Abstract

This study examines the voltage stability challenge in hybrid DC microgrids that power Constant Power Loads (CPLs). Due to uncertainties in both supply and demand, traditional linear controllers are often inadequate, leading to inevitable voltage oscillations under uncertain conditions. This article introduces a robust passivity-based control (PBC) approach aimed at reducing instability issues, while considering the dynamic behaviour of the hybrid DC microgrid in the presence of CPL. The main objective is to achieve large-signal stabilization of the output voltage of a CPL powered by a hybrid DC microgrid through a series-damped passivity-based control (PBC) scheme, while considering the dynamic performance of renewable energy sources and loads. DC microgrids, which include parallel source subsystems, present additional challenges in analysing the nonlinear stability of the entire system, often requiring complex dynamical equations. Therefore, the stability analysis, based on the passivity property, can be easily conducted for each subsystem individually within the hybrid DC microgrid. The proposed controller prevails over other non-linear controllers because of its accuracy, reliability, and simplicity, while also exhibiting a more robust response compared to the control techniques previously suggested. MATLAB simulations and experimental results are provided to validate the robustness of the proposed controller.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy demands are increasing drastically due to the growing population and technological advancements. However, a large consumption of fossil fuels will lead to carbon emissions. Consequently, environmental pollution is becoming more serious. To avoid pollution, other energy sources have recently gained more attention than fossil fuels. As a result, there is growing adoption of sustainable energy sources such as wind, tidal, solar, geothermal, and biomass. Using RES with power electronics converters, a new structure called a microgrid has been created. Basically, there are two microgrids, such as AC microgrids and DC microgrids1. DC microgrids are preferable because of their high robustness, efficiency, and affinity for distributed generation sources, including solar photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, fuel cells, and battery storage systems.

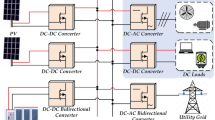

Constant impedance load (CIL) and constant power loads are two primary types of load accessible in DC microgrids. The fundamental concept of a hybrid DC microgrid is demonstrated in Fig. 1. When closely regulated, power electronics converters in technically advanced systems behave as CPL2. So, CPL has the characteristic of constant power consumption from the input bus.

The most recent topics of research are related to CPL3,4 because power electronics have a substantial impact on the stability and dependability of DC microgrids. A CPL is demonstrated by a DC–AC inverter, which precisely powers and regulates the speed of an electric motor. And a DC–DC converter delivers power to an electrical load and precisely controls its voltage when the load exhibits a direct voltage-current relationship. A resistor, which has a proportional dependence between current and voltage, is the most basic type of these loads.

CPLs consist of strictly controlled Point-of-Load converters that continuously draw power from the DC source and exhibit the characteristic of negative incremental input impedance. As a result, the supplied voltage (or current) will drop when the CPL’s current (or voltage) increases. Therefore, CPLs are speculated to be the primary cause of voltage instability in the DC microgrid3. The system is weakly damped and exhibits lossless energy dissipation at the input terminals of the CPL due to its instability. The negative incremental impedance characteristic inherent in the CPL prevents the system from returning to equilibrium when its supply voltage fails or when there is a voltage drop across the input of the CPL. As a result, oscillations lead to limit-cycle behavior in voltage across the DC bus and create an unstable equilibrium point. Consequently, undesirable characteristics such as increased stress on the source power converter switches and the occurrence of limit cycles arise. This stress shortens the lifetime of the switching components and may even cause their failure. Furthermore, constant power loads may result in a blackout or brownout. Therefore, addressing the effects of CPLs is one of the most challenging problems in managing DC microgrids.

To enhance the voltage stability of a hybrid DC microgrid5 due to CPL, a control strategy is required. Scientific research offers several nonlinear control techniques6 to address the unstable behavior and destructive effects of CPLs because of their nonlinearity structure7,8,9,10. A linearization technique using a small-signal model was used in most of the earlier research11,12. In13 and14, active damping approaches such as a linear technique for stabilizing a CPL-integrated dc MG were presented. With these techniques, the control loop is shaped by adding virtual impedance to the system rather than actual passive components. Only a limited neighbourhood around the steady-state equilibrium point receives accurate control performance from this method. So, the system stability can be quickly challenged when large-signal disruptions occur, such as line variation (RES changes) and high-load transients. Several nonlinear control approaches are also already utilized in different papers, such as the sliding mode controller15,16,17, model predictive controller18,19, fuzzy logic controller20, feedback linearization method21,22,23,24,25, passivity-based controller26,27, backstepping controller28,29,30 and synergetic controller31,32. To achieve better system dynamic capabilities and regulate shunt-connected buck converters, the synergetic control method was suggested32,33. Although there is a noticeable decline in the performance of the centralized synergetic control, the voltage transients behave in a manner similar to the load step. This behavior results from the fact that system fluctuations have a greater impact on this control. Nonlinear Disturbance Observer (NDO) with back-stepping control technique has been designed to regulate the CPL fed through the boost converter15. This method guarantees stability even when the CPL varies widely. However, this controller is highly sensitive to parameter variations and disturbances, with larger load power step changes leading to a more significant dip in the output voltage34,35. A concept for precise linearization based on differential geometry theory and an analysis of a DC microgrid’s stability utilizing a DC–DC bidirectional converter are offered in36. As it is a high-gain control method, the system’s resilience to measurement noise will decline. To minimize the multi-converter uncertainty in DC distribution systems caused by CPL,16 adopted the SMC technique. Problems with chattering will result from varying switching frequency requirements. If an output filter capacitor current measurement is required, the capacitor and current sensor need to be linked in series. This increases the costs and causes a rise in equivalent series resistance (ESR), which mitigates the impact of ripple on the filter and raises the impedance of output terminals37,38,39,40,41. In18, a model predictive controller (MPC) was proposed. The online computational overhead of MPC limits its practical application and presents a significant drawback for its use42,43,44,45,46,47. A fuzzy logic controller was suggested for the buck converter in20, but no evidence of stability was provided.

