Abstract

Digital images are one of the most regularly used means of storing personal memories and legal proofs. Content modification of digital images is becoming more and more common due to highly advanced image processing tools and techniques. However, digital image modification tools are used to change or hide the digital image content. Copy-move forgery (CMF) is an extensively used image alteration technique in which similar content in that particular digital image alters the contents of the digital image. Many detection methods for CMF have been proposed by various researchers. The keypoint-based CMF detection (CMFD) approach is considered robust and effective. However, the keypoint-based (KB) CMFD approaches are not able to produce satisfactory accuracy, if the tampered regions are small. A novel KB-CMFD approach is presented in this article to detect the small tampered regions in digital images. The CMFD approach proposed in this article is based on the dynamic histogram equalization (DHE), local intensity order pattern (LIOP) as a feature descriptor, and a novel scaled K-means + + (sK-means + +) clustering to detect small regions. The passive KB-CMFD proposed approach performance is evaluated on standard datasets (the CoMoFoD, the MICC-F220, and the defecto MSCOCO (synthetic)). The proposed passive KB- CMFD perform well compared to the other state-of-the-art CMFD approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital image tampering is generally used to hide sensitive information in digital images1 or alter the information in digital images1. The CMF image tampering approach (also called cloning) is widely used for changing the information in the digital image, in which part of the original image is altered with the help of similar parts in the same image2.It is very simple to perform but difficult to identify because the original area and CMF regions are from the same image. Furthermore, image features such as light or dark regions, and so on will be consistent between the tempered areas and the rest of the image. To make the CMFD process more difficult, the culprit applies rotational and scale transformation, color and contract modification on forged digital images. Furthermore, the image may be compressed using some compression algorithms. These factors make the discovery of image forgery even more perplexing. So, the important point in such a CMFD procedure would be the selection of those features from the data that are invariant to the aforementioned post-processing activities. There are two most known CMFD techniques, one is active and the other is passive. The active CMFD technique uses the embedded data stored in the tampered digital images to authenticate the digital image’s legitimacy3.However, the passive CMFD approach does not rely on any such stored data to check image originality4. The passive CMFD approach is more suitable in forensic applications as no stored data is presented before the digital image before tampering. The proposed passive keypoint-based CMFD method has numerous applications in forensic science, including the analysis of digital image evidence and its authenticity presented in court, as well as the verification of viral digital or leaked digital images for their genuineness, which may cause deformation to a specific person. To stop propaganda, the suggested passive keypoint-based CMFD may also be used by major social networks and messaging programs to evaluate the integrity of the digital image that the user is ready to share with the world.

Two more CMFD approaches namely block-based and keypoint-based are used extensively in many CMFD methods. The BB-CMFD divided the input tampered image into fixed-sized blocks i.e.,\((8 \times 8), (6 \times 16), (32 \times 32), \dots\) etc. The features are extracted from those blocks followed by sorting of the blocks usually lexicographical sorting. The sorted blocks are matched with each other to perform CMFD. However, the smaller the block size the more computational cost of the CMFD method, which is why the block-based (BB) CMFD methods are considered slow5. The keypoint-based CMFD method can overcome the computational cost since it does not require dividing the input image into the block like BB-CMFD methods. Moreover, the KB-CMFD methods are more capable of detecting the CMF in regular or even shaped objects e.g., squares, circles, rectangles, and or triangles which are generally low-frequency objects than irregular or uneven-shaped objects e.g., stones, mountains, and trees. The low-frequency objects represent the smooth areas of the image. Since the latest CMFD lacks identification of small CMFs and low-frequency objects in the tampered regions, this is a vital contribution of the proposed CMFD method. The features are extracted from the whole input image e.g., using SURF or SIFT descriptor followed by feature matching. The KB-CMFD methods are considered faster than the BB-CMFD methods6.

The passive KB-CMFD approach is presented in this paper, as KB-CMFD approaches are productive compared with BB-CMFD7,8. Initially, in the passive KB-CMFD approach, the image under observation converted from color to grayscale. Next, the grayscale image is fed into the DHE9, as the DHE enables the proposed passive KB-CMFD method to generate extra energetic features10 via local intensity order pattern (LIOP) descriptor as it can detect regions tampered with affine transformation and JPEG compression11, followed by matching of the generated features by calculating the Euclidean distance of every feature from other. Next, the matched features are passed through the novel sK-means + + clustering method to accurately detect the small tampered regions.

Despite the availability of more sophisticated and cutting-edge descriptors, the use of local intensity order pattern (LIOP) is justified by a number of significant benefits that LIOP provides in the context of copy-move forgery detection. Firstly, LIOP is more resilient to standard image alterations like rotation, scaling, noise addition, and JPEG compression since it was expressly created to record local intensity order patterns rather than absolute intensity values. This is especially helpful in identifying forgeries when a portion of the image has been moved and reproduced, which frequently entails such changes. Secondly, LIOP uses less computing power. Modern descriptors frequently have higher computing complexity even though they might offer more sophisticated properties. LIOP is appropriate for practical use because it achieves a compromise between computational efficiency and feature richness, particularly in real-time applications or when working with huge CMFD datasets. Thirdly, LIOP is made to be unaffected by variations in contrast and lighting, which can be important for forgery detection. It is resistant to changes in illumination or contrast between the original and forged portions of an image because it examines the relative ordering of pixel intensities rather than the actual intensity values. Additionally, although more recent descriptors might be more accurate and sophisticated in some situations, LIOP’s ease of use and ability to differentiate between the original and copied areas of an image make it a dependable tool in practice, particularly in situations where more complicated approaches might not be required or could result in overfitting11.

