Abstract

Several new surgical techniques for managing refractory diabetic macular edema (DME) have demonstrated favorable short-term outcomes. However, no studies have reported the long-term outcomes of these treatments. This study aimed to evaluate the long-term outcomes of cystotomy for DME retrospectively. Twenty-seven patients (31 eyes; 16 male, 11 female) who underwent cystotomy for DME between January 2015 and April 2019, with a follow-up period of 3 years were included. Statistical analyses involved variables including age, sex, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), central macular thickness (CMT), number of treatments (anti-vascular endothelial growth factor, sub-Tenon injection of triamcinolone acetonide, direct photocoagulation for microaneurysms, vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling), number of clinic visits, and DME recurrence. The mean age was 67.2 ± 9.3 years. BCVA (logMAR) and CMT(µm) significantly improved from preoperatively to 3 years postoperatively (P < 0.001). Total treatments significantly decreased from the year before surgery to the third year after surgery (P < 0.001). The mean number of clinic visits significantly decreased from the year before surgery to the third year after surgery (P < 0.001). Fibrinogen clot removal was performed in 14 eyes. and DME recurrence occurred in 12 eyes. Cystotomy may be a viable treatment option for DME.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is intricately linked to increased vascular permeability, blood-retinal barrier disruption, retinal microaneurysms (MA) formation, and vitreoretinal traction. Abnormal expression of various cytokines, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), plays a critical role in these pathological processes.

Effective treatment for DME requires a comprehensive approach that addresses these underlying conditions. Current therapeutic strategies primarily involve anti-VEGF therapy, in combination with sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide administration (STTA), retinal photocoagulation, and pars plana vitrectomy (PPV)1,2,3,4. Although most cases of DME can be managed with these combined treatments, refractory cases that resist therapy have been reported5,6, posing a significant ongoing challenge.

Recently, new surgical techniques, including planned subretinal injection of balanced salt solution (BSS)7,8, cystotomy9,10, and fibrinogen clot removal11,12,13,14, have been attempted in managing refractory DME, with each demonstrating favorable short-term outcomes. However, no studies have reported the long-term outcomes of these treatments.

Therefore, this study aimed to report the 3-year postoperative outcomes of cystotomy and fibrinogen clot removal for DME.

Results

Table 1 shows the preoperative background of the patients. The participants included 27 cases with 31 eyes (16 males and 11 females) comprising six phakic and 25 pseudophakic eyes. The average age was 67.2 ± 9.3 years.

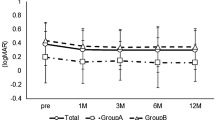

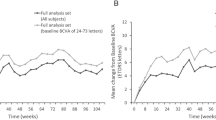

Analysis of all the cases revealed that average BCVA significantly improved and remained constant from 0.41 ± 0.29 preoperatively to 0.38 ± 0.28 at 1 month, 0.32 ± 0.24 at 3 months, 0.33 ± 0.26 at 6 months, 0.33 ± 0.23 at 1 year, 0.33 ± 0.26 at 2 years, and 0.32 ± 0.29 at 3 years postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, average CMT significantly improved and sustained from 514.2 ± 132.9 preoperatively to 322.2 ± 78.5 at 1 month, 317.1 ± 109.3 at 3 months, 323.4 ± 104.9 at 6 months, 320.7 ± 112.8 at 1 year, 285.3 ± 97.2 at 2 years, and 268.4 ± 75.3 at 3 years postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Fibrinogen clot removal was performed in 14 eyes (45.2%).The average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, photocoagulation for microaneurysm [MA-PC], PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.7 ± 2.3, 0.4 ± 0.7, 0.8 ± 0.4, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.5 ± 2.5 in the year before surgery and decreased to 0.5 ± 1.6, 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.5 ± 1.0, 0.1 ± 0.2, and 1.2 ± 2.0 in the first year after surgery; 0.3 ± 1.1, 0.1 ± 0.2, 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.1 ± 0.3, and 0.5 ± 1.5 in the second year after surgery; and 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.0 ± 0.2, 0.3 ± 0.7, 0.1 ± 0.2, and 0.5 ± 1.2 in the third year after surgery, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). The average number of visits significantly decreased from 14.5 ± 6.6 in the year before surgery to 8.5 ± 3.5, 5.2 ± 3.1, and 3.6 ± 2.8 in the first, second and third years after surgery, respectively (Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) over time for all cases. In all cases, BCVA (logMAR) improved significantly from 0.41 ± 0.29 preoperatively (pre) to 0.38 ± 0.28 at 1 month postoperatively (1 M), 0.32 ± 0.24 at 3 months (3 M), 0.33 ± 0.26 at 6 months (6 M), 0.33 ± 0.23 at 1 year (1Y), 0.33 ± 0.26 at 2 years (2Y), and 0.32 ± 0.29 at 3 years (3Y) postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