Recently, PBC strategies have gained more attention in CPL-powered DC microgrids. By using the PBC controller, it is feasible to accomplish the global stabilizing requirement for DC microgrid26. PBC relied on the energy conservation concept. According to this principle, the energy supplied equals the sum of the energy released and the energy retained. It was proposed by Ortega et al.48. PBC is straightforward systematic modeling, so it makes more practical and successful than other nonlinear control strategies and marking it as the preferred method among various controllers27. If the system is not passive, the dissipation of energy in it will be modified by the PBC, which will then reduce the oscillation and make it passive by injecting a virtual impedance. The majority of research work focuses on DC–DC buck converters20,21,32,49 and DC–DC boost converters15,18,19,27,50 that feed CPL. However, the dc–dc boost converter presents significant challenges due to its non-minimum phase characteristics.

This article focuses on the application of PBC theory within hybrid DC microgrid systems that integrate sustainable energy sources, like solar PV panels and wind turbines. In real-scenario, DC microgrids are predominantly supplied by both wind turbines and PV panels. And this research aims to extend this application to a hybrid microgrid setting, thereby addressing new challenges and offering insights into the integration of renewable energy sources and CPLs. In general, DC microgrids consist of parallel source subsystems that supply other parallel load subsystems through DC–DC power converters. Each converter has its own local feedback control system with distinct control parameters and circuit characteristics. This introduces additional challenges when analysing the nonlinear stability of the hybrid DC microgrid, often requiring complex dynamic equations. Stability analysis based on passivity properties can be performed separately for each subsystem, as the goal of this research is to address the stability issues caused by Constant Power Loads (CPLs). This can be achieved by ensuring each subsystem’s energy is made strictly passive through a passivity-based feedback controller (PBC). A key advantage of PBC is a system that is created by group of passive subsystems is considered passive (stable) when they are linked together via feedback or parallel connections. This means the energy supplied by each source subsystem is dissipated by the corresponding load subsystem, ensuring that the overall energy balance of the DC microgrid remains positive. The dynamic behaviour of CPLs and the fluctuating nature of renewable energy output offers distinct challenges and opportunities. Consequently, we have developed a control algorithm that integrates a parallel connected DC–DC boost converter into the hybrid DC microgrid system. Additionally, the effectiveness of this novel control algorithm for the CPL supplied through the hybrid DC microgrid has been validated and discussed. Proposed controller can perform better performance than other nonlinear controller because an adequate theoretical approach to implement the idea of energy dissipation. Through virtual damping injection, system can damp out its oscillation by reshaping the energy dissipation. Another feature of PBC controller modelled with Euler–Lagrange equations51 is its effectiveness in hybrid system where more than two power sources such as wind, solar and fuel cell has connected.

This research work mainly focuses on non-linear controllers, such as passivity-based controllers, for the hybrid DC microgrid. The following list outlines the significance of the paper.

-

Design and implement PBC control techniques tailored specifically for DC microgrids with CPL’s to effectively enhance voltage stability under varying line and load conditions.

-

Analyze the performance of linear and nonlinear controllers for voltage stabilization of a DC microgrid with CPL.

-

Implement the PBC technique in a real-time HIL environment to showcase the effectiveness of the system.

This article’s overview is as follows: The modeling of CPL powered by a DC microgrid is described in section “Modelling of CPL powered by DC microgrid”. Stability analysis of CPL powered by DC microgrids is mentioned in section “Stability analysis of CPL powered with DC microgrid”. The fundamentals of PBC controllers are discussed in section “Passivity based controller”, while the application of PBC controllers in hybrid DC microgrids is covered in section “PBC controller for hybrid dc microgrid”. Results and discussion are provided in section “Result and discussion” and section “Conclusion” conveys the conclusions of the paper.

Modelling of CPL powered by DC microgrid

The DC–DC boost converter, which powers a CPL is illustrated in Fig. 2. This schematic diagram highlights the behaviour of the CPL load fed by Microgrid (Here it is considered as DC source). But in actual scenario there will be multiple input (like wind, solar and battery) is represented in section “PBC controller for hybrid dc microgrid”. Parameters of model has the following specifications: E, C, and L indicate the supply voltage, capacitor value, and inductor value of the circuit accordingly. Where the duty ratio, voltage over the DC link, and current passing through the inductor are represented by \(\mu\), \(V_0\), and \(I_L\).

It is considered that system operates in mode of continuous conduction. Dynamic model representations of the system are

\(V_0\), and \(I_L\) are considered state variables. But the presence of CPL creates a term in the dynamic equation such as \(P_{CPL}\)/\(V_0\) that creates non-linearity in the system. So, from this dynamic equation, the nonlinear characteristics of the system can be analyzed due to CPL. The characteristics of CPL can be easily analyzed from Fig. 3 (nonlinear characteristics). To maintain constant power across the load during load changes, CPL tries to adjust the terminal voltage. This leads to negative incremental impedance. With the negative incremental input impedance of the CPL, dV/dI exceeds zero. The \(i_0-v_0\) characteristics of the CPL and CIL in open-loop mode is shown in Fig. 3. During a stable region, a conventional control is required to achieve a steady-state DC bus voltage. If \(v_0 > V_0\), then the system is in a stable region. But when \(v_0 < V_0\), the system is in an unstable region. If a system has negative incremental impedance, then during the disturbance and uncertainty, the operating point moves because the equilibrium point is unstable.