The main contributions of the proposed passive CMFD approach are as follows:

-

1.

It can detect CMF regions with even or uneven-shaped objects in the tampered image e.g., boxes, balls, stones, cars, and mountains.

-

2.

It effectively and efficiently detects CMF in digital images even after transformation i.e. scaling, rotational, brightness and color changes, etc. due to the robustness of LIOP features against affine and intensity transformations.

-

3.

It can detect small CMF regions in digital images with higher accuracy due to the extraction of information-rich features in the small and smooth regions using sK-means + + clustering and DHE features.

-

4.

Its computational complexity is less in contrast with other CMFD approaches.

Literature review

In the last two decades, researchers have proposed many CMF detection methods. In12, a blocked-based CMFD methodology is presented, which uses the BB-CMFD. However, the CMFD method only detects a single tampered region in the image without any robustness against any operations to make the CMF detection process difficult. Additionally, a different BB-CMFD in Ardizzone et al.13 is discussed, it uses triangles instead of blocks for the CMFD method. The technique can detect affine transformation on tampered images. The proposed CMFD method shows good results in terms of precision and recall, however, the proposed CMFD method is computationally complex when matched with the state-of-the-art CMFD methods. Moreover, its performance gets worse for the complex structure tampered images. Discrete coefficient transform (DCT) based feature used by Hayat et al.14. In15, Hosny et. al. proposed a CMFD method that uses PCET to detect the tampered regions in digital images. The proposed technique shows good results in tampered images with post-processing attacks; however, the technique shows high computational cost. The use of DCT and discrete wavelet transform (DWT) improved the CMFD process. The DCT allows the proposed CMFD method, faster detection of the features from the tampered image. The DWT narrowed down the feature vector set to make feature-matching processes faster. However, the proposed CMFD method cannot detect multiple tampered regions as well as the performance decrease for the small tampered regions due to fewer number features. In16 a BB-CMFD method which utilizes DCT and Euclidean distance for feature matching is presented. The proposed CMFD method uses a BB-CMFD. The proposed CMFD method uses a different size of the blocks for accuracy improvement; it promptly bears the computational cost. A KB-CMFD by Silva et al17,which utilizes the speeded-up robust feature (SURF) descriptor for feature extraction and pyramidal decomposition to reduce search space. The proposed CMFD method uses Hue, Saturation, and Value (HSV), color scheme to transform the input image in the pre-processing to generate energetic features. Due to the use of a keypoint-based approach, the feature extraction of the proposed CMFD method is very fast and can detect multiple CMF regions as well as robust against JPEG compression, brightness change, and additive noise. However, the proposed CMFD methods fail on minor forged areas of the image. The review study done by Warbhe et al.7 shows that SURF descriptors perform better than scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) descriptors.

A CMF detection method proposed by Manu et al.18, utilizes patch matching, and Fourier-Mellin transforms (FMT) for CMF detection. The proposed CMFD method is slow as well and the detection of the small tampered regions is not coped within the proposed CMFD method. A multi-level dense descriptor (MLSS) in19 is utilized for feature extraction from the tampered image. The matching of the features is carried out by using hierarchical feature matching (HFM) which is robust against scale, and rotational transformation. However, the computational cost of the proposed CMFD method is very high compared to the state-of-the-art CMFD methods. Another CMF detection method uses a convolution neural network (CNN), by Yuan et al.20. The proposed CMFD utilizes the log-polar expansion to improve the detection and extraction of the features from the input image. The proposed CMFD method identifies the multiple CMF regions in the digital image as well as robustness against scale, and rotational transformation. However, the computational cost of the proposed CMFD method increased due to the hefty detection of the features vector set. The interest point-based CMFD in Zandi et al.21 fuses the block and keypoint-based techniques. The features are denser crowded which makes the feature detection and matching process very slow. However, the proposed method performs well in contrast with other methodologies in CMF. Another CMF detection method that KAZE and SIFT feature proposed by Yang et al.22 appeared to be robust against geometric transform on tampered regions. The KAZE descriptor identifies the forged areas with affine transformation and brightness change. Nevertheless, the complexity of this descriptor is enormous. Another hybrid features-based CMFD is proposed by Pandey et al.23, it fuses the features of HOG, SIFT, and SURF for CMFD, with good precision but slow processing. Also, the proposed CMFD method fails for multiple forged areas. Yu et al. 24, utilize the MROGH descriptor in the CMFD method, which performs well against affine transformation, and JPEG compression. In25, a SIFT descriptor-based CMFD method utilizes a keypoint distribution for feature extraction and agglomerative hierarchical clustering (AHC) for feature matching. The accuracy of the proposed CMFD is significantly high due to the high number of keypoint by using the keypoint distribution. However, the high number of keypoint results into high CPU time which makes the proposed CMFD slow. Another SURF-based CMFD method was proposed in26. In this approach, the large size of the block enables the process fast; this CMFD method suggests that increasing the block size also increases the accuracy of CMFD. However, the proposed CMFD detects similar areas also as forged making the false detection rate also high.

