates intracerebral hemorrhage symptoms by modulating TLR4-mediated acute inflammatory responses27. Specially, previous research has shown that Chinese medicine possesses the potential to treat I/R injury by regulating metabolism. For example, glycyrrhizic acid exhibits promising therapeutic agent to prolong cardiac allograft survival through direct anti-inflammatory effects28. Another compound, eugenol, protects the transplanted heart against I/R injury in rats by inhibiting the inflammatory response and apoptosis29. VB has shown protection against oxidative stress, apoptosis and regulation mitochondrial dynamics in a mouse model of LPS11. Combined with the latest research at home and abroad, VB can reduce the brain and liver I/R injury30. Expect for the pathological changes of myocardial tissue, we also introduced beating score, which decreased significantly after transplantation after 8 h of ischemia. However, these markers of myocardial necrosis decreased and pathological damage of myocardial tissue was alleviated with VB treatment. In vitro, VB inhibited the ferroptosis, improved cell viability and lowered the cell percentage of TUNEL positive.

Ferroptosis is a non-apoptotic cell death caused by lipid peroxide accumulation, which is activated in cancer, neurological disease and cardiovascular disease31. Research has shown that ferroptosis plays an important role in myocardial I/R injury following heart transplantation32. Unlike apoptosis, ferroptosis is characterized by intracellular accumulation of Fe2+ and lipid peroxides leading to elevated autophagy levels, accumulation of ROS, and depletion of GSH. The large production of ROS destroys the structure and function of the cell, which in turn produces a large amount of MDA, while attracting more SOD to react and eliminate it33. Meanwhile, precent study has shown that salidroside pretreatment could alleviate ferroptosis induced by myocardial I/R through mitochondrial superoxide-dependent AMPKα2 activation34. Through our experiments, we found that VB blocked the activation of the ferroptosis induced by myocardial I/R injury through regulating indicators of the degree of oxidative stress reaction including MDA, SOD, GSH and ROS.

GPX4, known as PHGPX (phospholipid hydroperoxide-glutathione peroxidase), utilizes glutathione as a cofactor to convert lipid hydroperoxides into non-toxic lipid alcohols to regulate ferroptosis, which inhibits proteins found in liposomes and biofilms35. There are studies demonstrated that both GPX4 inhibitors and GPX4-specific siRNA (si-GPX4) result in reduced solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) expression36. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) is also an important regulator of ferroptosis, which can be developed as a biomarker for disease diagnosis. Previous study indicated that epigallocatechin gallate attenuated acute myocardial infarction by inhibiting ferroptosis via miR-450b-5p/ACSL4 axis37. SLC7A11 is a key component of cystine/glutamate antiporter, which is to enhance glutathione production and promote GPX4-mediated ferroptosis38 More studies have shown that Ginsenoside Re attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced ferroptosis via miR-144-3p/SLC7A1139. In our study, when myocardial I/R occurred, the levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11 decreased, but the level of ACSL4 increased, which lead to an activation in lipid peroxidation production, ultimately inducing ferroptosis. However, VB can attenuate the I/R-induced changes in the above ferroptosis-related proteins.

When cardiomyocytes undergo I/R injury, necrosis and oxidative stress, the level of GDF15 is elevated, which plays a protective role of inhibiting inflammation, stabilizing plaque formation, and preventing cardiac remodeling40,41,42. GDF15 has been shown to inactivate NF-κB signaling for preventing alloimmune rejection in heart transplantation43 and protect against cold I/R injury in heart transplantation through the Foxo3a signaling pathway44. In this study, we found that GDF15 level among VB-treated mice was significantly higher than for untreated transplanted mice. Earlier research has already shown that Shexiang Baoxin Pill increased GDF15 expression in rats with acute myocardial infarction45, and empaglifozin raised plasma GDF15 levels in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction46.In our study, VB enhances the accumulation of GDF15 that resilience to I/R injury.

