Abstract

It has been suggested that the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet as a plant-based dietary pattern can be useful in improvement of risk factors of metabolic syndrome (MetS). We designed a study to evaluate the effect of the DASH diet on insulin resistance and lipid accumulation product (LAP) in subjects with MetS. 60 subjects with MetS were assigned into two groups including the intervention group and the control group. The intervention group received DASH diet and the control group received a common healthy diet for 12 weeks. We measured fasting plasma glucose (FPG), triglyceride and glucose (TyG) index, metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR) and LAP before and after intervention. We utilized SPSS software version 24 and an intention-to-treat method for data analysis. A total of 59 subjects completed the trial. After intervention a significant difference was observed between groups in FPG (P < 0.001), TyG index (P < 0.001) and LAP (P = 0.01). However, there was no significant difference between groups in values of METS-IR (P = 0.27). There was a significant reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group in FPG (-7.86 ± 10.08 vs. 0.97 ± 15.51; P = 0.01), TyG index (-0.20 ± 0.14 vs. 0.02 ± 0.11; P < 0.001), METS-IR (-2.50 ± 1.99 vs. -0.53 ± 2.21; P = 0.001) and LAP (-20.06 ± 12.02 vs. -5.87 ± 15.17; P < 0.001). Adherence to DASH diet can reduce some cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with MetS. Further clinical trials are required to reach a firm conclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of metabolic dysregulations that contribute to the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases1,2. It has been estimated that 20%−35% of adults suffer from MetS3,4. Insulin resistance, which is known as a reduced ability of insulin to stimulate glucose utilization, is involved in the development of MetS as well as the progression of its related complications through various mechanisms5,6. In addition, visceral obesity as a key criterion in diagnosis of MetS is one of the main risk factors for non-communicable diseases7,8. Lipid accumulation product (LAP) is a valid tool to evaluate the cardiovascular risk and accumulation of fat9,10. It is based on waist circumference (WC) and triglyceride (TG), and is a better predictor than WC or TG alone in assessing the risk of complications related to obesity and dyslipidemia11,12. It has been confirmed that following unhealthy dietary patterns and sedentary lifestyle are the important modifiable risk factors of MetS13.

The dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet is a plant-based dietary pattern with limited amounts of saturated fat, cholesterol, red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as sodium, and provides high amounts of whole grains, vegetables, fruits, low-fat dairy products, legumes, and nuts14. It has been reported that following DASH diet can be useful in the management of cardiometabolic risk factors including dyslipidemia, hypertension and obesity15,16,17,18. There are limited number of studies investigating the effects of DASH diet in subjects with MetS19,20. Only Saneei et al.20 assessed the effect of recommendations to follow the DASH diet on childhood metabolic syndrome. To date, no clinical trial has evaluated the effect of adherence to DASH diet on LAP. The present study was designed to determine the effect of DASH diet on insulin resistance and LAP in subjects with MetS. It has been hypothesized DASH diet can improve insulin resistance and LAP in subjects with MetS.

Methods

Participants

The present study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The subjects were recruited from October 2022 to November 2022 in Diabetes Research Center, Yazd, Iran. The inclusion criteria were: age between 30 and 60 years and diagnosis of MetS according to International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria21. The exclusion criteria were hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, Wilson disease, kidney diseases, history of hepatitis, hemochromatosis, bariatric surgery, pregnancy and lactation, and consuming calcium channel blockers, synthetic estrogens, vitamin D, vitamin E, and omega-3.

Trial design

We conducted a RCT to evaluate the effect of DASH diet on insulin resistance and LAP in subjects with MetS. Before the beginning of the study the participants signed a written informed consent approved by the ethical committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran (IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1401.016). We conducted this study in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. We registered the study protocol on 21 October 2022 at the website of Iranian clinical trials (IRCT20180201038585 N12; URL: https://irct.behdasht.gov.ir/trial/66161). Opaque sealed envelopes were used to perform allocation concealment. The subjects were randomly divided into two groups including the intervention and the control groups. A stratified randomization method considering gender (male/female) and age (30–45 and 45–60 years) was used and the subjects were divided into groups utilizing a computer-generated random numbers table22.