Central macular thickness (CMT) over time for all cases. In all cases, CMT (µm) improved significantly from 514.2 ± 132.9 preoperatively (pre) to 322.2 ± 78.5 at 1 month postoperatively (1 M), 317.1 ± 109.3 at 3 months (3 M), 323.4 ± 104.9 at 6 months (6 M), 320.7 ± 112.8 at 1 year (1Y), 285.3 ± 97.2 at 2 years (2Y) and 268.4 ± 75.3 at 3 years (3Y) postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

Treatment frequency over time for all cases. In all cases, the average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.7 ± 2.3, 0.4 ± 0.7, 0.8 ± 0.4, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.5 ± 2.5 in the year before surgery and decreased to 0.5 ± 1.6, 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.5 ± 1.0, 0.1 ± 0.2, and 1.2 ± 2.0 in the first year after surgery; 0.3 ± 1.1, 0.1 ± 0.2, 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.1 ± 0.3, and 0.5 ± 1.5 in the second year after surgery; and 0.1 ± 0.4, 0.0 ± 0.2, 0.3 ± 0.7, 0.1 ± 0.2, and 0.5 ± 1.2 in the third year after surgery, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001 ; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01). (VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, STTA sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide administration, MA-PC photocoagulation for microaneurysm, PPV pars plana vitrectomy)

Average number of clinic visits over time for all cases. In all cases, the average number of clinic visits significantly decreased from 14.5 ± 6.6 in the year before surgery to 8.5 ± 3.5 in the first year postoperatively, 5.2 ± 3.1 in the second year postoperatively, and 3.6 ± 2.8 in the third year postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

In this study, recurrence was defined as the reappearance of CME in optical coherence tomographic (OCT) findings. Additional treatment was administered to recurrent cases after consultation with the patient. Consequently, there were 12 eyes in the recurrence group and 19 eyes in the no recurrence group. Differences in sex, age, lens status, preoperative BCVA, preoperative CMT, fibrinogen clot removal, treatment frequency, or number of visits in the year before surgery between the two groups were not significant. In the recurrence group, BCVA was 0.41 ± 0.29 preoperatively, 0.38 ± 0.28 at 1 month, 0.32 ± 0.24 at 3 months, 0.33 ± 0.26 at 6 months, 0.33 ± 0.23 at 1 year, 0.33 ± 0.26 at 2 years, and 0.32 ± 0.29 at 3 years postoperatively, with no significant changes (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.78). In the no recurrence group, BCVA improved significantly from 0.38 ± 0.27 preoperatively to 0.35 ± 0.24 at 1 month, 0.28 ± 0.19 at 3 months, 0.26 ± 0.21 at 6 months, 0.28 ± 0.19 at 1 year, 0.26 ± 0.22 at 2 years, and 0.24 ± 0.24 at 3 years postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). CMT significantly improved and sustained in both the recurrence group (from 514.2 ± 132.9 preoperatively to 322.2 ± 78.5 at 1 month, 317.1 ± 109.4 at 3 months, 319.3 ± 105.6 at 6 months, 320.7 ± 112.8 at 1 year, 285.3 ± 97.2 at 2 years, and 268.4 ± 75.3 at 3 years; Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001) and no recurrence group (from 510.4 ± 121.2 preoperatively to 289.7 ± 54.8 at 1 month, 287.8 ± 88.2 at 3 months, 310.6 ± 103.8 at 6 months, 293.4 ± 83.4 at 1 year, 258.5 ± 65.0 at 2 years, and 263.8 ± 79.1 at 3 years; Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 6). The average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.8 ± 1.9, 0.5 ± 0.8, 0.9 ± 0.3, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.7 ± 1.9 in the year before surgery and decreased to 1.3 ± 2.5, 0.3 ± 0.7, 0.9 ± 1.4, 0.2 ± 0.4, and 2.7 ± 2.5 in the first year after surgery; 0.8 ± 1.7, 0.2 ± 0.4, 0.2 ± 0.6, 0.3 ± 0.5, and 1.4 ± 2.2 in the second year after surgery; and 0.3 ± 0.6, 0.1 ± 0.3, 0.6 ± 1.0, 0.2 ± 0.4, and 1.1 ± 1.7 in the third year after surgery, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) in the recurrence group (Fig. 7). In the no recurrence group, the average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.7 ± 2.6, 0.4 ± 0.6, 0.7 ± 0.5, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.3 ± 2.8 in the year before surgery, respectively, but no additional treatments were required in the 3 years after surgery (Fig. 7). The average number of visits significantly decreased in both the recurrence group (from 14.9 ± 7.2 in the year before surgery to 10.7 ± 4.1 in the first year after surgery, 6.8 ± 4.2 in the second year after surgery, 5.3 ± 3.9 in the third year after surgery; Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001) and no recurrence group (from 14.3 ± 6.4 in the year before surgery to 7.1 ± 2.1 in the first year after surgery, 4.2 ± 1.8 in the second year after surgery, 2.5 ± 0.9 in the third year after surgery; Kruskal-Wallis test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 8).