Previous studies indicated that GDF15 effectively alleviated neuronal ferroptosis post spinal cord injury via the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway and promoted locomotor recovery of spinal cord injury mice47. There are studies shown that GDF15 was related with the occurrence of ferroptosis by bioinformatics analysis and was elevated in renal I/R injury group48. Moreover, GDF15 could alleviate ferroptosis-related functional mechanism by increasing the expression of GPX4 in the process of myocardial I/R injury49. However, our study presents several novel findings: Firstly, we utilized a heart transplantation model, whereas prior studies primarily focused on the myocardial infarction-reperfusion model. In addition, we identified that GDF15 regulates ferroptosis through the GPX4/SLC7A11 axis. Furthermore, we conducted an in-depth mechanistic investigation using siRNA-mediated GPX4 knockdown and AlphaFold3-based molecular interaction modeling. Of course, some studies have found that exogenous drugs can inhibit the occurrence of ferroptosis by up-regulating the expression of GDF15, for example, exogenous melatonin ameliorates steroid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head by modulating ferroptosis through GDF15-mediated signaling50. Our results are consistent with these studies, when GDF15 is silenced, the protective effect of VB is not completely nullified. At the same time, rGDF15 treatment further promotes the expression of GPX4. Finally, we also silenced GPX4 on the basis of rGDF15 to explore the relationship between GDF15 and GPX4, which found that the effective effect of GDF15 in inhibiting oxidative stress, apoptosis and ferroptosis was mitigated while interferencing the expression of GPX4.

Conclusions

In summary, we identified a novel mechanism by which VB inhibited GPX4-mediated ferroptosis against myocardial I/R injury through upregulating GDF15, and the detailed mechanism diagram is shown in Fig. 7. Our research offered a new method for explaining VB resistance to myocardial I/R injury following heart transplantation and a fresh outlook on I/R prevention and treatment. However, our study also has certain limitations. It is regrettable whether GDF15 directly acts on which target of GPX4 protein is not known. In addition, whether there is a difference in mechanism between cold I/R injury in heart transplantation and reperfusion injury after myocardial infarction. We will continue to explore the relationship between GDF15 and GPX4 by immunoprecipitation in the following experiments.

Materials and methods

Experimental animal and groups

C57BL/6J mice (6-8weeks) were purchased from Hunan An Sheng Mei Pharmaceutical Research Institute Co.,Ltd (Hunan, China) and were housed in the Animal Experiment Center of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, and care of the animals was in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal treatment.

Heterotopic heart transplantation was performed using a modified non-suture cuff technique51 (heterotopic heart transplantation.mp4 of supplementary video). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). The donor was given heparin (1000 U/kg) and induced cardiac arrest by the injection of ice-cold, high-potassium cardioplegia solution into the aortic root. The mice were transplanted immediately as control group, or stored in the same UW solution for 8 h according to the I/R groups52. The donor heart was heterotrophically transplanted to the neck vessels of the recipient, and the reperfusion continued for 24 h after the opening of blood flow. VB was purchased from Aladdin Chemistry Co., Ltd (61276-17-3) and intraperitoneally injected at 20 mg/kg 3 days before surgery52.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

The donor heart was isolated from the receptor’s neck 24 h after reperfusion and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline. Then, the cardiac tissues were fixed with 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. These tissues were subsequently sectioned into 4–6 μm slices, dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated with graded alcohol, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) according to the standard protocol. The morphological structure of each sample was examined under a light microscope, and photomicrographs were taken at magnification (Olympus IX51, Japan).

Beating score

Beating score of heart grafts was assessed visually after 24 h of reperfusion using the Stanford cardiac surgery laboratory graft scoring system (0: No contraction, 1: Contraction barely visible or palpable, 2: Obvious decrease in contraction strength, but still contracting in a coordinated manner, 3: Strong coordinated beating but noticeable decrease in strength or rate, 4: Strong contraction of both ventricles, regular rate).