Lin et al.28 developed a method for detecting image modifications using hybrid characteristics. The keypoints from the suspicious image are first generated using the LIOP and SIFT descriptors. Then, to improve the matching relation of computed characteristics, transitive matching is used. Following that, an image segmentation-based filtering technique is employed to discover false matches. Finally, affine modifications are computed across discovered keypoints to recognize the CMF region. The methodology in28 performs superior CMFD under several post-processing attacks such as scaling, noise addition, and so on, but has required high computational power. Arthur et al.27 presented a CMFD method. The SIFT descriptor is used to calculate the features, then the features are identified using Hu’s invariant moments. Finally, the CMF regions are detected using Hu’s invariant moment estimations. The approach achieved improved copy-move forgery detection results, but its detection effectiveness declined for small and thin copied regions. Moreover, for flat forged regions, the SIFT approach may not perform well. Shinde et al.28proposed a deep-learning-based CMFD, which utilized a Graph Convolution Network (GCN) for feature extraction and a Support Vector Machine (SVM) for the classification of the authentic and forged images, however, it cannot detect small forged areas. Zhong et al.29 suggested a Dense-InceptionNET deep-learning (DL) framework for recognizing the CMF. To begin, the features are extracted using the pyramid feature extractor (PFE). The extracted features are matched using the Feature Correlation Matching (FCM) to assist in detecting the CMF regions. Finally, hierarchical post-processing (HPP) for lesser false matches improves performance but lowers its efficiency. Roy et al.30 proposed a method for CMFD. The SURF descriptor is used to identify image keypoints in the first step, after which a rotated local binary pattern (RLBP) is used to form a feature set. Later, to compare features, the g2NN keypoints similarity measurement approach is used. Finally, the manipulated content is displayed using hierarchical agglomerative clustering. This technique improves CMFD performance but fails in flat regions. Zhu et al.31 demonstrated a deep learning-based method for detecting CMF regions. This approach introduces a fully connected NN made up of Adaptive attention and Residual Refinement Network (AR-Net). To begin, an adaptive attention module is used to learn the deep features. Deep matching is then used to calculate the self-correlation among keypoints maps in the following step. The coarse mask is then produced by fusing the computed maps using atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP). This method improves CMFD accuracy but with the cost of more computational power. These approaches32 contribute to the improvement and precision of structural health assessments for bridges by employing knowledge-driven methods that concentrate on identifying tampering in monitoring images, or by integrating image forensics with machine learning for anomaly detection using data-driven approaches. The method described in33 employs block-based DCT to divide the image into smaller sections. From each block, DCT coefficients are taken, and Eigenvalues are calculated from these coefficients to create feature vectors. This technique ensures robustness against rotation, allowing it to function effectively even when the copied area is rotated. The performance assessment is carried out on standard benchmark datasets to evaluate detection accuracy and resistance to rotation. The results of the experiments show that this method is successful in accurately identifying and locating copy-move forgeries, even in cases involving rotation. In today’s digital age, images are extensively utilized in various settings i.e. print and digital media, and in the court of law. The strategy outlined in34 combines image enhancement filters with frequency-based forgery detection filters. This combination aims to not only improve image quality but also identify copy-move forgeries, offering a comprehensive solution for authenticating images on social media platforms. The process begins with a two-step pre-processing stage. The first step involves automatically selecting images, while the second step focuses on enhancing the chosen images using filters to enhance their quality. The improved images then undergo frequency-based CMFD to identify instances of copy-move forgeries.

The technique in35 presents a layer-by-layer decoupling refinement mechanism that improves the accuracy of identifying duplicated regions by methodically separating and analyzing image features at several levels. This method improves the network’s capacity to manage intricate forgeries, such as those impacted by compression, noise, or other post-processing adjustments. The network maintains robustness against different distortions while achieving excellent accuracy in recognizing tampered regions through iterative feature refinement. The method’s higher performance over current techniques, especially in difficult settings, is demonstrated by experimental results, underscoring its potential for dependable and useful applications in image authentication and digital forensics. To achieve high accuracy in forgery detection, the authors in36 suggest a two-stage hybrid strategy that combines the advantages of keypoint-based algorithms and convolution neural networks (CNNs). While keypoint matching is used in the second step to refine and validate the discovered regions, a CNN is used in the first stage to find possible regions of interest. By combining the accuracy of keypoint analysis with the discriminative power of deep learning, this hybrid approach successfully overcomes the drawbacks of conventional techniques, including false positives and computational inefficiency. The experimental findings show that the suggested method is more reliable and effective than current techniques, especially when dealing with complicated and noisy images. By simplifying the image data using dimensionality reduction techniques, the method in37 improves the efficiency of the CMF detection process. The authors also present a twofold quantization feature extraction technique that captures minute changes in pixel values, improving the capacity to detect duplicated regions. This dual strategy is appropriate for large-scale analysis of images since it lowers computational complexity while simultaneously increasing the accuracy of forged region detection. The experimental findings emphasize the method’s potential for real-world uses in digital forensics and image authentication by showing how well it detects copy-move forgeries even in the presence of noise and post-processing operations in images. An enhanced deep learning-based method for identifying copy-move forgeries in digital images is presented by the authors in38. The suggested approach maintains excellent detection accuracy while lowering computing overhead by focusing on regions of interest via a selective sampling attention technique. Furthermore, by examining spatial linkages and feature similarities within the image, the network integrates a low-cost two-step self-correlation calculation to effectively identify duplicated regions. Even when faced with challenging scenarios like noise or post-processing alterations, the network’s capacity to identify subtle forgeries is improved by this two-step procedure. The experimental findings show that the method outperforms current approaches in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency, making it a viable option for real-world uses in tampering detection and image forensics.

