Abstract

The expression of ubiquitin-like molecule interferon-stimulated gene 15 kDa (ISG15) and its post-translational modification (ISGylation) are significantly activated by interferons or pathogen infections, highlighting their roles in innate immune responses. Over 1100 proteins have been identified as ISGylated. ISG15 is removed from substrates by interferon-induced ubiquitin-specific peptidase 18 (USP18) or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-derived papain-like protease. High ISGylation levels may help prevent the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Polyamines (spermidine and spermine) exhibit anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and mitochondrial functions. However, the relationship between nutrients and ISGylation remains unclear. This study assessed the effects of spermine and spermidine on ISGylation. MCF10A and A549 cells were treated with interferon-alpha, spermine, or spermidine, and the expression levels of various proteins and ISGylation were measured. Spermine and spermidine dose-dependently reduced ISGylation. Additionally, spermidine directly interacted with ISG15 and USP18, enhancing their interaction and potentially reducing ISGylation. Therefore, spermidine may prevent ISGylation-related immune responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines that are crucial for defending against bacterial and viral infections1,2,3. IFN-stimulated gene 15 kDa (ISG15) is the first reported ubiquitin-like molecule induced by IFNs4,5,6,7. It forms covalent conjugates with over 1100 proteins8,9, resembling protein ubiquitination10. ISG15 is activated by the E1 enzyme, ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like protein (UBE1L), in an ATP-dependent manner11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Following activation, ISG15 is transferred to the E2 enzyme, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 L6 (UBE2L6), followed by substrate modification through ISGylation, which is recognized by ISG15 ligases11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Viral proteins are primarily translated into infected cells, and newly synthesized proteins can be modified by ISG1518. ISGylation may interfere with pathogen protein function. For example, ISGylation of the human papillomavirus (HPV) L1 capsid protein inhibits the infectivity of HPV16 pseudoviruses4,18. Additionally, cellular proteins involved in antiviral defense or export of viral particles can be ISGylated5. Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 18 (USP18) is an IFN-induced protein that acts as an ISG15 isopeptidase to remove ISG15 from its substrates (deISGylation)19,20,21,22. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel human beta-coronavirus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)23. Similar to the function of USP18, the SARS-CoV-2-derived papain-like protease (PLpro) can remove ISG15 from substrates24,25,26,27,28. Therefore, we hypothesized that ISGylation may delay SARS-CoV-2 propagation. However, the primary substrate protein that prevents SARS-CoV-2 propagation has not been identified. In summary, ISGylation modulates immune responses during infection and under various stressful conditions.

Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine [SPD], and spermine [SPM]) are small aliphatic bioactive polycations essential for various cellular functions, including autophagy, immune response, transcription, translation, cell cycle, and stress responses. Additionally, they are associated with cancer, aging, and neurodegenerative diseases29,30,31,32,33. Polyamines are strongly implicated in cancer, and reducing their levels may limit tumorigenesis, though attempts to develop drugs reducing polyamine levels have been unsuccessful29,32. SPD enhances mitochondrial function and activates CD8+ T cells, contributing to the programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) blockade immunotherapy34. In contrast, ISG15 destabilizes PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and aids cancer immunotherapy; however, the role of PD-L1 ISGylation remains unclear35. Free intracellular and extracellular ISG15 and ISGylation are involved in antitumor or protumor activity36,37. Polyamine levels are regulated through oral uptake (dietary polyamines), cellular metabolism (biosynthesis and catabolism), and microbiota-derived intestinal production33. Foods such as natto (a fermented soybean-based Japanese dish) and mature cheese are rich in polyamines38,39. Since polyamine catabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS)40, maintaining appropriate intracellular polyamine catabolism is crucial for oxidative homeostasis. RNA viruses, such as Chikungunya, Zika, Rift Valley fever, and La Crosse viruses, require polyamines for transcription, translation, and replication41,42, facilitating viral infections by enhancing viral component synthesis41,42,43,44. Type I IFN induces spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SAT1), which acetylates (inactivates) SPD and SPM, limiting viral replication41.

SPD inhibits inflammatory M1 macrophages and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine45, whereas upregulating anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, crucial for macrophage immunomodulation45,46. SPD also activates indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1)-dependent immunosuppressive effects in dendritic cells (DCs)47. Moreover, SPM and SPD may convert immunogenic DCs into tolerant DCs, inducing anergic cytotoxic CD8+ T cells48,49. Polyamines reduce natural killer (NK) cell cytolytic activity, protecting tumors from the immune response50, whereas polyamines deprivation enhances NK cell activity51. SPD post-translationally modifies (hypusinates) the translation factor EIF5A, inducing autophagy and improving aged B cell function52.

ISGylation is a well-known protein modification that is induced by IFNs. However, the chemicals or nutrients facilitating ISGylation remain unclear, except for nitric monoxide53 and curcumin54. Nitrosylation of ISG15 prevents ISG15 homodimerization, which increases the number of ISG15 monomers participating in ISGylation53. Curcumin prevents ISG15 activation by UBE1L, thereby reducing ISGylation. We assessed the effect of several food-derived chemicals on ISGylation, as they may regulate ISGylation similarly to curcumin. In this study, we report that SPD downregulates ISGylation by directly interacting with ISG15 and USP18. SPD enhanced ISG15–USP18 interaction, contributing to the reduction of ISGylation in its presence. SARS-CoV-2 PLpro is an enzyme that removes ISG15, reducing ISGylation. The daily intake of high amounts of SPD may enhance SARS-CoV-2 propagation if ISGylation plays a role in preventing viral replication, and it may also potentially prevent ISGylation-related immune responses.

Results

SPD downregulates ISGylation

IFNs induce ISGylation8,9 and activation of SAT1 that acetylates SPD and SPM, thereby restricting replication of Chikungunya, Zika, Rift Valley fever, and La Crosse viruses41. This indicated a potential relationship between ISGylation, SPD, and SPM. To explore this, the MCF10A human mammary gland epithelial cell line was used because it exhibits relatively stronger ISGylation in response to human IFN-α than that of other cell lines. MCF10A cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IFN-α, SPD, or SPM for 2 days. Because fetal bovine serum (FBS) in the culture medium may contain SPD and SPM, MCF10A cells were also subjected to stimulation by IFN-α in the absence of FBS. Subsequently, cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-ISG15, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (HECT domain and RCC1-like domain-containing protein 5, Herc5), and anti-USP18 antibodies (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). Because ISG15 is a ubiquitin-like protein and its modification system is similar to the ubiquitination system4,5,6,7,55, ubiquitination was also examined using an anti-ubiquitin antibody (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). IFN-α induces ISG15 expression, a protein with a molecular weight of approximately 15 kDa and ISGylation at 40–200 kDa and UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18, as reported previously (Figs. 1A, B, and Supplementary Fig. 1)12,13,14,53,54,56,57,58. ISGylation was downregulated in the presence of 400 µM SPM or SPD. Since SPD more strongly downregulated ISGylation than SPM, we examined higher SPM concentrations (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Up to 1.2 mM SPM downregulated ISGylation in a dose-dependent manner. The expression of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18 was unaffected by SPD or SPM and did not correlate with ISGylation downregulation. Ubiquitination was unaffected, indicating a selective effect of SPM and SPD on ISGylation. Large errors may result from dynamic induction of proteins by IFN-α and variations in the stability of ubiquitinated proteins. We then examined cell growth and death under FBS-free conditions, which typically support growth and prevent death. MCF10A cells (3 × 105) were plated in a 6 cm dish, with or without FBS, and cell numbers were counted daily (Fig. 1C). Cells grew slower and had lower viability without FBS, though most remained viable. These data indicate that SPM and SPD downregulate ISGylation in the absence of FBS, with slower cell proliferation and slightly reduced viability compared to serum-containing conditions. We also used RAW264.7 macrophage cells as immune-related cells. RAW264.7 cells were cultured with or without lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which induces ISGylation59, and treated with SPD or SPM for 2 days without FBS. Subsequently, cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and IB with anti-mouse ISG15 antibody (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1). ISGylation was downregulated by 800 µM SPM and 200–800 µM SPD, highlighting their role in immune-related cells (Figs. 1D, E, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Downregulation of ISGylation and UBE2L6, but not of UBE1L, Herc5, and USP18 through SPD treatment. (A) SPM and SPD partially prevent ISGylation and UBE2L6 expression in MCF10A cells. MCF10A cells are stimulated with hIFN-α with or without SPM or SPD (100, 200, or 400 µM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting with anti-hISG15, anti-ubiquitin, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, or anti-USP18 antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18 expression levels, and that of ISGylation and ubiquitination from (A). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells stimulated by human IFN-α is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as not significant (N.S.), whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (C) Serum deprivation slows down MCF10A cell growth. MCF10A cells (3 × 105) are cultured with or without serum in a 6 cm dish, and cell numbers are counted daily. Cell viability is analyzed by trypan blue staining, with stained cells considered dead. (D) SPM and SPD partially prevent ISGylation in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells are stimulated by LPS with or without SPM or SPD (200, 400, or 800 µM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting with an anti-mouse ISG15 antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from five independent experiments. (E) Quantification of ISGylation in (D). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells stimulated by LPS is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