Transmission electron microscopy

After surgery, 1 mm3 of tissues from the left ventricles of mice hearts were excised and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 24 h. The tissue samples were then washed, fixed, dehydrated, embedded, cured with a buffer solution, and then cut into ultrathin sections using an ultra-thin microtome. The micrographs of these ultrathin sections were detected with TEM (HT7700, Japan) under the guidance of professional teachers at the Electron Microscopy Center of the People’s Hospital of Wuhan University.

Cell culture and treatment protocol

H9c2 rat heart cell line was purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China, Cat Number: GNR 5) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Pricella Laboratories, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco Laboratories, USA) and 100 U/ml penicillin/100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco Laboratories, USA) in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C as described previously53.

A vitro hypothermal H/R model was used. H9c2 cells were cultured in 6-well plates or 96-well microplates with DMEM 24 h before hypoxia. Cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) once, then 2mL of UW was added onto the cells and were placed in the three-gas incubator (Don Whitley Scientific, Shipley, UK) set at 10 °C, 0.5% O2, 4.0% CO2, and 95.5% N2 for 18 h. Next, cells removed from the primary incubator and complete DMEM medium was added to each well incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95%N2. Cells in the control group were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% air54. The VB were given before hypoxia for 24 h.

For RNA interference, the siRNA sequences used to silence GDF15, GPX4 or control scramble siRNA were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 for 6 h in Opti-MEM medium. Next, cells were transferred to full-growth medium for another 24 h and processed as group divided, protein level detect the transfection efficiency for further studies. Recombinant GDF15 (rGDF5; Abcam, Cambridge) was used to provide exogenetic expression of GDF15 in vitro.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by using a CCK-8 assay kit (Jian Cheng, Nanjing, China) in 96-well plates according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance was determined at 450 nm using a PerkinElmer microplate reader (PerkinElmer VICTOR 1420, USA).

Measurement of MAD, SOD, GSH, CK-MB, cTnI and LDH levels

At the end of reperfusion and reoxygenation, mice’s serum, myocardial samples and medium were collected. Kits for detecting SOD activities, MDA and LDH content were purchased from the Institute of Nanjing Jian Cheng BioEngineering. Kits for detecting CK-MB, cTnI and GSH content were purchased from the Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. These myocardial biomarkers were detected with an automated analyzer (Chemray 240/800, Shenzhen, China).

RNA extraction and quantitative Real-time PCR (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the myocardial samples and cell using Trizol reagent. Two micrograms of RNA from each sample were then reversed transcribed into cDNA according to the Prime-Script RT reagent kit instruction (Servicebio, Hubei, China). The RT-PCR was performed using a SYBR Green qPCR Reagent Kit (Servicebio, Hubei, China). The used primers are listed in Tables. The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA level and analyzed by using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

Western blot and band quantitation

After treated with different stimulus, cardiac tissues and cells were lysed in ice-cold radio immunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) for 20 min, and then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min to obtain supernatants. A Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to measure the concentration of proteins. Equal amount of protein lysates was loaded into a 5-15% SDS-PAGE geland transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Next, the membranes were incubated in protein free rapid blocking buffer (Epizyme Biomedical Technology, Shanghai, China). Primary antibodies were incubated with the membranes overnight at 4 °C, including β-actin (1:1000, GB15001, Servicebio), GDF15(1:5000, 27455-1-AP, proteinntech), Bax (1:2000, A20227, ABclonal), Bcl-2 (1:1000, A20777, ABclonal), cleaved-caspase-3 (1:1000, A22869, ABclonal), GPX4 (1:5000, A25009, ABclonal), ACSL4 (1:100000, A20414, ABclonal), SLC7A11 (1:1000, A13685, ABclonal). After 3 cycles of 10-minute washing in TBS/0.1% Tween-20 (0.1% TBST), the membranes were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibody (1:5000, SA00001-2, SA00001-1, Proteintech) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the membranes were washed again with TBST for 3 times, 5 min of each time. The biological image analysis system was used for the final analysis (Bio-Rad, USA). The original, unprocessed versions have been cited in “supplementary file 1”. Each sample’s β-actin levels were used to determine the relative expression levels of the target proteins.