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) over time for recurrence and no recurrence groups. In the recurrence group, BCVA was 0.41 ± 0.29 preoperatively (pre), 0.38 ± 0.28 at 1 month (1 M), 0.32 ± 0.24 at 3 months (3 M), 0.33 ± 0.26 at 6 months (6 M), 0.33 ± 0.23 at 1 year (1Y), 0.33 ± 0.26 at 2 years (2Y), and 0.32 ± 0.29 at 3 years (3Y) postoperatively, with no significant changes (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.78). In the no recurrence group, BCVA improved significantly from 0.38 ± 0.27 preoperatively to 0.35 ± 0.24 at 1 M, 0.28 ± 0.19 at 3 M, 0.26 ± 0.21 at 6 M, 0.28 ± 0.19 at 1Y, 0.26 ± 0.22 at 2Y, and 0.24 ± 0.24 at 3Y postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

Central macular thickness (CMT) over time for recurrence and no recurrence groups. In the recurrence group, CMT (µm) improved significantly from 514.2 ± 132.9 preoperatively (pre) to 322.2 ± 78.5 at 1 month postoperatively (1 M), 317.1 ± 109.4 at 3 months (3 M), 319.3 ± 105.6 at 6 months (6 M), 320.7 ± 112.8 at 1 year (1Y), 285.3 ± 97.2 at 2 years (2Y), and 268.4 ± 75.3 at 3 years (3Y) postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01). In the no recurrence group, CMT improved significantly from 510.4 ± 121.2 preoperatively to 289.7 ± 54.8 at 1 M postoperatively, 287.8 ± 88.2 at 3 M, 310.6 ± 103.8 at 6 M, 293.4 ± 83.4 at 1Y, 258.5 ± 65.0 at 2Y, and 263.8 ± 79.1 at 3Y postoperatively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

Treatment frequency over time for recurrence and no recurrence groups. In the recurrence group, the average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.8 ± 1.9, 0.5 ± 0.8, 0.9 ± 0.3, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.7 ± 1.9 in the year before surgery and decreased to 1.3 ± 2.5, 0.3 ± 0.7, 0.9 ± 1.4, 0.2 ± 0.4, and 2.7 ± 2.5 in the first year after surgery; 0.8 ± 1.7, 0.2 ± 0.4, 0.2 ± 0.6, 0.3 ± 0.5, and 1.4 ± 2.2 in the second year after surgery; and 0.3 ± 0.6, 0.1 ± 0.3, 0.6 ± 1.0, 0.2 ± 0.4, and 1.1 ± 1.7 in the third year after surgery, respectively (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01). In the no recurrence group, the average number of anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, PPV, and total number of all treatments were 1.7 ± 2.6, 0.4 ± 0.6, 0.7 ± 0.5, 0.5 ± 0.5, and 3.3 ± 2.8 in the year before surgery, respectively, but no additional treatments were required in the 3 years after surgery. (VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor, STTA sub-Tenon triamcinolone acetonide administration, MA-PC photocoagulation for microaneurysm, PPV pars plana vitrectomy)