Downregulation of polyamine biosynthesis enhances ISGylation

Subsequently, we assessed the effects of a polyamine biosynthesis inhibitor on ISGylation. Ornithine decarboxylase 1 (ODC1) is a rate-limiting enzyme involved in polyamine biosynthesis32. Difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) is an irreversible inhibitor of ODC1. MCF10A cells were cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of IFN−α and/or DFMO for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by IB with anti-ISG15, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, anti-USP18, and anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 4). ISGylation and the expression of ISGylation-related enzymes, including ISG15-removing USP18, were enhanced when cultured with 0.5 or 1.0 mM DFMO (Figs. 2A, B, and Supplementary Fig. 4). Free ISG15 tended to increase with DFMO treatment, though this was not significant. In contrast, ubiquitination tended to decrease with DFMO treatment, suggesting a relationship between higher ISGylation and lower ubiquitination. Ubiquitin and ISG15 target the lysine residue of substrate proteins, and ISG15 has the potential to compete with ubiquitination37, thereby indirectly regulating protein degradation37. If DFMO upregulates ISGylation by downregulating ubiquitination, DFMO should strongly increase ISGylation when UBA1, required for ubiquitination, is knocked down. To examine this, we knocked down UBA1 in MCF10A cells using two different siRNAs, and cells were cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of IFN−α and/or DFMO for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with anti-UBA1, anti-ISG15, and anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Fig. 4). UBA1 knockdown did not significantly reduce ubiquitinated proteins60, likely because these ubiquitin modifications contribute to signal transduction rather than proteasomal degradation. DFMO treatment increased ISGylation in UBA1-knockdown cells (#1 and #2), similar to control-knockdown cells (Fig. 2D), indicating that DFMO-dependent ISGylation upregulation is independent of ubiquitination. Notably, ISGylation upregulation was less than in cells without siRNA transfection (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting direct or indirect effects of the reagents. UBA1 knockdown tended to enhance ISGylation, but this was not significant.

Upregulation of ISGylation and the expression of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18 through difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) treatment in MCF10A cells. (A) DFMO upregulates ISGylation and the expression of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18. MCF10A cells are stimulated by hIFN-α with or without DFMO (0.5 or 1.0 mM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting with anti-ISG15, anti-ubiquitin, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, or anti-USP18 antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from five independent experiments. (B) Quantification of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, USP18, and free ISG15 expression levels, as well as ISGylation and ubiquitination from (A). Each signal is normalized to Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells stimulated by human IFN-α is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (C) Upregulation of ISGylation by DFMO in the absence of UBA1. UBA1-knockdown or control MCF10A cells are stimulated with hIFN-α with or without DFMO (0.5 mM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting using anti-UBA1, anti-ISG15, and anti-ubiquitin antibodies. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from three independent experiments. (D) Quantification of UBA1 expression levels, ISGylation, and ubiquitination from (C). Each signal is normalized to Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of UBA1 and ubiquitination in control knockdown cells stimulated by hIFN-α is set to 1. In contrast, the signal intensity of ISGylation in control and UBA1-knockdown cells stimulated by hIFN-α is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

These data indicate that preventing polyamine biosynthesis enhances ISGylation. To examine its broader relevance, A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells, which exhibit relatively strong ISGylation similar to MCF10A and RAW264.7 cells, were used. Cell growth and death were examined with or without FBS. A549 cells (2 × 105) were plated in a 6 cm dish with or without FBS, and cell numbers were counted daily (Fig. 3A). Cells grew slower without FBS, and cell viability was lower than in the FBS condition, although most cells remained viable. The cells were cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of IFN−α and/or DFMO for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by IB with anti-ISG15, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, anti-USP18, and anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 5). As anticipated, ISGylation was slightly enhanced when cultured with 0.5 or 1.0 mM DFMO. However, the upregulation was less than that observed in MCF10A cells, suggesting that the DFMO effect is cell-type-dependent. The expression of UBE1L, UBE2L6, and USP18 was enhanced when cultured with DFMO (Figs. 3B, C, and Supplementary Fig. 5). In contrast, Herc5 expression remained unaffected under these conditions. Ubiquitination tended to be downregulated. These results indicate that DFMO-induced ISGylation is not cell-type-specific, although the effect varies by cell type.

Upregulation of ISGylation through DFMO treatment and downregulation of ISGylation through SPD treatment in the presence of DFMO in A549 cells. (A) Serum deprivation slows down A549 cell growth. A549 cells (2 × 105) are cultured with or without serum in a 6 cm dish, and cell numbers are counted daily. Cell viability is analyzed by trypan blue staining, with stained cells considered dead. (B) DFMO slightly upregulates ISGylation but not ubiquitination. A549 cells are stimulated by hIFN-α with or without DFMO (0.5 or 1.0 mM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting using an anti-ISG15, anti-ubiquitin, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, or anti-USP18 antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from five independent experiments. (C) Quantification of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18 expression levels, as well as that of ISGylation and ubiquitination in (B). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells stimulated by human IFN-α is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (D) SPD partially prevents ISGylation, ubiquitination, UBE1L, UBE2L6, and USP18 expression in the A549 cells. A549 cells are stimulated by hIFN-α with or without SPD (0.5 or 1.0 mM) in the presence of DFMO (1.0 mM) for 2 days. The cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting with anti-ISG15, anti-ubiquitin, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, or anti-USP18 antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data of three independent experiments. (E) Quantification of UBE1L, UBE2L6, Herc5, and USP18 expression levels, and that of ISGylation and ubiquitination in (D). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells stimulated by human IFN-α is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

We further assessed the effect of SPD on ISGylation in DFMO-treated A549 cells. The cells were cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of IFN-α with or without SPD and DFMO for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by IB with anti-ISG15, anti-UBE1L, anti-UBE2L6, anti-Herc5, anti-USP18, and anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Fig. 3D and Supplementary Fig. 5). ISGylation and USP18 expression were reduced when cultured with 0.5 or 1.0 mM SPD in the presence of DFMO (Figs. 3D, E, and Supplementary Fig. 5). The expression of UBE1L and ubiquitination were downregulated when cultured with 1.0 mM SPD. UBE2L6 and USP18 expression were reduced when cultured with SPD. The expression of Herc5 was unaffected by SPD. In summary, SPD downregulated ISGylation in DFMO-treated A549 cells. However, it remains unclear whether the downregulation of ISGylation is dependent on the reduced expression of ISGylation enzymes.