TUNEL staining

The cell injury was quantified in slices dripped with permeabilizing cell rupture fluid permeabilization solution Triton X-100 (Servicebio, Hubei, China) using the TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were counterstained with a DAPI staining solution (Servicebio, Wuhan, China) for 10 min at room temperature, and the TUNEL signal was observed under fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). The percentage of TUNEL positive cell was determined using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA).

Measurement of ROS generation

Intracellular ROS level was assayed by the fluorescent probe dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) (Sigma, USA). After the introduction of different stimulus, cells were incubated with 50 µM DCFH-DA at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark. Then, the cells were washed twice using cold PBS. The fluorescence images of intracellular ROS were acquired by using fluorescence microscopy (Olympus IX51, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry staining

Dewaxed paraffin sections were placed in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated for antigen repair. The tissues were incubated at 4 ℃ overnight with the GDF15(1: 200, 27455-1-AP, proteintech) and GPX4(1:500, A25009, ABclonal) primary antibody. After 40 min of incubation with the secondary antibody (1:100, AS-1109, Aspen, Californian, USA) at 37 ℃ in the dark, the myocardial tissues were stained with DAPI for 20–30 min at room temperature in the dark. Four non-overlapping fields of view in the peri-infarct region of each mouse (n = 6 per group) were randomly selected under a microscope. The magnification light microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used to take images at ×200 fields.

Immunofluorescence staining

The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and bathed with PBS. 0.5% Triton X-100 was added to the medium at room temperature for 10 min. The cells were blocked with goat serum for 30 min and then incubated with mixture of anti-GPX4 (1:200, A25009, ABclonal) antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After the cells were washed by PBS, the excess liquid was sucked up by absorbent paper and the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) at 37 ℃ for 1 h. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (Servicebio, Hubei, China) for 5 min. Photographs were taken under a confocal or fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). The intensities of target proteins were measured by ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All results were analyzed using Graphpad Prism 9.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA) and presented as means ± standard deviation. All the data we used were normally distributed. A two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was conducted to compare two experimental groups or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). p-values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Du, Y. et al. Heart transplantation: A bibliometric review from 1990–2021. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 47, 101176 (2022).

Reichart, B. et al. Cardiac xenotransplantation: from concept to clinic. Cardiovasc. Res. 118, 3499–3516 (2023).

Jernryd, V., Metzsch, C., Andersson, B. & Nilsson, J. The influence of ischemia and reperfusion time on outcome in heart transplantation. Clin. Transpl. 34, e13840 (2020).

Awad, M. A., Shah, A. & Griffith, B. P. Current status and outcomes in heart transplantation: A narrative review. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 23, 11 (2022).

Ledwoch, N. et al. Identification of distinct secretory patterns and their regulatory networks of ischemia versus reperfusion phases in clinical heart transplantation. Cytokine 149, 155744 (2022).

Lund, L. H. et al. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: Thirty-Fourth adult heart transplantation Report-2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 36, 1037–1046 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Resveratrol inhibits autophagy against myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion injury through the DJ-1/MEKK1/JNK pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 951, 175748 (2023).

Qin, G. W., Lu, P., Peng, L. & Jiang, W. Ginsenoside Rb1 inhibits cardiomyocyte autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am. J. Chin. Med. 49, 1913–1927 (2021).

Xiao, Y., Ren, Q. & Wu, L. The Pharmacokinetic property and Pharmacological activity of acteoside: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 153, 113296 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. The Neuroprotection of Verbascoside in Alzheimer’s Disease Mediated through Mitigation of Neuroinflammation via Blocking NF-kappaB-p65 Signaling. Nutrients. 14, (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Verbascoside protects from LPS-induced septic cardiomyopathy via alleviating cardiac inflammation, oxidative stress and regulating mitochondrial dynamics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 233, 113327 (2022).