\(i_0-v_0\) open-loop characteristics of the CPL and CIL27.

Stability analysis of CPL powered with DC microgrid

If the CIL in a DC microgrid is less than that in a CPL, then the voltage range of the system will vary widely. So, when the incremental input impedance is negative, it leads to oscillations. Rather than attenuating oscillations, negative incremental impedance causes them to intensify. So, stability analysis of CPL powered with DC microgrid is more important. To understand the stability issue due to presence of CPL in DC microgrid, a detailed analysis has been presented in this section “Stability analysis of CPL powered with DC microgrid”. Therefore, an open-loop analysis and a study to obtain the system’s characteristics have been conducted based on the basic configuration depicted in Fig. 2. Where supply voltage, 380V is fed to CPL, 22 KW through DC–DC boost converter with inductance, 9mH and capacitance, 1mF where voltage across DC link is 750V.

Steady state analysis of the system

An open-loop analysis is performed on the system shown in Fig. 2 to verify the stability of CPL when powered by a DC microgrid. Mainly, the step response and root locus of the system were determined by using the dynamic equation mentioned in (1). Figures 4 and 5 represent the step response and root locus of the studied system. From the step response, the system is not settled down at any time, and the final value of the system is infinity. And from the root locus, the system’s two poles are situated on the RHP (right hand side of plane).The dynamic response of the DC bus voltage in a closed-loop system is demonstrated Fig. 6. The state variables exhibit nonlinear behavior, such as limit cycles, which lead to an unstable equilibrium point due to the presence of the CPL. So, it is concluded that the given system is unstable.

Characteristics of the CPL powered DC microgrid

A CPL-powered boost power converter in a hybrid DC microgrid is the focus of this article. Whenever CPL is available in the DC microgrid, the chances of the system being unstable are high. The main cause is the negative incremental instability characteristics of CPL. This behavior is reflected in the following characteristics: In the CPL-powered DC microgrid, adding a load results in an increase in current. To maintain constant power, the voltage must change. This effect on the CPL is illustrated in Fig. 7. Therefore, based on this characteristic, it can be concluded that the incremental impedance will be negative. Figure 8 represents the voltage variation during load changes in the CPL-powered DC microgrid without any controller. And it is emphasizing the impact of CPL characteristics and the open-loop nature of the system’s performance. However, with the PBC controller, a CPL-powered DC microgrid system can achieve a stabilized DC bus voltage, as shown in Figs. 9 and 10.

Passivity based controller

In48, Ortega et al. introduced the PBC as a control structure that employs the passivity concept to stabilize the system. Energy conservation forms the foundation of this controller design. It consists of two stages: an energy shaping stage, where the total energy in the system is modified, and a damping injection stage, which ensures the required dissipation for achieving asymptotic stability. The PBC controller works by stabilizing the state of the system while preserving energy, achieved through the reshaping of the system’s energy through the injection of virtual damping resistances in the control action. Two concepts were used to develop the PBC, such as the Euler–Lagrange PBC (EL-PBC)52 and the Port-Controlled Hamiltonian PBC (PCH-PBC)52.

Port controlled Hamiltonian (PCH) model

The mathematical illustration of a nonlinear system is,

The PCH model of the design is presented by

Where \(H\left( z\right)\) is the function of energy, \(J_d = -{J_d}^T\) is known as matrix for interconnection, and \(R_d = {R_d}^T\) is the damping matrix. Control signal obtained through PCH method for the dynamic equation (1) is,

The damping factor, represented by R, is set to \(1\times 10^6\). The controller is designed to inhibit any rise in the system’s energy function. Through energy damping injection, the control aim is to stabilize the system by creating an energy storage function that reaches its minimum at the desired equilibrium point. These parameters are chosen within the permissible range for the damping injection term to ensure effective system stability.

Euler–Lagrange model

The model can be represented using the EL method as detailed below:

where J = −\(J^T\) represents the matrix for interconnection, R and \(\tau\) are damping injection matrix and the matrix including the supply voltages, and \(H_f\) is the function of energy (positive definite diagonal matrix).

Control signal obtained through Euler–Lagrange method for the dynamic equation (1) is,

Where R is damping factor,0.5

Figures 11 and 12 show the characteristics of the DC microgrid supplying the CPL, as illustrated in Fig. 2, using the EL method and PCH method. Comparisons between both controllers have been tabulated in Table 1. From the table, EL-PBC will reach the steady state more quickly compared to PCH-PBC. When compared to PCH-PCB53, EL-PBC54 exhibits less overshoot and a shorter settling period.

PBC controller for hybrid dc microgrid

Consider a system that consists of a Constant Voltage Load(CVL)(\(V\propto I\)) and a CPL (\(V \propto \frac{1}{I}\)).Purely resistive loads, which require a constant voltage for their operation, classify as CVLs. Where \(P_R\) represents CVL and \(P_{CPL}\) represents the CPL. So, when \(P_R > P_{CPL}\), the system will be stable because it is in passive mode. But when \(P_R < P_{CPL}\), negative incremental impedance characteristics will exist, so the system becomes unstable. It is evident from the system’s dynamic activity that a system with different loads, such as CPL and CVL, eventually be able to disperse a significant amount of energy and become stable (passive). Through the control action, virtual dampening resistances can be introduced, to reconfigure the system’s energy to stabilize the states without energy loss.