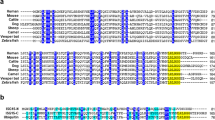

ISG15 directly binds to SPD and SPM

Given that SPD selectively binds to specific proteins, such as hydroxyl coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenase subunits α and β34, we speculated that ISG15 binds to SPD and SPM. To assess this possibility, recombinant human ISG15 (hISG15) and mouse ISG15 (mISG15) were purified from E. coli (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 6). Each recombinant ISG15 was incubated with SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose and control sepharose. Subsequently, each sepharose was washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by IB with anti-mISG15 or anti-hISG15 antibody (Figs. 4B, C, and Supplementary Fig. 6). mISG15 was pulled down by SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose in the presence of 1% Triton X-100, indicating its direct interaction with SPD and SPM (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 6). However, we did not detect any interactions between hISG15 and SPD or SPM under similar conditions (data not shown), indicating a weaker interaction than that with mISG15. Therefore, the detergent was changed to 0.25% CHAPS, and a direct interaction between hISG15 and SPD or SPM was observed (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. 6). These data indicate that mISG15 and hISG15 directly interact with SPD or SPM. The amino acids of mISG15, which are crucial for this interaction, may be mutated to different amino acids in hISG15. Because SPD and SPM are positively charged in the cell29,30,31,32,33, we assumed that the negatively charged amino acids (glutamic and aspartic acids) of mISG15 may be crucial for the interaction between SPD and SPM, and a few of these may be mutated in hISG15. The amino acid sequence alignment of mISG15 and hISG15 highlighted several non-conserved glutamic and aspartic acids. Of these, asparagine at position 87, alanine at position 105, and leucine at position 135 in hISG15 were mutated (Fig. 4D). We hypothesized that if these amino acids are associated with the interaction between SPD and SPM, mutating the corresponding amino acids in mISG15 to those found in hISG15 may reduce the interaction of mISG15 with SPD or SPM. Therefore, recombinant mISG15 mutants (E87N, D103A, or E133L) were purified from E. coli (Fig. 4E). Each recombinant mISG15 (wild type [WT] or mutant) was incubated with SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose and control sepharose. mISG15(E87N) was pulled down by SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose in the presence of 1% Triton X-100, but this result was not consistent, leading to large error bars (Figs. 4F, G, and Supplementary Fig. 6). The interaction between mISG15(E87N) and SPD or SPM may be highly sensitive to pull-down conditions. In contrast, the interaction of mISG15 mutant (D103A, E133L) with SPD or SPM was downregulated compared to WT mISG15, indicating that aspartic acid at position 103 and glutamic acid at position 133 are crucial for binding to SPD or SPM. Next, we examined the acidic amino acids in hISG15 and their role in interaction with SPD and SPM. Sequence alignment of mISG15 and hISG15 highlighted several conserved acidic amino acids (Fig. 4D). D119/D120 of hISG15 correspond to E117/D118 of mISG15, and E132/D133 of hISG15 align with E130/D131 of mISG15. These amino acids may be critical for polyamine binding, and mutations could affect the interaction. Recombinant hISG15 mutants (D119/120A, E132A/D133A) were purified from E. coli (Fig. 4H and Supplementary Fig. 6). Each recombinant hISG15 (WT or mutant) was incubated with SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose and control sepharose in 0.25% CHAPS (Fig. 4I and Supplementary Fig. 6). The interaction of hISG15(D119/120A) with SPD was reduced compared to WT ISG15, whereas hISG15(E132A/D133A) showed no change in SPD interaction (Figs. 4I and J). In contrast, hISG15(E132A/D133A) interacted more strongly with SPM than WT ISG15, whereas hISG15(D119/120A) showed no change. These results suggest that E132/D133 of hISG15 weaken the interaction with SPM. Overall, these data indicate that several acidic amino acids are involved in the interaction with SPD and SPM.

ISG15 directly binds to SPD and SPM. (A) Purification of mouse ISG15 (mISG15) and human ISG15 (hISG15). GST-tagged mISG15 and hISG15 are expressed in Escherichia coli and purified using Glutathione sepharose 4B beads. GST tag is removed by PreScission Protease, and purity is confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining. (B) mISG15 directly binds to SPD and SPM. Recombinant mISG15 is pulled down using SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-mISG15 antibody. Representative data from five independent experiments. (C) hISG15 directly binds to SPD and SPM. Recombinant hISG15 is pulled down using SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose, followed by immunoblotting using an anti-hISG15 antibody. Representative data of three independent experiments. (D) Amino acid sequence alignment of hISG15 and mISG15. The numbers indicate amino acid positions in each protein. Acidic amino acids are represented in bold font. Loss of acidic amino acids in hISG15 is boxed, and conserved acidic amino acid sequences are underlined in red. Amino acids that are removed when both ISG15 proteins mature are underlined in black. Both ISG15 ends terminate with -LRLRGG. (E) Purification of wild-type(WT) and mutant mISG15. GST-tagged mISG15 are expressed in E. coli and purified using Glutathione sepharose 4B beads. GST tag is removed by PreScission Protease, and purity is confirmed by SDS-PAGE and CBB staining. (F) D103A or E133L mutation of mISG15 reduced interaction with SPD and SPM. Recombinant mISG15(WT or mutant) is pulled down using SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose, followed by immunoblotting using anti-mISG15 antibody. Representative data from five independent experiments. (G) Quantification of SPD- or SPM-bound mISG15 in (F). The signal intensity of SPD- or SPM-bound mISG15(WT) is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (H) Purification of mutant hISG15. GST-tagged hISG15 are expressed in E. coli and purified using Glutathione sepharose 4B beads. The GST tag is removed by PreScission Protease, and purity is confirmed by SDS-PAGE and CBB staining. (I) D119/120A mutation of hISG15 reduces interaction with SPD, and E132A/D133A mutation increases interaction with SPM. Recombinant hISG15 (WT or mutant) is pulled down using SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-hISG15 antibody. Representative data from five independent experiments. (J) Quantification of SPD- or SPM-bound hISG15 from (I). The signal intensity of control pulldown is subtracted from that of SPD- or SPM-bound hISG15. The signal intensity of SPD- or SPM-bound hISG15(WT) is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of five independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

D103A or E133L mutation in mISG15 upregulates ISGylation

Given that the D103A or E133L mutations in mISG15 reduced the interaction with SPD or SPM more than that in WT mISG15, these mutations may affect the ISG15 structure. If the ISG15 structure is altered by a mutation, it may result in the downregulation of ISGylation due to the inability of UBE1L to recognize the altered structure. However, if SPD reduced ISGylation by binding to ISG15, then the mISG15 (D103A or E133L) mutant, which has lost the SPD-binding ability, should exhibit enhanced ISGylation, provided that the mutation did not affect the overall ISG15 structure. To assess the effect of the D103A or E133L mutation on ISG15 structure and ISGylation, the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T was used owing to its high transfection efficiency. WT or mutant FLAG-tagged mISG15 (FLAG-mISG15), Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells, with or without UBE1L, in the presence of 1 mM SPD and FBS. 2 days after transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by IB with anti-FLAG, anti-UBE1L, anti-Ube2l6, and anti-HA antibodies (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. 7). ISGylation of FLAG-mISG15 (E87N) was similar to that of the WT (Figs. 5A, B, and Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, the ISGylation of FLAG-mISG15 (D103A) and FLAG-mISG15 (E133L) was upregulated compared to that of the WT, although the expression of UBE1L, Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 was unaffected by mutant ISG15 expression. These data indicate that the D103A or E133L mutations may not affect ISG15 structure because they are recognized by ISGylation enzymes. Additionally, the upregulation of ISGylation by the D103A or E133L mutation (Figs. 5A, B, and Supplementary Fig. 7) and reduced binding of those mutants to SPD (Figs. 4F, G, and Supplementary Fig. 6) indicate that SPD downregulates ISGylation by binding to ISG15.