Methodology

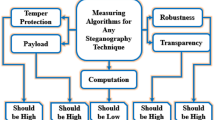

In the first stage of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method, the grayscale transformation is applied to the digital images. The grayscale tampered image is processed by DHE to enhance the grayscale image. The DHE-enhanced input image is processed using LIOP for feature extraction, followed by matching the features using Euclidean distance. The matched features are subjected to the sK-means + + clustering method to identify forged areas. The Fig. 1 shows the block diagram of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method.

Apply DHE on pre-processed grayscale input tampered image

The grayed-scaled image is fed into the DHE39. The DHE utilizes the traced local maxima (TLM) to enhance the contrast of the image, which only enhances the overall contrast of the image without disturbing the spatial information of the image. The DHE uses Eq. (1) to allocate the dynamic grey level (DGL) range to the sub-histogram of the tampered image.

where \(y\) is the weight given to the frequency, \(Dyn{R}_{i}\) is the DGL range for \({i}^{th}\) sub-histogram in the output image,\(sp\) is the DGL range for \({i}^{th}\) sub-histogram in the input image and \(CFrq\) is the addition of histogram values at \({i}^{th}\) sub-histogram and \(L\) is the grey level.

Feature extraction using LIOP descriptor

The DHE’ed image is fed into the LIOP descriptor11 to extract features. The LIOP descriptor uses small regions of the local patch from the tampered image known as ordinal bins, to construct the descriptors. The constructed descriptor of LIOP is then used to generate the features. The details of the LIOP descriptor are described in the subsequent subsections.

Feature detection and normalization

The LIOP descriptor uses the Hessian affine detector to detect the features in the processed input image as it helps in estimating the shape of the detector feature and its neighbors. As the features detected by the Hessian affine detector27, there is a possibility that most of the features detected in various parts of the processed image have different sizes. To cope with the varying size issues of the features detected in those parts, the normalization is carried out on the detected features in a fixed circular shape. In the end, the regions are smoothed out using a Gaussian smoothing filter to remove any noise.

Histogram sub-regions

In the LIOP descriptor, the main key feature is the individuality of the parts of the detected feature. This individuality is achieved by generating the histogram of each divided part, followed by combining them into one histogram region. The sub-regions are generally equally sized circular-shaped bins known as ordinal bins. These ordinal bins are invariant to not only rotations and brightness changes but also the size of the detected features.

Feature vector formation

In this step, the ordinal bins from previous sections are combined and fed into the LIOP descriptor to extract features as presented in Eq. (2). The local ordinal information of each pixel of the image is encoded using a LIOP descriptor, and the overall ordinal information is used to partition the local patch into sub-regions, which are then used to accumulate the LIOPs. As a result, the LIOP descriptor captures high-quality features, making it a highly discriminative descriptor. It is resistant to a variety of geometric and photometric modifications, including viewpoint change, image blur, and JEPG compression, in addition to monotonic intensity variations and image rotation.

where the \(Des{p}_{LIOP}\) represents the LIOP descriptor, \(OB\) represents an ordinal bin, \(N\) represents the bins count, which is set to 64, and \(x\) represents the point at the sub-region. To increase the reliability of the LIOP descriptor, the less similar features are weighted high as they are more stable. Equation (3) can be then rewritten as follows, where \(w\left(x\right)\) is assigned weight for less similar features.

LIOP descriptor features matching

Now using the Euclidean distance defined in Eq. (4), the generated features are matched.

where \(X \text{and} Y\) are the feature vectors (and X = {x1, x2,…, xn } and Y = {y1, y2,…, yn}), the length of each feature vector is \(64\times n\), and \(d\) is the Euclidian distance between those feature vectors. The ratio of distances between the two features can be expressed as shown in Eq. (5). Here \(T\) is set to \(0.6\) due to the optimal performance of the proposed approach.

The extracted and matched LIOP descriptor features are shown in Fig. 2.

Novel sK-means + + clustering method

In the novel sK-means + + clustering method, the matched features from the LIOP descriptor are grouped into clusters to accurately detect small tampered regions in the digital image. The k-means + + was first proposed in27, where the target is to identify the center of the cluster using the k-means clustering method. Next, the weighted probability is calculated using Eq. (6).

where \(Dist(x)\) is the distance between the selected center and the data point. Repeat this step until the \(k\) numbers of centers have been selected, followed by the standard k-means clustering method for \(k\) centres. The generated clusters have fewer false matches as shown in Fig. 3. Finally, the grayscale mask is created from k-means + + clusters as shown in Fig. 4.