Intervention

The intervention group followed an energy-restricted DASH diet containing 50–55% carbohydrate, 15–20% protein, and 30% total fat. The DASH diet had high amounts of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat dairy products, and low amounts of saturated fats, cholesterol, refined grains, and sugar-sweetened beverages. This diet is rich in fiber and micronutrients especially potassium, magnesium, vitamin C, vitamin A and folate. The servings of meats, fats and oils are low in DASH diet. The control group received an energy-restricted diet with 50–55% carbohydrate, 15–20% protein, and 30% total fat. The control diet was a healthy common dietary pattern with a balanced amount of food groups. The control diet had lower amounts of fiber and micronutrients compared to the DASH diet. In general, we adjusted the effects of energy restriction and macronutrient ratio to achieve the beneficial effects of DASH diet more clearly compared to a common healthy diet. The energy requirement of each subject was calculated based on the Harris-Benedict equation23. The subjects with body mass index (BMI) between 25–31 kg/m2 received 500 kcal lower than their total energy requirement and subjects with BMI higher than 31 kg/m2 received 700 kcal lower than their total energy requirement. The dietary intakes of subjects were checked every 4 weeks via phone interviews.

Dietary intake and physical activity assessment

Assessment of dietary intake and physical activity was done at the baseline and the end of the intervention using a 3-day (1 weekend day and 2 nonconsecutive weekdays) food record9 and a metabolic equivalent of task (MET) questionnaire24,25, respectively.

In addition, we used Nutritionist IV (N-Squared Computing, Salem, OR, USA) modified for Iranian foods was used to analyze the dietary intakes.

Anthropometric assessment

Assessment of weight was done by a digital Seca scale (Seca, Germany). We measured the height of subjects utilizing a stadiometer (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). The BMI was calculated based on the following formula: weight (kg)/height squared (m2).

Laboratory evaluations

After 10 h fasting, 10 cc blood was drawn and serum samples were stored at −70° C. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), TG and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) were measured at the baseline and the end of the study via Pars Azmoon kits (made in Iran) utilizing an autoanalyzer (AVIDA 1800 chemistry system; Siemens, United Kingdom).

Insulin resistance and LAP calculation.

Calculation of insulin resistance indices including triglyceride and glucose (TyG) index26 and metabolic score for insulin resistance (METS-IR)27 was done based on the following equations:

LAP was calculated using following formula (10):

Sample size

The present article is a part of our main project that estimated the optimal sample size (30 subjects in each group) based on the values of WC in the study of Razavi Zade et al.17, 95% confidence interval, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2. We conducted a retrospective power analysis for outcomes of this article to assure the sample size is adequate to detect statistical significance, and adequate power was observed.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS software version 24 and an intention-to-treat method to analyze the data. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was utilized to evaluate the normality of variables. An independent t-test (for continuous variables) and chi-square test (for categorical variables) were used to compare the differences between groups. Paired t-test was utilized to compare the variables before and after the intervention in each group. Adjustment of confounding factors was performed by Univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). P value equal to or less than 0.05 was significant.

Results

Characteristics of subjects

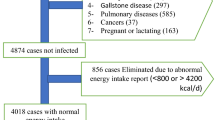

A total of 59 subjects (30 subjects in the intervention group and 29 subjects in the control group) completed the trial. One subject was excluded from study due to non-referral (Fig. 1). No significant difference was found between groups in age, gender distribution, smoking, education, physical activity and height (Table 1). There was no adverse event related to the intervention during the study.

Dietary intakes

Table 2 shows the dietary intakes of subjects. At the baseline, there was no significant difference between the intervention group and the control group in energy and dietary intakes, except for grains and dairy products. Compared to the control group, the intake of grains was higher (P < 0.001) and intake of dairy products was lower (P = 0.02) in the intervention group. After intervention, no significant difference was observed between the intervention group and the control group in energy and macronutrients intake and also consumption of sodium, simple sugars and grains (P > 0.05). In comparison to the control group, the intake of potassium, vitamin C, vitamin A, folate, fiber, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds and legumes, and dairy products was higher (P < 0.001) and servings of meats, fats and oils was lower (P < 0.001) in the intervention group. In addition, the intervention group consumed higher amounts of magnesium (P = 0.006).