D103A or E133L mutations in mISG15 enhanced ISGylation in the presence of SPD. (A) UBE1L, Ube2l6, HA-Herc5, and FLAG-mISG15 (wild type [WT] or mutant) are expressed in the HEK293T cells in the presence of SPD. 2 days after transfection, the cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting using anti-FLAG, anti-UBE1L, anti-Ube2l6, and anti-HA antibodies. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data of three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of FLAG-mISGylation, and UBE1L, Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 expression levels in (A). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells expressing FLAG-mISG15 (WT) and ISGylation system is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

SPD enhances ISGylation independently of ISG15 activation through UBE1L in HEK293T cell

To assess the effects of SPD on ISGylation, the ISGylation system was expressed in HEK293T cells, with or without SPD. FLAG-mISG15, Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells, with or without UBE1L, in the presence of FBS and varying concentrations of SPD (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Fig. 8). 2 days after transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with anti-FLAG, anti-UBE1L, anti-Ube2l6, and anti-HA antibodies. Ectopic ISGylation was upregulated in the presence of SPD; however, the expressions of UBE1L, Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 were unaffected (Figs. 6A, B, and Supplementary Fig. 8). ISGylation begins with ISG15 activation61. Briefly, a thiol-ester bond is formed between UBE1L and ISG15, which activates ISG1561. Curcumin, a bioactive compound present in turmeric62, downregulates ISGylation by preventing ISG15 activation by UBE1L54. Therefore, we speculated that SPD may enhance the activation of ISG15 by UBE1L under ectopic conditions. To assess this possibility, FLAG-mISG15 and UBE1L were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells in the absence of FBS with DFMO and varying SPD concentrations (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. 8). 2 days after transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with anti-FLAG and anti-UBE1L antibodies. UBE1L was detected at approximately 110 kDa, and additional major and minor UBE1L bands (approximately 140 kDa) were observed when FLAG-mISG15 was coexpressed (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. 8). The major UBE1L band was also detected using an anti-FLAG antibody, indicating that it was a UBE1L-ISG15 heterodimer covalently bound to a thioester. SPD treatment did not affect UBE1L-ISG15 formation, which indicates ISG15 activation, indicating that SPD is not involved in the activation of ISG15 by UBE1L (Figs. 6C, D, and Supplementary Fig. 8). In summary, SPD upregulated ectopically induced ISGylation, independently of ISGylation-related enzyme expression and ISG15 activation.

SPD enhances ISGylation independent of ISG15 activation by UBE1L in the HEK293T cell. (A) SPD enhances ectopically-induced ISGylation in the HEK293T cells. UBE1L, Ube2l6, HA-Herc5, and FLAG- mISG15 are expressed in the HEK293T cell with or without SPD (0.5 or 1.5 mM). 2 days after transfection, cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting with anti-FLAG, anti-UBE1L, anti-Ube2l6, and anti-HA antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data from four independent experiments. (B) Quantification of FLAG-mISGylation, and UBE1L, Ube2l6, and HA-Herc5 expression levels in (A). Each signal is normalized to that of Ponceau S staining. The signal intensity of cells expressing FLAG-mISG15 without SPD is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of four independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (C) SPD did not affect the activation of ISG15. UBE1L and FLAG-mISG15 are expressed in the HEK293T cells with or without SPD (0.5 or 1.5 mM) in the presence of DFMO (1 mM). 2 days after transfection, cell lysates are subjected to immunoblotting using an anti-FLAG or anti-UBE1L antibody. Ponceau S staining is used as a loading control. Representative data of four independent experiments. (D) Quantification of FLAG-mISG15-UBE1L in (C). The signal intensity of FLAG-mISG15-UBE1L without SPD is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of four independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively.

SPD directly binds to USP18 and enhances ISG15–USP18 interaction

SPD downregulated endogenous ISGylation (Figs. 1 and 3), and the SPD biosynthesis inhibitor, DFMO, upregulated ISGylation (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast, SPD upregulated the ectopically expressed ISGylation in the absence of USP18 (Fig. 6). These data indicated that USP18 may be involved in the downregulation of ISGylation by SPD under physiological conditions. Therefore, we assessed the interaction between USP18 and SPD. Recombinant human USP18 (hUSP18) was purified from E. coli (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Fig. 9). Two bands, approximately 35 and 65 kDa, were detected using the anti-USP18 antibody, with the 65 kDa band likely representing dimerized USP18, even under denaturing conditions. Recombinant USP18 was incubated with SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose and control sepharose. Subsequently, the washed sepharose was subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with an anti-USP18 antibody (Fig. 7B). hUSP18 was pulled down by SPD- or SPM-coated sepharose, indicating that hUSP18 directly interacts with SPD and SPM (Figs. 7B, C, and Supplementary Fig. 9). Because SPD interacts with ISG15 (Fig. 4) and USP18 (Figs. 7B, C, and Supplementary Fig. 7), it may facilitate the interaction between ISG15 and USP18. HA-hISG15 and hUSP18-V5 were transiently expressed in HEK293T cells with or without 0.5 mM SPD in the presence of FBS. 2 days after transfection, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-V5 antibody. The resulting immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with anti-HA and anti-V5 antibodies (Fig. 7D and Supplementary Fig. 9). SPD enhanced the interaction between ISG15 and USP18 (Figs. 7D, E, and Supplementary Fig. 9). Next, we examined SPD-dependent enhancement of the interaction between ISG15 and USP18 in A549 and MCF10A cells. A549 cells were cultured without FBS and stimulated with IFN-α in the presence of DFMO (0.5 mM) with or without SPD (0.5 mM) for 2 days. Cell lysates were subjected to IP using an anti-USP18 antibody. The resulting immunoprecipitates were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by IB with anti-ISG15 and anti-USP antibodies (Fig. 7F and Supplementary Fig. 9). SPD enhanced the interaction between endogenous ISG15 and USP18 (Figs. 7F, G, and Supplementary Fig. 9). This enhanced interaction between endogenous ISG15 and USP18 was also confirmed in MCF10A cells (Figs. 7H, I, and Supplementary Fig. 9). These data indicated that SPD directly interacts with USP18 and enhances its binding to ISG15.

