Abstract

The association between caffeine and diabetic retinopathy (DR) risk remains controversial. This study aims to examine the association between urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites and self-reported DR risk in US individuals with diabetes. This cross-sectional study enrolled 535 participants with diabetes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2014. The high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry (HPLC–ESI–MS/MS) and internal standards labeled with stable isotopes were used to measure urinary caffeine and fourteen of its metabolites. Urinary caffeine and its metabolites levels were calibrated with urine creatinine for analysis. Caffeine and its metabolites were analyzed as continuous variables and categorical variables (≤ 50% or > 50%). Weighted logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Subgroup analysis by sex was conducted. After adjusting for age, sex, race, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, duration of diabetes, glycated hemoglobin, hypertension, and total energy intake, ln-transformed 1-methyluric acid (1-MU) (OR = 1.27, 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.56, P = 0.016) and 5-acetylamino-6-amino-3-methyluracil (AAMU) (OR = 1.16, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.34, P = 0.043) were associated with an increased DR risk. In median analysis, compared to lower levels (≤ 50%), higher levels (> 50%) of 1,7-dimethyluric acid (1,7-DMU) (OR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.20 to 3.09, P = 0.008), caffeine (OR = 2.00, 95% CI, 1.27 to 3.16, P = 0.004), and AAMU (OR = 1.48, 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.10, P = 0.029) were associated with an increased DR risk. Sex-based analysis showed that ln-transformed 1-MU (OR = 1.48, 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.98, P = 0.012), 1,3,7-TMU (OR = 1.24, 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.49, P = 0.018) and caffeine (OR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.60, P = 0.028) were associated with an increased DR risk in males. Compared to lower levels (≤ 50%), higher levels (> 50%) of 1,7-DMU (OR = 2.75, 95% CI, 1.33 to 5.70, P = 0.008), 1,3,7-TMU (OR = 2.26, 95% CI, 1.02 to 5.01, P = 0.044), caffeine (OR = 3.23, 95% CI, 1.53 to 6.82, P = 0.003), and AAMU (OR = 2.93, 95% CI, 1.16 to 7.40, P = 0.024) were associated with an increased DR risk in males. This study indicated that high urinary levels of 1-MU, 1,7-DMU, 1,3,7-TMU, caffeine and AAMU were associated with an increased risk of DR in US males with DM. Prospective studies are needed to verify these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of diabetes and is one of the main causes of visual impairment and blindness in adults over 501. DR affected an estimated 103 million adults worldwide in 2020, with the number expected to increase to approximately 160 million by 20452. DR has become a critical public health problem due to the increasing global burden of disease3. Although the application of laser photocoagulation and intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy has achieved satisfactory clinical results in the treatment of severe DR, some limitations still exist, such as a high cost and invasive administration route4,5,6. Thus, the identification of modifiable risk factors is crucial to prevent the onset and development of DR and reduce the economic and social burden.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most common metabolic disorders. Dietary approaches are a basic part of DR management, which may be beneficial to prevent complications of DM7. Caffeine is the most widely used active pharmacologic substance worldwide8, and coffee, tea, and soft drinks are predominant sources of caffeine9. Some studies have shown appropriate caffeine intake may be associated with a low risk of DM and cardiovascular diseases10,11, while some studies worried about the side effects of caffeine on human health12,13,14. Moreover, many studies have investigated the effect of caffeine on retinal vascular diseases15,16. Two recent studies reported the protective effect of self-reported caffeine intake for DR in patients with DM17,18. However, previous studies have examined the association between coffee consumption and DR, and the results were controversial19,20. These studies relied on self-reported coffee or caffeine use, and this may cause unavoidable recall bias. The concentrations of urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites are potential biomarkers of caffeine intake21. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the relationship between urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites and DR in patients with DM using a US representative sample of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study used data from the NHANES, a cross-section series of interviews and examinations of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHANES used a stratified multistage sampling methodology with a weighting scheme to accurately assess the health and nutritional status among the US individuals22. NHANES aims to provide the US de-identified health statistics made publicly available. The NHANES was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was collected from all participants. The NCHS research ethics review board reviewed and approved the protocols.