Prior to applying the clustering algorithm in the proposed passive KB-CMFD approach, data must be scaled to guarantee that every feature contributes equally to the distance computations. Suboptimal clustering outcomes might arise from the clustering process favoring features with broader ranges when features have different scales. Thus, the advantages of both scaling and better centroid initialization are combined in the proposed passive KB-CMFD approach when scaled data and k-means + + initialization are used. When compared to using unscaled data with standard k-means + + initialization, this combination usually yields more accurate and effective clustering. In the proposed novel sK-means + + clustering method, the grayscale mask size is increased by a factor of \(2\),which results in more features being extracted using the LIOP descriptor and matching as shown in Fig. 5(a-c), respectively. By sampling each data point independently and updating sampling probabilities less frequently, the sKmeans + + clustering accelerates initialization. Independent sampling of data points allows for parallel processing, which delivers fast processing over K-means + + clustering as well as improved accuracy. The algorithm of the sK-means + + clustering is presented as follows:

Morphological binary operation and localization

Finally, the result from the sK-means + + clustering method, the morphological binary operations are applied to detect and localize the forged regions in the input tampered image as shown in Fig. 6.

Experimental setup, results, and discussions

The performance of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method has been evaluated using three standard datasets, namely CoMoFoD (Copy-Move Forgery Detection)40, MICC-F220 (Media Integration and Communication Center-Forensic 220)41, and Defecto MSCOCO (Microsoft Common Objects in Context) (synthetic dataset)42. The CoMoFoD dataset is specifically designed for evaluating copy-move forgery detection algorithms. It consists of 260 images with varying resolutions, such as 512 × 512 pixels and 3000 × 2000 pixels, and aspect ratios. This dataset includes synthetic images created by copying and pasting regions within the same image to generate instances of copy-move forgeries. Ground truth annotations are provided to indicate the location of the forged regions within each image. It encompasses a wide range of images with different content, resolutions, and complexities, enabling a comprehensive evaluation of forgery detection algorithms. On the other hand, the MICC-F220 dataset comprises 220 images with resolutions ranging from 722 × 480 pixels to 800 × 600 pixels. These images are obtained from diverse sources, including natural scenes, objects, and indoor scenes. Each image in this dataset is manually annotated with various types of manipulations like CMF, and splicing. The MICC-F220 dataset offers a challenging and diverse collection of images to assess the robustness and generalization capabilities of forgery detection algorithms across different types of image manipulations. The Defecto MSCOCO dataset (synthetic dataset) uses MSCOCO images and alter them to perform CMF in the images which altered more than 18 thousand images from MSCOCO.

Evaluation criteria

The performance evaluation of the proposed passive CMFD approach is carried out using three standard parameters namely precision (P), recall (R), and \({F}_{measure}\). These metrics are essential for quantitatively evaluating the effectiveness of copy-move forgery detection techniques, providing insights into their accuracy, sensitivity, and overall performance. These metrics provide a comprehensive understanding of a CMFD approach’s ability to detect copy-move forgeries accurately while minimizing false positives and false negatives as described below.

Precision

The precision (P) (also known as specificity) measures the accuracy of positive predictions made by the forgery detection technique. It indicates the proportion of detected forged regions that are correctly identified as such among all regions that the technique labels as forged.

Recall

The recall (R) (also known as sensitivity) measures the ability of the forgery detection technique to correctly identify all actual forged regions in the image. It indicates the proportion of actual forged regions that are correctly identified by the technique.

F-measure

The F-measure (\({F}_{measure}\)) (also known as \(F{1}_{score}\)) combines precision and recall into a single metric, providing a balanced assessment of the forgery detection technique performance. Evaluation is carried out using three standard parameters, precision (P), recall (R), and \({F}_{measure}\), using Eqs. (7–9), respectively.

where \({T}_{P}, {F}_{P},\) and \({F}_{N}\) represent several correctly detected tampered regions, falsely detected tampered regions, and missed tampered regions, respectively.

Small and various shaped forge region detection

This test is conducted on the CoMoFoD dataset since it has a wide range of tampered images having multiple and small tampered regions within the images as shown in Fig. 7(i-iv). The small tampered regions are those whose pixel count is relatively less than a standard count of 100 pixels of the image. The performances of the proposed passive CMFD method which utilizes novel scaled K-means + + clustering and standard k-means + + clustering method are presented in Table 1. This indicates that the proposed novel sK-means + + clustering approach produces better performance as compared with the standard k-means + + clustering, however, its CPU time is slightly high, which can be negligible.

Post-processing operation tests

The evaluation of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method for its robustness against the post-processing operation is conducted using the CoMoFoD dataset. The LIOP detector can identify copy-move forgery in images even after post-processing attacks such as scale transformation, rotational transformation, blurring, JPEG compression, color reduction, brightness change, contrast adjustment, and additive noise. However, the success of detection depends on various aspects, including the extent of the post-processing used, the quality of the original and altered photos, and the settings chosen for the LIOP detector. The LIOP features are resistant to certain transformations and distortions, including several post-processing. They record the local intensity distribution patterns in an image, which can be reasonably invariant to changes in lighting conditions, tiny geometric alterations, and some types of noise. The following are the tests for the post-processing operations.