Average number of clinic visits over time for recurrence and no recurrence groups. In the recurrence group, the average number of clinic visits significantly decreased from 14.9 ± 7.2 in the year before surgery to 10.7 ± 4.1 in the first year after surgery, 6.8 ± 4.2 in the second year after surgery, and 5.3 ± 3.9 in the third year after surgery (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01). In the no recurrence group, the average number of clinic visits significantly decreased from 14.3 ± 6.4 in the year before surgery to 7.1 ± 2.1 in the first year after surgery, 4.2 ± 1.8 in the second year after surgery, and 2.5 ± 0.9 in the third year after surgery (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001; Dunn’s test, **P < 0.01).

Given that significant improvement in BCVA was observed in the no recurrence group but not in the recurrence group, logistic regression analysis was performed with recurrence as the dependent variable. However, no significant factors were identified (Table 2).

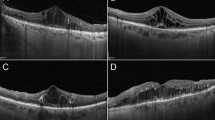

The surgical techniques for cystotomy and fibrinogen removal in a representative case from the no-recurrence group are demonstrated in Supplemental Video 1, while the time course of OCT and fundus findings for the same patient is shown in Fig. 9.

Course of optical coherence tomography and fundus findings in a representative case from the no recurrence group. A 71-year-old male. Despite undergoing three anti-VEGF therapy sessions, one MA-PC, and PPV with internal limiting membrane peeling for DME in the left eye, there was no improvement, so cystotomy was performed. Preoperative best-corrected decimal visual acuity was 0.4. OCT findings showed DME (A). At six months post-surgery, DME had resolved (B), and the best-corrected decimal visual acuity improved to 0.6. At one year post-surgery, there was no recurrence of DME (C), and the best-corrected decimal visual acuity remained at 0.6. Even at two years post-surgery, DME had not recurred (D), and the best-corrected decimal visual acuity improved to 0.7. At three years post-surgery, DME had not recurred (E), and the best-corrected decimal visual acuity improved to 1.0. During follow-up fundus photography, there was no occurrence of foveal chorioretinal atrophy attributable to this procedure (F) preoperative, (G) 6 months post-surgery, (H) one year post-surgery, (I) 2 years post-surgery, (J) 3 years post-surgery). (VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, MA-PC photocoagulation for microaneurysm, PPV pars plana vitrectomy, DME diabetic macular edema, OCT optical coherence tomography).

Discussion

Recently, the effectiveness of cystotomy for refractory CME, including DME, has garnered attention9,10,11,12,13,14. The initial report described this technique as an adjunctive procedure during primary PPV (without internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling) for 22 eyes with DME, resulting in improvement in 16 of 22 eyes (72.7%) and visual acuity improvement or maintenance in 20 of 22 eyes (90%)9. Asahina et al. reported significant visual acuity improvement and reduction in CMT at 6 months postoperatively in 20 eyes with DME (17 eyes underwent PPV with epiretinal membrane peeling, ILM peeling, and cystotomy, and 3 eyes underwent cystotomy alone)10. Furthermore, we have reported significant improvement in visual acuity, central retinal sensitivity, and CMT at 1 month postoperatively, which was maintained until 12 months in 30 eyes with refractory DME resistant to conventional treatments, including anti-VEGF therapy, STTA, MA-PC, and PPV with ILM peeling12. We also reported significant visual acuity improvement and CMT reduction at 1 month postoperatively and maintained until 12 months in patients who underwent this procedure as the primary treatment due to difficulty with continuous follow-up15. In the present study, significant CMT reduction at 1 month and significant visual acuity improvement at 3 months were observed; with these effects maintained for 3 yeats postoperatively suggesting that this procedure may be beneficial not only for refractory DME but also as an adjunctive treatment during PPV, potentially offering long-term therapeutic effects.