PBC controller design

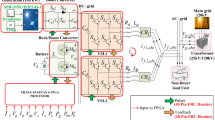

The main objective is to develop and deploy a controller for hybrid DC microgrid utilizing the PBC technique. To avoid the fluctuations and impact of unidentified dynamics, this technique is applied by adding series damping. Here, the simplified structure of the controller is utilized because control strategies can identify a distinct physical structure. This method has several benefits, including governing equations, simplicity in application, and resistance to model uncertainties. The primary constraint of the suggested control algorithm is its need for certain simplifications, which are suitable for low-speed applications such as traction and wind turbines. Figure 13 represents the hybrid DC microgrid with CPL. Here two supply sources such as solar and wind turbine are considered. Then the supply voltages of these two sources are denoted as \(E_1\) and \(E_2\). A significant feature of the PBC is a system which will be stable (Passive), if the system consist of two individual subsystem, and they have connected either in parallel or feedback26. This suggests that the other load subsystem would have squandered the energy given by each source subsystem. In this approach, the total energy balance of the DC micro-grid is consistently positive. The following dynamic expression can be used to depict a hybrid DC microgrid:

Where \(C_{eq}=C_1+C_2\),52 explains different concepts for PBC, such as PCH PBC and EL PBC. To achieve the stability of the system during uncertainty and line/load variation, the design of the PBC method using the theory of EL systems is explained in this article. The EL-PBC has more steady state performance than PCH-PBC. Consequently, mathematical modelling of the DC microgrid fed to CPL is determined using Euler–Lagrange approach. Mainly, there are two steps for PBC, such as energy function formation and damping injection. The EL systems can be used to define the whole energy-conserving dynamical system with independent storage parts by designating the duty cycles as the control inputs \(\mu _1\) and \(\mu _2\) of two switches, as shown in Fig. 1326.

Where the energy storage function is represented in matrix form \(H_f\), the vector of system states is Z, the vector consists of voltage sources, which represents E, J is the interconnection matrix, \(J^T =-J\), which accounts for the system energy exchange, and the dissipation matrix represents \(R_e\left( z\right)\). The state vector can be expressed as:

Stability conditions for closed loop system

It is feasible to define a function of energy storage with an optimal value at the intended point of equilibrium, where the control purpose of the energy damping injection is to stabilize the system. The method used in this paper is compared with the Interconnected and Damping Assignment PBC (IDA-PBC), and the energy storage function is initially chosen here. Therefore, it is feasible to design a controller that inhibits the system’s energy function from rising. Through this strategy, the passivity system improved, and it ensured the system’s stability. While using \(\tilde{Z}=Z - Z_d\) as the error variable in (11),

where \(Z_d\) is the set point of the system.

The convergence to equilibrium is accelerated by the inclusion of a further virtual dampening term, \(R_d\tilde{Z}\), on both sides of (13).

Where

After the impedance matrix \(R_d\) is introduced, the system becomes stable (passive), which is compatible with the Lyapunov concept. To address this instability issue caused by CPL, the control action can be applied in terms of the precise virtual damping resistances. This changes the boost power converter circuit, which is represented in Fig. 14 and consists of a parallel resistance \(R_3\) across the capacitor circuit and a series resistance \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) with the inductor circuit.

As time goes to infinity, the left portion of (15) approaches asymptotically zero, with \(\tilde{Z}=0\) serving as the global stable equilibrium point.

The stability theorem of Lyapunov for nonlinear systems is used to analyze the stability of the PBC approach. The energy storage function \(H_t\left( z\right)\) can be represented by using the positive definite matrix \(H_f\).

The derivative function of the energy stored is,

In (18), able to be written as,

Where \(J=-{J^T}\), so J is a skew symmetric matrix, then the term \({\tilde{Z}}^T J \tilde{Z}\) is zero. So (22) becomes,

From (23), it is clear that the system is stable since the energy storage function is changing at a slower rate over time. Therefore, the dynamics of energy (23) approach zero and provide a solution that is asymptotically stable, independent of the value of \(\mu _1\) and \(\mu _2\).

In stable conditions, side on the right of (15) ought to be equivalent to zero in order to accomplish damping injection and energy structuring, i.e.

By deconstructing the matrices of (24) can be written as,

The PBC controller design is mainly accomplished by incorporating the damping injection with the energy shaping stage. So, energy in the system becomes passive. The PBC controller helps to dampen and attenuate voltage oscillations in the DC bus when CPL is involved. In (25)–(27) explains the dynamic characteristics of a passivity-based control technique. Thus, the control signal can be obtained by solving equations (25)–(27), with the consideration that the system should reach the reference voltage with minimal ripples, thereby ensuring stability. The condition to get the desired output as (\(Z_{1d},Z_{2d},Z_{3d}\)) becomes (\(I_1, I_2, V_0\)), and the state variable’s transient dynamics (\(\dot{Z_{1d}}\), \(\dot{Z_{2d}}\), \(\dot{Z_{3d}}\)) should be zero. So, it can be represented as,

Here, it is assumed that the fixed reference inductor currents are calculated based on load sharing. Where \(R_1, R_2\) and \(R_3\) are the virtual damping impacts on the continuous power load. The only restriction placed on the choice of \(R_1, R_2\) and \(R_3\) by PBC design is that they should be positive. So, the damping resistance can therefore be selected in accordance with conventional and established procedures. So that the controller is reliable and unwanted effects are avoided.