Scale transformation

In the scale transformation, the image is reduced by \(0.65\). The original and the tampered image with scale transformation are shown in Fig. 8(i) and (ii) of the first row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 8(iii) and (iv) first column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the scale transformation results are presented in Table 2.

Rotational transformation

In the rotational transformation, the angle of the image from CoMoFoD is rotated by \(50^\circ\). The original image and the tampered image with rotational transformation are shown in Fig. 8(i) and (ii) of the second row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 8(iii) and (iv) second column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the rotational transformation results are presented in Table 2.

Blurring

In the blurring, the image from the CoMoFoD dataset is blurred by applying the averaging filter \((7\times 7)\). The original image and the tampered image with blurring can be seen in Fig. 8(i), and (ii) of the third row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 8(iii) and (iv) third column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the blurring results are presented in Table 2.

JPEG Compression

In the JPEG compression, the quality of the image from the CoMoFoD dataset is degraded using the quality factor of \(50\). The original image and the tampered image with blurring can be seen in Fig. 8(i), and (ii) of the fourth row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 8(iii) and (iv) fourth column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the JPEG compression results are presented in Table 2.

Brightness change

In the brightness change, the brightness of the image from the CoMoFoD dataset is changed by setting the lower and upper bound of the color map at \((0.01, 0.8)\). The original image and the tampered image with brightness change are shown in Fig. 9(i), and (ii) of the second row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 9(iii) and (iv) second column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the brightness change results are presented in Table 2.

Contrast adjustment

In contrast adjustment, the contrast of the image from the CoMoFoD dataset is attuned by setting the upper and lower limit of the color map at \((0.01, 0.95)\). The original image and the tampered image with contrast adjustment are shown in Fig. 9(i), and (ii) of the third row. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 9(iii) and (iv) third column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the contrast adjustment results are presented in Table 2.

Additive noise

In the additive noise case, the additive noise is added in the image from the CoMoFoD dataset using the averaging filter \((5\times 5)\). The original image and the tampered image with additive noise are shown in Fig. 9(i), and (ii) of the fourth row. The CoMoFoD dataset makes no explicit mention of the type or features of the additive noise applied to the images. Additive noise is defined as random fluctuations in pixel values applied to an image, generally to imitate noise that may occur during image acquisition or transmission. Gaussian noise, salt-and-pepper noise, speckle noise, and random noise are some common types of additive noise. The result from the proposed passive KB-CMFD method and the ground truth are shown in Fig. 9(iii) and (iv) fourth column, respectively. The \(P, R,\) and \({F}_{measure}\) of the additive noise results of the proposed approach are presented in Table 2.

Performance analysis in terms of evaluation parameters

The evaluation and comparison test of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method with state-of-the-art CMFD methods is carried out on standard datasets namely CoMoFoD40, and MICC-F22041, Defecto MSCOCO (synthetic)42 and experimental results are presented in Table 3. The experimental results of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method for the MICC-F220 and defecto MSCOCO datasets are shown in Fig. 10(i-iv) and Fig. 11(i-iv), respectively. According to the experimental details given in Table 3, the proposed passive KB-CMFD method outclasses the rest by better performance in terms of \(P\),\(R\), and \({F}_{measure}\). The sK-means + + clustering increases the accuracy of regular and small-sized forgery detection of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method. The DHE-based LIOP feature descriptor helps fast extract the tampered image features with rotational, scale invariance, robustness against brightness changes, and additive noise.

Performance analysis in terms of computational time

Using the MICC-F220 dataset, the computation cost of the proposed passive KB-CMFD method is calculated and its comparative analysis is performed with state-of-the-art CMFD methods (i.e. block-based12, hybrid feature-based22, SIFT feature-based25, and SURF feature-based26). Its computation time is assessed on a desktop PC with following software and hardware resources: Windows 10 (64 bit), MATLAB 2017B (64 bit), VLFeat 0.9.21-MATLAB library, CPU: Intel Core i7@2.10 GHz, RAM: 8GB, Hard disc: 500GB. The proposed CMF detection method shows better time efficiency according to the details mentioned in Table 4 due to the use of the DHE, LIOP features, and sK-means + + clustering as compared with state-of-the-art CMFD methods.

Conclusion and future directions

The experimental results presented in this article show that the proposed passive KB-CMFD approach performs superior when compared with other CMFD. The DHE and LIOP descriptors provided the ability for the proposed passive KB-CMFD approach to detect the most energetic features to improve accuracy and efficiency. Since the DHE enhanced the contrast of the tampered image to generate plentiful features. Furthermore, the LIOP features allow the proposed passive KB-CMFD approach to extract robust features against affine and intensities transformations. The proposed novel scaled k-means + + clustering approach helps in identifying the small forged regions by extracting the hefty and most energy-rich features from the small and smooth CMF regions. However, there is still room for enhancement in identifying extremely smooth forged areas. Hence, the proposed passive KB-CMFD method is currently undergoing improvements. Moving forward, initial investigation is necessary for the CMF regions within the image, which are notably smooth and heavily compressed. Additionally, given the recent progress in deep learning, there is a rising interest in utilizing convolution neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning structures for detecting copy-move forgeries. It is worth exploring the application of deep learning techniques for feature acquisition, end-to-end forgery detection, and enhancing detection precision across various datasets. Lastly, considering the rise of new technologies like augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and deep fakes, there is a demand for advanced forensic methods to identify and analyze forgeries in these contexts. Future studies could concentrate on creating specialized forgery detection approaches tailored to the features and obstacles of these emerging technologies.