Outcomes

We found a significant difference between groups in baseline values of FPG (P = 0.03) and TyG index (P = 0.02). However, no significant difference was observed between groups in baseline values of METS-IR (P = 0.82) and LAP (P = 0.40) (Table 3).

After intervention a significant difference was found between groups in FPG (P < 0.001), TyG index (P < 0.001) and LAP (P = 0.01). However, there was no significant difference between groups in values of METS-IR (P = 0.27). We found a significant reduction in the intervention group compared to the control group in FPG (−7.86 ± 10.08 vs. 0.97 ± 15.51; P = 0.01), TyG index (−0.20 ± 0.14 vs. 0.02 ± 0.11; P < 0.001), METS-IR (−2.50 ± 1.99 vs. −0.53 ± 2.21; P = 0.001) and LAP (−20.06 ± 12.02 vs. −5.87 ± 15.17; P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Discussion

We reported that 12-week adherence to DASH diet can improve some cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with MetS.

Calorie restriction and weight loss are important factors in improving glycemic control28. In the present study, both the intervention and control groups followed a calorie-restricted diet to control the effect of energy intake on the outcomes of the study. However, we demonstrated in our previous study that the weight loss in the intervention group following the DASH diet was significantly higher than the control group29. This weight loss independent of calorie restriction can be due to the higher consumption of healthy food groups in the intervention group.

Whole grains, fruits, and vegetables are the main sources of fiber30. Fiber by increasing the abundance of health-promoting bacteria and increasing production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) including acetate, propionate, and butyrate can trigger the clearance of lipids from the liver, increase glucagon levels, regulate glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and GLP-2 secretion and improve insulin sensitivity28,31,32,33.

Some studies have evaluated the effect of DASH diet on insulin resistance. A study that was conducted among patients with gestational diabetes mellitus reported a significant improvement in FPG, insulin and homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) after 4-week adherence to DASH diet34. Another clinical trial demonstrated that following DASH diet for 8 weeks reduced the levels of insulin and HOMA-IR in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome35. Moreover, it has been reported that following DASH diet resulted for 8 weeks decreased levels of insulin and HOMA-IR in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease17. It has been found that recommendation to follow DASH diet for 6 weeks resulted in a significant decrease in serum insulin levels and a non-significant reduction in the HOMA-IR score20. However, a clinical trial that was conducted among healthy subjects showed that adherence to DASH diet has no effect on glucose and insulin levels36. It seems health status is an important factor in this field. Probably, following the DASH diet has beneficial effects on insulin resistance in people with various diseases, but not in healthy people.

The present study was the first clinical trial investigating the effect of adherence to DASH diet on LAP. LAP as a new available tool for estimating cardiovascular risk is based on WC and TG10. In consistence with our result, a study indicated that 6-month adherence to DASH diet can decrease TG16. In addition, a recent meta-analysis revealed that adherence to DASH diet can decrease TG15. On the other hand, it has been found that following DASH diet for 12 weeks decreased body fat mass in subjects with obesity37. Moreover, a study reported a significant reduction of BMI in adults after 12-week adherence to DASH diet38. However, according to the findings of Saneei et al.20, following DASH diet for 6 weeks has no effect on WC and TG in adolescents with MetS. In general, longer intervention duration had more beneficial effects.

One of the important factors in reducing fat accumulation is calorie restriction and consequently weight loss39,40. Our previous study showed that after controlling for caloric intake, reduction of weight and WC in the intervention group following the DASH diet was significantly higher than the control group, which could indicate the beneficial effects of consuming healthy food groups in higher amounts in the intervention group compared to the control group29. DASH diet by providing high amounts of fiber and polyphenols can reduce TG, decrease lipid peroxidation, reduce hepatic levels of cholesterol, mediate lipogenesis and β-oxidation in the liver, attenuate intrahepatic production of lipids and also increase cholesterol excretion41,42,43,44,45. Fiber can also decrease appetite, reduce macronutrients absorption and improve the sense of satiety41. In addition, whole grains can decrease hepatic fat accumulation46,

The present study was a part of our main project. We previously reported the findings related to the effect of DASH diet on fatty liver and cardiovascular risk factors29. To follow the ethical principals in research, we declare that we used the same data for the present article. To proper understanding and interpretation, Fig. 1 and some important information (baseline characteristics, dietary intakes and physical activity) of our previous article were added to the present article.