In (28) and (29) explains the control action given by the PBC controller. Here, control signals are generated from the reference inductor currents. But the reference inductor current can be calculated from the DC bus voltage(\(V_d\)). Figure 15 represents the PBC control approach, where the outer loop calculate the reference for current through inductor(\(I_1\) and \(I_2\)) from the voltage error signal (where \(V_d\) is the actual DC bus voltage and \(V_0\) is the reference DC bus voltage). The inner current loop determines the switching signals for the two converters from the inductor current error signal(where \(i_1\) and \(i_2\) are actual inductor currents and \(I_1\) and \(I_2\) are reference inductor currents). Therefore, the DC bus voltage in a hybrid DC microgrid can be effectively regulated using PBC, ensuring that the parallel-connected non-ideal converters share the same amount of current.

Result and discussion

The simulations were performed on MATLAB/Simulink to evaluate the viability of the outlined strategy. The variables listed in Table 2 are utilized to model the suggested controller for boost power converter feeding CPL. Utilizing the simulation results, the efficacy of these control strategies for various disturbance types is investigated. The model of CPL that is used for the simulation is presented in Fig. 16. Modeling CPL as a controlled current source is possible. Here, the control signal is obtained from the \(I_{cref}\). Therefore, this load always maintains constant power. The PBC gains (damping resistance) are \(R_1=R_2=1\times {10^6}\) and \(R_3=0.08.\) To ensure dissipation of energy to the dynamics of limit-cycle and trajectory convergence to the intended equilibrium, the PBC gains have been altered.

\(R_1\) and \(R_2\), which are series with the inductor, should have a larger value to restrict inductor current ripples and for better energy dissipation. But the tiny value of the virtual resistance, which is parallel to capacitor \(R_3\), ensures that energy is dispersed across the circuits and helps to reduce output voltage ripples.

System behavior during load variation

As illustrated in Fig. 17, the value of the \(R_3\) has been adopted with distinct values to examine the control performance of PBC from a different vantage point. This analysis helps to understand controller performance when the damping resistance is changed. It is evident that a quick reaction in capacitor voltage can be obtained when the \(R_3\) value decreases. So, a lesser value of \(R_3\) provides the fastest response of the system to reach the steady-state value of the DC bus voltage. A comparison for different damping resistances \(R_3\) has been performed at the same time scale to compare the system behavior. PBC is helping to ensure the stabilized voltage during load changes from 5 to 6 KW at 5s. During load changes, the characteristics of current through inductors(\(I_1\) and \(I_2\)) and voltage across DC bus(\(V_d\)) are shown in Fig. 18. When CPL deviations occur, the fastest performance recovery and the most dependable control dynamic are provided by the PBC. The CPL is initially adopted at 5 kW, and at time t =5 s, it is modified to 6 KW. It is evident that the suggested controller provides consistent regulatory behavior regardless of changes in CPL. Furthermore, specifically predicted power converges to actual power.

System behavior during supply variation

This section features PBC’s performance through disturbance addition during input voltage variation is validated. Thus, the dynamic response of the boost power converter and current through the inductor when the input voltage is varied at 3s and 8s has been analyzed. Here at 8s, the input from the solar panel is varied because of the change in irradiance from 1000 to 800 w/m2 as demonstrated in Fig. 19. So, from Fig. 19, it can be observed the variation of supply from the PV solar panel. It is assumed that there is no dynamic change in irradiance and operating temperature of the PV panel, similar to the real-world scenario. And at 3s, the input from the wind turbine has changed due to variation in wind speed as shown in Fig. 20. However, with the suggested controller, the dc-bus voltage stays at its steady state value even at wide input voltages. Figure 21 represents the characteristics of current through inductors \((I_1\; {{and}}\; I_2)\), voltage across DC bus \((V_d)\), and estimated power of the CPL \((P_{CPL})\) of PBC during line variation at 3s and 8s. In these characteristics, observations have been made regarding the variation of inductor currents due to changes in supply. These supply variations cause changes in the input voltage, which in turn affect the inductor currents connected to these supplies. As a result, the inductor currents vary in response to the changes in input voltage. The addition of the PBC controller results in strictly controlled output voltage throughout fluctuations in input voltage. The DC bus voltage has small dynamic changes at 3s and 8s due to the effect of variation in supply. However, the PBC controller regulates the DC bus voltage at its rated value, such as 500V. As the load is constant power load without any dynamic change, at this condition the value of CPL is maintained as constant. Due to these variations in supply, the given load can be balanced. However, for more dynamic variation in the supply, the load can be balanced once the MPPT algorithm is enabled. So, future work can focus on the MPPT algorithm incorporated with the proposed controller.