Notably, anti-VEGF therapy is undoubtedly the cornerstone of DME treatment. Large prospective studies have established strong evidence for its efficacy in improving visual acuity16. However, real-world retrospective studies suggest that the effectiveness of anti-VEGF therapy may be inferior to that reported in large prospective studies17,18,19,20. These findings imply that frequent intravitreal injections are essential for achieving reduction in macular edema and visual acuity improvement observed in these studies. Moreover, real-world retrospective studies have indicated that multiple induction treatments at the loading phase21, and the use of the Treat & Extend method during the maintenance phase22,23,24 are beneficial for maintaining improved visual acuity. However, both multiple induction treatments and the Treat & Extend method, where additional injections are administered before macular edema recurs, tend to result in a higher number of intravitreal injections compared with single-dose treatment and additional injections upon recurrence25,26. This suggests that achieving the full benefits of anti-VEGF therapy requires numerous intravitreal injections, which increases the burden of clinic visits, presenting a significant economic and physical burden to the patients27,28. Thus, while current DME treatment is largely based on multidisciplinary approaches centered around anti-VEGF therapy, the treatment of refractory cases and patients with difficulty in continuous follow-up remains a critical concern. The results of this study, showing a significant reduction in the number of treatments and visits postoperatively compared to preoperatively, suggest that cystotomy may be a viable option for reducing the economic and physical burden on patients. In contrast, recent reports suggest that many patients with DME are willing to accept increased economic and physical burdens from treatment to achieve better visual outcomes29,30. These findings indicate that while it is essential to avoid the indiscriminate continuation of anti-VEGF therapy, decisions regarding the introduction of PPV and cystotomy should be made in close consultation with the patient.

In this study, DME recurred in 12 of 31 eyes (38.8%) over the 3-year postoperative period, with no significant improvement in BCVA compared with preoperative levels. Recently, new-generation anti-VEGF drugs such as brolucizumab31 and faricimab32, which can extend the intravitreal injection interval to 12–16 weeks—potentially reducing the number of injections and visits—have been introduced. These findings suggest that considering the existence of anti-VEGF therapies that can improve visual acuity with fewer injections, the indiscriminate introduction of cystotomy should be approached with caution. Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that cystotomy was effective in preventing DME recurrence for 3 years postoperatively in 19 of 31 eyes (61.2%), with significant improvement in BCVA, suggesting that this procedure may be effective in a subset of patients. However, the factors contributing to recurrence could not be identified from the results of this study. In the future, by conducting more detailed investigations and identifying factors that contribute to recurrence, this surgical procedure may become a viable option for treating a subset of patients with DME in whom the procedure proves effective. However, even at this point, we believe that it can serve as a treatment option for refractory DME that resists existing treatments or for cases where patients do not wish to continue with current therapies.

There are several limitations to the interpretation of the results of this study. First, as the study design is retrospective, there are inherent limitations in accurately assessing causal relationships. Additionally, due to the small number of cases, careful consideration is required to determine whether the results of this study can be generalized. Going forward, it is necessary to conduct prospective studies with a larger sample size to improve the reliability of the research. Furthermore, by extending the follow-up period, it will be crucial to more thoroughly evaluate the long-term durability and efficacy of the treatment.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that cystotomy and fibrinogen clot removal for DME may be effective in improving and maintaining BCVA and CMT over a long-term period of three years. With further investigation into the factors contributing to recurrence, this procedure could be a potential treatment option for DME treatment in the appropriate patient population that reduces the physical and economic burden on patients.

Methods

In total, 31 eyes that underwent cystotomy for DME at the Department of Ophthalmology, Kobe University Hospital, and were followed up for 3 years postoperatively between January 2015 and April 2019 were included in this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kobe University Hospital (Approval no.: B240036). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the committee due to the retrospective observational design of this study. However, patients could withdraw consent and opt-out of this study at any time via the hospital homepage. The criteria for patient selection were as follows: (1) cases of DME with cystoid macular edema (CME) that showed no improvement despite treatment with anti-VEGF therapy (ranibizumab, 0.5 mg or aflibercept, 2 mg), STTA, MA-PC, or PPV; (2) cases of DME with CME where patients, regardless of treatment history with anti-VEGF therapy or STTA, preferred PPV owing to the need for frequent visits or economic burden and chose not to initiate or continue these treatments. The exclusion criteria included (1) cataract of Grade 3 or higher according to the Emery-Little classification, (2) coexisting glaucoma, (3) history of uveitis, and (4) history of surgery for other vitreoretinal diseases.