SPD directly binds to hUSP18 and enhances ISG15–hUSP18 interaction. (A) Purification of hUSP18. GST-tagged hUSP18 is expressed in Escherichia coli and purified using Glutathione sepharose 4B beads. GST tag is removed by PreScission Protease, and purity is confirmed by SDS-PAGE, CBB staining, and immunoblotting with an anti-USP18 antibody. (B) hUSP18 directly binds to SPD and SPM. Recombinant hUSP18 is pulled down using SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose, followed by immunoblotting with an anti-USP18 antibody. Representative data of three independent experiments. (C) Quantification of SPD- or SPM-bound USP18 in (C). The signal intensity of SPD-bound hUSP18 is set as 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (D) SPD enhances hISG15–hUSP18 interaction. HA-hISG15 and hUSP18-V5 are expressed in the HEK293T cells with or without SPD (0.5 mM). 2 days after transfection, cell lysates are subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-V5 antibody and immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-V5 antibody. Representative data from four independent experiments. (E) Quantification of USP18-bound ISG15 in (D). HA signal is normalized by V5 signal after IP. The signal intensity of cells without SPD is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of four independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (F) SPD enhances endogenous hISG15–hUSP18 interaction. A549 cells are cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of hIFN-α, DFMO (0.5 mM), and SPD (0.5 mM) for 2 days. Cell lysates are subjected to IP using control (anti-FLAG antibody) or anti-USP18 antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-hISG15 and anti-USP18 antibody. Representative data from three independent experiments. (G) Quantification of USP18-bound ISG15 from (F). The signal intensity of each control IP is subtracted from that of USP18 IP. The ISG15 signal is normalized by the USP18 signal after IP. The signal intensity of cells without SPD is set to 1. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (H) SPD enhances endogenous hISG15–hUSP18 interaction in MCF10A cells. Cells are cultured without FBS in the presence or absence of hIFN-α and SPD (0.2 mM) for 2 days. Cell lysates are subjected to IP and immunoblotting as in (F). Representative data from three independent experiments. (I) Quantification of USP18-bound ISG15 from (H). USP18-bound ISG15 was calculated as in (G). Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. The means of different groups are compared using the Student’s t-test. p values greater than 0.05 are labeled as N.S., whereas p values less than 0.05 and 0.01 are labeled as * and **, respectively. (J) Crystal structure of the mISG15 and mUSP18 complex63. D103 and E133 of mISG15 are shown, with these amino acids binding to SPD and SPM. (K) Hypothetical model of the mechanism by which SPD downregulates ISGylation. SPD enhances ISG15–USP18 interaction, thereby increasing deISGylation. Additionally, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) papain-like protease (PLpro) has deISGylation activity. Maintaining higher ISGylation levels may enhance antiviral activity.

Study limitations

SPD and SPM have been demonstrated to interact directly with ISG15. However, it remains unclear whether SPD and SPM can also interact with ISG15 covalently bound to its substrate. The aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues in mISG15 at positions 103 and 133, respectively, are not believed to be masked by the substrate based on the ISG15 structure. Therefore, SPD and SPM should be able to interact with ISG15 on the substrate, but this was not examined. Additionally, we did not assess the concentrations of SPD and SPM in FBS, which could have influenced our results. The addition of SPD (e.g., 0.5 mM in Fig. 6A) to the culture medium caused certain differences, indicating that the SPD concentration in FBS should be lower than that used in the experiments.

Discussion

Based on the crystal structure of mouse USP18 (mUSP18) in complex with mISG15 (Fig. 7J)63, SPD and SPM may interact with D103 and E133 of mISG15, which are involved in binding SPD and SPM (Fig. 4). SPD and SPM likely stabilize the ISG15 structure and its binding to UPS18. Since USP18 is larger than ISG15 and may bind SPD and SPM at multiple sites, identifying specific binding sites is challenging. However, SPD or SPM may bridge and stabilize the ISG15-USP18 complex. The crystal structure of human USP18 with human ISG15 has not been solved but is predicted using AlphaFold64, suggesting similarity to the mUSP18-mISG15 complex. Mutant hISG15(D119/120A) interacted more weakly with SPD than WT (Figs. 4I and J). The corresponding E117/D118 of mISG15 form salt bonds with K107/H116, respectively63, but these residues are not conserved in hISG15, suggesting a different structure. If D119/D120 contribute to stability, D119/120A mutation may cause instability and weaker SPD binding. Additionally, D119/D120 may also be at the SPD-binding site, and their mutation weakens this interaction. In contrast, mutant hISG15(E132A/D133A) interacted more strongly with SPM than WT (Figs. 4I and J). If E132 and D133 are at the SPM-binding site and their negative charges hinder binding, E132A/D133A mutation improves binding by altering charge. The corresponding E130/D131 of mISG15 are near the interaction site with mUPS1863 and the sulfate ion in the mISG15-mUPS18 complex63. Therefore, E132A/D133A substitution in hISG15 may enhance hISG15-UPS18 complex formation.

The regulation of ISGylation is particularly important because of its involvement in the immune system. However, the chemicals or nutrients that facilitate ISGylation remain unclear. In this study, we report that SPD downregulates ISGylation, potentially by enhancing USP18-dependent de-ISGylation. Although it remains unclear whether SPD binds to ISG15 on its substrate, it may potentially bind to ISG15 through its substrate (Fig. 7K). Additionally, SPD interacts with USP18 and may enhance de-ISGylation. ISGylation facilitates antiviral activity5. Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 produces PLpro24,25,26,27,28, which has de-ISGylation activity, indicating the significance of ISGylation in antiviral activity. Therefore, sufficient SPD may support viral infection and propagation under specific conditions. However, SPD had the potential to enhance ISGylation under specific conditions (Figs. 6A and B), indicating its positive and negative role on ISGylation, potentially depending on USP18 expression levels.

Over 1100 proteins have been identified to be ISGylated8,9. A few of these have been individually analyzed, revealing that ISGylation activates or inhibits several significant biological pathways, such as autophagy, bacterial infection, cancer progression, cytoskeleton dynamics, DNA translesion synthesis, exosome secretion, hypoxic and ischemic responses, and viral infection65. However, it remains unclear whether ISGylation has a similar effect on the substrate because ubiquitination is known to destabilize the substrate. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze additional ISGylated substrates to obtain basic data and understand the physiological role of ISGylation.

The PLpro of SARS-CoV-2 has the potential to remove ISG15 from substrates24,25,26,27,28. Therefore, PLpro inhibitors have been used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection66,67,68. This indicates that relatively higher ISGylation may enhance defense against SARS-CoV-2; however, the primary ISGylated substrate crucial for antiviral activity remains unclear. IFNs induce ISG15 modification, but factors that enhance ISGylation have not yet been identified, except for nitrogen monoxide (NO), which enhances ISGylation by reducing ISG15 dimerization53. However, NO cannot be used to prevent infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, because of its relatively unstable nature, and high levels of NO can induce necrosis and apoptosis69. Additionally, neurons are sensitive to NO-induced excitotoxicity, which may cause neuronal death69. In contrast, curcumin partially prevented ISG15 activation by UBE1L, resulting in reduced ISGylation54. Therefore, consuming high amounts of curcumin may not be recommended when ISGylation is induced.

We examined a few chemicals that are easily ingested with minimal side effects. We identified that SPD reduced endogenous ISGylation levels. However, these data are crucial for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the downregulation of ISGylation. If ISGylation of an unidentified substrate prevents SARS-CoV-2 amplification and/or propagation directly or indirectly, then excessive intake of SPD, which may downregulate ISGylation, should be avoided.