Comparison between linear and nonlinear controller

To evaluate the control effectiveness of linear and nonlinear controllers for the CPL powered by a boost power converter in a DC microgrid, a simulation study has been performed. In this context, the PBC controller is compared with both a linear controller, such as the PI controller, and nonlinear controllers like the Sliding Mode Controller (SMC) and Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC). This comparative analysis highlights the need for an effective controller to achieve stability in a CPL fed by a DC microgrid during uncertainty. The variables listed in section “Stability analysis of CPL powered with DC microgrid” are used to model the proposed controller for the boost power converter feeding CPL. Even though the proposed controller is for a hybrid DC microgrid, this controller can effectively maintain the stability of the DC microgrid as well. For the comparison of the proposed controller with other linear and nonlinear controllers, a basic structure of the DC microgrid is used. The proposed controller, linear controller, and nonlinear controller have been used to regulate the DC bus voltage of system, where the DC bus voltage is 750V. Figure 22 represents a comparative analysis of the PI and PBC controllers at load variation. To understand the effectiveness of nonlinear controller with linear controller, a classical PI approach is used. The discrepancy between the desired voltage and the voltage across DC bus is input to the PI controller to attain the desired voltage across DC bus. The gain used for the PI controller are \(K_p = 0.01\) and \(K_i = 66.3649\). The PI controller exhibits a limit cycle in the DC bus voltage. So, system stability during load variation cannot be restored by using a linear controller11. However, with a nonlinear controller, the system can be stabilized regardless of demand variations. Figure 23 represents the comparison between PBC with different controllers. In times of uncertainty, the PBC outperforms all other controllers by effectively maintaining the stability of the system. Table 3 represents the comparison of transient characteristics of different control strategies. With regard to rise time, overshoot, settling time, and steady state errors, the recommended controller has been observed to perform more effectively like other controller FLC20 and SMC17. The comparative performances of the PBC algorithm, SMC, and FLC, including metrics such as standard deviation and performance functions like MSE, are summarized in the Table 3. The analysis indicates that the proposed control algorithm demonstrates superior robustness in performance when compared to other nonlinear controllers. However, in terms of control performance, PBC ensures stability in nonlinear systems by maintaining passivity, with control actions designed to balance energy, thereby improving energy efficiency. It has simple design procedure as PBC relies on the passivity property. In contrast, SMC involves complex mathematical design for the sliding surface and switching control law, and it suffers from chattering due to its switching control action. FLC, on the other hand, requires careful tuning of fuzzy membership functions and rule bases, making its performance less predictable and potentially suboptimal in some cases.

Experiment outcomes

An experimental setup within a real-time Hardware-in-the-Loop environment has been established to assess the effectiveness of the proposed PBC strategy. The hardware setup is depicted in the block diagram shown in Fig. 24. To verify the robustness of the proposed controller during uncertainty, the experimental setup mentioned in Fig. 24 has been used. In the setup, the focus of the analysis is highlighted in the red-colored block, which mainly indicates the isolated hybrid DC microgrid. In this setup, the supply is given through multiple sources such as the solar PV panel, wind turbine, and battery, where the DC bus is powered by the solar PV through a boost power converter. Wind power is supplied through an AC-DC converter and then a DC–DC boost converter, while the batteries are charged via a charge controller. As the research mainly focuses on the effect of CPL in the DC microgrid, the load is considered a CPL, as shown in the figure. The control algorithm is executed using the WAVECT controller, a real-time control prototyping system. The control signal from the WAVECT controller is provided to the DC–DC converters, which are used to connect the different sources to the DC bus, as shown in Fig. 24. Through this analysis, the effectiveness of the controller for the hybrid system can be easily verified during the presence of a constant power load, as the objective of this research is to develop a robust controller for voltage regulation of the hybrid DC microgrid with CPL. The effectiveness of the proposed controller can be tested by varying the load in the CPL. A step change in load power is applied as shown in Fig. 25. A reduction in the CPL value from 2.1 to 1.3 KW has been applied to the system. Figures 26, 27, 28 and 29 illustrate the performance of the system during this variation in the load. Dynamic changes in the load current are shown in Fig. 26, where the change in load current from 3.4A to 2A is depicted. As we have mainly two supplies functioning in this setup, such as the PV solar panel and the battery, the input power from the battery will also change according to the dynamics in load. As a result, the battery current changes from 1.3A to 0.1A, as shown in Fig. 27. However, at that instance, since the supply from the PV solar panel remains constant, it will provide input to the DC bus depending on the climate of that season (here almost 1.3 KW). The voltage supplied by the solar panel is 220V, and the current value is 6A, as mentioned in Fig. 29 . From the dynamic waveform of the DC bus voltage, the stability of the system can be analyzed during uncertainty. Figure 28 illustrates the voltage across the DC bus during these load power variations. The DC bus voltage remains at 600V throughout the load changes. From this analysis, the robustness of the controller can be verified during load variation. However, as future work, the performance of the proposed controller during dynamic changes in supply can also be verified.

An experimental DC microgrid setup is used to evaluate the suggested control scheme, as demonstrated in Fig. 30. The main components of this setup include a solar PV panel and battery as sources of supply; a WAVECT controller and its console; and a PCC. The PCC represents the constant power load, which is the primary focus of the setup. This constant power load is represented through the PCC, which is the point where the load interacts with the system. Constant power loads mainly considered in this setup are computers, laptops, mobile chargers, and so on. When different loads are disconnected in this setup, uncertainty is created, such as a load variation scenario. Through this load variation, the effectiveness of the proposed controller can be analyzed, particularly in terms of its ability to handle fluctuations and maintain system stability under dynamic conditions.

Conclusion

This paper has described the DC-to-DC boost power converter instability issue that the CPL is causing in the DC microgrid. To address this issue, both linear and nonlinear controllers can be used. A linear controller cannot ensure that the intended equilibrium point will remain stable globally, while a conventional nonlinear controller is difficult to build and changes depending on the factors of the system. A nonlinear controller, such as the passivity-based controller (PBC), has been developed to enhance the system’s control resilience against fluctuations in supply and demand conditions. For the hybrid DC microgrid, DC bus voltage regulation in conjunction with the EL-theory-based passivity-based control technique was recommended in relation to the system passivity property. By regulating the dissipated energy in the system, the oscillatory behavior brought on by the CPL can be addressed by using the PBC. The use of a virtual damping matrix will render the closed-loop control system completely passive, or stable. Consequently, the PBC method offers an equilibrium point that is globally asymptotically stable. Control robustness against uncertainty is provided by the suggested controller based on experimental results and MATLAB simulation results. The proposed control system gives improved anti-disturbance rejection compared to other nonlinear controllers. It can recover from disturbances faster than alternative nonlinear controllers. Larger signal stability can be achieved with the proposed controller compared to a conventional linear controller. However, future studies could focus on extending the experimental setup to incorporate additional challenging conditions, such as higher load variations, renewable source outages, or fault scenarios. These considerations would further validate the robustness and scalability of the proposed control strategy in real-world applications. And future iterations of the research will examine other converter topologies and loads, including constant voltage loads (CVLs) and CPLs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Nithara, P. V. Comparative analysis of different control strategies in microgrid. Int. J. Green Energy 18, 1249–1262 (2021).