Data availability

The authors used publicly available data to support the study’s findings, which are included in the article.

References

Belk, R. W. Extended self in a digital world. J. Consum. Res. 40(3), 477–500 (2013).

Christlein, V. et al. An evaluation of popular copy-move forgery detection approaches. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 7(6), 1841–1854 (2012).

Qureshi, M. A. & Deriche, M. A bibliography of pixel-based blind image forgery detection techniques. Signal Process. Image Commun. 39(1), 46–74 (2015).

Asghar, K., Habib, Z. & Hussain, M. Copy-move and splicing image forgery detection and localization techniques: a review. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 49(3), 281–307 (2017).

Kirchner, M., P. Schoettle, and C. Riess. Thinking beyond the block: block matching for copy-move forgery detection revisited. in Media Watermarking, Security, and Forensics 2015. In: 2015 International Society for Optics and Photonics.

Chauhan, D. et al. Survey on keypoint based copy-move forgery detection methods on image. Proc. Comput. Sci. 85, 206–212 (2016).

Warbhe, A. D., Dharaskar, R. & Thakare, V. A survey on keypoint based copy-paste forgery detection techniques. Proc. Comput. Sci. 78, 61–67 (2016).

Soni, B., Das, P. K. & Thounaojam, D. M. CMFD: a detailed review of block based and key feature based techniques in image copy-move forgery detection. IET Image Proc. 12(2), 167–178 (2017).

Garud, H., et al. Brightness preserving contrast enhancement in digital pathology. In: 2011 International Conference on Image Information Processing. 2011. IEEE.

Tu, L., C. Dong. Histogram equalization and image feature matching. In: 2013 6th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing (CISP). 2013. IEEE.

Wang, Z., B. Fan, and F. Wu. Local intensity order pattern for feature description. In: 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision. 2011. IEEE.

Fridrich, A.J., B.D. Soukal, and A.J. Lukáš. Detection of copy-move forgery in digital images. In: Proceedings of Digital Forensic Research Workshop. 2003. Citeseer.

Ardizzone, E., Bruno, A. & Mazzola, G. Copy–move forgery detection by matching triangles of keypoints. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 10(10), 2084–2094 (2015).

Hayat, K. & Qazi, T. Forgery detection in digital images via discrete wavelet and discrete cosine transforms. Comput. Electr. Eng. 62(6), 448–458 (2017).

Hosny, K. M., Hamza, H. M. & Lashin, N. A. Copy-move forgery detection of duplicated objects using accurate PCET moments and morphological operators. Imag. Sci. J. 66(6), 330–345 (2018).

Alkawaz, M. H. et al. Detection of copy-move image forgery based on discrete cosine transform. Neural Comput. Appl. 30(1), 183–192 (2018).

Silva, E. et al. Going deeper into copy-move forgery detection: Exploring image telltales via multi-scale analysis and voting processes. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 29(5), 16–32 (2015).

Manu, V. & Mehtre, B. M. Copy-move tampering detection using affine transformation property preservation on clustered keypoints. SIViP 12(3), 549–556 (2018).

Bi, X., Pun, C.-M. & Yuan, X.-C. Multi-level dense descriptor and hierarchical feature matching for copy–move forgery detection. Inf. Sci. 345, 226–242 (2016).

Yuan, Y. et al. Robust region duplication detection on log-polar domain using band limitation. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 42(2), 559–565 (2017).

Zandi, M., Mahmoudi-Aznaveh, A. & Talebpour, A. Iterative copy-move forgery detection based on a new interest point detector. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 11(11), 2499–2512 (2016).

Yang, F. et al. Copy-move forgery detection based on hybrid features. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 59(3), 73–83 (2017).

Pandey, R.C., et al. Fast and robust passive copy-move forgery detection using SURF and SIFT image features. In: 2014 9th International conference on industrial and information systems (ICIIS). 2014. Gwalior, India: IEEE.

Yu, L., Han, Q. & Niu, X. Feature point-based copy-move forgery detection: covering the non-textured areas. Multimedia Tools Appl. 75(2), 1159–1176 (2016).

Yang, B. et al. A copy-move forgery detection method based on CMFD-SIFT. Multimedia Tools Appl. 77(1), 837–855 (2018).

Soni, B., P.K. Das, and D.M. Thounaojam. Improved Block-based Technique using SURF and FAST Keypoints Matching for Copy-Move Attack Detection. In: 2018 5th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN). 2018. Noida, India: IEEE.

Arthur, D. & Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The advantages of careful seeding (Stanford, 2006).

Shinde, V. et al. Copy-move forgery detection technique using Graph Convolutional Networks feature extraction. IEEE Access 12, 121675–121687 (2024).

Zhong, J. et al. A new block-based method for copy move forgery detection under image geometric transforms. Multimedia Tools Appl. 76(13), 14887–14903 (2017).