Polyamines act as ROS scavengers, although their metabolism produces ROS, indicating a dual role in oxidative homeostasis, delaying various age-associated disorders and extending lifespan29,32,40. ISG15 covalently dimerizes through the disulfide bonds of cysteine residues53, thereby reducing the number of ISG15 monomers available for ISGylation53. Therefore, polyamine-derived ROS may indirectly induce ISG15 dimerization and reduce ISGylation. However, we did not detect SPD-induced ISG15 homodimerization (data not shown). The effect of SPD on ISGylation varied depending on the conditions. SPD downregulated endogenous ISGylation (Figs. 1 and 3D, and E), whereas the SPD biosynthesis inhibitor, DFMO, upregulated endogenous ISGylation (Figs. 2 and 3B, and C). In contrast, SPD upregulated ectopically overexpressed ISGylation in the absence of USP18 expression (Figs. 6A and B). Given that ISGylation is induced by UBE1L, UBE2L6, and Herc5 but reduced by USP18, the expression levels, SPD concentration, and oxidative homeostasis may explain these varying results.

In contrast, SPD directly interacted with ISG15 and USP18, potentially enhancing the ISG15-USP18 interaction and reducing ISGylation. Therefore, sufficient levels of SPD may prevent ISGylation-related immune responses. SPD also enhances mitochondrial function and contributes to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy34. Given that IFN is necessary for ISGylation, IFN expression levels may be a key factor in determining SPD’s function. SPD levels are regulated through oral uptake, cellular metabolism, and microbiota-derived intestinal production33, indicating the difficulty in controlling SPD concentrations. However, daily intake of SPD could contribute to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy. In contrast, high levels of SPD may not be beneficial when IFN is induced, such as during virus infections. It is important to assess the relationships among dietary habits, differences in intestinal microflora, cancer incidence, and antiviral activity to better understand the multifunctionality of SPD in the future.

Methods

Cell culture

HEK293T cells (American Type Culture Collection, ATCC), A549 cells (a gift from Dr. Keiichi Nakayama, Kyushu University, Japan), and RAW264.7 cells (a gift from Dr. Akihiko Yoshimura, Keio University, Japan) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (#09367-34, Nacalai Tesque). RAW264.7 cells were maintained in Petri dishes. MCF10A cells (a gift from Dr. Chin Ha Chung, Seoul National University, Korea) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin G, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF) (#AF-100-15-1 mg; PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ, USA), 5 µg/mL insulin (#099-06473; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), 1 ng/mL cholera toxin (#01-511; BioAcademia, Osaka, Japan), and 1 µg/mL hydrocortisone (#H0533; Tokyo Chemical Industry). All cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Reagents

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), a cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, Ponceau S, Triton X-100, and Tween-20 were purchased from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA). Can Get Signal was purchased from Toyobo (Osaka, Japan). SPM (#P2950), SPD (#P2957), and DFMO (#E0947) were purchased from the Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). SPM and SPD were dissolved in water at a concentration of 0.1–1 M and added to the cell culture medium. Glutathione sepharose 4B (#17-0756-01), PreScission protease (#27084301), protein A sepharose (#17078001), protein G sepharose (#17061802), and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (#17090601) were purchased from Cytiva (Tokyo, Japan). 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio] propanesulfonic acid (CHAPS) (#07957-22) and Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (#09408-52) were purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). LPS from Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 (#L2637) was purchased from Merck. Trypan blue solution (#15250061) was purchased from Life Technologies Japan (Tokyo, Japan).

Plasmid construction

Human UBE1L (NM_003335), human ISG15 (NM_005101), mouse ISG15 (NM_015783), mouse UBE2L6 (NM_019949), human Herc5 (NM_016323), and human USP18 (NM_017414) cDNA were amplified through PCR using KOD plus (TOYOBO, Tokyo, Japan) and subcloned into pcDNA3.1, pCGN, pFLAG-CMV2 (Merck), or pGEX6p-1 (Merck)13,15. Site-directed point mutations were generated using PCR with mutated primers. These constructs were confirmed through DNA sequencing.

Transduction

HEK293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids using PEIMAX (#24765-100; Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA) at a mass ratio of 1:5.

Knockdown

Knockdown of UBA1 was performed as previously described70. Briefly, siRNAs targeting UBA1 were transfected into MCF10A cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The previously validated target sequences for UBA1#1 and UBA1#2 were 5′-GCGTGGAGATCGCTAAGAA-3′71 and 5′-TCCAACTTCTCCGACTACA-3′72, respectively. The control sequence was 5′-TCAGTCGCGTTTGCGACTGGA-3′.

IFN or LPS stimulation and polyamine treatment

A549 and MCF10A cells were trypsinized and cultured for 1 day. The following day, cells were stimulated with 1,000 U/mL human IFN-α (#11100-1; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with or without polyamines for 1 day. Subsequently, the culture medium was changed after culturing for another day, with or without human IFN-α and/or polyamines. RAW264.7 cells were plated in cell culture dishes and stimulated with 0.1 µg/mL LPS with or without polyamines for 1 day. After 1 day of stimulation, the culture medium was changed, and the cells were cultured for another day with or without LPS and/or polyamines.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against mouse or human ISG15 were generated by immunizing rabbits with recombinant mouse or human ISG15 (Merck, Tokyo, Japan). Each anti-ISG15 antibody was purified from antisera using glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged mouse or human ISG15 and used for IB (1 µg/mL in Can Get Signal). Antibodies against the following proteins were also used: FLAG (1 µg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]; M2; Merck), FLAG (used for IP; F2555; Merck), ubiquitin (0.2 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; sc-8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), hemagglutinin (0.3 µg/mL in PBS; sc-7392; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Herc5 (0.5 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; BML-PW0920; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), UBA1 (0.2 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; sc-53555; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), UBE1L (0.2 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; sc-390097; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), UBE2L6 (0.5 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; ab109086; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), Ube2l6 (0.1 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; sc-166276; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), USP18 (1 µg/mL in Can Get Signal; 4813; Cell Signaling Technology, Tokyo, Japan), and V5 (0.2 µg/mL in PBS; sc-271944; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Cell lysis, IP, and Western blotting

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.4 mM sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4), 0.4 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium fluoride (NaF), 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail, following the manufacturer’s protocol. For examining the endogenous interaction between ISG15 and USP18, 0.5% Triton X-100 was used. Proteins were denatured using SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled, separated through SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Protran NC 0.1; 10600000; Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). For IP, the lysates were incubated with 0.5 µg of antibody for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by incubation with 10 µL of protein A/G sepharose beads (1:1 mixture of protein A sepharose and protein G sepharose) for 1 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted using SDS-PAGE sample buffer by boiling, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Subsequently, the membrane was placed in 3% skim milk in PBS at room temperature (25 °C) for 15 min and incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The membranes were washed thrice with Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% tween-20 at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:8,000-dilution in 3% skim milk in PBS; A4416; Merck) or anti-rabbit IgG (1:8,000-dilution in 3% skim milk in PBS; A6154; Merck) at room temperature for 1 h, and washed thrice with TBST for 15 min. Protein levels were measured using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Luminata Forte, Merck, or Super Signal West Pico PLUS, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the SOLO.7 S.EDGE system (Vilber, France). Images were processed using Photoshop without cropping from different parts of the same gel, different gels, or fields.