Definition of DM and DR

According to the previous studies23,24, DM was defined as serum fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, 2-hour post-load glucose after oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥ 200 mg/dl, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%, self-reported insulin or diabetes pill use, or self-reported DM.

DR was identified from the question “Has a doctor ever told you that diabetes has affected your eyes or that you had retinopathy”25,26.

Measurements of urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites

Urine samples for participants in this study were collected after a 9-hour overnight fast during the morning session27. The high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry (HPLC–ESI–MS/MS) and internal standards labeled with stable isotopes were used to measure urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites28. Caffeine and 14 caffeine metabolites were examined, including 1-methyluric acid (1-MU), 3-methyluric acid (3-MU), 7-methyluric acid (7-MU), 1,3-dimethyluric acid (1,3-DMU), 1,7-dimethyluric acid (1,7-DMU), 3,7-dimethyluric acid (3,7-DMU), 1,3,7-trimethyluric acid (1,3,7-TMU), 1-methylxanthine (1-MX), 3-methylxanthine (3-MX), 7-methylxanthine (7-MX), 1,3-dimethylxanthine (1,3-DMX), 1,7-dimethylxanthine (paraxanthine, 1,7-DMX), 3,7-dimethylxanthine (theobromine, 3,7-DMX), 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine (caffeine, 1,3,7-TMX), and 5-acetylamino-6-amino-3-methyluracil (AAMU). In cases where the result was below the limits of detection (LODs), the value for that variable is the LOD divided by the square root of two28. In order to control the concentration dilution of urine, urinary caffeine and its metabolites levels were calibrated with urine creatinine for further analysis.

Covariates

The following covariates were included to control the potential effects of confounding factors: Age, sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non–Hispanic White, non–Hispanic Black, or others), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), urine creatinine (mg/dl), smoking (smoking at least 100 cigarettes in life was considered as smokers), and drinking (having at least 12 alcohol drinks per year was considered as alcohol users), HbA1c, self-reported hypertension, and total energy intake (kcal/day). Duration of DM was calculated as the age at the interview minus the age of individuals when first told had DM (< 10 or ≥ 10 years).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed according to the guidelines of CDC for the complex oversampling of data with sample weight. Basic characteristics of the study population are reported as means ± standard deviation (SD) or percentages. The t-test and design-adjusted Rao-Scott Pearson χ2 were used to compare baseline characteristics between different groups. Spearman correlation coefficient analysis was conducted to show the pairwise correlations among these 14 metabolites as well as dietary caffeine intake, we did not adjust for multiple testing because the results were descriptive. To avoid the influence of the skew distribution of urinary caffeine and its metabolites, the natural logarithm-transformed levels were added into the model as continuous variable, and the original concentration was also analyzed in medians (low urinary level: ≤50%; high urinary level: >50%). Logistic regression models were used to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Crude model was not adjusted for any covariate; model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, and race; based on model 1 model 2 was further adjusted for BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, duration of diabetes, hypertension, HbA1c, and total energy intake. Subgroup analysis was performed stratifying by sex, according to the previous study. All analyses were conducted with R software, version 4.3.2. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Data collection

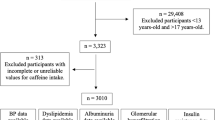

All data was collected from NHANES 2009–2014. A total of 50,974 participants were included in this study. We excluded those participants who were without DM (n = 47789). Participants who did not answer the question for the diagnosis of DR were excluded (n = 1030). Then, participants with missing data on urinary caffeine and its metabolites (n = 1536) and covariates (n = 105) [BMI (n = 10), smoking (n = 3), drinking (n = 46), hypertension (n = 1), diabetes duration (n = 4), total energy intake (n = 21), HbA1c (n = 20)], were excluded. Finally, 514 participants were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Supplementary Table S1 showed the difference between included and excluded participants with diabetes.