Hossain, E., Perez, R., Nasiri, A. & Padmanaban, S. A comprehensive review on constant power loads compensation techniques. IEEE Access 6, 33285–33305 (2018).

Rai, I. & Anand, R. Design of suboptimal controller for improved dynamic response in dc microgrid linked to multiple constant power loads. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing and Electrical Circuits and Electronics (ICDCECE), 1–5 (IEEE, 2022).

Nithara, P. et al. Brayton-Moser passivity based controller for constant power load with interleaved boost converter. Sci. Rep. 14, 28325 (2024).

Gaonkar, V., Ramprabhakar, J. & Anand, R. Coordination control for battery augmented roof top wind-solar integrated system. In 2023 First International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics and Computational Intelligence (ICAEECI), 1–9 (IEEE, 2023).

Nithara, P. et al. Nonlinear disturbance observer-based passivity controller for an interleaved boost converter feeding a constant power load. In 2025 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Technologies in Computing, Electrical and Electronics (IITCEE), 1–6 (IEEE, 2025).

Rai, I., Rajendran, A., Lashab, A. & Guerrero, J. M. Nonlinear adaptive controller design to stabilize constant power loads connected-dc microgrid using disturbance accommodation technique. Electr. Eng. 2023, 1–16 (2023).

Srinivasan, M. & Kwasinski, A. Control analysis of parallel dc-dc converters in a dc microgrid with constant power loads. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 122, 106207 (2020).

Baskaran, J. et al. Cost-effective high-gain dc-dc converter for elevator drives using photovoltaic power and switched reluctance motors. Front. Energy Res. 12, 1400651 (2024).

Rai, I., Ravishankar, S. & Anand, R. Review of dc microgrid system with various power quality issues in “real time operation of dc microgrid connected system. Majlesi J. Mechatron. Syst. 8, 35–44 (2020).

Arora, S., Balsara, P. & Bhatia, D. Input-output linearization of a boost converter with mixed load (constant voltage load and constant power load). IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 34, 815–825 (2018).

Duddeti, B. B., Naskar, A. K., Meena, V., Bahadur, J. & Hameed, I. A. Constrained search space selection based optimization approach for enhanced reduced order approximation of interconnected power system models. Sci. Rep. 15, 7999 (2025).

Guan, Y., Xie, Y., Wang, Y., Liang, Y. & Wang, X. An active damping strategy for input impedance of bidirectional dual active bridge dc-dc converter: Modeling, shaping, design, and experiment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 68, 1263–1274 (2020).

Qu, Z., Ebrahimi, S., Amiri, N., Jatskevich, J. & Pizniur, A. Adaptive control method for stabilizing dc distribution systems with constant-power loads based on tunable active damping. In 2018 IEEE 19th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Wu, J. & Lu, Y. Adaptive backstepping sliding mode control for boost converter with constant power load. IEEE Access 7, 50797–50807 (2019).

Singh, S., Fulwani, D. & Kumar, V. Robust sliding-mode control of dc/dc boost converter feeding a constant power load. IET Power Electron. 8, 1230–1237 (2015).

Singh, S., Fulwani, D. & Kumar, V. Emulating dc constant power load: A robust sliding mode control approach. Int. J. Electron. 104, 1447–1464 (2017).

Karami, Z. et al. Hybrid model predictive control of dc-dc boost converters with constant power load. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 36, 1347–1356 (2020).

Andrés-Martínez, O., Flores-Tlacuahuac, A., Ruiz-Martinez, O. F. & Mayo-Maldonado, J. C. Nonlinear model predictive stabilization of dc-dc boost converters with constant power loads. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9, 822–830 (2020).

Al-Nussairi, M. K., Bayindir, R. & Hossain, E. Fuzzy logic controller for dc-dc buck converter with constant power load. In 2017 IEEE 6th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), 1175–1179 (IEEE, 2017).

Wu, J. & Lu, Y. Feedback linearization adaptive control for a buck converter with constant power loads. In 2018 IEEE International Power Electronics and Application Conference and Exposition (PEAC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Sulligoi, G. et al. Multiconverter medium voltage dc power systems on ships: Constant-power loads instability solution using linearization via state feedback control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 5, 2543–2552 (2014).

Meena, G. et al. Optimizing power flow and stability in hybrid ac/dc microgrids: Ac, dc, and combined analysis. Math. Comput. Appl. 29, 108 (2024).

Meena, V., Singh, V. P., Padmanaban, S. & Benedetto, F. Rank exponent-based reduction of higher order electric vehicle systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 73, 12438–12447. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2024.3387975 (2024).

Rahimi, A. M., Williamson, G. A. & Emadi, A. Loop-cancellation technique: A novel nonlinear feedback to overcome the destabilizing effect of constant-power loads. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 59, 650–661 (2009).

Hassan, M. A. & He, Y. Constant power load stabilization in dc microgrid systems using passivity-based control with nonlinear disturbance observer. IEEE Access 8, 92393–92406 (2020).