Roy, A. et al. Copy-Move Forgery Detection with Similar But Genuine Objects. In Digital Image Forensics 65–77 (Springer, 2020).

Zhu, Y. et al. AR-Net: Adaptive attention and residual refinement network for copy-move forgery detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 16(10), 6714–6723 (2020).

Wan, S., Guan, S. & Tang, Y. Advancing bridge structural health monitoring: Insights into knowledge-driven and data-driven approaches. J. Data Sci. Intel. Syst. 2(3), 129–140 (2024).

Shehin, A. & Sankar, D. Copy move forgery detection and localisation robust to rotation using block based discrete cosine transform and eigenvalues. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 99, 104075 (2024).

Abir, N. A. M., Warif, N. B. A. & Zainal, N. An automatic enhanced filters with frequency-based copy-move forgery detection for social media images. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83(1), 1513–1538 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Strong robust copy-move forgery detection network based on layer-by-layer decoupling refinement. Inf. Process. Manage. 61(3), 103685 (2024).

Diwan, A. & Roy, A. K. Cnn-keypoint based two-stage hybrid approach for copy-move forgery detection. IEEE Access 12, 43809–43826 (2024).

Wu, S., Wu, Z. & Huang, M. Copy-move forgery detection via dimensionality reduction and double quantization feature. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1587/transinf.2024EDP7249 (2025).

Shi, Y. et al. A copy-move forgery detection network based on selective sampling attention and low-cost two-step self-correlation calculation. IEEE Trans. Multimedia https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2025.3535369 (2025).

Szeliski, R. Computer vision: algorithms and applications (Springer, 2010).

Tralic, D., et al. CoMoFoD—New database for copy-move forgery detection. In: ELMAR, 2013 55th international symposium. 2013. Zadar, Croatia: IEEE.

Amerini, I. et al. A sift-based forensic method for copy–move attack detection and transformation recovery. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 6(3), 1099–1110 (2011).

Lin, T.-Y., et al. Microsoft coco: Common objects in context. In: Computer vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, proceedings, part v 13. 2014. Springer.

Chen, C.-C., Lu, W.-Y. & Chou, C.-H. Rotational copy-move forgery detection using SIFT and region growing strategies. Multimedia Tools Appl. 78(13), 18293–18308 (2019).

Mehmood, Z. et al. Passive framework of sparse region duplication detection from digital images. J. Sensors 2022, 1–16 (2022).

Cozzolino, D., Poggi, G. & Verdoliva, L. Efficient dense-field copy–move forgery detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 10(11), 2284–2297 (2015).

Thampi, S. M., Gelbukh, A. & Mukhopadhyay, J. Advances in signal processing and intelligent recognition systems (Springer, 2014).

Mukherjee, S., Pal, A. K. & Maji, S. A copy-move forgery detection technique using DBSCAN-based keypoint similarity matching. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 15(12), 5607–5634 (2024).

Jaiswal, A. K. & Srivastava, R. Detection of copy-move forgery in digital image using multi-scale, multi-stage deep learning model. Neural Process. Lett. 54(1), 75–100 (2022).

Abdel-Basset, M. et al. 2-Levels of clustering strategy to detect and locate copy-move forgery in digital images. Multimedia Tools Appl. 79, 5419–5437 (2018).

Soni, B., Das, P. K. & Thounaojam, D. M. Geometric transformation invariant block based copy-move forgery detection using fast and efficient hybrid local features. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 45, 44–51 (2019).

Ibrahim, Z.S., and T.M. Hasan. Copy-Move Image Forgery Detection using Deep Learning Approaches. In: 2024 First International Conference on Software, Systems and Information Technology (SSITCON). 2024. IEEE.

Li, Y. et al. Image copy-move forgery detection via deep patchmatch and pairwise ranking learning. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 34, 425–440 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. A serial image copy-move forgery localization scheme with source/target distinguishment. IEEE Trans. Multimedia 23, 3506–3517 (2021).

Islam, A., et al. DOA-GAN: Dual-order attentive generative adversarial network for image copy-move forgery detection and localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2020.

Wu, Y., W. Abd-Almageed, and P. Natarajan. Busternet: Detecting copy-move image forgery with source/target localization. In: Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV). 2018.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Funding

This work was partly supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation(IITP)-Innovative Human Resource Development for Local Intellectualization program grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT)(IITP-2025-RS-2023-00259678) and by the IITP(Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation)- ITRC(Information Technology Research Center) grant funded by the Korea government(Ministry of Science and ICT)(IITP-2024-RS-2024-00438335).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, ZM, MB, AM, AMC, JR, JK; data curation, ZM, MB; funding acquisition JR, JK; investigation, ZM, MB, AM, AMC, JR, JK; methodology, ZM, MB, AM, AMC, JR, JK; software, ZM, MB, AM, AMC, JR, JK; validation, ZM, MB, AM, AMC, JR, JK; writing—original draft, ZM, MB; writing—review and editing, AM, AMC, JR, JK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehmood, Z., Bilal, M., Munshi, A. et al. Image tampering detection using dynamic histogram equalization based LIOP features and novel scaled K-means + + clustering. Sci Rep 15, 18007 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01112-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01112-0