Characteristics of the study population

The basic characteristics of the participants were presented in Table 1. The prevalence of DR was 16.9% (87/514) among individuals with DM. No significant variations were found in age, sex, race, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, hypertension, and total energy intake between two groups. DR patients had higher HbA1c and longer duration of DM. Spearman correlation analysis showed significantly positive correlations between metabolites, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.30 to 0.96. (Fig. 2). Caffeine intake showed moderate correlations with nine caffeine metabolites including 1-MU, 1,3-DMU, 1,7-DMU, 1,3,7-TMU, 1-MX, dimethylxanthine (1,3-DMX), paraxanthine (1,7-DMX), caffeine (1,3,7-TMX), and AAMU (Spearman p = 0.52–0.57, P < 0.0001).

Spearman correlation coefficients among 16 substances. Abbreviations: 1-MU, 1-methyluric acid, 3-MU, 3-methyluric acid; 7-MU, 7-methyluric acid; 1,3-DMU, 1,3-dimethyluric acid; 1,7-DMU, 1,7-dimethyluric acid; 3,7-DMU, 3,7-dimethyluric acid; 1,3,7-TMU, 1,3,7-trimethyluric acid; 1-MX, 1-methylxanthine, 3-MX, 3-methylxanthine; 7-MX, 7-methylxanthine; 1,3-DMX, 1,3-dimethylxanthine; 1,7-DMX, 1,7-dimethylxanthine (paraxanthine); 3,7-DMX, 3,7-dimethylxanthine (theobromine); 1,3,7-TMX, 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine (caffeine); AAMU, 5-acetylamino-6-amino-3-methyluracil.

Compared to females, males were prone to be smokers and drinkers. Males had higher energy intake, 1-MU, 1,3-DMU, 1-MX,7-MX, paraxanthine, and AAMU than females (Supplementary Table S2).

The association between urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites concentrations and DR

After adjusting for age, sex, race, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, hypertension, and total energy intake, ln-transformed 1-MU (OR = 1.27, 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.56, P = 0.016) and AAMU (OR = 1.16, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.34, P = 0.043) were associated with an increased DR risk (Table 2).

In the median analysis, compared to lower levels (≤ 50%), higher levels (> 50%) of 1,7-DMU (OR = 1.92, 95% CI, 1.20 to 3.09, P = 0.008), caffeine (OR = 2.00, 95% CI, 1.27 to 3.16, P = 0.004), and AAMU (OR = 1.48, 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.10, P = 0.029) were associated with an increased DR risk (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was conducted stratified by sex. Ln-transformed 1-MU (OR = 1.48, 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.98, P = 0.012), 1,3,7-TMU (OR = 1.24, 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.49, P = 0.018) and caffeine (OR = 1.29, 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.60, P = 0.028) were associated with an increased DR risk in males but not in females (Table 4).

In the median analysis, compared to lower levels (≤ 50%), higher levels (> 50%) of 1,7-DMU (OR = 2.75, 95% CI, 1.33 to 5.70, P = 0.008), 1,3,7-TMU (OR = 2.26, 95% CI, 1.02 to 5.01, P = 0.044), caffeine (OR = 3.23, 95% CI, 1.53 to 6.82, P = 0.003), and AAMU (OR = 2.93, 95% CI, 1.16 to 7.40, P = 0.024) were associated with an increased DR risk in males but not in females (Table 5).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study was the first to explore the association between urinary caffeine and its metabolites and DR risk. After adjusting for age, race, BMI, smoking, alcohol drinking, duration of diabetes, HbA1c, hypertension, and total energy intake, we found that high urinary levels of 1-MU, 1,7-DMU, 1,3,7-TMU, caffeine (1,3,7-TMX) and AAMU were associated with an increased risk of DR in US males with DM. Furthermore, the results of correlation analysis between caffeine metabolites and caffeine intake were strong, and these were consistent with previous studies29,30,31. However, all metabolites are analyzed separately in the different models, but as there is high correlation between the metabolites, it could be that a significant finding of one metabolite could be caused by increases in the other metabolites as well. As these correlations are very strong, it might be that not all three metabolites separately are associated with DR, but only 1,3,7-TMU which as very high correlations with both 1-MU and caffeine (1,3,7-TMX).