Polyamine-conjugated Sepharose pull-down assay

NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow was washed thrice with ice-cold 1 mM HCl and once with coupling buffer (0.2 M NaHCO3 and 0.5 M NaCl). SPD or SPM was dissolved in a coupling buffer at a concentration of 20 µM. NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (0.5 mL) was incubated with SPD/SPM solution (0.5 mL) for 4 h at room temperature, followed by washing with solution A (0.5 M ethanolamine-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3) and then solution B (0.1 M acetic acid-NaOH, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4.0). SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose was washed twice with solutions A and B and stored in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and 0.1% NaN3 at 4 °C. For the control experiment, NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow was washed with PBS and incubated overnight in solution A. Recombinant ISG15 (2 µg) and SPD- or SPM-conjugated sepharose (7 µL) were incubated in lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 as the detergent to pull down mouse ISG15 at 4 °C for 1 h. In contrast, a lysis buffer containing 0.25% CHAPS instead of 1% Triton X-100 was used to pull down human ISG15. A lysis buffer containing 0.2% Triton X-100 was used to pull down human USP18. Sepharose was washed thrice with each lysis buffer, denatured using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer, and boiled.

Purification of Recombinant proteins

GST-fused ISG15 was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL (Agilent Technologies International Japan, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which was cultured in 200 mL of 2×YT medium in the presence of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 3 h at 37 °C. The GST-fused USP18 was expressed for 16 h at 16 °C in the presence of IPTG (0.1 mM). Bacterial cells were washed once with PBS, resuspended in 4 mL of lysis buffer, and lysed via sonication. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation (10 min, 13,000 × g). Glutathione sepharose 4B beads (300 and 40 µL for ISG15 and USP18 purification, respectively) were added to the resulting supernatant, and the mixture was rotated at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed once with PBS and four times with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0). Recombinant ISG15 and USP18 were recovered by incubating the beads with 20 and 5 units of PreScission Protease in 0.7 and 0.2 mL wash buffer, respectively, for 16 h at 4 °C.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of three or four independent experiments. The means of different groups were compared using the Student’s t-test in Microsoft® Excel® LTSC MSO. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

Requests for further information and resources should be directed to the lead contact, Fumihiko Okumura (okumura@fwu.ac.jp), and will be fulfilled accordingly. Plasmids generated in this study will be made available upon request, but a payment and/or a completed materials transfer agreement may be required.

References

McNab, F., Mayer-Barber, K., Sher, A., Wack, A. & O’Garra, A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 87–103 (2015).

Garcia-Sastre, A. & Biron, C. A. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: a lesson in detente. Science 312, 879–882 (2006).

Kawai, T. & Akira, S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 7, 131–137 (2006).

Jimenez Fernandez, D., Hess, S. & Knobeloch, K. P. Strategies to target ISG15 and USP18 toward therapeutic applications. Front. Chem. 7, 923 (2019).

Perng, Y. C. & Lenschow, D. J. ISG15 in antiviral immunity and beyond. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 423–439 (2018).

Bogunovic, D., Boisson-Dupuis, S. & Casanova, J. L. ISG15: leading a double life as a secreted molecule. Exp. Mol. Med. 45, e18 (2013).

Farrell, P. J., Broeze, R. J. & Lengyel, P. Accumulation of an mRNA and protein in interferon-treated Ehrlich Ascites tumour cells. Nature 279, 523–525 (1979).

Zhao, X. et al. Cellular targets and lysine selectivity of the HERC5 ISG15 ligase. iScience 27, 108820 (2024).

Loeb, K. R. & Haas, A. L. The interferon-inducible 15-kDa ubiquitin homolog conjugates to intracellular proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 7806–7813 (1992).

Tsai, J. M., Nowak, R. P., Ebert, B. L. & Fischer, E. S. Targeted protein degradation: from mechanisms to clinic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 740–757 (2024).

Kok, K. et al. A gene in the chromosomal region 3p21 with greatly reduced expression in lung cancer is similar to the gene for ubiquitin-activating enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 90, 6071–6075 (1993).

Zhao, C. et al. The UbcH8 ubiquitin E2 enzyme is also the E2 enzyme for ISG15, an IFN-alpha/beta-induced ubiquitin-like protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 101, 7578–7582 (2004).

Kim, K. I., Giannakopoulos, N. V., Virgin, H. W. & Zhang, D. E. Interferon-inducible ubiquitin E2, Ubc8, is a conjugating enzyme for protein ISGylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 9592–9600 (2004).

Dastur, A., Beaudenon, S., Kelley, M., Krug, R. M. & Huibregtse, J. M. Herc5, an interferon-induced HECT E3 enzyme, is required for conjugation of ISG15 in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4334–4338 (2006).

Zou, W. & Zhang, D. E. The interferon-inducible ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase (E3) EFP also functions as an ISG15 E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3989–3994 (2006).

Okumura, F., Zou, W. & Zhang, D. E. ISG15 modification of the eIF4E cognate 4EHP enhances cap structure-binding activity of 4EHP. Genes Dev. 21, 255–260 (2007).

Ketscher, L., Basters, A., Prinz, M. & Knobeloch, K. P. mHERC6 is the essential ISG15 E3 ligase in the murine system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417, 135–140 (2012).

Durfee, L. A., Lyon, N., Seo, K. & Huibregtse, J. M. The ISG15 conjugation system broadly targets newly synthesized proteins: implications for the antiviral function of ISG15. Mol. Cell. 38, 722–732 (2010).

Honke, N., Shaabani, N., Zhang, D. E., Hardt, C. & Lang, K. S. Multiple functions of USP18. Cell. Death Dis. 7, e2444 (2016).

Liu, L. Q. et al. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease, UBP43, cloned from leukemia fusion protein AML1-ETO-expressing mice, functions in hematopoietic cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 3029–3038 (1999).

Malakhov, M. P., Malakhova, O. A., Kim, K. I., Ritchie, K. J. & Zhang, D. E. UBP43 (USP18) specifically removes ISG15 from conjugated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9976–9981 (2002).

Schwer, H. et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel human ubiquitin-specific protease, a homologue of murine UBP43 (Usp18). Genomics 65, 44–52 (2000).

Eriani, G. & Martin, F. Viral and cellular translation during SARS-CoV-2 infection. FEBS Open. Bio. 12, 1584–1601 (2022).

Freitas, B. T. et al. Characterization and noncovalent Inhibition of the deubiquitinase and deisgylase activity of SARS-CoV-2 Papain-Like protease. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 2099–2109 (2020).

Clemente, V., D’Arcy, P. & Bazzaro, M. Deubiquitinating enzymes in coronaviruses and possible therapeutic opportunities for COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 3492 (2020).

Clasman, J. R., Everett, R. K., Srinivasan, K. & Mesecar, A. D. Decoupling deisgylating and deubiquitinating activities of the MERS virus papain-like protease. Antiviral Res. 174, 104661 (2020).

Klemm, T. et al. Mechanism and Inhibition of the papain-like protease, PLpro, of SARS-CoV-2. EMBO J. 39, e106275 (2020).

Shin, D. et al. Papain-like protease regulates SARS-CoV-2 viral spread and innate immunity. Nature 587, 657–662 (2020).

Miller-Fleming, L., Olin-Sandoval, V., Campbell, K. & Ralser, M. Remaining mysteries of molecular biology: the role of polyamines in the cell. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 3389–3406 (2015).

Proietti, E., Rossini, S., Grohmann, U. & Mondanelli, G. Polyamines and kynurenines at the intersection of immune modulation. Trends Immunol. 41, 1037–1050 (2020).

Li, M. M. & MacDonald, M. R. Polyamines: Small molecules with a big role in promoting virus infection. Cell. Host Microbe. 20, 123–124 (2016).

Hofer, S. J. et al. Mechanisms of spermidine-induced autophagy and geroprotection. Nat. Aging. 2, 1112–1129 (2022).

Madeo, F., Eisenberg, T., Pietrocola, F. & Kroemer, G. Spermidine in health and disease. Science 359, eaan2788 (2018).