Hassan, M. A., Su, C.-L., Chen, F.-Z. & Lo, K.-Y. Adaptive passivity-based control of a dc-dc boost power converter supplying constant power and constant voltage loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69, 6204–6214 (2021).

Xu, Q., Zhang, C., Wen, C. & Wang, P. A novel composite nonlinear controller for stabilization of constant power load in dc microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 10, 752–761 (2017).

Sarrafan, N. et al. A novel fast fixed-time backstepping control of dc microgrids feeding constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 70, 5917–5926 (2022).

Alipour, M. et al. Observer-based backstepping sliding mode control design for microgrids feeding a constant power load. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 70, 465–473 (2022).

Ahmadi, F., Batmani, Y., Bevrani, H., Yang, T. & Cui, C. Finite-time synergetic controller design for dc microgrids with constant power loads. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid (2023).

Kondratiev, I., Santi, E., Dougal, R. & Veselov, G. Synergetic control for dc-dc buck converters with constant power load. In 2004 IEEE 35th Annual Power Electronics Specialists Conference (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37551), vol. 5, 3758–3764 (IEEE, 2004).

Cupelli, M., Monti, A., De Din, E. & Sulligoi, G. Case study of voltage control for mvdc microgrids with constant power loads-comparison between centralized and decentralized control strategies. In 2016 18th Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference (MELECON), 1–6 (IEEE, 2016).

Yousefizadeh, S. et al. Tracking control for a dc microgrid feeding uncertain loads in more electric aircraft: Adaptive backstepping approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 66, 5644–5652 (2018).

Meena, V., Agrawal, R., Gumber, R., Tipare, A. R. & Singh, V. Order reduction of continuous interval zeta converter model using direct truncation method. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP), 1–6 (IEEE, 2022).

Shao, X., Hu, J. & Zhao, Z. Stabilisation strategy based on feedback linearisation for dc microgrid with multi-converter. J. Eng. 2019, 1802–1806 (2019).

Asmy, N. A., Ramprabhakar, J., Anand, R., Meena, V. & Jadoun, V. K. A relative analysis to cascaded fractional-order controllers in microgrid non-minimum phase converters using eho. Sci. Rep. 15, 10333 (2025).

Varshney, T. et al. Fopdt model and chr method based control of flywheel energy storage integrated microgrid. Sci. Rep. 14, 21550 (2024).

Patil, N. et al. Energy trading interface for grid-tied wind-solar power generation system. In 2024 Control Instrumentation System Conference (CISCON), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Chaitanya, I. S. et al. Performance evaluation of eho and gwo optimization techniques for pi controller tuning of boost converter in photovoltaic based microgrid. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), 1529–1534 (IEEE, 2024).

DebBarman, S., Namrata, K., Kumar, N. & Meena, V. Optimising power distribution systems: Solar-powered capacitors and cost reduction through meta-heuristic methods. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Inform. 12, 188–212 (2024).

Abadi, S. A. G. K., Habibi, S. I., Khalili, T. & Bidram, A. A model predictive control strategy for performance improvement of hybrid energy storage systems in dc microgrids. IEEE Access 10, 25400–25421 (2022).

Ul Islam Khan, M. et al. Securing electric vehicle performance: Machine learning-driven fault detection and classification. IEEE Access 12, 71566–71584 (2024).

Mathur, A. et al. Data-driven optimization for microgrid control under distributed energy resource variability. Sci. Rep. 14, 10806 (2024).

Asmy, N. A. et al. The efficiency duel-pi vs. fopi control: The next frontier in solar pv boost converter system optimisation. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Self Sustainable Artificial Intelligence Systems (ICSSAS), 1535–1540 (IEEE, 2024).

Yadav, U. K., Meena, V., Sahu, U. K. & Singh, V. Approximation of stand-alone boost converter enabled hybrid solar-photovoltaic controller system. In International Conference on Robotics, Control, Automation and Artificial Intelligence, 235–248 (Springer, 2022).

Deepika, D. et al. Order reduction of autonomous microgrids using pade and routh approximation. In 2024 4th International Conference on Sustainable Expert Systems (ICSES), 171–176 (IEEE, 2024).

Ortega, R. et al. Euler–Lagrange Systems (Springer, 1998).

Chaudhary, R., Singh, V., Mathur, A., Meena, V. & Murari, K. Truncation-based approximation of autonomous microgrid. In 2024 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Meena, V., Singh, V. & Guerrero, J. M. Investigation of reciprocal rank method for automatic generation control in two-area interconnected power system. Math. Comput. Simul. 225, 760–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matcom.2024.06.007 (2024).

Van der Schaft, A. L2-Gain and Passivity Techniques in Nonlinear Control (Springer, 2000).

Namazi, M. M., Koofigar, H. R. & Ahn, J.-W. Active stabilization of self-excited switched reluctance generator supplying constant power load in dc microgrids. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9, 2735–2744 (2020).

Tofighi, A. & Kalantar, M. Interconnection and damping assignment and Euler–Lagrange passivity-based control of photovoltaic/battery hybrid power source for stand-alone applications. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. C 12, 774–786 (2011).

Gil-Gonzalez, W., Montoya, O., Herrera-Orozco, A. & Serra, F. Adaptive ida-pbc applied to on-board boost converter supplying a constant power load. In 2020 IEEE ANDESCON, 1–5 (IEEE, 2020).

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study, conception, and design. All authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This paper does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Authors transfer to Springer the publication rights and warrant that our contribution is original.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nithara, P.V., Anand, R., Ramprabhakar, J. et al. A passivity based nonlinear controller for hybrid DC microgrid with constant power loads. Sci Rep 15, 16904 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01390-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01390-8