Siddiqui, J. A. et al. Pathophysiological role of growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) in obesity, cancer, and Cachexia. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 64, 71–83 (2022).

Johann, K., Kleinert, M. & Klaus, S. The Role of GDF15 as a Myomitokine. Cells. 10 (2021).

Ferreira, J. P. et al. Growth differentiation Factor-15 and the effect of empagliflozin in heart failure: findings from the EMPEROR program. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 26, 155–164 (2024).

Cai, W. et al. Alox15/15-HpETE aggravates myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte ferroptosis. Circulation 147, 1444–1460 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. International consensus guidelines for the definition, detection, and interpretation of Autophagy-Dependent ferroptosis. Autophagy 20, 1213–1246 (2024).

Zhang, M. et al. Ischemia-Reperfusion injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 12 (2024).

Shu, G. et al. Galangin alleviated Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting ferroptosis through GSTP1/JNK pathway. Phytomedicine 134, 155989 (2024).

Shi, H. et al. GSDMD-Mediated cardiomyocyte pyroptosis promotes myocardial I/R injury. Circ. Res. 129, 383–396 (2021).

Stehlik, J., Kobashigawa, J., Hunt, S. A., Reichenspurner, H. & Kirklin, J. K. Honoring 50 years of clinical heart transplantation in circulation: In-Depth State-of-the-Art review. Circulation 137, 71–87 (2018).

Wu, Z. et al. Prompt Graft Cooling Enhances Cardioprotection during Heart Transplantation Procedures through the Regulation of Mitophagy. Cells. 10, (2021).

Li, J. et al. Preconditioning with acteoside ameliorates myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion injury by targeting HSP90AA1 and the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 31, (2025).

Xiang, M. et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in Reperfusion following Myocardial Ischemia and its Treatments. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 6614009 (2021). (2021).

Shen, S. et al. Single-Cell RNA sequencing reveals S100a9(hi) macrophages promote the transition from acute inflammation to fibrotic remodeling after myocardial Ischemia–Reperfusion. Theranostics 14, 1241–1259 (2024).

Gu, S. et al. Downregulation of LAPTM4B contributes to the impairment of the autophagic flux via unopposed activation of mTORC1 signaling during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 127, e148–e165 (2020).

Zhou, H., Zhang, C. & Huang, C. Verbascoside attenuates acute inflammatory injury caused by an intracerebral hemorrhage through the suppression of NLRP3. Neurochem Res. 46, 770–777 (2021).

Lai, X. et al. Verbascoside attenuates acute inflammatory injury in experimental cerebral hemorrhage by suppressing TLR4. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 519, 721–726 (2019).

Yamamoto, Y. et al. Effects of glycyrrhizic acid in licorice on prolongation of murine cardiac allograft survival. Transpl. Proc. 54, 476–481 (2022).

Feng, W. et al. Eugenol protects the transplanted heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats by inhibiting the inflammatory response and apoptosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 16, 3464–3470 (2018).

Zhao, Y., Wang, S., Pan, J. & Ma, K. Verbascoside: A neuroprotective phenylethanoid glycosides with Anti-Depressive properties. Phytomedicine 120, 155027 (2023).

Pope, L. E. & Dixon, S. J. Regulation of ferroptosis by lipid metabolism. Trends Cell. Biol. 33, 1077–1087 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. Ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 170, 116057 (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. The pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic drugs for myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine 129, 155649 (2024).

Yang, B. et al. Salidroside pretreatment alleviates ferroptosis induced by myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through mitochondrial Superoxide-Dependent AMPKalpha2 activation. Phytomedicine 128, 155365 (2024).

Bi, Y. et al. FUNDC1 interacts with GPx4 to govern hepatic ferroptosis and fibrotic injury through a Mitophagy-Dependent manner. J. Adv. Res. 55, 45–60 (2024).

Li, Z., Cui, C., Xu, L., Ding, M. & Wang, Y. Metformin suppresses metabolic Dysfunction-Associated fatty liver disease by ferroptosis and apoptosis via activation of oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 58, 686–701 (2024).