Al-Habsi, M. et al. Spermidine activates mitochondrial trifunctional protein and improves antitumor immunity in mice. Science 378, eabj3510 (2022).

Qu, T. et al. ISG15 targets glycosylated PD-L1 and promotes its degradation to enhance antitumor immune effects in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Transl Med. 21, 341 (2023).

Alvarez, E. et al. Unveiling the multifaceted roles of ISG15: from Immunomodulation to therapeutic frontiers. Vaccines (Basel). 12, 153 (2024).

Desai, S. D. et al. Elevated expression of ISG15 in tumor cells interferes with the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 66, 921–928 (2006).

Soda, K., Uemura, T., Sanayama, H., Igarashi, K. & Fukui, T. Polyamine-rich diet elevates blood spermine levels and inhibits pro-inflammatory status: an interventional study. Med. Sci. (Basel). 9, 22 (2021).

Atiya Ali, M., Poortvliet, E., Stromberg, R. & Yngve, A. Polyamines in foods: development of a food database. Food Nutr. Res. 55 (2011).

Murray Stewart, T., Dunston, T. T., Woster, P. M. & Casero, R. A. Jr. Polyamine catabolism and oxidative damage. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 18736–18745 (2018).

Mounce, B. C. et al. Interferon-induced spermidine-spermine acetyltransferase and polyamine depletion restrict Zika and Chikungunya viruses. Cell. Host Microbe. 20, 167–177 (2016).

Mastrodomenico, V. et al. Polyamine depletion inhibits bunyavirus infection via generation of noninfectious interfering virions. J. Virol. 93, e00530–e00519 (2019).

Firpo, M. R. & Mounce, B. C. Diverse functions of polyamines in virus infection. Biomolecules 10, 628 (2020).

Huang, M., Zhang, W., Chen, H. & Zeng, J. Targeting polyamine metabolism for control of human viral diseases. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 4335–4346 (2020).

Yang, Q. et al. Spermidine alleviates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis through inducing inhibitory macrophages. Cell. Death Differ. 23, 1850–1861 (2016).

Liu, R. et al. Spermidine endows macrophages anti-inflammatory properties by inducing mitochondrial superoxide-dependent AMPK activation, Hif-1alpha upregulation and autophagy. Free Radic Biol. Med. 161, 339–350 (2020).

Mondanelli, G. et al. A relay pathway between arginine and Tryptophan metabolism confers immunosuppressive properties on dendritic cells. Immunity 46, 233–244 (2017).

Hasko, G. et al. Spermine differentially regulates the production of interleukin-12 p40 and interleukin-10 and suppresses the release of the T helper 1 cytokine interferon-gamma. Shock 14, 144–149 (2000).

Yuan, H., Wu, S. X., Zhou, Y. F. & Peng, F. Spermidine inhibits joints inflammation and macrophage activation in mice with Collagen-Induced arthritis. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 2713–2721 (2021).

Janakiram, N. B. et al. Potentiating NK cell activity by combination of rosuvastatin and difluoromethylornithine for effective chemopreventive efficacy against colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 6, 37046 (2016).

Chamaillard, L., Quemener, V., Havouis, R. & Moulinoux, J. P. Polyamine deprivation stimulates natural killer cell activity in cancerous mice. Anticancer Res. 13, 1027–1033 (1993).

Zhang, H. & Simon, A. K. Polyamines reverse immune senescence via the translational control of autophagy. Autophagy 16, 181–182 (2020).

Okumura, F., Lenschow, D. J. & Zhang, D. E. Nitrosylation of ISG15 prevents the disulfide bond-mediated dimerization of ISG15 and contributes to effective ISGylation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24484–24488 (2008).

Oki, N. et al. Curcumin partly prevents ISG15 activation via ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like protein and decreases ISGylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 625, 94–101 (2022).

Huang, X. & Dixit, V. M. Drugging the undruggables: exploring the ubiquitin system for drug development. Cell. Res. 26, 484–498 (2016).

Liu, M., Li, X. L. & Hassel, B. A. Proteasomes modulate conjugation to the ubiquitin-like protein, ISG15. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1594–1602 (2003).

Wong, J. J., Pung, Y. F., Sze, N. S. & Chin, K. C. HERC5 is an IFN-induced HECT-type E3 protein ligase that mediates type I IFN-induced ISGylation of protein targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 103, 10735–10740 (2006).

Li, X. L. et al. RNase-L-dependent destabilization of interferon-induced mRNAs. A role for the 2-5A system in Attenuation of the interferon response. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 8880–8888 (2000).

Okumura, F. et al. Activation of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) by interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) modification down-regulates protein translation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 2839–2847 (2013).

Hunt, L. C. et al. An adaptive stress response that confers cellular resilience to decreased ubiquitination. Nat. Commun. 14, 7348 (2023).

Dao, C. T. & Zhang, D. E. ISG15: a ubiquitin-like enigma. Front. Biosci. 10, 2701–2722 (2005).

Kuttan, G., Kumar, K. B., Guruvayoorappan, C. & Kuttan, R. Antitumor, anti-invasion, and antimetastatic effects of Curcumin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 595, 173–184 (2007).

Basters, A. et al. Structural basis of the specificity of USP18 toward ISG15. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 270–278 (2017).

Bonacci, T., Bolhuis, D. L., Brown, N. G. & Emanuele, M. J. Mechanisms of USP18 deISGylation revealed by comparative analysis with its human paralog USP41. bioRxiv (2024).

Villarroya-Beltri, C., Guerra, S. & Sanchez-Madrid, F. ISGylation - a key to lock the cell gates for preventing the spread of threats. J. Cell. Sci. 130, 2961–2969 (2017).

Garnsey, M. R. et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PL(pro)) inhibitors with efficacy in a murine infection model. Sci. Adv. 10, eado4288 (2024).

Li, M. et al. In-cell bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based assay uncovers ceritinib and CA-074 as SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 39, 2387417 (2024).

Velma, G. R. et al. Non-covalent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Papain-Like protease (PLpro): in vitro and in vivo antiviral activity. J. Med. Chem. 67, 13681–13702 (2024).

Brown, G. C. Nitric oxide and neuronal death. Nitric Oxide. 23, 153–165 (2010).

Uematsu, K. et al. ASB7 regulates spindle dynamics and genome integrity by targeting DDA3 for proteasomal degradation. J. Cell. Biol. 215, 95–106 (2016).

Moudry, P. et al. Ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBA1 is required for cellular response to DNA damage. Cell. Cycle. 11, 1573–1582 (2012).

Kumbhar, R. et al. Recruitment of ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBA1 to DNA by poly(ADP-ribose) promotes ATR signalling. Life Sci. Alliance. 1, e201800096 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Keiichi Nakayama (Kyushu University, Japan) for providing A549 cells, Dr. Yoshimura Akihiko (Keio University, Japan) for providing RAW264.7 cells, and Dr. Chin Ha Chung (Seoul National University, Korea) for providing MCF10A cells. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E., R.A., T.O., and F.O.; Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, and Assessment, H.E., R.A., T.O., and F.O.; Data Curation, H.E., R.A., T.O., and F.O.; Writing-Original Draft, F.O.; Writing-Review and Editing, H.E., T.O., and F.O.; Supervision, F.O.; Project Administration, F.O.; and Funding Acquisition, F.O.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Etori, H., Asoshina, R., Obita, T. et al. Spermidine reduces ISGylation and enhances ISG15–USP18 interaction. Sci Rep 15, 17913 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01425-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01425-0