The present study has some strengths. For the first time, we evaluated the effect of DASH diet on LAP in subjects with MetS. In addition, we used new indices with appropriate accuracy to estimate insulin resistance. We checked the adherence of subjects to intervention every two weeks. However, the study has some limitations. The study limitations include relatively short follow-up and the lack of investigation of the effects of intervention on the main results in the middle of the intervention period (week 6).

Conclusions

The present study provides some evidence that DASH diet can improve some cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with MetS. Since DASH diet is safe and appropriate for long-term use, it can be an ideal therapeutic approach in management of risk factors of MetS. Further studies must be conducted in this field to reach a firm conclusion.

Data availability

The data and materials of the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, X. & Lerman, L. O. The metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Transl. Res. 183, 14–25 (2017).

Tune, J. D., Goodwill, A. G., Sassoon, D. J. & Mather, K. J. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl. Res. 183, 57–70 (2017).

Saklayen, M. G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 20, 12 (2018).

Kalan Farmanfarma, K. et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iran: A meta-analysis of 69 studies. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 13(1), 792–799 (2019).

Manco, M. Insulin resistance and nafld: A dangerous liaison beyond the genetics. Children 4(8), 74 (2017).

Lann, D., Gallagher, E. & Leroith, D. Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Minerva Med. 99(3), 253–262 (2008).

Yu, S. J. et al. Visceral obesity predicts significant fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med. (United States). 94(48), e2159 (2015).

van der Poorten, D. et al. Visceral fat: A key mediator of steatohepatitis in metabolic liver disease. Hepatology 48(2), 449–457 (2008).

Sangouni, A. A. et al. Effect of Cornus mas L. fruit extract on lipid accumulation product and cardiovascular indices in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 47, 51–57 (2022).

Bedogni, G., Kahn, H. S., Bellentani, S. & Tiribelli, C. A simple index of lipid overaccumulation is a good marker of liver steatosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 10, 98 (2010).

Sangouni, A. A., Sasanfar, B., Ghadiri-Anari, A. & Hosseinzadeh, M. Effect of L-carnitine supplementation on liver fat content and cardiometabolic indices in overweight/obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 46, 54–59 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Body adiposity index, lipid accumulation product, and cardiometabolic index reveal the contribution of adiposity phenotypes in the risk of hyperuricemia among Chinese rural population. Clin. Rheumatol. 37(8), 2221–2231 (2018).

Dobrowolski, P. et al. Metabolic syndrome a new definition and management guidelines. Arch. Med. Sci. 18(5), 1133–1156 (2022).

Campbell, A. P. DASH eating plan: An eating pattern for diabetes management. Diabetes Spectr. 30(2), 76–81 (2017).

Guo, R. et al. Effects of the modified DASH diet on adults with elevated blood pressure or hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 8, 725020 (2021).

Lima, S. T. R. M. et al. Reductions in glycemic and lipid profiles in hypertensive patients undergoing the Brazilian dietary approach to break hypertension: A randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Res. 34(8), 682–687 (2014).

Razavi Zade, M. et al. The effects of DASH diet on weight loss and metabolic status in adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized clinical trial. Liver Int. 36(4), 563–571 (2016).

Lari, A. et al. The effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on metabolic risk factors in patients with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 31(10), 2766–2778 (2021).

Azadbakht, L., Mirmiran, P., Esmaillzadeh, A., Azizi, T. & Azizi, F. Beneficial effects of a dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 28(12), 2823–2831 (2005).

Saneei, P. et al. Effects of recommendations to follow the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet v. usual dietary advice on childhood metabolic syndrome: A randomised cross-over clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 110(12), 2250–2259 (2013).

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. The metabolic syndrome - A new worldwide definition. Lancet 366(9491), 1059–1062 (2005).

Saghaei, M. Random allocation software for parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 4, 26 (2004).

Luy, S. C. R. & Dampil, O. A. Comparison of the harris-benedict equation, bioelectrical impedance analysis, and indirect calorimetry for measurement of basal metabolic rate among adult obese filipino patients with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 33(2), 152–159 (2018).