Clinical studies on the association between coffee or caffeine and DR risk in the DM patients are still scarce. A previous study has reported coffee intake was not associated with DR in Asians20. Another study also did not find significant association between coffee consumption and the risk of DM microvascular complications in Europeans32. In addition, coffee consumption was inversely correlated with the DR risk in Koreans under 65 years with DM, while this association was not observed over 65 years19. Another study reported intake of caffeine decreased DR risk using NHANES 2003–201817. Moreover, a study with a mean age of 60.4, revealed that high caffeine intake was non-linear rather than linear correlated with reduced DR risk18. Our results were inconsistent with previous studies. Some factors of study design may contribute to this difference. First, food frequency questionnaires and dietary recall are two main methods used to quantify the intake of caffeine/coffee. Despite some advantages such as convenience, these methods rely on self-reported data which lead to unavoidable recall bias33. In addition, coffee usually contains multiple dietary components such as milk and chocolate, and coffee making process varies in different regions that may confuse the real effects of caffeine34,35. Considering these limitations, this study collected urinary caffeine and its metabolites to reflect caffeine intake, and this method was validated useful before29,36,37. Second, the population existed race difference between our studies and previous studies, which focused on Asians19,20 or Europeans18,32. The metabolism, clearance, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of caffeine are significantly affected by race38. Third, DR diagnosis was based on fundus images in several previous studies of the association between coffee/caffeine intake and DR risk18,19. The diagnosis of DR was based on self-reported in this study, and this may underestimate DR prevalence compared with the diagnosis from fundus images39.

The results of experimental studies on the effects of caffeine and caffeine metabolites on DR were controversial. Caffeine is a well-known adenosine receptor antagonist which can cause vasoconstriction and is transformed into three active metabolites including theobromine (11%), theophylline (5%), and paraxanthine (82%) in human liver, catalyzed by cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2)40. Many studies have revealed that caffeine can reduce retinal blood flow and vessel density including macular and peripapillary region41,42,43. The decrease of macular and capillary vessels density were reliable indicators for DR screening44,45, and this may be attributed to increased levels of vascular endothelia growth factors caused by the retinal ischemia and tissue hypoxia46. In addition, recent studies have reported the positive relationship between urinary caffeine and its metabolites and insulin resistance (IR) in the US population31, and IR plays a crucial role in DR development47,48. Two caffeine metabolites including theophylline and theobromine could decrease the angiogenic activity of mononuclear cells in DM patients with proliferative DR49. However, previous studies found that aminophylline (an analogue of theophylline) and theophylline could lead to the formation of active E-rosette in DR patients, indicating abnormal lymphocytes reactivity50,51. Besides, a recent vitro study revealed the protection effects of caffeine on diabetic macular edema, which is the leading cause of vision loss in patients with DR52. In addition, caffeine could inhibit endothelial cell migration in vitro and choroidal neovascularization in vivo16. However, the latest research reported that caffeine eyedrop did not improve either the permeability of retinal vascular or reactive gliosis in db/db mice18. Moreover, an analysis of plasma metabolomic profiling indicated that caffeine metabolism differed between non-DR and proliferative DR in the patients with DM53. Based on these controversial findings, further studies are needed to explore the potential protection effects and mechanisms of caffeine and its metabolites in the onset and development of DR.