Yu, Q. et al. EGCG attenuated acute myocardial infarction by inhibiting ferroptosis via miR-450b-5p/ACSL4 Axis. Phytomedicine 119, 154999 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Koppula, P. & Gan, B. Regulation of H2A ubiquitination and SLC7A11 expression by BAP1 and PRC1. Cell. Cycle. 18, 773–783 (2019).

Ye, J. et al. Ginsenoside re attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion induced ferroptosis via miR-144-3p/SLC7A11. Phytomedicine 113, 154681 (2023).

Buendgens, L. et al. Growth Differentiation Factor-15 is a Predictor of Mortality in Critically Ill Patients with Sepsis. Dis. Markers. 5271203 (2017). (2017).

Baek, S. J. & Eling, T. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15): A survival protein with therapeutic potential in metabolic diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 198, 46–58 (2019).

Desmedt, S. et al. Growth differentiation factor 15: A novel biomarker with high clinical potential. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 56, 333–350 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. GDF15 regulates Malat-1 circular RNA and inactivates NFkappaB signaling leading to immune tolerogenic DCs for preventing alloimmune rejection in heart transplantation. Front. Immunol. 9, 2407 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Over-Expression of growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) preventing cold ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury in heart transplantation through Foxo3a signaling. Oncotarget 8, 36531–36544 (2017).

Wei, B. Y. et al. Shexiang Baoxin pill treats acute myocardial infarction by promoting angiogenesis via GDF15-TRPV4 signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 165, 115186 (2023).

Omar, M. et al. The effect of empagliflozin on growth differentiation factor 15 in patients with heart failure: A randomized controlled trial (Empire HF Biomarker). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 34 (2022).

Xia, M. et al. Growth differentiation factor 15 regulates oxidative Stress-Dependent ferroptosis post spinal cord injury by stabilizing the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 905115 (2022).

Chen, R. Y. et al. Gene signature and prediction model of the Mitophagy-Associated immune microenvironment in renal Ischemia-Reperfusion injury. Front. Immunol. 14, 1117297 (2023).

Gao, Q. et al. GDF15 restrains myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion injury through inhibiting GPX4 mediated ferroptosis. Aging (Albany NY). 16, 617–626 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Exogenous melatonin ameliorates Steroid-Induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head by modulating ferroptosis through GDF15-mediated signaling. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 14, 171 (2023).

Fei, Q. et al. Mst1 attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury following heterotopic heart transplantation in mice through regulating Keap1/Nrf2 Axis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 644, 140–148 (2023).

Zhou, L. et al. MicroRNA and mRNA signatures in ischemia reperfusion injury in heart transplantation. PLoS One. 8, e79805 (2013).

Liu, T. et al. HSP70 protects H9C2 cells from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury through STIM1/IP3R. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 27, 535–544 (2022).

Zheng, H. et al. An addition of U0126 protecting heart grafts from prolonged cold Ischemia-Reperfusion injury in heart transplantation: A new preservation strategy. Transplantation 105, 308–317 (2021).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172160, 82372188 and 82202408), Hubei Province Science and Technology Department Key Research and Development Plan (Grant No.2022BCE007) and Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 2023AFB821).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. Z. and Z. Q. conceived the present study and prepared the manuscript. Y. Z.and J.Z. performed most of experiments. Z. Q. and S. L. analyzed the results. Q.H. ,T.H. and J. Z. provided technical support. Z.X., R. X. and Q. S. provided funding support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All experimental protocols were approved by the Medical Faculty Ethics Committee of Wuhan University (Permit Number:20230411B). The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Zhan, J., Qiu, Z. et al. Verbascoside attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced ferroptosis following heterotopic heart transplantation via modulating GDF15/GPX4/SLC7A11 pathway. Sci Rep 15, 15651 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00112-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00112-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The interaction between ferroptosis and myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)