Aadahl, M. & Jørgensen, T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 35(7), 1196–1202 (2003).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32(9 Suppl), S498-504 (2000).

Simental-Mendía, L. E., Rodríguez-Morán, M. & Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6(4), 299–304 (2008).

Bello-Chavolla, O. Y. et al. METS-IR, a novel score to evaluate insulin sensitivity, is predictive of visceral adiposity and incident type 2 diabetes. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 178(5), 533–544 (2018).

Muscogiuri, G. et al. Nutritional guidelines for the management of insulin resistance. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62(25), 6947–6960 (2022).

Sangouni, A. A., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Parastouei, K. The effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet on fatty liver and cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Endocr. Disord. 24(1), 126 (2024).

Fardet, A. New hypotheses for the health-protective mechanisms of whole-grain cereals: What is beyond fibre?. Nutr. Res. Rev. 23(1), 65–134 (2010).

Den Besten, G. et al. Short-chain fatty acids protect against high-fat diet-induced obesity via a pparg-dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes 64(7), 2398–2408 (2015).

Mollica, M. P. et al. Butyrate regulates liver mitochondrial function, efficiency, and dynamics in insulin-resistant obese mice. Diabetes 66(5), 1405–1418 (2017).

Canfora, E. E., Jocken, J. W. & Blaak, E. E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 11(10), 577–591 (2015).

Asemi, Z. et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the effect of DASH diet on insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes. Nutrition 29(4), 619–624 (2013).

Asemi, Z. & Esmaillzadeh, A. DASH diet, insulin resistance, and serum hs-CRP in polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Horm. Metab. Res. 47(3), 232–238 (2015).

Hodson, L., Harnden, K. E., Roberts, R., Dennis, A. L. & Frayn, K. N. Does the DASH diet lower blood pressure by altering peripheral vascular function. J. Hum. Hypertens. 24(5), 312–319 (2010).

Perry, C. A., Van, G. G. P., Kauffman, A. & Hossain, M. a calorie-restricted DASH diet reduces body fat and maintains muscle strength in obese older adults. Nutrients 12, 102 (2020).

Said, M. S., El Sayed, I. T., Ibrahim, E. E. & Khafagy, G. M. Effect of DASH diet versus healthy dietary advice on the estimated atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk. J. Prim. Care Commun. Heal. 12, 2150132720980952 (2021).

Worm, N. Beyond body weight-loss: Dietary strategies targeting intrahepatic fat in NAFLD. Nutrients 12(5), 1316 (2020).

Vilar-Gomez, E. et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 149(2), 367-378.e5 (2015).

Dayib, M., Larson, J. & Slavin, J. Dietary fibers reduce obesity-related disorders: Mechanisms of action. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 23(6), 445–450 (2020).

Slavin, J. L. & Lloyd, B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv. Nutr. 3(4), 506–516 (2012).

Kim, S., Hong, J., Jeon, R. & Kim, H. S. Adzuki bean ameliorates hepatic lipogenesis and proinflammatory mediator expression in mice fed a high-cholesterol and high-fat diet to induce nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Res. 36(1), 90–100 (2016).

Aguirre, L., Portillo, M. P., Hijona, E. & Bujanda, L. Effects of resveratrol and other polyphenols in hepatic steatosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20(23), 7366–7380 (2014).

Gorzynik-Debicka, M. et al. Potential health benefits of olive oil and plant polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(3), 686 (2018).

Schutte, S. et al. A 12-wk whole-grain wheat intervention protects against hepatic fat: The Graandioos study, a randomized trial in overweight subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108(6), 1264–1274 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contribution of the participants and co-researchers.

Funding

The present study was supported by Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This was a financial support to provide kit and conduct laboratory works.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.P. M.H and A.S. conducted the study, M.H. provided material and technical support, A.S. carried out the statistical analysis, and interpreted the findings, A.S. drafted the manuscript, K.P. critically revised the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The ethical committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences in Tehran confirmed the study protocol and written informed consent. All participants signed the written informed consent before the beginning of the trial (IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1401.016).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sangouni, A.A., Hosseinzadeh, M. & Parastouei, K. Effect of dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet on insulin resistance and lipid accumulation product in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep 15, 17025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01013-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01013-2