The variables extracted from medical records and retrospectively analyzed included sex, age, lens status (phakic/pseudophakic), BCVA, and CMT preoperatively, and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months postoperatively, fibrinogen clot extraction, Recurrence of CME; number of treatments (anti-VEGF, STTA, MA-PC, PPV) in the year before surgery; additional number of treatments in the first, second, and third years after surgery for recurrent cases; and number of visits in the year before surgery, first, second, and third years after surgery were also recorded. CMT was measured using OCT (Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany). BCVA was converted to logarithmic minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for statistical analysis. The number of visits was limited to those related to DME treatment.

Surgical technique

The surgery was performed under local anesthesia (2% lidocaine, sub-Tenon anesthesia). The Constellation Vision System (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was used for surgery, and a wide-angle non-contact observation system (Resight®; Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany) was utilized for intraocular observation. In cases without a history of cataract surgery, phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation were performed first. In cases without a history of PPV, vitrectomy and ILM peeling within a range of approximately 2 disc diameters centered on the fovea were performed using a 27-gauge system. Subsequently, cystotomy and fibrinogen clot removal were conducted following the methods previously described11,12. Briefly, the inner wall of the subfoveal cystoid space was opened using 27G MaxGrip forceps (Alcon Grieshaber AG, Schaffhausen, Switzerland). If an exposed fibrinogen clot was identified within the cystoid cavity11, it was directly grasped and removed using the same microforceps. In cases where the surgeon could not visually confirm the presence of a fibrinogen clot, no further intervention was performed within the cystoid space. No cases underwent fluid-air exchange or intravitreal injection of expansive gas at the end of the surgery.

Statistical analyses

An unpaired t-test was used for intergroup comparisons (recurrence/no recurrence) of age, preoperative BCVA, preoperative CMT, treatment frequency, and number of visits in the year before surgery. A chi-square test was used for intergroup comparisons of sex, lens status, and the fibrinogen clot removal. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for analyzing the variance in BCVA, CMT, treatment frequency, and number of visits preoperatively and postoperatively. Dunn’s test was used for post-hoc analysis. Logistic regression analysis was performed with recurrence as the dependent variable. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (IBM, version 24.0), with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from H. Imai, the corresponding author, on reasonable request.

References

Cheema, A. A. & Cheema, H. R. Diabetic macular edema management: a review of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapies. Cureus 16, e52676 (2024).

Prince, J., Kumar, D., Ghosh, A., Arevalo, J. F. & Zhang A. Y. Surgical management of diabetic macular edema. Curr. Diab Rep. 23, 119–125 (2023).

Salvetat, M. L. et al. The treatment of diabetic retinal edema with intravitreal steroids: how and when. J. Clin. Med. 13, 1327 (2024).

Tai, F. et al. Subthreshold compared with threshold macular photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmol. Retina. 8, 223–233 (2024).

Nguyen, Q. D. et al. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology 119, 789–801 (2012).

Grigorian, R., Bhagat, N., Lanzetta, P., Tutela, A. & Zarbin, M. Pars plana vitrectomy for refractory diabetic macular edema. Semin Ophthalmol. 18, 116–120 (2003).

Morizane, Y. et al. Planned foveal detachment technique for the resolution of diffuse diabetic macular edema. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 59, 279–287 (2015).

Toshima, S., Morizane, Y., Kimura, S. & Shiraga, F. Planned foveal detachment technique for the resolution of diabetic macular edema resistant to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Retina 39 (Suppl 1), S162–S168 (2019).

Tachi, N., Hashimoto, Y. & Ogino, N. Cystotomy for diabetic cystoid macular edema. Doc. Ophthalmol. 97, 459–463 (1999).

Asahina, Y. et al. Six-month postoperative outcomes of intraoperative OCT-guided surgical cystotomy for refractory cystoid macular edema in diabetic eyes. Clin. Ophthalmol. 11, 2099–2105 (2017).

Imai, H., Otsuka, K., Tetsumoto, A., Miki, A. & Nakamura, M. Effectiveness of En bloc removal of fibrinogen-rich component of cystoid lesion for the treatment of cystoid macular edema. Retina 40, 154–159 (2020).

Imai, H. et al. Long-term effect of cystotomy with or without the fibrinogen clot removal for refractory cystoid macular edema secondary to diabetic retinopathy. Retina 41, 844–851 (2021).