In addition, the results of sex-based analysis showed the positive association was significant in males but not in females. Several potential reasons may explain this difference. First, males had higher intake of caffeine and therefore higher urinary caffeine and its metabolites in this study. Second, compared with females, males were prone to be older, smokers, and drinkers. Age and unhealthy lifestyles behaviors are risk factors for DR in patients with DM54. Third, estrogens are reported as competitive inhibitors of caffeine metabolisms and the use of exogenous estrogen may inhibit caffeine metabolism in older females55.

Several limitations existed in this study that should be taken into rigorous consideration when interpreting these results. First, the causality could not be determined ought to the design of a cross-sectional study. Second, DR diagnosis was based on the interview questionnaire rather than retinal images, and this may lead to recall bias and misclassification where other eye conditions may be mistaken for DR. Self-reported DR may underestimate the true prevalence of DR, as undiagnosed or asymptomatic cases are unlikely to be captured, and the severity of DR was not recorded. Third, the single measurement of urine sample provides only a snapshot of metabolite levels, which may not reflect habitual caffeine consumption. Additionally, fasting and the morning-only sample collection may not represent real-world patterns, limiting generalizability. Forth, this study may not be representative of the broader population with diabetes in NHANES due to the high rate of exclusions. Besides, although our findings indicate that the potential DR risk of consuming caffeine for older adults, more research is needed to provide dietary guidelines regarding the caffeine intake. Fifth, this study did not adjust genetic factors, such as CYP1A2 polymorphisms. Sixth, multiple testing was not performed in correlation analysis. However, although multiple testing corrects for number of independent tests and these metabolites are most likely not independent due to their intercorrelation.

Conclusions

This study indicated that high urinary levels of 1-MU, 1,3,7-TMU, and caffeine were associated with an increased risk of DR in US males with DM. Prospective studies are needed to verify these findings in the future.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jampol, L. M., Glassman, A. R. & Sun, J. Evaluation and care of patients with diabetic retinopathy. N Engl. J. Med. 382, 1629–1637. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1909637 (2020).

Teo, Z. L. et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 128, 1580–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Global burden and gender disparity of vision loss associated with diabetes retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 99, 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14644 (2021).

Zhao, M., Sun, Y. & Jiang, Y. Anti-VEGF therapy is not a magic bullet for diabetic retinopathy. Eye (Lond). 34, 609–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0652-3 (2020).

Amoaku, W. M. et al. Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema pathways and management: UK consensus working group. Eye (Lond). 34, 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-0961-6 (2020).

Tan, Y. et al. Anti-VEGF crunch syndrome in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: A review. Surv. Ophthalmol. 66, 926–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.03.001 (2021).

Zheng, Y., Ley, S. H. & Hu, F. B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.151 (2018).

Temple, J. L. et al. The safety of ingested caffeine: A comprehensive review. Front. Psychiatry. 8, 80. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00080 (2017).

Fulgoni, V. L. 3, Keast, D. R., Lieberman, H. R. & rd, & Trends in intake and sources of caffeine in the diets of US adults: 2001–2010. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 101, 1081–1087. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.080077 (2015).

Voskoboinik, A., Koh, Y. & Kistler, P. M. Cardiovascular effects of caffeinated beverages. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 29, 345–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcm.2018.09.019 (2019).

Grosso, G., Godos, J., Galvano, F. & Giovannucci, E. L. Coffee, caffeine, and health outcomes: An umbrella review. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 37, 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064941 (2017).

Rodak, K., Kokot, I. & Kratz, E. M. Caffeine as a factor influencing the functioning of the human Body-Friend or foe?? Nutrients 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093088 (2021).

Voskoboinik, A., Kalman, J. M. & Kistler, P. M. Caffeine and arrhythmias: Time to grind the data. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 4, 425–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2018.01.012 (2018).

Khiali, S. et al. Effect of caffeine consumption on cardiovascular disease: An updated review. Pharmaceut Med. 37, 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-023-00466-y (2023).