Yamada, H. et al. Cystotomy with or without fibrinogen clot removal for refractory cystoid macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Sci. Rep. 11, 8460 (2021).

Maki, H. et al. The long-term effect of cystotomy with fibrinogen clot removal for a cystoid macular edema secondary to idiopathic macular telangiectasia type 1: a case report. Retin Cases Brief. Rep. 17, 101–104 (2023).

Iwane, Y. et al. A case of diabetic maculopathy successfully treated with Pars plana vitrectomy with cystotomy and subretinal hard exudate extraction from an intentional macular hole. J. Eye. 40, 95–100 (2023).

Dugel, P. U. et al. Baseline visual acuity strongly predicts visual acuity gain in patients with diabetic macular edema following anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment across trials. Clin. Ophthalmol. 10, 1103–1110 (2016).

Ciulla, T. A., Bracha, P., Pollack, J. & Williams, D. F. Real-world outcomes of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in diabetic macular edema in the united States. Ophthalmol. Retina. 2, 1179–1187 (2018).

Shimura, M. et al. Real-world management of treatment-naïve diabetic macular oedema in Japan: two-year visual outcomes with and without anti-VEGF therapy in the STREAT-DME study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 104, 1209–1215 (2020).

Ciulla, T. A., Pollack, J. S. & Williams, D. F. Visual acuity outcomes and anti-VEGF therapy intensity in diabetic macular oedema: a real-world analysis of 28 658 patient eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105, 216–221 (2021).

Sakamoto, T. et al. Impact on visual acuity and psychological outcomes of Ranibizumab and subsequent treatment for diabetic macular oedema in Japan (mercury). Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260, 477–487 (2022).

Mitchell, P. et al. Effectiveness and safety of Ranibizumab 0.5 mg in treatment-naïve patients with diabetic macular edema: results from the real-world global LUMINOUS study. PLOS ONE. 15, e0233595 (2020).

Shimura, M. et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in diabetic macular edema: 2-year results from the Japan subgroup of the phase 3 YOSEMITE trial. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. Online. ahead of print (2024).

Hirano, T. et al. Outcomes of a 2-year treat-and-extend regimen with Aflibercept for diabetic macular edema. Sci. Rep. 11, 4488 (2021).

Hirano, T. et al. Treat-and-extend therapy with Aflibercept for diabetic macular edema: a prospective clinical trial. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 65, 354–362 (2021).

Sarohia, G. S. et al. Treat-and-extend versus alternate dosing strategies with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents to treat center involving diabetic macular edema: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 2,346 eyes. Surv. Ophthalmol. 67, 1346–1363 (2022).

Lai, T. T. et al. Treat-and-extend vs. pro re Nata regimen of Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema-A two-year matched comparative study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 781421 (2021).

Sugimoto, M. et al. Clinical preferences and trends of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatments for diabetic macular edema in Japan. J. Diabetes Investig. 10, 475–483 (2019).

Hahn, P. & Garg, S. Global trends in retina survey (American society of retina specialists). https://www.asrs.org/sections/international/global-trends-in-retina

Bhagat, D. et al. Patient preferences associated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies for neovascular age-related macular degeneration and diabetic macular edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 14, 2975–2982 (2020).

Mason, L., Crosson, J. N., Mason, J. O. 3 & McGwin, G. rd Jr. Patient preferences with regard to laser versus intravitreal injections in the treatment of diabetic macular edema. J. Ophthalmol. 7398470 (2017).

Brown, D. M. et al. Kestrel and KITE: 52-week results from two phase III pivotal trials of Brolucizumab for diabetic macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 238, 157–172 (2022).

Wykoff, C. C. et al. Efficacy, durability, and safety of intravitreal faricimab with extended dosing up to every 16 weeks in patients with diabetic macular oedema (YOSEMITE and RHINE): two randomised, double-masked, phase 3 trials. Lancet 399, 741–755 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S. and H. Y. acquired the data.H. I. and H. Y. analyzed and interpreted the data. H. I. and H. Y. prepared all the figures and tables.H. I. wrote the main manuscript text.W. M., A. M., S. K., and M. N. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.All the authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, H., Imai, H., Sotani, Y. et al. Three-year outcomes of cystotomy and fibrinogen clot removal for diabetic macular edema with subfoveal cystoid macular edema. Sci Rep 15, 16019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01197-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01197-7