Boia, R., Ambrósio, A. F. & Santiago, A. R. Therapeutic opportunities for caffeine and A2A receptor antagonists in retinal diseases. Ophthalmic Res. 55, 212–218. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443893 (2016).

Sorenson, C. M. et al. Caffeine inhibits choroidal neovascularization through mitigation of inflammatory and angiogenesis activities. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 737426. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.737426 (2021).

Zhang, G. et al. Certain dietary nutrients reduce the risk of eye affliction/retinopathy in individuals with diabetes: National health and nutrition examination survey, 2003–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912173 (2022).

Alcubierre, N. et al. Caffeine and the risk of diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Findings from clinical and experimental studies. Nutrients 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15051169 (2023).

Lee, H. J., Park, J. I., Kwon, S. O. & Hwang, D. D. Coffee consumption and diabetic retinopathy in adults with diabetes mellitus. Sci. Rep. 12, 3547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07192-6 (2022).

Kumari, N. Is coffee consumption associated with age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy? All Results J. Biol. 5, 7–13 (2014).

Del Coso, J., Muñoz, G. & Muñoz-Guerra, J. Prevalence of caffeine use in elite athletes following its removal from the world Anti-Doping agency list of banned substances. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 36, 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1139/h11-052 (2011).

U.S. Centers for Disease Control Prevention National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [(accessed on 19 March. (2020). https://www.Cdc.Gov/nchs/nhanes/index.Htm

Wang, H., Guo, Z. & Xu, Y. Association of monocyte-lymphocyte ratio and proliferative diabetic retinopathy in the U.S. Population with type 2 diabetes. J. Transl. Med. 20, 219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03425-4 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Diabetic retinopathy related homeostatic dysregulation and its association with mortality among diabetes patients: A cohort study from NHANES. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 207, 111081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.111081 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Imaging-based body fat distribution and diabetic retinopathy in general US population with diabetes: An NHANES analysis (2003–2006 and 2011–2018). Nutr. Diabetes. 14, 53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-024-00308-z (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999–2018. Jama 326, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.9883 (2021).

U. S. Centers for Disease Control Prevention Laboratory Data Overview, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. [(accessed on 19 March Available online: (2020). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/overviewlab.aspx?BeginYear=2011

Caffeine and Caffeine Metabolites - Urine Lab Procedure Manual (June 2020); https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2013-2014/labmethods/CAFE-H-MET-508.pdf

Rybak, M. E., Sternberg, M. R., Pao, C. I., Ahluwalia, N. & Pfeiffer, C. M. Urine excretion of caffeine and select caffeine metabolites is common in the U.S. Population and associated with caffeine intake. J. Nutr. 145, 766–774. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.205476 (2015).

Arnaud, M. J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of natural methylxanthines in animal and man. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 33–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13443-2_3 (2011).

Lee, S., Min, J. Y. & Min, K. B. Caffeine and caffeine metabolites in relation to insulin resistance and Beta cell function in U.S. Adults. Nutrients 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061783 (2020).

Lin, X. et al. Associations between beverage consumption and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgae242 (2024).

Rios-Leyvraz, M. et al. Monitoring caffeine intake in children with a questionnaire and urine collection: A cross-sectional study in a convenience sample in Switzerland. Eur. J. Nutr. 59, 3537–3543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02187-3 (2020).

Salomone, F., Galvano, F. & Li Volti, G. Molecular bases underlying the hepatoprotective effects of coffee. Nutrients 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9010085 (2017).

Crozier, T. W., Stalmach, A., Lean, M. E. & Crozier, A. Espresso coffees, caffeine and chlorogenic acid intake: Potential health implications. Food Funct. 3, 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1fo10240k (2012).

Ponte, B. et al. Associations of urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites with arterial stiffness in a large population-based study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 93, 586–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.12.010 (2018).

Wu, S. E. & Chen, W. L. Exploring the association between urine caffeine metabolites and urine flow rate: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12092803

Nehlig, A. Interindividual differences in caffeine metabolism and factors driving caffeine consumption. Pharmacol. Rev. 70, 384–411. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.117.014407 (2018).

Nwanyanwu, K., Nunez-Smith, M., Gardner, T. W. & Desai, M. M. Awareness of diabetic retinopathy: Insight from the National health and nutrition examination survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 61, 900–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.018 (2021).

Barreto, G. et al. Novel insights on caffeine supplementation, CYP1A2 genotype, physiological responses and exercise performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 121, 749–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04571-7 (2021).

Lotfi, K. & Grunwald, J. E. The effect of caffeine on the human macular circulation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 32, 3028–3032 (1991).

Karti, O. et al. An optical coherence tomography angiography study. Retina 39, 964–971. https://doi.org/10.1097/iae.0000000000002058 (2019).

Yilmaz Tugan, B. et al. Evaluation of macular and peripapillary vascular parameter change in healthy subjects after caffeine intake using optical coherence tomography angiography. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70, 879–889. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_1989_21 (2022).

Kim, A. Y. et al. Quantifying microvascular density and morphology in diabetic retinopathy using Spectral-Domain optical coherence tomography angiography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, 362–370. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.15-18904 (2016).

AttaAllah, H. R., Mohamed, A. A. M. & Ali, M. A. Macular vessels density in diabetic retinopathy: Quantitative assessment using optical coherence tomography angiography. Int. Ophthalmol. 39, 1845–1859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-018-1013-0 (2019).

Arend, O. et al. Retinal microcirculation in patients with diabetes mellitus: Dynamic and morphological analysis of perifoveal capillary network. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 75, 514–518. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.75.9.514 (1991).

Xu, Y. X. et al. Insulin resistance is associated with the presence and severity of retinopathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 52, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.14344 (2024).

Zheng, Z. & Yu, X. Insulin resistance in the retina: Possible implications for certain ocular diseases. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1415521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1415521 (2024).

Skopiński, P. et al. The effect of TPP, Theophylline and theobromine on the angiogenic activity of mononuclear leucocytes obtained from diabetic patients with proliferative retinopathy. Acta Pol. Pharm. 50, 409–411 (1993).

Antunes, L. J., Barsante, C. F. & Nogueira-Machado, J. A. Effect of corticosteroids and aminophylline on active E-rosette formation in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Metab Pediatr. Syst. Ophthalmol. 10, 84–86 (1987). (1985).

Danilova, A. I. & Dekhtiareva, O. S. [Cellular immunity in patients with diabetes mellitus complicated by diabetic retinopathies]. Probl. Endokrinol (Mosk). 30, 29–34 (1984).

Maugeri, G. et al. Caffeine prevents blood retinal barrier damage in a model, in vitro, of diabetic macular edema. J. Cell. Biochem. 118, 2371–2379. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.25899 (2017).

Zhu, X. R. et al. Plasma metabolomic profiling of proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-019-0358-3 (2019).

Geng, T. et al. Healthy lifestyle behaviors, mediating biomarkers, and risk of microvascular complications among individuals with type 2 diabetes: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 20, e1004135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1004135 (2023).

Pollock, B. G. et al. Inhibition of caffeine metabolism by Estrogen replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 39, 936–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/00912709922008560 (1999).

Funding

This work was supported by the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Special Project (Grant Number J200014) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 81670870).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaodong Chen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jiarui Li: Software. Qianwen Guo: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Ningda Xu: Validation, Supervision, Project administration. Lvzhen Huang and Heng Miao: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because no additional institutional review board approval was required for the secondary analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Guo, Q., Li, J. et al. The association between urinary caffeine and caffeine metabolites and diabetic retinopathy in individuals with diabetes: NHANES 2009–2014. Sci Rep 15, 15827 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01088-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01088-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-omics integrated analysis identifies causal risk factors and therapeutic targets for diabetic retinopathy

Journal of Translational Medicine (2025)